CHAPTER 4

SERPENT OF THE NORTH

The Overlook Mountain/Draco Correlation

The following paper was presented at the Midwestern Epigraphic Society 2010 Conference in Columbus, Ohio.

The stone constructions discussed in this chapter represent the discovery of a petroform; that is, a purposeful arrangement in rock or stone that may be geometric, animal, or human in shape. Covering an area of several acres on a southeastern-facing slope of Overlook Mountain in Woodstock, New York, a grouping of very large, carefully constructed lithic formations, when connected together and taken as a whole, appear to create a serpent or snake figure or effigy. The large stone constructions, consisting of six very large stone cairns along with two snake effigies or serpent walls, are surrounded by a few dozen much smaller stone cairns arranged in clusters and rows. Native American seasonal habitation sites have been documented nearby dating to 4000 BCE, and the site in recent years was visited by a Native American tribal preservation officer who, along with many other individuals who have visited the site, felt great awe, wonder, and deep respect for the ancient stone symbols present at the site. If the petroform is confirmed as authentic and constructed in antiquity, it can be inferred that the site was at one time (and still should be) considered sacred. Additionally, because of the close correlation between the two representations, it is proposed that the snake symbol petroform created by the large lithic structure on Overlook Mountain may represent the star constellation Draco (the Dragon).

HISTORY AND DESCRIPTION OF THE SITE

Overlook Mountain has long struck an iconic image, looming above the Hudson River valley, acting as a sentry to the easternmost woodland slopes of the Catskill Mountains in upstate New York. Drawn to those slopes for thousands of years, humans have worked and roamed there as prehistoric hunter-gatherers, early agrarians, colonial lumber cutters and hide tanners, early American glass blowers and quarrymen, and twentieth-century utopians, hikers, and hunters. With such a long and varied past, it is safe to say that Overlook Mountain can be recognized as a serial use area, an area used by many different groups of people for many different purposes and reasons for thousands of years.

Beyond that, Overlook Mountain has inspired and enlightened people and invoked feelings from the practical to the artistic and spiritual. The mountain has been the source and subject of countless paintings, drawings, illustrations, meditations, poems, and books, all seeking in some way to capture, experience, and ultimately document the essence and nature of the tangible as well as intangible aspects the mountain possesses.

There is little doubt that an aspect of paramount importance to the early indigenous dwellers of Overlook Mountain and the lands surrounding it, whose connection to the natural world was both intimate and profound compared to this day and age, would have been the relationship and connection between the mountain and the sky.

Fig. 4.1. Overlook Mountain in Woodstock, New York

Fig. 4.2. Historic marker documenting the Native American presence on Overlook Mountain (a); historic marker documenting bluestone quarrying activity on Overlook Mountain (b)

My interest in the history of Overlook Mountain began in 2004, when a cell phone tower was proposed for the California Quarry, a historic bluestone quarry on the lower slopes of the mountain that was operated up to the 1890s. During that period, the California Quarry, along with other smaller, surrounding quarries, contributed greatly to early American industry and commerce in the region. While researching the quarry property, I was introduced to the many stone mounds that were present on the 196-acre quarry property and nearby adjacent parcels. Early property deeds for the area show “ancient stone monuments” present from the first land grants, patents, and subdivisions recorded. These included the Hardenberg Patent, a large land grant from King George, and subsequent purchases and land divisions associated with the Robert Livingston family.

In all, nearly five dozen cairns have been identified on the southeastern slope of Overlook Mountain between an elevation of 1,100 and 1,500 feet. Most of the cairns are well formed and show deliberate construction techniques and practices, such as dry stacking and the use of retaining walls. In some cases it appears that quartzite and hematite “donation” stones, which are not structural in nature, were left on the piles.

The construction of the cell phone tower caused the destruction of five of the nearly sixty stone cairns present in the vicinity. In 2006, as part of the tower application review process, Sherry White, tribal preservation officer of the Stockbridge-Munsee Community Band of Mohican Indians, visited the cairns and expressed the belief that the larger of the structures could be memorial or “burial” cairns. Having toured the entire site, she believed that the Overlook Mountain cairn complex can likely be seen as a “sacred precinct” where memorial or burial cairns were constructed locally, over many successive generations, and perhaps as part of a much wider spread spiritual, ritualistic, ceremonial practice and belief. Due to the presence of cultural resources of historical (and perhaps prehistoric) significance at the site, a National Register of Historic Places application for the California Quarry property was prepared and submitted and is currently in review and pending with the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation.

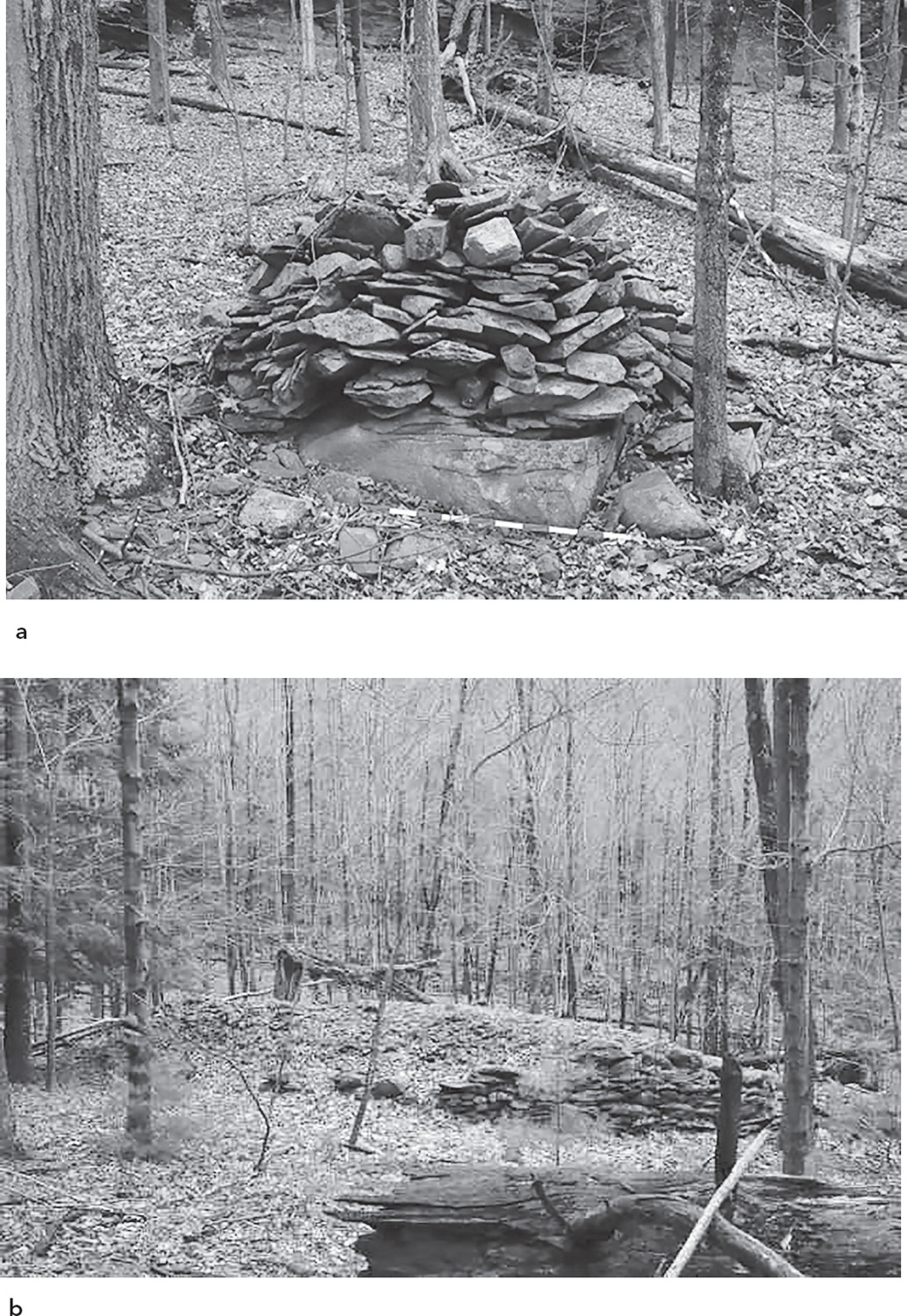

Fig. 4.3. Overlook Mountain cairn (a); Overlook Mountain “great cairn” (b)

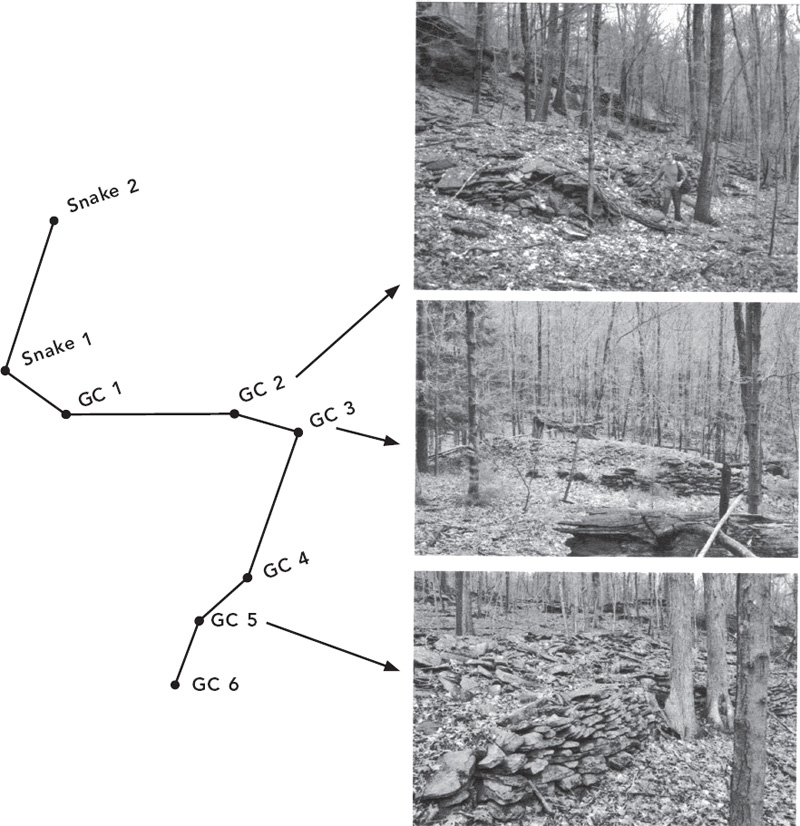

In 2008, NEARA members visited the site along with researchers from the New York State Museum in Albany. Susan Winchell-Sweeney, the museum’s geographic information systems specialist, conducted a GPS site survey documenting the quantity and location of the remaining stone constructions. In all, six very large cairns (up to one hundred feet in length), forty-six small cairns (up to ten feet in length), two snake effigies or serpent walls (ninety feet in length), and two springs were identified and their size and location data recorded.

After receiving the site data image (see figure 4.4) from Winchell-Sweeney in late 2008, I initially made little of the distribution, concentration, or configuration of the several dozen plotted points. There did seem to be deliberate groupings and clusters of the smaller cairns, while the “great” cairns appeared to be spread about more randomly. But nothing really jumped out at me. It wasn’t until about a year later (late 2009) that I revisited the data image with the intention of “connecting the dots.”

Fig. 4.4. GPS site survey data on the stone constructions at the Bluestone Quarry gathered by Susan Winchell-Sweeney of the New York State Museum

Fig. 4.5. Image showing the tracing of the eight large lithic constructions (a); connecting the dots to create a petroform (b)

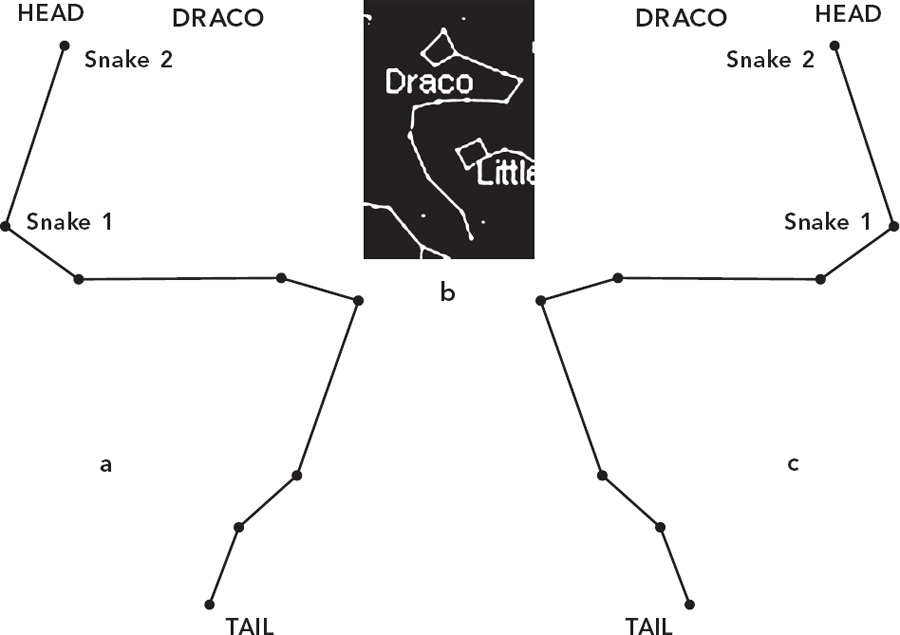

Dave Holden, who had first introduced me to the cairns, suggested that perhaps connecting the points could reveal a pattern, which he believed on a hunch could depict the Pleiades star cluster. Somewhat skeptical, I decided to conduct the exercise of tracing the dots onto a piece of paper and comparing them to a star chart of the northern constellations. Winchell-Sweeney’s data revealed there were eight large stone constructions seemingly randomly scattered about the mountainside site, six great cairns and two snake effigy walls, each a separate construction from fifty to one hundred feet in length. I decided to start by tracing the point of those eight locations on a piece of paper. I then connected the dots with straight lines in the only obvious and logical manner possible.

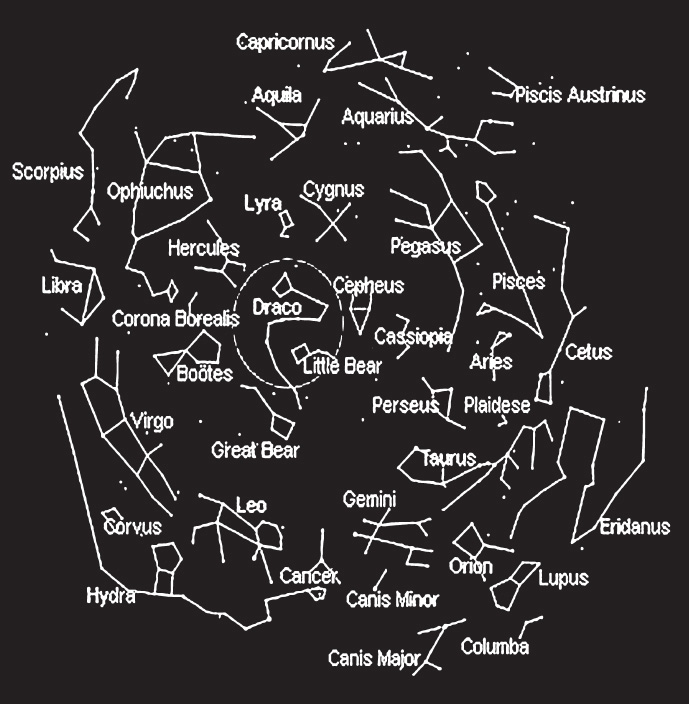

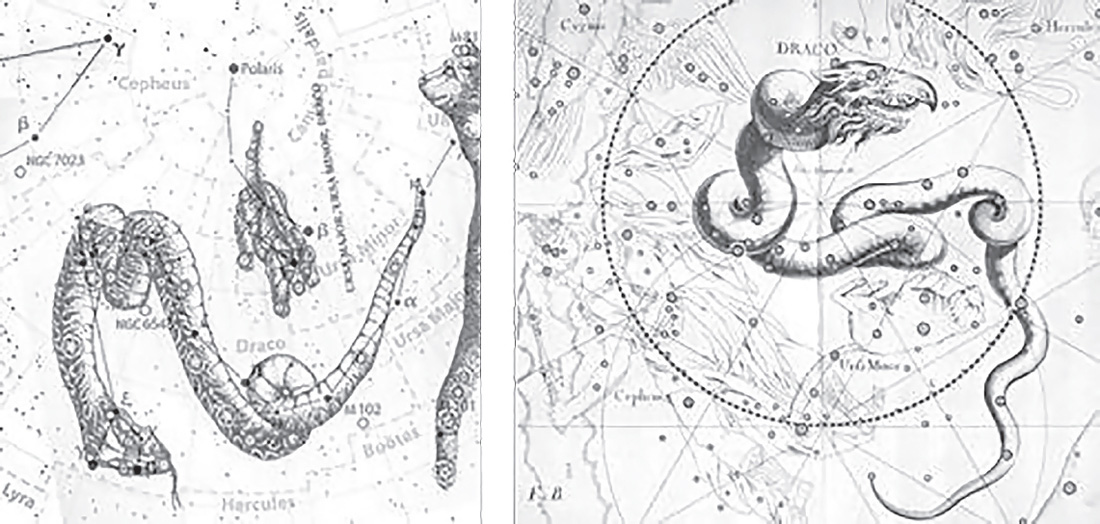

By comparing the tracing to the constellations, we see only one match that comes close. The constellation Draco, known as the serpent or snake constellation, is a close match in shape, configuration, and layout to the position of the stone mound constructions laid out on the ground. In fact, by mirroring the image of the cairn configuration, we see what appears to be an image of the constellation Draco reflected from the sky.

It should be pointed out that the eight points used to create the snake figure were not cherry picked but were distinguished from the rest of the cairns by size and the fact that the large constructions (fifty to one hundred feet in size) appear to be randomly placed, as opposed to the smaller cairns (six to ten feet in size), which appear in organized rows and clusters. Sorting artifacts by features such as size and relative position, I believe, is a standard method of classification and in this case provides the basis for determining the stone mounds that constitute the petroform on Overlook Mountain.

Fig. 4.6. Star chart of northern constellations

Fig. 4.7. Plot of the petroform (a); Draco star constellation (b); mirrored plot of the petroform (c)

Fig. 4.8. The Overlook Mountain petroform (a); the constellation Draco (b)

COMPARATIVE AND DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS

Draco is the eighth largest constellation, occupying more than one thousand square degrees in the sky as it winds from the Pointer Stars of Ursa Minor nearly to Vega in Lyra. Yet it has no bright stars. Gamma-Draconis, or Eltanin, the brightest star of Draco, has a magnitude, or apparent brightness, of 2.2 and is one of three or four stars that typically represent the head of the serpent. It is famous for being the star observed by the eighteenth-century English astronomer James Bradley when he was trying to detect the star’s parallax and so calculate its distance from Earth. Since Eltanin is considered the brightest star in the constellation, it is most likely to be seen as the star representing the head of the serpent on the Overlook representation, which appears to be consistent between the constellation and the representation. The spacing and angle between the stars and the representation—while close—are not an exact match, and the angle between Altais and Eltanin would also suggest that Eltanin is the single “head” star in the Overlook Draco representation, as opposed to Rastaban.

The total number of stars that represent the constellation Draco can vary from nine to fourteen, depending on the culture on which the representation is based. The constellation Draco has seven stars that are less than ten parsecs (thirty-two light years) from the sun, three stars brighter than 3.00 magnitude, and six that are currently known to have planets. The total number of stars represented in the Overlook depiction is eight.

Fig. 4.9. The eight brightest stars in the constellation Draco, listed from tail to head by their apparent magnitude, and the great cairns and their respective sizes

I thought it might be interesting to compare the magnitude of the stars that compose Draco to the size of the cairns on the ground to determine if there are any correlations between size and brightness. The table in figure 4.9 lists the stars in Draco by magnitude and the corresponding great cairns and their respective sizes.

A description of the individual component constructions that constitute the Overlook Mountain petroform follows, beginning with the two serpent or snake effigy walls located at the highest elevation (1,420 feet) of the eight locations involved. The easternmost of these two walls would serve as the head of the larger, component serpent (Draco?) petroform. And the two slightly curving stone walls, each approximately ninety feet long, each end at a large glacial erratic, which serve as heads to both individual effigy forms. It would appear the area around where the figure’s mouth would be located on the glacial erratics has been worked to accentuate the appearance of the mouth. The two wall serpents, whose tails point toward one another, are located approximately one hundred yards apart and are visible to and from each other when foliage is lacking, if one knows where to look. In fact, it was determined during a recent winter site visit that each of the large constructions, both serpents and great cairns, is visible from the next nearest petroform component. The six great cairns making up the remaining, lower portion of the petroform (between 1,401 and 1,300 feet in elevation) range from approximately sixty to ninety feet in length and are elongated, oval, or crescent shaped. The three largest of the great cairns are curving or horn-shaped and employ the use of retaining walls on the downward slope to allow the high piling of the stones within, in some places to a height of twelve feet.

Fig. 4.10. Images showing three of the six great cairns that compose the configuration documented on Overlook Mountain

NATIVE STONE CONSTRUCTION

According to archaeologist Edward J. Lenik, “Serpentine images carved into non-portable rock surfaces and on portable artifacts were invested with ideological and cultural significance by American Indian people in the Northeast.” In his book, Picture Rocks: American Indian Rock Art in the Northeast Woodlands, Lenik further states, “Snakes or serpents are ancient symbols and appear in rock art sites across North America. They are considered to be creatures of great power and craftiness. Among Algonquian-speaking peoples they may have represented evil and darkness or the energy of life or regeneration, or served as vehicles of transition for the soul of the deceased to the spirit world” (Lenik 2002). Could the Overlook Mountain petroform function as a guardian of the pathway souls follow to the heavens? Lenik also associates the Algonquin mythical Thunderbird as a guardian of humans against the Great Serpent of the underworld. If the Thunderbird is seen as the symbol of the protection of life, could the Serpent represent protection of the pathway of the dead?

Accounts of Native American stone constructions associated with definite astronomical attributes are not unique. Research in Mavor and Dix’s Manitou: The Sacred Landscape of New England’s Native Civilization went a long way toward proving that the people of the Native culture of the Northeast built with stone and that many of these constructions were associated with astronomical alignments and observations. This should not be surprising, as examples of this apparently geographically diverse cultural practice are well documented throughout the Americas and in fact worldwide.

Many examples of stone serpent effigy mounds exist and have been documented. An apparent stone serpent effigy (a wavy continuous line with snakelike configurations) can be found in Boyd County, Kentucky. L. G. Brisbin was the first to describe this serpent effigy (Brisbin 1976). S. L. Sanders’s 1991 article includes a nice drawing of the site and notes that it is “unique for its much larger size, well-defined serpent outline, strikingly bifurcated tail, and associated stone ring, which may represent an egg” (Sanders 1991). This effigy is said to have a solar alignment in the configuration of the head and tail. Brisbin notes also that the sandstone forming the serpent was quarried locally and that “in the head and coil portion, the stones are regularly piled to a height of 12 feet, but in the area of the body, they are stacked about 4 feet high and 5 feet wide until they thin out in the tail” (Brisbin 1976). Sanders gives a little more up-to-date information on the site. It is owned by Ashland Oil, Inc. The company has established a ninety-meter buffer between the mound and a nontoxic landfill, which serves an Ashland Oil refinery. The head of the serpent has been damaged both by pits excavated into the rock by unknown individuals and by the construction of a radio tower access road.

In another example, in a report on a preliminary investigation at the Skeleton Mountain site, 1CA157, Calhoun County, Alabama, by the Jacksonville State University Archaeological Resource Laboratory, begun in 2007, Harry O. Holstein states, “Native Americans are the likely candidates for the effigy construction,” and further, “One of the strongest reasons for believing the Skeleton Mountain Snake Effigy Site, 1Ca157, and other stone structures are an integral part of the Native American belief system has recently been expressed in a resolution introduced by the United South and Eastern Tribes (USET) at the Impact Week Meeting held in February of 2007 in Arlington, Virginia” (Holstein 2009).

Referring to similar stone structures in Tennessee, Holstein says, “The walls have been radiocarbon dated from AD 230 to AD 430, during the Middle Woodland period.” Regarding structures in Georgia, he says, “The three dates from the soil within the stone matrix immediately above the original ground surface (Layer 2) ranged from AD 3 to AD 1075 while the soil directly underneath the stones was dated to AD 1101, suggesting the mound was constructed during the Late Woodland to early Mississippian time period” (Holstein 2009).

Further, we find that specific examples of Native American petroforms matching the constellations exist as well. In his paper “Star-beings and Stones: Origins and Legends,” researcher Herman Bender argues convincingly for a petroform in Wisconsin known as the Kolterman Petroform Effigy, consisting of stone “stickman” formations constructed on the ground that create human figures known as “star beings.” The effigy figures are said to be associated with the Native American Thunderbird tradition and to mirror on the ground the constellations Libra and Scorpio as they appear in the night sky (Bender 2004).

In the case of the Overlook Mountain petroform, the comparison to the star group known as Draco cannot help but be made. I have consulted with astronomer Kenneth C. Leonard, who published the article “Calendric Keystone (?) The Skidi Pawnee Chart of the Heavens: A New Interpretation” and have confirmed that the constellation Draco would be visible rising above the summit of Overlook Mountain directly to the north before it reached its zenith overhead during daylight hours. And further confirming the assertion, using Starry Night Pro computer modeling astronomy software demonstrates that Draco rose above the mountain on February 1, 2700 BCE (when Thuban was the Pole Star), just before sunrise. And the serpent constellation has continued to rise over Overlook Mountain throughout the night for thousands of years since, occupying a permanent position perpetually spinning around the fixed celestial North Pole (Leonard 1987).

This is significant because to early sky watchers living in the Hudson River valley, occupying lands stretching for miles to the south, east, and west, Overlook Mountain would have been the place to look toward to see the Serpent of the North rising, night after night, to fulfill its duties protecting and making “precession proof ” the heavens. By “precession proof,” I mean no matter where the celestial pole drifted over time (due to precession), the dutiful dragon would always appear wrapped around that point, diligently spinning about the celestial pole, marking its location for those watching. We must remember that no star ever marks the exact celestial pole, which is the point in space where the Earth’s axis points as it draws a slow circle in the heavens (24,000-plus years) due to the apparent wobble of precession. What we consider the North Star now, Polaris, is merely the star that most closely marks the exact, true celestial pole. This star changes over time due to precession. More on this and Thuban, the past Pole Star, in the section “Thuban, the Once and Future Pole Star”.

Besides the connection to the sky, the connection of this mountain to the serpent or snake is also undeniable, and I don’t see this as likely a coincidence since Overlook Mountain has the highest population of eastern rattlesnakes in New York State, according to the Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC). It is estimated, based on the wear marks on the bedrock at the den entrances, that some of the rattler habitats have existed for centuries, at least. I think this is significant given the reverence the snake was accorded by the indigenous people, and it helps complete the picture of the sacred nature of the mountain in the culture of the Native population.

SERPENT MOUND AND CAMBODIAN TEMPLE CONNECTION

Documented images of snakes and serpents are not uncommon in the northeastern woodlands and elsewhere, and at least one other significant Native American example is claimed to have a connection specifically with the constellation Draco. It is said the Serpent Mound of Ohio (which is not dissimilar to the Kentucky serpent effigy) also may have been designed in accord with the pattern of stars composing Draco. The star pattern fits with fair precision to the Serpent Mound. The fact that the body of Serpent Mound follows the pattern of Draco may support various theses. Anthropologist Frederic Ward Putnam’s 1865 refurbishment of the earthwork was correctly accomplished, and a comparison to the maps of William F. Romain or Robert V. Fletcher and Terry L. Cameron’s from the 1980s show how the margins of the serpent align with great accuracy to a large portion of Draco.

Some researchers date the Serpent Mound earthwork to around five thousand years ago, based on the position of the constellation Draco, through the backward motion of precession, to the time when the star Thuban, also known as Alpha Draconis, was the Pole Star. Alignment of the effigy to the Pole Star at that position also shows how true north may have been found. This was not known until 1987 because lodestone and modern compasses give incorrect readings at the site. Using GPS and GIS methods produced better accuracy.

Most scholars date the Serpent Mound to the Adena culture, which flourished from 1000 to 200 BCE. Though few details are known regarding the religious beliefs and rituals of the Adena, many believe that the Serpent Mound sat at the center of their religious rituals and may have even served as a pathway for practitioners to walk, chanting hymns and thanking their gods for the continued fertility of the land and praying for its continuance.

It has been documented that trading territories and routes of the Adena culture extended along the southeastern shores of the Great Lakes, as well as the Hudson, Ohio, and St. Lawrence Rivers. So it is likely some of the religious and ritualistic aspects of the Adena culture diffused to the tribes of those regions and vice versa.

Considering evidence for the possibility of even further diffusion, we must look at the temples of Cambodia and, in specific, the sacred jungle pyramid-temple complex of Angkor Wat. In the book Heaven’s Mirror: Quest for the Lost Civilization, author and researcher Graham Hancock and his wife, Santha Faiia, document dozens of correlations between sacred constructions on the landscape and patterns created by star groups in the sky and alignments with solar, lunar, and stellar events on the horizon. One remarkable discovery, made in 1996 by one of their researchers, John Grigsby, Ph.D., was that the layout of the sacred complex of Angkor Wat, composed of the fifteen principal constructions spread out across nearly four hundred square kilometers of dense jungle, connected to model the serpent or snake constellation Draco. Using star mapping software, it was discovered that the date when the position of the locations making up the “ground Draco” reflected exactly the position of the constellation overhead was around 10,500 BCE. As Grigsby commented, “If this is a fluke then it’s an amazing one” (Hancock and Faiia 1998).

Fig. 4.11. The constellation Draco (top); layout of the Angkor Wat temple complex in Cambodia (bottom), from Heaven’s Mirror (Hancock and Faiia 1998)

DRACO AND MYTHOLOGY

From antiquity, Draco (the dragon) has long been known as the serpent or snake constellation. For a period in human history, the star Thuban in Draco marked the north point in the sky, as Polaris does now. This is a significant fact (see here).

Ophiolatreia, the worship of the serpent, next to the adoration of the phallus, is one of the most remarkable and, at first sight, unaccountable forms of religion the world has ever known. Until the true source from where it sprang can be determined and understood, its nature will remain as mysterious as its universality. It is difficult to reconcile mankind’s worship of a creature that is generally found repulsive. Yet there is hardly a country of the ancient world where it cannot be traced, pervading every known system of mythology and leaving proofs of its existence and extent in the shape of monuments, temples, and earthworks of the most elaborate and curious character.

Babylon, Persia, India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), China, Japan, Burma, Java, Arabia, Syria, Asia Minor, Egypt, Ethiopia, Greece, Italy, Northern and Western Europe, Mexico, Peru, America—all yield abundant testimony to the same effect and point to the common origin of pagan systems wherever found. Whether the worship was the result of fear or respect is a question that naturally enough presents itself, and in seeking to answer it we’re confronted with the fact that in some places, such as Egypt, the symbol was that of a good deity, while in India, Scandinavia, and Mexico, it was that of an evil one, a paradox that no doubt speaks to the struggle between good and evil in humans and a duality pervasive in their nature and the nature of the universe.

Fig. 4.12. Draco in mythology is most commonly depicted as a coiled snake.

Snakes and other similar creatures often played a role in creation myths. In these stories, the gods would often battle such creatures for control of the Earth. When defeated, the serpents were flung up into the skies. To the Babylonians, Draco was Tiamat, a dragon killed by the sun god in the creation of the world. To the Greeks, Draco guarded the Golden Apples of the Sun in a magical garden.

In the belief systems of many early cultures, the serpent and the sun were strongly connected. Native American oral tradition relates how at one time humans worshipped reptiles but were later compelled to recognize the sun, moon, and other heavenly bodies as the only objects of veneration. It’s said the old gods were secretly entombed in earthworks built to symbolize and represent the heavenly bodies.

Serpents are a common feature in the art of the late prehistoric period (900–1650 CE). As already mentioned, many American Indians of the eastern woodlands believed the Great Serpent was a powerful spirit of the underworld. Serpent mounds and snake effigies may be a representation of these beliefs and hold a connection to the cosmos through the constellation Draco.

In Reachable Stars: Patterns in the Ethnoastronomy of Eastern North America, George E. Lankford focuses on the ancient North Americans and the ways they identified, patterned, ordered, and used the stars to enhance their culture and illuminate their traditions. They knew the stars as regions that could be visited by human spirits, so the lights for them were not distant points of light but “reachable stars.” Guided by the night sky and its constellations, they created oral traditions or myths that contained their wisdom and that they used to pass on to succeeding generations their particular world-view. However, they did not all tell the same stories or see the same patterns. Lankford uses that fact—patterns of agreement and disagreement—to discover prehistoric relationships between Indian groups. In his book, Lankford devoted an entire chapter to “The Serpent in the Stars,” seen usually by the Natives as the Scorpio or Draco constellations (Lankford 2007).

The great constellation of Draco was seen and revered by most of the civilized cultures and tribes of the Northern Hemisphere. The Nordics shaped their great boats in the form of Draco, the cosmic dragon. The Native Americans named their tribes after it and performed many dances to represent celestial movements. The Irish Druids made good use of the symbol on their monuments. During the time that Draco’s star Thuban was the Pole Star, it may have appeared to ancient sky watchers that the Earth revolved around Draco.

Fig. 4.13. Serpent wall/snake effigy, one of two that are part of the Overlook Mountain petroform

Fig. 4.14. Serpent effigy crafted in rock outcropping on the author’s driveway

In her book The Celestial Ship of the North, E. Valentia Straiton writes, “A symbol of sacred knowledge in antiquity was a tree, ever guarded by a serpent, the serpent or dragon of wisdom. The serpent of Hercules was said to guard the golden apples that hung from the pole, the Tree of Life, in the midst of the garden of Hesperides. The serpent that guarded the golden fruit . . . and the serpent of the Garden of Eden . . . are the same” (Straiton 1992).

And Kennersley Lewis notes, “Search where we will, the nuptial tree, round which coils the serpent, is connected with time and with life as a necessary condition; and with knowledge—the knowledge of a scientific priesthood, inheriting records and traditions hoary, perhaps, with the snows of a glacial epoch” (Sacred Landscapes n.d.).

From these quotes we see that serpent worship was at the heart of humans’ earliest religious beliefs. But the concepts involved were far from primitive. Consider the mythological serpent as a representation of the constellation Draco and the tree of life as the pole or axis on which the Earth spins. Through the association of the serpent and the tree with the position of the stars relative to the Earth’s axis (precession), the importance placed on the certainty of this relationship by the ancients becomes clearer. We also can see why any disturbance in that relationship, metaphorically and perhaps literally, could portend a major imbalance in the energy and natural cycles of the universe, with the results nearly always disastrous.

THUBAN, THE ONCE AND FUTURE POLE STAR

As mentioned already, Thuban used to be the Pole Star. Due to the precession of the equinoxes, Thuban, the third star from the tail of Draco, was the naked-eye star closest to the North Pole from 3942 BCE, when it moved farther north than Theta Boötis, until 1793 BCE, when it was superseded by Kappa Draconis. It was closest to the pole in 2787 BCE, when it was less than two and one-half arc minutes away from the pole. This was at the height of the Egyptian dynastic era, and a shaft in the Great Pyramid at Giza points to Thuban, as it was the Pole Star at the time the pyramid was constructed. Thuban remained within one degree of true north for nearly two hundred years afterward, and even nine hundred years after its closest approach was just five degrees off the pole. Thuban was considered the Pole Star until about 1900 BCE, when the much brighter Kochab began to approach the pole as well.

Slowly drifting away from the pole over the last 4,800 years, Thuban now appears in the night sky at a declination of 64°20'45.6" and a right ascension of 14°04'33.58". After moving nearly 47° off the pole by 10,000 CE, Thuban will then gradually move back toward the celestial North Pole. In 20,346 CE, it will once again be the Pole Star.

INITIAL CONCLUSIONS AND FURTHER INQUIRY

It can be said that the configuration and layout of large stone constructions on Overlook Mountain, consisting of six large stone cairns and two serpentine walls, when taken as a whole, constitute a component petroform that resembles a snake or serpent. Specifically, in form and composition, the Overlook Mountain petroform bears a striking similarity to the star constellation Draco. If the Overlook petroform is not an intentional construction depicting the serpent constellation Draco, which has risen over the mountain over the course of time for many centuries, it is a remarkable coincidence. Either way, the presence of the cairns and serpent wall constructions appears to be evidence of significant cultural activity and resources related to the site.

Careful archaeological and geological inspection and analysis of the cairns and serpent walls could help provide answers as to the age and purpose of those constructions. Studying the settled and compacted soil, particles, and pebbles between the stones of one cairn and comparing them to those of others could help determine which of the structures are the oldest or the most recent. That, as well as comparing lichen colony growth rates from stones on the outer surface of the structures to those on the interior, could help shed light on when the stones were first placed in the cairns and walls. Identifying when could help determine the context within which they were built and the purpose they once served, if any.

Could this be more evidence of a diffusion of the Adena mound-building culture into the Northeast region? After all, these are mounds we are talking about, albeit mounds made of stone in the Northeast. But then again, stone would have been one of the only materials available in this region from which to construct mounds. Mounds made of stone instead of earth make sense if there are more rocks than earth, yet mounds are what you wish to build. And should we also consider, conversely, that the mound-building concept and culture of the Adena may have spread from the Northeast to the Midwest, having first arrived on our eastern shores from northeastern Europe in an early wave of megalithic migration? Until the full picture is known, this idea should not be ruled out, especially since the case for cultural diffusion and early transoceanic voyages is growing stronger with time.

It’s reasonable to wonder: were a people and culture present at the Overlook Mountain site that created rituals and ceremonial constructions of stone, exploiting and manipulating the natural environment and materials found there to express certain aspects of their belief system? Perhaps this was not uncommon. Were landscapes routinely identified and modified appropriately to create relationships between the land and the sky, to venerate and preserve symbols and events associated with celestial observation? Many examples of this have been identified and documented in the Northeast and elsewhere. To say the ancient Native civilization of the Northeast, of the Hudson River valley, and the Catskills region did not create these types of sites or recognize a serpent in the stars, in the sky, as did the ancient Eastern Indians, Chinese, Persians, Egyptians, Norse, Celts, and more, is to sell short the great thinkers and sky watchers of the early people from our own region.

As has been suggested with the serpent mound in Ohio and the sacred temples of Angkor Wat in Southeast Asia, is the Overlook Mountain serpent petroform a representation on the ground that is connected to the constellation Draco in the night sky? The crucial question of whether Draco currently or in the past appears in the night sky above Overlook Mountain has been answered; it has and does. But does it match up and align with the position of the large cairns and effigies as laid out on the ground? Is the orientation (i.e., the direction, position, layout, and configuration) consistent, matching, or close to the position of the constellation in the sky above? In shape and form I believe yes, but I don’t believe there is an actual, visual lineup and alignment based on a fixed orientation, as the ground constructions on Overlook Mountain appear to mirror the stars in the sky, creating a negative or opposite image on the ground, something not uncommon among other known ground/sky matches. But perhaps most critically, considering the precession of the equinoxes, what was the position of Draco above the site going back hundreds or thousands of years? Starry Night Pro astronomy software shows that the constellation Draco rises over Overlook Mountain to be visible high and directly above the mountain summit at various times of night throughout the year, having marked the position of true celestial north for thousands of years regardless of the drifting of precession. Further careful examination of the site could point the way to more answers.

Evidence for the veneration of the four directions, north, east, south, and west, by the Native tribes of America is well documented, dating back to before the time of the first European contact, as witnessed by many of the first European colonists to arrive. In many Native ceremonial practices, offerings are made to the four directions, relating each to a season and many times to a relative. To this group, the pre-European Native civilization of the northeastern United States, there was no more sacred and important knowledge than in which direction to face to make such offerings. Keeping track of and preserving that knowledge would have been an important task with practical as well as ritual aspects, and every opportunity and advantage would have been taken to do so. Knowing the true location of celestial north and tracking it over time would have been the key to accounting for the celestial motion caused by precession, and this may have been the single greatest undertaking of the “big thinkers” of those ancient days.

Until further evidence is found that speaks to the identity and motives of the Catskill stone mound builders, it is hard to make a stronger case for a correlation between the ground constructions on Overlook Mountain and the stars above. Further research is needed into finding out how the constellations were identified by Native northeasterners, particularly the Algonquin-speaking tribes, and whether the existence and knowledge of the serpent constellation was present in Northeast tribes’ mythology or if they identified what ancient Europeans called “Draco” as a serpentlike creature as well. Such evidence could considerably strengthen the argument for a correlation existing, a correlation between the earth and sky, between the lithic constructions on Overlook Mountain and the serpent constellation in the stars above, marking the position of the eternal, celestial north. Documenting and confirming this correlation, this serpentine connection between the real and mythical, the grounded and the godly, between human and heaven, this would surely attest to the truly sacred nature of the site and provide a crucial clue to this unfolding mystery, one most deserving of further investigation and serious, scholarly attention.