North Norway

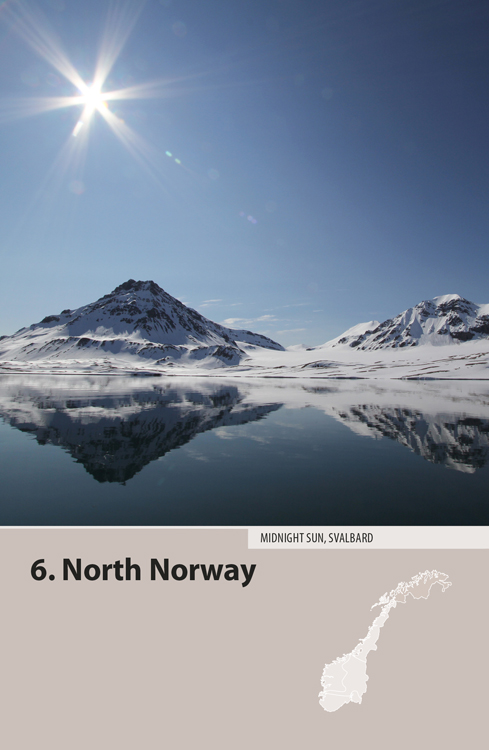

Karl Baedeker, writing a hundred years ago about Norway’s remote northern provinces of Troms and Finnmark, observed that they “possess attractions for the scientific traveller and the sportsman, but can hardly be recommended for the ordinary tourist” – a comment that isn’t too wide off the mark even today. These are enticing lands, no question: the natural environment they offer is stunning in its extremes, with the midnight sun and polar night further defamiliarizing the often lunar-like terrain. But the travelling can be hard going, the individual sights geographically disparate and, once you do reach them, rather subdued in their appeal.

The intricate, fretted coastline of Troms has shaped its history since the days when powerful Viking lords operated a trading empire from the region’s islands. And while half the population still lives offshore in dozens of tiny fishing villages, the place to aim for first is Tromsø, the so-called “Capital of the North” and a lively university town where King Håkon and his government proclaimed a “Free Norway” in 1940, before fleeing into exile. Beyond Tromsø, the long trek north and east begins in earnest as you enter Finnmark, a vast wilderness covering 48,000 square kilometres, but home to just two percent of the Norwegian population. Much of this land was laid to waste during World War II, the combined effect of the Russian advance and the retreating German army’s scorched-earth policy, and it’s now possible to drive for hours without coming across a building much more than sixty years old.

The first obvious target in Finnmark is Alta, a sprawling settlement – relatively speaking, of course – and an important crossroads famous for its prehistoric rock carvings. From here, most visitors make straight for the steely cliffs of Nordkapp (the North Cape), ostensibly but not actually Europe’s northernmost point, with or without a detour to the likeable port of Hammerfest, and leave it at that; but some doggedly press on to Kirkenes, the last town before the Russian border, where you feel as if you’re about to drop off the end of the world.

The main alternative from Alta is to travel inland across the eerily endless scrubland of the Finnmarksvidda, where winter temperatures can plummet to -35°C. This high plateau is the last stronghold of the Sámi, northern Norway’s indigenous people, some of whom still live a semi-nomadic life tied to the movement of their reindeer herds. You’ll spot Sámi in their brightly coloured traditional gear all across the region, but most notably in the remote towns of Kautokeino and Karasjok, strange, disconsolate places in the middle of the plain.

Finally, and even more adventurously, there is the Svalbard archipelago, whose icy mountains rise out of the Arctic Ocean over 800km north of mainland Norway. Once the exclusive haunt of trappers, fishermen and coal miners, Svalbard now makes a tidy income from adventure tourism, offering everything from guided glacier walks to hard-core snowmobile excursions and husky riding: journeys that will take you out to places as remote and wild a spot as you’re ever likely to get in your life. You can fly there independently from Tromsø and Oslo at surprisingly bearable prices, though most people opt for a package tour.

As for accommodation, all the major settlements have at least a couple of hotels and the main roads are sprinkled with campsites. If you have a tent and a well-insulated sleeping bag, you can, in theory, bed down more or less where you like, but the hostility of the climate and the ferocity of the summer mosquitoes, especially in the marshy areas of the Finnmarksvidda, make most people think (at least) twice. There are HI hostels at Alta, Karasjok, Kirkenes, Honningsvåg, Mehamn, Harstad, Senja, Skibotndalen and Tromsø.

ZODIAC EXCURSION ON ISFJORDEN, SVALBARD

Highlights

1 Emmas Drømmekjøkken, Tromsø Try the Arctic specialities – reindeer and char for instance – at this exquisite Tromsø restaurant.

2 Alta’s prehistoric rock carvings Follow the trail round northern Europe’s most extensive collection of prehistoric rock carvings.

3 Juhls’ Silver Gallery, Kautokeino The first and foremost of Finnmark’s Sámi-influenced jewellery-makers and designers.

4 Repvåg An old fishing station with traditional red-painted wooden buildings on stilts, framed by a picture-postcard setting.

5 The Hurtigruten Cruise around the tippity top of the European continent and across the Barents Sea – the most remote and spectacular section of this long-distance coastal boat trip.

6 End of the World Guesthouse Wonderful, charming new B&B set right out at the region’s most northerly stretches in laconic, iconic Gamvik.

7 Wildlife safaris on the Svalbard archipelago Take a snowmobile or Zodiac boat out in this remote archipelago to find over one hundred species of migratory birds as well as seals, walruses, whales, arctic foxes, reindeer and polar bears.

GETTING AROUND: NORTH NORWAY

Public transport in the provinces of Troms and Finnmark is by bus, the Hurtigruten coastal boat and plane – there are no trains to speak of. For all but the most truncated of tours, the best idea is to pick and mix these different forms of transport – for example by flying from Tromsø to Kirkenes and then taking the Hurtigruten back, or vice versa – in order to experience this part of Norway in as many ways as you can. What you should try to avoid is endless doubling-back on the E6, though this is often difficult as it is the only road to run right across the region. To give an idea of the distances involved, from Tromsø it’s 400km to Alta, 640km to Nordkapp and 970km to Kirkenes.

BY PLANE

Airports The region has several airports, including those at Alta, Hammerfest, Honningsvåg, Kirkenes, Tromsø and Longyearbyen, on Svalbard.

Airlines SAS (![]() flysas.com) and its

subsidiary, Widerøe (

flysas.com) and its

subsidiary, Widerøe (![]() wideroe.no), have the widest range of flights to northern

Norway – including a twice-daily route to and from Svalbard – but

Norwegian Airlines (

wideroe.no), have the widest range of flights to northern

Norway – including a twice-daily route to and from Svalbard – but

Norwegian Airlines (![]() norwegian.com) chips in too, flying regularly to Tromsø,

Alta, Kirkenes, Harstad/Narvik, Bardufoss and Lakselv.

norwegian.com) chips in too, flying regularly to Tromsø,

Alta, Kirkenes, Harstad/Narvik, Bardufoss and Lakselv.

Fares Standard return fares are usually expensive, but discounts are frequent and Norwegian Airlines are most economical.

BY BUS

Routes Torghatten Nord (![]() torghattennord.no) runs buses north from Bodø and Fauske

to Alta in three segments: Bodø to Narvik via Fauske (2 daily; 6hr

15min); Narvik to Tromsø (1–3 daily; 4hr 20min); and Tromsø to Alta

(1 daily; 6hr 30min). To get from Narvik to Alta you must change

buses at Balsfjord and then Nordkjosbotn. Passengers heading to

Nordkapp overnight at Alta, before proceeding on the next leg of the

journey north to Honningsvåg, where – from early June to late Aug –

they can change onto the connecting bus to Nordkapp. Alta is also

where you can pick up local buses to Hammerfest, Kautokeino,

Karasjok and Kirkenes.

torghattennord.no) runs buses north from Bodø and Fauske

to Alta in three segments: Bodø to Narvik via Fauske (2 daily; 6hr

15min); Narvik to Tromsø (1–3 daily; 4hr 20min); and Tromsø to Alta

(1 daily; 6hr 30min). To get from Narvik to Alta you must change

buses at Balsfjord and then Nordkjosbotn. Passengers heading to

Nordkapp overnight at Alta, before proceeding on the next leg of the

journey north to Honningsvåg, where – from early June to late Aug –

they can change onto the connecting bus to Nordkapp. Alta is also

where you can pick up local buses to Hammerfest, Kautokeino,

Karasjok and Kirkenes.

Timetables and tickets Bus timetables are available at most tourist offices and bus

stations; they are also available online – Nobina covers Tromsø and

its environs (![]() 177,

177, ![]() tromskortet.no) and

Boreal the whole of Finnmark (

tromskortet.no) and

Boreal the whole of Finnmark (![]() 177,

177, ![]() boreal.no). On the longer

rides, it’s a good idea to buy tickets in advance, or turn up early,

as buses fill up fast in the summer.

boreal.no). On the longer

rides, it’s a good idea to buy tickets in advance, or turn up early,

as buses fill up fast in the summer.

BY BOAT

Hurtigruten coastal boat A leisurely way to cross the region is on the daily Hurtigruten coastal boat

(![]() hurtigruten.no), which takes 40hr to cross the huge fjords

between Tromsø and Kirkenes. En route, it calls at eleven ports,

mostly remote fishing villages but also Hammerfest and Honningsvåg,

where northbound ferries pause for 4hr so that special buses can

cart passengers off to Nordkapp and back.

hurtigruten.no), which takes 40hr to cross the huge fjords

between Tromsø and Kirkenes. En route, it calls at eleven ports,

mostly remote fishing villages but also Hammerfest and Honningsvåg,

where northbound ferries pause for 4hr so that special buses can

cart passengers off to Nordkapp and back.

Car and boat travel One especially appealing option, though this has more to do with comfort than speed, is to travel by land and sea. Special deals on the Hurtigruten can make this surprisingly affordable and tourist offices at the Hurtigruten’s ports of call will make bookings. If you are renting a car, taking your vehicle onto the Hurtigruten may well work out a lot cheaper than leaving it at your port of embarkation: (see By car).

Hurtigbåt passenger express boat At the other end of the nautical extreme, the region has various Hurtigbåt passenger express boat services to some of the smaller settlements in Finnmark, as well as one main one between Tromsø and Harstad, which operates 3–4 times daily (twice at weekends).

BY CAR

Driving Though the E6 and some other main roads are kept open throughout the winter (as far as possible), conditions are not necessarily straightforward: drivers will find the going a little slow as they have to negotiate some pretty tough terrain, and ice and snow can make the roads treacherous, if not temporarily impassable, at any time. You can cover 250–300km in a day without any problem, but much more and it all becomes rather wearisome. Keep an eye on the fuel indicator too, as petrol stations are confined to the larger settlements and they may be 100–200km apart. Car repairs can take time since workshops are scarce and parts often have to be ordered from the south. Note also that if you are renting a car, one-way drop-off charges in Norway are invariably exorbitant, often exceeding 1000kr.

Summer Be warned that in July and August the E6 north of Alta can get congested with caravans and motorhomes on their way to Nordkapp. You can avoid the crush by starting early or, for that matter, by driving overnight – an eerie experience when it’s bright sunlight in the wee hours of the morning.

Winter If you’re not used to driving in winter conditions, don’t start here – especially during the polar night (late Nov to late Jan), which can be extremely disorientating. If you intend to use the region’s minor, unpaved roads, be prepared for the worst and take food and drink, warm clothes and a mobile phone.

Tromsø

Located at the northern end of the E8 some 260km north of Narvik, TROMSØ has been referred to, rather farcically, as the “Paris of the North”, and while even the tourist office doesn’t make any explicit pretence to such grandiose titles today, the city is without question the de facto social and cultural capital of northern Norway. Easily the region’s most populous town, its street cred harks back to the Middle Ages and beyond, when seafarers made use of its sheltered harbour, and there’s been a church here at least since the thirteenth century. Tromsø received its municipal charter in 1794, when it was primarily a fishing port and trading station, and flourished in the middle of the nineteenth century when its seamen ventured north to Svalbard to reap rich rewards hunting arctic fox, polar bears, reindeer, walrus and, most profitable of all, seal. Subsequently, Tromsø became famous as the jumping-off point for a string of Arctic expeditions, its celebrity status assured when the explorer Roald Amundsen flew from here to his death somewhere on the Arctic icecap in 1928. Since those heady days, Tromsø has grown into an urbane and likeable small city with a population of 68,000 employed in a wide range of industries and at the university. It’s become an important port too, for although the city is some 360km north of the Arctic Circle, its climate is moderated by the Gulf Stream, which sweeps up the Norwegian coast and keeps its harbour ice-free. Give or take the odd museum, the city may fall somewhat short on top-ranking sights, but its amiable atmosphere, fine mountain-and-fjord setting, and clutch of lively restaurants and bars more than compensate. Scenesters here remain extremely proud of locally grown electro-emo heroes Röyksopp, and the Tromsø’s DJ culture is consequently alive and kicking.

The compact centre slopes up from the eastern shores of the hilly island of Tromsøya, connected to the mainland by bridge and tunnel. A five-minute walk from one side to the other, the busiest part of the city centre spreads south from Stortorget, the main square, along Storgata, the main street and north–south axis, as far as Kirkegata and the harbourfront.

Domkirke

Kirkegata 7 • June–Aug Tues–Sat noon–4pm, Sun 10am–4pm; Sept–May Tues–Sat noon–4pm, Sun 10am–2pm • Free

Completed in 1861, the beige Lutheran Domkirke (Cathedral), bang in the centre on Kirkegata, bears witness to the prosperity of the town’s nineteenth-century merchants, who became rich on the back of the barter trade with Russia. They part-funded the cathedral’s construction, the result being the large and handsome structure of today, whose slender spire and dinky little tower pokes high into the sky above the neo-Gothic pointed windows of the nave. The building is now the only wooden cathedral in the country.

Nordnorsk Kunstmuseum

Sjøgata 1 • Mid-June to mid-Aug daily 11am–6pm; rest of year

Mon–Fri 10am–5pm, Sat & Sun noon–5pm • Free • ![]() nnkm.no

nnkm.no

In a sizeable old building a block east of the cathedral, the Nordnorsk Kunstmuseum (Art Museum of Northern Norway) is not a large ensemble, but the second-floor displays of the permanent collection were overhauled when the museum turned 25 in 2010, modernizing the place somewhat. The collection now covers all of Norway’s artistic bases, beginning in the nineteenth century with the ingenious landscapes of Thomas Fearnley and Johan Dahl and several Romantic peasant scenes by Adolph Tidemand (1814–76). There are lots of north Norway landscapes and seascapes here too, including several delightful paintings by Kongsberg-born Otto Sinding (1842–1909) – look out for his Spring Day in Lofoten – as well as a whole battery of paintings by the talented and prolific Axel Revold (1887–1962), whose work typically maintains a gentle, heart-warming lyricism. By contrast, Willi Midelfarts (1904–75) was clearly enraged when he painted his bloody Assault on the House of Karl Liebknecht, a reference to the murder of one of Germany’s leading Marxists in 1919. The museum also owns a handful of minor works by Edvard Munch, including a handsome portrait entitled Parisian Model.

Stortorget

The main square, Stortorget, is the site of a daily open-air market selling flowers and knick-knacks. The square nudges down towards the waterfront, where fresh fish and prawns are sold direct from inshore fishing boats throughout the summer.

Perspektivet Museum

Storgata 95 • June–Aug Tues–Sun 11am–5pm; Sept–May Tues–Fri

11am–3pm, Thurs till 7pm • Free • ![]() perspektivet.no

perspektivet.no

At the Perspektivet Museum the emphasis is on all things local, with a lively programme of temporary exhibitions concerning Tromsø and its inhabitants. In recent years, the museum has turned to focusing on its photographic collections – which now total some 400,000 images – even commissioning new works from local photographers to document the changing face of modern Tromsø. The building itself, dating from 1838, is also of interest as the one-time home of the local writer Cora Sandel (1880–1974), who was born Sara Fabricius and lived in Tromsø from 1893 to 1905, before shipping out to Paris. Sandel’s important works include the Alberte Trilogy, a set of semi-autobiographical novels following the trials and tribulations of a young woman as she attempts to establish her own independent identity. The museum has a small section on Sandel on the first floor, but it is confined to a few of her knick-knacks and several photos of her on walkabout in Tromsø.

Polarmuseet

Søndre Tollbodgate 11 • Daily: March to mid-June & mid-Aug to Sept

11am–5pm; mid-June to mid-Aug 10am–7pm; Oct–Feb 11am–4pm • 50kr • ![]() polarmuseum.no

polarmuseum.no

Down by the water, an old wooden warehouse holds the city’s most engaging museum, the Polarmuseet (Polar Museum). The collection begins with a less-than-stimulating series of displays on trapping in the Arctic, but beyond is an outstanding section on Svalbard, including archeological finds retrieved in the 1980s from an eighteenth-century Russian whaling station. Most of the artefacts come from graves preserved by permafrost and, among many items, there are combs, leather boots, parts of a sledge, slippers and even – just to prove illicit puffing is not a recent phenomenon – a clay pipe from a period when the Russian company in charge of affairs forbade trappers from smoking. Two other sections on the first floor focus on seal hunting, an important part of the local economy until the 1950s.

Upstairs, on the second floor, a further section is devoted to the exploits of one Henry Rudi (1889–1970), the so-called “Isbjørnkongen” (Polar Bear King), who spent 27 winters on Svalbard and Greenland, bludgeoning his way through the local wildlife, killing 713 polar bears in the process. Rather more edifying is the extensive display on the polar explorer Roald Amundsen (1872–1928), who spent thirty years searching out the secrets of the polar regions. The museum exhibits all sorts of oddments used by Amundsen and his men – from long johns and pipes through to boots and ice picks – but it is the photos that steal the show, providing a fascinating insight into the way Amundsen’s polar expeditions were organized and the hardships he and his men endured. Amundsen clearly liked having his picture taken, judging from the heroic poses he struck, his derring-do emphasized by the finest set of eyebrows north of Oslo.

Finally, there’s another extensive section on Amundsen’s contemporary Fridtjof Nansen (1861–1930), a polar explorer of similar renown who, in his later years, became a leading figure in international famine relief. In 1895, Nansen and his colleague Hjalmar Johansen made an abortive effort to reach the North Pole by dog sledge after their ship was trapped by pack ice. It took them a full fifteen months to get back to safety, a journey of such epic proportions that tales of it captivated all of Scandinavia.

ROALD AMUNDSEN

One of Norway’s most celebrated sons, Roald Amundsen (1872–1928) was intent on becoming a polar explorer from his early teens. He read everything there was to read on the subject, even training as a sea captain in preparation, and, in 1897, embarked with a Belgian expedition upon his first trip to Antarctica. Undeterred by a winter on the ice after the ship broke up, he was soon planning his own expedition. In 1901, he purchased a sealer, the Gjøa, in Tromsø, leaving in June 1903 to spend three years sailing and charting the Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and the Pacific. The Gjøa (now on display in Oslo) was the first vessel to complete this extraordinary voyage, which tested Amundsen and his crew to the very limits. Long searched for, the Passage had for centuries been something of a nautical Holy Grail and the voyage’s progress – and at times the lack of it – was headline news right across the world.

Amundsen’s next target was the North Pole, but during his preparations, in 1909, the American admiral and explorer Robert Peary got there first. Amundsen immediately switched his attention to the South Pole, and in 1910 set out in a new ship, the Fram (also exhibited in Oslo), for the Antarctic, which he reached on December 14, 1911, famously beating the British expedition of Captain Scott by just a couple of weeks.

Neither did Amundsen’s ambitions end there: in 1926, he became one of the first men to fly over the North Pole in the airship of the Italian Umberto Nobile, though it was this last expedition that did for Amundsen: in 1928, the Norwegian flew north out of Tromsø in a bid to rescue the stranded Nobile and was never seen again.

Tromsø Kunstforening

Musegata 2 • Wed–Sun noon–5pm • Free • ![]() tromsokunstforening.no

tromsokunstforening.no

Just to the south of the town centre, at the upper end of Muségata, the Tromsø Kunstforening (Tromsø Art Society) occupies part of a large and attractive Neoclassical building dating from the 1890s. The cultural organization puts on imaginative temporary exhibitions of Norwegian contemporary art with the emphasis on the work of northern Norwegian artists.

Polaria

Hjalmar Johansens gate 12 • Daily: mid-May to mid-Aug 10am–7pm; mid-Aug to

mid-May 11am–5pm • 105kr • ![]() polaria.no • The complex is 200m south of Tromsø

Kunstforening along Storgata

polaria.no • The complex is 200m south of Tromsø

Kunstforening along Storgata

A lavish waterfront complex, Polaria deals with all things Arctic. There’s an aquarium filled with Arctic species, a 180-degree cinema showing a film on Svalbard shot from a helicopter and several exhibitions on polar research. Parked outside in a glass greenhouse is a 1940s sealing ship, the M/S Polstjerna.

Arktisk-alpin botanisk hage

Breivika • Year-round dawn to dusk • Free • ![]() uit.no/botanisk • Bus #42

uit.no/botanisk • Bus #42

Located next to the University of Tromsø’s Breivika campus in the centre of the island 4km north of the centre, the Arktisk-alpin botanisk hage (Arctic-Alpine Botanical Gardens) are the world’s most northerly botanical gardens, spanning some five acres of land. There are plants from all continents, with particular strong representation from Siberia, the Himalayas and the Rockies; they all tend to bloom from May to October.

Tromsø Museum

Lars Thørings veg 10 • June–Aug daily 9am–6pm; rest of year Mon–Fri

9am–4.30pm, Sat noon–3pm, Sun 11am–4pm • 30kr • ![]() uit.no/tmu • Bus #37 from the centre (every 30min;

uit.no/tmu • Bus #37 from the centre (every 30min; ![]() nobina.no)

nobina.no)

About 3km south of the centre, near the southern tip of Tromsøya, the Tromsø Museum is a historical and ethnographic museum run by the university. It’s a varied collection, featuring nature and the sciences downstairs, and culture and history above. Pride of place goes to the medieval religious carvings, naïve but evocative pieces retrieved from various northern Norwegian churches. There’s also an enjoyable section on the Sámi featuring displays on every aspect of Sámi life – from dwellings, tools and equipment through to traditional costume and hunting techniques. Meanwhile, the aurora borealis exhibit gives a particularly good explanation on exactly why and how the phenomenon exists.

Ishavskatedralen

Hans Nilsens veg 41 • Mid- to late May daily 3–6pm; June to mid-Aug

Mon–Sat 9am–7pm, Sun 1–7pm; mid-Aug to mid-May daily 3/4–6pm • 35kr • ![]() ishavskatedralen.no • Bus #20, #24 or #28

ishavskatedralen.no • Bus #20, #24 or #28

A few minutes’ walk east from the centre, across the spindly, cantilevered Tromsøbrua bridge, rises the desperately modern Ishavskatedralen (Arctic Cathedral). Completed in 1965 – and recently renovated – the church maintains a strikingly white, glacier-like appearance, achieved by means of eleven immense triangular concrete sections, representing the eleven Apostles left after the betrayal. The entire east wall is formed by a huge stained-glass window, one of the largest in Europe, and the organ is unusual too, built to represent a ship when viewed from beneath – recalling the tradition, still seen in many a Nordic church, of suspending a ship from the ceiling as a good-luck talisman for seafarers.

ARCTIC PHENOMENA

On and above the Arctic Circle, an imaginary line drawn round the earth at latitude 66.5 degrees north, there is a period around midsummer during which the sun never makes it below the horizon, even at midnight – hence the midnight sun. On the Arctic Circle itself, this only happens on one night of the year – at the summer solstice – but the further north you go, the greater the number of nights without darkness: in Bodø, it’s from the first week of June to early July; in Tromsø from late May to late July; in Alta, from the third week in May to the end of July; in Hammerfest, mid-May to late July; and in Nordkapp, early May to the end of July. Obviously, the midnight sun is best experienced on a clear night, but fog or cloud can turn the sun into a glowing, red ball – a spectacle that can be wonderful but also strangely uncanny. All the region’s tourist offices have the exact dates of the midnight sun, though note that these are calculated at sea level; climb up a hill and you can extend the dates by a day or two. The converse of all this is the polar night, a period of constant darkness either side of the winter solstice; again the further north of the Arctic Circle you are, the longer this lasts.

The Arctic Circle also marks the typical southern limit of the northern lights, or aurora borealis, though this extraordinary phenomenon has been seen as far south as latitude 40 degrees north – roughly the position of New York or Ankara. Caused by the bombardment of the atmosphere by electrons, carried away from the sun by the solar wind, the northern lights take various forms and are highly mobile – either flickering in one spot or travelling across the sky. At relatively low latitudes hereabouts, the aurora is tilted at an angle and is often coloured red – the sagas tell of Vikings being half scared to death by them – but nearer the pole, they hang like gigantic luminous curtains, often tinted greenish blue. Naturally enough, there’s no predicting when the northern lights will occur. They are most likely to come out during the darkest period (between November and February) – though they can be seen as early as late August and as late as mid-April. On a clear night the fiery ribbons can be strangely humbling.

Fjellheisen mountain funicular

Daily every 30min: Feb & March 10am–4pm;

April to late May & Sept 10am–5pm; late May to early Aug 10am–1am;

Aug 10am–10pm; Oct–Dec 1am–4pm; • 120kr • ![]() fjellheisen.no • Bus #26 from the city centre or a 15min walk

southeast of the Ishavskatedralen

fjellheisen.no • Bus #26 from the city centre or a 15min walk

southeast of the Ishavskatedralen

Every half-hour the Fjellheisen mountain funicular, 3km from the centre across the bridge, whisks up to 27 passengers up to the top of Mount Storsteinen. From the 421m summit, the views of the city and its surroundings are extensive and it’s a smashing spot to catch the midnight sun; there’s even a café at the top. Note that mountain funicular services are suspended during inclement weather.

ARRIVAL AND DEPARTURE: TROMSØ

By plane The airport is 5km west of the centre on the other side of Tromsøya. Frequent Flybussen (Mon–Fri 5.30am–midnight every 15min–1hr, Sat 5.30am–4.40pm roughly hourly, Sun 10.20am–midnight hourly; 60kr) run into the city, stopping at the Rica Ishavshotel on Sjøgata and at most central hotels. A taxi to the centre will cost between 120–150kr.

By bus Long-distance buses pull in at the stops on Prostneset, metres

from the Hurtigruten quay. Torghatten (![]() tromskortet.no)

services run to Alta (1–2 daily; 6hr 30min) and Narvik (2–4 daily;

4hr 15min).

tromskortet.no)

services run to Alta (1–2 daily; 6hr 30min) and Narvik (2–4 daily;

4hr 15min).

By boat The Hurtigruten coastal boat (![]() hurtigruten.com) docks

in the town centre beside the Prostneset quay at the foot of

Kirkegata, while Hurtigbåt services (

hurtigruten.com) docks

in the town centre beside the Prostneset quay at the foot of

Kirkegata, while Hurtigbåt services (![]() tromskortet.no) arrive

at the jetty about 150m to the south. Northbound, the Hurtigruten

leaves Tromsø for Hammerfest daily at 6.30pm (11hr); southbound it

sails at 1.30am, arriving in Harstad 6hr 30min later. The main

Hurtigbåt passenger express boat service, meanwhile, links Tromsø

with Harstad (2–5 daily; 2hr 45min). For Lofoten, it’s quickest and

easiest if you take the Hurtigbåt to Harstad, then the bus.

tromskortet.no) arrive

at the jetty about 150m to the south. Northbound, the Hurtigruten

leaves Tromsø for Hammerfest daily at 6.30pm (11hr); southbound it

sails at 1.30am, arriving in Harstad 6hr 30min later. The main

Hurtigbåt passenger express boat service, meanwhile, links Tromsø

with Harstad (2–5 daily; 2hr 45min). For Lofoten, it’s quickest and

easiest if you take the Hurtigbåt to Harstad, then the bus.

By car Cars in Tromsø can be rented from Europcar, Alkeveien 5, and at

the airport (![]() 77 67 56 00); Hertz, Fridtjof

Nansenplass 3c, and at the airport (

77 67 56 00); Hertz, Fridtjof

Nansenplass 3c, and at the airport (![]() 48 26 20

00).

48 26 20

00).

GETTING AROUND

By bus For Tromsø’s outlying attractions you’ll need to catch a municipal

bus (![]() 177,

177, ![]() tromskortet.no). The standard, flat-rate fare is

28kr.

tromskortet.no). The standard, flat-rate fare is

28kr.

By taxi Tromsø Taxi ![]() 77 60 30 10 (24hr).

77 60 30 10 (24hr).

By bike Bikes can be rented from Tromsø Natur og Fritid, Sjøgata 14 (![]() tromsonaturogfritid.no), which has touring cycles from

230kr/day.

tromsonaturogfritid.no), which has touring cycles from

230kr/day.

INFORMATION

Tourist office Kirkegata 2, a few paces from the Prostneset quay (mid-May to Aug

Mon–Fri 9am–7pm, Sat & Sun 10am–4pm; rest of year Mon–Fri

9am–4pm, Sat 10am–4pm, plus Jan & Feb Sun 11am–3.30pm; ![]() 77

61 00 00,

77

61 00 00, ![]() visittromso.no). It issues free town maps, has a small

list of B&Bs, and provides oodles of local information,

including details of bus and boat sightseeing trips around

neighbouring islands.

visittromso.no). It issues free town maps, has a small

list of B&Bs, and provides oodles of local information,

including details of bus and boat sightseeing trips around

neighbouring islands.

OUTDOOR ACTIVITIES

Diving and sea rafting Dykkersenteret AS, Stakkevollveien 72 (![]() 77 69 66 00,

77 69 66 00,

![]() dykkersentret.no), organizes guided diving tours to local

wrecks in the surrounding fjords. Also runs fishing and midnight-sun

excursions and offers equipment rental.

dykkersentret.no), organizes guided diving tours to local

wrecks in the surrounding fjords. Also runs fishing and midnight-sun

excursions and offers equipment rental.

Hiking Troms Turlag, next door to the tourist office at Kirkegata 2 (Wed

noon–4pm, Thurs noon–6pm, Fri noon–2pm; ![]() 77 68 51 75,

77 68 51 75,

![]() turistforeningen.no/troms), is a DNT affiliate with bags

of information on local hiking trails and DNT huts.

turistforeningen.no/troms), is a DNT affiliate with bags

of information on local hiking trails and DNT huts.

Wilderness tours Among several wilderness-tour specialists, Tromsø Villmarkssenter

(Tromsø Wilderness Centre; ![]() 77 69 60 02,

77 69 60 02, ![]() villmarkssenter.no)

offers a wide range of activities from guided glacier walks, kayak

paddling and mountain climbing in summer to ski trips and dog-sled

rides in winter. Overnight trips staying in a lavvo (a Sámi tent) can also be arranged. It is run by

Tove Sorensen and Tore Albrigsten – and their several hundred

Alaskan huskies – Norway’s most experienced dog-sled racers. The

centre is located about 6km from downtown Tromsø at Straumsvegen

603, beyond the airport on the island of Kvaløya.

villmarkssenter.no)

offers a wide range of activities from guided glacier walks, kayak

paddling and mountain climbing in summer to ski trips and dog-sled

rides in winter. Overnight trips staying in a lavvo (a Sámi tent) can also be arranged. It is run by

Tove Sorensen and Tore Albrigsten – and their several hundred

Alaskan huskies – Norway’s most experienced dog-sled racers. The

centre is located about 6km from downtown Tromsø at Straumsvegen

603, beyond the airport on the island of Kvaløya.

ACCOMMODATION

Tromsø has a good supply of modern, central hotels, though the majority occupy chunky concrete high-rises whose exterior may or may not be indicative of what lies await inside. Less expensive – and sometimes more distinctive – are the town’s guesthouses; there’s also a rudimentary HI hostel. In addition, the tourist office has a small list of B&Bs, but most are stuck out in the suburbs. Tromsø is a popular destination, so advance reservation is recommended, especially in the summer.

HOTELS

ABC Hotel Nord Parkgata 4 ![]() 77 66 83 00,

77 66 83 00, ![]() hotellnord.no.

Though Tromsø no longer has an HI hostel, this budget hotel is

aimed at backpackers and students (with discounts for the

latter), and offers an unbeatable central location three blocks

west of the cathedral on Storgata. Rooms feature free calls to

Norwegian landlines, and there is free parking and use of the

well-appointed kitchen. Cycle rental 150kr/day. 875kr

hotellnord.no.

Though Tromsø no longer has an HI hostel, this budget hotel is

aimed at backpackers and students (with discounts for the

latter), and offers an unbeatable central location three blocks

west of the cathedral on Storgata. Rooms feature free calls to

Norwegian landlines, and there is free parking and use of the

well-appointed kitchen. Cycle rental 150kr/day. 875kr

Ami Skolegata 24 ![]() 77 62 10 00,

77 62 10 00, ![]() amihotel.no.

With seventeen simple rooms offering significantly more style

than other spots in this price range, this guesthouse/hotel is

set in a period wooden villa behind the town centre and offers

wide views over the city from the hillside. Wi-fi access and

breakfast included in price. 750kr

amihotel.no.

With seventeen simple rooms offering significantly more style

than other spots in this price range, this guesthouse/hotel is

set in a period wooden villa behind the town centre and offers

wide views over the city from the hillside. Wi-fi access and

breakfast included in price. 750kr

Quality Hotel Saga Richard Withsplass 2 ![]() 77 60 70 00,

77 60 70 00, ![]() choicehotels.no.

Although there has been some Ikea-ization at this mid-sized,

1960s chain hotel, renovated in 2010, the public areas remain

reassuringly old-fashioned with lots of pine (rather than

chipboard), while most of the 103 rooms have at least a bit of

pizzazz. Ask for a room on a high floor for views right onto the

Domkirke. Set smack in the centre of town. 1295kr

choicehotels.no.

Although there has been some Ikea-ization at this mid-sized,

1960s chain hotel, renovated in 2010, the public areas remain

reassuringly old-fashioned with lots of pine (rather than

chipboard), while most of the 103 rooms have at least a bit of

pizzazz. Ask for a room on a high floor for views right onto the

Domkirke. Set smack in the centre of town. 1295kr

Radisson Blu Hotel Tromsø Sjøgata 7 ![]() 77 60 00 00,

77 60 00 00, ![]() radissonblu.com.

The largest hotel in town – and a very popular one – occupying

two large ten-storey towers at the harbour. The rooms, which had

a refit a few years ago, have been kitted out in two styles,

Arctic (calming white, orange and green finishes) and Chilli

(somewhat warmer red tones); the Superior ones (as well as the

gym and sauna) have cracking views of the harbour.

Ultra-efficient service, and free wi-fi to boot. Downstairs is

the lively and well-known (to Norwegians, at least) Rorbua pub, which occasionally features

live music. 1195kr

radissonblu.com.

The largest hotel in town – and a very popular one – occupying

two large ten-storey towers at the harbour. The rooms, which had

a refit a few years ago, have been kitted out in two styles,

Arctic (calming white, orange and green finishes) and Chilli

(somewhat warmer red tones); the Superior ones (as well as the

gym and sauna) have cracking views of the harbour.

Ultra-efficient service, and free wi-fi to boot. Downstairs is

the lively and well-known (to Norwegians, at least) Rorbua pub, which occasionally features

live music. 1195kr

Rica Ishavshotel Tromsø Fr. Langes gate 2

Rica Ishavshotel Tromsø Fr. Langes gate 2 ![]() 77 66 64 00,

77 66 64 00, ![]() rica.no.

Perched on the harbourfront a few metres from the Hurtigruten

dock, this imaginatively designed hotel is partly built in the

style of a ship, complete with a sort of crow’s-nest bar. Lovely

rooms – half of them are singles, thanks to such a big trade in

business travellers here – and unbeatable views over the harbour

with the mountains glinting behind make it the best setting in

town. Fourth-floor bar has some breathtaking views. 1495kr

rica.no.

Perched on the harbourfront a few metres from the Hurtigruten

dock, this imaginatively designed hotel is partly built in the

style of a ship, complete with a sort of crow’s-nest bar. Lovely

rooms – half of them are singles, thanks to such a big trade in

business travellers here – and unbeatable views over the harbour

with the mountains glinting behind make it the best setting in

town. Fourth-floor bar has some breathtaking views. 1495kr

Viking Grønnegata 18 ![]() 77 64 77 30,

77 64 77 30, ![]() viking-hotell.no.

The 24 bright and modern rooms at this breezy guesthouse have

considerably more energy than most other places in town. They

also have several contemporary apartment-style rooms with full

kitchens and large living spaces. Centrally located near the

Mack brewery. 980kr

viking-hotell.no.

The 24 bright and modern rooms at this breezy guesthouse have

considerably more energy than most other places in town. They

also have several contemporary apartment-style rooms with full

kitchens and large living spaces. Centrally located near the

Mack brewery. 980kr

CAMPSITE

Tromsø Camping Elvestrandvegen ![]() 77 63 80 37,

77 63 80 37, ![]() tromsocamping.no.

Reasonably handy waterside site about 2km east of the Arctic

Cathedral (Ishavskatedralen), on the mainland side of the main

bridge, with 55 modern and “rustic” cabins. Open year-round.

Take bus #20 or #24. Cabins from 1049kr, tent pitches

for two people from 130kr

tromsocamping.no.

Reasonably handy waterside site about 2km east of the Arctic

Cathedral (Ishavskatedralen), on the mainland side of the main

bridge, with 55 modern and “rustic” cabins. Open year-round.

Take bus #20 or #24. Cabins from 1049kr, tent pitches

for two people from 130kr

EATING, DRINKING AND NIGHTLIFE

With a clutch of first-rate restaurants, several enjoyable cafés and a great supply of late-night bars, Tromsø is at least as well served as any comparably sized Norwegian city. The best of the cafés and restaurants are concentrated in the vicinity of the Domkirke, and most of the livelier bars – many of which sell Mack, the local brew – are in the centre, too.

CAFÉS AND RESTAURANTS

Arctandria Strandtorget 1

Arctandria Strandtorget 1 ![]() 77 60 07 20,

77 60 07 20, ![]() skarven.no.

Some of the best food in town. The upstairs restaurant serves a

superb range of fish, with the emphasis on Arctic species, and

there’s also reindeer, whale and seal; main courses start at

around 245kr (or 195kr if you’re going vegetarian). If you’ve

come on an empty stomach, try their five-course Mack Menu

(595kr), with every course cooked in some capacity with local

beer. Prices are somewhat cheaper downstairs at the café-bar

Vertshuset Skarven, where there’s

a slightly less varied menu.

Mon–Sat 4pm–midnight.

skarven.no.

Some of the best food in town. The upstairs restaurant serves a

superb range of fish, with the emphasis on Arctic species, and

there’s also reindeer, whale and seal; main courses start at

around 245kr (or 195kr if you’re going vegetarian). If you’ve

come on an empty stomach, try their five-course Mack Menu

(595kr), with every course cooked in some capacity with local

beer. Prices are somewhat cheaper downstairs at the café-bar

Vertshuset Skarven, where there’s

a slightly less varied menu.

Mon–Sat 4pm–midnight.

Aunegården Sjøgata 29 ![]() 77 65 12 34

77 65 12 34 ![]() aunegarden.no.

Cosy and popular café-restaurant within the listed late

nineteenth-century Aunegården building, which was set up as a

butcher in 1830. All the standard Norwegian dishes are served,

including stockfish, at moderate prices (mains 108–157kr), and

the triad of rather more controversial dishes – whale, seal and

shark – also make an appearance. Still, these are nothing when

compared with the cakes – wonderful confections, which are made

at their own bakery. Weep with pleasure as you nibble at the

cheesecake – then weep with pain as you realize that pleasure

just cost you a dear 69kr.

Mon–Sat 10.30am–11pm, Sun noon–6pm.

aunegarden.no.

Cosy and popular café-restaurant within the listed late

nineteenth-century Aunegården building, which was set up as a

butcher in 1830. All the standard Norwegian dishes are served,

including stockfish, at moderate prices (mains 108–157kr), and

the triad of rather more controversial dishes – whale, seal and

shark – also make an appearance. Still, these are nothing when

compared with the cakes – wonderful confections, which are made

at their own bakery. Weep with pleasure as you nibble at the

cheesecake – then weep with pain as you realize that pleasure

just cost you a dear 69kr.

Mon–Sat 10.30am–11pm, Sun noon–6pm.

Emmas Drømmekjøkken Kirkegata 8

Emmas Drømmekjøkken Kirkegata 8 ![]() 77 63 77 30,

77 63 77 30, ![]() www.emmasdrommekjokken.no.

Much praised in the national press as a gourmet treat, “Emma’s

dream kitchen” lives up to its name, with an imaginative and

wide-ranging menu focused on Norwegian produce. The grilled

arctic char with gorgonzola sauce and cowberries is a treat as

is the delicious Tana reindeer fillet with port sauce and

roasted garlic. Excellent service in smart premises. Main

courses are 335kr and up. Reservations recommended.

Mon–Sat from 6pm; closed Sun.

www.emmasdrommekjokken.no.

Much praised in the national press as a gourmet treat, “Emma’s

dream kitchen” lives up to its name, with an imaginative and

wide-ranging menu focused on Norwegian produce. The grilled

arctic char with gorgonzola sauce and cowberries is a treat as

is the delicious Tana reindeer fillet with port sauce and

roasted garlic. Excellent service in smart premises. Main

courses are 335kr and up. Reservations recommended.

Mon–Sat from 6pm; closed Sun.

Thai House Storgata 22 ![]() 77 67 05 26,

77 67 05 26, ![]() thaihouse.no.

Decent Thai cooking with the welcome inclusion of some excellent

fish and vegetable dishes; the Thai spicy salads are especially

good, as are the soups, though prices aren’t cheap, with mains

from around 220kr).

Daily noon–11pm.

thaihouse.no.

Decent Thai cooking with the welcome inclusion of some excellent

fish and vegetable dishes; the Thai spicy salads are especially

good, as are the soups, though prices aren’t cheap, with mains

from around 220kr).

Daily noon–11pm.

BARS

Amundsen Restauranthus Storgata 42 ![]() 77 68 52 34,

77 68 52 34, ![]() arh.no.

Named after the Norwegian explorer who stayed in this building

when he lived in Tromsø, this trendy, colourfully decorated bar

is Tromsø’s most gay-friendly nightspot.

Mon 3pm–midnight, Tues–Thurs 1pm–1.30am, Fri & Sat 11am–3am, Sun 3–11pm.

arh.no.

Named after the Norwegian explorer who stayed in this building

when he lived in Tromsø, this trendy, colourfully decorated bar

is Tromsø’s most gay-friendly nightspot.

Mon 3pm–midnight, Tues–Thurs 1pm–1.30am, Fri & Sat 11am–3am, Sun 3–11pm.

Blå Rock Café Strandgata 14 ![]() 77 61 00 20,

77 61 00 20, ![]() blarock.no.

Definitely the place to go for loud rock music. Also features

regular live acts, plus the best burgers in town (try the

amazing blue-cheese Astroburger). They serve several dozen

beers, most priced at around 60kr.

Mon–Thurs 11.30am–2am, Fri & Sat 11.30am–3.30am, Sun 1pm–2am.

blarock.no.

Definitely the place to go for loud rock music. Also features

regular live acts, plus the best burgers in town (try the

amazing blue-cheese Astroburger). They serve several dozen

beers, most priced at around 60kr.

Mon–Thurs 11.30am–2am, Fri & Sat 11.30am–3.30am, Sun 1pm–2am.

Ølhallen Pub Storgata 4 ![]() 77 62 45 80,

77 62 45 80, ![]() olhallen.no.

Solid (some might say stolid) basement pub adjoining the Mack

brewery, whose various ales are its speciality. It’s the first

pub in town to start serving – and the earliest to close – and

so only pulls in the serious drinkers.

Mon–Thurs 9am–5pm, Fri 9am–6pm, Sat 9am–3pm.

olhallen.no.

Solid (some might say stolid) basement pub adjoining the Mack

brewery, whose various ales are its speciality. It’s the first

pub in town to start serving – and the earliest to close – and

so only pulls in the serious drinkers.

Mon–Thurs 9am–5pm, Fri 9am–6pm, Sat 9am–3pm.

Rorbua Pub Søren Fløttmanns plass ![]() 77 75 90 86,

77 75 90 86, ![]() rorbuapub.no.

Known all over the country thanks to its long-time home as a

popular weekly talk show, Du skal høre

mye (“You’ll Hear a Lot”). Presided over by a

mammoth stuffed polar bear, this timbered spot calls to mind a

drunken fisherman’s cabin from times of yore.

rorbuapub.no.

Known all over the country thanks to its long-time home as a

popular weekly talk show, Du skal høre

mye (“You’ll Hear a Lot”). Presided over by a

mammoth stuffed polar bear, this timbered spot calls to mind a

drunken fisherman’s cabin from times of yore.

Skipsbroen Rica Ishavshotel, Fr. Langes gate 2 ![]() 77 66 64 00,

77 66 64 00, ![]() rica.no.

Inside the Rica Ishavshotel, this smart little bar overlooks the

waterfront from on high – it occupies the top of a slender tower

with wide windows and sea views. Relaxed atmosphere but lots of

tourists.

Mon–Thurs 6pm–1.30am, Fri & Sat 3pm–3am; closed Sun.

rica.no.

Inside the Rica Ishavshotel, this smart little bar overlooks the

waterfront from on high – it occupies the top of a slender tower

with wide windows and sea views. Relaxed atmosphere but lots of

tourists.

Mon–Thurs 6pm–1.30am, Fri & Sat 3pm–3am; closed Sun.

Studenthuset Driv Søndre Tollbodgate 3b ![]() 77 60 07 76,

77 60 07 76, ![]() driv.no.

Built in the early 1900s as a fisherman’s warehouse, and now

dining out on its exposed beams and planking, this three-tiered

student hangout never wants for its share of barflies. Wed &

Thurs there are live concerts (cover from 30–160kr), while Fri

& Sat the disco (cover 40kr) crowd takes over. Come early to

snag a seat on the benches outside; come late to watch the

pick-up games begin.

Mon–Thurs noon–2am, Fri & Sat noon–3.30am.

driv.no.

Built in the early 1900s as a fisherman’s warehouse, and now

dining out on its exposed beams and planking, this three-tiered

student hangout never wants for its share of barflies. Wed &

Thurs there are live concerts (cover from 30–160kr), while Fri

& Sat the disco (cover 40kr) crowd takes over. Come early to

snag a seat on the benches outside; come late to watch the

pick-up games begin.

Mon–Thurs noon–2am, Fri & Sat noon–3.30am.

ENTERTAINMENT

Kino Fokus ![]() 90 88 99 00,

90 88 99 00, ![]() tromsokino.no.

The main cinema is where you’ll find many students and sober

locals looking to catch up on some culture. They tend to feature

Hollywood box office hits side by side with a surprising number

of domestically produced cinematic fare. The odd European

art-house flick is added in from time to time for good

measure.

tromsokino.no.

The main cinema is where you’ll find many students and sober

locals looking to catch up on some culture. They tend to feature

Hollywood box office hits side by side with a surprising number

of domestically produced cinematic fare. The odd European

art-house flick is added in from time to time for good

measure.

Kulturhuset Erling Bangsunds plass 1 ![]() 77 79 16 66,

77 79 16 66, ![]() kulturhuset.tr.no.

The principal venue for cultural events of all kinds, this large

space beside Grønnegata tends to focus on live Nordic music

groups, though there are also touring dance troupes and the odd

musical revue as well.

kulturhuset.tr.no.

The principal venue for cultural events of all kinds, this large

space beside Grønnegata tends to focus on live Nordic music

groups, though there are also touring dance troupes and the odd

musical revue as well.

SHOPPING

Bokhuset Libris Storgata 86 ![]() 77 68 30 36,

77 68 30 36, ![]() libris.no.

Hardly the biggest bookshop in Norway, but this family-owed

franchise of the big chain is Tromsø’s best, with a very good

selection of English-language publications.

Mon–Thurs 9am–6pm, Fri 9am–4.30pm, Sat 10am–4pm.

libris.no.

Hardly the biggest bookshop in Norway, but this family-owed

franchise of the big chain is Tromsø’s best, with a very good

selection of English-language publications.

Mon–Thurs 9am–6pm, Fri 9am–4.30pm, Sat 10am–4pm.

Vinmonopolet Grønnegata 64. Effectively the only place in town to pick up hard liquor; also stocks Tromsø’s largest selection of wines. Mon–Fri 10am–6pm, Sat 10am–3pm.

DIRECTORY

Internet Free access at Tromsø Bibliotek, on Grønnegata near Stortorget (Mon–Thurs 9am–7pm, Fri 9am–5pm, Sat 11am–3pm, Sun noon–4pm).

Pharmacy Vitusapotek Svanen, opposite the Radisson SAS Hotel at Fr. Langes gate 9 (Mon–Fri 8.30am–4.30pm, Sat 10am–2pm).

Post office Main office at Strandgata 41 (Mon–Fri 8am–6pm, Sat 10am–3pm).

West from Tromsø: Kvaløya and Sommarøy

Heading west from Tromsø towards Andenes, Highway 862 crosses the Sandnessundet straits to reach the mountainous island of Kvaløya, whose three distinct parts are joined by a couple of narrow isthmuses. On the far side of the straits, the highway meanders south offering lovely fjord and mountain views en route to the Brensholmen–Botnhamn car ferry, about 60km from Tromsø. From Botnhamn, it’s a further 160km to Gryllefjord, where a second car ferry takes you across to Andenes on Vesterålen. The pretty route makes a great little journey in itself, and breaking up the trip on the tiny islet of Sommarøy, linked to Kvaløya by a causeway that branches off Highway 862 a few kilometres short of Brensholmen, is a good option, where you can stay at a fetching little waterside hytte at the Sommarøy Arctic Hotel, then hop into one of their wooden outdoor hot-tubs for a Nordic jacuzzi session.

ARRIVAL AND DEPARTURE: WEST FROM TROMSØ: KVALØYA AND SOMMARØY

Car ferries Senjafergene (![]() 99 48 57 50,

99 48 57 50, ![]() senjafergene.no)

operate the Brensholmen–Botnhamn (May–Aug 5–7 daily; 45min) and

Gryllefjord–Andenes (late May to mid-June & mid- to late Aug 2

daily; mid-June to early Aug 3 daily; 1hr 40min; reservations

advised) car ferries.

senjafergene.no)

operate the Brensholmen–Botnhamn (May–Aug 5–7 daily; 45min) and

Gryllefjord–Andenes (late May to mid-June & mid- to late Aug 2

daily; mid-June to early Aug 3 daily; 1hr 40min; reservations

advised) car ferries.

ACCOMMODATION AND EATING

Sommarøy Arctic Hotel Sommarøy ![]() 77 66 40 00,

77 66 40 00, ![]() sommaroy.no.

This relaxing hotel offers accommodation in the main building, plus

high-quality, well-equipped seashore cabins for up to ten people

(2600kr/day). The restaurant is excellent too, particularly its

Arctic specialities, and there are two traditional badestamp – wooden hot-tubs seating up to ten people –

one inside and one outdoors, next to the ocean. Rooms 1090kr,

six-berth cabins 1590kr

sommaroy.no.

This relaxing hotel offers accommodation in the main building, plus

high-quality, well-equipped seashore cabins for up to ten people

(2600kr/day). The restaurant is excellent too, particularly its

Arctic specialities, and there are two traditional badestamp – wooden hot-tubs seating up to ten people –

one inside and one outdoors, next to the ocean. Rooms 1090kr,

six-berth cabins 1590kr

The road to Finnmark

Beyond Tromsø, the vast sweep of the northern landscape slowly unfolds, with silent fjords cutting deep into the coastline beneath ice-tipped peaks which themselves fade into the high plateau of the interior. This forbidding, elemental terrain is interrupted by the occasional valley, where those few souls hardy enough to make a living in these parts struggle on – often subsisting by dairy farming. Curiously enough, one particular problem for the farmers here has been the abundance of Siberian garlic (Allium sibiricum): the cows love the stuff – it tastes much more like a chive than garlic – but if they eat a lot of it, the milk they produce tastes of onions.

Slipping along the valleys and traversing the mountains in between, the E8 and then the E6 follow the coast pretty much all the way from Tromsø to Alta, some 410km – and about a seven-hour drive – to the north. Drivers can save around 100km (although not necessarily time and certainly not money) by turning off the E8 25km south of Tromsø onto Highway 91 – a quieter, even more scenic route, offering extravagant fjord and mountain views. Highway 91 begins by cutting across the rocky peninsula that backs onto Tromsø to reach the Breivikeidet–Svensby car ferry, a magnificent twenty-minute journey over to the glaciated Lyngen peninsula. From the Svendsby ferry dock, it’s just 24km over the Lyngen to the Lyngseidet–Olderdalen car ferry, by means of which you can rejoin the E6 at Olderdalen, some 220km south of Alta. This route is at its most spectacular between Svendsby and Lyngseidet, with the road nudging along a narrow channel flanked by the imposing peaks of the Lyngsalpene, or Lyngen Alps. Beyond Olderdalen, the E6 eventually enters the province of Finnmark as it approaches the hamlet of Langfjordboten, at the head of the long and slender Langfjord. Thereafter, the road sticks tight against the coast en route to Kåfjord.

GETTING AROUND: THE ROAD TO FINNMARK

Car ferries Breivikeidet–Svensby car ferry (hourly; Mon–Fri 6.30am–10.30pm,

Sat 8.10am–8.10pm, Sun 8.10am–9.55pm; 25min; 87kr car and driver;

![]() 77 71 14 00,

77 71 14 00, ![]() bjorklid.no); Lyngseidet–Olderdalen car ferry (hourly;

Mon–Fri 7.20am–9.05pm, Sat 9.05am–7.20pm, Sun 9.05am–9.05pm; 40min;

122kr car and driver;

bjorklid.no); Lyngseidet–Olderdalen car ferry (hourly;

Mon–Fri 7.20am–9.05pm, Sat 9.05am–7.20pm, Sun 9.05am–9.05pm; 40min;

122kr car and driver; ![]() 77 71 14 00,

77 71 14 00, ![]() bjorklid.no).

bjorklid.no).

Kåfjord

Some 60km from Langfordboten is the tiny village of KÅFJORD, whose sympathetically restored nineteenth-century church was built by the English company who operated the area’s copper mines until they were abandoned as uneconomic in the 1870s. The Kåfjord itself is a narrow and sheltered arm of the Altafjord, which was used as an Arctic hideaway by the Tirpitz and other German battleships during World War II.

Alta

Some 20km from Kåfjord, ALTA’s primary claim to fame is the most extensive area of prehistoric rock carvings in northern Europe, which are impressive enough to have been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. At first blush, however, the view of the town is somewhat less than encouraging. With a population of around 20,000, it comprises a string of unenticing modern settlements that spread along the E6 for several kilometres. The ugliest part is Alta Sentrum, now befuddled by a platoon of soulless concrete blocks. World War II polished off much of the local Sámi culture that used to thrive here, as well as destroying all the old wooden buildings that once clustered together in Alta’s oldest district, Bossekop, where Dutch whalers settled in the seventeenth century.

That being said, the settlement is an excellent place to base oneself in

for explorations out to the Finnmark plateau. The area around here gets very

green in the summer months, and hiking, canyoning and riverboat safaris are

all on offer. In the wintertime, the stable (if very cold) climate allows

for plenty of outdoor activities, including

dog-sledding, snowmobiling, cross-country skiing and chasing the northern

lights. Additionally, Europe’s largest dog-sled race, the Finnmarksløpet (![]() finnmarkslopet.no), is put

on here in mid-March, complemented by a big week-long cultural celebration,

the Borealis Winter Festival.

finnmarkslopet.no), is put

on here in mid-March, complemented by a big week-long cultural celebration,

the Borealis Winter Festival.

Alta’s prehistoric rock carvings and the Alta Museum

Altaveien 19 • May to mid-June daily 8am–5pm; mid-June to

Aug daily 8am–8pm; Sept–April Mon–Fri 8am–3pm, Sat & Sun

11am–4pm • 90kr • ![]() alta.museum.no • A limited local bus service – bybussen – runs from the bus station south to

Bossekop and the museum (Mon–Sat every 30min–1hr; 10min);

alternatively call Alta Taxi (

alta.museum.no • A limited local bus service – bybussen – runs from the bus station south to

Bossekop and the museum (Mon–Sat every 30min–1hr; 10min);

alternatively call Alta Taxi (![]() 78 43 53 11)

78 43 53 11)

Accessed along the E6, Alta’s prehistoric rock carvings, the Helleristningene i Hjemmeluft, form part of the Alta Museum. Count on at least an hour to view the carvings and appreciate the site. A visit begins in the museum building, 5km from town, where there’s a wealth of background information on the carvings in particular and on prehistoric Finnmark in general. It also offers a potted history of the Alta area, with exhibitions on the salmon-fishing industry, copper mining and so forth.

The rock carvings themselves extend down the hill from the museum to the fjordside along a clear and easy-to-follow footpath and boardwalk that stretches for just under 3km. On the trail, there are a dozen or so vantage points offering close-up views of the carvings, recognizable through highly stylized representations of boats, animals and people picked out in red pigment (the colours have been retouched by researchers). They make up an extraordinarily complex tableau, whose minor variations – there are four identifiable bands – in subject matter and design indicate successive historical periods. The carvings were executed between 2500 and 6000 years ago, and are indisputably impressive: clear, stylish, and touching in their simplicity. They provide an insight into a prehistoric culture that was essentially settled and largely reliant on the hunting of land animals, who were killed with flint and bone implements; sealing and fishing were of lesser importance. Many experts think it likely the carvings had spiritual significance because of the effort that was expended by the people who created them, but this is the stuff of conjecture.

Around Alta: Sorrisniva

![]() 78 43 33 78,

78 43 33 78, ![]() sorrisniva.no • Call for details about shuttle transfers

from Alta

sorrisniva.no • Call for details about shuttle transfers

from Alta

Aside from the rock carvings, the only real reason to linger hereabouts is the Alta Friluftspark, 20km to the south of town off Highway 93, beside the river in Storelvdalen. Here, all manner of Finnmark experiences are on offer, from snowmobile tours, dog-sled trips, ice-fishing and reindeer racing in winter, to summer boat trips along the 400m-deep Sautso canyon, Scandinavia’s largest.

ARRIVAL AND DEPARTURE: ALTA

By bus Alta is something of a transport hub. Long-distance buses pull into the bus station just off the E6 at Alta Sentrum. To reach Nordkapp, passengers must change – and overnight – in Honningsvåg. The following bus companies run onward services:

Boreal (![]() boreal.no) to:

Hammerfest (1–4 daily; 2hr 30min); Honningsvåg (1–2 daily;

4hr); Karasjok (1–2 daily except Sat; 5hr); Kautokeino (1–3

daily except Sat; 2hr 15min); Kirkenes (3 weekly;

11–13hr).

boreal.no) to:

Hammerfest (1–4 daily; 2hr 30min); Honningsvåg (1–2 daily;

4hr); Karasjok (1–2 daily except Sat; 5hr); Kautokeino (1–3

daily except Sat; 2hr 15min); Kirkenes (3 weekly;

11–13hr).

Torghatten Nord (![]() tts.no) to:

Honningsvåg (1–2 daily; 4hr); Narvik (1 daily; 9hr 25min);

Tromsø (1 daily; 7hr).

tts.no) to:

Honningsvåg (1–2 daily; 4hr); Narvik (1 daily; 9hr 25min);

Tromsø (1 daily; 7hr).

INFORMATION

Tourist office Bjorn Wirkolas vei 11, in the same building as the bus

terminal (June & Aug daily 9am–6pm; July daily 9am–8pm;

Sept–May Mon–Fri 9am–3.30pm, Sat 10am–3pm; ![]() 78 44 50

50,

78 44 50

50, ![]() visitalta.no); near the Coop supermarket, Bossekop

shopping centre (mid-June to mid-Aug only Mon–Fri 10am–6pm; same

number). Both branches of the tourist office issue free town

maps, will advise on hiking

the Finnmarksvidda and help with finding accommodation.

The latter is a particularly useful service if you’re dependent

on public transport – the town’s hotels and motels are widely

dispersed – or if you’re here at the height of the

season.

visitalta.no); near the Coop supermarket, Bossekop

shopping centre (mid-June to mid-Aug only Mon–Fri 10am–6pm; same

number). Both branches of the tourist office issue free town

maps, will advise on hiking

the Finnmarksvidda and help with finding accommodation.

The latter is a particularly useful service if you’re dependent

on public transport – the town’s hotels and motels are widely

dispersed – or if you’re here at the height of the

season.

ACCOMMODATION

HOTELS AND GUESTHOUSES

Bårstua Gjestehus Kongleveien 2a ![]() 78 43 33 33,

78 43 33 33, ![]() baarstua.no.

Of Alta’s several guesthouses, this is the most appealing,

located just off the E6 on the north side of town. The eight

rooms here are large and pleasant enough and all of them

have kitchenettes. 830kr

baarstua.no.

Of Alta’s several guesthouses, this is the most appealing,

located just off the E6 on the north side of town. The eight

rooms here are large and pleasant enough and all of them

have kitchenettes. 830kr

Igloo Hotell Sorrisniva ![]() 78 43 33 78,

78 43 33 78, ![]() sorrisniva.no.

Sorrisniva boasts a 100-bed, 1100-square-metre hotel built

entirely out of ice and snow, including the beds and the

glasses in the bar. It’s set near the riverside, and while

staying in an ice hotel seems gimmicky, it’s a (erm) cool –

and memorable – way of avoiding the bland Ikea decor and

amenities of the chain hotels. As the hotel is fantastically

popular, advance reservations are essential. Late Jan to

early April only. 3990kr

sorrisniva.no.

Sorrisniva boasts a 100-bed, 1100-square-metre hotel built

entirely out of ice and snow, including the beds and the

glasses in the bar. It’s set near the riverside, and while

staying in an ice hotel seems gimmicky, it’s a (erm) cool –

and memorable – way of avoiding the bland Ikea decor and

amenities of the chain hotels. As the hotel is fantastically

popular, advance reservations are essential. Late Jan to

early April only. 3990kr

Nordlys Hotell Alta Bekkefaret 3 ![]() 78 45 72 00,

78 45 72 00, ![]() nordlyshotell.no.

Located just opposite the Bossekop tourist office, this Best

Western hotel sports a rather uninviting mishmash of styles,

but offers large, comfortable if somewhat spartan rooms.

1095kr

nordlyshotell.no.

Located just opposite the Bossekop tourist office, this Best

Western hotel sports a rather uninviting mishmash of styles,

but offers large, comfortable if somewhat spartan rooms.

1095kr

Thon Hotel Vica Fogdebakken 6 ![]() 78 48 22 22,

78 48 22 22, ![]() thonhotels.com.

Among Alta’s several hotels, this is one of the more

appealing. Occupying a wooden building that started out as a

farmhouse a couple of minutes’ walk from the Bossekop

tourist office, it’s a small, cosy place with two dozen

smart, modern rooms. Also has a suntrap of a terrace and

free wi-fi. 1045kr

thonhotels.com.

Among Alta’s several hotels, this is one of the more

appealing. Occupying a wooden building that started out as a

farmhouse a couple of minutes’ walk from the Bossekop

tourist office, it’s a small, cosy place with two dozen

smart, modern rooms. Also has a suntrap of a terrace and

free wi-fi. 1045kr

CAMPSITE

Alta River Camping ![]() 78 43 43 53,

78 43 43 53, ![]() alta-river-camping.no.

The best of the campsites around Alta, this well-equipped,

four-star site is set on a large green plot right on the

Alta River. They have tent spaces here as well as

hotel-style rooms and cabins, some of which have en-suite

baths (others share), plus a sauna right on the water.

Located about 5km out of town along Highway 93, which

branches off the E6 in between Bossekop and the rock

paintings. Open year-round. Tents 170kr, doubles

400kr, cabins 600kr

alta-river-camping.no.

The best of the campsites around Alta, this well-equipped,

four-star site is set on a large green plot right on the

Alta River. They have tent spaces here as well as

hotel-style rooms and cabins, some of which have en-suite

baths (others share), plus a sauna right on the water.

Located about 5km out of town along Highway 93, which

branches off the E6 in between Bossekop and the rock

paintings. Open year-round. Tents 170kr, doubles

400kr, cabins 600kr

EATING AND DRINKING

Alfa-Omega Markedsgata 16 ![]() 78 44 54 00,

78 44 54 00, ![]() alfaomega-alta.no. Omega is the continental eatery;

Alfa is the no-holds-barred bar,

whose vaguely Cuban aesthetic manages to attract more than its

share of fortysomethings.

Mon–Wed 8pm–midnight, Thurs 7pm–1am, Fri 6pm–2.30am, Sat noon–2.30am.

alfaomega-alta.no. Omega is the continental eatery;

Alfa is the no-holds-barred bar,

whose vaguely Cuban aesthetic manages to attract more than its

share of fortysomethings.

Mon–Wed 8pm–midnight, Thurs 7pm–1am, Fri 6pm–2.30am, Sat noon–2.30am.

Rica Hotel Alta Løkkeveien 61 ![]() 78 48 27 00.

Large, smart hotel restaurant that’s part of the Arctic Menu scheme, specializing in regional

delicacies – cloudberries, reindeer and the like. Mains cost

around 200kr.

Open daily noon–11.30pm.

78 48 27 00.

Large, smart hotel restaurant that’s part of the Arctic Menu scheme, specializing in regional

delicacies – cloudberries, reindeer and the like. Mains cost

around 200kr.

Open daily noon–11.30pm.

The Finnmarksvidda

Venture far inland from Alta and you enter the Finnmarksvidda, a vast mountain plateau which spreads southeast up to and beyond the Finnish border. Rivers, lakes and marshes lattice the region, but there’s nary a tree, let alone a mountain, to break the contours of a landscape whose wide skies and deep horizons are nevertheless eerily beautiful. Distances are hard to gauge – a dot of a storm can soon be upon you, breaking with alarming ferocity – and the air is crystal-clear, giving a whitish lustre to the sunshine. A handful of roads cross this expanse, but for the most part it remains the preserve of the few thousand semi-nomadic Sámi who make up the majority of the local population. Many still wear traditional dress, a brightly coloured, wool and felt affair of red bonnets and blue jerkins or dresses, all trimmed with red, white and yellow embroidery. You’ll see permutations on this traditional costume all over Finnmark, but especially at roadside souvenir stalls and, on Sundays, outside Sámi churches.

Despite the slow encroachments of the tourist industry, lifestyles on the Finnmarksvidda have remained remarkably constant for centuries. The main occupation is reindeer herding, supplemented by hunting and fishing, and the pattern of Sámi life is still mostly dictated by the biology of these animals. During the winter, the reindeer graze the flat plains and shallow valleys of the interior, migrating towards the coast in early May as the snow begins to melt, and temperatures inland begin to climb, even reaching 30°C on occasion. By October, both people and reindeer are journeying back from their temporary summer quarters on the coast. The long, dark winter is spent in preparation for the great Easter festivals, when weddings and baptisms are celebrated in the region’s two principal settlements, Karasjok and – more especially – Kautokeino. Summer visits, on the other hand, can be rather disappointing, culturally speaking at least, since many families and their reindeer are kicking back at coastal pastures and there is precious little activity in either town. Still, your best bet for spotting small herds are along the road to Hammerfest and in the area around Nordkapp.

The best time to hike the Finnmarksvidda is in late August and early September, after the peak mosquito season and before the weather turns cold. For the most part the plateau vegetation is scrub and open birch forest, which makes the going fairly easy, though the many marshes, rivers and lakes often impede progress. There are a handful of clearly demarcated hiking trails as well as a smattering of appropriately sited but unstaffed huts; for detailed information, ask at Alta tourist office.

EASTER FESTIVALS IN THE FINNSMARKSVIDDA

As neither of the Finnsmarksvidda region’s two principal settlements, Karasjok and Kautokeino, is particularly appealing in itself, Easter is without question the best time to be here, when the inhabitants celebrate the end of the polar night and the arrival of spring. There are folk-music concerts, church services and traditional sports, including the famed reindeer races – not, thank goodness, reindeers racing each other (they would never cooperate), but reindeer pulling passenger-laden sleds. Details of the Easter festivals are available at any Finnmark tourist office.

ARRIVAL AND DEPARTURE: THE FINNMARKSVIDDA

By bus Operated by Boreal (![]() 177,

177, ![]() boreal.no), bus services

across the Finnmarksvidda are patchy: except on Sat, there are 1–2

buses a day from Alta to Kautokeino (just over 2hr) and to Karasjok

(5hr), but nothing between Kautokeino and Karasjok. Some

Alta–Karasjok buses continue to Kirkenes (12hr), while a further

service links Karasjok with Hammerfest (Mon–Fri 3–4 daily, Sat &

Sun 1–2 daily; 3hr).

boreal.no), bus services

across the Finnmarksvidda are patchy: except on Sat, there are 1–2

buses a day from Alta to Kautokeino (just over 2hr) and to Karasjok

(5hr), but nothing between Kautokeino and Karasjok. Some

Alta–Karasjok buses continue to Kirkenes (12hr), while a further

service links Karasjok with Hammerfest (Mon–Fri 3–4 daily, Sat &

Sun 1–2 daily; 3hr).

By car From Alta, the only direct route into the Finnmarksvidda is south along Highway 93 to Kautokeino, a distance of 130km. Just short of Kautokeino, about 100km from Alta, Highway 93 connects with Highway 92, which travels the 100km or so northeast to Karasjok, where you can rejoin the E6 (but well beyond the turning to Nordkapp).

Kautokeino

It’s a two-hour drive or bus ride from Alta across the Finnmarksvidda to KAUTOKEINO (Guovdageaidnu in Sámi), the principal winter camp of the Norwegian Sámi and their reindeer, who are kept in the surrounding plains. The Sámi are not, however, easy town dwellers and although Kautokeino is very useful to them as a supply base, it’s still a desultory, desolate-looking place straggling along Highway 93 for a couple of kilometres, with the handful of buildings that pass for the town centre gathered at the point where the road crosses the Kautokeinoelva River.

THE SÁMI

The northernmost reaches of Norway, Sweden and Finland, plus the Kola peninsula of northwest Russia, are collectively known as Lapland. Traditionally, the indigenous population were called “Lapps”, but in recent years this name has fallen out of favour and been replaced by the term Sámi, although the change is by no means universal. This more commonly used term comes from the Sámi word sámpi referring to both the land and its people, who now number around 70,000 scattered across the whole of the region. Among the oldest peoples in Europe, the Sámi most likely descended from prehistoric clans who migrated here from Siberia by way of the Baltic. Their language is closely related to Finnish and Estonian, though it’s somewhat misleading to speak of a “Sámi language” as there are, in fact, three distinct versions, each of which breaks down into a number of markedly different regional dialects. All share many common features, however, including a superabundance of words and phrases to express variations in snow and ice conditions.

Originally, the Sámi were a semi-nomadic people, living in small communities (siidas), each of which had a degree of control over the surrounding hunting grounds. They lived off hunting, fishing and trapping, preying on all the edible creatures of the north, but it was the wild reindeer that supplied most of their needs. This changed in the sixteenth century when the Sámi moved over to reindeer herding, with communities following the seasonal movements of the animals.

The contact the Sámi have had with other Scandinavians has almost always been to their disadvantage. In the ninth century, they paid significant fur, feather and hide taxes to Norse chieftains. Later, in the seventeenth century, they faced colonization and moves to dislocate their culture from the various thrones in Sweden, Russia and Norway. The frontiers of Sámiland were only agreed in 1826, by which point hundreds of farmers had settled in “Lapland”, to the consternation of its native population. By that point, Norway’s Sámi had kowtowed to Protestant missionaries and accepted the religion of their colonizers – though the more progressive among them did support the use of Sámi languages and even translated hundreds of books into their language. In the nineteenth century, the government’s aggressive Social Darwinist policy of “Norwegianization” banned the use of indigenous languages in schools, and only allowed Sámi to buy land if they could speak Norwegian. Only in the 1950s were these policies abandoned and slowly replaced by a more considerate, progressive approach.

1986 was a catastrophic year for the Sámi: the Chernobyl nuclear disaster contaminated much of the region’s flora and fauna, which effectively meant the collapse of the reindeer export market. While reindeer herding is now the main occupation of just one-fifth of the Sámi population, expressions of Sámi culture have expanded. Traditional arts and crafts are now widely available in all of Scandinavia’s major cities and a number of Sámi films – including the critically acclaimed Veiviseren (The Pathfinder) – have been released. Sámi music (joik) has also been given a hearing by world-music, jazz and even electronica buffs. Although their provenance is uncertain, the rhythmic song-poems that constitute joik were probably devised to soothe anxious reindeer; the words are subordinated to the unaccompanied singing and at times are replaced altogether by meaningless, sung syllables.