11 IBM ON THE GLOBAL STAGE

When we and other progressive firms do something new, its effect spreads and changes the character of an area of the economy. Little by little, our example spreads over a wide area.

—FRENCH IBM MANAGER, 19601

WHEN WORLD WAR II ended, IBM picked up the pieces of its worldwide operations. In a staff meeting, Thomas J. Watson Sr. declared the company’s performance outside the United States “nothing short of a disgrace.”2 Tom Watson Jr. thought demand was strong; it was just that IBM could not deliver products because of shortages in supply. IBM took the quick step of sending equipment no longer needed by the U.S. military in Europe to its local factories for refurbishing. The stratagem worked and also provided employment for European IBM veterans returning to the company. Watson Jr. recalled that “with a few hours’ work and a new coat of paint, those machines were something they could sell.”3 But the “Old Man” wanted more, so he poured resources into Europe, reestablishing offices and contacts with customers.

Watson Sr. settled on two strategies for jump-starting business in Europe. Picking up the story of World Trade from chapter 7, first he created his own internal common market a decade before the Europeans did. He ordered his tiny European factories to make parts for both their own country’s market and for export to IBM factories and suppliers in other nations. For example, 60 percent of the parts made in Germany would be for the German market, leaving 40 percent of the output available for sale by IBM in other European countries. An IBM country company earned foreign exchange credits, which it used to import parts, making it possible for IBM to avoid high national tariffs for finished products. It rarely had to ship a completed machine that had no local parts. Watson Jr. explained, “This trading around allowed us to operate on a much larger scale, and far more efficiently” than any company constrained within one country.4 It is a crucial idea in understanding IBM’s global strategies, because for the next half century IBM developed increasingly integrated global product plans, production, and marketing strategies.5 This approach helps to explain how IBM could move quickly against slower-moving European “national champions” in the 1960s to 1980s. Second, Watson Sr. hired local nationals to run and staff national companies to optimize local cultural and legal traditions and to leverage the local language and “know-how.” On the whole, he chose effective country leaders. They and their staffs grew the company at remarkable rates in the years that followed.6

Recall what some historians noted was an act of nepotism, that Watson Sr. divided IBM into two halves: the U.S. market for Tom Jr. to run, and everything else, to be run by Tom Jr.’s younger brother, Arthur. In October 1948, Watson Sr. told Tom Jr. of his plan, adding that Domestic would retain worldwide responsibility for finance, research, and product development. Tom Jr. disliked the idea, but several days later, his father told the brothers what he wanted to do. Tom Jr. admitted later to being jealous that his less experienced younger brother was about to be made his equal. Tom Jr. relayed to his father reasons for not forming World Trade (WT) Corporation: redundant staffs and overhead, that WT would likely reduce IBM’s manufacturing productivity, and so on. Watson Sr. stood up and barked at Tom Jr., “What are you trying to do, prevent your brother from having an opportunity?” That is how IBM World Trade came into being.

The rest of this chapter would be anticlimactic if we just reported the new structure of 1949 with WT becoming a wholly owned subsidiary that owned country companies, and likewise if we just reported that Tom Jr. considered the move a success: “It capitalized on Europe’s economic recovery, financed itself through its own profits and foreign borrowings, and grew as fast as the American company.”7 But it was a momentous event. The story is more interesting because of how IBM ran WT. When one fills an organization “with some of the most talented businessmen in Europe,” things become complicated.8 The same happened in Latin America and Asia. By 1953, these “most talented businessmen” employed 15,000 people, about half the size of Domestic. Arthur Watson could take credit for this rapid growth, too, blending the best of Domestic with local national opportunities, and with both sides of the business collaborating enough to leverage each other’s assets and capabilities. Watson Sr. was pleased. Under Tom Jr.’s command, the decentralization of authority and responsibility articulated in Williamsburg, Virginia, extended into WT. In various iterations over the next half century, World Trade divided itself into additional geographic companies. Within them, they established regional offices and branch offices, with laboratories and factories reporting to global manufacturing or research divisions.

This chapter focuses on a broadly diverse group of issues. It is a history of IBM’s non-U.S. operations. Historians and others writing about WT comment as if it were almost a separate company from IBM Domestic.9 While this view is convenient when writing a chapter or an article, it is misleading, because Corporate operated a globally integrated firm, a point insufficiently recognized by students of the company’s history.10 Senior executives viewed WT as an extension of the network of factories, laboratories, and sales regions that existed in Domestic. For this reason, the story told here includes what otherwise would be left out of the story of IBM’s foreign operations, notably the work of CEO Frank Cary, who I rescue from obscurity and argue was one of the most powerful and best CEOs in IBM’s history. IBM evolved into a global behemoth more complex in structure than the company Watson Sr. ran before World War II. IBM’s non-Domestic business grew to where half of the company’s revenue came from outside the United States.

Historians have recently paid increased attention to emerging economies, looking at what happened in areas such as Asia and Latin America. Crucial to such investigations is how multinational corporations interacted with businesses and governments in these economies. This chapter is a detailed case study of how one firm did that. As Geoffrey Jones, Gareth Austin, and Carlos Dávila argued, foreign influence on local economies was extensive; it could even be called “foreign domination.” As this chapter demonstrates, that domination included adoption of U.S. managerial practices, such as those proffered by IBM.11

We begin by describing the core of IBM’s immediate postwar foreign operations—Europe and the formation of WT—followed by brief histories of IBM’s operations in Asia and Latin America. Those discussions represent the first story.12 We then turn to the rising tide of global competition and the role played by Cary in creating the IBM international behemoth, describe IBM’s departure from India as part of the global evolution of the firm rather than as a result of IBM’s Asia’s experience, and analyze how globalizing changed IBM. We summarize the discussion by analyzing IBM’s global financial results.

EUROPE: WORLD TRADE’S GLOBAL EPICENTER

Between the 1940s and the end of the 1980s, IBM’s non-U.S. operations were centered in Western Europe and Japan. IBM’s European core consisted of the United Kingdom (largely England), France, West Germany, and to a lesser extent Italy, Sweden, Austria, Switzerland, and Spain. IBM dominated computer sales in Europe to a greater extent than in the United States, with sales surging in the early 1960s, compelling European rivals to restructure and to ask their home governments for support and protection.13 In the late 1960s and 1970s, IBM retained its dominance, with its market share rising to more than 80 percent, in contrast to the more competitive U.S. market, where its share vacillated between 40 and 60 percent.14 The third phase of the Personal Computer as well as mainframes in the 1980s saw the rise of German, Japanese, and U.S. rivals.

IBM World Trade, presaged in earlier chapters, was about creating a business similar to the U.S. company. While Arthur Watson balanced conformity to company-wide practices with those of national companies, he took advantage of global product strategies and developed local capacity to invent and manufacture. WT was held accountable for generating profitable revenue and, just as important, for maintaining or expanding market share.15 Local IBMers knew where every system was installed, including their rivals’, and how many were on order from IBM and other vendors. IBM’s definition of market share remained nuanced, as it included share by product, size of enterprise, and industry. IBM’s accountants sliced revenue and profit data in every conceivable way and then used this data to recommend financial actions to leverage profits and market share.

Figure 11.1

Arthur K. Watson, the first leader of World Trade Corporation. Photo courtesy of IBM Corporate Archives.

The U.S. government’s antitrust case influenced IBM’s actions around the world. The logic of its suit influenced European regulators and companies competing against IBM. The criticism against IBM is straightforward and is discussed in detail in chapter 12. If a company had a high market share, it could make products in sufficient quantity to drive down production costs below those of rivals while maintaining higher prices, generating expanding profits from each sale and from more sales. Government economists argued that IBM did this to such an extent that its competitors could not compete against Big Blue. U.S. government lawyers argued that violated antitrust laws.16

WT reflected a parallel IBM universe that operated alongside Domestic, almost out of sight for most U.S. IBMers. In Europe, Domestic seemed always present, even though the majority of employees were local nationals. In the early 1950s, Watson Sr. spent up to four months at a time traveling through Europe to jump-start business and, of course, his son—an American—ran WT; his successor, Gil Jones, was also American. By the mid-1960s, when over 10,000 Europeans worked at IBM, fewer than 200 Americans worked in Europe. Nonetheless, European citizens, their governments, and local employees thought of IBM as an American company.

Ties bound both sides of the Atlantic, less so Japan, and nowhere more than in creating and manufacturing products. Product developers in U.S. and European laboratories and factories discussed products in face-to-face meetings. Beginning in the late 1950s, European laboratories assumed responsibility for worldwide development of IBM’s offerings, such as Hursley, England, for CICS software. Since the 1960s, CICS had made it possible for mainframes to send data to each other over networks. Thousands of European customers visited factories and laboratories in the United States with their IBM salesmen. They attended seminars in Poughkeepsie and Endicott until the 1990s and subsequently at briefing centers in Palisades, Hawthorne, and Somers.17

IBM’s customers were similar around the world. The largest organizations were overwhelmingly customers. IBM cultivated midsized organizations with the 650, 1401, and smaller S/360s. While not as profitable, since smaller systems were priced less expensively and required additional “hand-holding” to introduce first-time users to computing, they represented the future of IBM. Some became large enterprises, while the majority increased their computing. It was essential, however, to get all accounts to use IBM’s technologies, because their dependence dampened growth in the future cost of selling to them and constrained competition. With remarkable speed, IBM dominated the Western European market. How did that happen? The answer turns on the mundane routine of well-executed business practices that valued speed of execution, effectiveness, good salesmanship, and creative and knowledgeable pricing, contractual terms and conditions, marketing, and advertising. A review of the experiences of several countries illustrates how.

Early on, in the United Kingdom, most notably in England, IBM had been selling time-recording equipment and leasing Hollerith hardware through local agencies. In the 1940s, Britain led the world in developing early computer technology and became the earliest extensive user of computing in Europe.18 Two British electronics manufacturers sold computers: English Electric and Ferranti. A third company, J. Lyons, a food manufacturer that also ran a chain of teashops, did also.19 Its machine, called LEO (Lyons Electronic Office), became available in 1951. British Tabulating Machine (BTM) and Powers-Samas sold punch card equipment—the first, Hollerith products, and the second, Powers’s own—in the same markets chased by IBM and Remington Rand. Both U.S. firms terminated contracts with these British firms and set up their own operations, beginning to sell locally in 1951. The British firms that had these earlier American alliances remained in their traditional data processing markets in the 1950s, while IBM and the others moved into computers. Prodded by British officials, BTM slowly dabbled with computing, while IBM pushed aggressively ahead. In 1959, BTM and Powers-Samas combined to form International Computers and Tabulators (ICT).

IBM’s 1401 killed off the punch card tabulator business, allowing it to grab the lead from British vendors for computers. British computing in the 1960s was about accommodation of this new reality, with the result that IBM permanently destroyed any possibility of local vendors in Britain or elsewhere seriously challenging it. The 1401 bought IBM 40 percent of all computers installed in Great Britain. Until the end of the 1960s, ICL retained 49 percent of the local market.20 IBM’s hold on the high end with S/360s continued, and likewise in the 1970s with S/370s and 4300s. The number of users increased, too.

France offered a potentially larger market. IBM’s presence there became subject to greater national and public discussion than in Britain. The French saw IBM as a threat to its economic and cultural independence sooner than Britain had. SEA (Société d’Electronique et d’Automatisme), a French computer start-up, introduced its first computer in 1955. CBM (Compagnie des Machines Bull), like the British BTM, entered the computer business in the second half of the 1950s. CSF (Compagnie Générale de Télegraphie sans Fil) and CGE (Compagnie Générale de Electricité), two large enterprises, sold computers in the early 1960s. Alarm bells went off in Paris because before anybody could stop IBM, it was growing rapidly.21 In 1949, IBM had 166,000 square feet of French manufacturing and laboratory space, not including sales offices or repair centers. It employed 2,186 people in France. In 1960, just before introducing the 1401, IBM’s manufacturing and laboratory space had grown to 553,000 square feet and it employed 6,200 IBMers in France, making it one of the larger companies in France.22 Its employees worked in one factory, two card-manufacturing facilities, two development laboratories, and 32 sales and service bureau centers scattered around the country, even in French Africa, Madagascar, and Vietnam. The French plant outside the little town of Corbell-Essonnes, 20 miles upstream from Paris on the Seine River, had just been built. It exported parts and equipment to 64 countries and became one of France’s largest industrial facilities. IBM’s firepower proved even greater, however, because of its 6,200 employees, of whom only 23 percent worked in manufacturing, the rest being engaged in R&D or sales. So even before the magic of the 1401 (later the S/360), IBM had a formidable presence in France.23 A similar story could be told of IBM’s even larger presence in West Germany and its expanding operations in Italy, Spain, Sweden, Finland, Ireland, and the Netherlands, among other nations, all made possible by reinvesting locally generated profits back into the country organizations, augmented by additional funds from company-wide R&D and manufacturing.24

But the great battle for the European market was fought in France. Step back a half dozen years before IBM introduced the 1401 and see how its rapidly expanding infrastructure made it possible for it to enter the French market in 1956 with the 650, where it found an active, competitive computer market. It proved to be what observers called an “epic struggle IBM is waging to hold its own in the crucial electronic data processing field.”25 When the 1401 came to France in 1961, it caught all vendors flatfooted. As in Britain, the French government encouraged local firms to step up their game, expand further into computing, and form alliances and mergers, but it was too late. IBM gained control of 50 percent of the market.26 In the 1960s, other U.S. firms entered the market, notably GE and Control Data, while CMB licensed RCA equipment to sell.

The French government anointed a “national champion,” Compagnie Internacionale pour l’Informatique (CII), in the second half of the 1960s. While officials encouraged local customers to consider buying French first, even government agencies bought from IBM, notably its largest departments and the military. The government initiated the first of several Plans Calculs, a national strategy for developing a local computer industry. It portrayed IBM as an American firm, even though it was one of the largest corporate employers in the country and always ranked in the top half dozen French exporters of machines and parts. Officials and the media fixated on threats to the nation’s business and culture from American businesses, lumping IBM into that milieu. Meanwhile, GE took control of Machines Bull, a major local company, in 1964.

In 1966, the U.S. National Security Administration (NSA) determined that a CDC system should not be sold to the French military, so the U.S. Department of Defense, which handled the formal export permission process, prevented Control Data from doing so. NSA was concerned that technological information relevant to national security could leak out. That so infuriated President Charles de Gaulle that he launched his Calcul plans in 1967. These efforts failed to stop IBM. IBM’s aggressive pricing, quick introduction of new products, and effective “account management” ensured that it dominated the French mainframe market. In the 1970s, French studies discussed the role of IBM and other multinationals in society. The public learned that IBM owned over 70 percent of the market and that no French company held even 10 percent. The government invested over one billion dollars in its local industry between 1967 and 1982, but to little avail.27

IBM steamrolled across Western Europe. The larger the enterprise, the quicker IBM penetrated it. Countries with smaller firms were slower in using computers. Not until PCs came into wide use in the 1980s and 1990s did the market for computing dramatically expand across Europe. By the early 1980s, WT had assumed the organizational structure it retained until the end of the century. WT consisted of two parts. First, there was EMEA (Europe, Middle East, and Africa), with Europe the largest portion. The second part, AFE (Americas, Far East), consisted largely of Japan and everyone else. As of the mid-1980s, EMEA was twice the size of AFE. Both were subject to Armonk’s dictates on products, revenue targets, and pricing. Hundreds of employees at WT headquarters, in the country organizations, and at IBM’s two offshore WT quasiheadquarters in Paris and Tokyo tracked expenses and prospects, and coordinated assignments for the development and manufacture of goods. Europe dominated EMEA, and Japan dominated AFE.

EXPANSION INTO ASIA

Japan came out of World War II devastated. Following the war, it was occupied by Allied military forces for a half decade. Its economy lay in a shambles. Use of data processing remained largely the purview of the occupation forces. Telecommunications and electronics companies came back in the early 1950s, including Nippon Electric (NEC), Fujitsu, Hitachi, and Oki. Unlike their European counterparts, these remained in the computer industry, challenging IBM. How did Japan’s computer industry differ from Western Europe’s? The industries in both regions initially did well because of national reconstruction, a process that unfolded more quickly in Japan than in many parts of Europe. By 1954, Japanese transistorized computers appeared. The government arranged for investments in its local industry beginning in 1957. Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), its powerful economic development agency, invested in the economy and in individual companies, and coerced collaboration and increased competition within industries, exercising more authority than its European counterparts. MITI’s staff did not hesitate to use their power.

IBM’s records are filled with complaints about MITI’s heavy-handed treatment of foreign companies, including IBM. MITI slapped tariffs on foreign computers of between 15 and 25 percent. To participate in the local market, IBM agreed to license patents of interest to Japanese companies. IBM was not allowed to bring in capital or technology to manufacture in Japan. In 1960, MITI licensed IBM computer patents for a 5 percent royalty fee.28 MITI negotiated similar licensing agreements with other firms, such as TRW and Sperry Rand. It used subsidies, low-interest loans, grants, and other financial tools to nurture the local computer industry. It forced Japanese companies to compete against each other. MITI did not choose “national champions.” Japanese authorities made it difficult for IBM to sell. Customers needed permission to bring in a “foreign” computer, and they first had to consider local suppliers. By the early 1960s, all foreign vendors combined owned about 60 percent of the Japanese market, but that had slipped to less than half by the late 1980s. Local companies learned how to compete at home and abroad. They were able to compete against IBM’s 1401. After IBM introduced its S/360, Japanese vendors responded quickly with compatible systems. Hitachi, NEC, and Toshiba entered the market against IBM. By 1968, Fujitsu was the leading computer vendor in Japan.

MITI’s initiative to develop advanced computer technologies, called the “Very High Speed Computer System Project,” generated consternation among IBM’s scientists, vendors on both sides of the Atlantic, and even in the U.S. Department of Defense. In the mid-1980s, European and U.S. manufacturers worried about Japan’s ability to penetrate their markets with inexpensive high-quality television sets, stereo equipment, automobiles, personal computers, other electronic devices, and even wristwatches, creating the same angst in corporate America as the French and British experienced in the 1960s and 1970s regarding U.S. vendors.29

A feature of IBM’s relations with Japan was the constant and complicated negotiations for permission to operate in the country. All agreements existed only for a few years, yet IBM was able to retain 100 percent ownership of IBM Japan and to manufacture in the country.30 Despite constraints, IBM remained profitable over many years. IBM Japan employed local nationals from top to bottom. IBM concluded that its Japanese customers would support it against government insistence on partial local ownership and thus never had to surrender it.31 After the government backed down on the issue in the 1970s, IBM increased its investment in local manufacturing and education.

IBM managers believed that many of the business practices in Japanese companies had been borrowed from them, largely in the 1950s. As one IBM manager mused, “IBM was probably also a key model … for the Japanese corporations,” thinking of IBM’s and Japan’s similar full-employment policies, job enrichment programs, continuing training, quality control, intense customer service, and ethics.32 That did not make doing business in Japan any easier. American IBM executives resented Japanese policies and the brevity of its own Japanese employees when reporting results to IBM Corporate. Given the competitive environment and MITI’s hostility, the company still held 30 percent or more of the mainframe market in the 1970s and 1980s.33

As other Asian economies industrialized in the 1960s and later, IBM expanded into them. These included Indonesia, Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea.34 Australia and New Zealand were already active markets in the 1950s, similar to those in the United Kingdom and Canada. IBM’s relative success in Japan, however, allowed it to expand across Asia in the 1950s to 1980s, opening sales offices that for a time reported to IBM Japan until they had critical mass to establish themselves as country companies.

ELUSIVE LATIN AMERICA

It seems that every large North American corporation plans and hopes for massive success in South America, and IBM was no exception. The region had a population comparable in size to North America’s. It had natural and mineral assets similar in volume and diversity. Nevertheless, the reality of 21 countries with French, Spanish, Portuguese, and English cultures, varying business traditions, and unstable economic and political circumstances made it impossible for U.S. corporations to achieve the massive growth they could in North America, but enough business existed that no major enterprise could ignore it. WT’s experience proved complicated for reasons largely unique to the region, but, as with Europe and Asia, its activities in Latin America were both about its actions and the company operating as an internationally integrated enterprise.

On January 1, 1959, Fidel Castro completed his six-year revolution in Cuba against the government of Fulgencio Batista. Just 33 years old, bearded, and wearing combat fatigue–styled uniforms, Castro seemed wild looking to middle- and upper-class Cubans and to the people IBMers sold to in Havana and in Santiago de Cuba. Their personal and professional situations deteriorated because, within months of gaining control, Castro announced his intention to run a socialist, then a communist, state. Within barely a month of taking power, his government began confiscating properties of wealthy Cubans, including private companies. Then, on August 6, 1960, Castro nationalized all foreign-owned businesses.

That action put Marcial Digat, IBM’s manager, out of business, because the company stopped operations, could no longer send products to Cuba, and now had Cuban employees who needed to leave the island for fear of being arrested as political enemies of the state. In the 1950s, he represented the company in Cuba, selling to government agencies, banks, insurance companies, and manufacturing firms. Prior to that, he had held important positions in the Cuban government. Like so many of his social class, Digat was suspected of being an enemy of the new state and so with just a few dollars to his name, he, his wife, Anita, and their children fled Cuba, leaving behind their home and possessions. Arthur Watson gave Digat a job in WT headquarters in New York. From that posting, Digat extracted other employees and placed them in various Latin American IBM offices. As one Latin American IBMer recalled, these Cubans “ended up having better jobs than what they had within IBM of Cuba.”35 Meanwhile, IBM was no longer selling data processing goods and services in Cuba.

Revolutions in Latin America disrupted routine business. Bigger challenges usually came in the form of runaway inflation that harmed IBM’s ability to extract its earnings out of a country. Brazil, so important to IBM in Latin America, chronically suffered bouts of stagflation or inflation and economic turmoil. Superficial reforms, lack of political will, and corruption made business there challenging. In 1990–1993, for example, Brazilian employees checked daily to see what the rate of inflation was and then determined whether to spend their money immediately to buy groceries, gas, or other items before they increased in cost over the next several days. How does a company pay its employees or charge customers under those conditions? Each financial crisis raised such issues across the continent and in the Caribbean.

Despite these problems, IBM’s activities in Latin America mimicked routines evident in other parts of the world. Its customers were large organizations that took delivery of IBM’s computers at roughly the same time as North American users, they just took fewer since there were fewer customers. Expansion in Latin America followed the familiar pattern of agents followed by local IBM companies. Branch offices opened in capital cities, then in other large urban centers. As WT expanded across Latin America, it opened regional offices to provide coordinated control and the kinds of resource sharing occurring in Europe and, through Japan, with other parts of Asia.

In the post–World War II period, both Watson Sr. and his son Arthur traveled throughout the region, meeting with employees, customers, and political leaders. They participated in IBM rituals such as 100 Percent Club meetings and Family Dinners. It was not always easy to carry out IBM’s rituals. For example, in 1950, Watson Sr. visited Bogotá, Colombia. As was customary, local IBM leader Luis A. Lamassonne prepared for his arrival. He explained, “We had already inspected the only hotel where we could hold the reception, the Hotel Estacion! We found it in complete shambles, and had to arrange to renovate and paint the dining room, as well as change all of the curtains.… We even had to buy the china that would be used.”36

In almost every country, national economies slowly evolved into forms that fit IBM’s profile for customers. Large enterprises and government agencies were core to IBM’s business in Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, Chile, and to a lesser extent also in Uruguay, Colombia, and Cuba. In each country, IBMers had cultivated business since the 1920s and, as that grew, they had established a local presence. By the early 1950s, IBM operated in Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, Costa Rica, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, Uruguay, Venezuela, Cuba, and all of Central America. Elsewhere, it had agents, such as in Trinidad, until it opened a sales office there in 1957. IBM set up a South American Area headquarters in Montevideo to play the same role as Paris and Tokyo. WT managed all of Central America as one region, and likewise with the Caribbean Area and the South American Area. At the height of 1401 sales, the South American Area established two regions, with the highly unimaginative names of Region One and Region Two. Region One consisted of Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay, while Region Two controlled Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, and Peru. Local managers who had came up through IBM led offices in countries and regions.

Sales of 1401s led to major growth in the 1960s. Local manufacturing of parts, and later machines, followed the same pattern as in Europe for the same reasons. Additional activities included manufacturing punch cards and electric typewriters. Just as IBM was getting ready to deliver S/360s, IBM Brazil was exporting to other Latin American countries parts and products valued at $1.8 million. IBM’s business grew along with its infrastructure. First came the 1401s, then S/360s (beginning in 1966), while the older product remained Latin America’s computer workhorse. IBM dominated its southern markets to the same extent it did in Western Europe.

As the number of branch offices, manufacturing facilities, service bureaus, and customer briefing centers increased, so did WT’s structure. On April 2, 1973, IBM launched a new organization: Americas/Far East Corporation (AFE), a wholly owned subsidiary of the company. In 1974, Ralph A. Pfeiffer Jr. (1926–1996) became its chairman. He worked at IBM for 37 years, starting as a salesman in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1949 and rapidly rising up the sales side of Domestic IBM. In 1970, he became president of the Data Processing Division, a highly prized job. He brought to AFE well-regarded managerial skills that helped him impose the same discipline and practices in the rapidly growing Latin American operations that had served IBM elsewhere. As Latin American business increased, so did the area’s presence in Corporate. In 1983, Pfeiffer became a member of the corporate management board, and the following year he became chairman and chief executive officer of IBM World Trade Corporation.37 Early in his management of AFE, Pfeiffer ran four regions in Latin America, Northern, Central, Eastern, and Western, mimicking names used for U.S. regions. He encouraged closer ties to North American operations, for example having customers visit U.S. operations. In 1977, AFE launched an educational tour for 30 Latin American and Asian educators from 24 countries to visit IBM’s research center, the T. J. Watson Research Center, nestled in Westchester County, New York, and universities in New Hampshire, Tennessee, and Florida.

IBM’s 4300 computers proved as popular in Latin America as in the United States and for the same reasons. PCs also did well, although they remained largely stand-alone systems without telecommunications until the 1990s. A litany of reorganizations throughout the 1980s and 1990s accommodated an ever-growing number of branch offices. Almost every year in the second half of the century, IBM opened up offices, manufacturing facilities, or education centers in Latin America. IBM had country general managers assigned to 20 nations by the early 1970s, all of them locals, managing thousands of employees, a population that expanded until the mid-1980s.

But not all went well. By then, local IBMers were complaining about “bureaucracy that continued to grow without limits.”38 Years after retiring, one Latin American IBM executive observed that in addition to the problem of bureaucracy, another had grown worldwide, not just in Latin America: “the arrogance of the Company amidst its grandeur”. In time, IBM paid a price for its problems, and not just in South America.39

RISING TIDE OF GLOBAL COMPETITION

IBMers looked at competition through several lenses. Corporate, sales, and product division headquarters had since the 1920s maintained staffs whose sole purpose was to learn as much about competitors as possible: product features, prices, contracting terms and conditions, customer attitudes, sales volumes, and who their customers were worldwide. Computer scientists, engineers, and product developers did the same, but with a particular eye on developing responses to competitors with better, faster, or less expensive products. Sales staff, the “field,” represented the third lens, the group that watched what was happening within their accounts. Normally, historians of IBM treat Corporate, Domestic, and WT solely in terms of the company’s strategy, such as how it leveraged national tax laws, drove down costs of manufacturing and marketing, and organized resources to have sufficient firepower aimed at entire markets worldwide. IBM, however, was a complex organization with different communities and regions that independently viewed competitive forces through their parochial lenses. Over time, however, the roles of WT, Domestic, and Corporate became more integrated, more monolithic, with respect to how IBM as a whole responded to a rising tide of global competition. As rivals scaled up to challenge IBM around the world, it responded with more integrated approaches to product development, pricing, terms and conditions, marketing, advertising, and sales. By the 1970s, WT increasingly functioned within that context of the behemoth.

When an industry observer, U.S. antitrust lawyer, or economist looked at IBM’s performance against the competition, they either viewed the number of times IBM faced competitors at the account level or at the top of the organization, where product pricing decisions were being made. They drew conclusions largely on those bits of information, but all segments and layers of IBM spent almost as much time worrying about actual or potential competitors as they did in understanding what customers wanted. It is a central observation about IBM’s culture, and no more so than for the years after the commercialization of computers, when so many types of rivals took on IBM. For that reason, all three spoke a common language, that of specific products versus those of rivals. While the higher up the organization one went, the more strategy and markets (hence market share) caught interest, all levels focused on two priorities: preserving the base of machines (hence current revenues) in every account and increasing market share. The definition of market share varied as one moved up and down the organization. At Corporate, executives talked about what share of all installed machines of a particular class IBM “owned,” such as mainframes (1950s–1990s), PCs (1980s–1990s), distributed processors (1970s–2000s), and so forth. WT thought in terms of how much of Germany’s IT “spend” went to IBM. At the branch level, it was all about how many competitors were kept out of its territory or how many competing machines were still installed that IBMers planned to displace. At that level and often at regional and division levels in sales, IBMers still knew by customer enterprise what competitors had installed, how long they had been there, often the enemy salesman’s name (not just the vendor firm’s), and exact terms of their offerings, and had plans for surmounting them.

As IBM increasingly used business partners for ever-larger products and accounts, it attempted to impose such competitive disciplines on them. This strategy yielded mixed results, as for example with minicomputers in the 1970s, PCs in the 1980s, and application software from the 1980s to the first decade of the new millennium. Mixed results arose out of the uneven performance of IBM’s partners and frequent rivalries with local IBM salesmen if their compensation terms did not clearly delineate who was responsible for specific types of sales. Nevertheless, business partnerships remained a tool used by WT, harkening back to a strategy used by Watson Sr.

One mechanism facilitating further integration of all parts of the company involved standardization of company-wide policies and practices, which spurred bureaucracy in the 1960s and 1970s. That meant there were employees whose primary job did not involve engaging with competition or whose objectives were seemingly in conflict with other parts of IBM battling competitors. By the 1960s, “marketing practices” departments approved proposed terms and conditions, such as pricing, that a salesman wanted to use against competitors. Often these departments said “no” because of some general rule or out of fear that if they gave in to one individual then “everyone” would want the same terms. Such a turn of events was seen as threatening IBM’s high profits across a product line.

Lawyers represented another class of employees often more concerned about aspects of IBM’s well-being than about competition, although when engaged in a specific customer situation they could be counted on to be helpful, especially those in a sales region or division. Lawyers working outside a direct sales organization might hold other views. For example, during the U.S. antitrust suit in the 1970s, lawyers counseled senior executives not to “own” more than 50 percent of any national market for fear that regulators would want to interfere. No self-respecting sales executive would ever want to obey such guidance; nonetheless, they heard it anyway. A third group—finance and planning (F&P)—might advise against an expenditure or a perceived affordability in order to control expenses or to implement a strategy to sustain a certain level of profitability, regardless of market realities.40 The influence of all three communities—marketing practices, “Legal,” and F&P—ebbed and flowed, depending on immediate realities. When American, Western European, and Japanese officials were concerned with IBM’s market dominance, lawyers held sway. When IBM dominated a market, marketing practices became more influential. When profits were under pressure, F&P played an increased role. It is remarkable, however, how so much of IBM’s culture and behavior had remained consistent worldwide from one decade to another since the 1950s. Responses to competitive pressures globally, nationally, and locally could vary as circumstances changed and new rivals came and went.

In Western Europe in the 1950s and 1960s, three types of mainframe rivals went after IBM’s tabulator customers: office appliance manufacturers, electrical device suppliers, and newly established computer firms. Many left the market when it became evident that the investment required to build computers, let alone go up against IBM, proved too rich for them or their home governments to fund. As business historians Martin Campbell-Kelly and Daniel D. Garcia-Swartz put it, “By the late 1940s, no other company in the world had developed a combination of capabilities that mattered for success in electronic computers as comprehensive as those of IBM.”41 The same abilities applied to events in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.42

By 1980, American rivals were operating in IBM’s non-U.S. markets, a new development. By then, the world was calling IBM “Big Blue,” while in the United States its rivals were pejoratively still referred to as “the Seven Dwarfs.” IBMers argued that they had scores of rivals worldwide in each market niche. By then, about 46 percent of all computers were installed outside the United States, evidence of a growing global market. As in the now large U.S. computer industry, valued at over $6 billion, additional billions were being spent worldwide. All this occurred prior to the arrival of the PC. Mainframe markets remained essentially the same worldwide in the 1980s as the PC platform rapidly infiltrated markets and customers.

Customers did not distinguish between World Trade, Domestic, or Corporate; IBM was simply a large U.S. firm. Global coordination of IBM’s operations increasingly attracted other large international corporations that also were integrating operations and thus appreciated IBM’s ability to provide coordinated account support worldwide through its Selected International Accounts (SIA) program. SIA managers in Switzerland told American salesmen what to do with respect to ABB, another in the Netherlands gave advice regarding IBM’s operations in Indonesia with Shell, an American in Detroit advised with respect to General Motors in Latin America, and so forth. Customers learned from IBM how to integrate their own globalized operations, while IBMers also learned from them.

However, we still face the question, what were IBM’s comprehensive responses to its growing list of rivals around the world? The answer to that question inserts us into the core of IBM’s global business strategy in the period from the 1960s to 1990 and the role of a new CEO.

FRANK T. CARY AND THE GROWTH OF A BEHEMOTH

By the early 1970s, in addition to focusing on rivals selling mainframes, plug-compatible computers, and leasing companies, IBM was also entering a new era. Thomas J. Watson Sr. was dead. Arthur Watson had resigned in 1970 and was soon followed by Tom Watson Jr. in 1971, the latter for health reasons. All of a sudden, there were no Watsons at IBM! The Old Man’s office at 590 Madison Avenue in New York existed almost as a shrine. In 1974, Arthur Watson fell down the stairs in his home and died of his injuries at the age of 55. His last few years had been sad, marred by alcohol abuse and a short-lived post-IBM tour as U.S. ambassador to France that ended after an incident on an airplane. No other members of the Watson family worked at IBM.

IBM’s senior executives had all come up in Watsonian IBM, with a heritage they applied through the 1980s, but the reality of their changed circumstances became evident when new people sat atop IBM’s throne: Vin “T. V.” Learson as chairman and, more importantly for day-to-day operations, the mild-mannered, gentlemanly Frank T. Cary (1920–2006) as CEO. Looking at what Cary’s generation accomplished contradicts myths that the U.S. government’s litigation against IBM in the 1970s slowed (or stopped) the company in its pursuit of worldwide revenues. Caution seeped into the company’s culture and behavior, but that was after a raft of lawsuits had been settled in the second half of the 1980s and early 1990s in the United States, not while lawyers were compelling IBM to spend tens of millions of dollars annually fending off competitors and government prosecutors. WT was not immune to IBM’s continued globalization, nor was its new CEO, who oversaw that transformation. Because IBM’s worldwide business grew substantially during Cary’s tenure as CEO, it is appropriate to discuss his role within the context of our review of World Trade and to emphasize that he was a global CEO, not focused only on U.S. operations. Observers of the IBM of the 1970s have ignored his broader role.

Figure 11.2

More than any other IBM CEO, Frank T. Cary turned IBM into a global behemoth. Photo courtesy of IBM Corporate Archives.

Cary lived through the era of the birth and diffusion of mainframes. He was in the thick of the rough-and-tumble battles that made the 1401 and then the S/360. Like so many of his generation, he came to understand the power of grand strategy as practiced by large multinational enterprises, especially regarding how IBM priced products, a secret he and a tiny coterie of executives learned from T. V. Learson and pricing experts in the central Hudson Valley of New York. It was perhaps more than ironic that the first long-serving CEO in the post-Watson era was not from the East Coast. Born in Gooding, Iowa, raised in Inglewood, California, and graduating from the University of California at Los Angeles, Cary went on to complete an MBA from Stanford University in 1948. That same year, he joined IBM as a salesman in Los Angeles. Cary rose quickly through the ranks from sales manager, to branch manager, and then, in 1964, to president of the Data Processing Division, which led the charge in selling S/360s in the United States. Two years later, he became general manager of the Data Processing Group, in effect running all U.S. sales. In 1967, he became a senior vice president. After two more promotions, in March 1971 he became a member of the company’s senior roundtable, the Executive Committee, and three months later was named president of IBM.

With this background, Cary knew about IBM’s competition and how to sell computers, deploy people, and allocate budgets. His most important midcareer duties involved selling S/360s. He learned about the product’s pricing dynamics at a time when the cost of computing was dropping so quickly that the technology was evolving into a commodity, creating a major problem waiting to blow up in Armonk’s conference rooms. Plug-compatibles and leasing companies were Cary’s crosses to bear. A quiet, efficient financial executive, Hillary Faw, responded to Cary’s request for insights in a note that in time U.S. antitrust lawyers flaunted as proof of IBM’s strategy for dealing with rivals, a memorandum that helped Cary pull back the kimono hiding useful strategic ideas that informed future management teams. Faw wrote that leading with prices and controlling them was key to IBM’s success:

IBM has established the value of data processing usage. IBM then maintains or controls that value by various means: timing of new technological insertion; functional pricing … refusal to market surplus used equipment; refusal to discount for age or for quantity; strategic location of function in boxes; “solution selling” rather than hardware selling.

The key underpinnings to our control of price are interrelated and interdependent.… These interrelationships are not well understood by IBM Management. Our price control has been sufficiently absolute to render unnecessary direct management involvement in the means.43

Some of these precepts were modified in the 1980s but not during Cary’s tenure.

Two years later, in 1969, the U.S. antitrust suit had begun, in time shaping what Cary did in the 1970s, but he already knew about the power of pricing, setting higher prices for computer memory upgrades when facing little competition while holding down the cost of mainframes, and of pricing disk drives using IBM’s own manufactured components, adjusting prices and configurations with new computers, just as Faw had argued IBM had done in the 1950s and 1960s. In other words, while sellers were selling, Corporate focused on pricing and configurations of equipment. Cary aimed his weapons at leasing companies in Europe and North America by cutting prices, charging for software that used to be free to customers of both leasing companies and IBM, and forcing lessors to lower prices even though both they and leasing customers had signed long-term contracts based on prior higher IBM ones. Midsized customers found their costs for computing dropping thanks to IBM’s pricing. When the price of S/360s dropped at the start of the 1970s, IBM killed off this product line, replacing it with S/370s that cost little enough to destroy demand for S/360s and charging for upgrades of memory and peripheral equipment larger computers called for. These actions came as demand for computing by new and existing customers was expanding worldwide.

Concerns regarding litigation in the United States and potentially in Europe also influenced how Cary and his executives reacted to competition. Worries about litigation hounded his generation, beginning before he was CEO, while IBM was in the thick of S/360 sales. How litigation influenced IBM’s relationships with competitors is illustrated by the firm’s unbundling decision in 1969. In 1968, IBM faced antimonopolistic lawsuits in the United States filed by competitors. The U.S. Department of Justice was pressured by them to sue IBM, most aggressively by CDC. As a preventive action against possibly losing cases, IBM explored unbundling software; that is, charging customers for some software and other services while offering lower leases for hardware to smooth out the total costs to users. That strategy would allow leasing companies to sell machines to customers and possibly take the air out of a potential federal case and possibly private lawsuits in Western Europe and Japan. It is an important point because historians of IBM’s unbundling decision described it as an American event, but by the end of the 1960s, all pricing and product strategies in the company were weighed against broader considerations of a global market.

In mid-1969, IBM announced unbundling, to begin January 1, 1970, drawing the attention of customers and competitors worldwide as they pondered the implications of this change in software pricing. While designed mostly as a response to U.S. litigation circumstances, IBM’s international ecosystem took note, especially large multinational customers with data centers outside of the United States that coordinated with IBM on a global basis. Meanwhile, U.S. customers thought IBM had not done enough to even out costs, that hardware prices had not dropped sufficiently to compensate for what they now would have to pay in total. Competitors, too, were not happy, arguing that IBM had not done enough to open up markets for them. Unbundling failed to dissuade the federal government from pursuing an antitrust case against IBM, discussed in detail in chapter 12. IBM made no immediate profit on the deal, as its costs for developing software were already sunk so they could not quickly be recovered, because software was to be leased, not sold. The industry entered its first global recession in 1970–1971. Burton Grad, a member of IBM’s two task forces that prepared the details of this announcement, recalled that “IBM acted from fear that antitrust actions against it would succeed because of IBM’s previous discriminatory bundling of services with computer products,” with unbundling designed to mitigate this problem, IBM “acting in its own, primarily defensive self-interest when it unbundled.”44

Pricing, litigation, competitive pressures, an international economic recession, and now customer expressions of opinions about how IBM should offer all manner of products and services complicated decision making for Cary and his senior leaders. Cary had learned that problems required varied and continuous fixes, that pricing strategies were never enough, no longer the silver bullets they seemed a half decade earlier. Too many circumstances had changed quickly, and Cary had to do more.

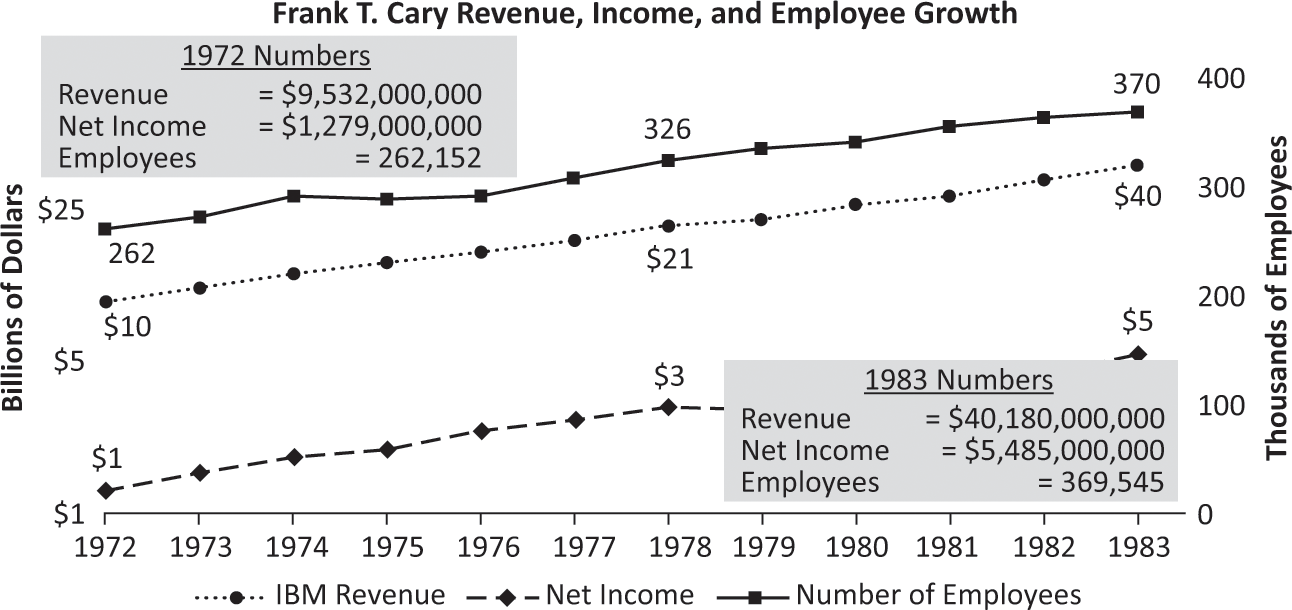

To set the scene, Cary became CEO in 1973 and ran IBM’s operations until 1981, a fact that is a bit confusing, as he was also chairman of the board from 1973 to 1983. He held all the global reins of power and control, even though, as in any large corporation, he still needed to persuade other executives to go along with his ideas, and he still relied on task forces to work up the details on an issue and make recommendations. Nevertheless, he could look at the entire world and think about how to play IBM across the map. Even Tom Jr. had only some of that power after his father died, as he had to share it with his brother. Cary had a worldwide operation up and running. WT was real, with organizations, factories, branch offices, and experienced IBMers on the ground. Not since Watson Sr. had so much authority been invested in one person. Even then, the “Old Man” never ran a company as big as the one Cary was running. In 1973, Cary had over 150,000 employees in the United States and another 120,000 around the world. That year, IBM generated almost $11 billion in gross income and net earnings of nearly $1.6 billion. When Cary retired in 1983, the company had almost 370,000 IBMers, generating over $40 billion in revenue and $5.5 billion in net earnings.45

At the beginning of Cary’s tenure, it was not clear that he would be the strong leader to follow Watson Jr. or could push forward a large, bureaucratic organization. One knowledgeable computer industry watcher, Ernest von Simson, sided with the doubters, but decades later, when reflecting on those times, concluded that, “All of us were wrong. Frank Cary was the first professional manager to head a traditionally entrepreneurial company that had outgrown its traces. His style may have been more modest than [that of] his predecessors.” He was not flamboyant.46 Watson Jr. agreed: “The fact was that for eight years he ran the company as well as it had ever been run.”47 Cary epitomized the “Organization Man” of his time.

His first challenge concerned the leasing companies gaining on IBM, since their ability to sell secondhand equipment at lower cost constrained IBM’s ability to charge higher prices, threatening the controlled revenue and profit growth IBM so cherished. Cary had already experienced rounds of meetings over several years before the S/370s were introduced, internal battles and “non-concur” blocks to one form of technology or other, and considerations of various strategies. IBM documents made public in lawsuits from the period recorded his frustration. For example, Cary wrote Learson on November 5, 1971: “Organization indecision was intolerable.” So it went, with other memos expressing annoyance in the months ahead.48 Cary advocated introducing less expensive S/370s in response to competitors, even if it meant taking a short-term hit on revenues and irritating customers who had installed early S/370s. He got his way. Customers in the early 1970s swapped out their 370 Model 155s and 165s for replacements sooner than they had planned. Leasing companies were stuck holding warehouses of these now technologically obsolete systems, which dropped in value by 20–40 percent from their original purchase price. They did not learn their lesson and came back in the mid-1970s, leasing the new Models 158 and 168. Cary & Co. again introduced new computers and peripherals at lower cost and with new features, again chasing off leasing companies in Europe and North America.

But Cary knew IBM’s process for introducing products was deteriorating. Every S/370 decision proved cumbersome, slow, and risked not being made in time to counter rivals. Senior sales executives feared salesmen were losing control over their accounts. In the 1970s, the game was turning on who had the least-expensive machines, a change from the 1960s, when it was all about price/performance. Cary pushed for resolution of a number of problems a task force had identified in 1971: a broken product-planning process, “complexity” emanating from IBM and its rivals, not to mention a growing variety of “vested interests,” software development (now a profit center) at odds with the hardware divisions (also profit centers), quality of the staffs involved, and too much interference by senior executives. The task force even blamed Learson by name for too much meddling, a breach of company etiquette but obviously necessary to call out. Cary chose to decentralize operations to speed IBM’s response to changing market conditions.

On January 13, 1972, Cary split the Data Processing Group in two, with sales, maintenance, and planning in one part and components and software product development in the other. He named the first cluster the Marketing and Services Group, the second the Data Processing Product Group. John Opel, Cary’s future successor as CEO, took charge of the second group. A third organization, the General Business Group, focused on smaller customers, while the existing Office Products Division sold typewriters and other word processors. However, this reorganization created a problem that lasted through the 1970s. Customers were now being visited by Data Processing Division sales staff for large systems while salespeople from the General Business Division called on them for midsized ones, sometimes in competition for the same business as DPD’s, and, of course, the typewriter salesmen from OPD called on them as well. Customers worldwide complained about this problem for a decade. Cary had created three vertically integrated groups essentially autonomous of each other. His decisions had little to do with lawsuits or the antitrust case. They were about responding to rivals around the world.

The organizations created by Watson Jr. were hardly recognizable. Big breakthroughs with systemwide products were no longer relevant. Now IBM faced worldwide markets where it had to compete for every piece of business while costs of computing (e.g., computer chips) continued to decline. Introductions of technology would be done in an evolutionary, incremental manner. In May 1975, Cary took the extra step of reorganizing the specialized business units into self-sufficient product divisions. For example, software came under control of the product divisions. Bob Evans, long IBM’s advocate for technological compatibility across systems, left his job, replaced by Allen Krowe (b. 1932). Krowe was a high-energy financial executive who later served as IBM’s chief financial officer in the early 1980s, when he was credited with inventing the euphemism “negative growth” to put a positive spin on poor financial performance. Subsequent reorganizations slowed advanced product planning activities, while mainframe development was split into two parts: one to produce products to compete against Amdahl and Japanese rivals, the other to compete against minicomputers. Jack Kuehler (1932–2008), another engineer who in the late 1980s served as president of IBM, led the latter. An IBM observer in 1978 summed up the situation: “IBM is now in the box business, not total systems,” because “we can’t afford the delays, confusion, lack of software accountability, and endless coordination it takes to deliver total systems.”49

Setting aside potential antitrust consequences, the new decentralized organizations attacked their competitors with what can only be described as a blizzard of product announcements in the late 1970s and early 1980s that seemed to appear almost monthly or quarterly, including the iconic IBM PC, discussed later. To clarify who IBM’s rivals were, there were four types: manufacturers of plug-compatible mainframes; a growing collection of vendors selling plug-compatible peripheral equipment; leasing companies, which ranged from one-man operations to nationally based financial companies; and scores of minicomputer suppliers. This competitive landscape remained unchanged in the 1980s. By mid-decade, IBM encountered a fifth rival: PC-compatibles, such as Compaq. Apple, already active, was a minor player at the time.

In January 1981, having reached the customary retirement age of 60, Cary stepped aside from day-to-day operations. The board of directors replaced him with John Opel as CEO, while Cary stayed on as chairman for two more years and as a member of IBM’s board for ten more years. During his tenure as CEO and chairman, he had decentralized product development and midwifed IBM’s PC, introduced in August 1981, and had grown the company (figure 11.3). Cary should be remembered for hammering plug-compatible rivals and leasing companies, too, although they never went away. Amdahl, for example, periodically infused with new funding from Japanese investors, continued to needle IBM’s mainframe business into the 1990s.

Revenue, income, and employee growth under Frank T. Cary, 1972–1983. Courtesy of Peter E. Greulich, copyright © 2017 MBI Concepts Corporation.

Opel quickly focused on competition. Articulate and methodical, he, too, had come up in U.S. sales in a career that paralleled Cary’s. Thanks to IBM’s strategies, thousands of rivals had either gone out of business or consolidated into fewer, more muscular ones requiring new responses. The new names that kept appearing on competitive analysis reports in the 1970s and early 1980s included DEC, H-P, Wang, and, by the mid-1980s, a raft of PC rivals, notably Compaq. Opel consolidated operations to drive down costs and increase focus. He established three major entities: large computers, midsized ones (he put PCs in with this group), and all field operations. He dissolved specialized units, such as those selling typewriters (Office Products Division) and General Systems, which had sold a new distributed minicomputer called the S/1 as a quick, if anemic, response to rising mini competition.

Senior leaders were of Opel’s generation, notably John Akers (1934–2014), a future CEO of IBM who had come up in sales the same way as Cary and Opel. Akers took over the midsized computer and PC pieces of the business and brought Krowe over as his vice president of finance. Kuehler now led the mainframe computer business, while “Buck” Rodgers managed sales and support. The Data Processing Division had been restructured into the National Accounts Division (NAD) to provide sales coverage for IBM’s top 2,200 accounts. Smaller accounts were put into the National Marketing Division (NMD). Opel named George Conrades (b. 1939), a Hollywood handsome, dynamic, and polished sales executive, to head up NAD. For a short while in the early 1990s, Conrades competed against Akers for the top job at IBM. Like Rodgers, he was highly regarded by IBM sales organizations around the world.

The U.S. antitrust suit concluded in early 1982, soon after Opel’s appointment. The 4300 mainframes were competitive, doing what the 1401s had earlier, expanding the base of new accounts and users within existing accounts. Sales of PCs were doing well, so Opel reverted back to IBM’s old practice of setting controllable annual growth targets of 18 percent. Things looked fine, but quickly the product divisions again began creating incompatible products that often proved uncompetitive. These included minicomputers and, later, newer models of PCs. As Simson wrote, “It was creativity run amok that would bedevil John Akers a decade later.”50

To expand business and continue hammering the intrusion of small and large competitors, IBMers, particularly those in NAD, focused on expanding their footprint within existing large accounts. While they tussled with plug-compatibles in the “glass house,” normally controlled by an MIS director reporting to the CFO, IBM’s sales force began calling on other departments. These included engineering, factories, and distribution centers, leveraging their growing industry knowledge to sell new applications. They taught “end users” how to apply computers to improve operations or to lower labor costs. IBMers had become captives of the management information systems (MIS) directors in glass houses who did not want them drumming up new business that would bring more work to them, while IBMers felt compelled to break away from these data processing directors who threatened to do business with plug-compatibles. Most customers continued to use IBM equipment. While only a third of all business opportunities in IBM “glass house” accounts were contested (this was more common with end users), that was still a large number for a company that wanted “account control.” Opel, and later Akers, retrained field staff to sell applications; the approach worked. IBM’s revenue kept growing. In 1984, IBM had 405,000 employees worldwide. Its high-water mark came in 1990, after a decade of continuous growth, culminating in nearly $69 billion in revenue and almost $6 billion in profits, but with a smaller population of employees, because it was already feeling the pinch of declining business and margins, so it ended the year with 373,000 workers.51

Executives worried about the surge of Japanese imports into the United States, but with no radical changes anticipated in technology, it seemed IBM’s existing pricing strategies remained effective. Between the 4300 and IBM’s PCs, revenue grew rapidly in the early 1980s, jumping from $29 billion in 1981, Opel’s first year at the helm, to $46 billion just three years later. It seemed to employees, customers, competitors, and the business press that IBM could do little wrong. It was a darling of the stock market and often the number one company on anyone’s list, but the future was being compromised. To increase revenues when computers were still dropping in cost, IBM decided to shift from leasing equipment to encouraging outright purchase of its products. IBM increasingly favored the earlier, larger cash infusion that resulted from outright sales, weaning itself off the leasing business model it had embraced for over 90 years. In exchange for that shift, IBM lost the predictability of cash flows that came from leases. The sales organization worldwide disapproved of this change in strategy. Conrades & Co. even had to entice the field with bonuses to sell rather than lease products. Leasing companies could buy a flood of secondhand equipment by the end of the decade, which they could lease to IBM’s customers in competition with the company’s new products. Another cost to IBM involved the decline of account control as long-term relations greased by the lock of a lease on both IBMers and customers declined, transforming relationships into transaction-based ones rather than the more collaborative services-centered relationships of old.

History likes to blame Akers for IBM’s decline and near death, but IBM caught the deadly infection in Opel’s day. Because the largest competitive battles still occurred inside the glass house over mainframes and peripheral equipment, salesmen, and their leaders in the corner office of the CEO, focused more attention on these aspects of the business than on PC sales or other opportunities. It seemed to many employees that IBM was running on autopilot. Akers succeeded Opel as CEO in February 1985, and his story will be told later, since he is credited with single-handedly nearly destroying IBM, resulting in his firing in January 1993. However, we are getting ahead of our story, because we must first understand how going global during the Watson Jr. and Cary years affected IBM, contributing to the malaise Akers confronted.

IBM had become so large by the end of the 1960s that it kept growing seemingly in a world of its own making. It had its own vernacular, processes, and rules for everything, and its customers were largely cocooned within IBM’s technologies and technical standards. Competitors could not scale up. Governments the size of Great Britain’s, France’s, and Germany’s could not assist their national champions, with Japan being the exception. While Latin Americans did not see IBM as a threat to their economic survival, with the muted exception of Brazil, in Europe more IBM equipment was already installed. A handful of IBM corporate managers could make decisions affecting whole nations. Perhaps the most interesting example is what happened in India.

IBM LEAVES INDIA, THEN RETURNS

In the 1950s and 1960s, India was one of the world’s largest poor countries. Its industrial base looked more like Europe’s of the pre-1860s, and its use of data processing equipment remained minimal. After gaining independence from the British in 1947, it followed the Soviet model of building up heavy industry, resulting in growth of the local economy of about 3.5 percent each year, while its population expanded faster. Famine always seemed a threat, and poverty the nation’s hallmark. The national government had committed itself to socialism, implemented through autarkic practices. This was not good for U.S. companies like IBM, which functioned best in open market economies.

The Indian government wanted to leapfrog economic and managerial phases nations went through to apply the kinds of advanced technologies represented by computers and other industrial equipment. In the mid-1960s, the government accused IBM of dumping old 1401s into India instead of making available the new, more sophisticated S/360s. Local task forces called for India to become self-sufficient in supplying the nation’s computer needs. One study, prepared by the Bhabha Committee, laughably suggested the nation’s entire needs could be met with an investment of $4.2 million on the latest technologies, but, in 1967, its recommendations became public policy. The committee failed to account for the lack of local computing skills, experienced managers, and even business conditions that could benefit from computers.

One by-product of this naive approach to computing hit IBM hard. Indian regulators came to IBM in the late 1960s to discuss sharing part ownership of IBM India with local investors. It was not a new idea; European governments had broached that possibility, but IBM turned them away without hesitation. IBM’s executives, both local and those from New York, turned down India’s proposal, arguing what turned out to be the truth of the matter. They told the Indians that IBM managed a worldwide, integrated product development and manufacturing process. To make that process work, it had to manage in a centralized fashion, and IBM was organized around that construct. To divert some of IBM’s control to a local IBM company’s operations by selling off part ownership would compromise the efficiency of that process. IBM executives believed that argument so much that they were prepared to do the unthinkable: walk away from the second-largest country in the world. As talks continued in 1968, executives warned they were prepared to exit if necessary. The Indians backed down.

Indian officials had also been talking to other companies, and the British company ICL caved in. It agreed to allow an Indian-owned manufacturing plant, as it did not have a highly integrated worldwide manufacturing process comparable to IBM’s. In those years (1968–1972), the Indian government failed to wrest control of its tiny computer industry from foreign companies; it had no indigenous industry yet. Perhaps two locally built systems had been sold in India, while another 185 came from other countries.52 India wanted foreign companies to manufacture locally, which foreign manufacturers resisted. Instead, some decided to bring in older products, much as IBM did with 1401s. IBM’s practices meant India would not get the latest technologies, such as IBM’s S/360s and later S/370s, which IBM, and India’s actions, blocked from coming into the country and would prove too expensive for local customers anyway.

IBM’s position did not stop the Indians. They came back to IBM in 1973 and again in 1974, raising the same issues. Both sides talked into 1978, with neither budging. At most, IBM offered to manufacture small things locally, such as typewriters. Both local and WT IBMers still did not feel the Indian market could absorb modern equipment such as S/360s, more realistically now S/370s, because the logical candidates for such systems had little or no prior experience with computers. Most railroads, all government agencies, and banks, for example, still choked on paper, while labor was so cheap that few incentives existed to automate their work. The business case to motivate IBM to act differently was simply not there. IBM’s corporate records demonstrated that the IBMers were adamant that the Indians would not know what to do with an S/360 or S/370. As yet, no case existed for perhaps building them there and exporting them to other parts of Asia, which, in the 1970s, were just as incapable of using this technology as the Indians were. It all came to a head in 1977, with officials pushing hard on the matter. Meanwhile, whatever business IBM had going on in India had come to a halt, as everyone waited to see the outcome of the talks. Permits to import IBM equipment stopped being issued. Other U.S. and English companies slowed their activities. Burroughs, to avoid that trap, negotiated an alliance with Tata for shared ownership. It made little difference.

Lost in all the discussions, except to the IBMers in WT, was the size of IBM’s Indian market. It was tiny, so IBM had little incentive to break its worldwide policy of not selling equity in a local company. Furthermore, if it did it here, it would have to in France for sure and also in other countries. Its last order in India for equipment had come in December 1974—three years earlier. Rental and other revenues hovered at only $6 million annually from all of India. The staff used to refurbish machines totaled 219 IBMers. In all of India, IBM had 803 employees, less than the number they had in a midsized U.S. state or midsized European country. In fall of 1977, WT staff figured out how to pull out of India if the government persisted in its demands. Indian officials felt IBM’s presence would impede development of a local industry, while IBM focused on the issue of ownership. They were talking past each other.

In New York, WT staff told senior management that IBM had in India 362 data entry customers, 479 unit record equipment users, and 139 computers (1401s). The grand total of all machines was 7,881, with a net book value of just $5.6 million that could be sold off. This information convinced WT management that they could dispose of the inventory, stop supporting it, and walk away with no measurable impact on the corporation’s balance sheet.53 When the staff calculated severance packages for local employees should they choose to stay, travel and moving costs for those wishing to remain with IBM in other countries, and other related expenses, these totaled $5.9 million. In other words, IBM could walk away from India at a cost of $300,000. When negotiations broke down in November 1977, IBM announced it was leaving, and the following June it did so. The Indian government felt it was best for that to happen so that the Burroughs-Tata and other potential start-ups could thrive, including a local national champion, Electronics Corporation of India Limited (ECIL). Quickly, other firms formed, including one made up of local ex-IBM employees, International Data Machines (IDM).

This is a remarkable story on many levels. India developed a local computer industry, although it remained small, largely for the same reasons as at IBM. IBM was able to demonstrate to any government that cared that it would not break up its organization, while its integrated product development approach remained intact. Employees who chose to leave India were assigned to similar jobs in Australia, Canada, Great Britain, and the United States, continuing the normal progression of their careers. The Indian episode gave us a view into how IBM analyzed situations and “staffed out” issues before making decisions. The story also pointed out that senior managers could tightly operate globally—an objective Cary wanted and that Opel supported—and also that they could not afford to act otherwise. IBM had become a global behemoth, with the good and bad that came with such a distinction.

When the announcement went public, there was of course much buzz worldwide, but not at World Trade headquarters. IBM’s media machine defended the decision, and other large corporations took note. The global power of IBM made it comfortable for U.S. executives to look at the world’s map and pick and choose where to participate. In the 1990s, IBM returned to India after the government gave up its socialist economic practices and welcomed back foreign corporations. By the early years of the new millennium, IBM had a couple of thousand Indian employees, and by the early 2010s, over 100,000, or 25 percent of all people working for IBM worldwide.

Obvious losers in this story were potential customers who needed IBM’s training and services style of selling used worldwide so effectively for decades in introducing thousands of organizations to every generation of new data processing. One global study of the diffusion of computing demonstrated that where IBM operated, local organizations acquired more computing earlier than in nations in which IBM did not have a presence. The pattern held regardless of the role IBM’s competitors played.54 India’s expenditures on computers in the 1980s were just slightly more than those of the Philippines and Indonesia. Taiwan spent more than India as a percentage of its national economy as late as the early 1990s. India’s computer takeoff waited until the last decade of the century.

HOW GLOBALIZATION CHANGED IBM

As WT expanded, what were the effects on IBM’s culture? To help answer that question, we have the results of Geert Hofstede’s opinion surveys conducted in 40 countries between the late 1960s and early 1970s. Because many of the issues he explored as an IBM personnel manager did not change over many years, we can accept that his findings reflected circumstances early in the 1960s and later in the 1970s.55