7 HOW CUSTOMERS, IBM, AND A NEW INDUSTRY EVOLVED, 1945–1964

[T]he computer was a blazing white-hot nova in the marketing heavens and the once ubiquitous accounting machine was a fading red giant destined to grow dimmer by the year.

—WILLIAM W. SIMMONS1

FOR OVER FOUR decades, historians discussed whether IBM was early or late to the computer market. The epigraph by an IBM sales executive, William W. Simmons (1912–1997), was immediately followed by another observation: “But in 1958 this understanding and acceptance by IBM management was still several years in the future.”2 Thomas Watson Jr. admitted as much when reflecting back on the quality of IBM’s computers during the last few years of his father’s reign and the early period of his own during the 1950s:

Technology turned out to be less important than sales and distribution methods. Starting with UNIVAC, we consistently outsold people who had better technology because we knew how to put the story before the customers, how to install the machines successfully, and how to hang on to the customers once we had them.3

Others could introduce a new product, and if it took off, IBM played a fast game of catch-up. If it was too slow, it missed the bulk of a new market, but it usually could catch up and exceed the competition, just as it did with the printer-lister. More insightful was that Tom Jr.’s comment about the UNIVAC could as easily have been made about IBM’s performance in 1917–1922, and even in the 2010s, as when the company again played catch-up, this time with cloud computing. Ultimately, the argument seems esoteric, because historians agree that IBM proved enormously successful and that it dominated the computer market with shares of between 40 percent and 80 percent in one country after another.

The critical issue is, how did it do that? How did IBM become the largest, most important computer firm? The answers to these questions are crucial for a number of reasons. First, private enterprises are in business to generate revenue and profits, and, to protect them, they expand their market share. Second, other firms not yet behemoths in their industries are eager to learn how others did it before them. Third, in a world in which economies are managed as much by public officials influenced by the thinking of economists and business school professors as by laws, knowing how a company prospers is more important than whether a firm was early or late to market. By the end of this chapter, it should be clear that IBM was well on its way to becoming an enormously successful vendor of computer equipment. Subsequent chapters lay out the case for how that happened, a presentation begun in chapter 6 and broadened in this one.

The seeds of IBM’s success came from two sources. Steven W. Usselman’s observation that IBM was constructed out of the right skills and organization needed to enter this industry—a point we can apply to its tabulating equipment phase, as early as the 1910s—suggests the first one. A second source is the sales and corporate culture that made it possible for IBM not to be shy about engaging with new technologies and circumstances. As the company became larger and affected operations of an increasing number of customers, the complexity of the explanation for IBM’s success did also. In this chapter, we demonstrate that reality by examining three topics: the role of customers in IBM’s early computer business, IBM’s participation in the creation of this new market (the computer industry), and finally, as in earlier chapters, the company’s performance, which we assess by looking at its business results. Permeating the narrative is the extension of more forms of coordination and collaboration within the company and across its market ecosystem.

These questions and the supporting organization of this chapter leave open the question that often attracts students of the company: the role of the Watsons. Rowena Olegario is typical in giving the two Watsons enormous credit for the success of IBM, and indeed this book does, too.4 It also took many people, numerous strategies, and multiple product innovations to make the story of IBM, in the words of historian Thomas K. McCraw, “epic in the business history of the United States,” strong words from a sober scholar. Yet McCraw also gave much credit to Watson Sr.5 Here, we tell a far more complex story that makes clear that the Watsons, while a necessary component of IBM’s success, were not the whole of it. Because they were present, we cannot imagine the company having succeeded the way it did without them.

CUSTOMERS AND NEW COMPUTERS

By 1956, barely a half decade into the computer business, IBM had 87 computer installations and another 190 systems on order. IBM’s rivals combined had 41 installed and another 40 on order.6 Those statistics did not include several thousand tabulating machine users scattered around the world, all of which Corporate saw as potential future customers for computers. By 1960–1961, the world had 6,000 systems installed, over half of them from IBM. Customers rapidly demonstrated interest in these “giant brains” and talked among themselves, often one data processing manager to another, leveraging introductions to each other by vendors and through industry organizations, such as SHARE, discussed further here.

These customers articulated to IBM and other vendors what they wanted. Conversations began among engineers and scientists inside and outside of IBM. Initially, IBMers did not initiate these discussions; however, they increasingly became involved either as individuals or as representatives of IBM. Recall the Moore School lectures after World War II. Academics established journals, such as the Mathematical Tables and Other Aids to Computation (established 1943), Digital Computer Newsletter (1948), Computers and Automation (1951), and the Association for Computing Machinery Journal (1954). Commercial publications appeared also, such as the respected and well-distributed Datamation (1957) and IBM’s IBM Journal of Research and Development (1957) and Computer Journal (1958). Noncomputing trade press and business magazines explored the role of computers on both sides of the Atlantic in the 1950s and worldwide in the 1960s. Industry trade journals carried articles inspired by vendors or on early user experiences with computers. No industry seemed exempt from the exercise.

During the 1950s, accounting, manufacturing, process, public sector, and other industry organizations published hundreds of articles describing how people used computers and the benefits gained, a number that would expand to tens of thousands in the following decade. These associations hosted seminars and other training events at national and regional meetings. Computing was a “hot” new business topic, while accounting auditors fretted about whether they could track transactions on computers, where the only paper trail was what entered or came out of a computer, not what was going on inside one. Cuthbert Hurd observed that one of the biggest selling problems IBM faced in the 1950s was educating potential customers about using computers.7 Salesmen and their managers also had to go through the same learning curve.8 To be clear about the matter, business managers needed the education that Hurd referenced, as did data processing managers engaging with computers for the first time. The closer a potential customer was to the technology, the more likely they were reading technical literature and discussing issues with peers.

As the number of users of tabulating and computing machinery expanded, a community of several thousand managers developed to deal with electronic data processing in the United States and roughly half as many more in Western Europe. In the United States, they did what other professions had long done: they organized themselves into “user communities,” mostly aligned by computer vendor, and gathered at annual conventions to present to each other their experiences using specific computers. They bragged about their successes and met with vendors to inform them of problems and opportunities, much the way automotive or motorcycle clubs do today. These were important opportunities for IBM technologists to discuss their projects and to collect insights on the performance and needs of their systems.

Of these groups, one of the most important was SHARE, meaning the word share, as in sharing information about IBM products. Users of IBM 701s in the Los Angeles area established the group in 1955. By the mid-1960s, it had become the most important of these user groups, made essential by all the technological changes occurring. Run by volunteers, not IBMers, it set the agenda for meetings. The group discussed every form of IBM technology: computers, peripheral equipment, operating systems, programming languages, other utility programs, database management tools, and other software. SHARE published reports, hosted conventions, and expanded. By the early years of the new millennium, it had over 20,000 members working in 2,300 organizations, all of them IBM customers.

There were other organizations, more broadly based, that included users of equipment from vendors other than IBM. Of these, the most important was the Data Processing Management Association (better known as DPMA). Founded in 1949, its members focused on managerial issues, while SHARE focused largely on technical considerations. Both shared information. DPMA still exists as the Association of Information Technology Professionals (AITP). DPMA was where data processing managers most frequently made presentations about their use of this technology. Manufacturers were particularly active from its earliest days, with members publishing case studies in annual DPMA proceedings and in their own trade publications. David R. Clarke was typical of his generation. A vice president at Johnson & Johnson, he presented a paper at APICS (American Production and Inventory Control Society, founded in 1957), a major manufacturing trade group keenly interested in using computers, about production planning in his company, in which he described how he used computing. That was in 1964, looking back on over a decade of experience with computers.9 As early as 1954, others were commenting on computerized production planning in industry trade journals, such as Electrical Manufacturing.10 Cases and presentations became a flood of publications by the early 1960s.

While IBM sales reps always talked to customers, factory workers, with the exception of those who were literally constructing machines, also interacted with customers who toured factories and wanted to chat with employees. It became routine for visitors to pose for photographs next to the computer being constructed for them, accompanied by the actual workers involved. A sign hung from the ceiling with the name of the company or agency for which a particular machine was being assembled. Employees shared information, insights, and opinions with customers in offices, conference rooms, and in visits to customers’ plants and classrooms.

Such discussions proved helpful, if sometimes contentious. Recall the case of whether to use cards or magnetic tape in the 1950s. Customers embraced tape before IBMers did, seeing its advantages in storage, reduced space, speed of operation, and reduction of manual operations. A million binary digits stored on tape took up one cubic inch of space, compared to 500 cubic inches on IBM cards, using 3,000 cards.11 As early as 1948, Jim Madden, vice president responsible for computing at Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, told Tom Watson Jr., “Tom, you’re going to lose your business with us because we already have three floors of this building filled with punch cards and it’s getting worse. We just can’t afford to pay for that kind of storage space. I’m told we can put our records on magnetic tape.” Tom Jr. recalled that Roy Larsen, the president of Time Inc., said the same thing: “We have a whole building full of your gear. We’re swamped. If you can’t promise us something new, we’re going to have to start moving some other way.”12 Metropolitan Life used both Univac and IBM computers. Madden was the typically knowledgeable customer who since the 1890s had routinely influenced what products IBM had introduced. Tom Jr. learned as much from customers as from IBMers, saying, “You’ve got to feel what’s going on in the world and then make the move yourself.”13 By the mid-1950s, customers were confident, empowered, and made sure IBM understood their needs.

A NEW IBM AND THE EMERGENCE OF A COMPUTER INDUSTRY

On June 19, 1956, IBM’s world stopped turning for a moment. Thomas J. Watson Sr. died. The word spread quickly through all of IBM’s facilities around the world, the press reported the news, and even customers were stunned: An IBM without Watson Sr.? It seemed momentarily inconceivable. Watson had been the “Old Man” for so long that hardly anyone remembered what he looked like as a young man. He had run IBM for decades. He was never going to die, but when he did, the New York Times published the longest obituary it had ever written. It called him “the world’s greatest salesman” and noted that “to a great extent, the International Business Machines Corporation is a reflection of the character of the man who led it to a position of eminence among the business machines manufacturers of the world.” Equally obvious to many at the time, the piece continued, “From the slogans that adorn its walls in eighty nations … by which it introduces recruits to what may be called the I.B.M. way of life, the company is the creature of the man who commanded it for forty-two years.” Watson took a small group of companies “to a position so akin to a monopoly that competitors and Government antitrust officials hauled it into court.” The newspaper captured the essential element of his thinking, that “habitually he saw nothing but the best of days ahead.”14 He was a force of nature. In the process, he changed how companies and government agencies went about their work. On his watch, IBM entered the computer business.

Historians looked at him with a more critical eye, although their view was not fundamentally at odds with the accomplishments celebrated by the New York Times. In a survey of business historians published in 1971, they ranked him ninth in importance, in the company of the likes of Henry Ford (#1), Alexander Graham Bell (#2), and Thomas Edison (#3), and just before George Eastman (#10). Thirty years later, in another survey of business historians, he ranked eleventh, while the top three were Henry Ford (#1), Bill Gates (#2), and John D. Rockefeller (#3).15 Such lists suggest the value placed on managerial acumen and entrepreneurial results, two areas of considerable interest to historians in recent decades. Watson’s biographer Kevin Maney emphasized his intense desire for respectability, personally and for IBM.16 Watson was a superb salesman who intensely went about his work. He was so optimistic that, as Richard Tedlow suggested, his activities entailed risks, such as when he put the fate of the firm on the line in developing new products at the start of the Great Depression.17 As Tedlow and I have independently argued, luck, too, played a crucial role in his career. Historian Steven W. Usselman reminds us that “the key question raised by the entire genre of business biography” centers on one fundamental question: “How do the personalities of business leaders influence the firms they lead?” In the case of Watson Sr. and IBM, the answer is a great deal for a long time. In future chapters, we will see his shadow cast over IBM for well over two decades after his death, propelled by the culture he created and his use of nepotism to keep Watsons at the helm. But it, too, faded over time, as Usselman explained, because “the links between personality and enterprise grow much more muddled and complicated, however, as the size of the firm increases and its range of activities expands.”18 Whatever one wants to think about Watson Sr., he left the company in good shape.

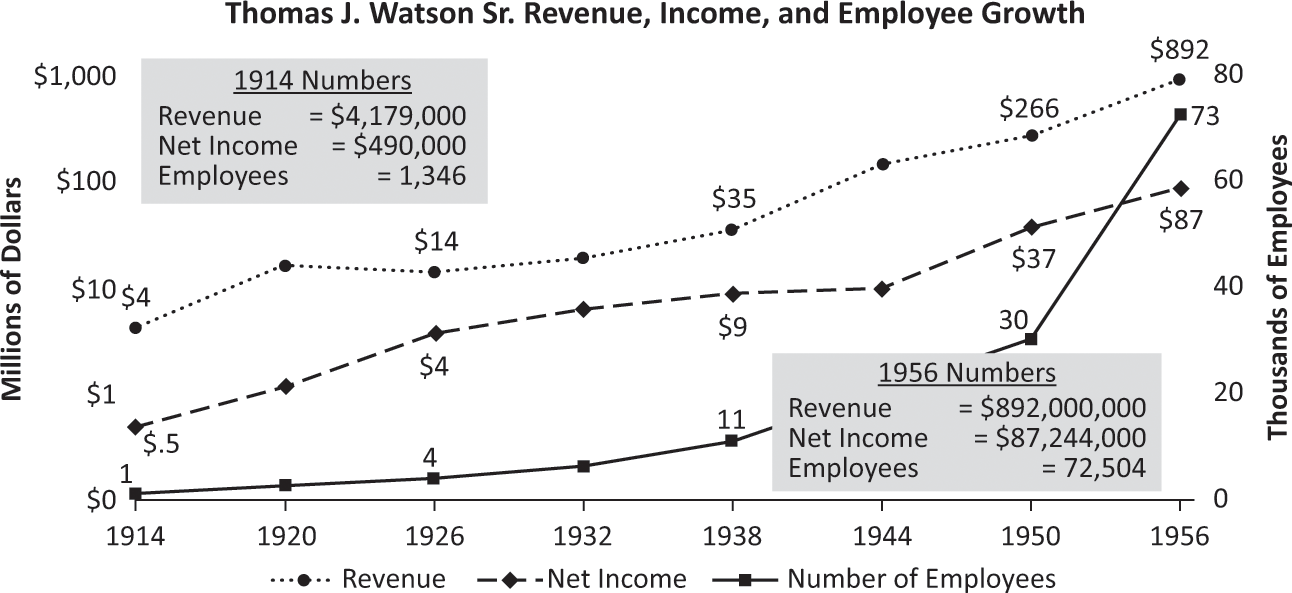

When IBM’s accountants closed the books on 1956, they reported the corporation had booked $892 million in revenue; the following year, the company jumped over the $1 billion mark in revenue, growing business by an additional $300 million. When Watson Sr. died, 51,000 employees in the United States and an additional 21,000 scattered throughout the world, their families, and customers paused to mark his passing. Think magazine, which still carried articles about IBM, devoted the entire Fall issue to his life. The whole company seemed in mourning. And to think that when Watson Sr. came to C-T-R in 1914, the company only had 1,346 employees and had generated $4 million in revenue and $1 million in profits. The year he died, IBM reported $87 million in profits (see figure 7.1).

A summary of IBM’s business performance and growth while led by Thomas J. Watson Sr. Courtesy of Peter E. Greulich, copyright © 2017 MBI Concepts Corporation.

It is routine in histories and memoirs of IBM to see 1956 as a transition date because of Watson’s death, but it was not a significant date in the daily affairs of IBM. IBM had already stepped into a new era of business coming from computers, different from the one the Old Man ran. Since the return of his two sons from the military, Watson Sr. had been slowly letting loose his reins of power. Kirk and Phillips had been running much of the day-to-day operations since the late 1940s, while Tom Jr. embraced computing as his ticket to success. In 1952, Watson Sr. made him president of the company, and while the two men disagreed over policies and decisions, the father gave in to his son, grudgingly if strategically appropriate at first but by the mid-1950s by necessity caused by old age and the growing evidence that Tom Jr. was up to the task of leading “his” company. It is why IBMers could pause to pay tribute to Watson Sr. and then keep growing. The year after Watson Sr. died, IBM hired another 11,000 employees and brought in $110 million in profits on revenue of $1.2 billion.19

ANOTHER ROUND OF ANTITRUST ACTIVITY

But Tom Jr. had to earn the right to lead the transition. Historians and IBM memoirists are in agreement that during the transition from father to son, the key switch unfolded as the two dealt with a new bout of antitrust litigation. It is a case that is quickly described by most historians before moving on to other topics.20 However, it cast a long shadow over IBM’s U.S. operations for years. New employees showing up for work in the United States in the late 1950s and 1960s went to Endicott for initial training about IBM, its role, and its products. Their welcome packet contained a map of Endicott, a directory of churches, a flyer about the IBM Country Club, and booklets about IBM’s Suggestion Program, its products, and Chamber of Commerce literature.21 But also included was the text of the “Final Judgment” of “Civil Action No. 73-344,” better known as United States of America v. International Business Machines Corporation, filed and entered on January 25, 1956. This 36-page booklet spelled out in legal language what came to be known as the IBM consent decree of 1956. In particular, salesmen in the United States were admonished to live by its terms, and a small army of IBM lawyers and “business practices” staff patrolled their activities. By the 1970s, new hires and those attending Sales School heard a lecture on its terms, delivered by an IBM lawyer.

H. Graham Morison, the U.S. assistant attorney general running the Anti-Trust Division in the early 1950s, was on a roll, successfully prosecuting cases against large corporations. Looking at IBM’s dominance in the punch card and tabulating markets, he considered Watson Sr. “a robber baron” who had been “getting away with it for years.”

Tom Jr. was president of the company when government lawyers came calling, and he took the lead in defending IBM. Events revealed IBM’s view of the market. On Monday morning, January 22, 1952, at 8:11 P.M., Charles E. McKittrick, an IBM manager in St. Louis, received a telegram from Western Union, signed by Tom Watson Jr., as did sales managers and executives all over the country: “Late this afternoon the Department of Justice announced to the press that it was commencing a civil suit against IBM charging monopoly. The investigation that resulted in this action started about 7 years ago. We have gone into the matter exhaustively and feel our position is unassailable. A letter containing details is being mailed to your office at once. This letter will give you information with which to answer detailed questions. Meanwhile we want you to know that the company’s position is strong.”22 Since the 1920s, senior management had quickly informed “the field” of unfolding major events in the belief that IBM’s employees and customers would discuss them. To maintain a unified voice, it was essential to create a narrative, a point of view, on an issue. The telegram demonstrated how IBM did this. The government’s press announcement was no surprise to Corporate.

The day before the promised letters (there were two separate ones) to the field had been completed, Tom Jr. instructed all IBM managers and district managers “to hold a meeting at the earliest possible time to read and discuss the enclosure with all personnel. Questions are to be encouraged and the fullest possible explanations given so that every IBM man and woman will understand the Company’s position.” When queried by customers, salesmen could “illustrate IBM’s competitive position” by reminding them of all the other vendors, machines, and methods that they and other customers used and that their “personal opinion is the major determining factor in the choice of the type of machine used on each application in each company,” not some monopolistic action by IBM. To the public, IBM declared it was not a monopoly, saying, “We deny the charge.” Watson Jr. wrote to his managers: “The complaint filed by the Department of Justice appears to be based on their idea that the punched card field is a separate field from that of other business machines designed to perform accounting and record keeping work, and that, since we have a major portion of the punched card business, we are, therefore, a monopoly. We know, of course, that punched card machines do not occupy a separate field in accounting and record keeping work, but rather that they constitute one of the many machine methods being used today by American business.” He ended with, “No one better understands just how competitive our market is than you men in the field.”23

Two single-spaced typed pages of statistics on market shares of IBM and its dozen largest rivals were attached to these communications to demonstrate that the market consisted of $932 million in sales, of which $215 million (23.1 percent) was IBM’s, and that its definition was understated, because revenues for four major competitors (Elliott, Friden, Powers, and Victor) were unpublished. All 16 listed companies sold products used for “personnel records, payroll, sales accounting, billing, accounts receivable, accounts payable, cost accounting, inventory and material, property records, financial control, corporate records, and operating records.”24

Both Watsons called on Morison in 1952 to explain that IBM did not dominate the office appliance industry and that the tabulating portion of that market was small. The assistant attorney general did not buy the argument. His problems with IBM arose from their forcing customers to use only IBM-made cards so other firms could not enter that market; that IBM killed off competition by buying patents; that by only leasing machines rather than selling them IBM prevented the emergence of a secondary market in used IBM machines and parts; and that this practice made it impossible for others to compete with IBM to provide service for its machines. Morison said he could have filed a criminal case, but he opted for a civil suit.25

Watson Sr. must have had a rush of bad memories of the criminal case at NCR and the civil suit against IBM in the 1930s. Now here was a third one, just as he was ending his career at IBM. There was truth in everything Morison said. IBM had collected patents, hired rivals, invested in patentable R&D, and maintained leasing and card sale practices, despite the antitrust actions of the 1930s. IBM had always been aggressive, combative, and competitive in dealing with rivals. Now again the U.S. government wanted to punish Watson for doing what he believed was such an American thing—running a successful, growing business—within the cultural norms of the day.

His ethics challenged, Watson Sr. refused to give in to a consent decree. He wanted to fight Morison. Tom Jr. saw IBM’s future in areas that were not part of the case, specifically its growing computer business. The case seemed a leftover from before World War II. IBM’s legal counsel said the company could be sued because it had monopolistic power under the Sherman Antitrust Act. Tom Jr. wanted to settle and get past it, but his father stubbornly resisted. They debated, argued, and Tom Jr. even shouted at him over it. The case dragged on with endless rounds of meetings within IBM and with the Justice Department. Tom Jr. was president of IBM but could not put an end to it without his father’s permission, as Tom Sr. was the chairman of the board. Tom Jr. believed IBM would have lost the case because it had sharply dominated its chosen market.

Then, in late 1955, it all came to a head. Tom Jr. was just leaving his office at 590 Madison Avenue and ran into his father in the hallway. When his father asked where he was off to, Tom Jr. said he was going to see the judge. His father exploded, saying he was wrong to do that, and when Tom Jr. asked if his father wanted him not to go to the meeting, Watson Sr. said go but don’t make any decisions. Tom went off to see the judge, and while he was at that meeting, an IBM secretary slipped into the room and handed him a note from his father:

100%

Confidence

Appreciation

Admiration

Love

Dad

Everyone who has reported on the event drew the same conclusion, confirmed by Tom Jr. in his own memoirs, that his father at that moment had truly turned over IBM to his son and that Tom Jr. realized it while in the judge’s conference room.

Tom Jr. moved quickly, and on January 25, 1956, he signed a consent decree with the U.S. Department of Justice. IBM agreed to offer machines for purchase or lease at comparable total cost; it would allow others to sell punch cards to IBM’s customers; and it would license some of its patents, among other terms. The actual settlement was pretty benign, largely about shrinking markets as IBM moved into tape-based computer sales. Watson Sr. ordered employees to adhere “100%” to the terms of the agreement, which is why a new employee showing up at Endicott received the 1956 consent decree to study.26

TOM JR. TAKES FULL CHARGE OF IBM

Some consequences of the consent decree were less visible: Watson Sr. turned over daily operations to his son, spent more time helping Arthur Watson with business in Europe, and began to address some of his own ailments. He was 82 years old, frail, and losing weight. On May 8, he politely and with dignity asked Tom Jr. to assume the role of chief executive in addition to his role as president. Watson Sr. retained the title of chairman, and his aging sidekick George Phillips would serve as figurehead vice chairman until the latter’s impending retirement. Tom Jr. had proven to his father that he was ready to take over leadership of the company. It was an ideal transition and widely expected by IBMers, customers, and observers. It was clear to the elder Watson that a different IBM was emerging, with a new generation of competent executives and IBMers eager to get into the computer business. His work was done. On June 17, his heart began to fail and his family gathered around him at Roosevelt Hospital in New York. On June 19, his heart stopped, he took his last breath, and gently passed into history. The court case had been his last battle.

As Tom Jr. expanded his influence, he imposed his style of management, best seen by his first reorganization. His managerial problem was straightforward to describe but difficult to fix: IBM was getting too big for one or a few people to manage. Multiple computer products, each with their own R&D issues, exemplified one aspect of the problem. The tabulating machine business generated the lion’s share of IBM’s revenues. While that market experienced less change, the sales force defended it in the face of what Tom Jr. saw as the future: computers. The move into computing promised larger revenues, but also increased costs for R&D, infrastructure, and marketing. In the 1950s, IBM faced a growing list of well-financed, creative competitors for computers, a good half dozen in the United States alone. Outside the United States, IBM had to expand into new cities and industries, all of them expensive and requiring localized attention and more hiring. That expansion called for increased coordination. As the computer market heated up, IBM and others introduced new products. IBMers had to do something with older computers and tabulating equipment, deciding to sell them into less developed, less competitive markets, such as Asia. All these various activities were sufficiently different from one another, each with its own organizational and staffing requirements, expense structure, and profits, that Corporate could not manage and coordinate them as it had in earlier times.

Tom Jr. had seen in the army how a large organization operated, while he also observed how companies bigger than IBM made decisions. His answer to the problem was to distribute decision making and responsibility for results. Here was a clear break from his father’s centralized administrative style. They had different styles of management, but fortunately for IBM, their styles matched the needs of their times: Watson Sr.’s authoritarian hand in shaping the original company, his son’s more collegial and inclusive style for a diverse business ecosystem. The Old Man did not tolerate objections. Tom Jr. welcomed them and indeed insisted on being exposed to differing opinions. However, both men expected absolute obedience in implementing a decision once it had been made.

Tom Jr.’s ability to successfully launch a process for reorganizing IBM’s assets and employees made him the fourth founder of IBM after Flint, Hollerith, and Watson Sr. When he was done, IBM was substantially larger than Watson Sr.’s company, and with the help of his brother, Arthur, had become a global behemoth. It had exited the tabulating business that had sustained it for a half century, making itself totally a computer vendor, led by a generation of executives and middle managers able to use Watson Sr.’s sales culture but also reflecting Tom Jr.’s style of management. In addition to the incremental changes Tom Jr. implemented in the first half of the 1950s was his all-important meeting held in Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1956.

In his memoirs, Tom Jr. argued that he feared not being able to run the huge business on his own, so he needed others to participate. He brought together 110 IBM executives to distribute power and responsibility. He succeeded, or to put it in his words, “In three days we transformed IBM so completely that almost nobody left that meeting with the same job he had when he arrived.”27 They came to the meeting after many changes at IBM that year: Tom Jr.’s promotion to chief executive officer, settlement of the antitrust suit, and the death of Watson Sr. It was the first gathering of senior executives in a meeting without the Old Man. They were now on their own. It was exciting and a bit unnerving. The only holdover present from Watson Sr.’s reign was George Phillips, who was due to retire later that year. Everyone else was new and from a generation after Watson Sr. At only 42 years old, Tom Jr. was typical.

So what did Tom Jr. do? He relied on preliminary planning by a Harvard MBA, Richard H. “Dick” Bullen (1919–2005). Bullen had entered IBM’s sales force in 1945 after serving in the U.S. Army and stayed at IBM for 27 years, retiring as a senior vice president. He was compatible with Tom Jr. In Tom Jr.’s words, “We took the product divisions that we’d already established, tightened them up so that each executive had clearly defined tasks, and then turned the units loose to operate with considerable flexibility. These were IBM’s arms and legs, so to speak.” At the top of the management pyramid, the group created a corporate management committee, an innovation that continued to operate under various names up to the present. This committee, initially with only about six members, oversaw plans and important decisions. The initial group included Tom Jr., his brother, Arthur, running World Trade, Williams, LaMotte, and Learson. Each assumed responsibility for a “piece of IBM,” with Tom Jr. roaming across the entire corporation.

The attendees at Williamsburg also created a corporate staff with specialists in finance, manufacturing, personnel, and communications (later marketing) that essentially characterized Corporate staffs over the next half century. Their job was to coordinate so that one did not have multiple divisions unwittingly duplicating activities or simultaneously bidding for business. It was a noble attempt to break up political competition but worked only partially, because divisions still competed against each other for influence and resources for decades. The work done in Williamsburg paralleled what many other large corporations had already done in creating a “line-and-staff structure,” which Tom Jr. acknowledged was “modeled on military organizations.” His description of the approach could just as easily be read as a history of IBM’s managerial culture for decades to come:

Line managers are like field commanders—their duties are to hit production targets, beat sales quotas, and capture market share. Meanwhile the staff is equivalent of generals’ aides—they give advice to their superiors, transmit policy from headquarters to the organization, handle the intricacies of planning and coordination, and check to make sure that the divisions attack the right objectives.28

Most participants at the meeting grew up in sales and knew how to get things done. The challenge was to figure out what to get done. They had to become more strategic, not just good operationally. Tom Jr. told the assembled executives, “Now we must learn to call on staff and rely on their ability to think out answers to many of our complex problems.”29 That style of management remained for the next 60 years.

Watson Sr.’s “yes men” were gone. Tom Jr. did not bring in outsiders except when specific technical skills were needed, as in law and science. The company could always hire consultants to advise it on specific issues as needed. At the meeting, new assignments were handed out. Al Williams assumed the role of chief of staff, ensuring that a highly admired field executive would attract respect for these staff from the product and sales divisions. According to Tom Jr., “The great strength of the Williamsburg plan was that it provided our executives with the clearest possible goals. Each operating man was judged strictly on his unit’s results.”30 All major decisions were subjected to financial analysis so their impact on IBM could be understood. Others would look at the public relations component to make sure decisions enhanced IBM’s reputation. Still others would make sure manufacturing could turn in the highest levels of quality and productivity. Watson was thrilled with the results of the conference, saying, “There was no doubt that IBM had been totally transformed.”31 He soon published one of the first widely distributed organization charts in IBM’s history.

In the months that followed, Williams filled new staff positions, division presidents reorganized in a similar staff-and-line manner, and managers began writing strategy and operational papers. Thinking strategically and expressing themselves in writing became important components of a manager’s tool kit. It became increasingly impossible to sustain a career at IBM without being able to be thoughtful about the nature of its business. Employees had to be effective in performing the day-to-day job. In subsequent decades, one’s normal career path involved a back-and-forth rotation between line management (running something like a sales office or manufacturing operation) and staff, all the way to the top of the firm.32 Tom Jr. and his management team now had an organization in which decision making projected out and down into all divisions worldwide in a structured way. Divisions held the authority to execute with the help of corporate staff. Arthur remained head of World Trade, although he was now a member of the corporate management committee. He reported directly to his brother.

After the Williamsburg meeting, the United States remained the center of IBM’s market through the 1980s. It also proved to be the most competitive one. In 1956, there were 756 computers installed in the United States, representing a sharp rise from approximately 20 at the end of the 1940s. Computers in 1956 were commercial products, not one-of-a-kind devices. Commercial enterprises used most of the business-oriented smaller systems, scientists and engineers the bulk of the larger ones, and government agencies a combination of small, medium, and large computers. To build on the Williamsburg reorganization, in 1959 IBM implemented yet another restructuring, dividing the company into two parts, essentially aligning products and customers based on whether they spent more or less than $10,000 per month in rental fees. For smaller customers, the General Products Division (GPD) would develop and manufacture products. GPD took responsibility for the RAMAC and 650. A second division, the Data Systems Division (DSD), took over the 700s and other large systems.33 Each developed its own sales force.

The reorganization was not perfect, because sometimes a large customer might also want small computers and therefore receive the attention of two divisions competing for sales, but the new structure worked in creating a focus on different emerging markets. Other things did not go so smoothly. GDP gained responsibility for the 1410, whereas it really should have gone to DSD. Multiple operating systems began to proliferate when engineers did not anticipate the problems that would cause for the firm. Success led to more diversity, with eight solid-state computers in 1960 alone, from the 7070 at the high end to smaller systems such as the 1400s and 1410. Two years later, the 1440 came out, with disk storage, and in 1963, the 1460 was introduced, with faster printing and memory. Each system used different peripheral equipment, adding to the plethora of products.

In 1964, the year IBM introduced the System 360, the focus of chapter 8, 19,200 computers were installed in the United States. Big, boxy mainframes accounted for about 87 percent of all systems in 1964, the rest being smaller devices, many of them sold by vendors other than IBM. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the U.S. economy absorbed about 500 big systems a year. IBM’s market share for large mainframes hovered at 80 percent all through the period. The market was expanding so fast that IBM’s rivals also initially did well. These included RCA, NCR, Remington Rand, and Honeywell at the high end, CDC with its supercomputers, and Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) and SDS with small systems. Most were large enterprises that had ample financial resources to take on IBM.34

COMPUTERS COME TO WORLD TRADE

Outside the United States, IBM also had a rapidly developing market for its computers. The computer industry quickly became a global industry, although historians of IBM have focused more attention on events in the United States. That situation is changing, however. Martin Campbell-Kelly and Daniel D. Garcia-Swartz, in their history of the computer industry, covered international developments as thoroughly as those in the United States.35 In an earlier study I conducted on the worldwide diffusion of computers, it became obvious that earlier historians had underestimated the extent of computing in many countries but that IBM had not.36 Discussing IBM’s international computer sales as though they had begun in the 1960s, as had been the custom since the days of Robert Sobel’s useful account of IBM, is being displaced by a greater realization that all vendors were affected by international events, from embracing technical standards to conforming to local business practices across Western Europe, Japan, and Latin America in this crucial era of the 1950s through the early 1960s, when American companies expanded outside the U.S. market.37

Recall that after World War II Watson Sr. had to find homes for both his sons in IBM, admittedly a blatant act of nepotism reminiscent of similar practices by other firms, such as at the Ford Motor Company. He decided that he would groom Tom Jr. for the opportunity to run the company. As Tom Jr. moved up the corporate ladder, he demonstrated his ability to perform new responsibilities. Then there was Arthur to place. Watson Sr. solved the problem of Arthur’s career trajectory and also how to manage foreign business. Remember that in 1946 Europe had a destroyed economy, a third of its physical infrastructure needed rebuilding, and there were even people starving. Watson Sr.’s assorted collections of prewar companies needed to be restarted, reorganized, and rationalized into a coherent form. The major markets for tabulating equipment, and soon for computers, were the same as before—Great Britain, France, West Germany, and Japan—with a second tier of smaller but attractive economies, such as the Netherlands, all the Nordic countries outside the Soviet bloc, Italy, and Spain. A number of countries in Latin America also presented opportunities, primarily Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, and Peru, but also a second, smaller group, which included Cuba, Venezuela, and Uruguay, among others. In a third category, smaller than the first two, were colonial outposts of the European states of old. These were often in Africa and Asia, where the customers were local extensions of European organizations.

In 1949, Watson Sr. created a subsidiary called IBM World Trade Corporation (WTC) and put his son Arthur in charge of it. Its results were reported in the company’s annual report as a separate line item. Country-level companies were established as wholly owned components of the WTC. That is why, for example, some countries published annual reports of their own, such as France, while World Trade reported its financials, too. Corporate in New York eliminated various odd naming conventions. Now each national company was called IBM and the name of the country, such as IBM Spain or IBM Japan, both in English and in their local language.

While IBM’s global performance is discussed in more detail in chapter 11, in the 1950s demand for IBM’s products was so great that World Trade grew faster than the domestic company. It experienced less competition and growing demand for IBM’s products, although the number of computers installed lagged that of the United States. However, rivals were similar: office appliance firms (such as British Tabulating Machines), electrical supply firms (such as Ferranti and English Electric in the British market, Siemens and SEI in West Germany), and start-up computer vendors (such as Leo Computers in Britain, Zuse in West Germany, and SEA in France). IBM was constrained by the U.S. government and the Soviets regarding how it could operate behind the Iron Curtain, which enveloped Europe from the eastern end of Berlin to the Chinese border. China was engaged in a civil war that resulted in the Communists taking control in 1949; they, too, blocked U.S. businesses. IBM World Trade operated similarly to IBM’s domestic business: it built factories and a sales force, and it imposed consistent managerial practices worldwide. Overall, it was not uncommon for Europeans to double the number of installed computers from all sources year over year, while the Americans, with their larger base, grew at a slower pace. In 1955, Europe had 27 computers, whereas the United States had 240; in 1960, Europe had 1,000 systems, the United States 5,400; and in 1964, Europe had 6,000, the United States 19,300.38

By the late 1960s in most countries, between 60 percent and 80 percent of all systems came from IBM World Trade, despite efforts by local governments to support indigenous suppliers.39 Already in the 1950s, worldwide, IBM had more computing capabilities than any other company, including European challengers. To quote Campbell-Kelly and Garcia-Swartz, “IBM was more daring in its attempt to grapple with the challenge posed by digital computers,” both in the United States and in Europe. “IBM was always one step ahead relative to its European peers, both in incorporating electronics into traditional data processing equipment and in exploring the possibilities of digital computers,” they added.40 That situation remained through the 1980s. While World Trade experienced less competition, European businesses and agencies proved slower to embrace computing than their American counterparts had been.

WHY DID IBM SUCCEED IN THE COMPUTER BUSINESS?

We need to ask this same question for each period, because the answer is key to understanding how IBM became iconic. Historians are increasingly reaching a consensus on the answer for the 1950s through the 1970s, centering on the combination of effective sales, excellent services, training of IBMers and customers, growing knowledge about electronics, and preexisting customers being well known to IBM. Jeffrey Yost argued that the firm’s ability to acquire necessary scientific and technological expertise in the construction of computers proved crucial.41 Others contended that IBM mimicked its competitors, citing its late arrival into the market. But in time, the tables turned, as rivals mimicked IBM’s approach, particularly in the 1960s. Tom Watson Jr. attributed the transition’s success to his superior workforce’s selling approach. Anticipated end results always remained uncertain, as the technologies proved risky and unstable, evolving rapidly in form and function, while being expensive to develop and use. It was urgent to bring these technologies to market, as over a dozen rivals in the United States alone were engaged in doing the same by the early 1960s. In four books, Emerson Pugh, who spent his IBM years in R&D, described the risks while calling out the uncertainties and difficulties of developing and selling this new class of products.42 Historian Alfred D. Chandler Jr. and IBM memoirists made the point of the importance of coordinated action, even though uncertainty hovered over IBM’s initial forays into the computer market.43 That is why the initiative at Williamsburg proved so important. It reinforced specialization in those skills and know-how essential to the emerging markets in combination with organized collaboration and control.

When analyzing the early history of the computer industry, Campbell-Kelly and Garcia-Swartz spoke of IBM’s capabilities as “phenomenal” while acknowledging that IBM did not always have the best, most advanced computers. This admission was made also by Tom Jr.—“It offered the best systems—the best bundles of processors, peripherals, software, and services.” Many rivals had good computers but poor-quality peripherals (such as tape drives or printers), or software but not hardware, and so forth. The key was bundling, which is why I highlight the word bundles, one for each mainframe computer, a concept Watson Sr. and even Hollerith before him had used in putting together (configuring) systems (groups of machines working together). IBM’s ability to put together the whole package—product, training, sales, and services—proved especially attractive to customers acquiring computers for the first time, which for them involved “dealing with the uncertainty of adopting an unproven technology.”44

Another historian, Usselman, well versed in the interaction between IBM’s strategy and how it organized itself, offered another view consistent with the bundles idea. He reminded us that the IBMers in Poughkeepsie pursued the high-end scientific computing needs so often funded by the federal government, while others in Endicott converted IBM’s traditional electromechanical products into all-electronic ones that, when combined with what was going on in Poughkeepsie, made it possible for IBM to produce data processing systems. But each remained sufficiently distinct to appeal to specific audiences. Government managers requested proposals to meet specific computing needs. IBM’s engineers and salesmen responded best when asked to devise a solution to a customer’s problems—the way they sold tabulators. They fared poorly when bidding based on price. The government’s procurement process created a competitive market with opportunities to compete that included GE, RCA, and others. To respond to a problem-oriented bid, a successful bidder would need to coordinate solid sales execution, maintenance, and both software and hardware. That is how IBM naturally operated. Each win introduced IBM to new customers, as happened with SAGE. That project alone catapulted IBM squarely into the middle of military computing, which grew massively as the Cold War unfolded over the next three decades.45

Usselman also offered an interesting twist to the story: the notion that IBM was humble. Hubris among technologists working on new computing machines was rife, but not at IBM. IBMers did not claim a monopoly on computing know-how. IBM bought components, just as in the tabulator days. Employees listened to customers about how to resolve an operational or design problem, as happened with the Social Security Administration in the 1930s and with Northrop in the 1940s, the first with punch cards, the second with early IBM computers. So IBM occupied a middle ground of sorts, becoming a gearbox, an information center for its customers. IBM did not lean into a customer with tales of fancy engineering, unlike ERA and Univac salesmen, but instead led with business considerations. It all worked.

By the mid-1950s, IBM dominated the four existing market segments: large commercial systems (such as those served by Univac); large scientific and engineering installations; systems that did real-time processing, such as SAGE; and small companies just getting into data processing. For these four segments, IBMers led with the 700s, SAGE, and the 650, and later the 1401s. That collection of machines and markets gave IBM’s senior management insights that made development of the System 360 possible, which is why Tom Watson Jr. and his executives could take remarkably bold steps in the 1960s that further transformed the company. Watson understood what was happening and had a far greater tolerance for the turbulence and ambiguity inevitable with emerging technologies and markets. That is why decentralizing authority made it possible to leverage—to coordinate—much insight and knowledge within the firm.

Then there was “the field,” the matrix of sales offices set up all over the world, staffed with well-trained salesman who went out every day to do IBM’s work. Recall that since the 1920s IBM had tracked sales calls made on customers, which is why, in 1952, Tom Watson Jr. could tell his sales management that “for every new account we sell, our salesmen make 135 prospect calls” and that “of the 100,000 larger business establishments in the United States, 94,000 accomplish all their accounting and record keeping work without IBM accounting machines. Fewer than 6,000 are IBM punched card customers,” evidence of the company’s early and long-lasting large-account focus. Tom Jr. added that of the largest 7,000 enterprises and government organizations in the United States, “only 7 percent of the total accounting cost is spent for IBM machines and operators.” Over half also used other vendors’ equipment, leaving management to conclude that their market was competitive in all industries. Watson Jr. stated, “Our selling efforts in the past have been directed toward fixing the buyer’s opinion in favor of our products. We intend to continue those efforts. That is the American way of doing business.”46

IBM’s momentum in the early 1950s may also be attributable to Watson Jr. becoming more confident in his abilities, although a reading of his memoirs suggests that ambiguity and complexity made him nervous. Like his father before him, he was being recognized as a success. In this company’s case, nepotism helped, too. A small, telling piece of publicity must have pleased him enormously, because his father was still alive and certainly would have seen it. The March 28, 1955, issue of Time magazine carried a picture of the younger Tom Watson on its cover. He looked distinguished with his greying hair, serious, and confident. The lengthy, laudatory article placed IBM at the center of the new computer era. In a cover note accompanying a reprint of the article sent to IBMers, Watson Jr., the new president, commented, “My father and I realize that it is only through the efforts of every employee of the IBM Company that the type of reputation reflected in the TIME article can be brought about.”47

An opinion survey conducted in the U.S. field organization in 1960 offered evidence that the good feelings extended out from Corporate. Ninety-five percent of the 16,000 employees who completed the survey reported that they were enthusiastic about working for IBM. Ninety-seven percent were bullish about the company’s future prospects. They liked the type of work they did (92 percent positive), the kinds of colleagues they worked with (93 percent positive), the company’s benefits, and IBM’s reputation. They reported that job security and opportunity for advancement were excellent. Of course, they groused about not being paid enough, that one’s immediate managers did not communicate sufficiently, the existence of some favoritism, and growing work pressures. These were the kinds of pluses and minuses employees reported in other surveys between the 1950s and 1980s. Write-in comments, coming from salespeople working with customers, provided additional evidence of IBM’s growing influence:

“There is a definite amount of prestige in being able to say you work for IBM.”

“The name IBM is … respected and admired throughout the business world.”

“Impeccable reputation and outstanding ethics in business matters.”

“Pride in being with a company that is a leader in its field and enjoys the respect of the majority of people I come into contact with.”

“The company name is well known and opens doors.”48

The last point would have pleased Watson Sr. the most, because he had worked for decades on establishing IBM’s status precisely to “open doors” to IBM business. IBM in the late 1950s and early 1960s had entered its Golden Age.

KEEPING SCORE ON THE 1950s AND EARLY 1960s

A few numbers help to describe how the company changed. In 1946, IBM generated $116 million in revenue and from that $10 million in net earnings (profits). Volumes increased all through the 1950s and early 1960s. In 1964, the last year before IBM began shipping System 360s to customers, it generated $3.2 billion in revenue worldwide, of which $2.2 billion came from leasing computers, and $431 million in net earnings. Roughly a third of all revenue came from outside the United States, from IBM World Trade.49

IBM enjoyed positive blips in its revenue, too. For example, it began earning money from the SAGE project in 1952, when it received $1 million, a sum that crept up slowly until 1955, when it drew in $47 million. Revenue then climbed each year to $122 million in 1957, slipped to $100 million the following year, then began to decline as installations were completed, but was still $100 million in 1958 and another $97 million in 1959. That last year, 8,000 IBMers worked on the project. The company kept drawing revenue from SAGE through 1964, for a grand total of over a half billion dollars between 1952 and 1964.50

Other U.S. military contracts brought in additional revenue north of $700 million. Commercial computers in IBM USA began contributing to the revenue stream in the early 1950s, making the double-digit jump in 1956 to $49 million from the prior year’s $12 million. In 1957, commercial computer revenues in the United States tripled to $124 million and then kept growing. In 1963, IBM generated just over $1 billion in revenue from computer equipment and supplies in the United States and increased that number the following year by over $250 million, for a grand total of $1.3 billion.51 None of these revenues included the substantial contributions made by World Trade, discussed later.

Another way to look at IBM is by how many employees it had. In 1946, a total of 22,591 people worked at IBM, of which 16,556 lived in the United States. As with revenue, this population increased explosively over the period in the United States and worldwide. By the end of 1964, 149,834 people worked at IBM, of which 96,532 resided in the United States; sales expanded 15-fold and profits even faster, nearly twice that rate. But look more closely at the employees, who increased not only in number but also in type, with more engineers, college graduates, and staff in Europe, Latin America, and Asia. The numbers hide the fact that hiring was even greater than one might suspect as older IBMers retired, to be replaced with new people. Using statistics of year-end numbers of employees (called “headcount” in IBM language), the population increased sevenfold.52

While Watson Sr. turned in impressive growth numbers for revenue and number of employees, his two sons combined did a far better job in growing the business while simultaneously shifting from one technology base, electromechanical tabulators, to another, digital computers—all while continuing to increase business and profitability. The leadership for making that happen came largely from Watson Jr. and a new generation of executives and middle managers, most of whom were only in their 30s and 40s and ranging from less than 10 years to over 20 years at IBM. But their success came at a frightful price, the possibility of IBM crashing to death over their attempt to sustain its growth and solve myriad technical problems that many different types of computers imposed on IBM, its customers, and the computer industry as a whole. Their success also brought on the longest antitrust suit in U.S. history. How they began dealing with all these problems is the subject to which we turn next. It is the story of the System 360.