Paul’s Hardships (6:3–13)

Having summarized the nature of his message and ministry (5:10–6:2), Paul now focuses on the character of the minister. By means of the familiar hardship catalog, he demonstrates his altruistic motives and self-sacrificing labor.

As servants of God we commend ourselves in every way: in great endurance; in troubles, hardships and distresses (6:4). In 4:8–9, 6:3–10, and 11:23–33 Paul presents the Corinthians with his apostolic credentials, a partial list of hardships he has endured on their behalf. These “hardship catalogs,” as they are called, were part of the standard repertoire of Stoic and Cynic instruction and served to demonstrate the moral character of the teacher. Through these inventories of adversity the teacher sought to exemplify three primary virtues: fortitude, self-sufficiency, and indifference to external circumstances.

In using this form of argument Paul also offers himself as a model to emulate, but he qualifies these virtues in significant ways. Fortitude and strength, perhaps; but more important, weakness (11:30; 12:10). Dependence on self? Absolutely not! Rather, dependence on God (6:6–7; 12:9). Unaffected by circumstances? Not really. While patiently enduring pain, Paul is not ashamed to admit profound emotion (1:8–9; 6:9; 11:28). Most of the following hardships are repeated in 11:23–33, and the details of each ordeal will be discussed there. At the present we will focus on comparing the perspective of Paul’s hardship catalogs with some of his Greco-Roman contemporaries.

In beatings, imprisonments and riots; in hard work, sleepless nights and hunger (6:5). “Hardships … put virtue to the test” and successfully enduring hazardous trials demonstrated the philosopher’s strength and superiority.81 According to the Epitome of Stoic Ethics compiled by Arius Didymus (first century B.C.), the noble Stoic is “great, powerful, eminent and strong … because he has possession of the strength which befalls such a man, being invincible and unconquerable” (11g). In language similar to Paul, Epictetus refers to “exile and imprisonment, and bonds and death and disrepute” as matters of no concern.82

Like the Stoics, Paul believes physical hardships are of some value (1 Cor. 9:27; 1 Tim. 4:8), though his concern is not to parade Stoic bravado and claim “invincibility.” Rather, he needs to make the Corinthians aware—especially those who question his leadership—of his tireless labor on their behalf. Contrary to the Stoic emphasis on invulnerable strength, Paul focuses his attention on his weakness (see comments on 12:10).

In purity, understanding, patience and kindness; in the Holy Spirit and in sincere love; in truthful speech and in the power of God (6:6–7a). The ideal sage, according to popular Stoic (and Cynic) representation, is one who relies solely on his own inner resources to face the deprivations and calamities that fortune supplies. According to Stoic doctrine, “he makes the whole matter [of happiness] depend upon himself” and is enjoined by God, “If you wish any good thing, get it from yourself.”83 Paul, by contrast, is adamant that his strength rests in “the Holy Spirit … and in the power of God” (cf. 3:1–6; 12:9–10); this is the most fundamental difference between the valiant Stoic and the follower of Christ.

With weapons of righteousness in the right hand and in the left (6:7b). Military imagery occurs frequently in Paul’s letters, and the description here is of a well-equipped Roman legionary.84 The offensive weapon in the right hand is either a medium-length javelin (infantrymen carried two) or a short thrusting sword, while the left hand holds the defensive weapon, a sturdy shield. Roman field tactics called for both javelins to be discharged from a short distance, whereupon the soldier rushed upon the wounded enemy to finish him off with a quick thrust of his sword.

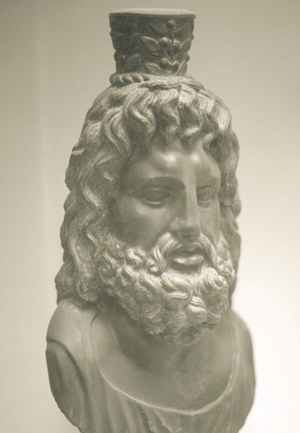

ROMAN WEAPONS

The Roman war god Mars with a shield in the left hand and a spear in the right hand.

Through glory and dishonor, bad report and good report; genuine, yet regarded as impostors; known, yet regarded as unknown; dying, and yet we live on; beaten, and yet not killed (6:8–9). In the ancient Mediterranean world, honor and shame were core values, and within the highly stratified social structure of Roman society a great deal of daily energy was expended avoiding shame and accumulating honor. As a group value, honor was gained through public recognition (formally or informally) of personal worth. In expressing his indifference to public opinion, Paul dons the mantle of the suffering sage willing to endure contempt for the good of the community. Such a role was actually honored in Mediterranean society, and contemporary philosophers often adopted this posture:

• Hunger, exile, loss of reputation, and the like have no terrors for [the noble sage]; nay he holds them as mere trifles.85

• These are examples of indifferent things: life, death, reputation, lack of reputation, toil, pleasure, riches, poverty, sickness, health.86

Sorrowful, yet always rejoicing; poor, yet making many rich; having nothing, and yet possessing everything (6:10). Once again, Paul’s argument reflects both continuity and discontinuity with his Greco-Roman contemporaries. Unlike the Stoic, who strove to “view with unconcern pains and losses, sores and wounds … wholly unchanged amid the diversities of fortune,” Paul freely admits his sorrow (cf. 1:8–9; 7:5; 11:28–29).87 The display of emotion during hardship was considered an indication of moral weakness, hence Epictetus extols the man “who though sick is happy, though in danger is happy, though dying is happy, though condemned to exile is happy, though in disrepute, is happy.”88 Yet Paul does advocate contentment in all circumstances (Phil. 4:11–13), and the final words of 2 Corinthians 2:10, “having nothing, and yet possessing all things” echo an important Stoic principle:

Alone and old, and seeing the enemy in possession of everything around me, I, nevertheless, declare that all my holdings are intact and unharmed. I still possess them; whatever I have had as my own, I have…. So far as my [true] possessions are concerned, they are with me, and ever will be with me.89

SENECA

The Temple of God and the Temple of Idols (6:14–7:1)

The plea of 6:1 not to receive God’s grace in vain is now given concrete expression in a prohibition against nurturing harmful relationships with unbelievers. Paul treated this topic in 1 Corinthians 8; 10:14–22, but apparently his advice was treated too lightly.

Do not be yoked together with unbelievers (6:14). The scene evoked by Paul’s words is less obvious to those living in industrialized Western societies, where a team of oxen plowing a field is an unimaginable sight. The term heterozygeō, to yoke differently, refers to placing two animals of different species under the same yoke (e.g., an ox and a donkey). The obvious difference in strength, height, and disposition could lead to disastrous consequences. Although one application of this verse relates to believers marrying unbelievers, Paul’s purview is much broader and includes all manner of spiritually detrimental social intercourse, especially pertaining to the practice of frequenting pagan temples (see below).

What harmony is there between Christ and Belial? … between the temple of God and idols? … Dear friends, let us purify ourselves from everything that contaminates body and spirit (6:15–7:1). In 1 Corinthians 8:1–13 and 10:14–30, Paul dealt extensively with problems relating to dining in pagan temples and eating meat sacrificed to idols. These activities were not simply a function of pagan religiosity from which the new believer could easily abstain. Rather, they were an integral part of the social fabric of Roman society and were often associated with the fulfillment of civic responsibilities. Since only the well-to-do had homes large enough for a formal dining room, the abundant temples of Corinth provided facilities for entertaining dinner parties. The related fees were naturally used for the support of the temple and cult. Numerous invitations to these ancient cocktail parties survive:

Herais asks you to dine in the (dining-)room of the Serapeion at a banquet of the Lord Serapis tomorrow, the 11th from the 9th hour.90

THE TEMPLE OF GOD AND THE TEMPLE OF AN IDOL

The Apollo temple in Corinth.

A model of the Jerusalem temple.

Drunkenness, gluttony, and sexual promiscuity were part and parcel of such affairs, and against this backdrop Paul’s harsh warning against the “contamination of body and spirit” (7:1) becomes more comprehensible.91 Also understandable is Paul’s insistence that Christ and Belial (Satan) cannot consort. Not only were offerings and toasts made to the god, but the deity was believed to be present at the meal and sometimes even sent the invitation: “The god calls you to a banquet being held in the Thoereion tomorrow from the 9th hour.”92 Given Paul’s conviction that the worship of pagan deities is actually the worship of demons (1 Cor. 10:20–22), no participation in such rituals could be tolerated. But in a culture where religion and the social order walked hand in hand, such separation was a delicate and dangerous task. It is not surprising that Christians were later charged with misanthropy, antisocial behavior.93

SERAPIS