CHAPTER FIVE

The Fourfold Gospel Book

What Is a Gospel?

In terms of both influence and literary space, the canonical Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) are the primary documents of the New Testament. Together the four Gospels make up almost 45 percent of the New Testament, and they have long stood at the head of the New Testament’s canon of sacred literature. The Gospels have been primary in influence because Christianity is above all else a call to follow a particular person, Jesus of Nazareth, who claimed to be the promised Jewish Messiah and the true king of the whole world. Christianity has always understood itself as a call to believe in, give allegiance to, and worship a certain person, not just an invisible god or an intangible and impersonal set of beliefs. Therefore, the Gospel stories about him have played a central role.

This radical belief that Jesus is the incarnation of God means that his actions, teachings, and example are all essential to what Christianity is and what Christians most need to know. Doctrinal teachings about the theological significance of Jesus’s death and resurrection are central to Christianity as well, but to be a disciple/follower requires more than theological head knowledge about what Jesus did. Christians need to know Jesus the person. Therefore, early Christians wrote what was needed: biographies that record events and teachings about Jesus in story form and that show, not just tell, who this Jesus is. This is what the canonical Gospels are—theological biographies.

Ancient Christians are not the only ones who have cared about biographies. People throughout all ages, including today, have been fascinated by other people’s stories, especially famous and influential figures—athletes, actors, politicians, innovators, religious leaders, artists, and great intellectuals. In the Greek and Roman culture of the first century AD, when Christianity was born and growing into all the world, a very important type of Greek (and Latin) literature was the bios, from which we get our word “biography”—the writing (graphē) about someone’s life (bios). The genre of the bios was the central means by which important historical figures were represented and remembered, with their ideas and actions recorded so that they could be spread beyond the person’s place and time, often with an explicit invitation to imitation. This is what the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are.

Richard Burridge, one of the leading scholars of ancient biographies, shows how similar the Gospels are to other contemporary bios literature.1 Typical of this genre, the Gospels focus on one person, the subject of a biography, revealing Jesus’s teachings and actions. All other characters and events in a biography are directly related to the focal person that the bios is about. Hearers of the Greek-language Gospels in the ancient world would have been familiar with this genre and understand its purpose. This is a good example of Christianity contextualizing itself into the surrounding culture, relating the truth of Jesus in a language, genre, and way of thinking that was familiar to the Greco-Roman world.

At the same time, this contextualization of the message about the Jewish Jesus into a Greek bios also created its own version of the ancient biography. We may notice that the four Gospels are titled not “The Bios/Life of Jesus according to . . . ” but rather “The Gospel according to . . .” This word “gospel” (Greek, euangelion) was how Paul described his own preaching about Jesus (1 Cor. 15:1–2; Gal. 1:6–9) and is first applied to the narratives about Jesus in Mark 1:1: “The beginning of the good news [euangelion] about Jesus the Christ, the Son of God” (AT). Then, early on in the church, the four recognized biographies that were compiled by Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John all came to be titled with the superscription “The Gospel according to . . .”

This shift from “life” to “gospel” is very important in tying the story of Jesus into the broader story of Israel, of God’s work in the world from the beginning of creation up until Jesus. Specifically, the language of “gospel” comes from the influential writings of the prophet Isaiah. In the Greek translation of Isaiah the verb form of the noun “gospel” (euangelion) is used at crucial points to describe the great theme of the book: God is going to return soon to establish his good reign on the earth, forgiving people’s sins, vindicating and providing for his faithful people, instituting true peace and flourishing throughout the world (Isa. 40:1–11; 52:7–53:12). This can be described biblically as “the kingdom of God,” and it is a forward-looking hope and promise for the future. Thus, our Gospels are Greek biographies, but biographies that set Jesus’s teachings and actions into a broader, comprehensive story of the whole world, both human and divine, a story that points forward to its completion.

Why does it matter to understand the Gospels in this way? Simply, the Gospels are not disinterested history but rather have a clear theological goal and a formative purpose. The Gospels are not the mere history that other apostles build on to teach theology in the rest of the New Testament. They are historical, and the apostles do reflect on the Jesus traditions for their theological and moral teachings, but the Gospels themselves are also theological documents with the specific goal of inviting people to become disciples of Jesus. The Gospels are kerygmatic—they are preaching, teaching, and calling people to follow Jesus. Additionally, this message is set into the larger story of the world as told in the Old Testament, with a clear past and a promised future. According to Christianity, Jesus’s story is the epicenter of God’s work in the world. It completes and consummates what began at creation. At the same time, Jesus inaugurates the final age, which is not yet completed. This is what the canonical Gospels are: the central stories about Jesus that tell what happened and why it matters, all with a call to become followers of the Jesus whom they are describing, creating a community around devotion and allegiance to him.2

Godspell

How Many Gospels Are There?

To many familiar with the Bible this may seem like a trick question. The obvious answer seems to be “four.” This is the correct answer to the question of how many Gospels became recognized as canonical and thereby authoritative. But in the early centuries of the church there were actually many accounts of Jesus’s life and teaching beyond these four, some of which even took titles such as “Gospel of Peter” or “of Thomas” or “of Mary,” and even “Gospel of Judas.” Some of these were books that have survived only in partial fragments or in quotations found in other writings. Some accounts probably were only oral or short notebook-like collections of Jesus’s sayings. Luke refers to the fact that “many have undertaken” to produce an account of the events surrounding Jesus and that he himself has researched many before writing his own (Luke 1:1–4).

These other writings all came to be called apocryphal Gospels (or noncanonical Gospels), though they vary quite a bit in terms of form, reputation, influence, and value. Sometimes these texts have sayings that are very similar to the canonical Gospels and probably derive from them. Other elements of these apocryphal Gospels are clearly distinct from orthodox Christianity and reflect alternative readings of Jesus, such as Gnosticism, a religion that emphasized levels of secret “knowledge” (Greek, gnōsis) that people had to be initiated into. Many of these texts are not really Gospels at all in terms of the bios genre. Rather, some of them are merely collections of sayings, such as the Gospel of Thomas, and oddly share the title “Gospel.” Others are prequel stories about Jesus’s parents, birth, or childhood, such as the Protevangelium of James, or expansions of Jesus’s passion, such as the Gospel of Peter.

As centuries passed and Christianity became more widespread and influential, many other supposed Gospels came into being, representing different views and goals. Additionally, an alternative to the four was created by the second-century theologian Tatian (probably under the influence of Justin Martyr), called the Diatessaron (“through four”). This impressive work was a harmony—an attempt to make one story out of the four overlapping but distinct Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Whether it was meant to supplant or to support the recognized four canonical Gospels is not entirely clear. But we do know that it was influential in some parts of Christianity (especially Syria) but eventually was rejected in the broader church in favor of maintaining the four distinct witnesses.

The four Gospels that the church recognized as canonical rose to the surface because of their close connection to eyewitness testimony and because of their literary and theological clarity. Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are understood to be given by God and therefore authoritative. They are the canonical Gospels and consequently are set apart from any other writings and sayings about Jesus. Moreover, this canonization of the four creates a new relationship among them. Rather than just having four distinct Gospels, the early church thought and spoke about these writings as the singular Gospel given according to four witnesses.

Thus, the answer to the question of how many Gospels there are depends on what one means by the question. If one means, “How many people attempted to write down stories and sayings about Jesus?” the answer is “many.” If one means, “How many of these accounts are recognized in the church as canonical and thereby authoritative?” the answer is “four.” But if one means, “How did the church talk about these canonical accounts?” the answer is “ as one”—they understood that God gave one Gospel in four forms, enabling a quadrophonic hearing.

The Gospel of Thomas

The Book of Four Books

How Do the Gospels Relate to One Another?

We have just noted that very early on in the church the four canonical Gospels were recognized as authoritative and distinct from other writings. They are seen as one Gospel in four forms. Below we will discuss more fully the significance of this singular Fourfold Gospel Book. Before doing so, however, we must explore another question. It concerns the literary and historical relationships of the four Gospels to one another.

While it is impossible to know the precise details of how Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John came into being, we can piece together a number of plausible ideas. First, we know that Jesus’s actions and sayings first spread by word of mouth. Even during Jesus’s ministry, word about him spread so far and wide that it became difficult for him even to enter a village without being overwhelmed by crowds (Mark 2:1–2). These oral traditions continued and expanded after Jesus’s death and resurrection and the explosive growth of the church at Pentecost and beyond.

Ancient cultures (like many today) valued and maintained complex oral traditions with remarkable artistry and accuracy. In first-century Judaism, and subsequently in early Christianity, scribes memorized, interpreted, recorded, and taught the message of the faith. As time passed, and influential people passed away, many of these memorized sayings and interpretations were codified and written down. In Jewish tradition the record of different rabbis’ interpretations of Torah are written down in the Mishnah, a book that helped people to study and live according to God’s laws (halakah). Stories about things the rabbis did (haggadah) and things they said about Torah were remembered and then written down in the Talmud and Midrash. The development of the Gospels as written texts about the rabbi/sage Jesus likely followed the same pattern. Jesus’s deeds and words were memorized, organized, interpreted, and then eventually written down by his disciples, particularly those with some scribal education, or dictated to scribes. We can think of the Gospels as halakah and haggadah from Jesus, written in the style and language of the Greek bios.

With the recognition of this oral-to-written progression, the question remains: What is the relationship of the four Gospels to one another? They certainly all drew on the oral (and eventually written down) snippets of Jesus’s teachings and deeds. But beyond that it seems apparent that there was also a literary relationship between the Gospels, most clearly between the Synoptic Gospels—Matthew, Mark, and Luke. While each of these Gospels contains stories that are unique to it, the vast majority of their accounts overlap significantly. This overlap extends beyond general information about Jesus to the specific ordering of groups of stories, as well as very specific wording at several points. In other words, the Gospel writers apparently happily depended on the other accounts already written (recall Luke 1:1–4).

Parallel Sequence of Stories in the Synoptic Gospels

| Story | Mark | Luke | Matthew |

| Jesus’s teaching in Capernaum | 1:21–22 | 4:31–32 | |

| Jesus’s healing of demonized man | 1:23–28 | 4:33–37 | |

| Jesus’s healing of Peter’s mother-in-law | 1:29–31 | 4:38–39 | 8:14–15 |

| Jesus healing and exorcizing—summary | 1:32–34 | 4:40–41 | 8:16–17 |

| Jesus leaves Capernaum | 1:35–38 | 4:42–43 | |

| Jesus preaching in Galilee—summary | 1:39 | 4:44 | 4:23 |

| Miraculous catch of fish | 5:1–11 | ||

| Jesus heals a leper | 1:40–45 | 5:12–16 | 8:1–4 |

| Jesus heals a paralyzed man | 2:1–12 | 5:17–26 | 9:1–8 |

| Jesus calls Levi to follow him | 2:13–17 | 5:27–32 | 9:9–13 |

| Question about fasting | 2:18–22 | 5:33–39 | 9:14–17 |

| Question about plucking grain on the Sabbath | 2:23–27 | 6:1–5 | 12:1–8 |

| Question about healing on the Sabbath | 3:1–6 | 6:6–11 | 12:9–14 |

| Healing by the sea—summary | 3:7–12 | 6:17–19 | 12:15–16 |

| Jesus chooses the Twelve | 3:13–19 | 6:12–16 | |

| Source: Adapted from Robert Stein, The Synoptic Problem (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1994), 35. | |||

This insight is not just a modern notion; it was recognized and understood in the ancient church. One of the clearest and most influential explorations of the relationship of the Gospels to one another can be found in Augustine’s Harmony of the Gospels. Augustine, like most Christians up until the twentieth century, believed that the Gospels depended on and built on one another’s writings in the canonical order. Thus, Matthew wrote first; Mark wrote a brief version of Matthew; Luke used both Matthew and Mark in his work; and, finally, John provided a very different but complementary perspective.

Scholarly work in the modern era has led most interpreters of the Gospels to believe that Mark was written first and the others followed. There are differences of opinion about the relationship between Matthew and Luke: some say Matthew used Luke, and others that Luke used Matthew, while yet other scholars believe that both used a common source (called Q, from the German word Quelle, “source”). Regardless, the point remains the same: the Gospel writers were aware of one another and depended on one another’s work, not to supplant those who came before them, but to expand and to complement. The words of the Fourth Gospel’s epilogue sum up well the joy the early church found in recognizing the richness of the four interrelated Gospels: “Jesus did many other things as well. If every one of them were written down, I suppose that even the whole world would not have room for the books that would be written” (John 21:25 NIV).

Figure 5.1. Plaque with the Lamb of God on a cross between symbols of the Four Evangelists (1000–1050) [The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917.]

What Is the Fourfold Gospel Book and Why Does It Matter?

As noted above, for much of the church’s early history the four canonical Gospels were thought of primarily not as individual accounts but rather as a beautifully diverse unity, as one single Gospel given through four inspired witnesses. The word “gospel” (euangelion) was used in the singular form as the title to the collection of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John in one book.

Figure 5.2. This book-cover plaque with Christ in majesty (eleventh century) shows the Four Symbols of the Evangelists: the eagle (John), the human (Matthew), the ox (Luke), and the lion (Mark). [The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917.]

Ancient Christians called this the Tetraeuangelion (Greek) or Tetraevangelium (Latin). We may now call it the Fourfold Gospel Book. The idea that this book was four-in-one was communicated not just through the title and the frequent binding of the four accounts into one manuscript, but also through pictorial images. The Fourfold Gospel Book was represented ubiquitously through what are called the Four Symbols of the Evangelists. The Four Symbols were based on the four winged creatures surrounding God’s throne in Ezekiel 1:4–14 and retooled in John’s Revelation (Rev. 4:6–8). These creatures—a human, lion, ox, and eagle—are likely meant to stand for the highest representatives of distinct areas of God’s creation: humanity, the wild, the domestic beasts, and the birds of the air. Early Christian theologians and artists used these memorable images to describe the diversity within the unity of the Fourfold Gospel Book. Whether it be in marble carvings, paintings, frescoes, altar pieces, architectural forms, or book covers, the Four Symbols appear regularly as figures of Matthew (human), Mark (lion), Luke (ox), and John (eagle), witnessing to Jesus, the Word of God. Less commonly, but closely related, one also finds this relationship depicted through a tetramorph, a combination of the four creatures into one image. These artistic renderings make a strong theological point that church fathers such as Irenaeus, Jerome, and Augustine explained: the four Gospel writers have distinct voices and perspectives, but all are faithfully pointing to the one Jesus.

Figure 5.3. This tetramorph column from the parapet of a pulpit (ca. 1302–10) by Giovanni Pisano portrays a man (Matthew) with a lion (Mark) and ox (Luke) on each leg and an eagle (John) lectern that rested on top (only the wings remain). [The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Rogers Fund, 1921.]

Beyond the widespread use of the Four Symbols in Christian art, many theologians from ancient times until now have written on how each individual Gospel contributes to the Fourfold Gospel Book. For example, according to Augustine, Matthew provides the human lineage of Jesus, Mark is a mere epitomizer of Matthew, Luke shows us the priestly lineage of Jesus, and John reveals Jesus as the eternal Word of God.3 The Jesuit scholar Carlo Martini suggested that the four Gospels serve as manuals that correspond to four distinct phases in a disciple’s conversion and maturation, beginning with Mark, who leads to conversion, followed by Matthew the catechist, then Luke-Acts, and finally John.4 Frederick Dale Bruner creatively offered several metaphorical ways to think about the relationships of the four Gospels to one another: Mark is for evangelists, Matthew for teachers, Luke for deacons or social workers, and John for elders or spiritual leaders.5 Francis Watson follows the patristic habit of highlighting how each Gospel account begins and uses this to recognize distinct contributions of each: Matthew highlights that Jesus was a Jew, and it is through this Jewish Jesus that the gospel comes to the world; Mark emphasizes that the way of Christ is one of repentance and baptism; Luke highlights Mary as the ideal reader of the gospel story; high-flying John provides a vision of God through the Word that has become flesh.6 From a literary and theological viewpoint, Mark Strauss summarizes the unique contribution of each Gospel this way: Matthew presents Jesus as the Jewish Messiah who fulfills Old Testament hopes, Mark portrays Jesus as the suffering Son of God, Luke shows Jesus as the Savior for all people and all nations, while John highlights Jesus as the eternal Son of God.7

Other ways of relating the four Gospels to one another could be given beyond these examples, but the point remains the same: throughout the church’s history Christians have recognized one Gospel given in four forms, each with distinct perspectives, voices, and contributions while speaking in quadraphonic harmony.

How Did People in the Past Interpret the Gospels?

As we have noted, Christianity is concerned not merely with certain teachings but also especially with a certain person, Jesus the Christ. Therefore, the Fourfold Gospel Book played the central role in the experience of the earliest Christians. The apostles’ teachings, including the circulated letters from Paul, Peter, James, John, and others, were very important. But they were seen as supplements to the main focus of Christian gatherings: hearing about Jesus’s words and deeds, worshiping the Triune God in song, and sharing meals and goods with one another as each had need. This is precisely how Justin Martyr described early Christian gatherings.8 These oral and written stories and sayings eventually become codified in the four canonical Gospels and then in the Fourfold Gospel Book. The Gospels became the Magna Carta or Mayflower Compact of the Christian community.

Because of this, by the second century AD there were countless homilies and treatises written about the Gospels, sealing their place of priority in the church. In Greek first, then in Latin and other languages, church leaders and theologians produced massive, learned commentaries that unpacked the teachings of the Gospels. Examples include Origen’s Greek commentary on Matthew, much of which has been lost, but enough remains to show the care and skill that went into interpreting the Gospels.

Another way in which we can see evidence of the importance of the Gospels is in the writings of Christianity’s opponents. Christianity began as a peasant Jewish sect on the remote eastern end of the Roman Empire, but it quickly became an urban, gentile, and empire-wide faith. As a result, educated Roman elites began to take notice, and, with considerable irritation, they often attacked Christianity as being foolish, deceptive, and self-contradictory. One such writer was Celsus, whom we know about because the Christian scholar-theologian Origen wrote an important work titled Contra Celsum (Against Celsus), which seeks to answer Celsus’s charges against Christianity. The point is that, whether in commentaries and sermons by Christians or in works written by Christianity’s opponents, the Gospels were seen to be central because Christianity is rooted in what Jesus said and did, above all else.

Juvencus’s Epic Poem on the Gospels

Celsus’s Attacks and Origen’s Response

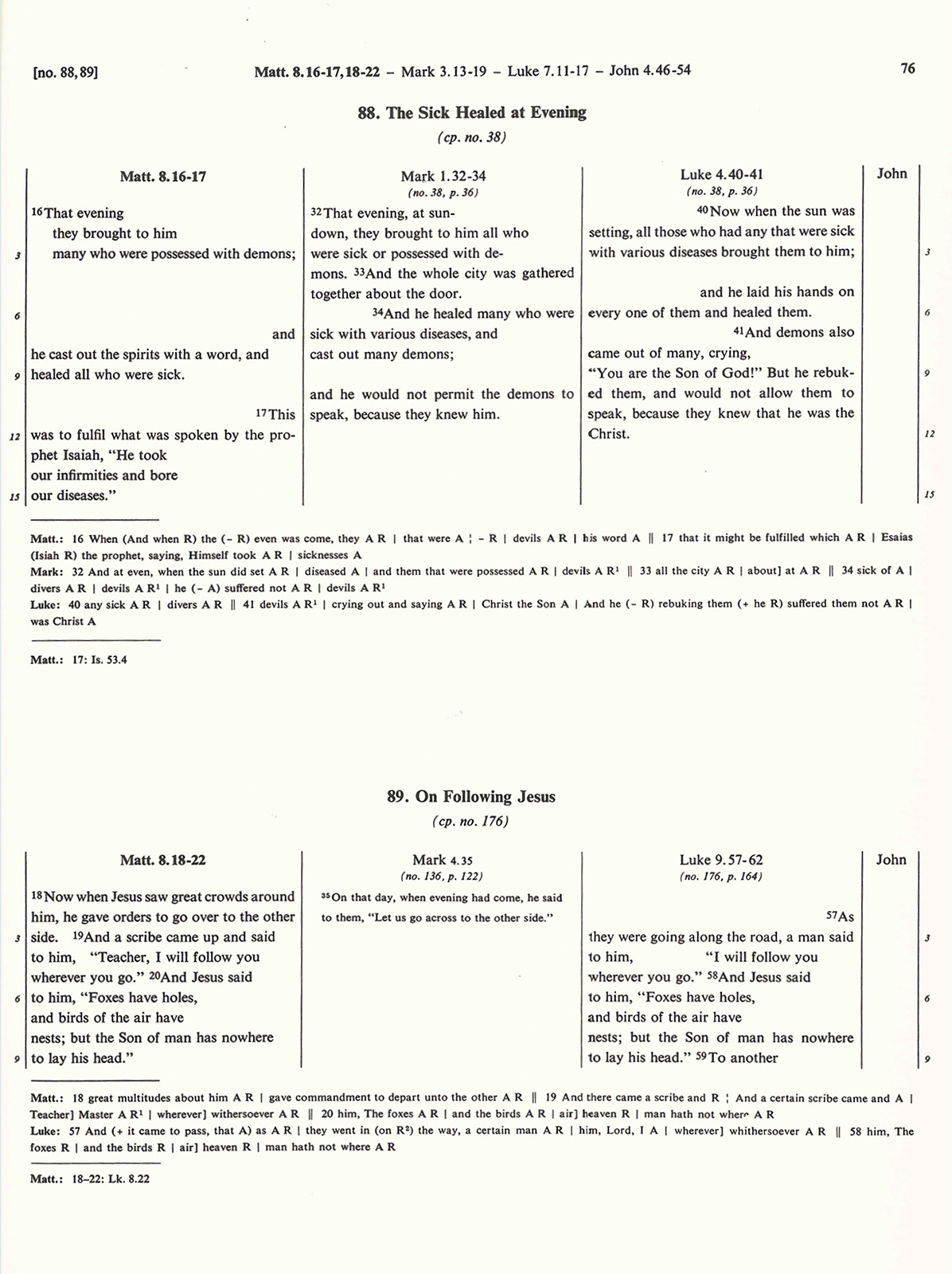

In addition to commentaries on the Gospels, another important aspect of Gospel reading in the ancient world was influenced by the Eusebian canon tables.11 In the early AD 300s the Christian scholar Eusebius created a cross-reference system for reading the Gospel stories in dialogue with one another. He numbered the stories throughout the Gospels and then assigned a set of numbers that show which stories have parallels in the other Gospels. These were collated into ten tables, or “canons,” that readers could use to make connections between parts of the Gospels within the Fourfold Gospel Book. Eusebius did not collapse the Gospels into one but continued the tradition of maintaining the diversity within the unity of the four Gospels. At the same time, his work encouraged a canonical way of reading the Gospels—not just vertically (reading each Gospel from top to bottom) but also horizontally (reading the Gospels across the pages in dialogue with one another). This tradition has dominated the way the Gospels have been treated in sermons, commentaries, and theological treatises of the church throughout most of its history.

Figure 5.4. These canon tables (folios 1v–2r) from a Carolingian Gospel Book (825–50) compare similar passages from the four Gospels. [The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Cloisters Collection and Director’s Fund, 2015.]

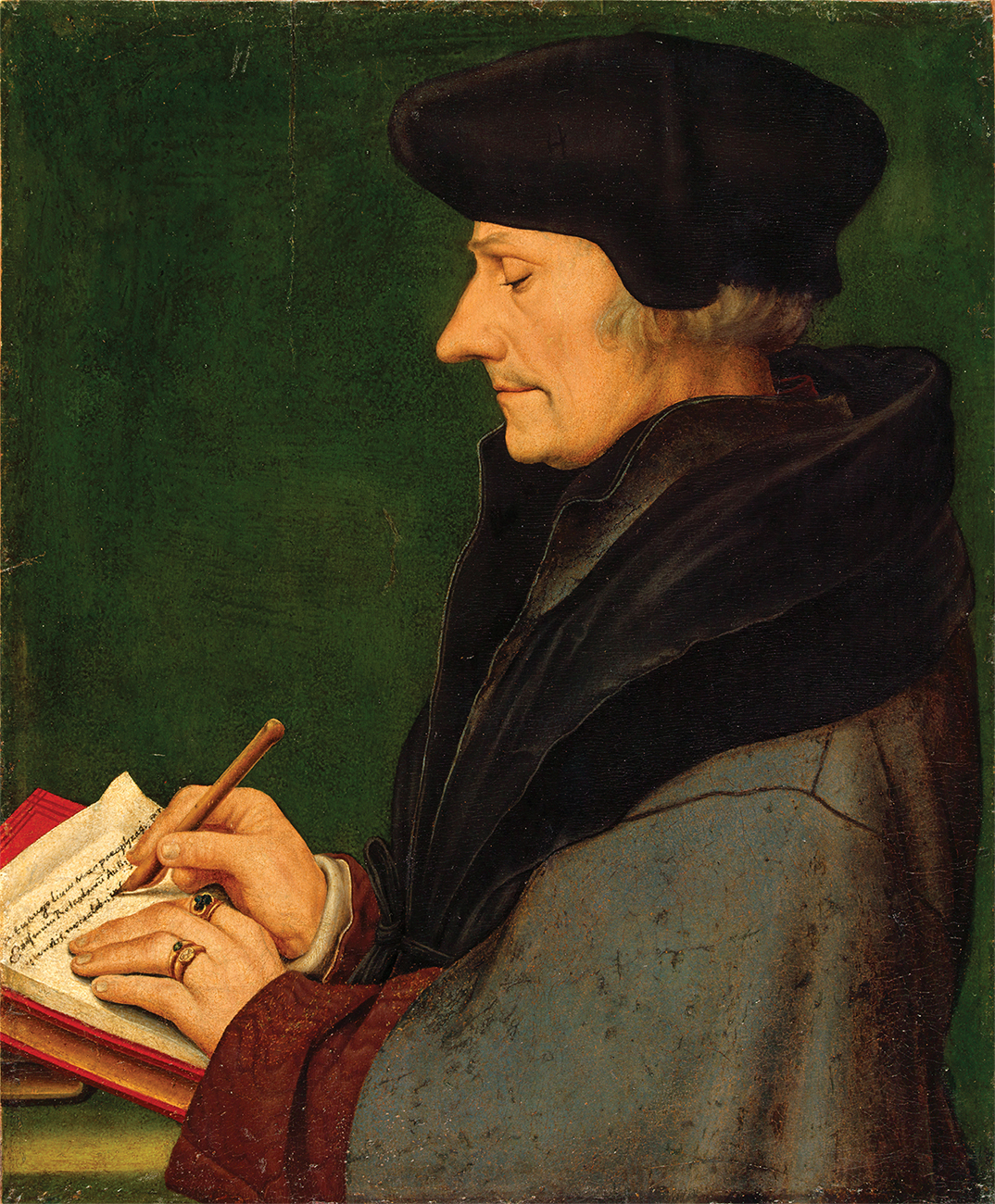

In Europe, the age of the Renaissance (ca. 1300–1700) introduced a new set of scholarly habits that also affected the reading of the Gospels. In this era, philology (the study of words) and the reconstruction of history became more of a focus, sometimes in conflict with long-standing traditions in philosophy and theology. One of the greatest minds in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was Erasmus (1466–1536), a Dutch Christian scholar who produced, in addition to many other works, one of the first scholarly printed editions of the Greek New Testament. This renewed interest in discovering the original texts affected the reading of the Bible and contributed to the world-shaking events of the Protestant Reformation (1517–1648). Reformers such as Luther, Calvin, and Zwingli renewed interest in preaching from the biblical texts and writing commentaries, including on the Gospels. In this era the Synoptic Gospels typically were treated together in a harmony while the Gospel of John was treated separately. For some of the Reformers the Gospels took a back seat to Paul and his letters because of the sharp theological debates of the day.

Erasmus’s Paraphrases

Figure 5.5. Desiderius Erasmus by Hans Holbein the Younger [Kunstmuseum Basel / Wikimedia Commons]

How Do Modern Scholars Interpret the Gospels?

The past 250 years in Western civilization have seen an explosion of specialized knowledge and scholarship unlike any other time in human history. This is not to say that there wasn’t great learning before this time period; there was. In fact, the technology and learning that we experience in the modern era came into being because of developments in the medieval and Renaissance eras and the rise of universities throughout Europe. But in the past 250 years many areas of scholarship have developed increasingly specialized theories and methodologies that have their own ways of reading the Gospels. There are several modern approaches (typically called forms of “criticism”), each of which offers its own perspective on how to interpret the Gospels. We will address here form criticism, source criticism, redaction criticism, literary criticism, and reception history.

The form-critical approach to reading the Gospels started as a method of analysis in Old Testament studies and was then adopted by many Gospels scholars in the early part of the twentieth century. Form criticism seeks to identify the different types (“forms”) of literature within the Gospels (parables, wisdom sayings, miracle stories) and speculate on what must have been happening in the church that would lead people to value and retell these stories. For example, Jesus’s saying about not putting new wine into old wineskins (Mark 2:22) is interpreted as reflecting a debate in the early church about the role of Judaism and the law in the Christian faith. The advantage of this kind of reading of the Gospels is that it helpfully identifies the fact that there are different genres within the Gospels, often collected together into units, and that these do in part reflect ideas that were important to the early church. The problem with form criticism, and the reason many have abandoned it today, is that its scholars often were overconfident in their assertions that the Gospel writers created the stories about Jesus for the purpose of addressing problems in the church. This approach is not very plausible historically, given that communities of faith cared very much about the eyewitness truthfulness of the stories about Jesus.

Source Criticism

Source criticism deals with the literary relationships of the Gospels to one another: Who wrote first and who used whom as sources? Source criticism is not actually a modern critical method in the same way that the others under discussion here are. As noted above, the question of what order the Gospels were written in, and how they relate to one another literarily, was something that was pondered by the ancient church. The canonical sequence of the Fourfold Gospel Book was considered the order in which the Gospels were written: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, one building on the others.

In the modern era, interest was rekindled in the literary relationship of the Gospels to one another, utilizing some new tools, and with differences of opinion about what these relationships are. Most scholars came to believe that Mark, not Matthew, was the first written Gospel. Additionally, scholars began to talk about Q, the supposed source that stood behind the large amount of material shared between Matthew and Luke. Over the decades different scholarly camps have evolved around these issues, with heated debates about whether Q ever existed, what order the Gospels were written in, and what role oral traditions played.

Parallel Gospel Stories

Figure 5.6. Sample Page from Aland, Synopsis of the Four Gospels [Synopsis of the Four Gospels, edited by Kurt Aland, 15th edition, © 2013 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft Stuttgart. Used by permission.]

In the mid-twentieth century Gospels scholars began to pay more attention to the role of the Gospel writers—not just as collectors of stories but as skillful editors (German, Redaktor, “editor”). Based on the newly dominant theory that Mark was the first Gospel written, scholars made increasingly sophisticated arguments about Matthew’s and Luke’s theological points by examining how they had adapted and modified Mark and the other materials they had before them. For example, when comparing Matthew’s and Luke’s accounts of Jesus’s temptation, redaction critics can note that one of the authors changed the order of the temptations from the other to emphasize different theological ideas: bread, temple, worship (Matthew) versus bread, worship, temple (Luke). This way of reading the Gospels—paying attention to the editorial activity of the Gospel writers and extrapolating theological points from this—became the predominant mode of Gospels interpretation throughout the last half of the twentieth century.

Literary Criticism

Beginning in the last twenty-five years of the twentieth century, while redaction-critical approaches dominated Gospels scholarship, other scholars began to focus on the Gospels as literature. This focus on the text of the Gospels as writings, rather than how they came to be written (as in form-, source-, and redaction-critical approaches), was part of a larger trend in the academic study of literature in general. The broad umbrella of literary criticism includes methods of interpreting the Gospels by attending to how they tell their story, including analysis of plot, structure, and character development. Literary-critical studies are conducted with varying degrees of sensitivity to historical context. For some scholars, the Gospels are studied only as pieces of literature. For others, the historical and sometimes the canonical context are factored into literary analysis, and these approaches are sometimes referred to as composition criticism or as a form of biblical theology.

Peter as a Character in the Gospels

Reception History

In recent years scholars have begun paying more attention to how the Gospels were read in the past, especially before the modern era. Good scholarship has always been aware of other interpreters’ views, but the recent focus on reception history is an exercise in rediscovering voices and perspectives that have long been lost or overlooked. This approach is rooted in a greater awareness of each interpreter’s situatedness in his or her own culture. Countless commentaries and homilies on the Gospels have never been translated from Greek or Latin into modern languages. Many scholars are now producing translations of such texts and study how the interpretations by earlier readers of the Gospels offer insights into their own culture and time as well as ours. For example, reception-history study of the Great Commission (Matt. 28:16–20) reveals that most interpreters throughout the church’s history did not think that this command applied to anyone but the original apostles. Only much later, with people like William Carey, did missionaries regularly use these verses to motivate their international missions.

All these modes of modern inquiry into the Gospels (as well as others we have not discussed) have something to offer. These various ways of reading the Gospels provide certain vantage points by asking different questions of the text, some focusing on how the Gospels came into being, some on how they function as literature, and some on how people have read them over the centuries. None of these methods stands alone or gives a comprehensive reading of the Gospels. Rather, each should be utilized for what it can offer without exclusion of others.

How Do We Read the Gospels as Christian Scripture?

In addition to the assorted ways that scholars have read the Gospels we can and should ask whether there is a distinctly Christian way of reading the Gospels—whether by scholars or not. Is there a mode of reading the Gospels as Christian Scripture?

Yes. There is a mode of reading the Gospels as Christian Scripture that accords with why and how the Gospels were written. This kind of reading is not opposed to a scholarly reading. Indeed, the best reading of any text, including the Gospels, will gain insights from any number of scholarly methodologies. But a Christian reading of the Gospels will pursue specific goals and manifest certain sensibilities. We can summarize this way of reading the Gospels under three categories.

Reading the Gospels to Understand the History of Jesus

Because Christianity is based on a person more than on certain ideas, a Christian reading of the Gospels starts with a focus on who the real Jesus was, in actions and words. The Gospel writers desired to faithfully record the things that Jesus said and did so that people’s faith in him would be based on the truth (Luke 1:1–4; John 20:30–31). Central to this faithful witness is the end of the story—Jesus’s last week, his suffering, death, and resurrection—that each Gospel highlights through literary space and details. The opposite of this kind of Christian reading would be a mode of interpretation that is skeptical of the faithfulness of the witness or that reads the Gospels as mere symbols or universal ideas divorced from real history.

Reading the Gospels within the Context of the Rest of Holy Scripture

A Christian reading of the Gospels also interprets them as part of the canon of Holy Scripture. First, the Gospels are understood as part of the larger story of the Jewish Scriptures, beginning with creation and focusing on the history and hopes of Israel. Each of the Gospels in its own way indicates that they are to be read as the consummation of the story to which the Old Testament points. Second, reading the Gospels well means interpreting them both as individual books and as part of the Fourfold Gospel Book. Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John should be read individually as theological biographies, but their placement in the Christian canon means that they simultaneously have a dialogical relationship with one another, enabling comparison and harmonization. Third, a Christian reading of the Gospels regards them in conjunction with the rest of the apostolic writings in the New Testament. While the New Testament Letters often address different issues and use different vocabulary, a Christian reading understands the deep unity within this harmonious diversity. The opposite of this kind of reading would interpret the Gospels in isolation from the rest of the canon and would fail to see a fundamental unity of thought and vision.

Reading the Gospels to Become a More Faithful Disciple

Ultimately, the most important aspect of a Christian reading of the Gospels is to read them with the purpose of becoming a more faithful disciple. The Gospels were written as theological biographies, not just to teach history and theological truths but also to provide models for emulation and avoidance. This is why narratives are written—so that readers may reflect on their own lives through observing the lives of others. The stories of Peter’s denial and restoration, or of the Canaanite woman’s faith, or of Judas’s betrayal and regret are far more powerful than the nuggets of doctrinal truth that we may summarize them with. The biography subtype of narrative literature focuses primarily on one person as a model for emulation, but other characters in the story often serve this purpose as well. The Gospel biographies particularly invite readers into a life of discipleship that is rooted in Jesus’s teaching. Disciples learn to be in the world by having their thoughts shaped by teaching while their habits are shaped by models. All of this is founded on the core idea of biblical ethics: godliness means learning to imitate God himself (Lev. 19–20; Matt. 5:48; 1 Cor. 11:1; 1 Thess. 1:6).

Figure 5.7. The Denial of Saint Peter by Caravaggio [The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Herman and Lila Shickman, and Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1997.]

Throughout the Gospels Jesus is engaged in a project of resocialization of humanity’s values and sensibilities. For example, the poor and lowly are valued, treating others with mercy and compassion is exalted, and love is the ultimate mark of what it means to be a Christian. This resocialization often is counterintuitive but is taught powerfully through the stories of the Gospels. The goal of this is to make and shape disciples. Thus, the most faithful reading of the Gospels is a personal one that submits to Jesus’s call. One can read the Gospels as literature, as pieces of first-century history, as a contribution to comparative-religion studies, or any number of other ways. While these modes of reading are not wrong or useless, they are not ultimately in accord with the purpose of the Gospels or the life of Christian discipleship. The Gospels are kerygmatic in nature, meaning that they are constantly calling for a faith response on the part of readers. “Let anyone who has ears to hear listen” (Mark 4:9).

Christian Reading Questions

- Why do you think it is important to understand the genre of the Gospels?

- Compare and contrast the four types of criticism discussed in this chapter (form, source, redaction, literary). What do you think are the pros and cons of each?

- Off the top of your head, make a list of ten characters from the Gospels. Draw a spectrum between “flat” and “round” (based on the descriptions of different types of characters from this chapter). Now plot each character on this spectrum. Why did you place each character where you did?

- What goes into a Christian reading of the Gospels? Read John 2–3 and reflect on understanding this particular passage under each of the three categories of a Christian reading of the Gospels.