3

Late Archaic Athens: More than Meets the Eye

Literature is not our only major source of information for ancient sexual ideology.1 During the “Golden Age” of Attic pottery, from approximately 600 to 400 BCE, workshops at Athens, the hub of the Greek ceramic industry, manufactured fine earthenware for household and religious use. Much of this pottery was decorated with scenes drawn from mythology and the daily life of men and women.2 The heyday of the craft spanned the era of Athens’s hegemony over the Greek world – beginning with Solon’s first steps toward the establishment of a democratic system of government in the archaic period, extending through the rule of the Pisistratid dynasty, the Persian Wars, the formation of the Delian League and the consolidation of the Athenian empire during the mid-fifth century, and the brutal Peloponnesian War with Sparta, finally ending with Athens’s defeat in 404, which resulted in the breakup of its empire. Judging from the degree of craftsmanship, which ranges from exquisite to coarse and shoddy, even the relatively poor could afford painted ware, although ordinary people probably owned only a few display vases.3 By any definition, though, this was a popular medium, a fact that justifies treating Attic vase painting as a foundation for wide-ranging discussions of attitudes and concepts shared by the general public to which it appealed.

In Greek Homosexuality (1978), K. J. Dover assembled a large compendium of erotic scenes on vases to demonstrate certain aspects of the Athenian homosexual ethos, including ideals of youthful beauty, gestures of seduction, favored positions and, by omission, taboo subjects. Subsequently Eva C. Keuls (1985) drew on the same corpus of materials as evidence for her contentions about the treatment of women in Athenian society. Since then, studies of Attic pottery have been at the forefront of work on ancient sexuality. Approaches are often chronologically oriented, with changes in subject matter analyzed as indications of alterations in the preferences, and arguably the mentality, of purchasers (Shapiro 1981, 1992; Sutton 1992; Osborne 1996). For example, scenes of courtship and lovemaking, whether merely suggestive or explicitly sexual, were quite popular during the period 575–450 BCE but are rarely found thereafter. Meanwhile, from the middle of the fifth century onward, representations of respectable women at leisure increase considerably. Determining the cause of such shifts in taste would help to fill in the background needed to interpret the ideological debate about sexual ethics reflected in Athenian texts of the later fifth and fourth centuries.

When working with this body of evidence, however, we must use caution. At first glance it may seem that scenes on vases give us photographic access to life as it was really lived, but that impression would be wrong. For one thing, figures are stylized rather than realistically drawn, and a rich vocabulary of symbolic gestures is employed to convey meaning. Much of this code of pictorial representation, or iconography, is still not fully deciphered.4 Second, content was affected by alterations in technology, most notably the switch from the black-figure to the red-figure method of vase painting around 525 BCE. The first technique employed figures painted in black upon a red clay background, with bright red and white as secondary colors; details such as patterns on clothing were incised. In the second technique, conversely, figures were outlined on the unfired clay pot, interior details painted in, and the background then covered with a glossy grey slip that turned black during the firing process. Osborne draws a critical distinction between the objectives of each style: black-figure emphasizes action and setting, while red-figure focuses upon the spatial presence and bodies of individuals (1998: 134–9). Although both techniques are used for erotica, the tone of the representations differs: black-figure portrayals of sex tend toward the comic or boisterously obscene, while red-figure, with its greater intensity, attempts to involve the viewer psychologically in the proceedings.

We must also allow for the surroundings in which erotic scenes, especially those with graphic sexual content, were meant to be viewed. Distinct kinds of vases were employed for given purposes, with function often determining decoration (Webster 1972: 98–104): thus figures of women at the public fountain appear on hydriai, which were used to fetch water. Sexual scenes are restricted to equipment for the symposium, and symposia were extraordinary occasions on which, under the sway of Aphrodite and the god of wine, Dionysos, participants could engage in activities not normally countenanced. Use of tableware decorated with images of such activities would set the gathering apart from an everyday dining experience. Hence these vases and cups were designed for proper viewing by specific individuals under specific and controlled circumstances. We have to distinguish between intended and unintended audiences, keeping in mind that not everyone who saw the picture of lovemaking on the bottom of the drinking cup would respond to it in precisely the same way. It may be advisable to distance ourselves from these images occasionally by putting ourselves in the place of the female slave who cleaned the tables and washed the dishes the next morning.

Out of Etruria

Speculation about the purpose served by such erotic representations is quite heated. Were they pornographic, meant to arouse the viewer sexually, or instead a stimulus to imaginative fantasy (Kilmer 1993: 199–215)? Looking past their literal content, should we regard ancient sexual images as apotropaic (evil-averting) measures or as a mode of symbolic discourse? Did they merely reflect the personal outlook of their consumers or actually mold it (Sutton 1992: 32–4)? Their numbers are small: out of tens of thousands of surviving vases, only about 150 show figures actually engaged in sex, while about two thousand more deal with erotic themes in a more restrained manner.5 Provenance creates a tremendous problem, for the overwhelming majority of those vases were not found in Athens but recovered from the graves of wealthy Etruscans in central and southern Italy. The Etruscans were great admirers and collectors of Greek art who imported vases from Attica along with other luxury artifacts. Aristocratic Etruscan women were publicly more visible than their Greek counterparts, and in their own art the Etruscans did not hesitate to express affection between husbands and wives – cultural factors known to the Greeks, who gave them a sinister interpretation.6 Some scholars have claimed, then, that explicitly erotic scenes were created only for the export market and reflect Etruscan, rather than Greek, tastes. However, the presence of painted slogans on the vases expressing admiration for young men who were prominent historical figures well known to their Athenian contemporaries (for example, “Leagrus is kalos [beautiful]”), argues against that hypothesis because the inscriptions would be meaningless to an Etruscan consumer (Osborne 1998: 139–41, cf. Robinson and Fluck 1937: 1–14). Perhaps, then, the pottery was resold after use; Webster envisioned Greek aristocrats commissioning sets of drinking equipment for particular occasions, then selling them to traders once they had served their purpose (1972: 42–62, 289–300), like a movie actress bringing her Academy Awards gown to the consignment shop. That may be too ingenious. Another expert concludes: “That there was some sort of second-hand trade is perfectly possible. We have yet, however, to recognize or discover the evidence for how it was operated” (Boardman 1979: 34). In short, the question of how these vases got to their resting places in Italian graves is a challenging one. We must keep their find-spots in mind, for it was this selective appeal to members of another culture that ensured preservation.

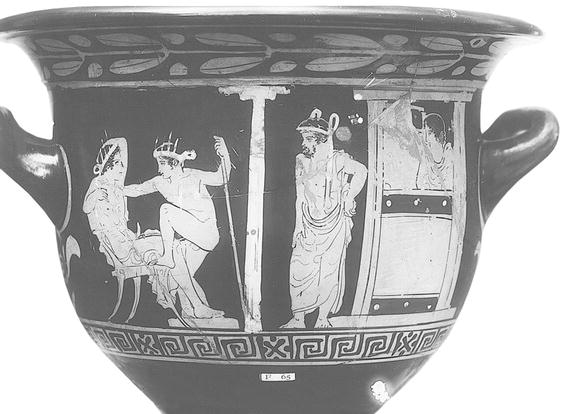

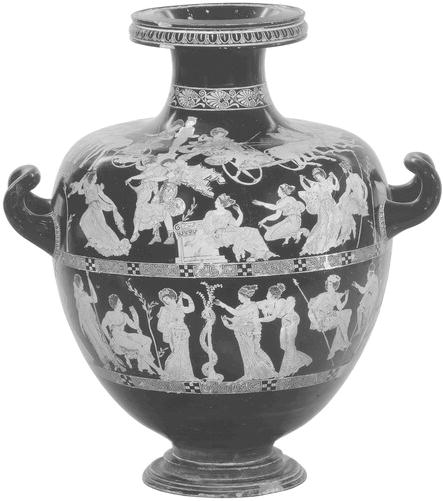

Erotic scenes fall into three general subject categories. First, there are images of pursuit featuring gods, goddesses, or heroes running after youths or women who look back in alarm. Although sex is the pursuer’s implicit goal, representation confines itself to the chase or the moment of capture; with three exceptions, subsequent sexual congress is never shown. 7 Keuls reads these scenes as glorifications of male dominance (1985: 47–55). If so, beholders would be expected to identify vicariously with the pursuing figure, especially in such scenarios as that of Zeus and Ganymede. Abduction, however, can also symbolize a transition to a new mode of existence. When the Athenian hero Theseus, dressed in the costume of an ephêbos or youth undergoing military training, pursues a girl, elements in the picture allude to the marriage ceremony that integrates both “uncivilized” young man and “wild” maiden into the community (Sourvinou-Inwood 1987). Figures of Peleus capturing the sea nymph Thetis, and Boreas, the North Wind, swooping down on the Athenian princess Oreithyia, are found on drinking equipment like the kalyx krater in fig. 3.1 (Boston 1972.850) and may hint at the intoxicating effects of wine. Yet the same mythic scenes are found on vessels used by brides as they prepare for the wedding.

In a funerary context, rape of a mortal is an obvious metaphor for the abruptness of death but may also, through references to the myth of Persephone, hint at salvation and apotheosis. Images of Eos, the dawn goddess, catching up her mortal lovers Tithonus or Cephalos have been read as transgressive fantasies of an adult son’s return to the nurturing mother (Stehle 1990: 101–2). Finally, portrayals of Eros as pursuer that show the god pressing up against or forcibly copulating with a captured youth underscore the uncontrollable force of desire by violating a fundamental artistic taboo (Shapiro 1992: 68–70). Consequently, the theme of “erotic pursuit” must be dealt with in context, for it has so many different implications that treating it simply as an expression of gender ideology is overly reductionist.

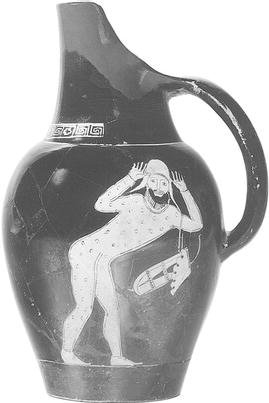

At the other extreme of unreality, vase painters depicted the sexual practices of satyrs. The satyr, a member of Dionysos’ entourage, combines donkeylike features – pointed ears, tail, a gigantic and perpetually erect penis – with the snub-nosed, bearded face and crouching posture of a man. With his insatiable appetite for wine and sex, he embodies the bestial element in humanity. Satyrs freely indulge in acts rarely, if ever, performed by human figures on vases, including masturbation, same-sex oral and anal coitus, and couplings with deer and donkeys. The tenor of these illustrations is usually humorous: on side B of a red-figure cup (Berlin 1964.4, ARV 2 1700; fig. 3.2), one pair of satyrs engages in fellatio, a second in sodomy, while the odd satyr out advances on a sphinx who is actually not part of the scene, but instead a feature of the decorative frame.

In scenes of aggression, satyrs brandish huge members as weapons. Their dealings with maenads, female worshippers of Dionysos, are complex: in the late archaic period satyrs and maenads are shown dancing together or occasionally engaged in sex, but during the early fifth century relations become strained (McNally 1978). Maenads now flee or defend themselves vigorously (Munich 2654, ARV 2 462/47, Keuls 1985: fig. 310). A satyr may sneak up on a sleeping maenad, but it is likely that she will wake and fight him off before he consummates his desire (Boston 01.8072, ARV 2 461/36, sides A and B). Thus the interaction of satyrs and maenads is informed by a dynamic of hostility and, for the former, constant frustration (Lissarrague 1990: 63). All of this is “funny, by Greek standards” (Brendel 1970: 17). Yet the viewer may also have been expected to recognize aspects of himself in the satyrs and ruefully empathize with their plight; comparable self-deprecation is detectable in iambic verse and satyr-dramas (Hedreen 2006).

The satyr’s grossly swollen organ epitomizes his shamelessness. Greek men went around in public decently clothed, but artistic practice allowed males, under certain circumstances, to be portrayed either completely nude or at least with genitals exposed.8 In Greek art the standard of beauty for the male genitals, especially those of attractive youths, was a short, thin, and straight penis with a scrotum of normal size (Dover 1978: 125–35). Gods and heroes conform to the same physical ideal. The aesthetic emphasis given to the penis indicates that its depiction had symbolic ramifications. For a youth, its smaller size relative to that of an adult man suggests modesty and deference, but in its straightness, like that of a sword, it implies suitability to be a warrior. Despicable figures such as slaves and gnarled old men have ugly penises, blunt, clubbed, and twisted. If the satyr’s permanent state of arousal makes him ludicrous, the human males who display erections on vases might also be targets of ridicule, since they too exhibit a brutish susceptibility to desire. Nevertheless, we hear of gangs of well-born young men jokingly calling themselves ithyphalloi (“hard-ons”) and autolêkythoi (meaning uncertain, but doubtless crude)9 as an affront to social norms (Dem. 54.14). Thus, while the satyr served to remind drinkers of the vulgarity of excess, he was also, to use Dover’s expression, a convenient trigger for “penile fantasies” (1978: 131).

The third and largest category of sexual motifs comprises homoerotic and heterosexual encounters between human beings, covering all stages of the relationship from courtship to intercourse, and presented in either idealized or vividly frank terms. Since the treatment of this material displays significant variations over time, we must necessarily proceed chronologically in dealing with it. However, it may be helpful at this point to mention one interpretive theory put forward as a framework for approaching the entire corpus of erotic imagery on Attic vases. Calame (1999 [1992]: 72–88) discovers a homology of purpose between the paintings on the tableware used at the symposium and the poetry recited there. In Chapter 2 we saw that sympotic verse falls into two major types: love poetry employed as a vehicle of seduction, or a means of forging camaraderie through an appeal to shared amatory misfortune, and blame poetry, which defines the hetaireia as unique and privileged by mocking and expelling outsiders. One can draw a similar iconographic distinction between ritualized love in scenes of courtship and unbridled copulation featuring or imitating satyr sexuality. Thus, according to Calame, the image that pays tribute to the beloved by representing him as an attractive youth wooed by an attentive suitor – perhaps with an inscription remarking upon his beauty – reinforces the message of the love poem that attempts to win him over and persuade him to enter upon a friendship with the erastês. Images of drunken excess, on the other hand, were like blame poetry in that they were “designed to pour sexual derision upon symposium drinkers who gradually succumbed to the power of alcohol and would in consequence soon be reduced to the bestial state of satyrs” (1999 [1992]: 87). While this formulation does not cover all instances of erotic imagery – it says nothing of the large role in sympotic scenes played by the courtesan or hetaira – a general correlation between love poetry and romantic dalliance, on the one hand, and blame poetry and priapic lust, on the other, may help us to sort out the wide range of images we must consider.

Lines of Sight

Before we begin to analyze erotic subjects on vases, we should briefly investigate Greek theories of erotic arousal in order to grasp the implied connection between sexually provocative visual materials and their reception by the beholder. Sight is the mechanism by which desire is activated. Whether the eye sends out fiery rays that rebound from the object to generate ocular images, as the Pythagoreans taught, or the object itself gives out emissions from its surface that strike the eye, an explanation favored by the atomist philosophers, the effect of beauty glimpsed is to inflame the beholder. Both forms of the process are mentioned in the archaic lyricists: in Alcman 3 Astymeloisa’s perceived glance melts the onlooker, while in Sappho 31 the speaker is thrown into confusion by her own glance at the beloved. Ibycus, for his part, makes Eros himself cast the fleeting look that provokes desire, a conceit that removes the love object from consideration so as to concentrate exclusively upon the lover’s sensations (PMG 287).

In Plato’s Cratylus Socrates ingeniously derives an etymology of “erôs” from the verb eisrheô “to flow in [through the eye]” (420b). The operations of desire in the Phaedrus extend that physiological principle into the realm of metaphysics. According to Socrates, the madness of Eros inspires the soul to perceive eternal realities beyond the world of material bodies. Even if the soul’s awareness of its prior experience of the Good has been muddled and distracted in the course of its earthly incarnation, the sight of mortal beauty impels it to aspire once more to the realm of absolutes. Longing (himeros) causes the wings by which it had followed in the wake of the gods to sprout again. Despite the resulting pain, “when it looks upon the beauty of the boy, and from thence receives particles [merê] that enter and flow into it [which is why himeros is so called], it is moistened and warmed, and lets go of its pain and rejoices” (251c). Untranslatable into English, Socrates’ pun implies that the stream of material emissions given forth by the boy generates a responsive craving for continued stimulus through its kinetic energy.

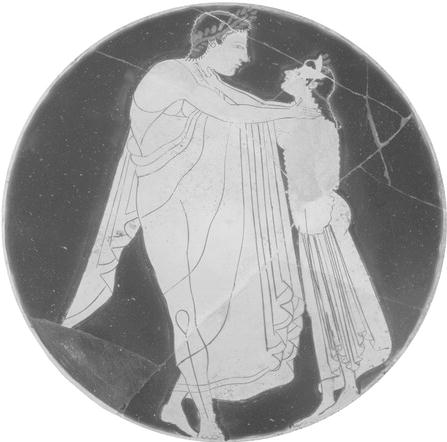

Because the eye is so vulnerable and its effects so potent, the gaze is one of the most charged semantic devices on Attic vases. Eye contact denotes an emotional bond between any two individuals – mother and child, for instance – and is instrumental in depicting the nuances of love relationships. Partners feeling mutual desire look deeply into each other’s eyes (Berlin F 2269, ARV 2 177/1; fig. 3.3). Virtuous boys being courted keep their eyes downcast while their lovers gaze fervently at them. Scenes of pursuit (such as fig. 3.1), represent the victim looking back, possibly to entreat the pursuer, but possibly also hinting at consent.

Direct eye contact can also draw viewers into the action. Some pictures show a single participant looking out full face at the spectator. Breaking artistic illusion with its overt recognition of being observed, frontality can be employed for pathos (as when the companion of an abducted maiden gestures outward helplessly), to heighten erotic tension, or to comment ironically upon the action itself. In one homoerotic courtship scene, the erastês turns away from his beloved to confront us, displaying great strain in his features (London E74, ARV 2 965/1; Frontisi-Ducroux 1995: 128 and fig. 105): we sense a patent bid for sympathy. Women bathing or sitting in the protected ambience of the women’s quarters stare out at the trespasser who breaches their privacy. Satyrs depicted in the frontal position have grotesque erections, a sign of their own exhibitionism but also a sly dig at the prurience of the audience (Lissarrague 1990: 55–6; Frontisi-Ducroux 1995: 108, 111–12). Bystanders in profile whose looks and gestures direct attention to acts of copulation going on around them also drive home the connection between sex and spectacle. Such repeated acknowledgments of the viewer’s presence remove erotic scenes from the category of mere decoration; they become a key part of the dialogue of the symposium.

Birds of a Different Feather

In the ancient Mediterranean world, the phallos or stylized replica of the male sexual organ was a familiar and potent sign. Because Greeks associated it with fertility, the phallos was a major feature of Dionysiac cult, worn by actors in comedies presented at Athenian dramatic festivals and carried in procession at the Rural Dionysia (Ar. Ach. 237–79, Plut. De cupid. divit. 527d). Herms, square pillars bearing the head of Hermes, were equipped with phalloi calling attention to their protective function; the mutilation of these figures in 415 BCE, on the eve of the Athenian expedition against Syracuse, triggered fears of a conspiracy against the state (Thuc. 6.27.3). As might be expected, phalloi appear on painted pottery, perhaps as good luck charms, but more often in contexts that leave no doubt of their primary import. On a circular pyxis lid from Athens a winged phallos is surrounded by three triangular shapes representing the female genitalia, dotted with black lines to suggest razor stubble. Below the phallos is the inscription “Philonides,” a masculine name, while the pudendum to its left is circumscribed by hê aulêtris anemône, “the flute-girl Anemone.” Scholars see in it a parody of the Judgment of Paris (Kilmer 1993: 194; fig. R1189).

Wings added to the phallos, indicating erection, hint that the gravity-defying member has a mind of its own (Arrowsmith 1973: 136). The conceit became goofy when artists by retracting the foreskin and transforming the glans into a staring eye created the phallos-bird. That product of vigorous male imagination is often found in the company of female figures, sometimes ogling them, sometimes being cuddled like a pet (Dover 1978: 133, fig. R414; Kilmer 1993: 193–7; figs. R416, R1192). We occasionally find even more surreal beasts, such as a horse with a phallic head. Surrogates for the onlooker, these beings reaffirm the male privilege of gazing at women sexually (Frontisi-Ducroux 1996: 93–5). Yet it is noteworthy that the women, far from being offended, are shown treating the phallos-bird with affection. Lewis (2002: 127–8) warns us against inappropriately sexualized readings of women with phalloi and phallos-animals, as they may be a reference to the female citizen’s role in fertility cult – though the respectability of figures portrayed in such circumstances may be open to question. Lastly, Vermeule (1979: 173–5) provocatively associates the phallos-bird with other winged creatures, like the Sphinx and Harpies, who bear mortals off to death. If the bird on the vase eyes the viewer, voyeurism, as practiced by this particular surrogate, is uncomfortably self-referential. What at first seems only a joke may have taken on more complicated resonance, then, as the level of wine in the krater sank.

Flirtation at the Gym

Sir John Beazley, professor of classical archaeology and art at Oxford University from 1925 until 1956, is remembered for one massive contribution to classical art history: through minute analysis of stylistic details, he single-handedly catalogued and attributed the products of hundreds of black-figure and red-figure vase painters to whom he assigned proper or descriptive names (for example, the Kiss Painter, so called for a well-known picture of a youth and girl about to kiss; see fig. 3.3). It is less widely known, perhaps, that he also pioneered the study of homoerotic courtship scenes on vases (Beazley 1947).

Surveying over a hundred examples of such scenes, Beazley divided them into three schematic groups according to the stage reached in the courtship. In Type α, the erastês stands on the boy’s left, knees bent, extending his hands in what Beazley termed “the up and down position”: with one hand he caresses the erômenos’s face beseechingly and with the other he attempts to touch his genitals (Jacksonville AP1966.28.1; fig. 3.4). The boy may react by clutching the erastês’s raised wrist, or he may offer no resistance. Other individuals may observe the pair or dance and cavort around them. In Type β the lover bestows presents, usually in the form of animals – fighting cocks, hares, dogs, and so on – upon his beloved (Rhode Island School of Design 13.1479 side A, ABV 314/6; fig. 3.5). Both types of scenes are closely paralleled in images of heterosexual courtship. Sometimes, in fact, contrasting scenes on the same vase feature courtship of boys and of women; we will examine one example, a cup by Peithinos, shortly.

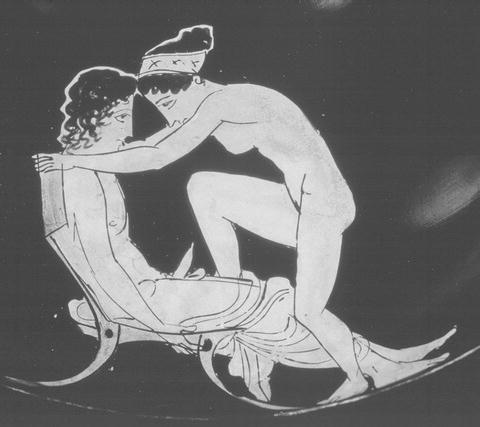

Type γ reveals the man and boy engaged, or on the point of engaging, in copulation. While representations of heterosexual congress may be frank, depicting both oral and anal sex and showing more than one partner involved with the woman at the same time, homoerotic sex is discreet. Lovers may be portrayed facing each other wrapped in one cloak. If intercourse is pictured, the sexual position employed is intercrural – the lover stoops to ejaculate between the boy’s thighs (Mississippi 1977.3.72, side C; fig. 3.6). Pictorial relations are confined to that single method because penetration would dishonor a free youth, and these scenes depict pederastic interaction in an idealized manner (Dover 1978: 100–9). The upright posture of the boy, in contrast to the bent knees and bowed head of the lover, paradoxically suggests that he is the one in control (Golden 1984: 314–15).

Pederastic courting scenes begin to appear on vases during the early black-figure period and reach their height of popularity after 550; they survive the transition to red-figure but show a steep decline in frequency after 500 and virtually disappear by 475 (Stewart 1997: 157). Beazley’s threefold classification holds good for both black-figure and red-figure images, although some thematic differences between products of the two techniques have been noted. It is interesting that the age of the participants grows younger: the mature, bearded erastês of black-figure is replaced at the end of the sixth century by a beardless young man, and his partner, correspondingly, is no longer an older adolescent but sometimes a barely pubescent boy (Shapiro 1981: 135). Since black-figure technique is predisposed to render action, stylized representations of the kômos, the boisterous march through the streets that ended the evening, greatly outnumber symposium scenes of persons drinking while reclining. Though kômos scenes continue to dominate red-figure vases, the number of interior symposium scenes, especially on cups, increases dramatically (Webster 1972: 109–13). Courtship on black-figure vases may occur in a kômos setting, with frenzied symposiasts in attendance; red-figure vases place the action in the palaistra, the gymnastic wrestling-ground (Kilmer 1993: 12, 16–17). Finally, black-figure has been perceived as less restrictive in subject matter than red-figure, providing rare examples of probable heterosexual cunnilingus and physical arousal on the part of the erômenos; in two vases by the Affecter, a sixth-century painter with a highly self-conscious, mannerist approach to his craft, conventions are reversed and the junior partner actively courts the elder (ABV 247.90.691, 715; ABV 243.45; see Kilmer 1993: 2–3, 1997: 42–4; Lear and Cantarella 2008: 68–71). Red-figure, while engaged with a more limited package of themes, provides a much greater range of variations in detail when handling a given motif.

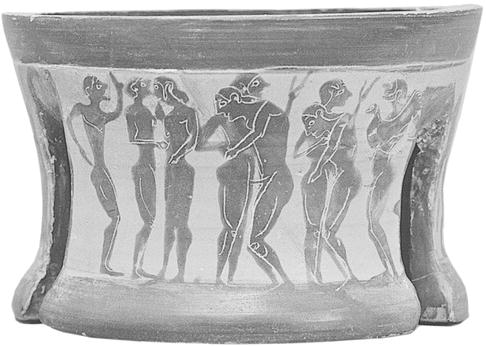

Explicit erotic acts, involving same-sex and opposite-sex pairs, are seen on pottery for the first time on a set of komastic vases labeled “Tyrrhenian amphorae” and dated to the second quarter of the sixth century BCE. There are about 250 of these amphorae, of which only about eleven show such images of group sex, so the percentage of erotica is admittedly a small one. With their exaggerated erections and acrobatic sexual postures, the rows of human figures copulating resemble satyrs. Earlier depictions of padded dancers with artificial phalloi, who may have sung ribald songs at festivals of Dionysos, probably served as the artistic prototype for these designs (Sutton 1992: 9). Thus they appear to be situated firmly within the Greek iconographic tradition. In actuality, however, their indigenous character is contested, with many scholars claiming, again on the basis of find-spots, that they were produced exclusively for the Etruscan market and may therefore be designed to reflect the interests of Etruscan consumers.

Compared with other contemporary Attic vases, Tyrrhenian amphorae are markedly sensationalistic, “specializing in gaudy violence and sexual excess” (Spivey 1991: 142). There are grisly pictures of Trojan War carnage: blood gushes from Polyxena’s throat when she is sacrificed (ABV 97/27) and the body of the Trojan prince Troilus, ambushed and slain by Achilles, lies decapitated on the ground as Achilles and Hector fight over his head (ABV 95/5). Female figures in group copulation scenes participate enthusiastically. One unusual erotic image does not even adhere to the artistic code governing the way sex between two males was normally portrayed at a later date. On the amphora in question (ABV 102/100; Kilmer 1997: 44–5 and pl. 7), a bearded man, bent forward, is being penetrated from behind by a younger, beardless man, while to their right an onlooker fondles his own penis. Since it depicts both age-reversal and anal copulation, the vase has been said to challenge the “orthodoxy” of homoerotic representation in Greek art – although, in so far as it inaugurates a tradition, it might not be expected to conform to standards that were only firmed up later. Alternatively, its subject matter may reflect the mores of a foreign people.

This is a good point at which to bring up the whole issue of “orthodoxy” as it is currently debated by art historians working on Athenian materials with graphic sexual content. The notion that Greek painters never dealt with particular homoerotic motifs – anal copulation, sexual partners of roughly the same age, junior partners taking the initiative in courtship or responding to advances with unmistakable excitement – is wrong, as we have already seen. Dover, who is often credited with formulating that strict orthodoxy, himself calls attention to vases that fall outside the norms he has been discussing: among them, two youths who are clearly coevals, one caressing and entwining himself around the other; a youth gripping the buttocks of another, attempting to pull him down upon his penis; a threesome, all of the same age, in which one inserts his penis between the buttocks of two others crouching back-to-back; a black-figure cup featuring two scenes of boys who respond with enthusiasm to a lover’s caresses (1978: 86–7, 96; figs R200, R223, R243, and B598). DeVries (1997) collected and published scenes intimating that the erômenos, even when not aroused physically, still obtains sensual pleasure from the attentions of his lover and conveys that message through loving gestures; consequently, he should not be considered “frigid.” These anomalous instances, however, do not prove that conventions were not in force: rules may be broken deliberately. While the evidence is slight, it could imply that the existence of the established patterns described by Beazley and Dover occasionally induced painters to deviate from them, possibly for favored customers or as special commissions. A red-figure cup much discussed, for obvious reasons, in recent studies of courtship scenes (Malibu 85.AE.25, fig. 3.7) makes this point nicely: it would not amuse us, as it certainly does, if the junior partner were not expected to be more self-controlled and undemonstrative than his lover.

Allowing for certain differences in setting or treatment, other red-figure scenes of courtship and preparation for copulation between males conform in general to those already seen. The tone of these scenes is often romantic, privileging the bond between the partners and inviting the viewer to empathize with their feelings. There are, however, very few male homoerotic pictures compared to the large numbers of red-figure vases depicting courtship or sex between men and women. Some vases with exceptional features merit detailed comment because of the large amount of scholarly attention they have generated. We can conclude with an in-depth analysis of each.

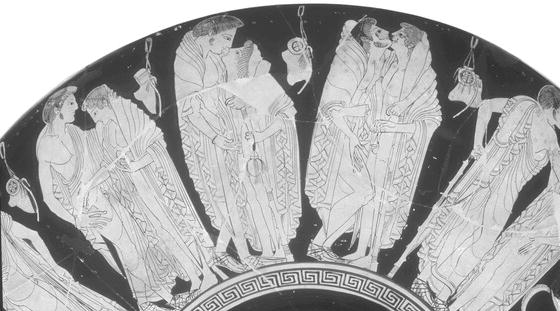

The first vase we have already mentioned in passing. Dating from before 500 BCE, it is a kylix (drinking cup) signed by the painter Peithinos (Berlin 2279, ARV 2 115/1626). On side A (fig. 3.8), four pairs of younger men and older adolescents are engaged in courtship, with a fifth young man at the left standing alone, head bowed. Different phases of seduction are illustrated with great finesse and insight: from left to right, an erômenos accepts apples, a traditional love gift, from an admirer; a couple prepare to kiss and the boy, who holds an aryballos (another type of oil container), guides his lover’s arm and hand toward his genitals; the erastês in the next pair meets with determined resistance as he crouches, attempting to insert his erect penis between the boy’s thighs; the last pair seem at a very preliminary stage, the lover attempting to embrace the boy’s neck while the boy grasps his arm. Strigils, sponges, and aryballoi hung on the walls identify the setting as the palaistra. On side B (fig. 3.9), three heterosexual couples are in conversation: on the far left, a young man with a dog is greeted by a girl; in the center, a girl offers an apple to a youth; at the right, a young man and a girl are speaking to each other, he leaning on his staff, she gesturing with her left hand and picking (nervously?) at her garment with her right. Under the handle beside them, an elaborately carved stool may define this space as a house interior. Dover remarks on the variation in atmosphere, for the youths and girls do not touch each other at all, but seem “immersed in a patient, wary conversation, in which a slight gesture or an inflection of the voice conveys as much as the straining of an arm in the other scene” (1978: 95). Kilmer proposes that the young men involved in adolescent homosexual relationships on the first side have transferred their allegiance to heterosexual partners on the second (1993: 14–15 and n. 6).

The tondo, or circular painting in the bowl of the cup, confirms that this is a coherent program of pictures, for it represents the hero Peleus wrestling with the goddess Thetis (fig. 3.10). According to the myth, Thetis was fated to bear a son who would be greater than his father; Zeus therefore bestowed her upon Peleus instead of sleeping with her himself. Reluctant to marry a mortal, Thetis attempted to escape from Peleus by transforming herself into various wild creatures, but Peleus proved his mettle by holding her firm. On the cup, Peleus grips Thetis tightly around the waist as she changes shape, symbolized by the snakes wrapped around the limbs of the couple and by the small lion emerging from her right hand. The tale is another paradigm for the “taming” of the bride in marriage, and allusion to it surely indicates that the girls being wooed on side B are respectable citizen maidens, probably the betrothed of the young men who now attempt to get to know them better. The Peithinos cup, Kilmer argues, depicts courtship as a learned procedure, whose lessons, discovered through adolescent pederastic relationships, are ultimately put to use in forging “mature heterosexual relationships.”

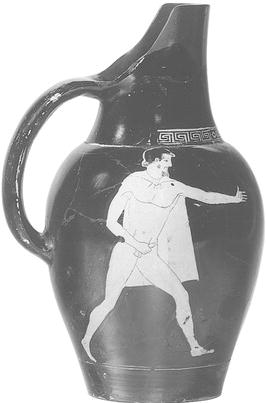

Another controversial ceramic, the so-called “Eurymedon vase” (Hamburg 1981.173) is an oinochoê (wine-pitcher) manufactured in the mid-fifth century. When first published, it was interpreted as a topical memento of Athens’s naval and land victories over the Persians in 467 at the mouth of the Eurymedon River in southern Asia Minor (Schauenburg 1975). On one side, a bearded and cloaked youth is running forward, penis in hand (fig. 3.11). On the other, a man in barbarian garb, quiver hanging from his arm, bends forward while raising his hands beside his head in alarm or surrender (fig. 3.12). An inscription between them represents the running figure as saying, “I am Eurymedôn” and the other, “I stand bent over” (Pinney 1984). The stance adopted by the latter figure is the kubda position facilitating rear-entry, associated with the cheapest form of hasty brothel sex (Davidson 1997: 170). Dover (1978: 105) cites this vase to prove the linkage between anal penetration and dominance in the Greek mind, translating its message as “We’ve buggered the Persians!” Arguments have been brought against this interpretation – the striding person is not a soldier, the barbarian may not be a Persian, the vase may be making only a general reference to Asiatic decadence (Pinney 1984; Davidson 1997: 170–1, 180–2). None of those alternative scenarios, however, accounts in satisfactory fashion for the specificity and the timeliness of the inscription. As a compromise, Smith (1999) suggests that the bearded youth is a personification of the Battle of Eurymedon itself; if that is the correct explanation, the vase establishes unambiguously that anal penetration was an expression of superior power, considered degrading for the passive partner.

One last vase, attributed to the Dinos Painter and produced around 430 BCE, raises an even more complicated set of problems (London F65, ARV 2 1154/35; fig. 3.13). It is a bell-shaped krater and depicts two young men of about the same age about to have sex while a man and woman look on. At the left, a youth wearing a wreath is seated on a chair, grasping its back with his right hand while he crooks his left arm around his head, elbow up. This odd gesture is a popular one in later Roman representations of lovemaking: it signifies the participant’s “openness” to sex (Clarke 1998: 68–70). Another wreathed youth, possibly a little younger, stands before him, steadying himself with a staff as he places his left foot on the chair and prepares to lower himself upon his partner’s erect penis. To their right, next to a column, a bearded man, also wreathed, stares at them, accompanied by a woman, who watches through a half-open door.

The presence of interested non-participants might imply that this is a brothel scene (Keuls 1985: 293). Unusual wreaths worn by the three male figures have been connected to the Anthesteria, a festival associated with youth, wine, and the violation of sexual taboos (von Blanckenhagen 1976: 38–40; Kilmer 1993: 23–4), and that might explain the presence of such unorthodox motifs as male anal penetration and voyeuristic bystanders. Yet the iconography of the sex act on this vase is demonstrably related to that of a slightly earlier work, a vignette of heterosexual intimacy by the Shuválov Painter (Berlin 2414, ARV 2 1208/41; fig. 3.14). There, the intense eye contact between boy and girl indicates that the artist is primarily interested in conveying their mutual affection; the lovers are rendered as wholly sympathetic characters (Kilmer 1993: 154). One wonders, therefore, whether the Dinos Painter intended a spoof of such tender sentimentality. If so, his slyly lascivious rendering of this male couple would burlesque comparable romantic courtship scenes.

Party Girls

In ancient gender studies, it has become something of a truism that Athenians divided adult women into two antithetical categories: citizen wives, guarded by their husbands, and whores, accessible to anyone willing to pay. Keuls popularized this dichotomy by organizing her survey of gender relations around it and emphasizing the “polarization” between wife and whore in the Athenian male’s mind (1985: 204–28). Recently, however, a number of scholars have challenged her formulation, arguing that female social status was not that clear cut and determining it in the case of a given woman not always simple. In fact, the supposed conceptual and social split between “nice” wife and “naughty” whore appears to have been all too easily bridged.

Apollodorus, arguing for the prosecution in the forensic speech Against Neaera – an indictment of an alleged prostitute to which we will return later – classifies women by three separate functions they perform for a man: “We keep companions [hetairai] to give us pleasure, concubines [pallakai] to tend our person on a daily basis, and wives [gynaikai] to produce legitimate children for us and be trustworthy guardians of our possessions” ([Dem.] 59.122). Although this claim is tendentious, since it implies that each function is exclusive of the other two, it indicates that men did form exclusive, lasting unions with women who were not brides conferred by contractual arrangement with their kyrios.10 Because Athenian citizens were legally debarred from marrying foreigners, concubines were, for the most part, resident aliens.11 Like a wife, the concubine lived in the man’s household and the restrictions upon her sexuality were the same as those of a legally married woman: a statute provided that a kyrios who caught a seducer red-handed in his own dwelling could kill the offender with impunity, whether the woman involved was a gynê or a pallakê (Lys. 1.31). For civic purposes, the essential distinction between contractual marriage and concubinage was that children born of the latter arrangement were nothoi, “bastards,” who were non-citizens and unable to share in their father’s estate (Ogden 1996: 34–7, 41–4; Lape 2002–3: 122–6, 130–2). Hence establishing the fact of a mother’s valid marriage – through witnesses, as no nuptial registry was kept – became the central problem in numerous Athenian inheritance suits.

Prostitutes, too, were not all of a kind: the flesh market in Athens was sexually diversified (both boys and women were to be had, though females greatly outnumbered males) and complicated in terms of the social standing of its workers. Women who provided sex for money were designated by one of two nouns: pornai (“whores”) and hetairai (literally “companions”). The clientele of whores was large, anonymous, and generally of the poorer class, while hetairai might enjoy a stable arrangement with one or two men. They operated in distinct environments: the pornê stood in an alley or in a row of girls “posted in battle-line” at the brothel entrance (Eub.[?] ap. Ath. 13.568e–569d), while the hetaira, as her name implies, accompanied a client to a symposium or was hired by the host as an entertainer. Flute-girls, who by law could not receive as a fee more than 2 drachmas (6 obols) a night, were essential to a party, furnishing the music for singing and dancing. Literary and pictorial evidence indicates that some offered sexual services too, but others seem to have been respected professional artists (Lewis 2002: 95–7).12 In short, then, a whore was paid by the deed, an hetaira for an entire evening that might not necessarily include sex, and the status of the latter was therefore considerably higher (Davidson 1997: 94–5). Within this twofold framework there must have been further gradations: for example, free resident aliens working in private establishments would have ranked above slaves kept in state-run brothels, and companions were valued more or less highly based on factors such as age, appearance, talent and education, sexual skills, and personal charisma (Kilmer 1993: 167).

Sites of commercial sexual activity have various names. They may be expressly designated as porneia, “brothels,” but also, more euphemistically, as oikiai or oikêmata, “houses” or “rooms,” or even as ergastêria, simply “workplaces.” The last term indicates that what Athenians found contemptible about providing such services was not the nature of the activity – prostitution was both legal and patronized by Aphrodite – but the fact that it was performed under supervision (Cohen 2006). Citizens did not undertake labor, compensated or not, at the behest of another: managed employment was fit only for slaves (Isae. 5.39; Isoc. 14.48). Hence brothel work was synonymous with slavery. Some female staff, then, might have more than one assigned job; when not occupied with customers, they would be set to another kind of productive task, cloth-making. Several Athenian red-figure vases show clients approaching women who either hold wool-working tools or are accompanied by other women carrying such implements (e.g., Chicago 1911.456, ARV2 572.88; Keuls 1985: 191 and figs. 175, 176). This inference from vase paintings is confirmed by archaeological evidence.

According to Xenophon (Mem. 2.2.4), prostitutes were available throughout the city and not confined to one red-light district. During a noteworthy trial, to which we will return in the next chapter, the prosecutor Aeschines exhorts the jurors: “Look at these fellows there sitting in their cubicles (oikêmata), those who openly practice their trade” (1.74). Apparently a house of male prostitution was visible from the law-court located in the agora. In the same speech we are told that workshops were defined by the business conducted there, so that a space facing the street could be successively a surgery, a smithy, a laundry, a carpenter’s shop, or a porneion (1.124). Yet there may also have been purpose-built brothels, if we have interpreted the material remains correctly. Building Z in the Kerameikos, close to the city wall, was quite likely a brothel during some phases of its existence. It was a commodious structure, having two entrances and two courtyards, banquet rooms, a well, and drains indicating copious water use. In the third building stage, a large number of tiny rooms were constructed along its southern side with an entrance giving direct access from the street; these rooms could be locked. Finds from this area of the building, though few, include dining and drinking ware. However, loom weights and underground cisterns that could be employed for washing cloth suggest that it was also a site of textile manufacture (Glazebrook 2011: 39–41, 46). Adjacent to it is another structure, Building Y, whose ground plan, including elaborately decorated dining rooms, may hint at a similar function.

While the standing of the man or woman working on the streets or in a whorehouse is self-evident, a “companion” of either sex occupies a more slippery position. Aeschines can indict his enemy, the influential politician Timarchus, for prostituting himself as a youth because proof of hetairêsis (living off lovers) is wholly circumstantial. In terms of gender, the male companion assimilates himself to a female (Aeschin. 1.110–11), while the female herself is even more ambiguous: her position oscillates between femininity and masculinity (Calame 1999 [1992]: 115). If freeborn or freed, she is not under a kyrios’s protection; rather, she is autê hautês kyria, “her own mistress” ([Dem.] 59.46). Like a man, she can own and manage property and she has a public presence, for her name is heard in gatherings of men (McClure 2003: 68). In documents and speeches, a living woman is not referred to by name if she is respectable; instead, she is designated as “the daughter, wife, or mother of X” (her closest male relative). This is a rule of etiquette, since men addressing men must avoid implying that they are unduly familiar with someone else’s female kin (Schaps 1977). The hetaira, on the other hand, makes her profits from being notorious, and Apollodorus’ offhand references to “Neaera” and her supposed daughter “Phano” are intended to leave no doubt of their profession. In the first attested use of the expression hetaira, Herodotus, the fifth-century historian, employs it when gossiping about the fabled Egyptian whore Rhodopis – who, contrary to legend, did not, he assures us, erect a pyramid as her monument but did dedicate a tenth of her earnings to Apollo at Delphi, offering a set of iron spits still on view there (2.134–35). By setting up that memorial, Rhodopis was boasting of the distinction she had achieved; in her eyes, fame equaled success. Hence the names of celebrated hetairai turn up, along with those of admired youths, in vase inscriptions. On a wine-cooler signed by the painter Euphronius, four naked women, each identified, are drinking together and one, Smikra (“Tiny”), salutes the beautiful boy Leagrus (St. Petersburg 644, ARV2 16/15; fig. 3.15). Since a reclining woman on another vessel, a cup produced about the same time, is similarly designated, the name is probably that of a real person (Peschel 1987: 77).

We should not think of the image as a group portrait, though, for such scenes are “generic sympotic tableaux given particularity through realistic names” (McClure 2003: 70). Furthermore, representations of an all-hetaira symposium are also “contrary-to-fact” situations, analogous to Aristophanes’ Lysistrata and other gender-inversion comedies in which women assume men’s roles (Ferrari 2002: 19–20). Euphronios shows his subjects reclining in masculine poses and otherwise behaving in male fashion; when Smikra toasts Leagrus, she acts the part of an erastês. Palaesto, another figure in that same scene, gazes directly out at the beholder from over her wine cup; making eye contact, she invites him to identify with her (Kurke 1999: 207–8). Male drinkers can associate themselves with these constructs psychologically because, in throwing their own exclusive party, the women have lost their identity as female “companions” and become figures of indefinite gender. Thus they are vehicles of fantasy capable of mediating the young man’s transition from the homosocial sphere of adolescent pederasty to marital heterosexuality. At the same time, their portrayal as humorously immoderate outsiders facilitates bonding among male spectators (Glazebrook 2012).

Hetairai at the very top of the economic pyramid maintained independent establishments, took prominent men as lovers, and were celebrities in their own right: Davidson, employing a term used by Greeks themselves, calls them the megalomisthoi, “‘big-fee’ hetaeras” (1997: 104–7), but we more commonly refer to them as “courtesans.” Comic plays were written about them, artists painted and sculpted them, anecdotes about their lives and collections of their witty sayings were compiled, and they even became the subject of scholarly treatises. The great era of courtesan idolatry at Athens came later, between 350 and 250 BCE, so we will revisit these women when we move into the Hellenistic period. But it seems appropriate at this point to talk about the meaning of the hetaira as cultural icon, for in that capacity she continues to exercise a spell over modern historians. Earlier in the twentieth century, she was envisioned as an educated and sophisticated “bachelor girl” who conversed with the leading men of Athens, while her sexual life was discreetly played down. Lately she has been applauded for her liberated lifestyle: Garrison portrays her as the incarnation of Athenian “high sexual culture” and surmises that respectable wives adopted her techniques of grooming and lovemaking in order to compete for the attention of their husbands (2000: 121–4, 143–9). How much of this scenario is fact?

Peschel contends that the hetaira is a product of the historical circumstances of the late archaic age, a construct invented just when the public visibility of the citizen wife and mother was being curbed (1987: 362–3). For Kurke, her function is that of an ideological stereotype (1996, 1999: ch. 5). As the counterpart of her aristocratic lover, she is dainty, witty, and beautiful; unlike a squalid pornê, she is at home in the sympotic gatherings of the hetaireia. Her characteristic refinement exemplifies the value attached by the elite classes to a sophisticated hedonism (habrosynê). Because she is the ostensible friend and equal of her admirer, she grants sex as a favor in return for gifts, rather than being paid in cash for her services. Representing the economic relations of client and hetaira as a form of gift exchange removes them from the commercial realm and sets them at the opposite pole from monetary transactions with whores, emblems of the marketplace frequented by the rising middle class. Though Kurke does not deny that the hetaira played a part in Greek entertainments, she believes that the many representations of her in art and literature are not a sign of her actual social importance but instead mark her usefulness as a counter in oligarchic political discourse.

James Davidson’s analysis of the grand hetaira’s role as fantasy object starts from this same opposition of gift and commodity exchange but approaches it as a marketing strategy. He draws his illustrations from a chapter in Xenophon’s Recollections of Socrates (3.11). Socrates visits the house of the courtesan Theodote to behold her fabulous beauty himself. Noting the luxury in which she and her mother live, he asks the source of her income. “If someone who has become my friend [philos] wishes to do me a kindness, that is my living.” Much better than farming, Socrates observes dryly, and proceeds to quiz her about a device (mêchanê) for attracting such friends. Appropriating Theodote’s own semantic field of “gifts” and “friendship” and conspicuously shying away from vulgar allusion to money or sex, he cynically unpacks her term philos and exploits the contradictions inherent in using it as she does. For Davidson, what is revealed by the episode is the subterfuge that underpins the allure of the hetaira. Her very language is a tissue of double-meanings in which no firm truth can be pinned down. By pretending to return favor for favor instead of marketing a service, she avoids the laws and taxes that govern commercial prostitution, and by making herself physically inaccessible, even to the point of withdrawing from the public gaze except on rare occasions, she becomes more and more an object of fascination. The courtesan’s deliberate seclusion assimilates her to the forbidden wife. It is precisely for those reasons that the male artistic imagination fixates upon her, attempting to capture her elusiveness in paint or writing (Davidson 1997: 120–36).

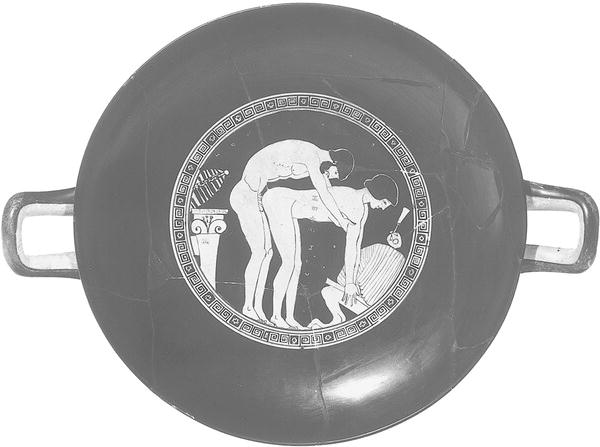

On vases, pictures of symposiasts courting and making love with hetairai – securely identified as such because respectable women by definition did not attend symposia – peaked in popularity around 470 BCE, approximately thirty years after the vogue for pederastic courtship scenes began to decline. Indeed, as the Peithinos cup indicates, images of heterosexual courtship adopted the stances and conventions of earlier scenes in which men had courted boys (Stewart 1997: 156–7). In vase paintings, however, the hetaira is a more paradoxical figure than the boy, sometimes glamorized, sometimes brutalized, even on the same vase. For all her typological similarity to the male symposiast, she is an alien presence in the hetaireia. Lovemaking scenes underscore her inferiority to her sexual partner in significant ways. Although several vases depict face-to-face copulation, with looks exchanged between the partners and the woman taking an active part in the sex act, by far the most common position shown for heterosexual congress is rear-entry – whether vaginal or anal is usually not made clear. While it is true that the position illustrated need not signify a lack of respect for the woman, as prostitutes themselves may have requested anal copulation in order to prevent pregnancy (Kilmer 1993: 33–4), the rear-entry stance requires passivity on her part and implies an emotional distance between her and the man (Sutton 1992: 11). One cup by Douris employing this configuration (Boston 1970.223, ARV2 444; fig. 3.16) indicates through an inscription that the male is fully in control: as he penetrates a woman from the rear, he orders her to “hold still!” (heche hêsychos).13

Two notorious vases show forced copulation in the surroundings of an orgy. On a cup by the Brygos Painter (Florence 3921, ARV 2 372/31; Keuls 1985: figs. 167–70; Kilmer 1993: R518), a man penetrates a woman from the rear while apparently shoving her head down toward the penis of another man facing her, and next to them a third man threatens a squatting woman with a stick. The cropped hair of both women suggests that they are slaves. On the more fragmentary reverse, a man beats a crouching woman with a sandal. Side A of the Pedieus Painter’s cup (Louvre G13, ARV 2 86; fig. 3.17) pictures two sexual triads, the woman in each case compelled to perform fellatio on one youth while another enters her from behind. Side B is dominated by a fellation scene in which the youth being serviced seems almost more intent on keeping his drinking horn from spilling. Unlike the slim youthful hetairai in other paintings, the women involved are middle-aged and fat, and the wrinkles around their mouths graphically indicate the difficulty they have in accommodating the men’s oversized penises (Peschel 1987: 62). Sutton observes that the hierarchy of male over female here is reinforced by control of young over old, free over slave, and employer over employee; it is no wonder that these social inferiors submit without protest (1992: 12).

Several other vases repeat the motif of a threatened or actual beating with a sandal. As enumerated and discussed by Kilmer (1993), these include two, possibly three, male homoerotic scenes (104–7); at least three scenes in which a man wielding a sandal accosts a woman who resists him (108–10); three other scenes of heterosexual foreplay, each with a woman and two men, one of whom brandishes a sandal (110–13); and one instance where a woman uses a sandal on a man with a partial erection (121–4). Except for the scenes in which the male detains a reluctant partner, these images leave it unclear whether the sandal is being employed as a weapon or a mild sexual stimulant, although the one in which the girl swats the man (Kilmer 1993: R192) must involve an attempt at arousal. A last picture, which Kilmer deems “far and away the most violent of the scenes of foreplay” (1993: 113) shows a naked youth yanking a woman’s hair with one hand while gripping a sandal with the other (Milan A8037; Kilmer 1993: R530; Lewis 2002: fig. 3.26). The grimace on the woman’s face and her pleading gestures indicate that she feels pain and fear; the youth is hauling her forward, probably with the idea of making her fellate him. Like the portrayals of rape on the two “orgy cups” discussed here, this painting leaves no doubt that sadistic force is being exercised against an unwilling victim.

How was the viewer expected to react to these scenes? According to Keuls, they are descriptive, recording what might well have occurred frequently at banquets. She cites an incident reported in Against Neaera to demonstrate that “sexual violence was an integral part of the symposium and Athenian society had a high degree of tolerance for it” (1985: 182). There Apollodorus claims that Neaera and her then protector Phrynion once attended a party at which “many had intercourse with her while she was drunk and Phrynion was asleep,” including even the servants who waited on tables ([Dem.] 59.33). If vase paintings do reflect conventional reality, an observer would probably associate himself with the dominant male figures rather than their victims. However, the penises of the youths involved in acts of fellatio on the Pedieus Painter’s and the Brygos Painter’s “orgy cups” are comically exaggerated and resemble those of satyrs, barbarians, and slaves. Caricature puts them into the category of the unsightly and disgusting and may indicate that their conduct is to be regarded with disapproval (Brendel 1970: 27; Kilmer 1993: 156–7).

Because of the great symbolic power attached to the figure of the hetaira, scenes in which she appears can also be read as ideological pronouncements. Stewart sees images of sexual violence as visual demonstrations of gender and class supremacy that promote male bonding through fantasy (1997: 165). Kurke (1999: 208–13) agrees that objectification of women is a tactic for fusing the male sympotic group, but points out that the Pedieus Painter’s cup showing women abused on its exterior surface contains in its tondo a delightful picture of a young man and a female lyre player strolling along in perfect harmony (see frontispiece). What are we to make of a cup with such an idyllic tondo scene and such external representations of drunken brutality? Some sort of contrast was unquestionably intended: we might bear in mind that the exterior was visible to all, while the interior image would reveal itself only to the drinker, emerging as he drained his wine. Iconography, Ferrari argues, can be as metaphoric as language (2002: 61–86). Perhaps neither the charming interior nor the violence on the exterior was meant to be understood literally. In any case, vase paintings do not chronicle the vicissitudes of the hetaira’s life but instead use her as a tool for reaffirming sympotic values and aspirations during an era of intense class conflict. Her treatment in art mirrors the contradictions within that value system.

In the Boudoir

When we move outside the symposium to consider pictures of women in other settings, alone or in company, problems of interpretation are compounded. Even in a non-sympotic situation, one might think, it should at least be easy to tell wives from hetairai, but it is not. Indeed, the barrier between the two was apparently permeable in life. Free hetairai could enter into long-lasting concubinage relationships and became virtual common-law wives, legally off-limits to other men. Neaera, if we can believe Apollodorus, was once a slave prostitute in Corinth. Her prosecution for attempting to pass herself off as the lawful wife of an Athenian citizen indicates that below a certain social level the boundary separating citizen women from foreigners and respectable from non-respectable women was blurred; this explains why Apollodorus is so anxious to stick females into neat pigeonholes. Naturally, hostile speakers do not bother to draw fine lines but use the pejorative term pornê for any woman on whom they wish to cast aspersions. The biographical tradition surrounding Aspasia of Miletus, partner of the influential Athenian politician Pericles, reveals that ambiguity could operate even at the highest levels. Henry (1995: 9–17) constructs an extremely plausible case for her being a resident alien of distinguished background living in a concubinage union with Pericles, yet jokes about her as prostitute and madam were current during her lifetime (Ar. Ach. 526–7).

Unless their respectability is unmistakably indicated, one theory holds, all women on red-figure vases, at least until the middle of the fifth century, are supposed to be hetairai. Like prostitutes, many vase painters were themselves slaves or foreigners; the Kerameikos, home of the industry, was also a district with numerous brothels; and the aristocrats who bought ceramics purchased equipment for symposia, not gifts for wives. Thus the painters’ own social standing, the neighborhood in which they worked, and the market they served created a natural bias toward representing hetairai as a class (Williams 1983: 97). Sinister explanations can then be found for the activities in which women are engaged. Obviously female bathers are not respectable because citizen wives would never be shown in the nude. Men approaching a woman purse in hand are about to buy sex; and women spinning in a domestic interior are not hard-working wives but whores in a brothel waiting for customers (Keuls 1985: 258–64).

This sweeping presumption has been challenged. For one thing, the purpose to which an iconographic motif is put may change. Scenes of single naked bathers decorate the interior of wine cups manufactured in the late sixth and early fifth centuries, and accompanying images of dildoes (or, in one instance, a set of disembodied male genitals in the background) leave no doubt that such representations are a kind of “soft porn.” Later, however, the same motif of women bathing becomes domesticated. Several women now wash together at a large basin, and the vessel on which the scene appears is a hydria or other piece of toilet equipment. These vases were consequently designed for use within the oikos by women (Sutton 1992: 22–4). Portrayal of respectable women as desirable reflects a growing tendency to celebrate the presence of erôs in married life (Lewis 2002: 149), and putting these sensuous images on household vases serves the interests of the polis by presenting female viewers with “appropriate” constructions of their sexuality (Petersen 1997: 44). In both literature and ritual, bathing followed by adornment had long been symbolically associated with the nubility of goddesses (Ferrari 2002: 47–52). By the late fifth century, then, a maiden preparing for her wedding by taking the nuptial bath can be shown naked. The girl’s exposure to the viewer’s eye is a reminder of her vulnerability during this crucial transition, for in Greek myth and ritual the association between marriage and death, especially for maidens, was a deeply rooted one. Stewart may therefore be right to define the nude female in Greek art as the “liminal female, lacking in or deprived of acculturation” (1997: 41), provided we add that perceptions of what is liminal – prostitutes, brides – can vary over time.

The purse (which Keuls terms an “economic phallus”) is an equally ambiguous indicator. Lewis points out (2002: 91–8) that females appear in scenes of commercial life; for example, selling oil (Berne 12227, ARV2 596/1; Lewis 2002: fig. 3.1). If a man is talking to a woman with purse in hand, then, she may be a vendor and he a customer, with the purse pointing to an ordinary business transaction. When the woman being approached is represented with veil, distaff, and wool basket, the accoutrements of the virtuous housewife, this iconographic puzzle becomes even more complicated. Since some brothel employees were also wool workers, there was probably a conceptual link between those two activities in the popular imagination (Davidson 1977: 86–90), hence the far-fetched theory that nonrespectable women – so-called “spinning hetairai” – posed as matrons equipped with the implements of domesticity in order to arouse customers (Keuls 1985: 258–9). It is much more likely, though, that the purse – if indeed it is a purse – is an abstract symbol of wealth, and as such, appears in different types of domestic scenes, including those where a man of property courts a prospective bride and those in which he is represented as head of a household and is joined by his wife as mistress of the oikos (Lewis 2002: 194–9). Alternatively, this pouch could be thought to contain knucklebones, the ancient equivalent of metal or plastic jacks. Playing with them was a child’s pastime, but because the activity was associated with youth and charm, knucklebones might be a courting gift. If that is the case, the females in these idealized scenes are marriageable girls, whose wool working testifies to their industriousness, a trait as necessary to the desirable young woman as beauty and modesty (Ferrari 2002: 12–60).

While some pictographic markers are plain and unequivocal – in tableaux of wedding preparation, the bride, with her crown and special sandals, is easy to recognize (Oakley and Sinos 1993: 18) – others give mixed messages. Status, in particular, is hard to determine. Short hair is an indication of slavery, but the hairstyles and headdresses worn by hetairai in sympotic scenes vary widely at different periods, with hair sometimes short, sometimes long, perhaps following current fashion (Peschel 1987: 358–9). Literary sources state that the mistress of the household supervises her female slaves, who perform the manual labor. Yet images of domestic work show pairs of women similarly dressed toiling together, with no sign that one is a slave. In late fifth-century pictures of wealthy women at their toilette, the matron is distinguished only by the fact that she is seated, while her attendants are garbed as elegantly as she is (Lewis 2002: 79–81, 138–41).

All-women scenes that appear to have homoerotic implications can be construed differently depending upon the audience projected. Kilmer (1993: 26–30) describes two cups portraying women dressing or perfuming each other; in each picture he finds subtle signs that the women are sexually aroused. Another is more explicit: on one side women are bathing, on the other they play with a phallos-bird beneath dildoes hanging on the wall. These images, he emphasizes, are products of male fantasy produced for men that offer no evidence for real women’s homoerotic activities. Yet a hypothetical female viewer might have been gratified by such representations of intimate contact (Petersen 1997: 69). Scenes on vases intended for women’s use show female companions expressing fondness by touch. In the picture of women conversing on the late archaic Polyxena sarcophagus (fig. 2.2), the figure on the far left gently places her hand upon the adjoining woman’s back; such stroking occurs frequently in scenes set in the women’s quarters. Rabinowitz identifies two main contexts: the adorning of the bride, an occasion suffused with romantic intensity, and a musical concert, where one listener expresses the mellow feelings evoked through song by embracing a friend (2002: 117–26). On these vases, she notes, there are no explicit pictures of genital activity, nor should we expect them. Yet vase painters constantly impart shared fondness to women’s homosocial environment – evidence, perhaps, that love between women, possibly though not inevitably sexual, was taken for granted by men (2002: 148–9). Though it comes from a much later period, one brief observation about art confirms that men read images of women’s physical contact with other women in just that way. In his account of the early fifth-century murals by Polygnotos in the Lesche at Delphi, the second-century CE travel writer Pausanias describes two mythic heroines envisioned in the Underworld: “Below [the image of] Phaedra is Chloris reclining in the lap of Thyia. Whoever says the women when they were alive felt affection [philia] toward each other will not be mistaken” (10.29.5).

Bride of Quietness

After 450 BCE, the themes of red-figure scenes involving women change dramatically, perhaps driven by a shift in clientele. Although images of sympotic sexual activity continue to be produced, there are statistically far more scenes of women in domestic surroundings. The usual explanation (though it has been disputed) is that the foreign market, especially in Etruria, had collapsed, and vase painters were now manufacturing more wares for local household use and catering chiefly to feminine tastes (Boardman 1979: 37; Sutton 1992: 24–32). Vases characterized as “women’s pots” – vessels specifically used in the wedding ritual as well as perfume containers and cosmetic boxes – are primarily found not overseas but in Attica, where they were preserved as religious or funerary dedications or excavated as fragments from housing sites.

Wedding imagery appears on vases as early as 580–570 BCE and, unsurprisingly, retains its popularity throughout the entire epoch of Attic vase production. During the black-figure period, the marriage procession with the couple in a chariot, escorted by relatives and guests, was the dominant theme: it encapsulated the public side of the occasion, the transfer of the bride from one oikos to the other. Closely linked as it was to religious ceremony, such iconography was extremely conservative: for half a century after the introduction of red-figure technique, Oakley and Sinos point out, artists persist in using black-figure for nuptial scenes (1993: 44). Early red-figure vases, while continuing to show the procession, also introduce other themes, such as the ceremonial bath and dressing of the bride. More important, they begin to focus upon the couple’s regard for each other as manifested through an exchange of glances. Thus a preoccupation with subjectivity emerges.

While legitimate children had to be born of a contractual marriage, nothing prevented members of the aristocracy from continuing to form valid marriage alliances with leading families of other city-states. Pericles’ citizenship law of 451/50 BCE decreed, however, that children with full citizen rights could only issue from the marriage of two Athenian citizens.14 Technically, those born of a union with a non-Athenian woman, no matter how high her rank, were henceforth children of a pallakê. Increased consciousness of the importance of marriage to the state as well as the individual household was subsequently reflected in nuptial imagery. In the new wedding scenes from the second half of the fifth century, “sexuality is shown in a polite but unmistakable manner as the bond that ties together the basic unit of the polis” (Sutton 1992: 24). Erôs was thought to play a leading part in female acculturation: out of desire for her husband, the bride surrenders and agrees to receive the “yoke.” The Washing Painter, who specialized in marriage vases, pictures the god Eros as the bride’s companion. Sometimes he assists her as she readies herself for the ceremony (Athens 14790; Oakley and Sinos 1993: fig. 23); his attentions guarantee her loveliness. On vases by other painters, such as the loutrophoros intended to hold the water for the nuptial bath shown in fig. 3.18 (Boston 03.802), Eros accompanies bride and groom as they make their way to their new home, an obvious symbol of the mutual physical attraction springing up between the couple. Wedding iconography also features Peitho, “Persuasion,” as an attendant of Aphrodite and Eros. What insures the fecundity of the oikos and the strength of the polis is sexual energy channeled into social uses (Thornton 1997: 153; Calame 1999 [1992]: 125–9), as figured by the activities of personified Desire and Persuasion.

Increasingly, however, Eros also becomes a participant in stylized scenes of domestic life, an inconsequential emblem of feminine grace. Although the context may be mundane, Lewis notes, female figures are often given the names of heroines or divine personifications; thus it becomes harder to differentiate real women from mythic personalities (2002: 130). In these scenes, too, “settings are abstract and indistinct, all women look very much the same, and the imagery is dominated by a single ideology of wealth and leisure” (2002: 134). On another set of vases, Aphrodite and her whole retinue become avatars of romance. The Meidias Painter, whose ornate style was much in fashion during the last quarter of the fifth century, places the goddess in an outdoor landscape with her lover Adonis, or presiding over the rape of the daughters of Leucippus by the Dioscouri (London E 224, ARV 2, 1313.5; fig. 3.19). There the abducted girls “put up a token of resistance but not enough to dishevel their delicate transparent gowns and neat coiffures” (Pollitt 1972: 123). As an allegory of marriage, the vase turns the ordeal of the bride’s transition from maiden to wife into a palatable fantasy. While tragic poets composing at this time portray Aphrodite as a terrible and irresistible power threatening the community, her role in pictorial art, like that of Eros, has been modified to suit sentimental needs.

Conclusion

To explain revolutionary changes in erotic iconography during the two centuries we have surveyed, art historians have turned to the civic realm. Intercourse scenes first appear about 570 BCE on vases destined for export to Etruria and are then transferred to other kinds of sympotic equipment. Between 560 and 550 the encounter of erastês and erômenos materializes as a leading theme. Shapiro (1981: 135–6) observes that this time span coincides with the early rise to power of the tyrant Pisistratus, who showed special favor to the prosperous nobility. The frequency of pederastic imagery thus mirrors the economic and social power of the elite under the reign of the despot and his sons. In the late sixth century, scenes of heterosexual congress also increase in popularity, but their implications differ greatly. Through the type of the hetaira as “outsider,” group orgies celebrate male homosocial bonding (Stewart 1997: 163), while abuse of prostitutes affirms hegemony over inferiors, an indication that class relations were already troubled (Shapiro 1992: 57). It is also noteworthy, however, that some images depict youthful heterosexual pairs with great tenderness, in a manner just as romantic as scenes of homoerotic courtship.

Chapter 4 will show that aristocratic sympotic culture was already losing ground at Athens, as evidenced by the decline in demand for pederastic vases. By the time of the Persian Wars, public opinion had turned against a lifestyle of ostentatious self-indulgence. With the full emergence of the Athenian democracy, a new personal ethic began to take shape: the notion that a head of household must display self-control through rational regulation of pleasures was gradually adopted as a central tenet of democratic egalitarianism. For Stewart (1997: 171), it is the triumph of this mentality that explains the disappearance of erotic vases, except as isolated examples. Other factors may have given rise to the appearance of new motifs. Under the radical democracy, idealization of domestic life as a focus of social stability produced a positive emphasis on female sexuality within marriage (Sutton 1992: 33). Lewis (2002: 133) proposes that the decline in elaborate exported pots allowed ceramics intended for internal household use, which were limited in respect to thematic material, to become more conspicuous. Finally, Pollitt (1972: 125) believes that the extravagances of the Meidias Painter were a response to the difficult moral and political issues posed by the Peloponnesian War, and Burn (1987: 94–6) sees in them a symptom of a deeper existential malaise springing from urbanization. Whatever the plausibility of such conjectures, it seems reasonable to believe that vase paintings do offer glimpses, although fleeting and debatable ones, into the erotic fantasy life of some Athenian consumers, male and, more speculatively, female.

Discussion Prompts

1. Iconography on Athenian vase paintings makes use of individual elements in a scene to convey additional information to the spectator metaphorically. In the illustrations to this chapter, identify specific items that serve that function.

2. The folk art of indigenous peoples is highly valued by North American and European collectors precisely because it reflects the aesthetics and belief-systems of cultures unlike our own. Judging by descriptions of Etruscan culture in the present book, what differences might have led Etruscans to regard Attic pottery as decidedly collectible, so much so that it was used as grave goods?

3. By far the majority of pederastic scenes on Attic symposium ware involve courtship at various stages rather than consummation. Does this fact indicate that consumers were more intrigued by romantic pursuit as opposed to outcome? Or are there other factors that might help to account for the relatively low quantity of explicitly sexual vignettes?

4. “Escapism” is a frequently invoked explanation for the growth in popularity after 450 BCE of interior scenes showing women occupied in domestic pursuits. In this chapter, though, scholars have suggested other possible reasons, economic and political, for this shift in preference. Discuss how they may have worked together to bring about change.

Notes