IMAGES USED IN MAGIC

From the earliest times, the idea that by means of an image or likeness, the person or animal that image represented could be influenced, has been one of the fundamentals of magical belief.

An Egyptian papyrus tells us of a palace conspiracy against the Pharaoh Rameses III, which called in the dubious aid of black magic in this way. One of the conspirators, an official named Hui, managed to steal a book of magic spells from the royal library. With the aid of this manuscript, he made wax images, with the intention of destroying the Pharaoh by their means. However, the plot was discovered, the conspirators punished, and Hui committed suicide.

It is notable that this powerful book of magic was in the royal library. Perhaps the plot failed because the Pharaoh was a better magician than his attackers; in which case their efforts would have rebounded on their own heads.

This story from Ancient Egypt is only one of many conspiracies in high places which have involved black magic, and the use of the image or puppet, made in a person’s likeness, and pierced with pins or thorns to bring about their death.

In the reign of the first Queen Elizabeth, the Court was once greatly excited and alarmed by the news that a wax image of the Queen had been found lying in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Black magic was obviously intended, because the image had a great pin struck through its breast. In those days, most people believed implicitly in the power of such things to cause sickness and even death.

Messengers were sent to summon the famous occultist, Dr. John Dee, to advise the Queen on what should be done. He went to Hampton Court, and met the Queen there in her garden by the river. The Earl of Leicester and the Lords of the Privy Council were in attendance also; and the fact that the latter had been sent for shows how seriously the affair was taken.

Dr. Dee reassured the Queen, and told her that the image “in no way menaced Her Majesty’s well-being”, which, says the record, “pleased Elizabeth well”. We are not told what was done with the evil puppet; probably Dee took possession of it, and took steps of his own to neutralise its baleful power. (See DEE, DR JOHN.)

In humbler circles, too, the image, made of wax or clay, played its secret part in spells. It is, like the burning of incense, the drawing of magical circles, and the practice of divination, part of the general heritage shared by witches and magicians all over the world.

A very frank description of this spell was given by one of the Lancashire witches, Mother Demdike, when she was examined in 1612. She confessed as follows: “The speediest way to take a man’s life away by witchcraft is to make a picture of clay, like unto the shape of the person whom they mean to kill, and dry it thoroughly. And when you would have them to be ill in any one place more than another, then take a thorn or pin and prick it in that part of the picture you would so have to be ill. And when you would have any part of the body to consume away, then take that part of the picture and burn it. And so thereupon by that means the body shall die”.

Sometimes the waxen image was melted, bit by bit, at a slow fire, to cause the person it was intended for to waste away. Sometimes, if the image was made of clay, it would have pins stuck into it, and then be placed in a running stream, so that it would slowly but surely be worn away by the water, and the person with it. This clay image was known in Scotland as a corp chreadh, and specimens of these can be found in some of our museums.

In the English countryside, the old word for these images was ‘mommets’. In France, they were sometimes called a volt, or a dagyde. The first word comes from the Latin vultus or voltus, an image or likeness. The practice of envoutement, or psychic attack, usually by means of a volt, was widely believed in, and still is. Many French books on occultism discuss it.

Cottage and castle alike feared the spell of the pierced image; and when anger and a sense of wrong burned in someone’s breast, then the peasant and the noble, even the highest in the land, might be tempted in their turn to resort to it.

There is an extraordinary passage in The Diary of a Lady in Waiting, by Lady Charlotte Bury (4 Vols, London 1838–9; a later edition by John Lane, London, 1908), referring to that unhappy woman, Princess Caroline, the estranged wife of the Prince Regent. When her husband became George IV on his father’s death, she was given the title but never the position of queen. Apparently she disliked her royal husband as heartily as he detested her. Lady Charlotte tells us:

After dinner, her Royal Highness made a wax figure as usual and gave it an amiable addition of large horns; then took three pins out of her garment and stuck them through and through, and put the figure to roast and melt at the fire. If it was not too melancholy to have to do with this, I could have died of laughing. Lady—says the Princess indulges in this amusement whenever there are no strangers at table; and she thinks her Royal Highness really has a superstitious belief that destroying this effigy of her husband will bring to pass the destruction of his royal person.

The age of materialism and scepticism had dawned in Princess Caroline’s day; and well for her that it had. Ladies-in-waiting of earlier centuries would not have felt in the least like laughing. They would have been terrified of the headsman’s block, or burning at the stake for high treason—the punishment inflicted for witchcraft directed against the Sovereign.

And can we be quite sure that the fat and self-indulgent ‘Prinny’ did not feel, at least, a few extra twinges of gout, as a result of his wife’s concentrated malice?

The facts of telepathy are accepted by many psychic researchers today, who would nevertheless sneer at witchcraft. Yet the image of wax or clay is simply a means of concentrating the power of the witch’s thought. For this reason, it is made as like the hated person as possible. in order to suggest their actual presence. So that it should have no connection with anyone else but the person it is intended for, the image should be made of virgin wax, usually beeswax; that is, wax that has never been used for any other purpose. Some old-time witches used to keep bees, in order to have a supply of wax without having to buy it, and so arouse suspicion.

When clay is the material used, the operator digs it himself—in the waning of the moon if the spell is to be directed against someone.

Not all spells with images, however, are intended for baleful purposes. Sometimes a love spell is attempted by this means; and I have seen an image successfully used by a present-day witch, for the purpose of healing someone of rheumatic pains. Of course, images of this kind would be the subject of very different ritual from that used in witchcraft of a darker shade. But the force behind the rite is the same; the power of the witch’s concentrated thought.

In September 1963 a considerable local sensation was caused when two images, one of a man, the other of a woman, were found nailed to the door of the old ruined castle at Castle Rising, in Norfolk. Between the sinister little figures was a sheep’s heart, pierced with thirteen thorns. On the ground, in front of the door, was a circle and an X-shaped cross; a sign used among witches as a conventionalised figure of a skull and cross bones. The symbols were drawn in soot. The rite was carried out at the time of the waning moon.

People in the village denied any knowledge of the matter, and assured journalists that “it must have been done by outsiders”. They admitted however, that they had heard of witchcraft being practised in surrounding districts.

The mystery remains unsolved, and eventually the interest evoked by it died down. But it flared up again four months later, when another strange discovery was made in a ruined church at Bawsey, 4 miles away. Two young lads found another sheep’s heart pierced with thorns, nailed to one of the walls. There was also a circle of soot, with a stump of burned-down black candle within it; but there were no figures.

The father of one of the boys told the police: but no clue to the identity of the person who used the old church ruins for this dark rite, was ever discovered. Less than a month later, traces of a third ritual in the area were found. This time, there was an even greater sensation; because the place where they were discovered was actually on the royal estate at nearby Sandringham.

In the ivy-coloured ruin of Babingley Church, were found yet another thorn-pierced heart nailed to a wall, another black circle of soot, another burnt-down black candle, and this time a little effigy of a woman, with a sharp thorn stuck in its breast. A young boy found the objects while exploring the ruin, and returned home to tell his father. When the father went to see for himself, he was overcome with a paralysing sensation of terror. He drove to a police station, where he arrived in a state of near collapse. It took him two days to recover from the experience.

Again the police investigated, but without any success, except to conclude that all three rituals were carried out by the same person. In this they were probably right. Three is a potent magical number; and someone in the area was evidently very determined to get results.

It is a long way from the remote Norfolk countryside to the cities of New York, Chicago or Los Angeles, with their highly sophisticated living—or is it? In the same year that the images were discovered nailed to the door at Castle Rising, an advertisement appeared in American magazines for a “Psychotherapy Kit”. It read: “This will definitely release stress and relax nerves as well as escape tension. A hex doll with four pins plus directions for use. Clever gag gift for husband, wife, boss, mother-in-law.” Other similar advertisements have described their wares as “Voodoo Dolls”; and one jokingly invited its readers to “Voodoo it yourself”.

Many mail order businesses in America sell these, and other magical supplies. In order to keep within the law, such goods are described as being merely a joke or a curio; what uses the buyers put them to is up to them.

INCENSE, MAGICAL USES OF

One of the oldest religious and magical rites is the burning of incense. The Ancient Egyptians used it extensively, and recipes for incense, composed of aromatic gums and other scented substances from nature, are found in their papyri.

Incense and perfume seem originally to have been one and the same, because the word ‘perfume’ comes from the Latin profumum, ‘by means of smoke’. That is, the scented smoke which arose from ancient altars was a means of carrying prayers and invocations, and also a sacrifice pleasing to the unseen powers.

Incense has a third very important use also; namely, its potent effect upon the human mind. Scents of all kinds have a swift and subtle influence upon the emotions. Their appeal is not only to the conscious mind, but to the deeper levels below the threshold of consciousness. Here their impact can be evocative, even disturbingly so. None knew this better than the old-time exponents of magic; much of which today would be called practical psychology.

The atmosphere created by incense and candle-light, can transform an ordinary room into a cave of mystery, a shrine wherein strange powers can manifest. If you wish to work magic, then you must create an atmosphere, both mental and physical, in which magic can work.

Some curious little round vessels, made of thick pottery, with perforations all round them, have been recovered from barrows on Salisbury Plain near Stonehenge. Archaeologists think these may have been meant for the purpose of burning incense, and have named them incense cups. If this is correct (and it is hard to see what else they could have been used for), then the burning of incense has been practised in Britain since very ancient times.

Incense as we have it today is of two kinds, and both are extensively used by occultists and witches. The first kind is that which will burn by itself when lighted, such as joss sticks and incense cones. The second variety is that which requires some already burning substance, usually hot charcoal, upon which it is sprinkled.

The latter kind of incense is generally much stronger, and gives off a bigger volume of smoke; but the former kind is easier to handle. The popularity of incense has increased a good deal in recent years, and many varieties of joss sticks and incense cones are now imported from the East. The best way to burn joss sticks or cones is the way in which the Eastern people do it; namely, to get a metal bowl, or one of thick pottery, fill it three parts full of fine sand, and stick the joss sticks or cones upright in the sand. The cones will obviously rest easily upon the sand; while the joss sticks, if stuck in far enough to be held firmly upright, will burn well and safely, look pleasing, and the ash will fall back upon the sand without making a mess.

For the stronger kind of incense, which is burned on charcoal, one can make do with a bowl of sand if one has no thurible or incense-burner; but it is better and safer to procure a proper incense-burner, or censer as it is sometimes called.

The charcoal can be bought in boxes of little square blocks, from a shop which sells church furnishings; and this kind of shop also generally sells the best type of incense, namely that made of aromatic gums. It may sound somewhat strange that witches should patronise this kind of shop; but I can assure the reader that they do, simply because they seek for incense of the best quality and most beautiful perfume.

This kind of incense, being made from gum-resins which are crushed and blended together, looks rather like fine gravel. One will need, as well as a censer, a suitable metal spoon to sprinkle the incense. The kind of censer called a thurible, which is swung from chains, is rather difficult for the beginner to handle; and I would recommend rather an Indian or Arabic incense-burner, which has a domed, perforated lid, and a bowl which stands on legs, and preferably has a metal plate for a base. This last is useful, if one wants to cense round the magic circle; because if used for any length of time, the incense-burner will become quite hot to the touch, unless there is something to lift it by.

A small pair of tongs is useful, too, if one wants to lift the lid of the censer in order to replenish it, when the lid has become hot; and also to handle the charcoal blocks without soiling or burning one’s fingers.

If the censer is a large one, it is generally a good idea to put a little sand in the bowl, for the charcoal to rest on. Then one lights the charcoal block, and puts it in the censer. The so-called self-igniting charcoal, which is mixed with a little saltpetre to make it burn more easily, is the simplest to handle. Once the charcoal, or most of it, has begun to glow, one is ready to sprinkle on the incense, and replace the lid on the censer. Then the blue spirals of scented smoke will slowly rise, and wreathe themselves about the room, twisting and twining and dissolving, with their rich perfume filling the air.

Most of the gum-resins which are the ingredients of this kind of incense are obtained from trees which grow in the tropical countries of the world. The Ancient Egyptians used to send regular expeditions into other parts of Africa, to obtain the gum-resins and rich spices they needed, for incense and for embalming. The gum called myrrh was particularly sought by them.

Other gum-resins which have been in use from ancient times are frankincense, which is another name for olibanum; galbanum; opoponax; benzoin, which in medieval days was called gum benjamin; storax; and mastic.

Fragrant woods are used also, in the blending of incense. Sandalwood is a favourite; so is aloes wood, or lignum aloes as it is often called in old recipes. Cedar and myrtle wood are sometimes used. The usual practice is for such woods and other vegetable ingredients to be dried and powdered, or at any rate to be reduced to small shavings.

The strongest vegetable odour in the world of scents is that obtained from the leaves of patchouli. Genuine patchouli perfume (which should not be confused with patchouli oil) is one of the most potent and evocative odours in the world. Like musk, it has a deserved reputation as an aphrodisiac. Powdered dried patchouli leaves are sometimes introduced into incense.

So also is powdered cinnamon. Incidentally, this easily-obtained spice, when a little of it is burnt on charcoal, has been found to make a good incense for aiding meditation and clairvoyance. Cardamom seeds are spicy and fragrant when burnt, also. The reader who cares to experiment may try discovering herbs and spices for himself, and blending incenses of his own, now that such things are easily obtainable in most large grocery stores, as a result of the greater interest taken today in herbs and condiments. He will find, however, that the scent released when a substance is burned is often different from that which it has in its normal state. Some other vegetable substances which yield perfume are mace, which is the inner bark of the nutmeg; orris root (obtainable from herbalists); saffron and cloves.

The chief perfumes obtained from the animal kingdom are musk, ambergris and civet. Musk comes from the musk-deer, which is hunted in the Himalayas. Ambergris is a substance ejected from the stomach of the sperm-whale; it looks like grey amber, hence its name. Civet comes from an African animal, the civet-cat. All these substances are very expensive; and, in their pure state, smell far from pleasant. They need to be handled by a skilled perfumer; but they are sometimes blended into expensive Oriental incense.

Innumerable writers have given lists of different incenses for different magical purposes—most of them contradictory, Probably the best course for the aspirant to magic is to experiment with the psychological effect of various perfumes upon himself. Then he can make his own list of perfumes, grading them according to their correspondences and astrological rulerships. He might, for instance, regard sandalwood as being ‘right’ for the works of Venus, frankincense for those of the sun, lignum aloes for those of the moon, and so on. As in most matters of magic, an ounce of practical experience is worth whole heaps of ‘booklarnin’.

INCUBI AND SUCCUBI

The belief in the possibility of sexual intercourse between a spiritual being and a mortal man or woman is very old, and world-wide. In Ancient Greek mythology, the offspring of such strange loves were often demigods. With the coming of Christianity, however, the subject took on a more sombre aspect. The incubus and the succubus were alike regarded as devils.

The word ‘incubus’ is derived from the Latin, meaning ‘that which lies upon’. The ‘succubus’, by similar derivation, was ‘that which lies beneath’. The incubi were regarded as demons who infested women, while the succubi debauched men.

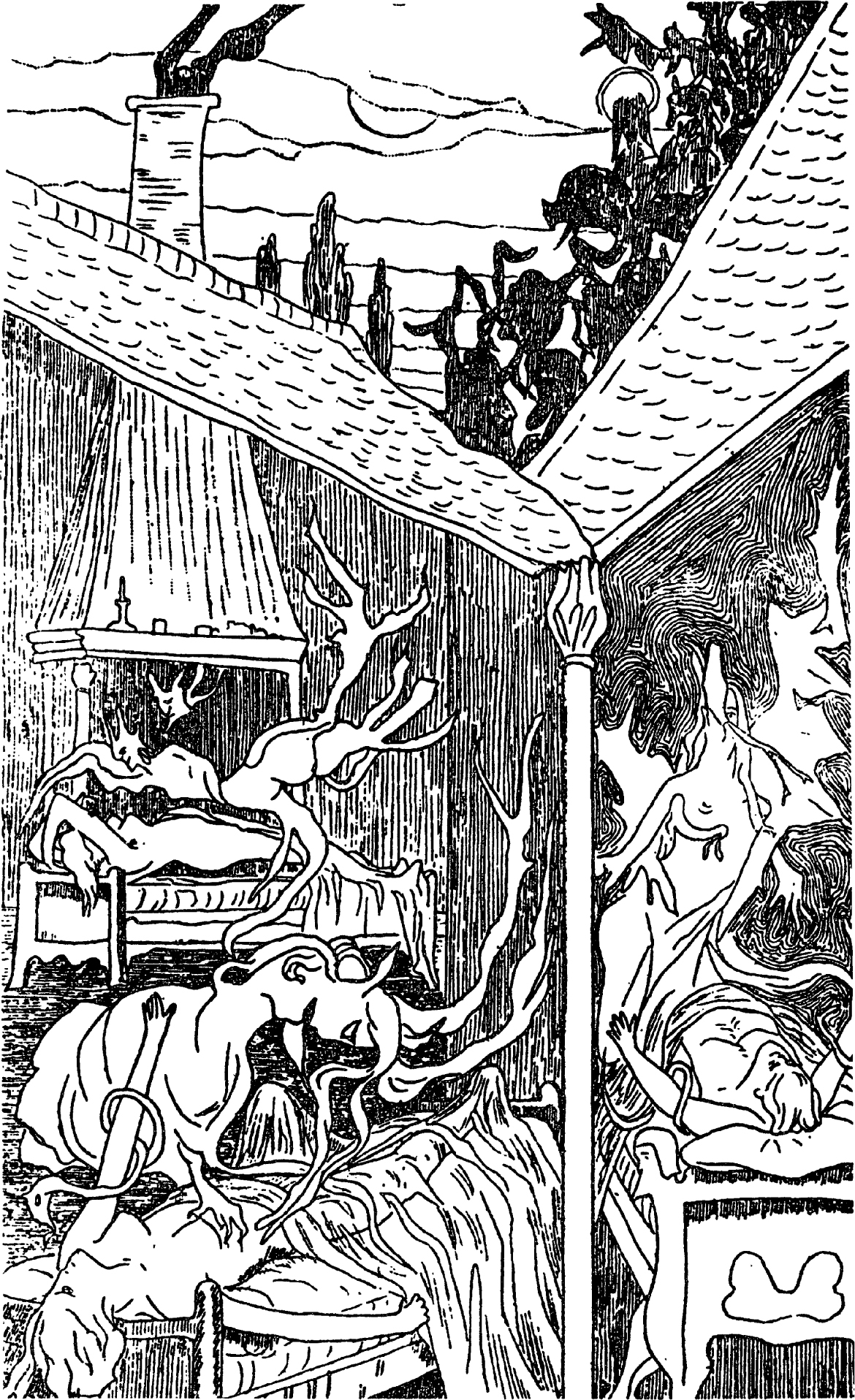

INCUBI AND SUCCUBI. A drawing from a book by the nineteenth-century French occultist. Jules Bois.

Learned doctors of the Church had much debate about the nature of incubi and succubi and of the sin involved in coupling with them. Some of them declared that the same demon, being basically sexless, because inhuman, could turn itself into an incubus to lie with a woman and a succubus to tempt a man into carnal sin. Indeed, they stated that such was a devil’s ingenuity in sexual depravity, that it could receive semen from a man by acting as a succubus, usually while he slept, and then, in the form of an incubus, convey this semen into a woman and cause her to conceive a child.

Others, however, denied that the loves of the incubi and succubi could be fruitful, and averred that their sole purpose was to cause men and women to enjoy sex, to their damnation. Still other learned Churchmen believed that devils could themselves beget children, and had done so; indeed, that Antichrist would be begotten by a devil upon a witch. This theme has been revived in our own day, in the very successful book and film, Rosemary’s Baby.

The idea of the demon-lover has appealed to many writers, one of whom, Joris-Karl Huysmans, treated it with rather more insight than most, in his brilliant and frightening look, La-Bas. Huysmans set out in this book to give a picture of Satanism as it was being practised in the Paris of his day, the 1890s; and much of what he writes is based on fact.

His hero, Durtal, is seduced into having an affair with a young married woman, Madame Chantelouve, who is a secret Satanist. She boasts to him of a certain strange power she possesses. If there is any man whom she desires, she has only to think fixedly of him before she goes to sleep, to be able to enjoy intercourse with him, or a form in his likeness, in her dreams. This power, she tells the horrified Durtal, was given to her by the Master Satanist, an unfrocked priest named Canon Docre. Later, she takes Durtal to a Black Mass performed by Canon Docre; but eventually, sickened by what he witnesses, he breaks away from her evil influence.

What is particularly interesting about this account of copulation with incubi, is that it precisely echoes another much older account, which it seems rather unlikely that Huysmans would have known about, because it comes from England.

In Thomas Middleton’s old play The Witch, from which Shakespeare quotes the song “Black Spirits” used in Macbeth, one of the witches is made to say:

What young man can we wish to pleasure us,

But we enjoy him in an Incubus?

Most of Middleton’s witch lore is taken from Reginald Scot’s Discoverie of Witchcraft, in which Scot describes the effects of the Witches’ Salve, as given by Giovanni Battista Porta: “By this means (saith he) in a moonlight night they seem to be carried in the air, to feasting, singing, dancing, kissing, culling, and other acts of venery, with such youths as they love and desire most.” (See FLYING OINTMENTS.)

There is no mention of the Witches’ Salve in La-Bas (by Joris-Karl Huysmans, Paris, 1891); however, the possibility of such experiences through sheer autosuggestion seems by no means too difficult to imagine. With regard to sexual experiences while under the influence of hallucinatory drugs, there are certain Mexican witches who make use of an unguent called toloachi. They say that women who use this ‘have no need of men’. Its composition is secret; but a main ingredient is Datura Tatula, a plant which is a relative of the thornapple.

This particular kind of hallucination, or dream-experience, seems to me to be the real basis of all the stories about incubi and succubi, without needing any recourse to demons and devils.

It may surprise readers to know that the phenomena of incubi and succubi still take place today. This is nevertheless a fact. A friend of mine, an occultist, gave me a personal account of his experience with a case of this kind.

He had been asked by a married couple to help them get rid of an unpleasant and frightening haunting, at the lonely farmhouse where they lived. Precise details cannot be given, for obvious reasons. Suffice it to say that he went to visit them, and tried sincerely to help. The phenomena had been occurring intermittently for some time, and the husband had called in various mediums and psychics, without success. The young and attractive wife seemed to be the focus of the phenomena; and my friend came to the conclusion that an earth-bound spirit was obsessing her.

On one occasion this spirit, that of a man, truculent and abusive, purported to take possession of the woman and speak through her. He gave some particulars of his earthly life, and defied my friend’s efforts to banish him.

Indeed, my friend could make no progress in the case, because he could not in practice get the woman to co-operate in anything he wanted her to do or to avoid doing. Outwardly willing, she would always find some excuse for not carrying out his instructions.

Eventually, in the absence of her husband, he tackled her about her attitude to the case. She admitted that she was not trying to get rid of the obsessing entity; because, she said, he came to her as a lover, and gave her such sexual pleasure and thrills as she had never experienced from a man.

My friend was so shocked and disgusted at the details of the woman’s confession that he abandoned the case forthwith. He said nothing to the husband, except that he could do no more and was leaving. When he told me the details of this case, he was evidently moved by genuine horror, and said that he believed the shock of what he had seen and heard had affected his health. He was in fact far from well for some time afterwards.

Such a story, of course, raises ‘many questions, both occult and psychological. Psychic researchers have encountered similar phenomena, sometimes with the added horror of alleged vampirism.

The theme of sexual intercourse with the Devil, or with a demon lover, often occurs in the confessions extorted from witches, and read during the witch trials of olden times. A great many such ‘confessions’, of course, were simply forced from the accused by torture, and in many cases people were tortured into confessing what their accusers required. One confession, however, which was made voluntarily, is that by the young Scottish witch, Isobel Gowdie, who gave herself up and was hanged. Her motives in doing so have never been fathomed; but her confession is very detailed, and includes a description of her sexual intercourse with the Devil. She says that he was “a meikle, blak, roch man, werie cold; and I fand his nature als cold within me as spring-well-water”.

This detail, of the Devil’s icy coldness, is found in the confessions of witches at many different times and places. For another instance, a witch of the Pays de Labourde, in 1616, one Sylvanie de la Plaine, confessed that the Devil’s member was like that of a stallion, and “in entering it is cold like ice, jets very cold sperm, and in coming out it burns as if it were fire”.

These descriptions are typical of a great many more, from all parts of Europe; and the details of the Devil’s cold penis and ice-cold sperm have intrigued many modern writers. Margaret Murray believed they could be explained by the Devil being a man in ritual disguise, wearing a horned mask, a costume of skins which covered his whole body, and an artificial phallus. (See PHALLIC WORSHIP.)

This explanation does in fact cover the details of many stories of copulation with the Devil. The ‘Devil’ of the coven was a man playing the part of the Horned God. Intercourse with him was a religious rite; this is why the artificial phallus was used. The Great God Pan was always potent; he was not subject to human weaknesses. The frisson which a woman would have experienced when the cold phallus entered her, was enough to produce the illusion of ice-cold sperm.

In many of the earlier accounts of sexual relations between incubi and succubi and human beings, emphasis is placed on the intense pleasure derived from such embraces. After about 1470, however, the accounts (all of course compiled and published by the witch-hunters) begin to change their attitude, and horrifying and disgusting stories are told, of how intercourse with the Devil was repulsive and agonising. As in the case of descriptions of the witches’ Sabbat, the authorities realised that it must not be made to sound attractive. Accused witches were therefore, under torture, required to assent to every farrago of sexual repulsiveness that the prurient imaginations of sadistic and repressed celibates could devise.

The authors of the Malleus Maleficarum are notably interested in the details of witches’ sexual relations with devils. This book, first published circa 1486, was the official handbook for many years of the persecution of witches. Its priestly authors give a less unpleasant description of copulation between woman and incubi than many, and one which shows the possibly auto-suggestive nature of such intercourse. They say that in all the cases of which they have had knowledge, the devil has always appeared visibly to the witch. “But with regard to any bystanders, the witches themselves have often been seen lying on their backs in the fields or the woods, naked up to the very navel, and it has been apparent from the disposition of those limbs and members which pertain to the venereal act and orgasm, as also from the agitation of their legs and thighs, that, all invisibly to the bystanders, they have been copulating with Incubus devils; yet sometimes, howbeit this is rare, at the end of the act a very black vapour, of about the stature of a man, rises up into the air from the witch.”

Given the atmosphere of the Middle Ages, when sexual enjoyment was equated with sin, and ignorance, superstition and repression ruled people’s minds, such scenes are fully understandable without the intervention of any ‘devils’, except those which existed in the minds of the participants, both the woman and the concealed ‘bystander’.

Accounts of the relations of men with succubi are less frequently met with. When they do occur, they sometimes follow the pattern of the stories of incubi. The succubus takes the form of a beautiful woman, but her vagina is ice-cold; and sometimes her lover sees her shapely legs terminating in cloven hoofs. Again, the earlier accounts of succubi present them as beautiful and passionately alluring she-devils, who appeared to priests and holy hermits in order to tempt them—an enterprise in which they were often successful. Pope Sylvester II (999–1003) is one of the Popes who is supposed to have been secretly addicted to sorcery, and legend says that he enjoyed the embraces of a succubus called Meridiana, who was his familiar spirit.

The accounts of the ice-cold body of the succubus seem to be merely imitated from those similar tales of incubi; because the majority of the stories of succubi represent them as being diabolically seductive and alluring, and even as taking the form of courtesans and prostitutes to tempt men. The Lamiae and Empusae of pagan legend were similar beings, and the origin of most of these stories seems to lie in erotic dreams, which come to men by night without their conscious volition. Mostly such dreams are pleasurable; but if feelings of guilt and the terror of sin intervene, the phantasms take on a darker tone, and the dreamer enters the realms of nightmare.

When witchcraft became an underground organisation, the Craft of the Wise, it shared a characteristic common to all secret societies. Admission to it was by initiation.

Such initiation required the newly admitted member to swear a solemn oath of loyalty. When witchcraft was punishable by torture and death, such an oath was a serious matter. Today, when witchcraft has become like Freemasonry, not a secret society but a society with secrets, the idea of initiation still remains.

Initiations into witch circles nowadays take varying forms, as they probably already always did. However, the old idea that initiation must pass from the male to the female, and from the female to the male, still persists. A male witch must be initiated by a woman, and a female witch by a man. This belief may be found in other forms, in traditional folklore. For instance, the words of healing charms are often required to be passed on from a man to a woman, or from a woman to a man. Otherwise, the charm will have no potency.

There is also an old and deep-seated belief, both in Britain and in Italy, that witches cannot die until they have passed on their power to someone else. This belief in itself shows that witchcraft has been for centuries an initiatory organisation, in which a tradition was handed on from one person to another.

The exception to the rule that a person must be initiated by one of the opposite sex, occurs in the case of a witch’s own children. A mother may initiate her daughter, or a father his son.

In general, for their own protection, covens have made a rule that they will not accept anyone as a member under the age of 21. Witches’ children are presented as babies to the Old Gods, and then not admitted to coven membership until they have reached their majority.

This rule became general in the times of persecution. Secrecy upon which people’s lives depended was too great a burden for children’s shoulders to bear. It is evident, from the stories of witch persecutions, that witch-hunters realised how witchcraft was handed down in families. Any blood relative of a convicted witch was suspect.

The witch-hunting friar, Francesco-Maria Guazzo, in his Compendium Maleficarum (Milan, 1608, 1626; English translation edited Montague Summers, London, 1929), tells us that “it is one among many sure and certain indications against those accused of witchcraft, if one of their parents were found guilty of this crime”. When the in famous Matthew Hopkins started his career as Witch-Finder General, the first victim he seized upon was an old woman whose mother had been hanged as a witch.

There are a number of fragmentary accounts of old-time witch initiations, and from these a composite picture can be built up. The whole-hearted acceptance of the witch religion, and the oath of loyalty, were the main features. There was also the giving of a new name, or nick-name, by which the novice was henceforth to be known in the circle of the coven. These things were sealed by ceremonial acts, the novice was given a certain amount of instruction, and, if the initiation took place at a Sabbat, as it often did, they were permitted to join in the feast and dancing that followed.

In some cases, in the days of really fierce persecution, a candidate was also required to make a formal renunciation of the official faith of the Christian Church, and to fortify this by some ritual act, such as trampling on a cross. This was to ensure that the postulant was no hypocritical spy; because such a one would not dare to commit an act which he or she would believe to be a mortal sin. Once the postulant had formally done such an act, they had in the eyes of the Church damned themselves, and abandoned themselves to hellfire; so it was a real test of sincerity, and an effective deterrent to those who wanted to run with the hare and hunt with the hounds. Such acts are not, however, to my knowledge, required of witches today.

One of the ritual acts recorded as being part of a witch initiation is that described by Sir George Mackenzie, writing in 1699 about witchcraft in Scotland, in his book Laws and Customs of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1699): “The Solemnity confest by our Witches, is the putting one hand to the crown of the Head, and another to the sole of the Foot, renouncing their Baptism in that posture.” Joseph Glanvill’s book Sadducismus Triumphatus (London, 1726), had a frontispiece of pictures illustrating various stories of mysterious happenings, and one of these old woodcuts shows a witch in the act of doing this.

Her initiation is taking place out of doors, in some lonely spot between two big trees. With her are three other women, one of whom seems to be presenting her to the Devil, who appears as the conventional figure of a horned and winged demon. In practice, however, the Devil of the coven was a man dressed in black, who was sometimes called the Man in Black, for this reason. The “grand array” of the horned mask, etc, was only assumed upon special occasions.

A variant of this ritual was for the Man in Black to lay his hand upon the new witch’s head, and bid her to “give over all to him that was under his hand”. This, too, is recorded from Scotland, in 1661.

Information about the initiation of men into witchcraft is much less than that referring to women. However, here is an account from the record of the trial of William Barton at Edinburgh, about 1655, evidently partly in his words and partly in those of his accusers, which tells how a young woman witch took a fancy to him, and initiated him:

One day, says he, going from my own house in Kirkliston, to the Queens Ferry, I overtook in Dalmeny Muire, a young Gentlewoman, as to appearance beautiful and comely. I drew near to her, but she shunned my company, and when I insisted, she became angry and very nyce. Said I, we are both going one way, be pleased to accept of a convoy. At last after much entreaty she grew better natured, and at length came to that Familiarity, that she suffered me to embrace her, and to do that which Christian ears ought not to hear of. At this time I parted with her very joyful. The next night, she appeared to him in that very same place, and after that which should not be named, he became sensible, that it was the Devil. Here he renounced his Baptism, and gave up himself to her service, and she called him her beloved, and gave him this new name of John Baptist, and received the Mark.

The Devil’s mark was made much of by professional witch-hunters, being supposed to be an indelible mark given by the Devil in person to each witch, upon his or her initiation. However, it would surely have been very foolish of the Devil to have marked his followers in this way, and thus indicated a means by which they might always be known. From the confused descriptions given at various times and places, it seems evident that the witch-hunters knew there was some ceremony of marking, but did not know what it was. (See DEVIL’S MARK.)

In witchcraft ceremonies today, the new initiate is marked with oil, wine, or some pigment, such as charcoal. However, as Margaret Murray has pointed out, there is a possibility, judging by the many old accounts of a small red or blue mark being given, the infliction of which was painful but healed after a while, that this may have been a tattoo mark. Ritual tattooing is a very old practice; and some relics of it survive today, in the fact that people have themselves tattooed with various designs ‘for luck’. However, when persecution became very severe, it would have been unwise to continue this form of marking.

The most up-to-date instance I have heard, of the marking of new initiates, is the practice of a certain coven in Britain today, which uses eye-shadow for this purpose; because it is available in pleasing colours, is easily washed off, and does no harm to the skin. One wonders what old-time witches would think of it!

INVOCATIONS

The words ‘invocation’ and ‘evocation’ are commonly regarded as meaning the same thing. This, however, is an error from the magical point of view. One invokes a God into the magic circle; one evokes a spirit into the magic triangle, which is drawn outside the circle. The circle is the symbol of infinity and eternity; the triangle is the symbol of manifestation.

The true secret of invocation, according to Aleister Crowley, can be summed up in four words, taken from that mysterious manuscript, The Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage. These four words are “Enflame thyself in praying”. The actual words of the invocation have little importance, so long as they have this effect upon the operator.

Crowley’s own “Hymn to Pan” (in Magick in Theory and Practice, privately printed, London, 1929) has often been used by students of magic. So have the beautiful invocations of the goddess of the moon, contained in Dion Fortune’s occult novel, The Sea Priestess (Aquarian Press, London, 1957.) These are in verse, and therefore easier to remember, poetry being a magical thing in itself. There are, however, many fine examples of invocation couched in prose. One such is the Invocation of Isis, from The Golden Ass, by Lucius Apuleius, which has been translated into English by William Adlington and by Robert Graves.

The object of invocation is a heightening of the consciousness of the operator. We do not so much call down a god or a goddess, as raise ourselves up, to a spiritual condition in which we are capable of working magic.

Many practising magicians find that the most potent invocations are those which are framed in the sonorous words of some ancient language. The invocations contained in magical books often involve strings of almost unintelligible ‘words of power’; usually the worn-down remnants of Greek, Latin, or Hebrew titles of God. An interesting example of this is the famous Magical Papyrus, preserved in the British Museum, which was translated and edited in 1852 for the Cambridge Antiquarian Society.

This papyrus came from Alexandria, and dates from about A.D. 200. Its author may have been a priest of Isis. It gives a tremendous succession of magical words, deriving from Greek, Syriac, Hebrew, Coptic and possibly Ancient Egyptian sources. It tells the magician to recite these to the North, uttering them as an invocation, with the words: “Make all the spirits subject to me, so that every spirit of heaven and of the air, upon the earth and under the earth, on dry land and in the water, and every spell and scourge of God may be obedient to me.”

Another ancient invocation is that which is preserved in a thirteenth-century play, Le Miracle de Théophile, written by a famous trouvère or troubadour called Ruteboeuf (quoted in A Pictorial Anthology of Witchcraft, Magic and Alchemy, by Grillot de Givry, translated by J. Courtenay Locke, University Books, New York, 1958). The trouvères or ‘finders’, were so called because they were poets who travelled the countryside of France in search of time-honoured lore and legend, which they incorporated into their works. They were often suspected of heresy and paganism.

This play by Ruteboeuf has a scene which involves ‘conjuring the Devil’, and it contains this extraordinary invocation, which is in no known language:

Bagabi laca bachabe

Lamac cahi achababe

Karrelyos

Lamac lamec Bachalyas

Cabahagy sabalyos

Baryolos

Lagoz atha cabyolas

Samahac et famyolas

Harrahya.

The triumphant “Harrahya!” at the end is reminiscent of the cries of the witches’ Sabbat. In the thirteenth century, ‘conjuring the Devil’ and ‘invoking the Old Gods’ would have been synonymous. So this may well be a genuine specimen of an invocation used at the Sabbat, discovered by a trouvère and perpetuated by him under the orthodox guise of being part of a miracle play.

I wished to include here a sample of a present-day witches’ invocation. However, I found it difficult to do this without giving offence to friends who preferred not to have their rituals published. So I am compelled to present an invocation I wrote myself, to the goddess of the moon and witchcraft:

Our Lady of the Moon, enchantment’s queen,

And of midnight the potent sorceress,

O goddess from the darkest deep of time,

Diana, Isis, Tanith, Artemis,

Your power we invoke to aid us here!

Your moon a magic mirror hangs in space,

Reflecting mystic light upon the earth,

And every month your threefold image shines.

Mistress of magic, ruler of the tides

Both seen and unseen; spinner of the threads

Of birth and death and fate; O ancient one,

Nearest to us of heaven’s lights, upon

Whose shoulders nature is exalted, vast

And shadowy, to farthest realms unknown,

Your power we invoke to aid us here!

O goddess of the silver light, that shines

In magic rays through deepest woodland glade,

And over sacred and enchanted hills

At still midnight, when witches cast their spells,

When spirits walk, and strange things are abroad;

By the dark cauldron of your inspiration,

Goddess three fold, upon you thrice we call;

Your power we invoke to aid us here!