INTRODUCTION

Every civilization has its own kind of pestilence and can control it only by reforming itself.

—René Dubos, Mirage of Health, 19591

ON A BRILLIANT, BLUE-SKY DAY IN JUNE 2018, THE UNIVERSITY of Rochester hosted its annual Men’s Health Day at the Locust Hill Country Club in upstate New York. Over three hundred men, most in their fifties, sixties, and seventies, came to hear the latest on enlarged prostates, colon cancer, and heart disease. I came to speak about Parkinson’s disease.

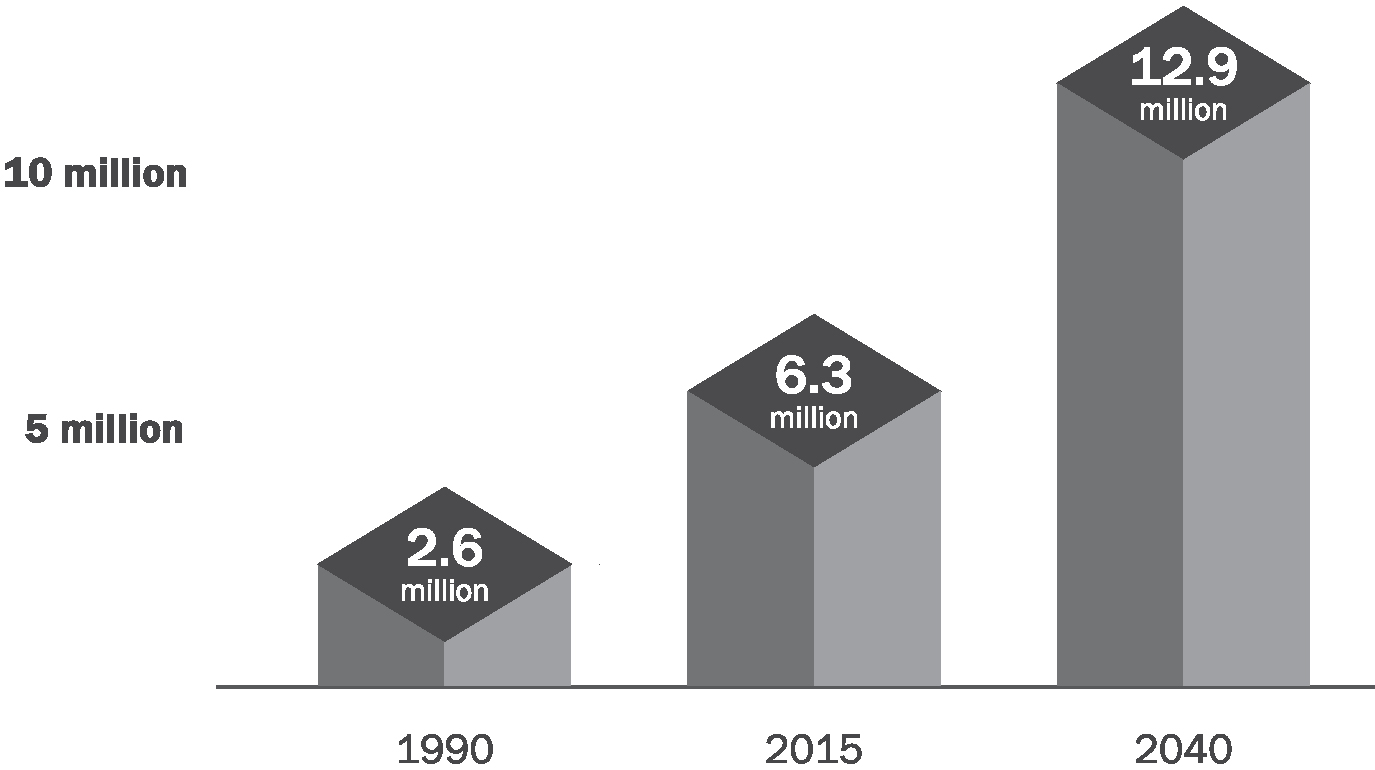

Months earlier I had written a paper titled “The Parkinson Pandemic” with my friend and colleague—and now coauthor—Bas Bloem.2 In it, we explained that neurological disorders are the world’s leading cause of disability. And the fastest growing of these conditions is not Alzheimer’s but Parkinson’s disease. From 1990 to 2015, the number of people with Parkinson’s more than doubled from 2.6 million to 6.3 million.3 By 2040, the number will double again to at least 12.9 million, a stunning rise (Figure 1).4

This is what I know. This is what I study. But as I stood there in front of the packed room at Men’s Health Day, I was not prepared for what I was about to see. I opened my talk by asking how many people in the audience had a friend or family member with Parkinson’s. Before I could finish asking the question, over two hundred hands had flown up—almost the entire room. Everyone looked around. A silence settled on us as we took in the sight. It didn’t matter that I was an expert or that I had helped develop the statistics. Data always feel remote, but here it was in front of me, the evidence of the pandemic.

FIGURE 1. Estimated and projected number of people with Parkinson’s disease globally, 1990–2040.5

Parkinson’s disease is characterized by tremors, slowness in movement, stiffness, and difficulties with balance and walking. It can also cause a wide range of symptoms that are not visible—loss of smell, constipation, sleep disorders, and depression. Most people with Parkinson’s are diagnosed in their fifties or later. But it is not just a disease of the elderly. Up to 10% of those with the condition develop the disease in their forties or younger.

Parkinson’s stems from a loss of nerve cells in a particular region of the brain that produces dopamine, the brain chemical that helps control movements such as walking. The disease has multiple causes including environmental hazards—air pollution, some industrial solvents, and particular pesticides. In addition, certain genetic mutations, head trauma, and the lack of regular exercise all increase risk.6

The scale of the disease can feel overwhelming and the challenge daunting. But we can stop Parkinson’s in some cases, and we may already know how.

In the meantime, while there is no cure for Parkinson’s yet, many aspects of it are treatable. Just as exercise can reduce our risk of developing the disease, it can also help alleviate its symptoms.7 Medications aimed at replacing the dopamine that is lost in the brain are also beneficial. However, complications can develop with high doses or long-term use of some drugs. In certain cases, brain surgery can help treat these side effects.8

Although Parkinson’s is a progressive disorder—it becomes worse over time—most people can still live long and productive lives. Especially for the first five to ten years following diagnosis, individuals can function at high levels, working, traveling, and enjoying life.

Of course, the disease still takes a profound toll on individuals and their families. Up to 40% of people with Parkinson’s will eventually require nursing home care, and the caregiving burden is immense.9 Life expectancy is reduced modestly, and many die from falls or pneumonia.10

THE SEMINAL DESCRIPTION OF PARKINSON’S DISEASE CAME IN 1817, at the height of the Industrial Revolution in London.11 Dr. James Parkinson observed six individuals who walked with an unusual gait and had “shaking limbs.” Parkinson’s disease, as it became known, was almost certainly rare then.

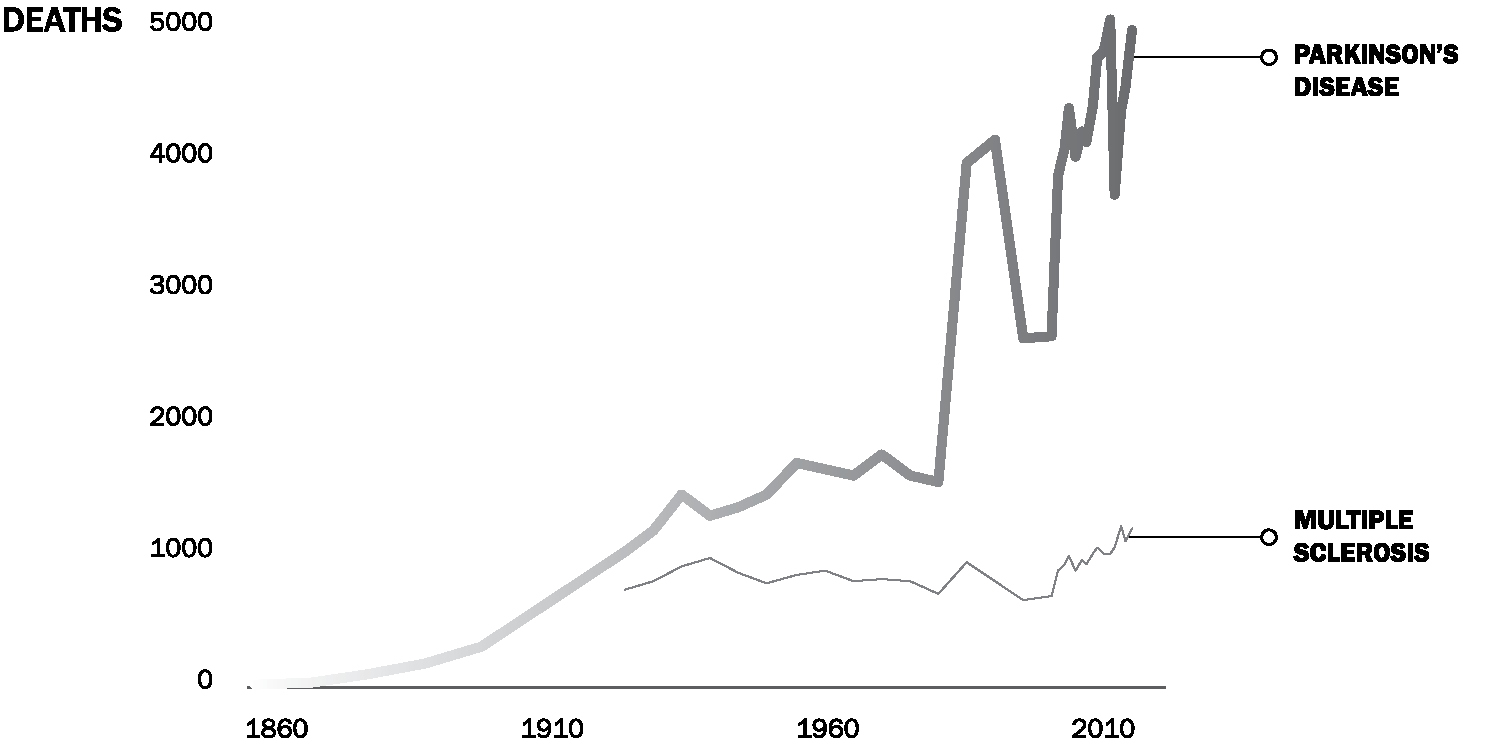

Neither our increased awareness of the disease nor our lengthening lifespans can fully account for the upsurge in diagnoses that we now face. Our knowledge of another neurological disorder, multiple sclerosis, has increased too, and we have improved diagnostic tools for it. Rates for multiple sclerosis have indeed gone up, but that increase is nothing like the exponential rise of Parkinson’s (Figure 2). As for aging, more people are, of course, living longer. For example, from 1900 to 2014, the number of individuals over age sixty-five in the United Kingdom increased about sixfold. However, over that same period, the number of deaths due to Parkinson’s disease increased almost three times faster.

FIGURE 2. Number of deaths caused by Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis in England, 1860–2014.12 Changes in coding in the 1980s likely contributed to the fluctuations in deaths recorded during this period.

How did we get here? While industrialization has raised incomes and life expectancies around the world, its products and by-products are also likely increasing the rates of Parkinson’s.13 Air pollution began to worsen in England in the eighteenth century, metal production and its harmful fumes increased in the 1800s, the use of industrial chemicals rose in the 1920s, and synthetic pesticides—many of which are nerve toxins—were introduced in the 1940s.14 All are linked to Parkinson’s—people with the most exposure have higher rates of the disease than the general population.

The evidence for this connection is overwhelming. Countries that have experienced the least industrialization have the lowest rates of the disease, while those that are undergoing the most rapid transformation, such as China, have the highest rates of increase.15 Specific metals, pesticides, and other chemicals have all been tied to Parkinson’s in numerous human studies.16 When animals are exposed to many of these substances in lab experiments, they develop the typical characteristics of the disease, including difficulty walking and tremors.17

Despite the vast evidence, we are doing little to manage these threats. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) had at one time proposed banning one of the chemicals that is tied to Parkinson’s, a solvent called trichloroethylene. But after lobbying by the chemical industry, the EPA decided in 2017 to postpone the ban indefinitely.18 The uses of trichloroethylene have been so numerous and widespread—in washing away grease, cleaning silicon wafers, removing spots in dry cleaning, and even, until the 1970s, decaffeinating coffee—that almost all of us have been exposed to it at some point in our lives.19 Some of these uses continue today. Almost half of Superfund sites—land so polluted that the EPA or the responsible parties have to clean it up—which are found in nearly every state, are contaminated with trichloroethylene.20 Thousands of other sites are polluted across the country, including one, as I discovered in the process of writing this book, fifteen minutes from my home.21

As a result, up to 30% of the US drinking water supply has been contaminated with trichloroethylene.22 Because it readily evaporates from groundwater and soil, the solvent, like radon, can enter homes or offices through the air, undetected.23 Parkinson’s is not even the most concerning safety risk. According to the EPA, trichloroethylene also causes cancer.24

But trichloroethylene is only one dangerous chemical that we have failed to protect ourselves against. Paraquat is a pesticide that is so toxic that thirty-two countries, including China, have banned it.25 Exposure to the chemical increases the risk of Parkinson’s by 150%.26 Yet the EPA has done little. And as the agency charged with protecting our environment sits, paraquat’s use on US agricultural fields has doubled over the last decade.27

The nerve toxin chlorpyrifos is the most widely used insecticide in the country, drenching golf courses and dozens of crops, including almonds, cotton, grapes, oranges, and Washington State apples. It has been linked not only to Parkinson’s but also to problems with brain development in children. Again, the EPA has shelved a ban. When a federal court stepped in to take action against the chemical, the Trump administration appealed.28 And in July 2019 in response to a court ordering a final ruling, the EPA decided that it would allow continued use of chlorpyrifos.29

All of the evidence indicates that the full effect of the Parkinson’s pandemic is not inevitable but, to a large extent, preventable. However, we cannot remain silent.

We have been here before. We have faced down other difficult illnesses that have threatened us. Three of them—polio, HIV, and breast cancer—share similarities with Parkinson’s and offer valuable lessons for how we can take it on. Polio is a disabling neurological condition. HIV affected large numbers of individuals globally in a very short period. Breast cancer likely has both environmental and genetic causes.30 At some point, society ignored all three until the people who knew the diseases intimately—and understood their toll firsthand—stepped forward. Their activism changed the courses of these diseases and has improved and saved the lives of millions.

That is why we are writing this book. Yes, we are sounding the alarm that this pandemic is upon us. But we also know that if we respond now to the challenge it presents, we can save many people from suffering. Individually and collectively, we can take some very practical actions to stop the damage.

In Ending Parkinson’s Disease, we will discuss what new policies, protections, and resources can slow the disease. The Netherlands, for example, banned trichloroethylene, paraquat, and other pesticides linked to Parkinson’s years ago—and it worked. Rates of the disease decreased.31 This outcome shows how stemming the tide of Parkinson’s is within our reach.

We will also examine how we can offer better support and care to the millions affected by Parkinson’s today. We will see what new therapies are on the horizon and how close we are to introducing novel treatments that may slow or stop the progression of Parkinson’s. Some of these will arrive in time to help people who already have the disease. Others may even help to prevent Parkinson’s altogether.

At the end of the book, we outline what all of us can do to lower our risk, increase resources to address the condition, extend expert care to all those in need, and slow the advance of Parkinson’s.

Along the way, we will highlight the experiences of courageous individuals with the disease, tireless caregivers, and fearless advocates. We will hear their stories, learn from their experiences, and take inspiration from their actions.

The four of us—one neuroscientist and three neurologists who specialize in Parkinson’s—have devoted most of our professional lives to this disease. Twenty years ago, Dr. Todd Sherer conducted groundbreaking research linking pesticides to Parkinson’s disease. He now leads The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, the largest private funder of Parkinson’s research in the world.32 Dr. Michael Okun, who first characterized Parkinson’s as a pandemic, has pioneered new surgical treatments for people with the disease and written multiple books and articles on the topic.33 Professor Bas Bloem is a leading authority on gait disturbances and falls in Parkinson’s and co-created the world’s largest care program for people with the disease.34 And with my colleagues, I have used technology to expand access to care and develop new methods for measuring the disease.35 All of us are working to advance better treatments for the condition.

While we are hopeful about making our patients’ lives better, our true passion is preventing people from ever having to face Parkinson’s. We are frustrated when we see women and men in our clinics who have suffered head trauma or been exposed to pesticides on a farm, solvents at work, contaminated groundwater in their neighborhoods, or polluted air in their homes. All of these risks for Parkinson’s can be mitigated. We humans have helped create this pestilence. And we can now work to end it.