Fig. 2.1 The funeral banquet. Greek wall painting from the Tomb of the Diver, early fifth century BCE. Location: Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Paestum. Source: © Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY.

Archaic Greece was a song culture. Whether performed publicly in a ritual context where it was complemented by choral dancing, or privately at a gathering of friends by a single artist, music was the chief medium of popular entertainment. The librettos of songs, bereft of their melodies, are mainly the texts that survive, often only in snippets and papyrus fragments. Metrically, they fall into two main categories: elegiac poetry, composed of recurrent couplets of unequal length (a line of six metrical feet followed by one of five) and accompanied by the aulos, a kind of double flute; and lyric poetry, arranged in various kinds of stanzas made up of short rhythmic phrases, sung, as the name indicates, to the lyre. Thematically, the genre to which a song belongs is determined by the occasion of performance: paeans are hymns of praise to Apollo, dithyrambs are choral songs for Dionysos, skolia are after-dinner songs, partheneia are songs for maiden choruses, iambs are poems of slander and abuse, and so forth (Fowler 1987: 90–101).

Since the use of writing was extremely limited, music was learned by ear. Solon, the leading Athenian statesman of his time (he served as archôn or chief official in 594/3 BCE), heard his nephew play a song of Sappho at a party and asked the boy to teach it to him, “so that,” he said, “I may learn it and die” (Ael. ap. Stob. 3.29.58). Access to literary culture, as distinct from formal education, was more catholic because literacy was not a requirement for artistic appreciation. Non-elites, slaves, and women would all have had access to myths, songs, and oral lore transmitted by word of mouth. Still, we have to imagine circumstances of performance quite different from those we associate with today’s mass-media entertainment. No electronic amplification, no CDs or MP3 files, no downloading from the Internet, of course, but also no mega-concerts with crowds of raucous fans in attendance. If poetry was sung before a large audience, the dignity of the event, almost always religious, guaranteed solemnity. Solo songs, or monodies, were performed in a more intimate venue, the dining room of a wealthy private house or a ruler’s palace, with only a group of invited companions present. Probably the nearest modern analogy to hearing a Sappho or an Alcaeus sing on those occasions would be the experience of listening to a folk guitarist in a small coffee house with a regular clientele. The artist knows many members of her audience personally, draws energy from their rapport with her, and tailors her recital to their interests and preferences. If she writes her own material, she may mention in her lyrics something familiar to her listeners. Such exclusive references do not limit the song’s popularity: when another folk singer incorporates one of her numbers into his own repertoire, he will usually preserve those allusions, even though his own audience may have to guess at their meaning. Thus songs still travel from artist to artist across the country, retaining elements of their original performance setting in re-performance, just as they did in antiquity.

Although the poetry of the archaic age could deal with many different subjects – warfare, religion, politics, philosophy, among others – love, and most frequently pederastic love, was its dominant concern. Our chief textual sources for the sexual attitudes and values of the archaic age are the lyrics of its love songs. They evoke the contradictory facets of erôs, its complex moods and sentiments, its mingled delights and pains, with metaphors that reverberate forcefully even when translated into an alien language. As scholarly evidence, though, this corpus of material presents serious difficulties. For example, we cannot take poets’ statements about themselves as autobiographical. The artist speaks of himself or herself in the first person, but in doing so steps into a role, taking on the persona of a “Sappho” or “Alcaeus” and re-enacting the utterances of that character (Nagy 1996: 216–23). Thus the “Sappho” whom Aphrodite accosts in Sappho fr. 1 V is a fictive construct, not the composer. Because it was meant to captivate and excite audiences, moreover, love lyric presents emotional suffering in grandiose terms, and because it assumes its listeners are of the same social position, with common values and experiences, it provides no historical framework for its content. Other materials that might help to fill in the contextual gap are lacking: contemporary historical accounts are non-existent and later testimony may be inaccurate, inscriptional evidence is scanty and the archaeological record contested. Yet we know that momentous social changes, including the rise of the polis, colonization and expansion of trade, new contacts with the Orient, the introduction of writing and coinage, fierce competition among elites for political power, and bitter class conflict all occurred during this 300-year period.

The first question we consider in the present chapter, then, is how such external factors affected the expression of erotic feelings in a sympotic setting, especially when the lover was speaking to his erômenos. A second, and closely related, question has to do with the privileged status of the pederastic bond in the archaic period. Why does it suddenly take on the importance it does in the poetry of the time? This requires us to examine the controversial thesis that posits a link between homoerotic relations and initiatory, or coming-of-age, rituals.

According to a commentator on Plato’s Symposium, the phrase “wine and truth” was proverbial for those who talked frankly while inebriated. To illustrate, he quotes the opening line of a poem by Alcaeus: oinos, ô phile pai, kai alathea, “wine, o dear boy, and truth” (fr. 366 V). Here, in a nutshell, is the essence of the early Greek symposium or drinking party: alcohol, candor in the presence of trusted companions, and a young man being coached in proper behavior by older members of the group. In these surroundings, poetry performed an educational function by affirming collective values, often through direct address, as in the two books of elegies attributed to Theognis of Megara (composing c.550–540 BCE). What must strike modern readers as odd is that the framework for such elegiac instruction is pederastic; the addressee – sometimes called “Cyrnus,” sometimes anonymous – is the speaker’s beloved, and many of the verses harp on the fidelity owed to one’s lover. Sympotic lyric can likewise address an erômenos, although it puts emphasis upon the speaker’s desire and longing rather than sending an overtly didactic message. Before we turn to examining the content and formulas of archaic love poetry, though, we must locate the symposium within its political context.

The origins of the sympotic gathering are plausibly traced back to the Homeric age (Murray 1983). Local kings competed for honor by entertaining lesser nobles with sumptuous feasts and giving them valuable gifts. Members of the propertied class repaid their hosts’ generosity by equipping a band of followers to accompany them on military expeditions. During the late eighth and early seventh centuries, as the polis society emerged, certain features of that Homeric way of life were transformed. Armies of heavily armored foot soldiers or hoplites, drawn from the citizenry, replaced elite troops, depriving the aristocracy of its primary civic function. Founding of overseas colonies brought about an expansion of trade, which in turn enriched a new social class of merchants and artisans. The introduction of coinage in the sixth century and its integration into the Greek economy was just as subversive of the preexisting state of affairs as foreign commerce, for it allowed low-status persons to acquire prestige goods by saving up money (Schaps 2003: 132). Coinage issued by city-states accordingly prevented wealthy nobles from monopolizing the circulation of precious metals through gift exchange (Kurke 1999: 6–23).

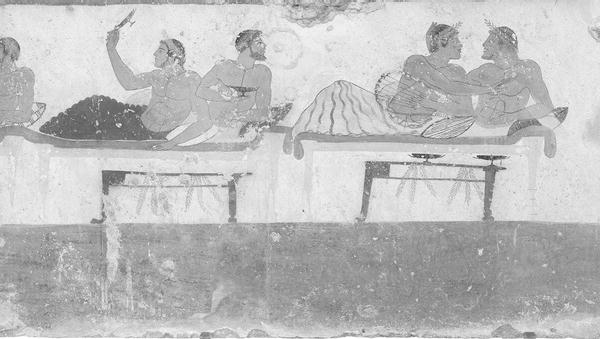

Over time, largely as a result of intermarriage, the nobility had acquired a disproportionate share of agricultural land, and, with it, political hegemony. With some exceptions, early archaic Greece was ruled by oligarchies, small blocs of wealthy landowning families. Sympotic culture arose in response to agitation against oligarchic privilege. As the urban middle class began to exercise its growing economic power, oligarchic families closed ranks, forming a tightly knit leisured class whose marriage and friendship affiliations crossed polis boundaries. Its political stance was conservative, hostile to developing democratic tendencies. The symposium became central to its cultured lifestyle. Special dining rooms were constructed in private houses, with space for between fourteen and twenty-two men, all facing each other to assist conversation. Here members of a hetaireia or private drinking club would discuss common political concerns while modeling masculine conduct for their erômenoi. The most famous visual depiction of a sympotic milieu actually comes to us from southern Italy (fig. 2.1). Painted on the inside walls of a stone sarcophagus at Paestum are scenes of drinkers reclining, playing kottabos (a game in which the dregs in the wine cup were thrown at a target), singing to the music of an aulos, and embracing.1

Fig. 2.1 The funeral banquet. Greek wall painting from the Tomb of the Diver, early fifth century BCE. Location: Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Paestum. Source: © Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY.

Within sympotic culture, some historians contend, two belief systems began to compete for authority. One was a “middling ideology” encapsulated in Hesiod’s Works and Days and propounded by iambic poets like Archilochus and Hipponax or moralizing elegists like Solon (Morris 1996: 28–31, 2000: 161–71; Kurke 1999: 25–7). The ideal member of the community is the metrios or “middling man,” the self-sufficient landowner and head of household. Although he mistrusts the poor, he likewise avoids greed, for excessive wealth breeds arrogance, lack of restraint, and disdain for the rights of others – the cardinal social and religious offense of hybris. This ideology, subsequently the source of Athenian democratic values (Morris 1996: 40–2), opposed itself to an elitist tradition of conspicuous consumption, for the beleaguered rich who felt threatened by social developments were demonstrating their pre-eminence through the use of expensive goods imported from the Near East. Imitating Oriental potentates, symposiasts lay on couches rather than sitting at table and delighted in vessels, perfumes, and finery of Lydian manufacture. Their poets celebrated a “cult of habrosynê,” or luxury infused with a refined sensuality (Kurke 1992). Eroticism became politicized, for the ostentatious diversion of energies and resources into appearance, dress, manners, and appreciation of the transient beauty of flowers and the human form, indulgences denied to the pragmatic middle class, found its natural sexual manifestation in nonreproductive congress (Morris 2000: 178–85). Thus this group of nobles escaped class tensions and reaffirmed among themselves their superiority to the dêmos, the “ordinary people,” through shared meals, drinking, song, and sex in a protected sympotic ambience (Arthur 1984: 42–3).

Once the aristocracy lost its military function, it turned to sport as its main focus of physical competition. The archaic age was the period when the great Panhellenic athletic festivals were instituted, beginning with the traditional founding of the Olympic Games in 776 BCE. Games were introduced at local festivals as well; the poet Pindar (518–438 BCE), who composed celebratory odes for victorious athletes, mentions some twenty such regional contests (Scanlon 2002: 29). Athletic pursuits were not confined to the elite: during the sixth century, many Greek communities laid out exercise grounds so that hoplites might keep themselves fit for battle. These were the forerunners of the gymnasium with its palaistra or wrestling court. However, the expense of intensive training ensured that participation in athletic contests, especially on the Panhellenic level, remained the province of the well-to-do until the classical era. Though the gymnasium was open to all citizens, then, its popularity as a site for elite pastimes, including pederastic courtship, explains its close association in Plato and other classical Greek authors with the aristocratic symposium.

One last consequence of the rise of the polis was the proliferation of unconstitutional dictators, whom the Greeks, borrowing a foreign word, called tyrannoi. The “tyrants” of the archaic age were not necessarily despots conducting a reign of bloody terror. Fierce rivalry for power and prestige among oligarchic factions within the state prompted successful coups by strongmen capable of putting a stop to civic violence, at least temporarily. Once established in power, many, like Pisistratus, who controlled sixth-century Athens, turned out to be benevolent rulers who respected traditional institutions and sought to promote the welfare of the citizens. To add luster to their communities, they sponsored religious festivals, undertook civic works projects, and invited leading artists, musicians, and philosophers to enjoy their hospitality. The sixth-century poets Ibycus of Rhegium and Anacreon of Teos were guests at the court of the tyrant Polycrates of Samos, and Anacreon was later patronized by the Pisistratid dynasty. In a manner reminiscent of Homer’s bard Demodocus, these poets provided banquet entertainment for the tyrant and his friends. Ibycus’ and Anacreon’s lyrics are characteristically sympotic in their focus on wine and love, but they lack the topical political commentary of Alcaeus’ and Sappho’s songs, which were composed for strictly private functions.

Because the language of Greek lyric evokes images as readily as emotions, many of its most compelling descriptions of love are visually metaphoric, with emblematic details taken primarily from the natural world. One of the commonest figurative spaces within which Aphrodite and Eros operate is the flowery meadow (Bremer 1975: 268–74; Calame 1999 [1992]: 153–7). Hera and Zeus’ rendezvous on the grassy slope of Mount Ida furnished the Homeric archetype for all such topographic descriptions. Many later episodes using a verdant meadow as backdrop do not feature consensual sex, however, but instead tell of adolescent girls forcibly inducted into womanhood. In the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, for example, Hades finds Persephone gathering flowers on the plain and snatches her up as she reaches for a beautiful narcissus (Hymn. Hom. Cer. 6–14). Meadows can be employed as a setting for rape or seduction because they belong to the realm of nature yet are accessible from the polis, situated as they are on its outskirts. In addition, they are the grazing-ground for domesticated beasts, especially horses. Properly the verb for “breaking” or “taming” a horse, damazein is the regular euphemism for defloration: virgins were considered “wild” because their sexual potential had not yet been harnessed, as it were, to producing children.2 Lastly, the heavily scented roses, hyacinths, and narcissi plucked by maidens in those surroundings are emblematic of the fates of unhappy youths who failed to make the transition from late adolescence to adulthood – such as Hyacinthus, Apollo’s beloved whom he killed by accident, or Narcissus, who wasted away after he fell in love with his own reflection.

Whenever a lyric composer alludes to a grassy or flowering field, that whole system of symbolic resonances is brought into play. Even without an explicit mention of erôs, then, the language is likely to have hidden sexual implications. One well-recognized instance is Sappho fr. 2 V, an invocation summoning Aphrodite to attend a festive celebration. Elsewhere the poet expresses deep yearning for several of her female friends, whom she refers to collectively as her “companions” (hetairai, fr. 160 V, cf. frr. 126, 142). Here the setting is a temple precinct and what remains of the text describes it in lush detail. First, we hear of a grove of apple trees and altars fragrant with incense, both to be expected near shrines of the goddess. Other natural features, however, mark the site as unique and blessed (5–11):

There cold water plashes through apple boughs,

and all the place is shadowed with roses,

and from the shivering leaves deep

sleep slips down,

and there a horse-pasturing meadow

blooms with spring flowers, and breezes

blow softly …

Apples, incense, roses, horses, the flowering meadow – each bears some relation to the cult of Aphrodite. All occupy a place in a network of erotic metaphors alluding to or symbolizing parts of the female body (Wilson 1996: 38). Thus the fleshy fruit of the apple (mêlon) and the folded petals of the rose can be used as analogues for the female genitalia, which explains their frequent occurrence in wedding songs. In Sappho’s poem, these concrete natural objects are brought into conjunction with a special mode of sleep (kôma), a trance-like state often induced by supernatural means (Page 1955: 37). This is the slumber Hypnos sheds upon Zeus after he has made love to Hera: “I have wrapped a soft kôma about him,” the god informs Poseidon (Il. 14.359). Through an imaginative, polysemous appeal to the senses of touch, smell, and sight, the description of the temple precinct evokes the corporal pleasures of lovemaking and repose after sex, becoming “an extended and multi-perspectived metaphor for women’s sexuality” (Winkler 1990: 186).3

Two lyrics by Anacreon illustrate how these tropes can also be deployed for invective purposes. In the first, the speaker addresses a reluctant girl, whose “skittish mind,” the commentator tells us, “he allegorizes as a horse” (PMG 417):

Thracian filly, why do you,

looking at me with suspicious eyes,

evade me pitilessly, and assume

that I have no skills?

Listen to me: I could easily throw

a bridle upon you

and working the reins bend you

around the limits of the course.

As it is, you graze in the meadows

and frisk, lightly prancing,

for you don’t have an expert rider upon you,

one who knows horses.

Riding is a standard ancient metaphor for sexual intercourse. Under cover of this extended conceit, then, the speaker is boasting about his masculine prowess. By comparing the girl who refuses his attentions to an untrained filly, he suggests that she does so from virginal modesty. Yet his addressee is obviously a prostitute, as her foreign origin indicates. While a respectable virgin in a meadow exposes herself to the threat of rape, the horse that ranges freely across the pastures of erôs is a figure for the woman already given over to promiscuity (Gentili 1988 [1985]: 186–94). The humor of the poem, then, is generated by maintaining two opposed readings of the girl’s conduct and character in play through one set of images. The same contrast between prostitute and virgin seems to function in a patchy and much-supplemented papyrus text (PMG 346 fr. 1):

… and your mother believes that

she nurtures you, keeping you

penned in the house.

But you […] browse upon

the fields of hyacinth

where Cypris has tethered

the … mares freed

from the yoke-straps …

In ancient Greek, as in English, horses yoked together are a metaphor for wedlock. Here the addressee’s companions in the flowering field are mares unyoked and set to graze by Aphrodite. Their liberty is that of the female who belongs to no one man and is sexually available to all.

For Sappho, woman’s sensuality blooms in the meadow, whereas male poets treat the presence of a desirable young woman in such surroundings as a blatant provocation. One of the earliest texts capitalizing upon these nuances in order to create a puzzle for its audience is the so-called “Cologne Epode” (PColon. inv. 7511.1–35 = fr. 196A West2) of the seventh-century BCE poet Archilochus. A native of the island of Paros, Archilochus was especially known in antiquity as the creator of virulent iambic, or “blame,” poetry. Instead of articulating the ideals of the hetaireia in a positive manner, iambic verse ridiculed outsiders, real or fictional, for acting in ways that offended collective values. Group solidarity was affirmed by scapegoating an Other, usually through scurrilous and obscene allegations. Archilochus’ fragments contain many coarse references, some quite bizarre: in one, a woman bending forward to fellate a man is compared to a Thracian or Phrygian slurping beer through a straw (fr. 42 West2).4 He was most notorious, however, for his attacks upon a fellow citizen, Lycambes, and his daughters, one of whom was named Neobule.5 Supposedly, Lycambes first promised Neobule to Archilochus in marriage, then broke the pledge, and Archilochus retaliated with a series of vicious attacks upon father and daughters that drove the latter to suicide. The Hellenistic epigrammatists Dioscorides and Meleager gallantly wrote protests on behalf of the dead girls, making them claim the allegations were untrue: “we never even saw Archilochus, we swear by gods and demigods, either in the streets or in the great precinct of Hera” (Anth. Pal. 7.351.7–8, cf. 7.352). This reference to a temple of Hera suggests that the Cologne Epode was set in its vicinity (Gentili 1988 [1985]: 185–7).

So much later tradition can tell us, but until 1974 we had very little idea of how Archilochus himself might have handled that scenario. With the publication of the new papyrus, we discovered that there, at least, he used the technique of first-person narrative to give his report a lively immediacy. The incomplete text begins with a young woman countering what was certainly a sexual proposition on the speaker’s part. He ought to curb his passion completely, she says, until she is of the proper age to marry. But if his desire is too pressing, he might consider taking as a substitute another girl from her household, “a beautiful and tender virgin who greatly longs for wedlock” (3–6). Like Nausicaa negotiating with Odysseus, the maiden is anxious to define her bargaining position: she welcomes the stranger’s hint at marriage but will not consent to premarital sex. By dangling the other girl, who she insists is both attractive and eligible, before his eyes, she is attempting to distract him from a worse option, rape.

“Daughter of Amphimedo,” the speaker formally replies, addressing her as the child of her deceased mother, “for young men there are many delights of the goddess apart from the divine thing [to theion chrêma]; one of these will suffice” (10–15). At our leisure, he goes on, you and I will discuss this at further length; meanwhile, I will obey your bidding. What is meant by “the divine thing”? Even ancient readers having the complete poem in front of them were perplexed by this circumlocution, which could refer either to marriage as a divinely sanctioned state or, as a Greek lexicographer glossed it, to sexual intercourse, so described because its pleasures are godlike (Van Sickle 1976: 137–43). If “the divine thing” is construed as marriage, he must be promising to wed her later provided she cooperates now; if sexual intercourse is meant, he is apparently proposing a substitute course of action.

Several cryptic, broken lines follow (14–16):

… up from below the cornice and beneath the gates …

don’t grudge me, sweetheart, for I will check at the grass-bearing

gardens …

As for the second girl, Neobule, he continues, let some other man take her. “She’s ripe twice over, her virginal bloom and grace (charis) are long gone, she’s mad for sex and can’t stop herself.” Popular beliefs about women’s insatiable nature would make such assertions credible. After the first taste of carnal pleasure, it was thought, they soon became addicted. Too much sexual activity, however, also caused women to age quickly. So Neobule’s desirability was short-lived, and, while still avid, she is now unappealing. To hell with her, says the speaker. With such a wife, I’ll be the laughing stock of the neighborhood. It’s you I want, for you’re not untrustworthy and treacherous. She’s just too hungry (oxyterê, literally “eager”) and makes too many “friends.” Jumping the gun in haste, he fears he produced, like the proverbial bitch, “a blind and premature litter.” Though he appears to accept blame for his part in the earlier fiasco, the canine allusion is one last dig at Neobule, since bitches were also proverbial for shamelessness.

Tirade over, the anecdote progresses to its logical finale (42–53):

Taking the girl, I laid her down

in the luxuriant flowers. Having wrapped her in my soft cloak,

supporting the nape of her neck with my elbow …

… she ceased … like a fawn …

and gently touched her breasts with my hands

… revealed her skin fresh with the approach of youth …

and stroking her beautiful body all over,

I loosed my vitality [menos], touching her blond hair.

What the narrator does may seem obvious on first reading, but it is not that clear, and divergent interpretations of the poem hinge upon how one reads these closing lines.

If the man who tells the story actually did have full intercourse with the daughter of a citizen, and one not yet of marriageable age at that, he would have also wronged her father Lycambes, who was the girl’s kyrios or guardian. Recall that Anchises in the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite does not do as the disguised Aphrodite bids him – respect her pretended virginity, turn her over to his parents for safekeeping, and contact her relatives to propose honorable wedlock – but instead rushes her into bed. Had she been telling the truth, he would have committed an act of hybris with grave political repercussions, for he is a Trojan prince and she was ostensibly the daughter of a king. Anchises thus shows himself the kind of rash fool impetuous enough to reveal the secret of his son’s origins later. The bedroom scene in the Hymn is clearly designed to give voyeuristic pleasure, so it is arguable that Archilochus’ account was also aimed at exciting his all-male audience with a racy description of plucking forbidden fruit.6 The narrator would then come across as a wily, smooth-talking rascal who achieves his immediate goal without quite making a permanent commitment – he has his way with the girl but postpones consideration of “the divine thing,” marriage, to some indefinite time. In the process, he also evens the score against his personal enemy Lycambes. Since Archilochus’ culture placed a high value on cleverness and verbal fluency and also understood revenge to be a man’s moral duty, such a twofold success might have been applauded by a Greek audience, no matter how much it offends our own sensibilities.7

An alternative interpretation of events, however, is equally possible, provided we allow for sexual double-entendre in the scrappy lines 14–16 translated above. “Cornice” and “gates” might be additional metaphors for the female sexual organs (in the context, it is hard to conceive of another explanation for their presence, as the narrator is surely not commenting on the temple architecture). What else could checking at “grass-bearing gardens” connote, then, but a promise to confine himself to the pubic hair, without entering the vagina? That would be one of the unspecified delights of the goddess available to him apart from the “divine thing,” full sexual intercourse. On that assumption, his addressing the girl with the matronymic (i.e., identifying her as her mother’s daughter, rather than using the father’s name for filiation, which was the ordinary procedure) is suggestive, because that was common practice for women speaking to each other privately, at least in the Hellenistic period (Skinner 1987; cf. Ogden 1996: 94–6).8 Confidential information about sexual techniques was reputedly the sort of thing women shared among themselves.9 In the absence of her mother, who is dead, the speaker tells the girl what she needs to know, doing so tactfully, through euphemism, as an older female friend would. When he looses his menos at the poem’s end, then, true to his word, he ejaculates outside her body, his penis touching her pubic hair. In so far as his act does not involve penetration, it may not have qualified as sex per se, even though orgasm was achieved. Counterintuitive as that argument may appear, we will shortly see why it can be made.

Which of these two scenarios is the correct one? Given the poem’s mutilated state, it is almost impossible to resolve that issue, and it is also conceivable that we were never meant to know. Archilochus, some have surmised, is playing games with his audience, leading it to anticipate a foreseeable outcome only to be taken by surprise. Having adopted a “feminine” persona to bargain with the girl he wants, the narrator reaches an apparent compromise with her, creates eager expectancy by his detailed description of amorous foreplay, then phrases the last words of his account so ambiguously that one cannot tell whether he has actually behaved as a “real” man in that situation would or should have done. In the end, then, the performer “eludes all the reactions that he has solicited in the course of performance” (Stehle 1997: 245, cf. Slings 1987: 50–1). If this is indeed the case, the witty representation of masculine prowess in the Cologne Epode is far more complex than corollary depictions of aggressive or victimized male gender identity in archaic lyric and elegy.

In sympotic love poetry, ordinary masculinity takes two forms. One is embodied in a “rhetoric of control,” in which the first-person speaker exercises his will over a second party. Whether he is carefully instructing a boy in the correct behavior for a trusty companion or castigating childish fickleness, the poetic ego speaking in this mode reflects his listeners’ conviction of their innate superiority to others in body, mind, and temper as members of a socially advantaged economic and gender class. An alternative construction of male identity, however, casts the speaking subject as the helpless target of repeated violence by Eros, whose blows he is incapable of resisting, or paradoxically transfers ascendancy in the relationship to the nominally submissive beloved. Each model inscribes the male subject into an asymmetrical grid of power relations: as a spokesman for the attitudes of his elite companions, he shares their rank, participates in their privileges, and derives prescriptive authority from them, but as a mortal inferior to the gods and susceptible to the sight of youthful beauty he is at the mercy of powerful extrinsic forces. This dual presentation of manhood incorporates the full range of tensions within symposium culture.

The elegiac verse of the Theognidean corpus is permeated with the rhetoric of control employed by the lover to dictate to his beloved. Normally the erastês addresses his companion like a preceptor, sometimes encouragingly, at other times sternly, always professing to have the boy’s best interests in mind. Here, for example, he applies strong psychological pressure in the guise of ethical training (1235–8):

Boy, master your feelings and listen to me. I will make a statement

neither unpersuasive nor unpleasing to your heart.

Make yourself grasp this word with your mind: it is not necessary

to do what is not in accordance with your desire.

With this guarantee of moral autonomy, the speaker paves the way for convincing the youth that he yields of his own free will. The related perils of treating a lover condescendingly, listening to false friends, and disregarding good advice are recurrent pedagogical themes in these elegies. At one point the speaker threatens a headstrong beloved with the fate of certain Greek cities of Asia Minor subdued by the Persians, presumably because they paid no heed to circumstances until it was too late (1103–4):

Arrogance [hybris] destroyed both Magnesia and Colophon

and Smyrna. Rest assured, Cyrnus, it will destroy you.

Finally, even as it pleads for the boy’s fidelity, another quatrain voices the suspicion and fear of the lower classes felt by those whose privileges are slowly being eroded (1238a–40):

Never send away your present friend and seek after another,

persuaded by the words of base-born men.

Often, you know, they will say groundless things against you to me,

and likewise against me to you. Take no notice of them.

In these last two couplets, anxiety about the personal conduct of the erômenos tellingly shades into concern about larger political realities.

A related dynamic is at work in poems where the speaker, rejected by an attractive boy or girl, retaliates with some kind of disparaging sexual innuendo. In the Cologne Epode, Neobule is figured as overripe, fly-bitten fruit. Fickle erômenoi in Theognis’ elegies are compared to birds of prey veering with every wind (1261–2) and horses indifferent to whoever rides them (1267–70). Anacreon too employs the flightiness associated with horses to insinuate that the girls he targets are incapable of behaving modestly. Listeners who can appreciate the clever implications of these metaphors are being invited to join the disappointed lover in mocking the object of ridicule. When an artist creates literary effects demanding such cultural sophistication on the part of the audience, he appeals to its sense of superiority: “models and metaphors for erotic relationships can function as part of a collective supremacist rhetoric involving the whole sympotic group” (Williamson 1998: 78). Poetry that provides an opportunity to participate vicariously in the experience of putting down a lower-status individual reaffirms elite privilege in the face of encroachment by other social orders. Fundamentally, then, it is a vehicle of tendentious political discourse.

When the male speaker is exerting dominance over another, his own bodily integrity is necessarily secure. In another poetic construction of masculinity, though, the boundaries of his selfhood lie exposed to Eros’ disruptive physical effects. Love as a kind of tangible affliction is a motif already implicit in epic narrative but developed to its fullest extent in archaic lyric. There it is identified as an elemental force of nature and characterized by epithets signifying its destructiveness (Thornton 1997: 11–47). Because the archaic Greeks regarded sensations of consciousness and feeling as corporeal and originating in specific organs, passion could be conceptualized as doing bodily harm in the manner of a crippling injury or a mental or physical illness (Cyrino 1995: 168). Masculinity is at stake when love invades the body’s perimeters, dissolving restraint and forcing its unwilling object to succumb to “womanish” longing. Calling upon this set of associations, Archilochus applies the epic language of combat death to the effects of love, which stabs him as an enemy would (fr. 193 West2):

… wretchedly I lie wrapped in desire,

faint, by the gods’ will pierced through the bones

with racking pains …

or simply overpowers him: “but, comrade, limb-loosening desire masters me” (fr. 196 West2). In both fragments the speaker suffers not only injury but also the shame of defeat by a stronger combatant. Similarly, Ibycus visualizes Eros rushing upon him like the north wind and forcibly pummeling his senses to the core (PMG 286), or casting him into the inescapable nets of Aphrodite (PMG 287). In what is perhaps the most imaginative use of “battering” imagery, Anacreon portrays Eros striking him like a blacksmith with a powerful sledgehammer and then plunging him into an icy winter torrent (PMG 413). Such images fuse excruciating physical pain with mental disorientation: in his distress, the speaker is unable to comprehend fully, much less articulate, what has befallen him (Cyrino 1995: 117). Loss of control over the rational self is complete.

When the lover is so consumed by his obsession, the hierarchical power positions of the pederastic relationship are reversed: it is the erômenos, not the erastês, who is now acknowledged as the dominant figure. Anacreon provides one revealing example (PMG 360):

Boy with the virginal glance,

I court you, but you pay no heed,

unaware that you drive

the chariot of my heart.

Corresponding descriptions of the lover as the suppliant or even the slave of the younger partner are found in Athenian philosophic discourse, while courtship scenes from Attic vase paintings of the late archaic and early classical periods show an older man urgently beseeching the favors of a younger one. This paradoxical exchange of functions de-emphasizes the subordination of the boy, indicating that his junior standing within the company is a transitional one and thereby distinguishing him from permanent inferiors, such as slaves and women (Golden 1984: 312–17). Adult members of the audience are meanwhile invited to participate imaginatively in the suffering of the poetic ego. Identifying with his despair and self-pity might afford maudlin pleasure at a particular stage of drunkenness, and reaffirming group solidarity through shared sentiment would also diffuse erotic rivalries threatening to create hostilities within the hetaireia. Although the conventional motif of the erastês as love’s puppet and fool may appear to invalidate the asymmetry assigning the partner of superior social status the dominant role in the relationship, this temporary and largely symbolic reversal could actually serve as an exception that proved the rule.

One of the commonest formulas in the surviving corpus of archaic Greek verse is the combination of “Eros … me … again [dêute]” forming the opening statement of a new poem. Far from learning from one bad experience, the lyric speaker constantly finds himself in the same predicament over and over again. Alcman, composing at Sparta in the second half of the seventh century BCE, is quoted as beginning a love song with “Eros again, by the will of Aphrodite sweetly flooding down, softens my heart” (PMG 59a). The fragment of Ibycus paraphrased above starts with the god “again looking upon me with his eyes meltingly from beneath dark eyelids” as he entangles the lover in Aphrodite’s nets. Anacreon employs the identical motif no fewer than five times: when golden-haired Eros hits him again with a purple ball (PMG 358); when he dives again, drunk with Eros, into the sea to cure his passion (PMG 376); when the hammer of Eros the blacksmith smites him again; when, in flight from Eros, he turns to Pythomander again (PMG 400); and when, combining “Eros” and “me” into the first-person verb ereô, he preposterously pronounces himself “again in love and not in love, mad and not mad” (PMG 428). Recurrent susceptibility to frustrated desire is yet another symptom of the lover’s fecklessness. Still, the ability to recognize such a tendency in himself implies a measure of emotive detachment: he “must necessarily possess some degree of objectivity and perspective on his current state” (Mace 1993: 338). This consideration intimates that the formula is being employed for self-referential or comic purposes, and the mocking ironies of Anacreon lend that notion plausibility. When the speaker speaks of himself as hammered and doused by Eros again or as attempting a suicidal leap to cure his passion again, it is obvious that a poetic conceit is being parodied. For this reason, too, the reader ought to suspect that the ideological construct of the male lover as victim of Eros is not meant to be taken as gravely as might be suggested by the extravagant language in which it is couched.

Against all such contrived laments over the harshness of love, we should set the elegist Mimnermus’ evocation of the alternative. Composing in Ionia on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean during the seventh century, Mimnermus was renowned for his two books of elegies. One, entitled Nanno, was reportedly dedicated to his mistress of that name, a girl flute-player. Hellenistic and Roman writers valued the sweetness and gentleness of his love poetry (Callim. Aet. 1.11–12; Prop. 1.9.9–10). The following elegy (Stob. 4.20.16 = fr. 1 West2), which may be complete in itself, shows why. In ten lines, densely permeated with Homeric vocabulary, Mimnermus voices a distinctly un-Homeric sentiment:

What is life, what is pleasure, without golden Aphrodite?

May I die when these things no longer matter:

secret intercourse and soothing gifts and bed,

which are flowers of youth to be plucked

by men and women. But when painful old age comes on one,

which makes a man both shameful and sordid,

evil cares always oppress his heart,

nor does he enjoy beholding the light of the sun;

instead he is hateful to boys, contemptible to women.

So bitter a thing the god made old age.

Plutarch affirms that the art of poetry is the same whether practiced by an Anacreon or a Sappho (De mul. vir. 243b). In composing for an audience of women, Sappho treats the same erotic themes as her male counterparts and employs familiar literary formulas and imagery in equivalent ways. Like them, she envisions sexual desire as a violent natural phenomenon (“and Eros shook my heart like a wind in the mountains falling upon oaks,” fr. 47 V). Desire is also, familiarly enough, “limb-loosening,” and, in a straightforward application of the dêute formula, it again makes her tremble – although in the next line it is further described, strangely, as a “bittersweet uncontrollable crawling thing” (fr. 130 V). Among all the lyric poets, finally, Sappho provides the most clinical description of erotic pathology, characterizing the effect of glimpsing the beloved as a progressive breakdown of one bodily faculty after another, verging at last upon death (fr. 31 V).

Despite these and other similarities, however, Sappho’s concept of female sexual experience does not resemble paradigms of sexuality in male-authored poetry: contemporary feminist critics trace out a different configuration of eroticism in her lyrics. In contrast to the male erastês’ adversarial relationships with his love object and with the god afflicting him, her dealings with both mortals and divinities seem mutually rewarding. Most obviously, her speaker does not attempt to impose her will upon the person she loves, but instead, through engaging appeals, tries to elicit a corresponding response from her (Stehle [Stigers] 1981; Skinner 1993: 133–4; Greene 1996 [1994], 2002).10 Often, the poems are addressed to another desiring person whose feelings are given lyric expression through the speaker’s empathy. Williamson explains this as a “circulation” of desire in which the difference between “I” and “you” as subject and object is elided (1995: 128–31, 1996: 253–63). Lastly, Sappho’s personal contacts with Aphrodite are warm and intimate, and poems 2 and 96 show the goddess participating actively in the celebrations of the Sapphic circle. Elsewhere in the sympotic tradition, as well as in Homer and Hesiod, Aphrodite’s gifts are valued, but she herself is a dangerous entity. Only in Sappho’s lyrics does she enjoy a comfortable companionship with mortals.

In the “Ode to Aphrodite,” Sappho’s only wholly surviving poem (fr. 1 V), Aphrodite’s behavior resembles, and may well be modeled upon, Athena’s assistance to her favorite warriors in Homer (Winkler 1990: 166–76). Divinity and mortal share a moment of rapport, while the self-conscious use of dêute is taken to amusing lengths. The speaker begins by appealing to Aphrodite’s mercy and reminding her of a previous epiphany. In response to Sappho’s cries on that occasion, Aphrodite had descended in her sparrow-drawn chariot and requested a briefing (13–24):

… and you, blessed lady,

with a smile on your immortal countenance,

asked what I suffered again [dêute] and why

I called on you again [dêute],

and what I most wished to happen to me

in my maddened heart. “Whom do I persuade again [dêute]

[…] into your friendship? Who, Sappho,

wrongs you?

For if she flees, soon she will pursue,

if she does not receive gifts, she will give them,

if she does not love, soon she will love,

even unwilling.” (emphasis added)

In addressing the speaker as “Sappho,” Aphrodite engages her not as a repeatedly frustrated lover but as a poet who uses the dêute formula, implying that her repertoire “includes a regular litany of love complaints of the form ‘Eros … me … again’” (Mace 1993: 359–61). The poem thus becomes a programmatic “signature piece” neatly reprising the singer’s characteristic themes. When Aphrodite is asked to return, in the concluding stanza, to accomplish Sappho’s present objective and to become her symmachos (“fellow-fighter”), she is being enlisted as both helper in love and creative ally, an equivalent of the Muse. In this ode, consequently, homoerotic desire is a stimulus to artistic invention (Skinner 2002: 66–9). This is atypical, for elsewhere in the archaic literary tradition song may indeed be a balm and consolation for love’s suffering, but the pangs of desire, an unwanted intrusion on male self-possession, cannot generate anything as constructive as art.

We have virtually no textual evidence for archaic social conditions on Sappho’s native island of Lesbos, situated in the eastern Mediterranean just off the coast of modern Turkey. Elsewhere in mainstream Greek culture a male-centered, patriarchal gender ideology was so entrenched that it is not easy to imagine a milieu that could give rise to this seemingly unorthodox, female-oriented construction of sexuality. As it tenders near-contemporary iconographic evidence for women’s private dining, however, a recent archaeological discovery, the “Polyxena Sarcophagus,” helps us visualize Sappho performing in a similar kind of setting.11 Made by Greek artists for Persian patrons, the sarcophagus was excavated in 1994 from a tumulus in the northern Troad, in the same geographical region as Lesbos, which would in fact have been the closest major site of Greek occupation. It is late archaic in date and may therefore have been carved between fifty and seventy-five years after Sappho’s death, since she is conventionally assigned to the end of the seventh and beginning of the sixth centuries BCE.

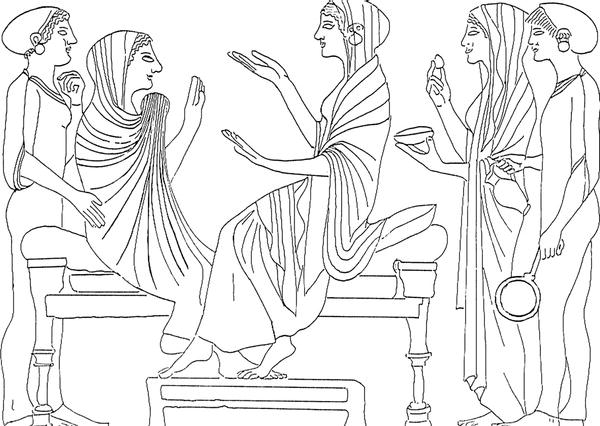

Two faces of the sarcophagus deal with the sacrifice of Priam’s daughter Polyxena. On the principal long side, four men participate in her killing, while six women look on making gestures of grief; on the short side to the right, Hecuba, her mother, mourns with two companions. The second long side depicts a funerary celebration, dominated by a seated woman in the center, who may represent the deceased. Four women surround her and two bring gifts to her. At the right of the same scene, two female musicians play while four armed warriors dance; they are watched, in turn, by four additional women. Sevinç, the discoverer of the sarcophagus, remarks upon the high visibility of women in the scene: “the men are relegated to the status of performers, whose movements follow the rhythms made by female musicians” (1996: 262).

It is the picture on the fourth side that is most germane to the present discussion. That it is pendant to the funerary celebration is indicated by the parallel relationship of the Hecuba scene to that of Polyxena’s sacrifice. Five women are grouped in a convivial situation (fig. 2.2). One, at the far left, raises one hand toward her face while touching the back of a second woman with the other. She, in turn, is seated upon a dining-couch (klinê), sharing it with a third woman, the most prominent of the group. The two are having an animated conversation: the woman on the right makes an explanatory motion, while the other, raising her mantle and gesturing with the palm of her hand, expresses delighted astonishment.12 To their right, two women look on: one holds an egg in her right hand and a dish in her left; the other holds a pitcher in her right hand, a mirror in her left. The egg and mirror connect this scene to the previous one of the funerary meal, where a bowl of eggs and a mirror are presented to the central figure. Mirrors are characteristic attributes of women in a domestic setting and eggs, a symbol of immortality, are appropriate grave offerings (Sevinç 1996: 262).13 The symposium scene may therefore be a continuation of the depiction of the funerary banquet, or it might reflect a prior moment in the earthly existence of the deceased. In either case, the sarcophagus, which has no contemporary parallels in Greek art, affords evidence of women’s sympotic activities from a geographical locale and a time period not far removed from those of Sappho. In such a private, hospitable environment, desire and music might well accompany each other as parallel and interrelated expressions of female subjectivity.

Fig. 2.2 Polyxena sarcophagus,c.525–500BCE. Short side at right of funerary celebration: women at symposium. Source: Drawing by Dr Nurten Sevinç. Originally published inStudia Troica 6 (1996), p. 261. Reproduced by permission of Dr. C. Brian Rose on behalf of the Troy Project.

Until now we have been speaking of the symposium as though it was all of a piece, but it actually was divided into three parts, according to classical Athenian sources. First came the dinner, consisting of bread, the staple, and what was put atop it: cheese, oil, vegetables, and, as a special delicacy, fish, for meat was consumed only on sacrificial occasions (Davidson 1997: 3–35). Food is central to depictions of symposia in Attic comedy, but archaic elegy and lyric instead concentrate on rituals of drinking (Wilkins 2000: 203). Those activities were conducted separately; only after the meal was concluded did the communal drinking, the symposium proper, begin. Since it had a high alcohol content, wine was tempered with water in a mixing bowl (krater), and scholars calculate that the resulting mixture was equal in potency to modern beer. Guests were served the same quantity in order. At a restrained, temperate symposium, the krater was filled no more than three times, enough to enliven conversation and leave guests feeling mellow; further refills, warns the god Dionysos in a comic fragment, successively lead to violence, shouting, routs, black eyes, summonses to court, vomiting, madness, and throwing furniture around (Eub. ap. Ath. 2.36b–c). If drinking continued, the symposium was likely to end in a kômos, a noisy procession through the streets to demonstrate group solidarity. As Plato tells it, the decorous philosophic gathering at Agathon’s house is interrupted, first by an inebriated Alcibiades and a few of his guests, and then by a second group of revelers who find the door open, stumble in, and make themselves at home carousing (Symp. 212c–e, 223b). If Plato is not distorting the historical picture, the closest analogue to Athenian streets after dark might be a university district after a Big Game victory. In his dialogues, though, drunkenness carries a great deal of symbolic weight, so we should not treat the Symposium as sociological evidence for the frequency of loud public disturbances.

Other kinds of men’s gatherings, while designed, like the symposium, to foster comradeship and group loyalty, were more closely bound up with the military responsibilities of male citizens. Most noteworthy among these was the Dorian habit of communal dining. The inhabitants of Crete, an island in the central Aegean, and those of Sparta, whose territory lay at the southern tip of mainland Greece, both spoke Doric, a Greek dialect, and preserved similar archaic institutions, attributed in each case to a mythic lawgiver, Minos of Crete and Lycurgus of Sparta.14 Spartan men ate in syssitia, eating clubs composed of fifteen members each. All members were expected to contribute a fixed amount of food and drink each month to the common mess, although the wealthier might provide more than was required. If a man became too poor to contribute his monthly ration, he could not exercise his rights of citizenship (Arist. Pol. 1271a.29–32, 1272a.12–16). Food was nutritious but not plentiful; wine was served, but drunkenness was branded as shameful. The dining arrangements of the Cretans were similar: adult males partook of vegetables, meat, and well-watered wine in the andreion, “men’s house.” Drunkenness, Plato tells us, was there prohibited by law (Min. 320a). Unlike at Sparta, however, meals were subsidized by the state. Aristotle, to whom we owe the latter fact, also states that the custom of dining in common originated with the Cretans and was then brought to Sparta (Pol. 1271a.1–3), a belief shared by many other classical authors.

Xenophon, who spent twenty years among the Spartans and observed their institutions at first hand, praises the moderation and temperance encouraged by communal meals, where the mix of ages ensured that elders would restrain their juniors from overindulgence (Lac. 5.4–7). In the Laws, however, Plato’s spokesman, a stranger from Athens, shocks his two walking companions, Cleinias, a Cretan, and the Spartan Megillus, with his declaration that their zero-tolerance policy against drunkenness is an impediment to rational self-control, since it does not allow for practice in overcoming temptation (647a–650b).15 More crucial to our inquiry, he identifies the gymnasium and the common meal as institutions that promote physical relations between members of the same sex (nothing is said about private symposia), and notes that Crete and Sparta are jointly held responsible for introducing the custom of pederasty to Greece. This passage (636b–d), which, as we saw earlier, has even found its way into a constitutional legal brief, is foundational to the scholarly claim that pederasty has a basis in initiation rites. The ethical issues raised here furthermore suggest that approaching Greek homoeroticism as a collective expression of social behavior is more illuminating than regarding it as the product of individual inclination, motivated by pleasure – our own usual context for erotic acts.

When the Athenian Stranger asks for examples of Dorian rituals that educate youth in courage and self-restraint, Megillus replies that communal dining and gymnastic exercises encourage both virtues. The Athenian objects. Such institutions are the breeding-ground for civil strife, he declares, and, what is more,

the very antiquity of these practices seems to have corrupted the natural pleasures of sex, which are common to man and beast. For these perversions, your two states may well be the first to be blamed, as well as any others that make a particular point of gymnastic exercises. Circumstances may make you treat this subject either light-heartedly or seriously; in either case you ought to bear in mind that when male and female come together in order to have a child, the pleasure they experience seems to arise entirely naturally. But homosexual intercourse and lesbianism seem to be unnatural crimes of the first rank, and are committed because men and women cannot control their desire for pleasure. It is the Cretans we all hold to blame for making up the story of Ganymede: they were so firmly convinced that their laws came from Zeus that they saddled him with this fable, in order to have a divine “precedent” when enjoying that particular pleasure.16

Let us put aside for the moment the question of what the Athenian Stranger means by describing same-sex copulation as “unnatural” (para physin), in contrast to heterosexual relations; we will take up that issue when we discuss the development of a philosophical discourse on sex and marriage during the Hellenistic period. Here we are interested in the Stranger’s claims about its origins.17 We must bear in mind that he is talking about pederasty as an institutionalized social activity, for it was the overt recognition of pederasty as a legitimate social practice, within certain parameters, that set the Greeks apart from other peoples (Dover 1988: 115). The Athenian makes three assertions: the educational system of Crete and Sparta, with its emphasis on all-male dining and gymnastic exercise, promotes homoerotic sex; the antiquity of that system has given rise to the belief that pederasty originated in those two states; the Cretans are further thought to have invented the myth of Ganymede’s abduction as a justification for the custom, which implies that they themselves saw a need to justify it.

Other ancient evidence seems to support the connection Plato is drawing between the upbringing of boys, as carried out in Dorian states, and pederasty. We can begin by summarizing what three more writers, Xenophon, Aristotle, and Plutarch, have to say about the agôgê or age-based educational system of archaic and classical Sparta. The Spartans felt themselves constantly exposed to threats of an uprising posed by former inhabitants of the surrounding territory whom they had conquered and reduced to slavery. Therefore their whole social organization had the single objective of producing first-rate combat troops, and the agôgê was essential to that purpose.

Over a period of thirteen years, young citizen males passed through three stages of instruction defined by age, acquiring more rights and responsibilities in each. Socialization (paideia) began at seven, when boys were removed from the home and placed in a band of age mates (agela, literally “herd”). From that point on they ate, slept, and were schooled in common. The boys were trained in song and choral dance, but lessons in reading and writing were kept to a minimum. Starting at twelve, they cropped their hair, wore no tunics and were given just a single cloak each year. In athletics and mock fighting, they competed strenuously with each other and against other agelai, enduring cold, hunger, and physical hardships, including severe whippings. At twenty, after gaining combat experience as reservists or guerrilla fighters, youths graduated from the agôgê, were admitted to a syssition, and became entitled to marry. Yet they were still required to bunk with their messmates: conjugal visits to the bride’s home were infrequent and clandestine.18 When they reached thirty, they could finally leave the barracks and live in their own households, but they continued to dine with their eating group into old age. This arduous program of socialization was designed to instill conformity, obedience, courage, and stamina – traits highly valued in Spartan society.

Xenophon locates pederasty firmly within the context of the state-sanctioned instructional system, remarking, by way of introduction, that it is “related in some way to paideia” (Lac. 2.12). The lawgiver Lycurgus, he tells us, approved of a decent man attempting to befriend and associate with a boy whose soul he admired; this he deemed “the noblest form of education” (kallistên paideian). The infamy attached to carnal intercourse ensured that physical relations with the beloved were avoided no less than incest (2.13). Xenophon fears, though, that people will doubt his word because the laws in many poleis do not forbid sex with boys. Although Aristotle too appears to deny that the Spartans approve of intercourse between males (tên pros tous arrenas sunousian), in contrast to the Celts who do, he is probably speaking there of two adult men, as the statement occurs in a discussion of men’s dealings with their wives (Pol. 1269b.26–27).

Plutarch – writing more than four centuries after Xenophon, but having access to many earlier sources now lost – says nothing in his Life of Lycurgus, which contains his fullest treatment of the agôgê, about whether or not pederastic relationships were physically consummated. He does, however, provide many other particulars about such involvements not found in Xenophon’s account. Boys began to receive the attentions of erastai from among the young men of good reputation when they were twelve (17.2). Individuals under thirty, the age of full maturity, did not go to the marketplace but instead had their daily needs supplied by kinsfolk and lovers (25.1), which may imply that pederastic associations at Sparta were prolonged well past the age at which they customarily ended in other Greek states. Although discipline was communal, and elder men as a group had the right to chastise any younger male, the erastês was expected to act as a surrogate father, for he himself was held responsible if the boy behaved poorly (18.4). Cartledge identifies this as an instance of “displaced fathering,” a phenomenon found in many other cultures (1981a: 22).

Parallels with Spartan usages can flesh out information about the education of young men in fourth-century BCE Crete. Our informant is Ephorus, who dealt with the Cretan constitution in the fourth book of his lost Histories, probably composed soon after Plato’s death in 347 (Morrow 1993 [1960]: 21–5). Ephorus’ account of Cretan paideia is excerpted by the early imperial Roman geographer Strabo in considerable detail (10.4.20). In Crete, too, we are told, youths were classified into age-grades. Prepubescent sons were taken to the men’s halls, where they waited on their fathers and the other adult diners; when they themselves ate, they sat together on the ground, not at table.19 Both in summer and winter they only wore scant shabby cloaks, like their Spartan counterparts. In Crete the classroom curriculum also consisted of elementary reading and writing, together with musical instruction. At seventeen, the adolescent joined an agela where he participated in organized activities such as hunting, athletics, and mock combat. Either at this time or upon leaving the agela at twenty, he was given the right to attend the public gymnasium. Marriage, finally, was both compulsory and age-related: all youths leaving the agela were ceremonially married at the same time, although the groom did not take the bride home right away but waited until she was old enough to manage a household. This is because the legal age of marriage for Cretan girls was twelve – unlike Sparta, where the Lycurgan code prescribed that girls marry in their late teens, so they would be mature enough to bear healthy children.

With some minor variations, then, the experience of passing from boyhood to adulthood in Sparta and Crete seems comparable: it was formally structured by age-group, it emphasized physical education and the development of combat skills, and its progress was marked by obvious rites of transition, like the cutting of hair or marriage en masse. One custom of maturation, however, is peculiar to Crete – at least we have no evidence that it ever happened anywhere else, and Strabo himself thinks it strange (idion). It involves the ritual abduction of the boy and is described as follows (10.4.21):

The lover announces to the boy’s relatives three or more days in advance that he is going to make the abduction. For them to hide the boy or not let him walk along the appointed road is deeply disgraceful, because they would be admitting that he does not deserve to get such a lover. When the parties come together, if the abductor is the boy’s equal or superior in rank and other matters, those kindred rush at and grapple with him, but only as a token gesture to satisfy custom; then they gladly turn the boy over to him to lead off.

A perfunctory chase follows, which ends at the door of the lover’s andreion. The pair then goes off to a remote area in the wilderness, where, accompanied by friends, they remain for two months, feasting and hunting. When they return to the city,

the boy is let go after receiving as gifts a military outfit, an ox, and a drinking cup20 [these are the gifts prescribed by law] and other things so numerous and costly that his kinfolk chip in because of the sum of expenses. The boy sacrifices the ox to Zeus and entertains those who came back with him, and then he gives an account of his relations with his lover, whether he was satisfied with them or not. The law permits him this so that, if any force was brought to bear upon him in the course of the abduction, he is empowered to avenge himself at this point and get rid of the offender. For those who are attractive to look at and of prominent ancestry it is disgraceful not to obtain lovers, since the assumption is that they suffer this because of their character. But the “ones who stand beside” [parastathentes], for so they call the abductees, receive distinction, because in both the choruses and the races they have the most honorable positions, and they are permitted to dress differently from their peers in the outfit they were given by their lovers, and not only then but after becoming adults they wear conspicuous clothing to indicate that each was “renowned” [kleinos], for they call the beloved kleinos and the lover philêtôr.

Although the act of boy-abduction, which probably happened at puberty, has obvious equivalents in myth – Ganymede was carried off by Zeus, Pelops by Poseidon, and Chrysippus by Laius, the father of Oedipus – its only historical Greek analogue is the well-known staged capture of the Spartan bride, which Plutarch also refers to as a harpagê or abduction (Lyc. 15.3). The parallels are indeed striking, for the Spartan ceremony must also have involved a token show of force. Both the kidnapping of the boy and the mock-seizure of the bride would allow a prospective lover or groom to display his physical skills and mental and moral capacities to the relatives of his intended, so proving himself worthy to ally with them – a vital consideration in a warrior society (Patzer 1982: 82–3).21

Yet, according to several scholars, the analogy between the two rites ought not to be pressed too far. Bride-abduction was a symbolic token of the groom’s desire, which the Lycurgean code promoted in the belief that passionate intercourse would produce more vigorous infants. Institutionalized pederasty, on the other hand, was a survival of a prehistoric procedure of ritual initiation for young males.22 Copulation with boys, according to this theory, had the same function as in rituals of maturation reported for certain modern tribal cultures of the southwestern Pacific region. There anthropologists have amply documented the existence of a belief that semen is the physical medium through which adult masculinity is transmitted. The sex-segregated warrior communities of Melanesia are worried about the proper gender development of youths, who may have been subjected to dangerous feminine influence during childhood contact with the mother.23 In order to become men, boys must consequently be inseminated, whether through oral or anal genital contact or by having seminal fluid applied to incisions.24 Bremmer argues that this same notion, if not universal among pre-literate cultures, was a common assumption of Indo-European peoples (1980: 290). Greek ritual pederasty was therefore a means of socialization to which the lover’s sexual gratification was purely incidental.

Because it was rooted in the earliest historical period of proto-Greek civilization, only the conservative, archaizing societies of Crete and Sparta are thought to have preserved pederasty in what was closest to its original form. Apart from historical reports of the custom in those two areas, traces of its formerly widespread existence are claimed to subsist in a broad array of myths, set in various geographical areas of Greece, that account for the origin of homosexuality in a given locale. The antiquity of so many of these narratives, especially those concerned with pupils and their divine or human teachers (Apollo and Hyacinthus, Poseidon and Pelops, Hylas and Heracles, to name three), suggests that rites of initiation involving pederasty were numerous in the pre-polis era (Sergent 1986: 259–69).

Initiatory elements certainly seem to feature in the Cretan custom of abduction. It is demonstrably a “rite of passage” involving separation from a previous existence, spending of a certain period of time in a liminal state, and final reincorporation into the community, at which point the subject’s new status is acknowledged (Van Gennep 1961: 21, 65–115). Carrying off the boy to the lover’s andreion imposes a break with his past life, and the sojourn in the wild, where he receives instruction in hunting, a manly skill, can be regarded as a “betwixt-and-between” phase of existence. After coming back to civilization, the boy is given gifts that correspond to his altered circumstances: the warrior’s clothing marks his new responsibilities as a defender of society; the ox sacrificed to Zeus, whose meat is shared with companions, is an emblem of his future religious duties as head of a household; and the wine cup is a token of his admission to the men’s feasts, since boys’ consumption of wine, in Crete as generally throughout Greece, was strictly monitored (Sergent 1986: 16–20).25 Ephorus’ account of this custom, which was already almost obsolete in his day, is therefore the primary text most cited as evidence by proponents of the initiatory hypothesis.

In other parts of the Greek world, pederastic courtship, according to the same theory, gradually lost its initiatory purpose and became an activity engaged in by the aristocracy for its own sake, with youthful beauty the main attraction and the lover’s eventual gratification its objective. Yet it never entirely lost its association with training in adult citizenship, which explains why instruction in aretê, “manly virtue,” remained such a prominent aspect of the ideal relationship of lover and beloved in classical Athens (Patzer 1982: 111–14). Similarly, the role in the initiatory process once played by all-male dining clubs is reflected in the attention still given to pederasty in poetry created for the archaic and classical symposium, the gathering that eventually took the place of the syssition or andreion (Bremmer 1990: 137).

Some archaeological discoveries have been interpreted as supporting this hypothesis of origins. The Chieftain Cup, a carved Minoan drinking vessel found at Ayia Triada in Crete and dated to approximately 1550–1450 BCE, pictures two youthful male figures of unequal height, armed with weapons, facing each other. Because of their distinct and unusual hair styles, which in Minoan art seem to indicate differences in age and status, the cup is thought to illustrate the actual rite described by Ephorus: supposedly, it shows the philêtôr, the taller figure, handing over the three designated gifts to the kleinos. The rural sanctuary of Hermes and Aphrodite at Kato Syme yielded two dedications that may forge continuity of practice between Minoan Crete and the Greek archaic age. A bronze figurine of the eighth century BCE depicts two helmeted nude males standing side by side holding hands; they are again of different heights, and each has an erect penis. In a bronze relief plaque from the middle or late seventh century now in the Louvre, an adult bearded man faces and grasps the arm of a younger man carrying a wild goat, possibly an allusion to the two months the boy and his captor spent hunting. In the absence of any written records, these images are difficult to interpret; if they have been explained correctly, however, they seem to indicate that boy-abduction was a Minoan ritual taken over by later Dorian invaders (Koehl 1986: 107–8 and plate VIIb). Though the Minoans’ ethnic affiliations are mysterious, many scholars believe they originally came from Anatolia (modern Turkey), while, at the height of their prosperity around 1700 BCE, they maintained strong cultural ties with the Near East and Egypt. Tracing the practice of initiatory pederasty back to Minoan Crete thus creates a problem for those who would define it as an Indo-European survival.

Inscriptional evidence has also been brought to bear on the problem. Found in a house at Phaistos, a storage jar from the Geometric period (750–30 BCE) bears an incised graffito that identifies it as belonging to “Erpetidamus, son of a lover of boys [paidop(h)ilas].”26 Along with the bronze votives mentioned above, this is the earliest support for the argument that pederasty was institutionalized in the Greek world before 700. Mid-sixth-century graffiti from the Spartan colony of Thera, an island near Crete, praise the beauty and dancing skills of boys, and some mention sexual acts. The inscriptions were found on a rock wall and other locations in the vicinity of both a later Hellenistic gymnasium and a temple of Apollo Carneius, who at Sparta was one of two divinities most concerned with the upbringing of the young.27 When, in IG XII 3.537, we read that “by [Apollo] Delphinios, here Crimon mounted a boy, the brother of Bathycles,” the writer’s appeal to the god to bear witness may indicate that these are “ritual inscriptions, designed to celebrate the completion of initiation ceremonies” (Cantarella 1992: 7; cf. Graf 1979: 13). Still, they could just as easily be secular boasts and taunts (Dover 1978: 122–3; 1988: 125–6), and some considerations strengthen that possibility. The verb oiphein used in the above graffito as well as others is a Doric dialect expression for “have intercourse,” blunt though not offensive (Bain 1991: 73–4). Yet we would expect a sacral pronouncement to resort to euphemism when speaking of the act. Again, one other inscription (IG XII 3.540) designates a Crimon, probably the same person, as “first in the Konialos,” evidently the name of an obscene dance associated with an ithyphallic divinity (Scanlon 2002: 85–6).28 Finally, and most problematic for the “religious inscription” reading, there was a firm Greek taboo against having sex in a sacred place, so it is very unlikely that ceremonial intercourse would occur, as the graffiti attest, within Apollo’s very precinct.

Despite the explanatory appeal of the initiatory hypothesis and the supposed existence of much corroboratory evidence, vigorous objections to it have been raised by K. J. Dover (1988: 115–34). Dover questions whether the beliefs of geographically remote contemporary peoples can cast light upon archaic Greek cultural systems. Among other objections, he denies the supposed universality of primitive faith in the “masculinizing” power of semen and in ritualized homosexuality as an initiatory practice.29 He also points to the complete absence of any recognition of homosexuality in Homer, Hesiod, Archilochus, and even in Tyrtaeus, a Spartan war poet (last half of the eighth century BCE) who, if anyone, might have had something to say about “the erastês setting an example of valour to his erômenos” (1988: 131). Consequently, he proposes that homosexuality, both male and female, was, as he puts it, brought “out of the closet” around 600 BCE by “Greek poets, artists, and people in general” – that is, that it was rendered acceptable and popularized by opinion-makers of the time. Myths, which still circulated orally, were reinterpreted in the telling to conform with new audience expectations: the rape of Ganymede, for example, was now attributed to Zeus rather than the Olympians as a collective group and given a sexual motive previously lacking.30 What we observe in the late archaic age is, to summarize Dover’s position, the invention of romantic pederasty – its introduction into Greek discourses on erôs as an acceptable pattern of social conduct. As a recognized institution it had previously been nonexistent, despite the likelihood that individual private acts of sex with boys would have taken place often enough.

The silence of epic is Dover’s best argument. True, there may be reasons for that omission other than absence of the corresponding reality. In non-literate Homeric society, epic poetry recited on public occasions served as an educational medium, encoding social norms in easily remembered narrative form and thereby transmitting values from one generation to the next. Because its purpose was communally oriented, it might not have dealt with all sides of human life but instead concentrated upon relationships that reproduce social institutions and ensure family survival. That may be why Homer and Hesiod are exclusively concerned with sexuality in the context of marriage, procreation, and inheritance of an estate, as well as with the negative social consequences of deviant heterosexuality. Other kinds of sexual activity could have been engaged in covertly or openly with their existence simply ignored by early poets. Nevertheless, the want of references, even cautionary or derogatory ones, to any kind of same-sex relationship in the Hesiodic corpus or in Archilochus, who is quite blunt about sex with women, does seem peculiar if ritual pederasty was as much an element of maturation throughout the prehistoric Greek world as the initiatory hypothesis requires it to be.

Assuming, for the sake of discussion, that Dover is right, what cultural factors would have awakened interest in a type of sexual behavior of which literature had previously made no mention? Dover himself refuses to speculate, but historians swayed by his overall argument have tried to fill the explanatory gap by extrapolating from known phenomena. Scanlon, for example, hypothesizes a gradual escalation of interest in both athletics and pederasty from the eighth to the sixth centuries, spurred on by “heightened social competition for status” (2002: 68). Aesthetic admiration for the physical form of the boyish contestant, coupled with the spread of athletic nudity from Sparta to other communities, would account for a “likely cooperative evolution between the gymnasium and the popular acceptance of pederasty” (2002: 212). But that seems a secondary consequence rather than a root cause.