I. Moscow to Barnaul and Beyond

THEY WERE MARRIED from the house of the civil governor of Moscow, a relative of Lucy’s general.

Thomas Witlam Atkinson, Native of Silkstone in the County of York in England Widower, Artist by profession of the English Church and Lucy Sherrard Finley Spinster late resident in St Petersburg also of the English Church were married according to the Rites & Ceremonies of the Church of England this 18th day of February AD 1848 by me Christr Grenside Minister Moscow.

Thus the register of the Chapel of the British factory1 in Moscow.

And we have no information as to what had happened to Rebekah, Thomas’s first wife, or indeed his two daughters by her; we only know that their son, John, had died in Hamburg. Lucy, who understood that Thomas was a widower, arrived for the wedding from St Petersburg with her charge Sofia, then aged fourteen, a testimony both to their good relationship and Lucy’s trusted position in the family.

Their stay in Moscow was short as they had to start for Siberia before winter ended – and before the roads became a quagmire. Another problem was that the Maslenitsa or Shrovetide festival meant many people were enjoying themselves and could not be found – even Nikolai, the manservant, and certainly the yamshchiks who as Lucy put it had made ‘such frequent applications to the vodky’. Then two days after the wedding a rapid thaw flooded Moscow, making sledging difficult. Nonetheless, everything was ready and, despite many of their friends urging a delay, Thomas resolved to start.

However, during Lucy’s short stay in Moscow,

it became known to the families of many exiles that I was going to visit regions where their husbands, fathers, and brothers had spent more than twenty years of their lives. Each member of these families … [who] were destined never to meet again … had some message which they wished to be delivered. Nor could I refuse them this pleasure, although it would, I found, entail several deviations from our intended route.

On 20 February (Western calendar) Thomas, his servant Nikolai and some helpers began to pack the sledge for a nearly 2,000-mile journey east to Tomsk of twelve days and nights; then all was covered with two large bear-skins.2 At 3.30 p.m. they set off, seated behind the yamshchik and Nikolai, but the snow had been melting on a sunny day, so the galloping horses sometimes had to halt on bare stone, and Thomas feared for rocks in the snow ahead. At 5 o’clock a sentinel stopped them at the gate of Moscow, an officer examined their passports, and the barrier was raised in the great archway. Lucy ‘seemed to be bidding farewell to the world … and thought of the many exiles who had crossed this barrier’, among them ‘hundreds whose only crime was resisting the cruel treatment of their brutal masters’.

Soon they were sledging fast along a straight stretch of the Great Siberian Road, and the yamshchik announced it was freezing – ‘most welcome news’. The speed of the horses and the tinkling of the bells diverted Lucy’s mind from her distressing thoughts, and on this fine night ‘star after star appeared in the firmament, till it was spotted over with its twinkling wonders’. They stopped for Lucy’s first – and memorable – impression of a post-station. It seemed deserted: all was dark. Nikolai was sent in to find someone and get new horses but did not reappear. Thomas called for him in vain and went into the post-station himself, discovering that everyone was dead drunk. He found their supposed manservant also drunk and fast asleep on a bench with his employers’ papers and bag of money on the floor. ‘He had forgotten both us and the horses,’ wrote Lucy.

After a tedious delay the officer in charge was found, and the seal and signature of the Postmaster General brought him to his senses. The officer’s whip produced some action including a search for four horses. Nikolai was severely berated and the papers and money transferred to Lucy, now ‘minister of finance’. She was not cheered to hear that they would find ‘the people drunk at every station’.

With no snow on the road ahead, the yamshchik turned into the forest. The morning found them at a post-station 112 versts east of Moscow, and Lucy had slept little and eaten nothing since their departure, so she was very pleased to see a hissing samovar brought to the table as well as their ‘basket of provisions’. They ate quickly and were soon off again. And, because much snow had fallen in the night and it had become intensely cold, their progress was now considerably faster.

They arrived at the historic town of Nizhny Novgorod and found themselves in a filthy hotel, and Lucy was appalled to find that the sledge had to be totally unpacked. Thomas had promised to call on the town’s governor, Prince Yurusov, who ‘would not hear of our leaving the town without dining’ with him and the princess. They had time to wander round the town with its churches beneath their ‘star-bespangled domes’ before turning up punctually at the dinner hour of four o’clock at the governor’s house, where they were ‘received most kindly and hospitably by the family, and … welcomed like old acquaintances’. Their hosts were surprised that Lucy ‘had the courage to undertake such a journey’ as was contemplated and even doubted if she was strong enough for it. They wanted the travellers to stay for a few days to see the places of interest, but Thomas was anxious to head to Siberia’s Altai mountains before the winter roads thawed.

Post-station. Every so often along the main or post-roads were post-stations where the horses could be fed, watered and changed, and travellers could spend the night uncomfortably on benches or the floor and get hot water but rarely food. They also had to show their travel documents – podorozhniye – in order to be allowed onwards. Travel was best in winter by sledge on the snow and worst in the thaw when the roads could be impassable.

They left the town at 10 p.m. for the frozen Volga. Lucy’s heart ‘beat rapidly as we descended its banks, it having been stated that we should find, in parts, even large holes’. Nonetheless, although ‘everything looked dark and gloomy’, Lucy slept soundly almost to the first station. The next day was extremely cold with a ‘keen and cutting’ wind, so that on arrival in Kazan, further along the Volga, Lucy found her ‘face and lips in a fearful state’ and very painful. She was assured that a piece of white muslin covering the head (standard practice at the time) would totally protect the skin from the frost, although, she noted, the Russian method of protection was ‘never to wash the face from start to finish of a journey’, as washing would dry the skin further. In Kazan, as in Nizhny Novgorod, they called on the governor, Lieutenant-General Baratinsky,3 ‘and there met a brilliant party’ and were invited to a concert by the princess, his wife.4

Beyond Kazan the roads continued to be bad. Once, while waiting for fresh horses, they found themselves breakfasting with an officer and his civilian companion, who had partaken of more vodka than tea. Lucy commented that ‘A Russian, without the slightest intention of being rude, often asks whence you come, where you are going, and your business, and some, even, what your resources are; and just as freely they give a sketch of themselves.’ The ‘cadaverous-looking’ officer, ‘now furnished with as many particulars as we chose to give’, told them he had some maps which he would be delighted to show them. The maps were produced, accompanied by ‘most significant nods and winks’ and the statement that ‘they were not permitted to be shown to any foreigner, but, out of the deep respect he had suddenly conceived for us [neither Lucy nor Thomas was a fool], he would allow us to take a peep at them’. Lucy was to add in her later book that she had bought the same maps the year before in St Petersburg. He offered to part with them for 40 roubles, then halved it to 20, both offers in vain, and then his companion, ‘the little civilian, with his sharp, foxey face’, produced a pack of cards and they both tried to persuade Thomas to play but were disgusted when he declared he did not really know one card from another.

They continued their journey with six horses, disdaining the proposal to put their sledge on wheels, and entered an area of dark pine woods. Lucy wrote that it was impossible to describe the beauty and the scenery they passed through and believed that

the nights are almost more enchanting than the days, when the pale moon is shining, and darting her soft rays down on the ever-green pine trees. In the silence of these lovely nights, as I lie back in the sledge watching every turn of the road, I conjure up all kinds of fantastic images.

On one such night Lucy noted that Nikolai, hitherto asleep both day and night, now seemed to be wide awake all the time. In fact, he had been told that there was a band of thieves ahead. He was afraid to sleep, but Thomas prepared for trouble by reloading his pistols and checking his gun. However, it proved a false alarm and their ‘own solitary sledge was the only thing on the road’.

At last they reached Ekaterinburg, the chief town in the Urals, on 6 March (no entries in Thomas’s journal5 until 21 March – he had, of course, done the same journey the previous year – so Lucy must be relying on her memories or perhaps kept a journal herself) and accepted the offer of hospitality from an English friend of Thomas’s from the year before. Meanwhile, Nikolai had been sacked for ‘neglecting duty and gross misconduct’. He was ‘not to be trusted, and Mr Atkinson had always treated him with great leniency’. When in Moscow he had received enough money to buy everything he would need ‘for a journey of two years’, according to Lucy. Presumably that was all that was envisaged at that time. Just before they left Moscow Nikolai astonished Thomas by asking for more money, although he had already received a year’s salary in advance. Thomas refused ‘until he said he wanted to buy something for his “old mother” – he might have known his master’s weak point’. But on arrival in Ekaterinburg they found that Nikolai had loaded in the sledge a lot of items to sell and was already ‘occupied in disposing of them’, while the poor ‘old mother’ received nothing.6

As it was Lent, the place was quiet and there were few dinner-parties, although the Atkinsons attended one at General Glinka’s, now head of the Urals’ mines.7 While in Ekaterinburg one of the British inhabitants, Peter Tate, a mechanical engineer,8 presented Lucy with a rifle to add to the pair of pistols that Thomas had bought for her in Moscow, ‘so now we have each evening rifle and pistol practice, as it is advisable for me to be at least able to defend myself in case of an attack being made on our precious persons or effects whilst travelling amongst the wild tribes we shall meet with on our journey’.

And Lucy was told many stories of ‘robberies and fearful murders’. One in particular happened during a previous Lent when a father and son had been travelling on the route that the Atkinsons intended to take. One late night they stopped at a peasant’s house with only one room and, when all the family had settled down on the stove-cum-oven which serves as a bed and the two travellers had eaten the supper of cold meat they had brought with them, they went to sleep on the benches. Soon, Lucy writes, a man on the stove

slid gently down, and, taking in his hand a hatchet, …with cautious steps approached the sleepers, and, lifting the instrument with both hands, brought it with such force down upon the head of the poor father, that he literally cleft it in two; he then turned to the son, … and despatched him likewise. The brutal murderer then returned to his berth and slept till morning.

The reason he gave the authorities for these two murders, according to Lucy, was because they had committed ‘the awful crime of eating meat in Lent’, and, though he knew it was a crime, ‘a voice kept continually urging him on … saying that he was only putting an end to sin’. Thus, ‘to prevent such a fate’, and knowing they would take the same road, Thomas was presented with a hatchet by the kind gentleman who told them the story.

For their journey ahead Peter Tate’s wife ‘prepared provisions of all kinds for us, as there was nothing to be procured on the road, especially during the fast’, but Lucy speculated that in a few months’ time they would not be too fastidious about eating peasant food. She already enjoyed ‘amazingly’ black bread which they could get at any ‘cottage’, but they took with them a good supply of white bread as well as butter.

Four days after leaving Ekaterinburg they reached Yalutorovsk in Siberia (Lucy spells it as ‘Yaloutroffsky’) off the great post road, for the first of their meetings with the exiles of the Decembrist conspiracy of 1825. Here they had a gun for ‘Mouravioff’ as Lucy calls him: Matvei Ivanovich Muravyov-Apostol (1793–1886), a distant cousin of Lucy’s former employer in St Petersburg. He ‘seemed to be in the prime of life’ and when Lucy told him her maiden name (Finley),

I was instantly received with open arms; he then hurried us into his sitting-room, giving me scarcely time to introduce my husband. I was divested of all my wrappings, although we stated that our stay would be short; he then seated me on the sofa, ran himself to fetch pillows to prop against my back, placed a stool for my feet; indeed, had I been an invalid, and one of the family, I could not have been more cared for, or the welcome more cordial.

He sent at once for one of his comrades-in-exile, whose family Lucy also knew (perhaps Yakushkin),9 and the widow of a third Decembrist with her two children.10 Lucy had many messages to pass on as well as small gifts for everyone. One message for the widow was to part with her children so that they could get a proper education. She would think it over, she said, and all present urged her to consent for the children’s sake. She did, in fact, do so, and the children went to an aunt in Ekaterinburg whom the Atkinsons knew a little and who would give them great affection. ‘Poor mother!’, sympathised Lucy: a great pang of parting, but it showed her great love for them.

There was ‘quite a little colony’ of Decembrist exiles in this small place, ‘dwelling in perfect harmony, the joys and sorrows of one becoming those of the others; indeed, they are like one family’. Lucy was to point out in her book that ‘the freedom they enjoy is, to a certain extent, greater than any they could have in Russia’, thus full liberty of speech, and ‘the dread of exile has no terror for them’. On the other hand their movements were restricted, although lenient local authorities allowed keen hunters remarkably full freedom, which was not abused.

Muravyov-Apostol, the Atkinsons’ host, was ‘a most perfect gentleman’, Lucy considered,11 and the long years of exile had evidently not changed ‘his indomitable spirit; there was nothing subdued in him’ despite having been sentenced ‘as one of the most determined of the conspirators’ to an originally two-year solitary exile in the marshy forests of the Yakut province, the coldest part of Siberia, with the coarsest food, no books or writing materials and under rigid supervision. To the official enquiry how he was spending his time the answer came, ‘he sleeps – he walks – he thinks’.

Their host told them that on his long journey into exile the officer in command relaxed his authority after some distance from Moscow and treated his well-educated charges as associates, inviting one or two to share his meal. At one stop, the officer was breakfasting with Muravyov-Apostol and left the room to ensure departure was in hand, leaving his exile companion sitting inside at a table. A village official came in through the particularly low door and bowed humbly before the seated gentleman whom he took for the officer.

He then entered into conversation which naturally turned upon the scoundrels … being conveyed into exile, and (continued this man, looking into his face,) ‘there is no mistaking they are villains, of the blackest dye; indeed, I should not like to be left alone with any of them, and, if I might presume to offer a little advice, it would be to observe well their movements, as they might slip their chains, and not only murder you and all the escort, but spread themselves over Siberia, where they would commit all kinds of atrocities.’ At this point of the conversation, the bell rang to summon them all to depart,

whereupon Muravyov-Apostol stood up and, when his visitor heard the clanking of chains, he looked totally aghast and, Lucy says, seeing ‘the object of his terror about to move forward, he made a rush at the door, but, not having bent his head low enough, he received such a blow that it sent him reeling back into the room and sprawling on the floor; but he picked himself up quickly and bolted’.

They found Yakushkin was the most isolated of all the Decembrist exiles they encountered, his home ‘as scantly furnished as the abode of a hermit; but books, his great source of delight, he had in numbers’. Having announced (surely unreasonably) that they could not stay long, the Atkinsons were still with their new Decembrist friend in the evening and left reluctantly, taking a present from him of three books, inscribed simply with the date and ‘Yaloutroffsky’. (Where are they now, one wonders?) Thomas and Lucy promised to spend a day or so with these Decembrists on their return journey, but these were by no means the only ones they would visit.

They now travelled on quickly over good roads – to start with at least – and Lucy developed a useful technique for getting horses without delay. Their friend in Ekaterinburg, Mr Tate, had given her a horn in case she got lost in the mountains yet to come and, as they arrived at each post-station, she would blow the horn ‘when out rushed all the people to know who it was, it was capital fun, and gave great importance to our arrival; indeed, they were so amused that we obtained horses, without the slightest difficulty or delay’.

Sometimes they got stuck in deep snow and had to get help from local villages, and the landscape became a ‘white waste, with a cold cutting wind’. Then, nearing Omsk, the roads became totally snowless. They reached the town at 4 p.m. on 8 April, a six-day journey from Ekaterinburg, and drove to the police-master’s house since they had a letter for him from a mutual acquaintance whom they had met on their journey. After a furious reception by the police-master ‘in a dirty, greasy dressing-gown’, when Thomas had the temerity to have had him woken from his siesta – lessened only somewhat by him presenting his official papers – a Cossack had them taken to the town’s outskirts ‘to a most horrible place’ where they had to go through a room where men were ‘lying [on the floor] stretched out in all directions, some smoking, and others talking at the utmost pitch of their voices’. They were given a cold room but managed to get a fire going and found food in their sledge to assuage their hunger ‘and were glad to spread the bearskins on which to stretch our cramped and bruised limbs; for six nights I had not had my clothing off’, wrote Lucy.

Next morning they called on Prince Gorchakov, Governor-General of Western Siberia,12 with Thomas’s official letters; and the request for an escort in the Kirgiz steppe which the Atkinsons hoped to visit was mercifully granted. Interestingly, the Tsar had given permission only for travels in the Urals and the Altai, but that presumably gave Gorchakov enough confidence to grant a simple request as the supreme authority in West Siberia. He was very angry on learning of their accommodation overnight and gave orders for ‘proper quarters’, of which the police-master oddly took no notice. But one hour after a second order Lucy ‘was comfortably lounging on a sofa in a general’s quarters’. It is intriguing that the two Atkinsons from their modest backgrounds were mixing with high society, doubtless because of Thomas’s official letters authorised by the Tsar, and Lucy’s former high-ranking employer had probably presented the pair with a general letter of introduction or even individual ones to high officials. Perhaps Lucy had learned how to behave in her employer’s grand household, if not before, and Thomas’s innate intelligence and charm got him to copy ‘his betters’ and be accepted by them.

Next day Thomas went to Gorchakov for ‘his papers’ accompanied by Lucy who ‘went also to take leave of him’ and was invited to dine as well if ‘she would excuse the presence of a lady’. Leaving for Tomsk that evening, Thomas greatly feared that the frozen rivers would break up before they arrived. When they reached the town of Kainsk13 he hoped to find his dog, which had strayed following a pack of wolves, on his return to Moscow on his previous journey in a hurry to see Lucy again. Since the dog was a favourite, the post-master had been instructed to take care of her if found, but Lucy ‘had a kind of wish that we might not find her, as I had been told she slept in the sledge, and I had fully made up my mind that no dog should sleep in a sledge with me’.

On reaching Kainsk, Thomas whistled and, on cue, the dog, whose name was Jatier,

came bounding over the top of the low hut, disdaining to walk through the gate. As I [Lucy] looked at her I thought I never saw anything so beautiful; she was a steppe dog, her coat … jet black, ears long and pendent, her tail long and bushy; indeed, it was a princely animal; the red collar round her neck contrasted so prettily with her coat, and then to see the delight of the poor beast as she leapt into the sledge; I do not know which was happiest, dog or master … but the dog never once annoyed me by entering the sledge; when tired with running, she used to occupy Nikolai’s [former] place beside the driver.

One night, tired out by ‘continued shaking and bumping on the bad roads’, they were both fast asleep when they were woken by the dog’s growling. They found the sledge had stopped in the middle of the forest and two of their horses and the driver had gone, replaced by four strangers. Thomas leaped out of the sledge, called out for the driver in vain and ‘demanded horses of these men’ who insolently told him to get some at the next post-station. ‘There was no mistaking into what sort of hands we had fallen.’ The men approached and began to unharness the remaining horses, but Thomas told them, doubtless through Lucy, that he would shoot the first person who tried to take them. This had no effect, so Lucy ‘passed him his pistols, the click of which, and his determined look’ brought them to a halt. They then started to move into the forest, but Thomas said he would shoot the first man who stirred. When they claimed they were only going for horses, he told them one man was enough. After much talk, with Thomas and Lucy guarding the sledge, and Jatier continually barking, tail erect, one man went off and reappeared shortly with two horses, and they were soon able to proceed – Lucy noticing their absent yamshchik ‘peeping out from behind the trees’ who had failed in his attempts to rob and perhaps murder them.

On their way to Tomsk there was sometimes no snow and how they sledged on was a mystery to Lucy. They had to cross the river Tom and climb its bank before reaching the town, and ‘the water was so deep on the ice that we feared everything in the sledge would be spoiled’. They were ‘right glad’ to arrive in Tomsk and Lucy believed ‘it requires a pretty strong constitution to endure for days and days together’ the rough travelling they had known: a succession of almighty bumps for ‘versts and versts’, so that ‘the sledge is not smashed to atoms is a wonder’.

They were told that the poor couriers lived only a few years. Once in Tomsk, they were intrigued by the town’s dining-rooms, established by a dwarf albino (probably British) and his wife, a German giantess: members of a circus travelling through Siberia who, tired of their lives, had married and settled down in Tomsk; the dining-rooms they ran relied on her excellent cooking and his very own brand of port.14

The Atkinsons were delayed in Tomsk, ‘it being impossible to travel either by winter or summer roads’ due to the thaw, and the post had stopped as the rivers could not be crossed. They arrived in the last week of the Easter fast, just in time for the festivities. But first, Lucy went (rather oddly on her own) ‘to make the acquaintance of all the notables of the town’, mainly what she calls ‘gold seekers’, presumably gold-prospectors and goldmine merchants. One of the richest of the latter, Ivan Dmitrievich Astashev (1796–1869), whom Lucy spells as ‘Astersghoff’,15 showed them ‘some fine specimens of gold, weighing 25 lb and 30 lb each. These miners have magnificent mansions, and live in great state.’ They visited the vice-governor, ‘a most amiable and gentlemanly man’ who, however, would have to leave his post as he had just married a gold-prospector’s daughter and in consequence owned goldmines, forbidden to a government official. His wife was the only child of a poor peasant whose mother had died when she was very young and who ran about the streets shoeless for years. Fortunately her father found a rich mine and could now send her to school ‘where she learned to read and write’. He had died two years before the Atkinsons arrived, Lucy noting:

[he left] his daughter a rich heiress at the age of fifteen; her education is still being continued; her husband has provided her with teachers, who come daily. A more graceful or beautiful creature it has rarely been my lot to see. She receives her visitors and sits at the head of her table, as though she had been accustomed to her present position from her birth, and yet so modest withal.

The Atkinsons found two Englishmen in Tomsk. One was a Dr King,16 practising in Tomsk and certainly not the first doctor from Britain in Siberia. (The first may have been Dr John Bell two centuries earlier, who accompanied a diplomatic mission from Peter the Great to the Emperor of China and has left an engrossing account of his journey.)17 The two visitors spent ‘many agreeable hours with him and his wife’. The other (unnamed) Englishman had been exiled for forgery, evidently unjustly, for it seemed he was innocent, ‘but bore the blame for another, never supposing it would lead him into exile; that other never came forward but, it is said, basely deserted his friend’, as Lucy writes. The exile was ‘now living a most unexceptionable life, respected by all and in a position of great trust’.

The balls and dinner parties the Atkinsons attended were ‘conducted’ in much the same way as those in Moscow and St Petersburg except for the wives of the wealthy miners, dressed in good taste but wearing ‘a perfect blaze of diamonds’. But there was one exception: a dinner party for forty in the house of a rich merchant. The archbishop was the guest of honour and champagne was liberally provided, but the hostess, Lucy notes,

devoted to her distinguished visitor, … took care that he was well plied with English porter as well as wine, which he appeared to appreciate, if one might judge from the quantity he imbibed, and there was not the slightest difficulty in inducing him to do so. Dinner went on smoothly enough till the sixth course, fourteen was the complement,18 when the archbishop decided to rise, having already more than satisfied himself that the dinner was in every way excellent.

The hostess was appalled, knowing that, if he left, the other guests would do so too, and got him to sit down and begin eating and drinking again ‘as though he had been deprived of food for months’. ‘As for conversation, he was too much occupied for that’, despite Thomas’s valiant attempts sitting next to him, except for ‘a few coarse jokes which, unfortunately, are everywhere tolerated in Russia’. By eight courses, the archbishop decided that everyone should be satisfied, but the hostess, alarmed again, ‘was at his side in a moment; his leaving the table was not to be thought of, he must at any cost be made to sit still’. The dinner was little more than half over and it had taken days to prepare with no expense spared, so he was ‘coaxed and persuaded like a spoiled child to sit still; but he would no longer eat, only drink’ and sat sullenly while ‘the hostess whispered soft soothing words into his ear’ and scarcely left him. He ‘gradually lay back’ and dropped asleep. Both hosts and guests were greatly relieved, and the hostess could now continue to wander round, as was her custom, ministering to her other guests. Fortunately ‘the noise of the revellers’ mitigated the sounds from the head of the sleeping archbishop.

When all was at an end, no one took any notice when two guests helped him out, and a few days later Thomas received an invitation from him, as he wished to see some of his pictures, and sent men to collect them. Thomas’s response was that ‘if his reverence would call he should be happy to show him any drawings he had, but he never carried them to anyone, excepting to the Imperial family. The archbishop was, as you may judge, mightily offended.’

In mid-June (1848) the Atkinsons visited all their friends in Tomsk to say goodbye, and the Astashevs (he of the goldmine) called and presented Lucy with a very fine gun made by Orlov, one of the leading St Petersburg gunsmiths. Thomas finished his drawings of Tomsk19 and packed them ready for their journey some 400 kilometres almost due south to Barnaul, the principal town of the Altai. He ordered the horses for 4 a.m.,20 and, he wrote in his journal,

Away we went having a splendid morning for our journey. The water in the Tom was still very high but at 10 o’clock we had crossed without accident and then our road crossed the valley, at this time one sheet of deep Orange Colour from the great quantity of Globe Anemony in some places. The pale blue forget-me-not covered the ground in large patches, while numerous shrubs gave forth their blossoms quite scenting the Air. Altogether it was a scene of Loveliness I had never beheld – on reaching the woods we found the ground covered with deep purple Iris and many other flowers quite new to me. Mrs A enjoyed the ride greatly. The views of the Town where [sic] greatly changed since we passed over the Ice when all was snow and frost.21

They made great progress during the night, ‘but now began our difficulties in crossing the rivers which were all flooded and deep…. Oh, what a change since I passed over this road in January with forty-three degrees of Frost. Now the ground was covered with Luxuriant plants, and flowers of every colour but in places we still found snow’ (this in mid-June).

A breakdown in the morning delayed them and in the evening they found a stream difficult to cross and then encountered some very bad roads in the night.22 But the next morning,

A fine Sun rise made every thing look fresh and gay [and] at 12 oclock we arrived on the Banks of the River Ob now about two versts broad and runing fast. It was no easy matter to get the carriage over some of the pools, the water runing over the Axles…. Having dined, we started on in the hope of reaching Barnaoul to dinner tomorrow…. Traveled on very well through the night.23

They stopped at 6 a.m. to breakfast and were warned they would have difficulty in proceeding as the Ob flood-waters covered the way ahead for a long distance. So they had six horses harnessed in the hope of success, and after a few versts reached the Ob and drove along its high bank from which they

had a splendid view. The River had over-floun the valley in places more than twenty versts broad, the groups of Trees looking like small Islands in a large Lake. On descending into the valley we had the water up to the bottom of the carriage, no very pleasant prospect feeling that every step might take us into deep water.… I [NB, not ‘we’] found it was impossible to cross, the mud was so high. There was not a place to put our heads in, only our carriage; a great Thunderstorm was ragin at a short distance but here we must stop the night and that too with only dry bread to Eat and a bad night to look forward too.24

After passing a most uncomfortable night we turned out with the Sun. I urged the boatmen to take us over without delay – at 4 oclock we embarked and got over in three hours the stream running fast. On reaching Barnaoul we drove to My Friend Stroleman’s [one of the officers of the zavod], accepted a kind invitation to stay and were soon making a good breakfast after our long fast.25

They were now in the Altai, a region called after one of the largest mountain systems of Central Asia, extending south into Mongolia, although in fact ‘the Altai’ also embraces extensive fertile steppe in the north-west. The mountains are not just one range, however, but a confusion of at least twenty-five different ranges,26 set at many different angles and separated by gorges and river valleys. Surprisingly, each range and each valley has its own micro-climate, differing sharply from that of its nearest neighbours. The three highest ranges are covered with eternal snow and glaciers, and from the glaciers below the highest peak, Belukha (4,506 m), flows the Altai’s longest river, the Katun, 665 km long, with its swift current and many rapids, finally joining the Biya to form the great Ob and later joined in turn by its massive tributary, the Irtysh. Both start in the Altai and flow on north together to the Arctic Ocean as the Ob-Irtysh river system, one of the longest in the world.

Map of the Altai Mountains

But traditionally the Altai mountains are not just physical mountains. They have great mystical resonance and have been called ‘the spiritual axis of the world’, the location of Shambhala itself, the meeting place of heaven and earth, a mystical and mythical paradise of Tibetan Buddhist legend, the world’s holiest place. These beliefs led to the theosophical works and intensely coloured paintings of Nikolai (1874–1947) and Elena Roërich who travelled in the 1920s through Tibet, Mongolia and the Altai mountains looking for Shambala. James Hilton’s best-selling Lost Horizon (1933) positioned Shambala in Tibet as Shangri-La.27 Myths notwithstanding, the indigenous Altaians,28 whom the Atkinsons knew as ‘Kalmucks’,29 regard Belukha, the Altai’s highest and eternally snow-covered mountain, as particularly holy.30

Certainly legends have had time to develop here. Those great Altai plains north-west of the mountains have been inhabited for thousands of years by nomadic peoples, and Siberia’s permafrost, subsoil permanently frozen since the ice age, has preserved – it would seem miraculously – the kurgans or burial places of tribal chiefs, the most famous the 5th–3rd-century BC Pazyryk valley burials of the Scythian iron age. The Atkinsons, particularly Thomas, may indeed mention ancient barrows and stone monuments, but the first Pazyryk site was discovered only in the 1920s; the tombs revealed superbly preserved fabrics including the world’s oldest pile carpet, an intact funeral chariot, horses and a chief’s tattooed body. And in 1993 the fifth-century BC so-called Ice Maiden or ‘Altai Lady’ was found, also tattooed, accompanied by six sacrificial horses. The grave had been flooded and frozen ever since, so all was immaculately preserved including her yellow blouse and white felt stockings.31

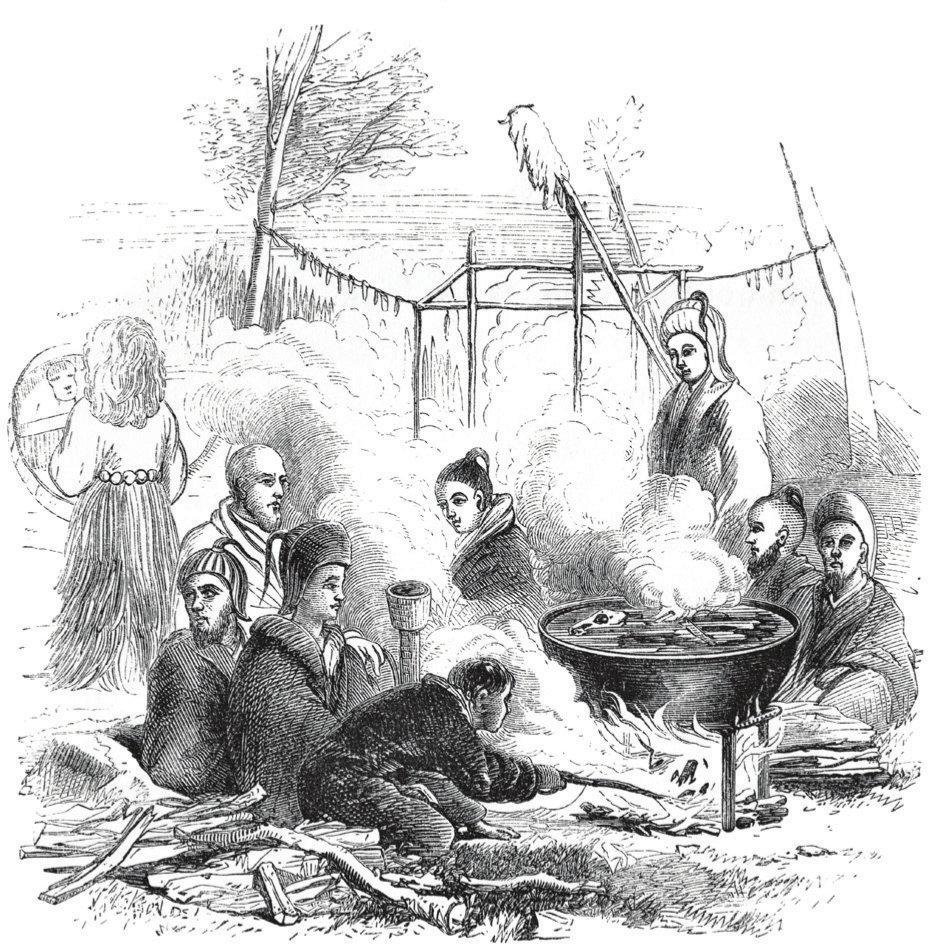

Kalmyk sacrifice

Thomas witnessed a Kalmyk sacrifice at which a ram was killed and flayed, its skin put on the pole and the flesh cooked in a great cauldron while a shaman chanted and beat his tambourine.

Barnaul, the chief town of the Altai where the Atkinsons now found themselves for a whole month, lay on the left bank of the Ob, and had wide grid-patterned streets built on deep sand. Like most Siberian towns of the time, it was constructed almost entirely of wood, with many people living in izbas (small log cottages); only a few buildings, including three simple churches, were of brick, but the town could boast a gostinny dvor, equivalent to a coaching inn, with some good shops where many European items were on sale at high prices including watches and jewellery, French wines and silks, muslins and bonnets, sardines, cheeses, English porter, Scotch ale, swords, guns and pistols. There was also a good market supplied by the local peasants, almost all of whom kept cows and horses, and there the Atkinsons found the prices, on the contrary, astonishingly cheap: thus a pood of beef could be bought (at today’s equivalent) for 40p, a pood of salmon for 30p and a hundred eggs for 20p (although further east food prices were much higher).32

The town’s population at that time was under 10,000, including the 600–800 soldiers usually stationed in the barracks. Since Thomas’s previous visit he had, he claimed, visited almost every Siberian town (far fewer than today) ‘but in no town have I found the society as agreeable as in Barnaoul’, which a few years later a visitor, the outstanding geographer and explorer Pyotr Petrovich Semenov (later honoured with the appendage ‘Tyan-Shansky’, 1827–191433), called the ‘Athens of Siberia’. He found, says Lucy, ‘an excellent band … [which] executed most of the operas beautifully’ under the baton of a St Petersburg-trained musician. Three ladies played the piano well and the winter saw three or four amateur concerts ‘which would not disgrace any European town’ as well as several balls which many young mining officers would attend, back from their posts in the Altai mountains.

Perhaps the place was exceptional because of the number of highly educated mining engineers based there, and the Atkinsons have certainly left us an interesting picture of its social life in the 1840s. Each family had to lay in their stores to last a whole year: ‘woe betide the unlucky mortal who may have miscalculated his or her wants’. For every February the principal families would have to give the town’s obliging apothecary a list of what they needed together with the necessary funds, and he would buy the items as well as the government stores at the great annual fair in Irbit, just east of the Urals, so that on his return journey he seemed like ‘a wealthy merchant with a large caravan’. Lucy found that the ladies spent part of the mornings helping the governesses (yes, in Barnaul) educate the children and prided themselves on superintending the housekeeping.

The domestic arrangements of a house … are rather a weak point with me. I never lose an opportunity of seeing all I can in this way; so into all the store rooms I went … [and found] groceries of every kind and description, with bins fixed round the room to contain them; then there are tubs of flour, boxes and boxes of candles [necessary before electricity] … and the neatness which prevails here, as in every other part of the house, was pleasing to see, and cleanliness reigned supreme.

The Atkinsons spent many a pleasant evening in Barnaul homes and on Sundays dined with the Director of Mines as did all the officers.34 After dinner, Lucy says, all went home for a siesta ‘without which I do not believe a Russian could exist’ and in the evening between seven and eight the officers returned, now accompanied by the ladies. The younger ones would dance, the older ones play cards, at eleven supper would be placed on the table, and all would be home by midnight.

On Wednesday evenings one of the officers would entertain ‘the little circle of friends’ where the men played chess or cards and the ladies took their handiwork. Lucy found the first such evening ‘a most agreeable one. I immediately felt at home, and as though I had known them for years. The time passed merrily.’ Later, the ladies begged Lucy to bring Thomas in with her and then she saw ‘how much he was beloved by them; when he sat down they formed a circle around him, and told him he was the life of their Wednesday evenings’, while on Friday evenings the two foreign visitors met under another roof for yet more enjoyable hospitality. ‘What renders these meetings so agreeable’, thought Lucy, ‘was the simple and unostentatious way in which the people assemble together.’ Moreover, almost every day in the summer someone organised a picnic, primarily for the children. ‘The servants35 are despatched beforehand with all the necessary apparatus for tea, and right merrily do all pass their time.’ Young and old joined in games followed by ‘charming walks in the woods’ to pick mushrooms, wild fruit and flowers. On other days the men had shooting picnics, and Lucy found it ‘mysterious’ how they consumed all the wine they took with them ‘and it often happens that a man returns twice or thrice for more champagne’.

One beautiful June day the Atkinsons attended a ball to celebrate the name-day of Madame Anosov, the wife of the Governor of Tomsk. It was therefore a special occasion. All dined at the General’s at 2 p.m., the normal dinner hour, and there was dancing till late, interspersed by refreshments and strolls through the large gardens and ‘really beautiful fireworks’; the whole day was ‘one scene of gaiety’.

Thomas calls the General ‘one of the most skilful and ingenious metallurgists of the age’. For many years he had run the production of steel here with a large blast-furnace, forging mills and all the processes to make steel. He had also designed the three-storeyed fire-proof workshops to forge swords, sabres and helmets; Thomas had not seen ‘either in Birmingham or Sheffield any establishment that can compare’. Anosov had also, ‘with much skill’ and ‘untiring assiduity’, rescued from oblivion the long-lost art of damascening blades and perfected it. In the summer of 1847 he was made Governor of Tomsk and Chief of the Altai mines. Every year he would leave his many duties in Tomsk as Governor to spend three or four months in Barnaul, the administrative centre of the mines.

Below Anosov was Colonel Sokolovsky,36 the Chief Director of Mines, in charge both of the mining officers and some 64,000 people in the mining areas. They were lucky to have two particularly able men in charge. Sokolovsky was not only a very experienced administrator but a well-known mining specialist and author of many scientific papers on the subject.37 He had to travel each year more than 6,000 versts, mostly in mountain areas, by carriage, horseback, raft, boat and canoe, to inspect all mines and smelters. And annually between May and mid-October eight or ten young mining officers would be sent off, each with forty to sixty men, to explore closely the particular area assigned to them, each party provided with a map, dried black bread, tea, sugar and vodka, while they had to hunt their own meat – not difficult for the good hunters in each party.38 Virtually all Siberia’s gold would be brought to Barnaul for smelting and to be cast into bars which left for the St Petersburg mint, guarded by soldiers, twice in summer and four times in winter on the faster sledge roads, Thomas writes.

He was impressed both by the condition of the Altai’s miners – in his experience ‘more wealthy, cleanly, and surrounded with more comforts, than any other people in the [Russian] Empire’– and by the mining engineers themselves,

pre-eminent at the present day. No class of men in the Empire can approach them in scientific knowledge and intelligence. Among them are many in these distant and supposed barbarous regions who could take their stand beside the first savans [sic] in Europe as geologists, mineralogists and metallurgists.

Barnaul’s distinction lay in being the main town of the Altai’s immensely rich mineral deposits – copper and gold,39 but particularly silver. A hundred years earlier the Crown had taken over the mines and metal works, and 90% of the Russian empire’s silver soon came from the Altai, with its largest silver-smelting works in Barnaul. Thomas found the Mining Administration and all its officers lived here and, calling on Sokolovsky to present his papers, learnt that instructions had been received about him from the Ministry in St Petersburg (more than 4,500 versts away). The Colonel spoke a little English and had ‘a most amiable’ wife, and it was soon clear to Thomas ‘that civilisation of a very high character had reached these regions, united with great kindness and genuine hospitality’. Sokolovsky as Director showed him round the silver-smelting works and the furnaces for gold-smelting (although these were not operating at the time), gave him a route allowing him much potentially interesting travel, letters to some of his officers at Altai mines and, most important of all, a Cossack guide who knew the region ahead very well.

He found the Ob ‘a magnificent stream’ in a valley twelve versts wide, split into many branches where large trees grew on islands. In June, the meltwater not just of the plain but of the Altai mountains to the south usually covers the entire valley between its two high banks. Only the tops of trees rise above the vast volume of water which moves slowly but relentlessly more than 2,250 miles (3,500 km) north across the great – and almost flat – West Siberian Plain towards the Arctic Ocean.40 That year, 1848, saw the Ob unusually high so, unable to travel further, Thomas accepted an invitation in early July from Sokolovsky to join two others (and three dogs) in shooting double-snipe (Gallinago major) in the Ob valley, where ‘thousands’ could be found on the banks at that time of year. In less than three and a half hours Thomas had (with no dog) shot twenty-three, Sokolovsky forty-two, Barnaul’s apothecary sixty-one, and Thomas’s ‘little friend from the Oural’ seventy-two – henceforth known as Nimrod, ‘the mighty hunter’ – a total slaughter of 198 birds, according to Thomas’s reckoning.

Thomas presented Lucy to all his friends in Barnaul from his previous visit, including the wives of General Anosov and Colonel Sokolovsky, and ‘she was most kindly received by all’.41 Next day the Colonel called, inviting them both to dine – ‘we spent a few hours with them very pleasantly’ – and Lucy gave their host Thomas’s view of the Altai’s Lake Kolyvan (which he had visited the previous year) as a thank-you for the loan of his sledge, which had taken Thomas to Moscow and now brought him back with Lucy.42 And after dining next day with General Anosov, they gave him Thomas’s view of the Uba river, a tributary of the Irtysh.43

Although Thomas ‘was working on his pictures’, he succumbed to another day’s ‘splendid sport … These shooting parties are very pleasant and the Colonel takes care to have plenty of eating and drinking’.44 When back in Barnaul, General and Madame Anosov called to see his pictures and ‘were both much pleased. The General said I had painted Siberia as it is [and] that there was nature in all My Works and not Fancy.’45 After dining with Colonel Sokolovsky the Atkinsons stayed till midnight for a dance. Then Thomas accepted Sokolovsky’s invitation to a shooting (and sketching) trip about 250 versts east46 to the river Mrassa and the upper Tom, leaving Lucy behind with their friends Colonel and Madame Stroleman, with whom they were staying.47 It was, Lucy points out, Sokolovsky’s annual visit to the goldmines.

The party was rowed down the Ob to a rendezvous with carriages (probably tarantas) and then set off fast48 through ‘thick woods’ for many hours. At one point, finding plants growing higher than the carriage, Thomas got out and found that some measured 10 feet 3 inches high. Sokolovsky believed they had grown very quickly, and, on reaching the next village, established that they had indeed been under snow only five weeks before.49

While they had breakfast, Sokolovsky asked a Cossack why there were so many men about. He was told they were workmen meant to be going to the goldmines but refusing to go. Thomas’s journal (which gives no reason for this refusal) records that Sokolovsky

instantly sent for the Officer commanding the soldiers who said he had tried all he could to induce them to go but without effect. Having drunk our Tea, the Colonel opened the window and asked why they remained at the village. When one Man stepped forward and said they would not go, The Colonel ordred the cossacks to give him 50 strokes with the Rods. In a Moment his trousers were down and the rods at work. After receiving half a dozen he bellowed out he would go. In five Minutes they were all on the Road. Made two good Sketches on the River Tom.50

Thomas leaves his feelings unexpressed.

His journal entries for the Mrassa expedition end: ‘This was a most unpleasant voyage. Six hours of Thunder and heavy rain. The effect of the Lightening on the river was very grand. One Moment a Flash that lighted up everything and the next Thick darkness.’ He resumes only eighteen days later, back in Barnaul, about to set off south on a major expedition, this time with Lucy. They left on 9 July (Lucy confirms) at midday, having sent51 their spare baggage to remain with Sokolovsky, and arranged to meet him in Zmeinogorsk, some 300 versts south. The day was extremely hot and they found the level of the Ob had fallen nearly three feet, but it was nonetheless still very high. It took them almost five hours to cross, and on the other side it was difficult to get their carriage through the deep mud.52

They drove on and woke with the dawn to find they were travelling over what seemed a new country, flat, uninteresting and with very little forest. That afternoon they saw at last a dim outline of the Altai mountains, still very distant, crossed several small rivers, drank tea ‘at a most uncomfortable place at 8 oclock’ and then late that night Thomas found he had lost his shuba or long heavy fur coat (so necessary for winter, ‘the only warm covering we had, and, besides, very expensive’, wrote Lucy). Their Cossack coachman took one of the horses and went back to find it. Hour after hour passed. He at last arrived with the shuba about 5 a.m., having ridden twenty versts and back to find it, ironically, only about two versts from where they were.

At Biisk, their next stop, a small town in the Biya valley, the ispravnik (chief of constabulary) received them very politely and immediately ordered all preparations to be made for their onward journey, which included provision of ‘an interpreter, another Cossack and “vodky for the men”’. Colonel Keil, the officer in charge of the Cossacks, ‘a most gentlemanly man’, Lucy calls him, called on them and invited them to tea.

The police chief entreated them to stay a few hours longer for the ball given in honour of his wife’s name-day. Thomas’s journal records solely that ‘We supped with them and then departed at 11 oclock’, but Lucy, far more interested in people than her husband was, recalls first that her own costume, ‘though exceedingly pretty …, [was] not according to our English notions’.

The material was grey drapes de dame, made short with Turkish ‘continuations’, black leather belt, tight body, buttoned in front, small white collar and white cuffs, grey hat and brown veil: in this costume, minus the hat, I entered the ball-room. Here we found the ladies seated in chairs, stuck close together all round the apartment, and each lady having a plate in her hand filled with cedar nuts,53 which she was occupied in cracking and eating as fast as she could; their mouths were in constant motion, though every eye was turned upon poor me, who would gladly have shrunk into one of the nutshells.

The Atkinsons stood talking with Colonel Keil, and were sorry to see so talented a man, who was possibly of English descent, compelled to associate with the sort of people present.

He said he rarely mixed with them; there were times when he was obliged to attend these gatherings [at Biisk]; that night, on our account, he had been induced to accept the invitation. He continued: ‘Not one single associate have I here, and, if you will come with me, I will show you how rationally they spend their time.…’ We … found the gentlemen at cards, some quarrelling over them, others drinking hard, and, again, others who had already had more than a sufficiency. ‘Drink’, the Colonel said, ‘I cannot; in playing cards, I take no pleasure; so I spend my time with my books, or I go alone to shoot: thus I pass my leisure hours.’

I [Lucy] enquired if the ladies were always as silent as I now found them? ‘Yes; when any of the opposite sex are present, but when alone for a short time, the noise of these men is nothing in comparison with theirs; and now they have a theme which will last for months; that is your visit.’

At 11 the Atkinsons left, anxious to be off, and found the ascent out of the Biya valley difficult. The frequent vivid lightning kept them awake but allowed them to notice the landscape (and Lucy seems to have copied Thomas’s journal here almost word for word):54 for some distance small, round treeless hills overlooking the valley: ‘the scenery … very pretty, particularly at dawn … dark Pine Forrests as far as the Eye could reach with fine bold mountains in the distance’. They arrived at the village of Saidyp, and almost immediately were greeted by a distant thunderstorm in the mountains. Cossack families, the only inhabitants, assured the Atkinsons ‘for our comfort’ that they would meet such storms in the mountains every day.55

They were at last entering the Altai mountain region, and here at Saidyp the travellers had of necessity to leave all inessential items behind. No carriage could penetrate any further, so the journey onward over mountains, through forest and across rivers had to be on horseback. When the horses were ready the women came to see Lucy off, following a short distance to wish her a good journey. ‘One old woman with tears in her eyes had entreated me not to go, no lady had ever attempted the journey before. There were Kalmyk women living beyond but they had never seen them’.56 Earlier that day the same old Cossack woman had offered to let her daughter come on the journey to take care of Lucy: ‘however, when the daughter came in, a healthy, strong girl, some thirty-five summers old, she stoutly refused (to my delight) to move; the mother tried to persuade, and did all she could, it was of no use; and I was left in peace’. Lucy went on:

We now mounted our horses [and this was the beginning of many weeks in the saddle], I riding en cavalier. I must tell you that I took from Moscow with me a beautiful saddle, which I was occupied one day in Barnaoul examining, when Colonel Sokolovsky entered. He demanded what I was going to do with it; my reply was, ‘To ride: I cannot do so without one, and the Kalmuks, I presume, have no such things.’ ‘No!’ said he, sarcastically, ‘and they will be enchanted to see yours; but what will please them most will be the sight of an English lady sprawling on the steppes, or with a broken leg in the mountains. But’, said he, ‘seriously speaking, you cannot go with such a saddle: first, the horses are not accustomed to them; and secondly, in the mountains it is quite out of the question.’ He then offered me one of his own, which I accepted, and left mine until our return; and thankful am I that I did so…. Our horses have stood on many points, where we could see the water boiling and foaming probably 1,000 feet below us; just imagine me on one of these places with a side-saddle!

The party now consisted of the tolmash (interpreter), ‘my [author’s italics] Cossack’ according to Thomas’s journal57 (why not ‘our’? one might ask), five Kalmyks and eleven horses. They reached the river Biya, here broad and deep, and found the grass and plants growing high above their heads even on horseback. Thomas shot several ducks and they caught good fish for their supper, Lucy records:

That night, for the first time in my life, I had to sleep à la belle étoile, with my feet not ten paces from the Bia. First a voilok was spread on the ground, over that two bears’ skins, so that no damp could pass through. I lay down, of course without undressing. The feeling was a strange one; sleeping in a forest, the water rippling at my feet, and surrounded by men alone.58

Next morning they rode off at 6 a.m. and began to climb ‘over high and abrupt mountains, affording fine views of this vast mountain chain’.59 They stopped at a Kalmyk village to ‘dine off most exquisite fish, caught fresh from the stream’, according to Lucy, proceeded with more difficulty and were ferried across another river, the Lebed (or swan). Unusually, ‘Lucy began to flag’, but they needed to reach a second Kalmyk village and did so in the evening, having travelled 65 versts that day, some of it in heavy rain.60

After some ‘good Fish and Fruit’, a balagan was erected for them, so Lucy for one slept better and, by hanging up a sheet at its open side, was able to undress. Thomas ‘had been in the habit of sleeping among these wandering tribes’ without undressing and, telling him she would soon be ‘knocked up’ if she did likewise, she advised him to follow her example, which he began to do to his benefit. In the pavoska she had ‘invariably unfastened every string and button before lying down. How delighted I felt this night to stretch my weary cramped limbs!’ Although Lucy did not feel in the least tired on horseback, the first two or three days when she was helped off her horse she could not stand for several minutes and, determined to conquer this weakness, dismounted on her own, refusing any assistance – and walked, for a moment fearing she would fall. Thereafter she had no more problems.61

The next morning, Lucy had ‘rather a narrow escape’ when they had to ascend some high granite rocks, which the horses found very difficult. Near the summit her horse stumbled and slipped back, placing her in great danger. But she managed to keep her seat, got her horse up ‘and [was] proud enough, I can tell you, to have won the admiration of the Kalmuks, because they are splendid riders’.

After nearly fifty versts, now travelling over high and broken hills covered either by dense pine forest or tall grass and plants, they reached another Kalmyk village where they were given fresh fish and plenty of fruit. They were just ending dinner and about to depart when they saw a young, pretty black-eyed girl running fast towards the Biya,

which, at this point [Lucy writes], runs boiling and foaming at a fearful rate over large stones. There was a look of wild anguish on her face. We then saw a man on horseback galloping after her and a number of others following. The instant she reached the stream, she leaped into the boiling flood; at the same time, tearing off her headdress, she threw it at the man on horseback, and was instantly carried down the river at a frightful speed. A great rush was made to save her; several jumped on horseback and galloped along the banks as hard as they could; when some distance beyond her, one of them sprang into the stream and succeeded in catching hold of her, and with much difficulty brought her ashore.62 [Here she was following closely the words in Thomas’s journal.]

It then emerged that the man following her on horseback was her brother and guardian, come to take her back to their village and force her to marry a rich old man when she was enamoured of a village youth. To avoid this fate she preferred to drown. After a time, however, she began to show signs of recovery, and the Atkinsons started on the day’s long ride. On their return, they descended the Biya by raft so were unable to stop at the village and, says Lucy, never learned the fate of ‘the young damsel so miraculously saved; no one had expected she would be taken out of the water alive’.

Inevitably they were ‘up and off early’ next day with some very difficult passes to negotiate over granite mountains, in places ‘quite perpendicular down to the River. Our Horses stood on many points where we could see the water boiling probably a Thousand feet below us. Lucy rode over these places without quailing in the least’, wrote Thomas proudly.63 Once descended to the river bank they found a good route ahead, the ground covered with bilberries ‘on which we made a glorious feast’, and after a very long ride stopped to dine at another Kalmyk village. Here they came across ‘another curious scene’ (both use the same words): an old woman surrounded by six men and nearby a group of girls round a very pretty girl of sixteen or so, cracking nuts with apparent unconcern. As soon as the Atkinson party appeared the girls came up to Lucy, offering her nuts, and some went off to pick bilberries for her. The pretty girl stayed where she was but kept looking at the men and the old woman, who, it turned out, was her mother. The men, of very different ages, were the girl’s suitors, one of whom, Lucy says, the mother thought ‘a most desirable match’, but the girl wanted none of them.

Thomas was ‘now called upon to decide the case, whereupon he took his seat upon a piece of rock’. The mother and the suitors surrounded him, the Atkinsons’ interpreter by his side. Lucy describes the scene:

Each … [suitor] pleaded his cause with much earnestness and apparently with great eloquence and fervor, but their words seemed to fall upon the ears of the maiden without effect, as she remained immovable.

One … described the impression her beauty had made upon him, another spoke of his rank, a third talked of his skill in the chase, a fourth of his strength … a fifth of the care he would take of her in sickness as in health; but the most eloquent of all was an old man, who became greatly excited in his long speech about his possessions, cultivated land, herds of cattle, and position as the chief of the village, and finally of the great love he bore towards the maiden; how he had watched her day by day from childhood.… The speeches were translated to Mr Atkinson, who … asked her … which of the suitors she preferred … if she were allowed to choose (she said), she should not consent to take any one of them; as none of those present pleased her.

I then suggested’ [Thomas’s journal records] that the girl should remain with her Mother untill some one proposed … more to her wishes this satisfied all parties and our Court broke up.64

They rode on through a pine forest on a day so intensely sultry with not a breath of wind that Lucy two or three times fell asleep – and actually dreamed – on her horse. They stopped for the night at the last possible resting place before their objective, Altin-Kul, the ‘Golden Lake’ (now Lake Teletskoye). This was to be their furthest point east in the Altai, far east of Europe and north indeed of what was then Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). A large balagan was soon prepared for them, covered only with grass as there was no birch bark around, and a good wood fire was made close by. They settled into their bed and woke two hours later with ‘the thunder roaring and the lightning flashing’ (Lucy’s words) and (now Thomas’s words) ‘the Rain pouring down in Torrents [and] our bed and everything drenched. In fact we lay in water without any means of shelter and thus we continued untill daylight’.65

When they rose before dawn it was more like turning out of a vapour bath, thought Lucy. But at least it soon looked like a fine day, and a good fire was made to dry their things. They ‘ordred’ tea as soon as possible and started off at 7. Scarcely a verst from their camp, Thomas’s journal relates,

We found the rocks so high and abrupt that we could not ascend; this compelled us to go round a point jutting into the River which runs at this place over large stones making a great rapid. Round this point was a narrow ledge on which the Horses can go but up to the saddle-flaps in water. The greatest care is required to pass along. Once off the ledge you are in deep water and carried away amongst the Rocks. All past well except Lucy. The Cossack who led her Horse did not keep him close to the rock. In two or three steps he was in deep water and swiming. Our guide saw this and called to the Cossack to hold the Horse fast by the Bridle or they would both be lost. Lucy sat quite still (tho’ the water filled her Boots) and was drawn around the point and landed in Safety. This was truly a most dangerous place. [Lucy’s account here copies Thomas’s journal entry almost word for word.] Our road was now along the Rivers bank for about two versts but now the mountain must be ascended, a work of difficuly and danger still we pushed on tho Slowly.66

The mountainside was indeed so steep in parts that their horses often slipped back – ‘I do not exagerate’, Thomas’s journal records – and, reaching the summit at last,

a splendid view was spread out before us: immediately under our feet ran the River Bia which we could see winding its course among the mountains like a thread of Silver. Looking to the West the Mountains rose far above the Snow line, their Summits beautifully defined against a deep blue sky. The nearest mountains were clothed in beautiful Foliage of a fine warm green shading … into the distance with purple and Blue while the foreground on which we stood was covered with ‘Feather Fern,67 large plants and long grass equalling in Luxuriant [luxuriance] plants grown under a tropical Sun. [Once again, Lucy uses Thomas’s words here almost identically in her book.]

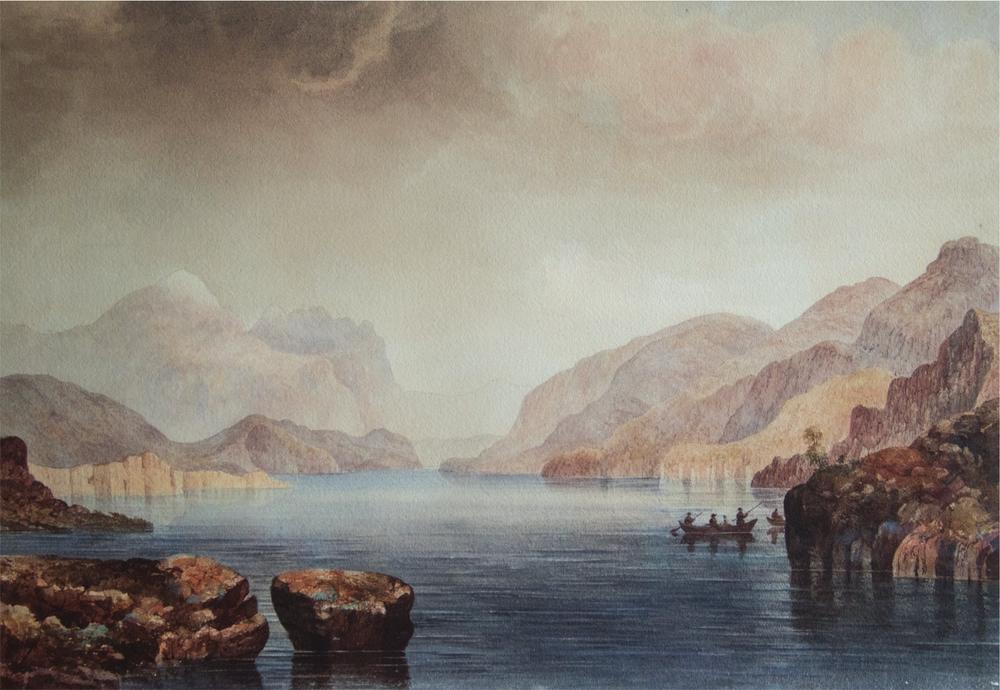

Three hours’ ride took them to the far side of the mountain and the start of a very difficult descent to the Biya, ‘without accident’, which Thomas again underlined in his journal, and after another hour, as the sun was setting, they reached Altin- (or Altyn) Kul, from which the Biya flows. This long and particularly deep lake, known and famed for its beauty and clear water, is set among unspoilt and unpopulated steep forest-clad hillsides down to the water’s edge. Thomas found it ‘one of the Most lovly spots in the world…. We stood looking on this picture for a long time enraptured by its beauty.’

Many Kalmyks gathered to ‘receive’ the Atkinsons – a great curiosity to the locals – and that evening they crossed the lake in a small boat to a Kalmyk aul or encampment of a few wooden houses with birch-bark roofs and a hole in the centre to let out the smoke, with only cooking utensils inside plus one or two boxes for meagre possessions. Lucy was presented with a large bunch of wild onions which the visitors were to find in abundance on the lake’s shores, eaten (along with many other bulbous roots) in large quantities both by Cossacks and Kalmyks.

Thomas was travelling with his flute (of which there has been no mention before in his journal) and half-way back across the lake he began to play several tunes ‘to the great astonishment and delight of our new friends.68 On landing they all came round us and begged … that he would play again.’ According to Lucy:

The power he thus gained over these simple-hearted people by his music was extraordinary. We travelled round the lake in small boats, it was a tour of eleven days, and in all that time he never once lost his influence; like Orpheus, he enchanted all who heard him; without a murmur they obeyed him in everything; indeed, there was often a dispute to ascertain which might do his bidding; and there was no lack of hands to spin the line which was required to sound the lake.

They woke up next morning to what seemed a lovely day ‘rendering the scene even more enchanting than yesterday’ and spent it preparing for their long journey round the lake (approximately 78 km long but only 2.5 km wide). They set off in two canoes fastened together69 ‘having the good wishes of all our new Kalmyk friends for our success and safty’.

‘As we advanced’, wrote Lucy, ‘each turn appeared to open out new beauties to our view’ and Thomas found a good scene for a sketch looking east. He was struck by ‘the fine cedar trees which extends up the mountain to a great hight’ over-topped by precipices of dark grey rock. ‘Looking up the Lake the Mountains vanish off to a great distance shaded from a deep Madder into rich purple and blue, forming altogether a most lovly picture’. Thus the artist.

Having completed my drawing we passed on, but on looking west it was very evident a great Storm was following us. This made us push on as fast as the men could pull that we might find some place to shelter in case the Storm reached us…. The Kalmucks seemed to know what was in store for us [they had warned the Atkinsons that if caught in a storm – frequent on the lake – nothing could save them] and worked hard to reach a little head land formed at the mouth of the first small mountain Torrent. Having rounded the point they ran the boats ashore and hurried us out dragging the boats high out of the water. They then ran with us up to some trees in the hope of affording us shelter. These opperations did not occupy five minutes, but this was even too long to save us a wetting – I … found we were landed on a Mass of Rocks and Earth brought down by the Torrent, on which Cedar Trees of great size were growing. Under one of these we now stood.…

Lake Teletskoye or Altin-Kul (Golden Lake)

This beautiful lake in the Altai mountains, some 57 km long, delighted both Lucy and Thomas, who produced many sketches. They spent several days here being rowed round the lake in canoes by the local Kalmyks. A long description beneath the painting is possibly in his hand.

Turning westward, the Effect was awfully grand. The Clouds where rolling on in black masses covering the craggy summits near us in darkness, while above these white clouds were Rolling and curling like steam from some mighty chaldron. The Thunder was yet distant but the Wind was heard approaching with a noise like the Roaring of the Sea in a great Tempest. On looking down the Lake … the water we had looked upon ten minutes before calm and reflecting everything like a mirror was now one sheet of white foam, driven along like snow. (Had we been caught in this our boats would have gone down instantly).…

The storm appeared at this moment to be concenterated over our heads and made us go, like the Kalmuks, further into the Wood for shelter. Having taken up our station under a large Tree, the Lightening began to descend in thick streams tinging every thing with red. Almost instantly I heard the crash of a large tree struck down not far from us, while the Thunder rolled over our heads in one continued roar. Lucy said ‘I never understood the passage in Byron70 before in which he said “The Thunder dansed.”’ The Storm continued for more than an hour, and then all was calm and Sunny.71

Thomas regarded Altin-Kul’s ‘magnificent scenery’72 as offering him great scope. He made another view looking east where the lake expanded into a fine broad sheet of water with numerous jutting headlands covered primarily with birch and large ‘cedar’ trees, a pleasing contrast to the often sheer slopes leading down to the water.

Every day there were storms on the lake, as the Kalmyks had warned, and to Thomas, ‘the Effect was very fine’. Of one some versts away in the mountains, ‘the Echos amongst the crags and rocks where repeated many times, almost inducing us to believe the Thunder came from Each mountain as it died away in the distance’. But none ever made the same impression on Lucy as that first storm: ‘awfully grand and never to be forgotten’.73

The scenery may have been magnificent, but food was a problem. There were only two poor villages along the lake, although a goat at least was procured from one. Thomas shot some ducks, but game was far from plentiful, and no fish could be had so far. (But this is a very rare discrepancy in their two accounts: as quoted earlier, Thomas found the fish ‘the most delicious’ he had ever tasted.) According to Lucy, necessity compelled them often to eat a species of crow, ‘extremely disagreeable, hunger alone enabling us to eat them’.

Thomas’s journal remains blank for ten days other than a note recording who sat in what boat. But Lucy takes up the tale: when the men reappeared after dark with the goat’s carcass, the cauldrons were soon at work over blazing fires. The Atkinsons went off for a short walk along the shore and, on returning,

one of the wildest scenes I [Lucy] had ever witnessed came into view. Three enormous fires piled high were blazing brightly. Our Kalmuk boatmen and Cossacks were seated around them, the lurid light shone upon their faces and upon the trees above, giving the men the appearance of ferocious savages; in the foreground was our little leafy dwelling, with its fire burning calmly but cheerfully in front of it.74

‘A night scene at our encampment on the Altin-Kul [Lake Teletskoye], Altai Mountains’, 1849

The Atkinsons are in their leafy balagan at one side.

Lucy had learned to shoot quite well, having practised in case of an attack. She was well armed, not only with the small rifle given to her by Mr Tate but also the shotgun presented to her by Astashev, as well as a pair of pistols she kept in her saddle. On one occasion she saw a squirrel in a tree and, having her rifle in her hand, somewhat astonished, shot it as she had never aimed at anything before but inanimate targets. One of the Kalmyks was delighted, patted her on the back, ran to retrieve it and begged her that he could have it for his supper. Lucy, who gained great renown for shooting the squirrel, agreed provided the skin was hers; she wrote that the Kalmyks seemed not to care what they ate and would always consume any lynx which Thomas shot. (But none were mentioned.)

One night on the lakeside the Atkinsons had a visit from some twenty Kalmyks, ‘ferocious-looking fellows’:

seated around the blazing fire, with their arms slipped out of their fur coats … hanging loosely around them, leaving the upper part of their greasy muscular and brawny bodies perfectly naked, and nearly black from exposure to the air and sun, and with pigtails, like those of the Chinese [Kalmyk men shaved their heads completely other than a small section on the crown from which grew a long tuft of hair75], their aspect was most fierce; and still more so, when they all commenced quarrelling about a few ribbons and silks I [Lucy] had given to our men.

The latter had tied red strips from Lucy around their necks, so she gave some to the new arrivals too, thinking how ridiculous it was to see ‘these great strong men’ take delight in such childish pleasures. And yet, she thought, ‘how many men in a civilised country take pride in adorning their persons … and these simple creatures were doing the same, only in a ruder manner!’ Nonethelesss, the quarrelling still continued and Lucy realised they were drunk; only near midnight did the Atkinsons manage to get rid of them.

Ferocious-looking perhaps, but Lucy pitied the Kalmyks for having to pay tribute to both the Chinese and Russian emperors, being so close to the Chinese border. (This system of ‘dual tributaries’ lasted until as late as 1865.76) Lucy also found them ‘extremely good-natured’. Whenever they saw her trying to climb up rocks to pick flowers or fruit, they would climb instead, even in really difficult places. Once when she saw from a boat some ‘china-asters’, Callistephus chinensis, growing in what seemed a totally inaccessible cleft in the rock, a Kalmyk landed from his canoe and clambered up, to Lucy’s great alarm, hanging only on to slender branches growing from the rocks. In addition, whenever Thomas was busy and Lucy went off after flowers or fruit, their Cossack Alexei (whom she writes of as ‘Alexae’ and he as ‘Alexa’), ‘a giant of a man’, always thought it his duty to follow her at a respectful distance and, when unable to go himself, would send a Kalmyk instead.

As they returned to their original starting point around the lake, they experienced their last storm at Altin-Kul. It was ‘grand to look upon – beauty of a different character’, thought Lucy. And here they found (allegedly at last) ‘some most delicious fish, about the size of a herring, only more exquisite in flavour; indeed [wrote Lucy], I never tasted anything to compare with them’. It must have been the same fish that had so enraptured Thomas. Salting a whole barrel, they sent it to Colonel Sokolovsky by a Cossack returning to Barnaul and left the ‘Golden Lake’ with regret; ‘in years to come … how many a pleasant hour we shall pass in recalling to mind these times! Even now, as I glance at the sketches each one has a tale to tell of joy, or dangers escaped’.

II. Zmeinogorsk and the Silver Mines

Since many of the Altai peaks are still unnamed and the Atkinsons seldom mention any names, it is possible to trace their route roughly only by the names of rivers and valleys. However, Thomas, if not Lucy, describes their ascent by horse and then foot up the north side of the 100 km-long Kholzun range (he spells it ‘Cholsun’) which rises to 2,599 m,77 reaching one of its bare granite peaks far beyond the last stunted cedars, having passed a small depression where the horses trampled up to their saddle-flaps on a beautiful bed of aquilegia in full bloom – variegated blue and white, deep purple and purple edged with white. ‘Fortunately’, he writes in his first book, ‘I obtained plenty of ripe seed’ but, frustratingly, he does not tell us why or what he did with it. Nearby was Cypripedum guttatum (Spotted Lady’s Slipper, a species of orchid) with white and pink flowers – which he had already found in the Urals – and also deep red primulae, flowering in large bunches. It is obvious that he obtained his knowledge of geology from those early years as a mason, but where he learned his botany, which he knew far better than Lucy, remains a mystery. However, it was the views that really mattered to him and he considered

The views from this part of the [Altai] chain, (which is not the highest) are very grand. On one side Nature exhibits her most rugged forms, peaks and crags of all shapes rising up far into the clear blue vault of heaven; while on the other, mountain rises above mountain, rising into the distance, until they melt into forms like thin grey clouds on the horizon.

Leaving the mountains, they had a raft made, on which they descended the Biya back to the Cossack village of Saidyp. There the elderly woman, who had begged Lucy not to go to Altin-Kul as no woman had ever attempted the journey before, now discovered that Lucy was planning to go roughly twelve times further, to the Cossack fort of Kopal in the middle of the Kirgiz (now Kazakh) steppes far to the south. Kneeling down before Lucy, she bowed her head to the ground and said, ‘Matooshka moi’ [correctly Matushka moya, ‘My little mother’] (evidently Lucy’s eight years in Russia had taught her conversational Russian but very little Russian grammar), ‘Pardon me, I have a great boon to ask of you.’