THOMAS DIED ON 13 August 1861 (the year Prince Albert also died) from ‘atrophy of the stomach’, atrophic gastritis or chronic inflammation of the stomach’s mucous membrane layer. The funeral was in the little old church in Walmer.1 Thomas was buried in the quiet graveyard, with no stone then or since to mark his passing or his remarkable career. And today it is not known exactly where he lies. Perhaps his was indeed only a pauper’s burial.

Lucy returned to widowhood in London and had the consolation of reading some of the laudatory obituaries of her late husband. The Critic wrote of ‘The great traveller whom we have lately lost’ and the long Times obituary (2 September) noted that:

The story of Atkinson’s life will probably never be precisely told; … but could the biography be written, it would be found one of the most curious and thought-suggesting.… Atkinson displayed in the course of his wanderings great power of endurance, and much address; so that his works have added important particulars to the knowledge of Russia and Asia.… The distances which he occasionally traversed in a single day … were extraordinary; and during the whole of his travels he seems to have never lost a chance of recording what he saw with pencil, colours, and note-book.… No Englishman was better acquainted than he was with the fact of the progress made by the Russians in the direction of India or more competent to give an opinion on [relevant] questions….

He was, declared the Annual Register for 1861, ‘a traveller of much celebrity’ and, starting from

very humble parentage … was entirely self-taught … [and] became a ready draughtsman and a pleasing writer. To these he added a considerable scientific knowledge, and a manner so gentlemanly and winning, that none whom he encountered in his travels or at home could suspect the roughness of the original material. With such singular powers Mr Atkinson was certain to rise….

And in the same vein Joseph Wilkinson, quoted in A History of Cawthorne, p. 215, noted:

If it be a noble thing to add to the stock of human knowledge, Atkinson had gained a high degree of glory. He was in the truest and best sense a self-made man. Those who met him in later years in the drawing-room or country-house, were struck by his undefinable grace and bearing, which are sometimes thought to be the monopoly of ancient race.

The Critic of 14 September under ‘Art and Artists’ devoted about eighteen inches of small-print columns to his architectural career, largely based on The Builder,2 and observed that ‘No man was ever more successful in making friends’. It also noted that he had been reported as dead by an architectural dictionary (see Chapter 8).

The Art-Journal of October should perhaps have the last word. It wrote that

A remarkable man was Mr Atkinson – one whose name will take a high rank among great English travellers…. The difficulties, dangers, and deprivations he encountered on his travels would have deterred a man of less energy and perseverance than himself from proceeding; but he encountered and overcame all, returning eventually to England with a large store of geographical and geological information, and an immense number of valuable water-colour drawings, many of large size,

and his two books ‘form a valuable addition to our standard geographical literature’.

But there were major traumas ahead for Lucy. The first was that, although Thomas left very little money, it was not to come to her. When she applied to the Treasury for a pension apparently due to Thomas3 she ‘was met by the astounding assertion, backed by abundant proof, that she was not legally his wife, inasmuch as he had been married before he went to Russia to a lady who was still living in England’. Why no claim in his lifetime, considering his very public figure? The reason, according to Francis Galton (later Sir Francis Galton, FRS), who was to prove a good friend of Lucy’s,4 was that

no news of him had reached the claimant, who occupied a different grade of society, until a friend of hers told her of his death. This tragic termination affected many of us greatly. We recollected that Atkinson had avoided bringing his wife (as we thought she was) to the forefront, and it had been remarked at the time of the publication of his book of travels that he made the scantiest references to her, and never used the word ‘wife’. It was a wonder, and it is so still, how he dared to settle in London and risk a serious criminal charge [indeed prisonable]. Friends gathered round Mrs Atkinson, as I must still call her, and helped her in many substantial ways.5

In October, letters of administration, in the absence of a will,6 were granted of the ‘effects under £300’ (today, astonishingly, £32,700)7 to the ‘lawful widow and relict’, Rebekah Atkinson of 5 Beaufort Street, Chelsea, where she had been living for ten years in the house of a widow and her children. The previous census ten years before had listed her there as ‘Visitor’, married, aged fifty-four, but the 1861 census now listed her as a boarder further along the street at No. 56, with her occupation given as ‘Private’ which meant, surprisingly, existing on private means. She was listed as ‘Assistant’ to the head of the house, Mary Anne Palmer, ‘Boarding House Keeper’, and Thomas, Lucy and Alatau were all listed in the same census as living in Hawk Cottage only 1.4km away, in a much smaller city than today. Thomas’s estate was to be re-sworn in March 1863 at under £20.

As for her two daughters by Thomas (who had seemingly deserted the family, taking John with him), Martha, the elder, had married a solicitor, James Wheeler – with Thomas indeed as a witness – and had a son and three daughters. Wheeler had become a prosperous railway solicitor to, among others, the Trent Valley railway of which, curiously, Thomas Gooch, present at Thomas’s death and also FRGS, was chief engineer. Emma, the younger sister, remained unmarried and was always to live with Martha.8

How could Thomas have been so deceitful after all he and Lucy had gone through together? He was surely a real romantic, detached from reality and able to shut the matter out of his mind except when he realised it was too risky to mention Lucy and Alatau in either book. The other reason to omit them must have been that travelling with a wife and small child would greatly diminish the intrepidity of his extraordinary story. Did Lucy tacitly accept her – and Alatau’s – omission from both books for that reason? And Thomas also had an odd sense of time: over-conscious of the times of departures and arrivals and the length of journeys, but totally blind to the passage of days or indeed weeks, and – astonishingly – prepared for even more years of Russian travel. He was blind, too, it seems, to questions of money, and how they afforded it all remains a mystery.

It was a double shock for Lucy: bad enough for her to discover that her husband of thirteen years and the father of her child was a bigamist and had never told her after all those years of travel together; and then to find that any money he had would go to the first wife. She was left virtually penniless, and there was no more money to come from either book following the settlement with Blackett, the publisher. And if only half of the Christie’s watercolours had sold, there was little hope there. Fortunately, however, Murchison, now Vice-President (between two of his presidencies of the now Royal Geographical Society), was to be of crucial help to both her and Alatau at this very difficult time. In September, barely a month after Thomas’s death, he began to solicit funds to educate Alatau when he spoke in Manchester at the meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (which he had helped to found). Atkinson’s published volumes, he said, ‘had been received with much approbation by the public, and had been read with much avidity’ and he ‘knew of no traveller that had penetrated where this remarkable man had been’, adding, ‘In his travels he had a spirited wife who accompanied him throughout’ and, as (now) Vice-President of the RGS, he said it was his duty to appeal to the public to establish a fund to educate his son, ‘that fine boy’, ‘born in such a remarkable spot’ and ‘bearing so remarkable a geographical name’ so that he should … ‘prove equal to his father’.9

In the RGS archives there is a long, handwritten list of sixty-five subscriptions dated 20 January 1862 totalling £291 1s 4d to the ‘Atkinson Fund’ for Alatau. Murchison heads the list (almost all are FRGS), with the donation of £20 (£2,231 today) followed by many names of the great and the good including George Bentham, botanist and President of the Linnean Society (and son of Sir Samuel Bentham, brother of the philosopher Jeremy, who had an interesting Russian career himself), Sir William Hooker, director of Kew Gardens, William Fairbairn, the President of the British Association, Francis Galton, John Murray, the leading publisher of the time, Speke, the African explorer (surprisingly, not FRGS), four earls and a duke. In the event, nearly £360 (£40,000-odd today) was raised altogether.

By November 1861 Lucy and presumably Alatau had moved from Hawk Cottage to 9 Lilly Terrace, New Road, Hammersmith (now 71 Goldhawk Road).10 On 11 November she wrote on black-edged paper to the poet and politician Richard Monckton Milnes, later first Baron Houghton, well known in his lifetime for his acts of kindness:11

Pray receive my heartfelt thanks for the kindly interest you have taken in me.… We [Mr Humphrey, her solicitor, and herself] find Mr Wheeler [Rebekah’s son-in-law] has deceived in one thing – he sent a paper to me, demanding in the name of Mrs Rebekah Atkinson that everything should be given up to her – she having taken out Letters of Administration, wheras she had done nothing of the kind….

I earnestly beg of you not to think my husband guilty – he was too good a man to deceive me.

… [Thomas] was the kindest and gentlest of husbands, and the best and tenderest of Fathers. I hope one day to be able to present Alatau to you, and you will then judge what a Father he has been to him – a bad man would not have brought him up as he has done.

I beg of you not to alter the former opinion you had of my husband…. It is cruelty to attack a man when he cannot defend himself….12

But Lucy had finally to accept that the story was true.13 She was, however, very lucky to have had the support of Murchison who appealed on her behalf – countersigned by well-known names of the time – to Palmerston, the Prime Minister.

There was, however, a third trouble awaiting her. The title of his second book may have been foisted upon him by his publishers, but the awful truth is that he never got to the Amur at all, although the frontispiece illustration from one of his watercolours portrays ‘A view on the Amoor west of the Khingan Mountains’. In fact, the Amur begins only at the confluence of two rivers due north of the Khingans. What were his motives for this deception, which fortunately did not come to light till after his death but was to become common knowledge before the century was out?14 It is likely that his rise to fame, thanks to his first book, as well as his rise in society, went to his head and Lucy did not want to dissent. But his main motive may simply have been lack of money and encouragement to write about the Amur as of particular interest at the time. While his first volume is deliberately sparse on dates and the chronology very distorted, we know that the Atkinsons returned from Russia by December 1857, as he was writing then from his publisher’s address in London, and there is no mention of any Amur travel in his journals, all dated.15

And while his first book has a map of their extraordinary Russian travels (admittedly badly drawn), the second has a map of the Russian Empire but no route at all. It is, unhappily, an unsatisfactory sequel to his first book in other ways too: a strange combination of subject matter – material left over from his first book including the long story of the elopement of the young Sultan Suk and his love, whom we have met in the first book, and its tragic end. The Amur and its tributaries are not touched upon till p. 405, with a lengthy topographical and historical description of the area, almost entirely impersonal, and finally a long appendix of the fauna and flora of the Amur region. It is a very interesting area, certainly, and unique as the world’s northernmost monsoon forest, with its distinctive ecosystem, but Thomas’s is a compression (it emerged after his death, fortunately) of the far more detailed scholastic tome compiled after the naturalist, geographer and teacher Richard Maack’s expedition, published in St Petersburg in 1859 under a long title beginning Journey on the Amur.16

Inserted in the London Library’s copy by its former owner J.F. Baddeley (1854–1940), British scholar and author who knew Siberia and the Russian Far East, is his pencilled comment – a very bald statement – that from p. 406 ‘to the end is simply stolen from Maack and then without acknowledgement. Atkinson himself was never near the Amur.’ And the lengthy subtitle is, regrettably, a plain falsehood announcing his ‘adventures among’ seven peoples of the area including the Manchus, Manyangs and Tungus.

Thomas’s ostensibly impressive Appendix consists of five pages of lists in Latin and English starting with the ‘Mammalia in the valley of the Amoor’ divided into Upper, Middle and Lower Amur, followed by birds, trees, shrubs and flowers. Then he proceeds on the same basis as regards the Kirgiz steppe, Alatau, Karatou and Tarbagatai as a separate section (though why should they be listed in a book on the Amur?) and the same for ‘the Trans-Baikal and Siberia’; finally, the ‘Trees, shrubs and flowers found in Siberia and Mongolia’ (omitting mammals and birds), but nowhere fish or insects. But Baddeley has once again pencilled in the first page of the appendix ‘Every word [his underlining] of the Appendix is stolen without acknowledgement from Maack and others.’ Even so, Thomas greatly reduced Maack’s original appendix, and some (uncredited) naturalist knowing English and Russian would have had to translate the original Russian into English – no mean task, and done at some point in 1859/60 (perhaps in only months, by whom, one wonders?).

Maack’s book came with a huge-format companion volume of illustrations, some of which Thomas also plagiarised from the original, although in his preface he does at least concede that: ‘With regards to the illustrations … I have added a few characteristic portraits [of local indigenes], copied from a work recently published by the Russian government’ but with no further citation.17 But it would have cost him nothing to acknowledge Maack, assuming he would have had the latter’s authorisation which might not, of course, have been forthcoming for fifty-odd pages. And of what interest would these long lists have been to the English reader? His avowed intention ‘to produce information for the Geologist, Botanist, Ethnologist’, etc. in the event rests very largely on Maack. It is painful for this author – and perhaps the reader – to end this long account of such an impressive life by including Thomas’s very negative side, but balance demands it.

As for his first book, there must be some doubt about his two chapters on Mongolia, full of personal description and adventure as they are and even incorporating three portraits of sultans. There is no mention of Mongolia (or the Amur) in Lucy’s book or in his journals or list of sketches, and the two relevant lithographs in his first book are of ‘Buryat Mongolia’ north of the Russian border. No journals exist for 1852 or 1853 – perhaps lost – and there was an opportunity between reaching Barnaul in July 1853 and tackling Belukha, but there is nothing to substantiate it and the likelihood of crossing the Chinese Empire’s border into Mongolia was basically dismissed after his death.

Is it, however, so heinous to distort or embellish the truth in a travel narrative? At least two highly regarded modern writers have apparently done so: Patrick Leigh Fermor and Bruce Chatwin. But in Atkinson’s case his impressive reputation in his lifetime and acceptance, both by learned societies and London ‘society’, relied on veracity, and he must be held to account for deliberately deceiving – in part only, however – his public, not to mention (such impertinence!) the Emperor of Russia and the Queen of Great Britain. The temptation was too great for this talented, ambitious and determined self-made man, who had achieved so much against the odds and deserves both criticism and admiration – although only the former for his bigamy.

A classic case of at least alleged deception must be that of William Jameson Reid, who wrote the 499-page Through Unexplored Asia (Boston, 1899) about a journey through Western China/North-Eastern Tibet in 1894 but was rumoured not to have been further than Boston central station. There is also the case of the great Charles Darwin, who deliberately altered the chronology of The Voyage of the Beagle (1839) in the interests of his readers, but advised them accordingly.18

Yet Lucy, delightful as she undoubtedly seems, was not entirely truthful herself when she wrote about Thomas to Palmerston in April 1862 (probably still in an understandably overwrought state), ‘for fourteen months before his decease [i.e. from June 1860] he was incapable of undertaking any kind of occupation whatever; [true perhaps, but she omits his one trip at least to the north in the autumn of 1860] owing to illness brought on from overworking himself and taxing his strength beyond its endurance’.

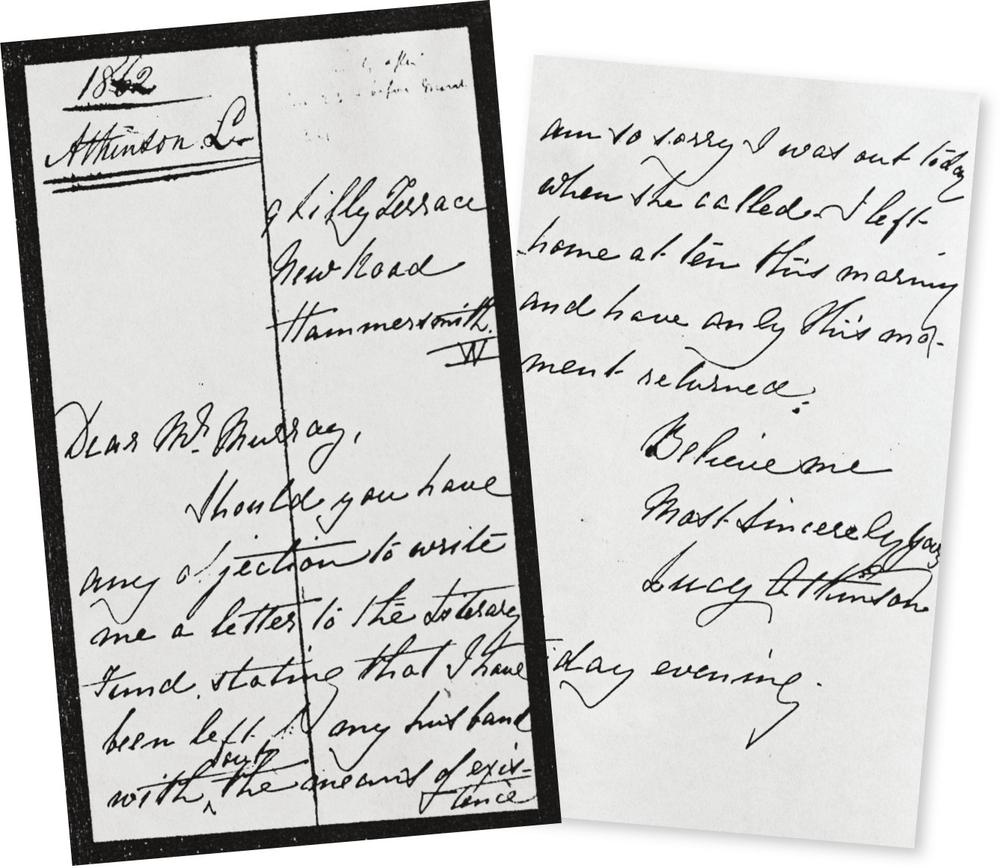

Letter from the widowed Lucy Atkinson to John Murray, her prospective publisher.

She had started to write her own travel account before Thomas died and was advised by the publisher John Murray to write it as a series of letters to a friend. Five months after Thomas’s death19 she wrote, still on mourning writing paper, to Murray, thanking him for his ‘kind encouragement’

to proceed with my simple story, when I have quite concluded it – if it does not please you why there is no harm done – understand. I do not mind trouble, if by writing it over fi fty times I could at length succeed, I would most willingly do so – pray do not hesitate in telling me what you disapprove.

To speak frankly your letter lay some short time on my table ere I dared to open it to know my fate.

In the style I have sent you I can write more letters, equally if not more interesting I so feared you would say they were trash.20

Two months later Lucy applied in her penury as ‘a Widow’ for relief to the Royal Literary Fund,21 citing her late husband’s profession as ‘Architect, Artist & Author’ with the titles of his two books and inserting ‘one son aged thirteen’. She would not have applied, she wrote, but for the death of her husband, due to which

I am left with an only son, totally unprovided for, he [Thomas] having expended the whole of his own means during his researches, in Siberia, Mongolia & Chinese Tatary … after our marriage in Moscow in 1848 – I accompanied him over a period of six years. It was during our wanderings in Chinese Tatary that our only son was born under peculiarly difficult and trying circumstances.

This journey was performed without the aid of any society whatsoever and entirely at his own cost [questionable].

I am now reduced to the necessity of disposing of my wardrobe and a few little valuables I possessed, for our maintenance … [but it is interesting, if understandable, that she did not sell either ring from the Tsar].

And moreover, I may add, even before my husband’s death, we had commenced doing so – always hoping he might recover and be able to resume his labours.22

Strong letters of support were written the very next day or the day after, inter alia from John Murray (whom Lucy, ‘a very exemplary woman’, had requested would make known to the Fund’s Committee her ‘extremely destitute condition … left without any means of support’), Galton, Spottiswoode, Lord de Grey and Ripon, the former President of the Royal Geographical Society and ‘personally acquainted’ with Lucy’s ‘sad circumstances’, and Murchison, who had ‘taken the deepest interest in her welfare’ and enclosed an appeal to ‘Geographers & Men of science and Letters for the purpose of educating her only son born in Chinese Tartary’. These were supported by a copy of Lucy’s marriage certificate to ‘a widower’.

In his letter (of 28 February) to the Royal Literary Fund Galton wrote:

She was her husband’s devoted companion and helpmate in all his Asiatic wanderings (which I need not dwell upon here as they are well known to the Public.) She was, I can testify from direct personal knowledge, the supporter and Encourager of his artistic & literary labour. And she is now by his premature death, – I say premature for he was planning new journeys – as an artist-traveller when his illness commenced, – reduced to the greatest financial Embarrassment.

The education of her boy is indeed provided for, by means of a subscription raised for that purpose but her own fortunes are in immediate need of support.

He had, he continued, known Lucy and Thomas ‘with, I may almost say, intimacy, for the last two years. I sincerely esteemed them both and believe her eminently deserving of a donation from the Literary Fund.’

On 17 March Lucy wrote to the Fund with ‘sincere and heartfelt thanks’ for the £80 ‘so liberally afforded me’, a sum (now worth almost £9,000) which ‘will enable me, I trust, to carry out my project of giving to the world an account of my wanderings in the distant regions of Chinese Tatary &tc where, not only no European, but not even a Siberian [i.e. Russian] Lady, ever set her foot before’. And a few days later she wrote to John Murray again, thanking him for his letter to the committee: ‘£80 … is a great assistance to me’, asking if she should send the incomplete manuscript or wait till it was finished, and presuming she was ‘doing right in taking up the journey exactly as we made it’. She sends her ‘kindest regards to Mrs Murray and yourself’, an indication of personal friendship.

Lucy was fortunate in her supporters, particularly Murchison, and through him the Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society. In late March, a ‘Memorial in favour of Mrs Lucy Atkinson’ was drawn up, addressed to the Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, earnestly recommending the grant of a small pension by the Crown. It attracted fourteen distinguished signatories, headed by Murchison, and including the Arctic explorer (and accomplished watercolourist) Admiral Sir George Back, the Assyriologist Henry Rawlinson, later baronet and President first of the RGS, then the Royal Asiatic Society, peers of the realm, and the President of the Royal Society, General Sir Edward Sabine. The Memorial explained Lucy’s travels with her late husband including ‘the countries of the Kirghis Hordes, into which no Englishman had ever before penetrated’, mentioning his well-known works

descriptive of these regions … justly appreciated by the public, whilst his paintings have obtained considerable praise for their graphic descriptions of the wildest scenes.

Owing to the heavy expenses attending his travels, Mr Atkinson died in poverty, and left no provision for his Widow and her only Son, now 13 years of age….

And, it continued, certain geographers,

who value the labours of Mr Atkinson, have, indeed, subscribed £300 [nearly £34,000 today] … for the education of this fine boy … however, the Widow is left destitute, and we therefore sign this Appeal in the persuasion that, as the relict of an original explorer, who, expending his own means in the extension of Geographical Sciences, was also a popular writer and a skilful artist. Mrs Atkinson comes, we think, legitimately within the scope of the Royal Grant, which has often been assigned to the Widows of persons of distinction in Science, Letters, and Art.23

Meanwhile on 7 April the anxious Lucy sent a direct appeal herself to Palmerston, soliciting a small pension in view of

the benefit my husband has done to Society at large, in bringing back and giving to them in pen and pencil his experiences of countries, for the most part totally unvisited by Europeans.… I should not have applied to Your Lordship, had we not by his death, been left totally unprovided for, he having spent the whole of his own means in prosecuting his researches in the before named regions. The journey having been performed at his own cost, without the aid of anyone or any society whatever [perhaps].

Hoping Your Lordship will pardon my addressing you.

I beg to remain

My Lord

Yours Obediently

Lucy Atkinson24

Then Murchison wrote a six-page letter to the Prime Minister, whom he knew and to whom he had already spoken about the matter, enclosing the Memorial. He explained that, when Atkinson was in Moscow (sic) in 1847 en route to Siberia, ‘he fell in love with the lady … then a Governess’ to the Muravyov family. After a year away, he returned ‘to claim his promise’, and the two were married by an English clergyman, a marriage which produced one son. He describes Atkinson as ‘one of those resolute Englishmen who to the honour of our country rose from the humblest beginnings to distinction’, and his widow ‘the companion of these most arduous explorations which have brought to our acquaintance vast unknown regions’. He goes on to assure Palmerston that

poor Atkinson never received a farthing from the Government or the Czar. He travelled at his own expense – exhausting thereby all the savings of a previous life as an architect and artist in the full persuasion that his paintings and sketches of the wild countries would bring such prices in England which would entirely repay him.

Alas! He was miserably deceived. Few people care to give money for the representation of scenes which they can never visit and the unfortunate traveller reportedly collapsed and died during your first residence there.25

The only advantage to him in Russia (and I had the same) was an Imperial order to travel whithersoever he pleased [not really so in Atkinson’s case].

Pray take this good case into your favourable consideration, for I am sure that it stands on as strong grounds as most of those cases of former grants of pensions from the Crown.

On 26 May, Lucy, understandably still overwrought, wrote a poignant letter to Lord Ashburton, at that time President of the RGS:

All my husband’s property I have delivered over to the principal creditor, but as I fear there will not arise sufficient funds to liquidate the debts, I am endeavouring with my feeble efforts to make the wherewithal to do so, and if I am successful it will be the proudest day of my existence.

Should this man be able to prove (which I doubt) that the first wife is living still I look upon myself as the one entitled to pay my husband’s debts and clear his memory. In the sight of God I am his wife and I have to the best of my ability acted the part of one to him. I never deserted him for an instant either in sickness or in poverty, and I have followed him through dangers which many a man would have shuddered to encounter, and he has ever been to me a good husband during a period of fourteen years that I have been married to him.

I am sorry to trouble your Lordship on matters of not the slightest importance to you, but I have been obliged to say so much on my own behalf as Mr Wheeler has written to all the principal persons at the Geographical [nothing now in their archives], and though not in direct terms still has worded his communications in many instances as to lead them to conclude I had been living in an improper way with Mr Atkinson, having done so, it is just possible he may have written to your Lordship.

The way Mr Wheeler has attacked my character is the more despicable and cowardly as I told him when he (my husband) had married me. The manly way would have been to attack the culprit if such there was, and not the poor victim.

A month later Lucy wrote again to Murray, her prospective publisher, exhorting him not to think she had been spending her time idly:

Since I saw you I have had a good deal of trouble and anxiety – that is over for the present, and whatever comes in future, I trust it will not produce the same effect upon me. I tried hard, very hard to collect my thoughts to write, but I could not do much, and threw my pen down in despair. Last Monday I resumed it, and I hope nothing more will come to interrupt me for a while….

I do not know if my feeble efforts will be of any use. I deeply regret not having the assistance I had hoped to have had – then my letters would have been very different. I could have said more, but fear not to be quite correct, and as this is not fiction it is better to write only of what I am quite sure…

With kindest regards to Mrs Murray and yourself.26

Lucy’s efforts were anything but feeble. Recollections of Tartar Steppes and their Inhabitants, which came out in 1863, is a lively (and badly neglected) gem of Victorian women’s travel, half the length of her husband’s first book, and without a trace of rancour; it has, mercifully, a table of dates of their travels as well as four engravings, possibly from her husband’s watercolours, and is a delight to read, full of excellent – and often amusing – anecdotes. She emerges as tough, spirited, humorous, independent and resourceful, and a good shot and horsewoman as well as a caring wife and mother – the real hero of the story. Murray’s formula of writing it as a series of letters worked extremely well.

The reviews were, rightly, very positive. The Westminster and Foreign Quarterly Review (1 July 1863, 254–5) considered that ‘Mr Atkinson was singularly fortunate in the companion he chose for his wanderings; few ladies can tell a more adventurous tale and still fewer could have exhibited such courage and powers of endurance … to travel 7,000 miles in a single year, and for the most part en cavalier … is a feat of which any lady may be proud.… Altogether this volume can have few competitors, either in novelty of subject or interest of detail, while it is written in a cheerful and animated way that gives it an additional charm.’ And The Literary Gazette (14 March 1863), which mentioned the untimely loss of her husband ‘to be deplored by … [interestingly] thousands’, wrote that the adventures and exploits that she shared ‘throw into shade the most daring undertakings of all previous lady travellers’.

The Athenaeum27 in its seven-column review quotes and pontificates at some length but does not really review the book at all. Interestingly, it cites her Christian name, which she kept off the title page, credited only as ‘Mrs Atkinson’. Professor Anthony Cross, well known for his work on past Anglo-Russian relations, wrote a nine-page introduction to a new impression of Lucy’s book in 1972,28 in which he observed that her ‘account of meetings with survivors of the Decembrist uprising … has long been of interest and importance for [particularly Russian] historians’ and that she writes ‘with unassuming modesty and the ring of truth’.29

Following in her husband’s footsteps, Lucy presented the RGS with a copy of her book, inscribed on the flyleaf: ‘The Geographical Society from the Authoress [perhaps to avoid using her Christian name]. March 2nd, 1863’. And presumably for that reason the title page is inscribed simply ‘Mrs Atkinson’. In May Palmerston’s private secretary wrote to Murchison30 informing him that Lucy had been allotted a Civil List pension of £100 a year, which would have very greatly pleased her, as much as the success of her book.

Lucy can hardly have sent out many free books, but we know she sent a copy of her ‘little volume’ to one supporter, the first Baron Houghton (formerly Richard Monckton Milnes), which, modestly, she did ‘not pretend to think’ would interest him, ‘but it probably may the ladies of your family: if so I should feel happy to have contributed to their gratification’.31

There is an interesting (undated) vignette of Lucy when she had regained her composure, ‘a bright-eyed, intelligent woman, small in stature’, penned by Sir William Hardman, FRGS,32 who sat next to this ‘very remarkable lady’ at a dinner party (date unknown). Fortunately, she was still persona grata socially. He was impressed that she had given birth ‘lying on skins on the bare ground’. She would rather, she said, ‘be attended in sickness by men rather than women; they make far kinder and more attentive nurses’, and ‘the way in which the Cossacks nursed and played with her baby was strange to see’. She loved Russians, she said, and hated Poles when in insurrection, referring to the Polish uprising against Russian rule of 1863 (doubtless conscious that her previous employer General Muravyov had been sent to put it down).33

The novelist George Meredith was a fellow guest on that occasion, ‘in high spirits and talking fast and loud’, and claimed that the view from Surrey’s Hindhead was very like Africa. ‘Mrs Atkinson pricked up her ears, and bending forward across the table asked in a clear but low voice, “And pray, Sir, may I ask what part of Africa you have visited?” Poor Meredith; he had never been further south than Venice!’ But ‘No one could be more amused at his own discomfiture than he was himself.’

Later, the talk was of some cannibals who were to visit Britain as a ‘sensation exhibition’, and the question of feeding them arose. ‘“Oh!” says Meredith, “there will be no difficulty about that, we shall feed them on the disagreeable people, and those we don’t like.”’ Hardman, who tells the story, was amused at the notion and, turning to Lucy, said, ‘I wonder how many persons would survive if every one disposed in that fashion of those he did not like!’ ‘“Yes, indeed”, she replied, “there would be very few, if any, and that gentleman (meaning Meredith) would be one of the first to go!” Conceive my amusement, picture to yourself the chaff, the laughter, when I reported this to Meredith! We all liked the little woman immensely, and mean to improve the acquaintance.’ But unfortunately, there is no record of this happening.

Alatau, meanwhile, was sent to Rugby School thanks to the subscription of nearly £300 (today nearly £33,000)34 raised by Murchison and, primarily, other Fellows of the RGS.35 Possibly having been taught by Lucy on his own, he must have found it a life-change to attend a Victorian English public school; he was inevitably teased for his outlandish names, and a couplet went the rounds:

Alatau Tamchiboulac

Rode about on an elephant’s back.

Lucy’s widowed mother and four youngest siblings36 had emigrated to New South Wales, joining three already there, leaving Lucy with a brother and sister in England of whom we know nothing. It is thought that Lucy may have returned to Russia, probably to see her old charge, Sofia, now married with her own children.

In July 1869, seven years after Thomas’s death, writing from ‘4 Paragon, New Kent Road’ in the East End to Murchison, she writes to say how grateful she is ‘for the pains you have taken to draw up the appeal to the Premier [evidently for a pension]’. And she adds: ‘Trusting that Mr Gladstone [then Prime Minister] will be pleased to look upon it favourably.’37

And in December she writes after receiving news from Murchison of a £50 pension (some £5,800 today),38 ‘In consideration of her services to literature’39 writing now from the Grand Hotel Royal, Nice, Alpes Maritimes, where she was probably the companion to some well-off English lady:

How I am to thank you I hardly know – no language I would use would ever show how deeply grateful I am – your generous aid enables me to feel easy about my old age. I now know when the time arrives for me to give up my previous employment [unknown] I shall not be an outcast and I am sure your own kind heart must feel as gratified in having secured to me the grant of a Pension as I felt rejoiced at obtaining it.

Alatau Tamchiboulac Atkinson in his maturity.

She does not feature in the 1871 census; perhaps she was in Russia. But the 1881 census tells us that Lucy had moved to 43 Mecklenburgh Square (in Bloomsbury, today perhaps the best preserved of all London’s Georgian squares), the home of her cousin Benjamin Coulson Robinson, a retired ‘Serjeant-at-Law’,40 his wife, Hannah, and his aunt, Maria. Lucy was probably acting as housekeeper (and poor relation). Thomas had proposed Robinson for membership of the RGS in 1860 and the latter had donated generously to Alatau’s education.41 A year after Robinson’s death in 1890, Lucy was a visitor42 ‘living on own means’ (a relief!) maybe quasi-permanently in the house of Robinson’s sister Sarah and her husband Thomas Weatherall Sampson, a prosperous ship-broker living at 376 Camden Road, Holloway, further north and not so grand.

Lucy and Rebekah probably never met. Rebekah died on 7 May 1872 from paralysis, aged seventy-seven, according to her death certificate.43 Despite the rigours of her travels, Lucy was to live on until 13 November 1893, thirty-two years after Thomas’s death, dying at the age of seventy-six from acute bronchitis, oddly enough at 45 Mecklenburgh Square, two doors away from her old residence at 43, rather than Camden Road, her more recent home. By her will she appointed Alatau as sole executor, left her daughter-in-law Annie, ‘the wife of my dear and only son’, £100 with £100 legacies totalling £900 to her grandchildren, and the residue to Alatau. In due course her estate was proved, surprisingly, at £3,071 5s 9d, equivalent to at least £360,000 today. Where could the money have come from? Sampson died the same year as Lucy, leaving over £50,000 (now £5.98 million), so perhaps Lucy benefited from his fortune.

She was buried in Tower Hamlets cemetery, Stepney, in London’s East End, joining her father there as well as Benjamin Coulson Robinson. Unlike Thomas, she has a gravestone, paid for by Alatau, that commemorates the last resting place of this remarkable and thoroughly admirable woman.44 The inscription is in bad condition today but it is possible to make out:

Sacred

to the memory of

Lucy Sherrard Atkinson

widow of

Thomas Witlam Atkinson, FRGS, FGS

Born April 16th 1819

Died November 3rd 1893.

We have loved thee with an everlasting love,

Therefore to divine kindness were drawn thee.45

As for Alatau, he was to have an interesting and successful career – surprisingly in Hawaii. He resolved to teach after Rugby, following in his maternal grandfather’s footsteps. After attending a training course in the North of England, he taught for two years at Durham Grammar School (Murchison’s alma mater, another good deed) and in 1868 married Annie Elizabeth Humble, daughter of an artist. Their first child – christened ‘Zoe’ (after an earlier love, the Italian Zoe Giovanetti, who became her godmother) and also ‘Lucy Sherrard’, a token of Alatau’s feelings for his mother – was born at the end of the year, when he sailed with wife and new-born child for the Sandwich (now the Hawaiian) Islands.

Alatau and his family outside their house in Hawaii.

He established his own school, St Alban’s College, which he ran for many years before becoming principal of the famous old Fort Street School. In addition, he set up a free school system open to all races, insisting on English as the taught language in these multi-ethnic islands in mid-Pacific, always with a vision of Hawaii’s future, leaving many prominent men of Hawaii in ‘heavy debt to the distinguished educator’, not just in schools but via the press and platform. He also began reformatory schools for juvenile offenders, became Inspector General of Hawaii’s schools, which he reorganised, frequently visiting all the islands, and then moved on to journalism, becoming editor of the Hawaiian Gazette and then Hawaiian Star, as such largely shaping public opinion in favour of American annexation (1898), on which he was determined. He twice administered an official population census of the islands, produced significant papers on education, and produced satirical verse and cartoons: an astonishing career after such an extraordinary start!

Although Lucy never saw Alatau again, she kept very much in touch (no letters survive, although she wrote to Murchison after her son’s arrival in Hawaii that he was ‘enchanted with the island and its climate – his school was doing very well’).

He and his family – his wife Annie, three sons and four daughters – lived in a comfortable two-storeyed house with verandas on all sides and had a beach hut on Waikiki. Despite his high-profile career, he was never well off with so many children to bring up and may have sometimes taken in lodgers; one daughter thoughtfully eloped to save her father the cost – and debt – of a formal wedding. Zoe, the eldest, married R.C.L. Perkins, an Englishman who collected insects, birds and snails in Hawaii for the Royal Society, which resulted in the first comprehensive work on the islands’ fauna, a three-volume Fauna Hawaiienses. One son, also Alatau, ended as acting governor in 1903. Another son, Robert, and his wife, entertained the Prince of Wales, later Edward VIII, and his party when in the Pacific in 1920 at a traditional poi supper at their home.

Alatau died in Honolulu suddenly on 24 April 1906, aged fifty-eight. Hawaiian obituaries speak of his warmth, good-natured enthusiasm and his comradeship and loyalty to associates: ‘enthusiastically fond of Hawaii’, he believed in its great future, and to it he devoted a capacity for decision, ‘rare executive ability’, ‘great talents, an indomitable energy and enthusiasm that never failed or altered [shades of his father], and a luminous zeal’,46 while a 1925 history of Hawaii described him as ‘one of the most brilliant and widely loved men of his period … his strong personality left a marked impression upon … [its] cultural life’.47 He is the one real-life figure to enter the pages of James Michener’s best-selling novel Hawaii, where he writes: ‘the characters … are imaginary – except that the English school-teacher Uliassutai Karakoram Blake is founded upon a historical person who accomplished much in Hawaii’. And one road commemorates Alatau today: Atkinson Drive in the centre of Honolulu.