CHAPTER EIGHT

The Gospel according to Luke

Orientation

Bible trivia question: Who wrote more of the New Testament than any other single person? The apostle Paul? Jesus’s beloved disciple John? Both are good answers, but both are incorrect. Paul wrote more books of the New Testament than anyone else, and John wrote a lengthy Gospel. But the winner of the “Most Words Written by a Single Author in the New Testament” award goes to Luke, coming in with a solid 27 percent of the verbiage of the New Testament. (Paul has 23 percent, and John has 20 percent.) Luke, an educated gentile physician, who often accompanied Paul on his missionary journeys, wrote two lengthy and polished volumes that are crucial to the New Testament canon. These books are really two parts of one big story. The first book is Luke’s contribution to the Fourfold Gospel Book, the Third Gospel account. The second volume, which we call the Acts of the Apostles, overlaps with the conclusion of his first book—the story of Jesus’s post-resurrection ascension. Acts continues the story of Jesus by following the lives of his disciples and the growth of the Christian faith. Together these stories, which we refer to as Luke-Acts, give us fifty-two fascinating chapters, over a quarter of the New Testament writings.

Figure 8.1. An ox, the symbol of Luke’s Gospel, from a book cover (1200–25) [The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931.]

The Historical Origins of Luke

Though Luke wrote a two-part story (Luke-Acts), throughout most of the church’s history the Gospel according to Luke has not been read in direct tandem with Acts but rather has been clustered with its canonical Gospel siblings (Matthew, Mark, John). Early in the church’s history the Fourfold Gospel Book was organized in a 3 + 1 pattern, with the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke) joined together with John. This is followed by a separate collection—Acts plus the General Letters and Paul’s Letters (including Hebrews). This puts the Gospel according to Luke into closer connection with the other three Gospels than with his second volume, Acts. While there are important insights that come from reading Luke and Acts together, there are also advantages to thinking about Luke in conjunction with the other Gospels.

If we read Luke’s Gospel account in dialogue with his canonical brothers, what kind of story does Luke give us? We can use three words to describe Luke: original, mimetic, challenging.

Original—Around 40 percent of Luke’s Gospel is not found in any of the other Gospels, including many beloved parables and stories. Luke is not merely rehashing Mark and Matthew, but rather makes many original contributions. The source of these materials seems to have come from Luke’s own research.

Mimetic—Luke tells his stories about Jesus in ways that deeply imitate and evoke key stories from Israel’s history (mimesis). From the birth narratives to the post-resurrection road to Emmaus, Luke skillfully spices his stories with tastes of God’s work in the world before Jesus, inviting his readers to taste and see that Jesus is truly the fulfillment of all of God’s promises from the past.

Challenging—Luke radically reverses his readers’ values and expectations. Luke regularly shows Jesus turning the world upside down by valuing the poor, the outcasts, and the devalued, showing them filled with the Spirit and worshiping God truly.

Luke’s story has three major sections, all centered on Jerusalem, which is known as the city of David and the center of Jewish worship and culture:

Luke 1:1–9:50: This section shows who Jesus is, beginning with his origins and focusing on his ministry of teaching and healing.

Luke 9:51–19:27: This section begins with Jesus resolutely setting a course to go to Jerusalem. This lengthy portion includes much of Luke’s original and most memorable stories as Jesus faces increasing opposition by the Jewish leadership.

Luke 19:28–24:53: In this final part of Luke’s story Jesus arrives in Jerusalem and spends his last week teaching his followers and interacting with his opponents. The book concludes with Jesus’s trials, death, and resurrection, culminating with his appearance to several disciples, explaining how to understand all that God has done.

The Structure of Luke

Exploration—Reading Luke

The Overture

READ LUKE 1:1–2:52

These opening chapters are familiar to many people because of the oft-retold Christmas story. Many have heard the story of Mary and Joseph trekking to Bethlehem, unwelcome and without shelter, Mary giving birth to a son with animals all around, laying him to sleep in a feeding trough. Carols like “Away in a Manger” and “Silent Night,” along with holiday images of angels and stars and shepherds, come straight from Luke 2.

But this Christmas-pageant part of the story is only that—part of the story. Taken together these first two chapters of Luke are less about Christmas night and more like the overture to a Broadway musical: they introduce the main themes and ideas, even if it is unclear what these themes and ideas mean and what the story will look like. In Luke’s overture-like introduction we quickly learn that God is on the move and is about to fulfill the hopes of his people. Through a series of poems and songs we are told that God is about to turn everything upside down: a barren old woman and a virgin both become pregnant; a young, lowly girl is said to be most blessed of women and shows great faith, while a seasoned Jewish priest is struck dumb; unsavory shepherds are the first honored guests for the birth of a king; and a twelve-year-old boy astonishes the temple priests with his great wisdom. All of this and more create an expectation of wonder for the story that Luke is about to tell. This story is not boring. The main character, Jesus, is going to upend the world.

Mary’s Song in Western Music

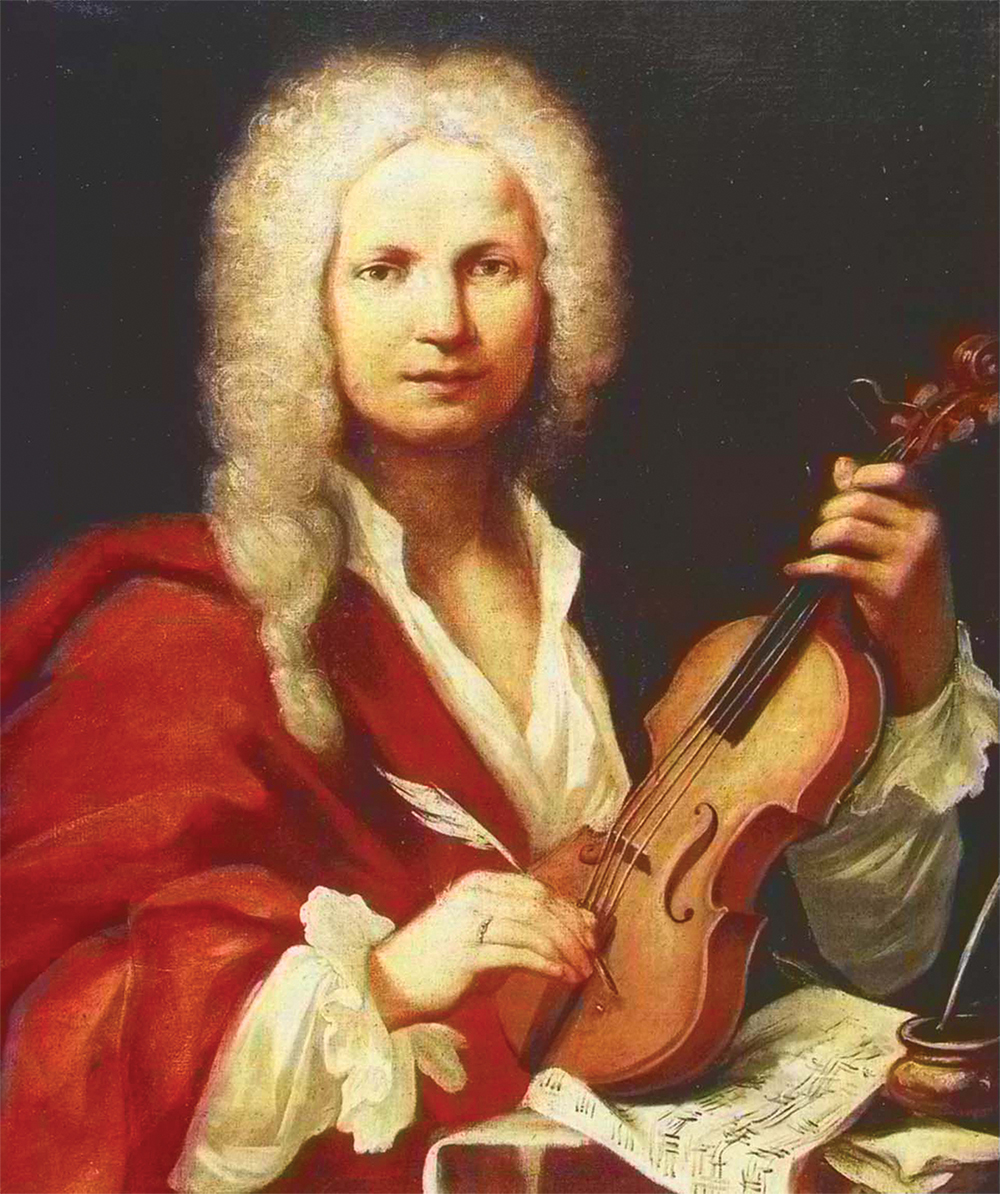

Figure 8.2. Portrait of Antonio Vivaldi by unknown artist [International Museum and Library of Music / Wikimedia Commons]

The Kingdom of God in Action

READ LUKE 3:1–4:44

Luke’s prologue focuses on the preparation and birth of Jesus followed by one story about the twelve-year-old Jesus in the temple (2:41–52). The story then jumps ahead about eighteen years (3:23) and provides additional stories about Jesus’s preparation before he calls his first disciples.

Consistent across each of the Gospels is the appearance of John the Baptizer as the herald and forerunner of Jesus. Luke’s reporting of John gives us more information on some points and less on others. We don’t get any of John’s interaction with Jesus regarding his baptism (3:21), but we are given more detail about the content of John’s preaching. John was sent to preach “a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins” (3:3), which is applied to specific life situations such as sharing one’s goods (3:10–11), being honest in financial dealings (3:12–13), and not abusing one’s authority and position (3:14).

After Jesus’s genealogy traces him all the way back to Adam (3:23–38), we finally see Jesus in action and hear his voice. Jesus is shown to be Spirit-filled and powerful, successfully outwitting the devil’s temptations (4:1–13), teaching with bold authority in the synagogue (4:14–30), rebuking and exorcising demons (4:31–37, 41), and healing people of all kinds of illnesses (4:38–40). All this activity is summarized as “the good news about the kingdom of God,” which Jesus has come to bring (4:43).

The Genealogies of Jesus in Matthew and Luke

The Powerful Messiah at Work in Galilee

READ LUKE 5:1–9:50

This long section constitutes the first major portion of Luke’s account, offering a rapid-fire series of stories that describe Jesus’s ministry in Galilee in the northern part of Israel, before Jesus begins his planned move south to Jerusalem (9:51).

This section begins with the calling of the first disciples—Simon Peter, James, and John—who would forever remain the innermost circle of Jesus’s followers (5:1–11). In 6:12–16 Luke lists the group of twelve disciples appointed by Jesus from among the large group of followers. Between these two listings of disciples Luke tells a series of stories that position Jesus within Israel’s tradition, while showing him to be unique and powerful: Peter’s calling mimics the calling of Isaiah (5:1–11); the leper’s cleansing is connected to the Mosaic commandments (5:12–15); a paralytic’s healing is the occasion of Jesus proclaiming forgiveness of sins (5:17–26), which he says is why he has come (5:27–31); and Jesus explains the true meaning of the Sabbath, claiming to be the Lord of the Sabbath (6:1–11). All of this can be described with the metaphors of Jesus as the long-awaited bridegroom and the new wine that cannot be contained in old wineskins (5:33–39).

Figure 8.3. The Annunciation (1481) by Sandro Botticelli [Uffizi Gallery / Wikimedia Commons]

The second part of this section focuses on Jesus’s authority as the Messiah. First, he is shown to be a powerful wisdom teacher (6:17–49). This is followed by a series of remarkable stories of Jesus’s power over creation: Jesus heals the centurion’s daughter from afar (7:1–10); he raises a widow’s son and a synagogue leader’s daughter from the dead (7:11–17; 8:49–56); he stills a violent storm by merely rebuking the wind and waves (8:22–25); he heals three seemingly unhealable people, a man possessed by a legion of demons (8:26–39), a hemorrhaging woman (8:42–48), and a demon-possessed boy (9:37–43); and finally, Jesus miraculously multiplies food for famished followers in the wilderness (9:10–17).

All of this confirms the claim made that Jesus is the God-sent Messiah (9:18–20) who is the glorious Son of God, honored by Moses and Elijah, who will bring about the new exodus (9:28–36).

The Calling of Messengers

Meals with Jesus

Encouragement amid Dark Warnings

READ LUKE 9:51–13:35

We have now entered Jesus’s journey to Jerusalem (9:51–19:27), where Luke packs in many of the stories that are unique to his account. The first half of this journey is framed with references to Jerusalem (9:51 and 13:34–35). In between we hear teaching directly from Jesus more than stories about him.

The tone of this section focuses on a wide variety of stark warnings. The sense of urgency and the call to be alert are woven through a large number of images. These include warnings about counting the cost of following Jesus (9:57–62) while also being aware that this is a wicked generation heading for judgment (10:12–16; 11:29–32; 12:54–59; 13:1–5). In fact, a large part of Jesus’s teachings here urge watchfulness because of the return of the Son of Man, who will bring judgment on the unrepentant. Jesus describes this as the return of unclean spirits (11:14–26), as woes on the Pharisees and scribes (11:37–52), as a foolish rich man losing his soul (12:13–21), like the unexpected return of a master who finds his servants to be unfaithful (12:35–48), as a time coming with weeping outside of the kingdom feast (13:22–30), and as Jerusalem as a desolate city (13:31–35).

Maker of Heaven and Earth

Yet this dark foreboding is peppered with words of encouragement to Jesus’s followers. We see that Jesus gives power to his multitude of disciples to be his witnesses and overcome Satan (10:1–20). He calls his followers blessed because they are given the ability to believe in the Father and the Son (10:21–24). Jesus teaches his disciples how to pray to God as their Father, promising that they will receive what they ask for, even as a father gives good gifts to his children (11:1–13). Similarly, Jesus’s disciples should not live in anxiety, because their Father will provide for their needs (12:22–34).

This juxtaposition of warnings and encouragement shows that Jesus has come as a sword that will divide the world into two groups: those who believe in him and those who don’t (12:49–53). There is no middle ground.

Selling One’s Possessions

Blessing and Breaking Bread

Overturning Human Values

READ LUKE 14:1–19:27

Jesus continues his long journey south to Jerusalem, and Luke records an interesting collection of interactions that Jesus had with people along the way. There are some stories that remind readers of Jesus’s miraculous powers (14:1–4; 17:11–19; 18:35–43), but most of the stories instead focus on a different kind of wonder. With parables and actions, Jesus repeatedly proves that the kingdom of God is going to look very different from human rule.

What are some of the differences in kingdom values? First on the list is wealth. The story of the great reversal of fates for the rich man and Lazarus (16:19–31) is shocking to any hearer and challenges our love of money and neglect of the poor. Jesus returns to this theme when interacting with a noble Jewish leader whom Jesus calls to give up all his wealth to become a disciple. When the man responds with grief rather than joy, Jesus shocks everyone by pronouncing that possessing wealth makes it extremely difficult to enter the kingdom of God. Rather, the truly rich are those who have given up whatever they must to become Jesus’s disciples (18:18–30). This upheaval of human values is modeled in the memorable story and parable that culminates this section. The story details the conversion and salvation of the disreputable tax collector Zacchaeus. This wealthy man sees Jesus, and when he does his love and drive for wealth no longer control him. As a result, he gives away half of all he owns to the poor and recompenses fourfold any whom he had wronged (probably most people!). Jesus describes this response as evidence of a lost man being saved (19:1–10). The accompanying parable that concludes Jesus’s journey to Jerusalem likewise focuses on wealth and how people respond to what they have been given. To those who honor God with their wealth and talents much will be given; to those who do not, just judgment is God’s response (19:11–27). Jesus says all of this most simply with the statement that people cannot serve two masters, both God and money (16:13).

In addition to challenging the human obsession with wealth, Jesus shows that in God’s kingdom those who are valued as worthy of most honor are often the opposite of those that human society honors. This often overlaps with wealth, as can be seen in the stories of the rich man and Lazarus and of Zacchaeus, but not always. Jesus uses the example of seating at a dinner party to confront humanity’s propensity to boost personal honor rather than humbly seeking to bless society’s dishonored ones (14:7–14). Some such people are highly praised by Jesus, contrary to their rank in human eyes. These include the widow whose faith in God makes her pray persistently (18:1–8), the tax collector whose humility and repentance grant him a relationship with God while the holy Pharisee remains outside (18:9–14), little children who model what it means to enter the kingdom (18:15–17), and a blind beggar who comes to see God (18:35–42).

Jesus also shows through these stories that God loves to redeem and restore the lost, not condemn them. This theme is closely related to the topic of honor and shame. The stories of Zacchaeus (19:1–10), the ten lepers (17:11–19), and the tax collector (18:9–14) all show this. The series of parables in 15:1–32 most clearly shows this theme of joyful restoration instead of judgment. God is shown to rejoice over the now-found state of the lost sheep (15:3–7), the lost silver coin (15:8–10), and the lost son (15:11–24). The problem is that people—especially religious people who value external obedience—don’t often share God’s joy in this. To drive this point home, Jesus adds another part to the parable of the lost son: the story of the older brother who refuses to rejoice in the restoration of the lost son and brother (15:25–32). This serves as a challenge and invitation to reorient one’s values toward what God loves and rejoices in.

As Jesus nears Jerusalem for the last week of his life, his conflict with the religious leaders is increasing. Luke shows us that this conflict is rooted in a different set of values and loves. This is summed up well in 16:14–15: “The Pharisees, who were lovers of money, were listening to all these things and scoffing at him. And he told them, ‘You are the ones who justify yourselves in the sight of others, but God knows your hearts. For what is highly admired by people is revolting in God’s sight.’”

The One-in-Three Parables of Luke 15

Short Zacchaeus and Ancient Physiognomy

The Transfiguration

READ LUKE 19:28–21:38

The final stage of Jesus’s ministry has now been reached, and it takes place, not accidentally, in Jerusalem. Since the time of Israel’s greatest king, David, Jerusalem has been the center of Israel’s faith. The temple was built there, and Jews to this day make pilgrimage to their holy city. Jerusalem and its temple are also the center of the future hope for all Jewish people who are still looking for the return of the Davidic Messiah.

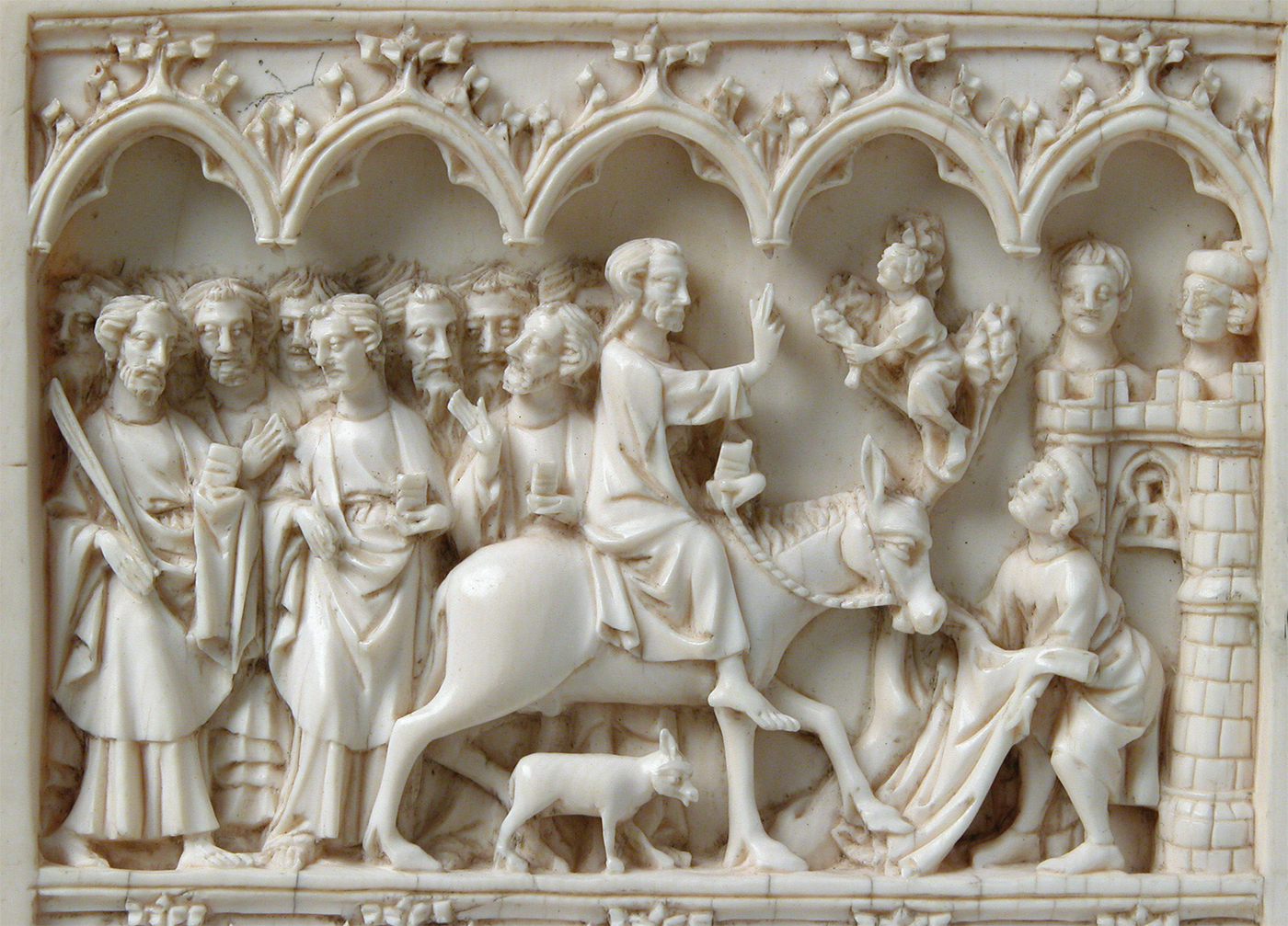

This is why Jesus, who knew himself to be the true Messiah, purposefully arrives in Jerusalem, prepared to complete the mission that God the Father has sent him to do. His entry into the city is intentionally symbolic. He arranges to go up through the Jerusalem gates riding on a colt. As he enters the city, his disciples and the massive crowds who have experienced his teaching and healing, and who believe him to be the promised king, cannot help but burst into spontaneous worship, laying their cloaks on the road before him in honor and shouting praise to God for the blessing of the return of the king (19:28–38).

This triumphal entry, which the church continues to celebrate to this day as Palm Sunday, is a picture of Jesus’s regal glory. But this event also reveals the sad irony that even though Jesus came to rescue his people and reign as their king, many of the most religious Jewish people of the day did not rejoice. Instead, they were offended. Over the shouts of praise they command Jesus that his disciples must stop this inappropriate scene (19:39). Jesus responds that if his disciples are quiet, the stones themselves will cry out with praise (19:40), meaning that their actions are right and appropriate—he is the promised Son of David!

This story of a king being rejected by his subjects concludes not with Jesus shooting lasers out of his eyes or mocking his enemies but rather with Jesus weeping. With great compassion he sees the city of David as a place that is facing destruction because of the rebellion of its people. Because the Jewish leaders did not recognize that God himself was arriving in Jesus, the city itself will be destroyed (19:41–44).

Jesus the Sacrificial Priest in Luke

This is yet in the future. For now, Jesus is in Jerusalem, his place of rightful enthronement, for one last time before he will be killed. After this disputed entry into the city, Jesus focuses his time and teaching on the temple, the place where heaven kisses earth and God is present with his people. The actions and sayings that Luke records for us from 19:45 through 21:38 happen over the course of several days. Jesus’s pattern was to go to the temple area early each morning to speak to the crowds and then to retire each night to the hill called the Mount of Olives (19:47; 21:37–38). Over the course of these long and tense days, what does Jesus say and do?

Jesus the king’s first action is shocking. Rather than grabbing political power in the palace, Jesus exercises not his royal role but his priestly and prophetic callings. He goes to the center of Jewish worship, where the priests make daily sacrifices on behalf of God’s people, and he disrupts and challenges their authority. With a zeal that matches any of the most dynamic Old Testament prophets, Jesus expels merchants and proclaims the corruption of the temple, calling the practices there thievery rather than prayer (19:45–46).

Not surprisingly, conflict with the established leaders in Jerusalem erupts. The crowds are fascinated by this vigorous teacher, but the priests, teachers of the law, and the Jerusalem leadership knew immediately that this troublemaker must be killed (19:47–48). First, they question the source of his authority, but he stumps them in this (20:1–8). Jesus then goes on the offensive with a pointed parable that shows him to be the faithful heir of God’s kingdom and the leaders to be usurpers (20:1–18). Unlike Jesus’s otherwise esoteric parables, this parable they fully understand he has spoken against them, thus stirring up their anger and resolve even more to silence him (20:19).

The infuriated leaders then try a different tactic: entrapping Jesus by his own words. First they try to trick him into offending either the Roman overlords or the Jewish conservatives over the issue of paying taxes (20:20–26). Jesus astonishes them with his brilliant answer (20:24–25). They are equally unsuccessful with a thorny theological question. Their attempt to entrap him between two different Jewish groups on the question of marriage in the resurrected state also fails miserably (20:27–40).

Figure 8.4. A scene of the entry into Jerusalem from a diptych with scenes from Christ’s passion (ca. 1350–75) [The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Rogers Fund, 1950.]

Once again, Jesus goes on the offensive and poses to the leaders a theological dilemma that focuses on the mystery of a divine mediator between David and Yahweh, speaking of himself as the solution, David’s Lord (20:41–44). They are unable to answer, and Jesus issues a dire warning that people should beware of such respected teachers of the law who seek praise and honor rather than the humble truth. Only punishment awaits them (20:45–47). By way of contrast, Jesus commends a lowly widow who is not seeking praise but rather who humbly gives to the Lord with a whole heart (21:1–4). This is the kind of person Jesus commends.

The remainder of Jesus’s temple-based daily teachings focus not on the present but on the future, on a time when God will bring strong judgment on the unrighteous actions and attitudes of those who are leading and controlling the heart of Israel’s worship. It is not pleasant to hear Jesus’s teachings about this coming judgment. Beauty will become destruction, and peace will become war. Jerusalem, its people and its place, will be trampled and desecrated (21:5–27). But even amid this darkness Jesus offers hope to his disciples: these are the signs that redemption is drawing near (21:28), that God’s kingdom is now fully at hand (21:31). The appropriate response to these images of judgment, then, is not despair but watchful care, anticipating Jesus’s return (21:34–36).

With these daily doses of conflict with the religious leaders in the heart of Jerusalem, Jesus’s die is cast. Sovereignly and intentionally he has fulfilled his role as God’s prophet, knowing that the result will be his own destruction.

Denying Christ in the Early Church

The Fulfillment of a Crucified King

READ LUKE 22:1–23:56

Up to this point Luke’s story has contained moments of foreboding darkness—predictions of suffering and forewarnings of judgment. But here the story takes its darkest turn. This “crucial” section—meaning both central and crucifix-shaped—begins with Jesus being betrayed by one of his closest twelve companions (22:1–6) and ends with Jesus bloodied, bruised, and dead, his body sealed in a stone tomb, wrapped in linen cloths, and covered with spices (23:50–56). This was truly the most momentous twenty-four-hour period in history.

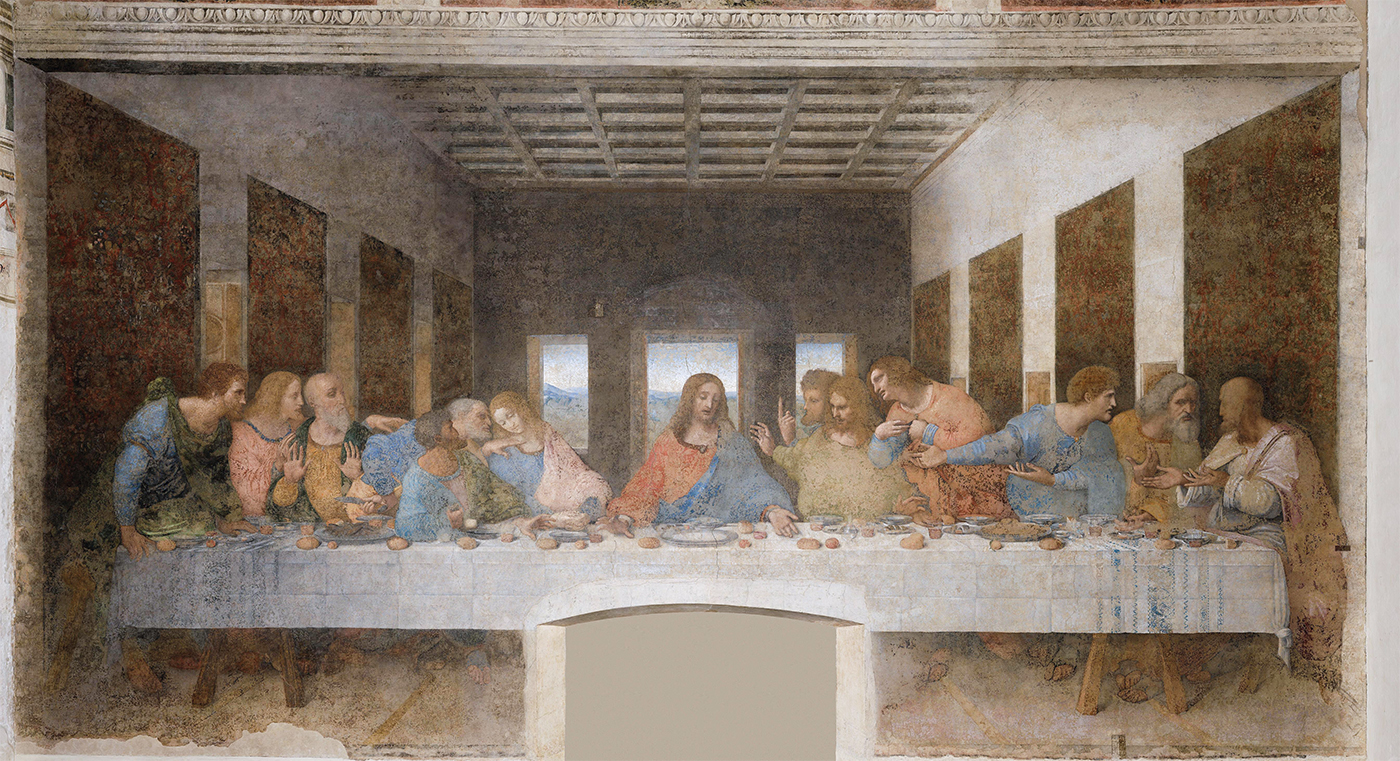

Woven throughout these events, the repeated theme focuses on the kingdom of God. We see this first in the story of the Last Supper of Jesus and the twelve disciples. Luke, who often is sparse with details compared to Matthew and Mark, provides a rather lengthy account of Jesus’s sayings on his last night with his disciples. Jesus chooses to celebrate the high Jewish holiday of Passover with his chosen family of faith, not his biological family, and he deepens the significance of this meal by expanding its meaning. This meal celebrating the past memory of the exodus of Israel from Egypt becomes a forward-looking celebration of the coming kingdom of God. Jesus speaks passionately and personally about his desire to celebrate this feast with his own disciples before the darkness of his suffering descends, because, he states, he will not eat this meal with them again “until it is fulfilled in the kingdom of God” (22:16), “until the kingdom of God comes” (22:18). When the disciples begin disputing among themselves who will be the greatest (presumably as they think about God’s coming kingdom), Jesus contrasts God’s kingdom with human kingdoms by stating that the servant and the lowly one will have great standing (22:24–27). The kingdom talk continues with the staggering statement that the Father has appointed Jesus over his kingdom and that Jesus is now doing the same for his disciples, so that they may dine with him and rule over all Israel (22:28–30).

The Resurrection of the Body

The theme of Jesus as the king continues throughout the rest of the stories. When Jesus is betrayed and arrested, he must stand before the rulers of the area, first the Jewish leadership, then the Roman governor Pilate, and then Herod the king. In each case the dispute about Jesus’s identity as the Messiah/King is forefront. The chief priests demand for him to be clear about whether he thinks he is the Messiah, and he answers affirmatively; he is the Son seated at the right hand of God (22:66–71). The priests use this as the opportunity to get him arrested by the Romans. Pilate asks him if he is the king of the Jews, and Jesus again responds positively (23:1–3). When Jesus is next dragged before Herod, the guards dress him in an elegant robe, mocking his claim to be king (23:11). Jesus finally is crucified, with the charge against him printed for all to see: “This is the King of the Jews” (23:38). The onlookers, both Jewish and Roman, mock him about this, challenging him to show his supposed power and save himself (23:35–37). The two criminals hung on either side of Jesus both speak to him about his role as king, one mocking him (23:39) and the other pleading for Jesus to remember him when Jesus comes into his kingdom (23:40–42). Finally, when Jesus’s body is removed from the cross and prepared for a burial worthy of royalty, we are told this was accomplished through the power and influence of Joseph of Arimathea, a believer in Jesus who himself was “looking forward to the kingdom of God” (23:51). This dark twenty-four-hour story shows Jesus to be the crucified king.

Figure 8.5. The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci. Da Vinci’s famous painting is not meant to represent what a dinner in the area of first-century Palestine would have looked like, but rather depicts a meal setting of his own time. In the first century, diners would have reclined with pillows on the floor around low tables (triclinium in style). [Wikimedia Commons]

The Last Supper and the Passover Haggadah

READ LUKE 24:1–53

This final chapter of Luke’s Gospel is entirely unique—we know of these fascinating stories only because of his account. These stories are not only fascinating and unique but also essential: in this final chapter Luke ties together and pushes forward several truths that are central to the reason he has written his Gospel. Specifically, this chapter emphasizes that Jesus is the fulfillment of all the promises of God, and that in order to understand the message of the whole Bible one must see Jesus clearly. Along the way, readers are given one of the fullest accounts of Jesus’s resurrection and post-resurrection activities (about the same length as John 20–21).

I Believe in the Holy Spirit

As dark and devastating as Luke 22–23 was, Luke 24 is alive and enlightening. Luke does not record the instant of Jesus’s resurrection from the dead, but what happened as a result of this epic moment in history.

First, on the third day after his death, some of the women disciples (who are shown as more consistently believing than the male disciples) go to the place of Jesus’s burial. They are shocked to find not a sealed cave, but rather the tomb opened and empty. They meet two angels who proclaim that Jesus is now among the living. These faithful women report this to the amazed apostles lingering in Jerusalem (24:1–12).

Second, on the same day, two of Jesus’s disciples were making the seven-mile walk from Jerusalem to Emmaus (24:13). The resurrected Jesus caught up and walked with them, and he enters into a dialogue without revealing his identity. The hidden Jesus begins as the one who appears ignorant of recent events but soon becomes the teacher. He explains to them that all these events make total sense if one understands “Moses and all the Prophets” correctly, as all pointing to God’s promised Messiah (24:25–27). Then, in a beautifully symbolic act, while Jesus is breaking bread to eat with them, God suddenly opens their eyes and they realize this man is not just any fellow believer; this is the risen Jesus himself (24:30–31)! Jesus vanishes, and these disciples run to the eleven apostles in Jerusalem to report what happened.

Third, building on the other two events, Jesus then appears to the apostles and disciples gathered in Jerusalem. Naturally, they are shocked and doubt what they are seeing. Jesus graciously responds by speaking peace to them. When this is not enough to quell their fears, he eats a piece of broiled fish (24:36–43). With his identity and physical presence established, he once again explains to the stunned believers how everything that has happened to him is the promised fulfillment of all that God said and did in the past. As a result, he commissions them to go forth to every nation as his witnesses and proclaimers of repentance and forgiveness of sins (24:44–49).

Figure 8.6. The Drogo Sacramentary (ca. 850) is an illuminated manuscript that includes this depiction of the ascension of Christ. [Bibliothèque Nationale de France / Wikimedia Commons]

This chapter ends in a way that strongly foreshadows and anticipates Luke’s second volume, Acts. Jesus tells his disciples to stay in Jerusalem until they receive power from heaven, anticipating the giving of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost in Acts 2. He then gives them his last blessing while physically with them and is carried into heaven before their eyes. This long and eventful Gospel ends with Jesus’s followers full of joy and worship, heading toward Jerusalem to be his witnesses (24:48–53).

It would be difficult to overestimate the importance of Luke 24 to Christian theology. This powerful conclusion to Luke’s Gospel highlights the significance of Jesus’s bodily resurrection, the necessity of God revealing himself so that people can understand the truth of the Bible’s whole message, and the role of Christians as joyful witnesses to God’s grace toward the whole world.

Luke, 1 Corinthians 15, and the Resurrection Body

The Theology of the Ascension

Implementation—Reading Luke as Christian Scripture Today

The Gospel according to Luke looks to the past, the present, and the future. Looking backward, Luke emphasizes repeatedly that through Jesus Christ God has fulfilled all of his many promises in the Jewish Scriptures. Looking to the future, Luke emphasizes that Christ’s resurrection inaugurates a new era in history, the age of the Spirit, which looks forward to the time when Jesus will return to complete his work in the world. For the present Luke emphasizes the ongoing work of God in the world through the church that is faithful to Christ’s teachings. This present work begins to unfold in Luke’s second volume, the book of Acts, and continues to the present day. The Gospel of Luke serves as a guide to train the sensibilities, values, and habits of Christ’s disciples as they engage and seek to transform individuals and, thereby, society itself. Jesus invites people into an alternative society/kingdom, where the outcast, the poor, the nobodies are valued and even exalted. To be a disciple is to enter into and participate in this way of being in the world.

- Read through Luke 1–2 and note themes and ideas that Luke is trying to communicate. Then note ways in which these themes appear in other places in Luke’s Gospel.

- Note the many physical descriptions of characters in Luke’s Gospel. How do you think Jesus’s interactions with people with many different physical descriptions (e.g., Zacchaeus) shine light on the purpose of his ministry?

- Listen to Johann Sebastian Bach’s musical setting of the Magnificat, using translated lyrics. How do you think the music corresponds to the Magnificat as Luke wrote it in Luke 1:46–55, and what effect does it have on you as the listener?

- Read Luke 4:16–30. What did Jesus mean by saying that the Scripture he read had been fulfilled today? What echoes of the Scripture that Jesus quotes here do you see throughout the rest of Luke’s Gospel?