6

PROTECTING OURSELVES

The Role of Head Trauma, Exercise, and Diet

Muhammad is battling a relentless, remorseless, insidious thief. Parkinson’s recognizes no title, respects no achievements, nor bows to any amount of talent, courage, or character. Parkinson’s does not discriminate. There is no question that Parkinson’s is the fight of Muhammad’s life.

—Lonnie Ali, in testimony to Congress in 20021

FOR MOST OF HIS LIFE, MUHAMMAD ALI RAISED OUR CONSCIOUSNESS. He did so about the Vietnam War, racism, identity, religious freedom, and, finally, the health risks of head trauma.

On December 11, 1981, Ali took on Trevor Berbick in his sixty-first and final professional fight. Three years later, he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s. For twenty-seven years, Muhammad Ali fought boxers. For the next thirty-two, he would be in the ring with Parkinson’s disease. At the time of his diagnosis, little was known about the link between head trauma and developing the disease.2 Since then, multiple studies have found that repetitive blows to the head increase the risk.3

In 2006, researchers discovered that even a single head injury resulting in loss of consciousness or amnesia tripled the risk of Parkinson’s.4 Repeated head trauma raised the risk even further.5 Traumatic brain injury increases not only the chances of developing the disease but also the rate of progression of parkinsonian features. It also leads to the accumulation of Lewy bodies, those clumps of misfolded proteins found in the brains of people with Parkinson’s.6 And just as the combination of particular gene mutations and chemical exposure can up our odds, so too can the risk of traumatic brain injury be amplified by environmental pressures. Head trauma plus exposure to the pesticide paraquat almost triples a person’s risk of the disease.7

Football players, especially professional ones, are, of course, vulnerable. They are more likely to develop neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which, resulting from repeated brain trauma, can lead to dementia.8 The link between playing professional football and Parkinson’s disease, however, is less clear. A 2012 study found that National Football League (NFL) players face an almost three times greater risk of death due to conditions like ALS—Lou Gehrig’s disease—and Alzheimer’s but not Parkinson’s.9

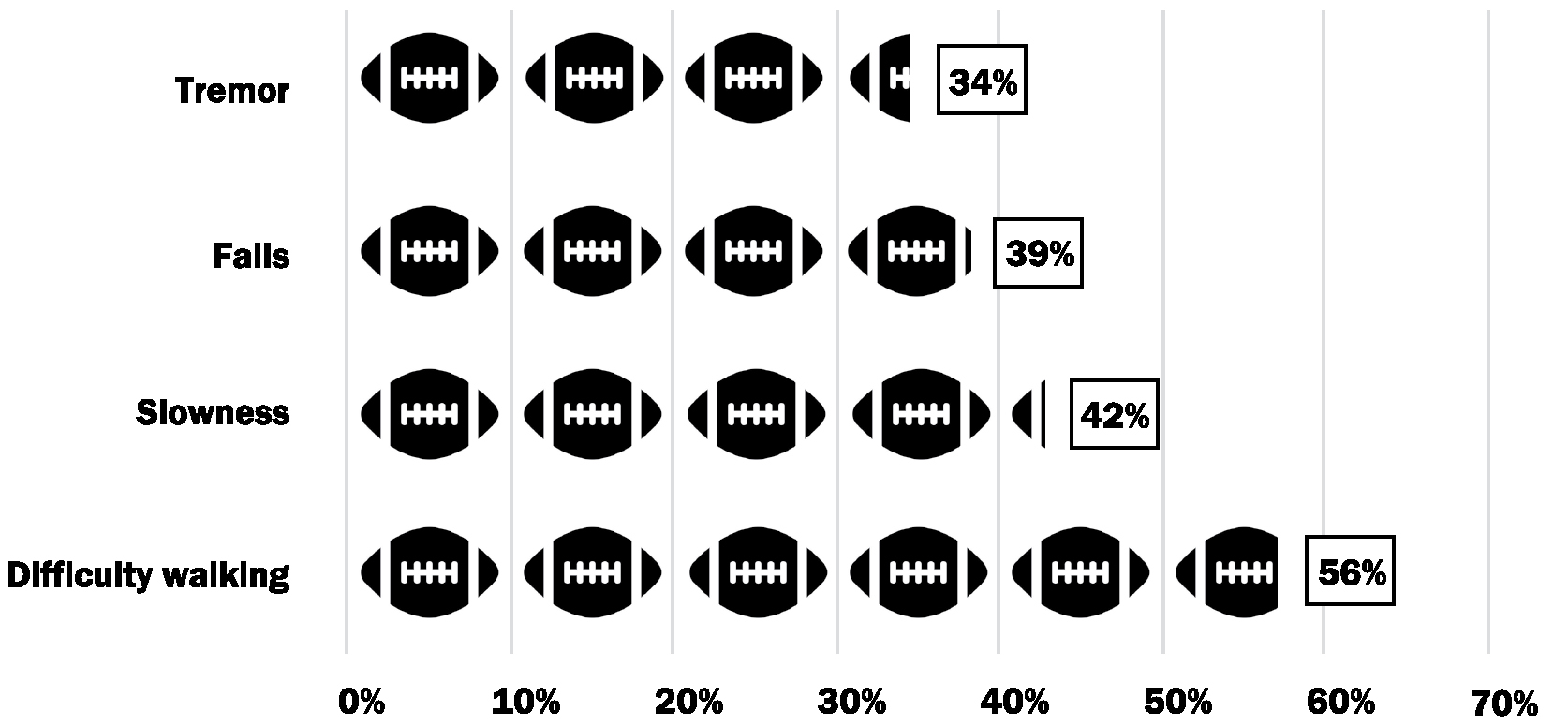

But a 2017 study of football players, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, found a connection. The risk of CTE increased with the duration and intensity of a person’s football experience and was present in the brains of almost every former NFL player in the study—110 out of 111. It also showed up in people who had played high school football, but in fewer of them—three out of fourteen.10 And among the former professional players with CTE, two-thirds had parkinsonian features, including slowness, a tendency to fall, and tremors (Figure 1). Six of the 111 had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s.11

Fueled by these concerns, some NFL players are making big life changes. Chris Borland, a rookie linebacker who led the San Francisco 49ers in tackles in 2014, is one example. At the age of twenty-four, he walked away from the remainder of a nearly $3 million contract and the life of a professional football player.12 In the Huffington Post, the former University of Wisconsin all-American wrote, “Had I stopped playing football following high school, I wouldn’t understand why a 24-year-old would quit the NFL just one year into his professional career. If I hadn’t made hundreds upon hundreds of tackles during college and my time in the pros, I might be susceptible to the thinking [that] a player can do so safely. My post–high school experiences gave the mounting and damning evidence that football causes brain damage far more gravity. The tragic stories I’d heard murmurings about since my high school days weren’t outliers like I’d been led to believe.”14

FIGURE 1. Proportion of NFL players experiencing parkinsonian symptoms in a 2017 study.13

He was right. In 2009, after decades of denial, an NFL spokesman told the New York Times, “It’s quite obvious from the medical research that’s been done that concussions can lead to long-term problems.”15 In 2014, the NFL released documents in a court proceeding indicating that the organization expects nearly a third of its retired players to develop long-term cognitive problems at “notably younger ages” than the general population.16 These admissions helped form the basis of a legal settlement in which the NFL agreed to provide $765 million in medical aid to more than 18,000 former NFL players.17

A year and a half after the settlement went into effect, claims for neurodegenerative disorders exceeded all expectations. According to a 2018 Los Angeles Times article, 113 retired players have already filed claims related to Parkinson’s; 81 have been either paid or approved.18 The number of claims far exceeds the projection that only fourteen claims for the disease would be paid over the sixty-five-year duration of the settlement.19 In the first eighteen months, the number of Parkinson’s claims was five times greater than the amount predicted for sixty-five years.

Over a career that began in 1956 and spanned fifteen seasons, Forrest Gregg played in 188 consecutive NFL games during his Hall of Fame career. He is just one of many former professional players who have been diagnosed with Parkinson’s.20 Gregg was a nine-time Pro Bowl offensive lineman for the Green Bay Packers and Dallas Cowboys who went on to coach the Cincinnati Bengals to their first Super Bowl appearance in 1982.

During his playing career, Gregg suffered countless concussions. In his sixties, Gregg began acting out his dreams at night, an early sign of Parkinson’s. He dreamed that he was blocking for quarterback legend Bart Starr. Gregg ended up knocking his wife out of bed. In his seventies, Gregg developed a soft voice, tremors in his hands, and a stooped posture that led to his diagnosis. If he had known the risks, Gregg said that he would have still played football, though he may have shortened his career.21 In 2019 Forrest Gregg died from complications of Parkinson’s disease.22

Concussions are not just an issue for professional football players. According to one study, among youth football players aged eight to twelve, the rate of concussions is comparable to that reported for high school and college athletes.23 Some studies report lower rates and some higher, especially for college athletes.24

Concussions in sports are generally underreported. For example, among 1,500 high school varsity football players in Wisconsin, 30% reported a previous history of at least one concussion, and 15% reported a concussion in that season. According to a confidential survey, less than half of the players reported their concussions that season to a coach, teammate, trainer, or parent.25 Pressure from coaches, teammates, parents, or fans contribute to the silence. More than 25% of female and college athletes continue playing after a suspected concussion because of such pressure.26

Football, of course, is not the only sport with a high concussion rate. Boys’ ice hockey and lacrosse and girls’ soccer and lacrosse also have high rates.27 However, football is the clear leader. In a national sample of US high school athletes for twenty sports, football accounted for 47% of all concussions.28 Some efforts have been made to limit contact, enforce rules, and educate players.29 These are likely not enough.

Military veterans also pay the price of traumatic brain injury. In a 2018 study, researchers examined the records of more than 300,000 individuals from a Veterans Health Administration database.30 Nearly 1,500 individuals were diagnosed with Parkinson’s after having a traumatic brain injury, often due to explosions. Mild traumatic brain injury in veterans increased the risk of developing Parkinson’s by more than 50%.31 More severe injury was associated with an even higher risk.

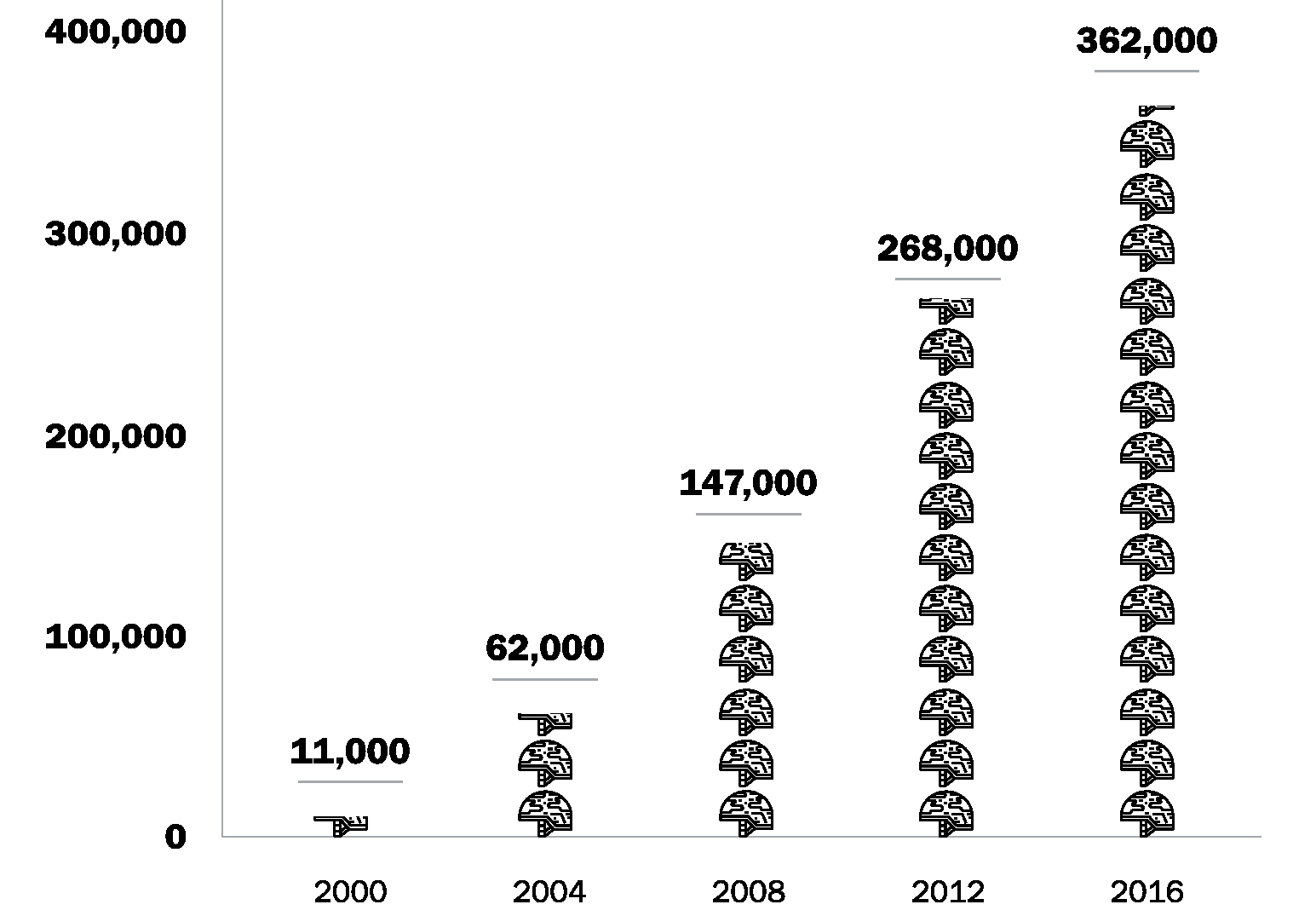

The burden of Parkinson’s disease linked to traumatic brain injury is poised to grow. According to the US Department of Defense, nearly 400,000 service members have been diagnosed with a traumatic brain injury since 2000 (Figure 2).32 Another 8 million veterans have likely experienced such an injury.34 For those with moderate or severe traumatic brain injury, one in fifty will likely develop Parkinson’s within twelve years.35 Traumatic brain injury adds to the risk of Parkinson’s among veterans, many of whom have already been exposed to the pesticide Agent Orange and chemicals like TCE.

FIGURE 2. Cumulative number of US service members diagnosed with traumatic brain injury, 2000–2016.33

MOVE YOUR BODY

Published in 1899, the two-volume Manual of Diseases of the Nervous System, written by British neurologist Dr. William Gowers, used to be referred to as the “Bible of Neurology.”36 In it, Gowers recommended that for individuals with Parkinson’s disease, “life should be quiet and regular, freed, as far as may be, from care and work.”37 Sir William Gowers never met Jimmy Choi.

Since 2012, nine years after his diagnosis with Parkinson’s at the age of twenty-seven, Choi has completed one hundred half marathons, fifteen full marathons, one ultramarathon, six Gran Fondo bicycle rides, multiple Spartan Races, and countless 5K and 10K runs. When he was first diagnosed, Choi’s life was quiet. He went into denial, hid his diagnosis even from his wife, and did nothing. By the time he was thirty-four, he weighed 240 pounds and walked with a cane. One day while carrying his young son, the two fell down a flight of stairs. Neither was hurt, but the accident motivated Choi to regain his health.38

After reading an article about someone with Parkinson’s competing in a marathon, Choi took up running. He completed a 5K, then a 10K and a 15K, and, in 2012, his first marathon.

Several years ago, while watching the television show American Ninja Warrior, Choi’s ten-year-old daughter told her father he should apply. Choi did, and in July 2017, he became the first person with Parkinson’s to compete. Choi said participating was the “most terrifying thing [he has] done.” Although he fell on the course’s balance obstacle, his performance was stirring to watch. The show’s co-host, Akbar Gbajabiamila, whose father has Parkinson’s, was visibly moved (Figure 3). A year later, Choi returned to American Ninja Warrior. Despite a noticeable tremor, he competed until he was bested by the third of ten obstacles. The crowd gave him a standing ovation.39

Choi’s exercises have a purpose. He runs to build endurance to prevent fatigue from Parkinson’s. He does burpees so he can learn how to fall safely and get back up again. He only wishes that he had embraced exercise earlier.

Choi is not sentimental about his disease. He says, “Parkinson’s sucks.” But to people who suggest that he could run even faster without it, Choi replies, “I don’t think that I would be running a marathon if I didn’t have Parkinson’s.”40

He is not the only one with Parkinson’s who has found exercise to be a boon. Cathy Frazier, a graphic design firm owner who was diagnosed in 1998 at the age of forty-three, has discovered the benefits of bicycling.41 She did so with her friend, Dr. Jay Alberts, who happens to be a neuroscientist. Alberts, an avid cyclist, thought it would be fun to ride a tandem bicycle with Frazier 460 miles across the entire state of Iowa to raise awareness of her disease. During the ride, Alberts set a quick pace. “I was driving her to pedal faster than she would on her own.”42

During their weeklong trip, both Frazier and Alberts noticed that her symptoms improved. Frazier said, “It doesn’t feel like I have Parkinson’s when I’m on the bike.” Alberts saw that her tremor subsided and her handwriting improved. Given the changes, Frazier continues to cycle, sometimes on a tandem bicycle, and her writing remains smooth and clear.43 The pair even co-founded Pedaling for Parkinson’s, an organization dedicated to understanding how physical activity affects the motor symptoms of the disease.44

Alberts began to investigate what he termed “forced exercise”—exercising at rates higher than people can achieve by themselves.45 In a small ten-person study, Alberts and his colleagues looked at individuals with Parkinson’s who rode a tandem bicycle with a trainer pushing their speed, as he had done with Frazier. The scientists found that both forced exercise and traditional bicycling improved aerobic fitness. However, only forced exercise improved motor function in the study’s participants.46

Alberts also looked into studies done on animals. In one study, mice with Parkinson’s experienced a similar benefit from forced exercise. After the mice were put on a treadmill at a faster speed than their “preferred running velocity,” their motor function improved, and growth factors for nerve cells increased.47 These growth factors help nerve cells develop and survive. They may also increase the release of dopamine and improve communication between nerve cells.48

Alberts has continued his research. In a National Institutes of Health–funded, eight-week, one-hundred-person study, he found that people with Parkinson’s who biked at high speed—between eighty and ninety revolutions per minute—appeared to have the greatest benefit from exercise. Next up is a one-year study that will follow three hundred people who are pushed beyond their usual exercise rates.

Alberts’s positive results are supported by numerous randomized controlled trials that have demonstrated the value of exercise for people with Parkinson’s—even at a pace they could achieve on their own. A review of fourteen randomized controlled trials of stretching, strength training, walking, and other exercises found that all improved physical function, quality of life, balance, and gait speed for people with the disease.49

Given the clear benefits of exercise for those with Parkinson’s, a new question arises. Can exercise help prevent Parkinson’s? Two studies published in 2018 sought to answer that question. In one, researchers examined over 7,000 veterans. They found that compared to the least physically fit, those who were in the best shape were 76% less likely to develop Parkinson’s twelve years later. Their findings and others led the researchers to conclude, “[These] observations provide strong support for recommending physical activity to diminish [the] risk of Parkinson’s disease.”50

In the second study, researchers at Zhejiang University in China reviewed eight previous studies, involving over 500,000 participants, to determine whether physical activity lowered the chances of developing Parkinson’s a decade or more later. They found that exercise was associated with a 21% decreased risk. Exercise that was moderate to vigorous and done consistently (e.g., 7 to 8 hours of walking or 3.5 to 4 hours of lap swimming each week) pushed that number even higher—to a 29% decreased risk of developing the disease.51 An additional hour per week of vigorous exercise (e.g., jumping rope) or two hours of moderate exercise (e.g., bicycling) decreased the risk of Parkinson’s by another 9%. Although promising, the protective effects of exercise are far from absolute. But science is showing that in addition to helping us feel better and live longer, exercise likely reduces our risk of Parkinson’s.52 And the more you do it, the better.53

EAT GOOD FOOD

The Mediterranean diet already has an excellent reputation. It reduces the risk of developing heart disease, memory loss, and cancer.54 It also helps us live longer.55 The diet centers on vegetables, legumes (e.g., peas, beans, lentils), fruits, cereals, and unsaturated fatty acids, especially olive oil. It emphasizes fish over dairy products, meat, and poultry, and it includes wine.56 Dr. Alberto Ascherio, an Italian physician and epidemiologist at Harvard Medical School, and his colleagues wanted to know whether the diet’s wonders extended to Parkinson’s.

To find out, they looked at what 130,000 health professionals ate. The researchers characterized their diets as either “prudent” (high in fruit, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, and fish) or “Western” (high in red meat, processed food, refined grains, French fries, sweets, and high-fat dairy products). After sixteen years, there were 22% fewer cases of Parkinson’s among the “prudent,” or Mediterranean, diet group compared to those who ate typical American fare.57 Subsequent studies have supported these findings.58

How exactly the Mediterranean diet may protect us is largely unknown.59 One possibility is that antioxidants, which are vitamins and other substances that are abundant in the diet, may reduce the clumping of alpha-synuclein into Lewy bodies inside nerve cells.60 Antioxidants can also prevent cellular damage, including to our energy-producing mitochondria, which are harmed by Parkinson’s.61 However, additional research is required to understand how diet might prevent the disease.

HELP YOURSELF TO ANOTHER CUP

Get brewing! Caffeine may be able to delay or prevent the onset of Parkinson’s. Research has repeatedly shown that caffeine consumption is associated with a decreased risk of the disease.62 And the more the better: a study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that the incidence of the disease declined with increased amounts of coffee intake.63 The effect is likely tied to caffeine rather than to coffee beans. Caffeine from other sources appears to offer a protective effect too, while decaffeinated coffee offers none.64

Ascherio and his colleagues, who studied the Mediterranean diet in those 130,000 health professionals, also looked at their caffeine consumption. After ten years, men who drank the most caffeine were 58% less likely to develop Parkinson’s than those who consumed the least. Among women, moderate caffeine drinkers (one to three cups of coffee per day) had the lowest risk of developing the disease.65

Caffeine’s actions in the brain may protect dopamine-producing nerve cells from the damage Parkinson’s does to them.66 When animals with Parkinson’s symptoms are given drugs similar to caffeine, their motor function improves. In human studies, however, researchers have not replicated those benefits. This could be because by the time people are diagnosed with Parkinson’s, too many nerve cells may already be lost—the caffeine prescription may come too late.67 As suggested by Ascherio and others, prudent caffeine intake (one to four cups) early in life could protect nerve cells and reduce the risk of ever developing Parkinson’s.68 However, caffeine has its own costs. It can cause anxiety, headaches, and other side effects.69 These effects must be weighed against its potential benefits for Parkinson’s.

Taken together, all of us can lower our risk of Parkinson’s by protecting our heads, exercising, eating a Mediterranean diet, and consuming caffeine.