It’s the middle of Holy Week. Three days ago Jesus rode into Jerusalem on his donkey. The day after tomorrow they will be nailing him to his cross. Today the table is being booked for the Last Supper, and I’m standing in a field pulling up a broad bean plant, putting it into a plastic bag and putting the bag into my jacket pocket.

The remit for this piece was vague but simple: did I want to write about things in London disappearing?

‘How many words?’

‘However many you want.’

‘OK. When do you need it for?’

I can’t remember the answer to that but today I’m attempting to fulfil my side of the deal.

The trouble is, I don’t really give a shit about London. Never lived there. Wouldn’t mind if the whole lot disappeared in front of my eyes and we were left with a huge wild forest at the heart of south-east England with red squirrels leaping from tree to tree, clean-running chalk streams, wild deer roaming the glades – all that sort of stuff. And I certainly wouldn’t mind if it was this that I would be strolling through for the next couple of days, after I get myself out of this bean field, instead of trudging over very ungolden pavements for the next however many hours it’s going to take me.

For that’s what I’m going to be doing. All my life it has been ‘if in doubt, go for a walk’. The bigger the doubt, the bigger the walk. At some point I started to try to justify these walks, aggrandize them, anoint them with meaning, when in fact they are just me getting out of the house away from any number of responsibilities, to give myself time to mull things over. Then there is my fixation with maps. It was when I was a teenager that I started to draw lines across them and follow the lines on foot. Sometimes the line went around in a circle, sometimes they squiggled and sometimes they were just regular straight ones. I have written about this bent at length elsewhere. The line that I am going to be following for the next couple of days is a straight one, across London from north to south, passing through Charing Cross Station at the Queen Eleanor Cross.

At school we were taught something about Queen Eleanor’s crosses. She was the wife of one of England’s medieval kings and when she died, somewhere up-country, she was taken to London to be buried. After she was buried the king commissioned these elaborate monuments to be sculpted and positioned at the various points along the route where her body had lain for the night. One of these places was called Brigstock in Northamptonshire. This village was only a few miles from Corby, where I spent my secondary school years. I used to pass this Queen Eleanor Cross when I took the bus to Kettering. It held a romantic place in my imagination.

The teacher also told us that the last Queen Eleanor’s Cross is outside Charing Cross Station and that this point is considered to be the centre of London, rather than Buckingham Palace or Westminster or Piccadilly Circus or any of the other more famous landmarks. It was one of those useless facts that has stayed with me down through the decades when all the ones that would have come in handy have departed my memory.

Yesterday I tried to buy the two Land Ranger Ordnance Survey maps that cover London. The shop I was in had only one of them, Sheet 177, which covers East London. Luckily for me, Charing Cross Station just made it on to the page, about a quarter of an inch from the left-hand edge. I got my rule out and drew a line which followed the longitude that would cut through Charing Cross.

I’m standing on that line in this bean field, right now. It’s the line that I’m going to follow on my feet for the next couple of days. What I imagine I will be doing with this walk across London is slicing the capital in two. Symbolically speaking, anyway. Like slicing an apple or an onion in two so you can see the inside. That way I can have a better look at it. See what’s rotting, see how far the worm has got, count its rings and thoroughly mix my fruit and vegetable metaphors before I reach the end of this paragraph.

The idea was that I would start my walk in the first bit of proper open country at the top of London. And when I say open country I don’t mean parkland or golf courses and definitely not paddocks used by riding stables. Proper open country that farmers use to make a living growing crops or with sheep or cows in. Proper farmers who hate people from towns ’cause they don’t understand their ways. Farmers who support the Countryside Alliance and all that sort of stuff.

As for the disappearing London bit, I didn’t have a clue. So I asked friend, colleague and film-maker Gimpo to come along with me with his camera. Among other things Gimpo is a good walking companion and we both need to get in shape for our forthcoming walk across Iceland.

I had this half-baked idea that on our walk south across London Gimpo would film cars, buses, taxis, lorries, motorbikes, rickshaws and any other form of transport driving around corners. Then we would have a short film of vehicles disappearing from view, one after the other from the top of London to the bottom. I can’t say that the idea for this film fills me with any sort of great creative enthusiasm. It’s not something that is going to set a new benchmark in the art-film genre, let alone change the face of art history, but it’s what we are going to do.

Gimpo gets out his camera and takes a 180-degree shot of the rural landscape to the north of where we are standing. Then we head for the barbed-wire fence and hedge we clambered over earlier.

Ten minutes later we are well into our stride down the pre-war suburban streets of an area of London my mapreliably informs me is called Oakwood. It’s Janet and John country. I could get cynical about these streets and all they represent: a white, safe, backward-looking England. But I won’t because there are golden daffodils everywhere trumpeting the coming of spring, cherry blossom is already out, the streets are empty of people and moving vehicles. Gimpo and I stride on down the middle of this, following my detailed and meticulously planned route down the hill and up into Southgate. All virgin territory as far as I’m concerned. Down the hill towards Broomfield Park, up Powys Lane and Brownlow Road to Bounds Green tube station, then on to Bounds Green Road.

That’s where I’m standing now, staring at the pavement. It’s not flagstones but tarmacadam. I’m staring at all the ring-pulls from cans of drink which have become embedded into it. Dozens of them. I take a few more paces. No, it’s hundreds of them. I’ve always enjoyed the patina of spat-out chewing gum that decorates our pavements, but this is the first time I’ve seen a similar pattern created by ring-pulls. Then it hits me. Not only do I not give a fuck about disappearing London, I’m interested only in what I haven’t seen before, the new things, what’s going to happen next, what’s appearing now. And what’s appearing now is ring-pulls embedded in the pavement. I look up. Above is a horse chestnut, its large sticky buds are within a week of bursting. Within a few weeks their candles will all be out on display. I don’t give a shit about the past, not now spring is here anyway. All that seeking out the traces of what’s gone before. Give me the new, the this year, the way it’s gonna be. I was going to say the new order but that smacks of Germany in the late 1930s and that’s the past.

I don’t let on to Gimpo how I’m feeling. He’s diligently filming every car that is disappearing around a corner as we tack our way south across the map.

We keep going. Alexandra Palace looms then disappears, then Wood Green where Turnaround Books who distribute a good chunk of the underground and suspect books in the country is based. We pass a school where Gimpo reckons his girlfriend teaches. It might pepthis text upif I could be documenting some banter between the two of us. Stuff that might make you smirk, even disgust you. But no, Gimpo and I trudge on mainly in silence. This is partly because Gimpo is still in recovery from his annual 25-hour M25 spin and all the attendant intake of stimulants which goes with this pilgrimage of his to nowhere.

More and more celandines and dandelions. They are now beaming their golden smiles at me from the most trashed and unkempt gardens. That’s what I like about spring, however much we trash things, you just can’t stopit. Mind you, there are not that many birds about. I’m sure you’ve heard on the radio or read in your newspapers about the dwindling sparrow population. In the couple of hours that have passed from standing in that bean field to lurching down Middle Lane into Crouch End, I’ve not heard the friendly chirrup of a single sparrow.

We are getting into familiar territory. I know these streets well. Crouch End looks very desirable to the upwardly mobile arty type who wants to hold on to something of their supposed bohemian roots. We nearly moved here ourselves a few years back but the house sale fell through.

Gimpo and I stop off at a café to rest our legs and quench our thirsts. It’s all laptops and shaved heads. This may not be the quintessential suburbia of Oakwood where we started but it’s suburbia still, with affectations of hipness.

I want to carry out a survey of the other clients of this café. I want to ask them what they think is disappearing from London right now, what is disappearing this very moment as we sip our espressos and freshly squeezed orange juices. Not what has disappeared since their childhood. That would be too easy, all that eel pie shop sense of community stuff. Is there a sparrow out there in a Crouch End garden thinking ‘Fuck it! I’ve had enough with all the wogs and Pakis. I’m moving to Milton Keynes.’ Are sparrows racist? Am I allowed to use words like ‘wogs’ or ‘Pakis’ in a book like this?

The trouble is I’ve not got the front to carry out my survey and I’m more concerned with a blister coming upon the heel of my right foot. Gimpo sups the dregs of his coffee granules, I drain my freshly squeezed orange juice and we head back out. To carry on with our mission to slice London in two.

Up and over Crouch Hill we get our first panoramic view of London. The day is a good one for walking, dry with a light breeze. But there is a hint of mist in the air which stops the panoramic view from delivering all that it could do on a clear day. The only major landmark that we can make out is the Gherkin. I don’t know what I feel about this building. Theoretically I should love it. It’s new, it’s of a design I’ve never seen before. But something stops me wanting to embrace it in the way I’ve instinctively embraced all Modernist architecture since I first saw a documentary on TV in the mid 1960s about Brasilia. I suppose some building or other must have been made to disappear to make way for the Gherkin. I have always had an urge to flatten whatever house I have been living in and build a Modernist eyesore in its place, the more glass the better. I can’t believe I have ended upliving in a timber-framed house that was built in the 1500s.

Just noticed that while we are surveying the city spread out before us we are standing on a railway bridge. I love to look over railway bridges at the lines below. We all do, don’t we? Even if we don’t want to lob bricks over the side into the windshields of oncoming trains. I look over. No oncoming train, no glistening lines, no rail lines whatsoever. It’s all overgrown, brambles, feral sycamores and a path where once the glistening track was. They must have disappeared when Beeching did his thing. I check the map: this is the Parkland Walk. I wonder if there are any racist sparrows down there planning to move to Milton Keynes. In the mid 1980s I briefly worked with a rock band who came from the far east end, the bit that’s over the border in Essex. They and their families felt the need to keepmoving further and further out of London to stay clear of the onward march of those who are not us. I never had what it took to confront their blatant racism. Mind you, it is always so much easier to be aware of racism in others than what you have got knocking around in your own head. Is racism hardwired? A survival instinct or just a learned thing? Do Darwin or his finches know the answer to these questions? They were a great band. They never made it.

We move on down into Upper Holloway, edge around Tufnell Park, into Holloway proper and past the prison down into Kentish Town. This is all proper urban multicultural stuff, proper London. Graffiti, bendy buses, marauding gangs of school kids, Asian-owned mini-markets with a few hundredweight of fresh fruit and vegetables all polished and stacked upin boxes outside the shopfront, bill-boards for mobile-phone network providers, discarded B&H cartons and empty Sunny Delight bottles roaming free. This is the way inner cities should be. Sod what they were like when you were a kid, this is the way they are today. And I like it. But that’s easy for me to say, I’ve never lived the inner-city multicultural thing. I’ve only lived in (almost) all-white communities. Even in Liverpool it was all white, unreconstructed working class as far as the eye could see. It’s easy for me to be a left-leaning liberal when I’ve never had to watch where I live completely and utterly change culturally within my own lifetime. To feel everything I hold true slipaway for ever. Easy for me to say ‘Well, we live in a country that grew rich out of going wherever the fuck we wanted in the world not giving a toss for the native cultures as long as they learned English, read the Bible and bought our stuff.’ We were the biggest drug dealers in the world, literally peddling opium to the masses in China and we freak out about so-called Yardie gangs, with their drive-by shootings, their attitude and their drum-and-bass music, coming over from Jamaica selling crack cocaine on our streets to our kids. It’s all easy for me to say when I am now living in a leafy suburb of Norwich. Norwich? You don’t get more fucking radical than Norwich.

Have you noticed that since I have been tramping along the inner-city streets my language is getting more out of control?

Down York Way, but it’s blocked off for major roadworks. Gimpo knows a detour. A desolate 1970s estate, then over a footbridge over the main lines into St Pancras. We are now on the edge of Agar Grove Estate, which is primarily made up of three tower blocks. Gimpo used to live in one of them, and it’s where his daughter and ex-partner still live, but they are away so we don’t get the lift and knock on their door for a cup of tea.

Down Camley Street. Under another rail bridge. Hundreds of thousands have been spent doing up this bridge, not strengthening it, or widening it, or anything practical like that but just tarting up all the Victorian brickwork. All part of the millions that are being pumped into the King’s Cross area. Past the locked gates of an inner-city wildlife sanctuary. My mind is going, I’m beginning to lose it. I keepforgetting where I am and where I’m going and what I’m doing. Is this what begins to happen as you get older? We have been pounding the pavements non-stop now for three and a half hours. That is apart from the ten minutes in the café in Crouch End.

Gimpo is trying to engage me in conversation about how the King’s Cross gas works have been lovingly dismantled and neatly stacked up, every Victorian nut and bolt of them ready to be reconstructed.

Then he goes on about all the rebuilding of St Pancras for the EuroStar. I try to take in what he is saying. I look upand nod. This is how my mum must feel. She had a stroke about four years ago and when you talk to her you see her struggling to make sense of what you are saying. Is the pavement pounding knocking out thousands of brain cells with each step? Maybe that is what is disappearing in London – my sanity.

We are now squeezed in between the two mighty stations of King’s Cross and St Pancras and we are being met by a flood of commuters. All of them dressed in black suits, black jackets, black dresses, black skirts, black shoes, black socks. Black, black, black. Except their faces; most of them are white. We are swimming against the tide of them and their blackness.

‘Where are they going, Gimpo?’

‘Home, Bill.’

‘But why this way?’

He explains something about the entrance to St Pancras being changed because of all the building work.

We somehow cross Euston Road. I remember to look the right way and not get run over. Down Judd Street and into Bloomsbury. My sanity is returning with the calm that Bloomsbury always seems to exude with its Georgian squares and University of London buildings. Past the front of the British Museum where there used to be a magic shopthat I loved going into as a kid on the occasional family visit to London. That’s long disappeared. Maybe that’s it. The magic of London has disappeared.

Gimpo has been diligently filming every car, cab, bus and bike which has been disappearing around corners. The problem for him is that with every one of these disappearances at least two other vehicles come into frame when what we had been hoping for was a nice empty frame.

Maybe I should read something into this, something about what appears is always more…No, fuck it! I won’t try to read anything into anything. I will just keep walking.

Out of the peace and quiet of Bloomsbury, across New Oxford Street, a few yards down Shaftesbury Avenue and into Monmouth Street and St Martin’s Lane. The lights are on, bars are full, restaurants filling up, theatres open for business. All around us are people with lives and friends and things to do and talk about. Shiny faces laughing and smiling, getting rounds in, having a laugh, having a life. I can feel the madness creepupon me again. Where’s Gimpo? I’m lost, I’m sinking. My feet keepgoing. Keepstriding. Keep wading through the people. St Martin-in-the-Fields. Horatio Nelson. Where the fuck is that Queen Eleanor’s Cross? Have I made the whole thing up? Turn into the Strand. Cross the road to Charing Cross Station. That must be it, standing behind the wrought-iron fencing. Between the two gates, where the taxis go in and the taxis go out. The tophalf is covered in netting to stop the pigeons shitting all over it. It is all grimy and sooty. I walk around it. There is no notice or placard or anything telling us what it is or why it is here. Nothing to say that I am now standing at the very epicentre of this city, once the greatest city in all the world. All around me hundreds, thousands, millions of people getting on with…no, positively rushing through their lives, and I’m just standing right here in the centre of it all.

Where’s Gimpo? There he is. He is trying to film taxis as they disappear out of the gate at the other side of the cross. I sit down on the ground, my back against the cross, and stare upinto the sky. Still no sparrows.

The plan had been for us to bring sleeping bags and sleep down under the arches by Embankment tube station, where all the homeless used to sleep. Then we would carry on with the second half of this London Slicing In Two walk in the morning, but family commitments mean I have to get the train back to Norwich tonight and we will finish the walk the day after tomorrow. That’s Good Friday. I wonder if Judas has done his deal yet.

Gimpo and I disappear down into the tube station.

Can hardly climb out of bed. Legs stiffer than ever in lifetime. Signs of ageing multiply by the day. Put ‘Queen Eleanor’s Cross’ and ‘Charing Cross’ into Google and get ‘1–10 of possible 20’. I click on the second one, www.rodcorp.typepad.com, and up comes the information.

At the exact centre of London on the site now occupied by the statue of King Charles was erected the original Queen Eleanor’s Cross, a replica of which now stands in front of Charing Cross Station. Mileages from London are measured from the site of the original cross.

When Queen Eleanor of Castile died in 1290, Edward I commissioned 12 crosses, each sited at one of the stopping places her burial procession passed from Lincoln to Westminster. The original cross was replaced, then demolished (the stone was reused to make paving along Whitehall) and in 1863 a rather ornate version was put up in front of Charing Cross Station, a couple of hundred yards away.

You fuckin’ arsehole, Drummond. Why the fuck didn’t you check Google the day before yesterday? I spent all of yesterday walking down a longitude ‘a couple of hundred yards’ from the one I should have been following. All that William Blake visionary madness and me giving it ‘at the very epicentre of blah blah blah’ is just bollocks now. It might be only 200 yards to you but to me it has made all those pavements pounded and words written on the hoof pointless.

Best not to tell Gimpo.

‘Morning.’

‘Morning.’

‘Fancy breakfast before we start?’

‘Yeah.’

We enter an empty Garfunkels around the corner on Northumberland Avenue. I have never been in a Garfunkels before. Hate the idea of them. Strictly for foreign tourists. The full English is surprisingly good.

Plates cleaned, we get to work. Striding down Whitehall, through the swarms of foreign tourists. Past the crapand embarrassing statues of irrelevant generals outside the Ministry of Defence. I mean, obviously they weren’t irrelevant in their day, whenever that day was, but they are to me today and, I guess, to all the tourists. The one of Monty looks good, with his hands behind his back in some non-heroic pose. At least his soldiers loved and respected him. At any rate my dad did when he was out in the desert in 1944.

Anyway, enough of the past. On to Parliament Square. Can’t believe that bloke protesting against the war in Iraq is still there with his ever-growing wall of placards and banners of all shapes and sizes. What he is doing is brilliant. Pisses all over my pack of pointless Silent Protest cards and more importantly pisses over most art being produced in the here and now. Visually, it is stunning. It has an audience of hundreds and thousands. It is seen daily by the people who run our country and all those foreign tourists who don’t. But best of all he doesn’t get moved on. He doesn’t shut up shop. He doesn’t disappear. He just keeps appearing, more and more of him. Or at least more and more of his placards and banners. Gimpo tells me that he doesn’t make them all himself. Other people make them and bring them down to add to his collection. Why doesn’t someone come along and burn the lot? Why don’t the police do something about it? It’s a national embarrassment, that’s why it’s brilliant.

Fuck the badly done replica Queen Eleanor’s Cross that’s not even in the right place. As far as I’m concerned, this man – whatever his name is – is the centre of London. He is the point that all this madness that is London revolves around. Right now, on this Good Friday morning as they are driving the nails through Jesus’s flesh, it’s him, the bloke on Parliament Square, who is my modern Blake and he is building our New Jerusalem with dog-eared placards and tatty banners.

We move on down Millbank, the Thames on our left sparkling in the sunlight. Gimpo films the Tate boat. The one with the Damien Hirst spots on it. The one that takes art lovers from Tate Britain to Tate Modern and back again. Gimpo is filming it disappearing around Millennium Pier.

We cross Vauxhall Bridge, down South Lambeth Road, past all the Portuguese shops. Past Stockwell tube station, which I used to come out of nearly every weekday morning in the late 1980s on my way to Jimmy’s house for us to be getting on with our Justified Ancients of Mu Mu things.

‘There used to be a baker’s in the parade of shops in the next block. I would go there every morning on my way to Jimmy’s for a bag of doughnuts.’

It’s still there. It hasn’t disappeared. I go in. They’ve got a deal going. Four doughnuts for £1. I get four. Gimpo doesn’t want one. Gimpo’s on some sort of no-wheat diet, says wheat saps your strength. I eat two doughnuts, one after the other. Save the other two for later. Feel like Homer Simpson.

Gimpo is wearing his new hearing aid. He started to go deaf after being a gunner in the Falklands war. It’s a pink flesh-coloured one. He wants to get one of the dark brown ones that are made for black people. We pass the National Centre for Deafness on Clapham Road. Turn on to Bedford Road at Clapham North tube station. The legs are feeling good. We should have attempted to do the whole lot in one day. That was my original idea. Walk across London in a day. Green fields to green fields between dawn and dusk. It was Gimpo who thought we couldn’t do it.

‘You know, Gimpo, we should have done this in a day.’

‘Fuck off!’

‘What d’ya mean?’

‘I’d ’ave ended upcarrying you.’

‘Fuck off!’

King’s Avenue. Cherry blossom, daffodils, as well as the cheeky dandelions and saintly celandines I was going on about before. We take a turning on the left, Thornbury Road. And there it is, the back wall of Brixton prison. Gimpo’s home for a few months at the back end of 2002, where he spent Christmas banged up for crimes against himself.

‘They used to throw tennis balls over the wall from here.’

‘What for?’

‘With drugs inside.’

‘What, the prisoners?’

‘No. Friends or family would throw them from the outside, from here in the street. And them on the inside would have volunteered for sweeping up the perimeter yard, between the wall and the block. It was mainly to sweepupall the crapand bog paper we would throw out of our cell windows. But you would phone your friends or family to let them know when you would be doing the sweeping upso they could throw the tennis ball at the right time.’

‘Makes sense.’

We keep walking. Past one of the prison wardens that Gimpo remembers, he’s obviously on his way to work.

‘He was a cunt. Always got the other officers to do the dirty work, sent them in to sort things out when it all started going off.’

We keepwalking. No sparrows. Where the fuck have they all gone? And why?

*

Cross the South Circular into Tierney Road and on to Streatham Hill. The A23. The road south to Brighton. Past the Megabowl. Lots of people out and about on this Good Friday morning. Not that many people look too bothered that Jesus is now hanging on his cross, a gash on his side, some blokes throwing dice for his clobber while he is dying for our sins. Yours, mine and all these people looking fine and dandy on this lovely spring day.

I could never work out what it meant that Jesus died for our sins. Did it mean that I could do whatever I wanted and when I got caught I could say ‘It’s OK, you don’t have to punish me ’cause Jesus has already died for my sins.’ It didn’t seem to work out that way. My sins didn’t disappear. I still got a clip round the ear.

We move on. Streatham Ice Skating Rink, home of the Streatham Raiders Ice Hockey Team. I used to love going to ice rinks. Not for the skating, not even for checking out the girls, but for listening to the over-cranked pop music reverberating around the hall. Hearing Telstar by the Tornados in Ayr Ice Skating Rink is one of my all-time popmoments, upthere with doing stage security for the Damned at Eric’s Club, Liverpool, in 1977.

Don’t get me started on pop moments or I’ll be here all day. We’ve got to keep going.

I like Streatham. This is going to sound patronizing and maybe even racist. When I am in Brixton, I think it must be shit to be black. When I am in Streatham, I always think it must be great to be black. And don’t ask me why, that would take longer than categorizing the pop moments thing.

Still no fucking sparrows. I wonder whether Jesus was able to watch any sparrows while he was up on the cross. When he said that thing about not worrying ’cause God that feeds the little birds in the fields will surely look after you, I always imagined it to be sparrows. Sparrows always look so happy as they squabble about in gangs, chirruping away. It always makes me feel good when I see them getting on with life, whatever their surroundings. So where the fuck are they? What do they know that we don’t and does Jesus know this and should he be told before he dies later this afternoon?

We move on past Streatham Common where a poster is advertising Kite Day 21 April. Gimpo has taken to filming low-flying passenger jets that are flying above us as they make their descent into Heathrow. He is filming them in a patch of blue sky as they disappear behind a cloud.

Pounding down a long straight section of the A23, cars ploughing by, heading for the coast. We take a detour from the A23 but we are still keeping close to our chosen longitude, the one that your man on Parliament Square is on. Down a couple of lower-middle-class suburban streets, Leander Road, Silverleigh Road. Families out in the sunshine. I’m feeling chipper.

Back on the A23, skirt around Broad Green. Somewhere down here is the Mechanical Copyright Protection Society (MCPS) or the Performing Rights Society (PRS) or one of those other official music industry things that used to make my life difficult but now endeavour to make it pleasant. Not that pleasant, but a few bob in the post before Christmas because a song you had a hand in writing has been getting a few radio plays in South America helps pay for the turkey.

On to Purley Way. Croydon rises in the east. I’ve never been to Croydon. Driven past it loads of times, but never got out and had a look around. I like the idea of Croydon.

Gimpo points out a couple of towering chimneystacks to our south-west.

‘There’s an Ikea there.’

Gimpo and I have, over the past few months, been building up a mental map of the country based on where Ikeas are located. No other information is on this map other than Ikeas and their proximity to major centres of population. I think the theory is that you can measure your distance from the heart of modern civilization by timing how long it takes you to drive to the nearest Ikea. I’m not claiming this as an original theory, it sounds more like one a journalist would come upwith. I wonder how long it will take before the concept of Ikea will disappear as a conversational topic within certain classes in London?

Gimpo was right, there is an Ikea.

‘I’m fuckin’ starvin’. We must be more than halfway. Do you reckon there’s any cafés down this stretch?’

‘Just around this bend, Bill, there’s one, but you won’t want to go there.’

‘Why?’

‘You wait.’

And before we round the bend I can see the golden arches peeking over the fence. I start singing ‘McDonald’s, McDonald’s, Kentucky Fried Chicken and a Pizza Hut’. I love singing that song. It has got to be both the most inane song and the one that captures a strand of our culture more precisely than any other in this decade. Was it the Cheeky Girls that sang it? I wonder what happened to them.

I am now resigned to walking into a McDonald’s for my lunch. The place is chocker: kids, dads, young couples, lonely lost souls, gangs of gum-chewing teenage girls and me and Gimpo. I’m fooled into ordering something from their new healthy range. Some sort of chicken wrapthing with chilli sauce and side salad. It’s shite. At least the chips are OK. I really resent the fact that I like McDonald’s chips. I wonder if people will get nostalgic about McDonald’s when they disappear, like my parents’ generation get nostalgic for Lyons Corner Houses? Will the thought of a McDonald’s Happy Meal conjure upwarm feelings inside the children of today in fifty years’ time?

We leave McDonald’s and most of my chicken wrap. The two doughnuts are still in my jacket pocket. I eat them. That makes me feel better.

We take another detour off the A23, through an area called South Beddington according to the map. This is all new landscape for me. We are going up Mollison Drive when I hear something familiar. Something it seems I haven’t heard for some time. It’s sparrows chirruping, just three or four of them in a garden shrub squabbling away like sparrows do.

‘Where have you been? Why didn’t you tell me you were going? What’s going on? Is Jesus dead yet?’

Of course, it must have just gone three o’clock and the temple curtain has been rent asunder.

‘Don’t be fuckin’ daft, Bill,’ says one of the sparrows. ‘Palestine is at least four hours ahead of us. Jesus died ages ago. They’ve already got him in the tomb at the garden of Gethsemane.’

‘Shit, you’re right. I hadn’t thought of that. But look, while I’m doing my Doctor Dolittle bit and you are going along with it, can you tell me why you have all been buggering off?’

‘No, Bill, we can’t. We are sworn to secrecy. And no, it’s got nothing to do with the rumour about the giant sparrow hawk in the sky about to swoopdown and kill us all. Or the racist crapthat we understand that you have been going on about. Any other questions?’

Talking to birds is a bit of a habit of mine while out walking by myself. Obviously I wouldn’t want to be seen doing something as alarmingly stupid as talking to birds in front of a companion. So today I’ve restrained my chatting to the sparrows to the confines of my notebook. What is liberating about this is that in the confines of the notebook the sparrows can chat back. Down on to Foxley Lane and upinto Woodcote Lane. Everything is looking decidedly stockbroker beltish. I hate using tired old clichés like stockbroker belt, but you know what I mean, leafy and wealthy.

There is nobody about, the streets are empty, the gardens are empty, the houses look like they are empty.

‘You can tell only whites live here, none of the others have got this far yet. Maybe in ten or fifteen years’ time.’

‘What do you mean, Bill?’

‘Well, you know, as ethnic minorities climb the social ladder they move further out of any metropolitan centre and deeper into the suburbs. It will be some time before they reach here and even longer before they reach the supposed traditional English village. Ethnics hate the countryside. They’re frightened of it.’

‘You’re talking shit, Bill. What do you know?’

‘When was the last time you saw a black man in the countryside?’

Gimpo doesn’t answer. I notice that the daffodils in the gardens we are walking by are already past their best. I hate the visible signs of the passage of spring. Without trying to be profound, decay follows the promise of spring all too soon. It’s all so fleeting. One moment you see your first snowdrop of the year, the next thing you know the swifts are packing up and heading south again.

We pass through some gates at the top end of Woodcote Lane. A village green opens up in front of us. The green is surrounded by wealthy and wooded gardens. At one corner is an old village shop with a red pillar-box outside. Picture postcard stuff. A war memorial with a long list of the glorious dead from the parish.

‘Looks like you were wrong, Bill.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘The lads playing football.’

I look over. About a dozen lads are kicking a ball about, every one of whose grandparents came from some other part of the globe. I find this somewhat inspiring, that nowhere is safe in this backward-looking country from the multicultural ethnic thing. Wonder what the lads on the war memorial would have thought if they could see this. Embrace change or you’re fucked, that’s what I say. Trouble is, I can say it but I can’t always do it. All that embracing gets harder as you get older.

On to Woodcote Grove Road. Lurching down into a place called Coulsdon. We catch glimpses of open country ahead of us. That’s London almost sliced in two. According to the mapthere is an overground station here. Gimpo gets out his mobile and phones rail inquiries. Seems the trains run at 49 minutes past the hour. It’s 12 minutes past four. That gives us just 37 minutes to get out into the country and back down the hill to the station.

We cross the A23, take a short cut across some major road works, on to the B276. It’s not that I expect you to be thinking, ‘Oh yes, the B276, I know it well, often take that route myself when walking across London.’ I’m only writing it down ’cause that’s what it says on the map. It’s all uphill now. We turn off on to a lane that according to the mapwill take us on to Farthing Downs. We cross a cattle grid. Rough grass, cowpats on the ground. Does this count as open country or is this just parkland? A fresh cowpat smells good. We walk on up the hill. We reach the top. Rural Surrey stretches out before us. A black man strolls past with a pair of walking boots on, clutching an Ordnance Survey map.

‘Look, Gimpo, up there. Are those cows or horses? If they are only horses, it doesn’t count. But if they are cows, then this, in my book, is open country.’

Even with my specs on my eyesight is pretty fucked. Gimpo only needs his specs for reading.

‘I’m not telling you. And anyway if they are cows, you’ve got to touch one of them for it to count.’

Whatever these beasts are they are about 400 yards away and we’ve got only about 29 minutes before the train comes. I pull the bag containing the broad bean plant from my jacket pocket. Scoop a small hole in the ground and plant the beans, in the hope…well, in the hope of something. Get back up and start lumbering towards the beasts. They are cows, big brown ones. When I’m about 20 yards away I stopthen start to sidle upto one and place the palm of my hand on her surprisingly warm flank. She turns her large head around and looks me straight in the eye, as if to say ‘So what does that prove?’

Just then I notice a small flock of sparrows heading south. And I say ‘Hang on a minute lads, I’ve got something I need to ask you.’

But if they heard me, they don’t want to stopand find out what it is. The cow moves off and I’m left standing, wondering what the fuck that was all about.

[Bill Drummond]

All through the summer, drawn by the raw, unswerving energy of the jets, I returned obsessively to Heathrow Airport and environs. I was fascinated by the squat utility buildings of the 1940s and 1950s, but it was the unmapped zone, out beyond the airport’s Western Perimeter Road, that attracted me most.

I would edge upfrom Feltham Station, through the old railway yards and along the River Crane, towards the sound of the planes. At Hatton Cross I would skirt the southern edge of the airport, aiming for the River Colne. Martin S. Biggs, writing in 1934, in his book Middlesex Old and New, described this area as a ‘veritable Middlesex Mesopotamia’. As a dweller on the Northern Heights, I found that this alluvial plain, with its ditches and hatches, had the feel of another country.

I would take my camera and my plant recognition manuals and set out with an eye open for roadside skips and empty houses. I have spent years building up an archive of material – old photos, documents, household objects – recording traces of lives lived in the old county of Middlesex. Retrieving discarded letters, diaries and borough guides from these unofficial time capsules was one of the pleasures of my walks.

It was while exploring the land around Spout Lane North that I discovered Bedfont Court Estate, a colony of derelict smallholdings set upby the Middlesex County Council in the 1930s. For years this little enclave of farmhouses remained hidden beneath the Heathrow flight paths. Later the M4 wormed out from London, while the M25 slashed around to the west, closing in on the farms and concrete tracks.

The estate pre-dated the airport. At the time of its construction there was nothing more than a small aerodrome belonging to the Fairey Aircraft Company. Since the Second World War, Heathrow and its attendant facilities have spread outwards in successive waves. Airport perimeter roads have been laid down – one of them cutting through the edge of the estate as recently as 1947.

I first stumbled across the Bedfont Court Estate during an attempt to visit Perry Oaks, a sludge-disposal works set up by the County Council in the 1930s as part of the West Middlesex Main Drainage Scheme. Liquidized sewage was pumped down the Bath Road from Mogden, near Isleworth, and dried out at Perry Oak – for use on the rich farmlands of the region. During the 1980s concerns about heavy-metal contamination by industry put paid to the recycling of waste and, ultimately, to Perry Oaks.

The sewage works featured in that record of urban wildlife Richard Mabey’s The Unofficial Countryside (1973). Though he doesn’t name the site (in keeping with his precursor Richard Jefferies’s policy of being unspecific about the locale of his subjects), it is clearly Perry Oaks he is discussing. Mabey drew attention to the rare waders using the works as a halt on their migratory flights. Being interested in birds (and sewage farms) I decided to check the place out. I was shocked to find that where Perry Oaks should have been, according to my OS map, there was now a massive building project.

Instead of austere 1930s blockhouses and sediment lagoons, I saw what looked like an aluminium frame for a vast greenhouse. Cranes sliced through the stark horizontal of the airport. Eerie half-glass half-tent structures shimmered across the landscape. Gigantic ramparts curved out of the construction site. Gravel mounds towered over the trees. Checking my map, I found that this area of tracks and buildings was described as the Bedfont Court Estate.

I hadn’t realized that work on BAA’s new flagshipfifth passenger terminal was so advanced, or that Perry Oaks had been earmarked as its location. A glance at the security fence around the main site confirmed that access was impossible. Crossing the Western Perimeter Road, I turned up Spout Lane North, where kennels have been established to board pets while their owners are out of the country.

Spout Lane is obviously old. Ditches run down one side. Tall oaks wrapped in ivy, and dense patches of bramble interspersed with wild rose, line the lane. You could be entering a traditional farming community circa 1914. I found out later that the Spout in question was an ancient fish pond formed by the confluence of several streams and field ditches. In its place is a reservoir holding the drainage from the airport runways.

To the right a little track ran towards some scattered pines. The baying of dogs from the boarding kennels could be heard through dense hedges. On the left I saw the first of the smallholdings: small white houses, their roofs steeply pitched. Desolate scraps of land broken by ramshackle sheds and greenhouses. Signs warned of trespass and surveillance.

Behind the houses, across land dense with thistles and docks, a flimsy wire fence marked the lower slopes of the gravel mounds. It was hard to shake off the feeling that something disastrous had happened here. It was as if a major contamination of the site had occurred, an unreported Chernobyl emptying the area of its inhabitants. Folk memories had been replaced by the blur seen in a moment’s glance from cars speeding through to the new terminal.

Yet the particular resonance didn’t arise from relics left behind by previous users: the broken fences lost in weeds, a burned-out caravan parked in a yard, the dying damson bushes. There was a knotty multifariousness, a strata of cultural associations, evident in the broader brushstrokes of the place. The farmhouses, for instance, seemed to come straight out of the Ukraine in the middle of the last century. There was something of the kolkhoz, of enforced participation, about these buildings, all identical, each plopped firmly within its allotted area of land. The concrete track with telegraph poles had the makeshift feel of militant, revolutionary policy farming: ‘we must feed the cities’. The dumpy little tractors standing by disintegrating shacks might have been loaned out by the authorities for communal use (an impression I later found was correct).

And the piles of gravel: these instantly shifted me to an Industrial North of the mind. I found out, while subsequently researching the site, that the mounds had been heaped up to provide material for the construction of T5. Some of the gravel had been dredged from the River Colne. The mounds also included the crushed remains of Perry Oaks. Under EU legislation, smashed concrete has to be recycled as aggregate.

I climbed over the fence of house No. 6 and wandered around its garden. I opened the door of a small storage shed and looked inside. A battered upright piano, keys like uneven teeth, topped with three old canary cages. A wire basket with flower bulbs, their meristems visible in the dim light. A yellowed newspaper discussing Peter Shilton’s rejection from the England football team.

The weight of years was concentrated in this hidden patch of west Middlesex. Lives, brushed aside by vast economic forces, had formed a residue here. Decades of family activity were implicit in that piano, the memorials to dead pets. Outside once more, I looked in through a window at the front of the house. A little bed was neatly made upin a well-swept room. The smoothed lines of the pink counterpane contrasted with the untidiness of the external landscape. A small extension to the rear contained armchairs, a

padded footrest, plastic flowers on a folding table. By the inner door a pair of green wellington boots stood side by side.

I climbed one of the mounds and gazed across at the North Downs and the Guildford Gapfar to the south. The Harrow petit massif looked tiny, off to the north-east. I could see the glowering dome of Beacon Hill, over near Tring in the Chilterns. Best of all, the half-built T5 stood little more than a third of a mile away, partly screened by some trees. I had accidentally stumbled upon an historic moment: the construction of T5, its spur road displacing the estate at my feet. I tried to take a photograph or two but found that I had run out of film.

Two weeks later I took my friend Mark to the estate. Mark is the kind of topographic commando who has no fear of climbing over obstacles to gain a more intimate view of his surroundings. I have seen him balance precariously above the Thames on a ladder, while boarding a derelict boat. I have swung around just in time to see him disappear through corrugated iron or through a smashed window into some dangerous structure.

Our visit started badly: we were accosted by a vanload of police while walking the concrete track that slices through the estate, providing its main thoroughfare.

A sharp-eyed officer leaned his head out of the van: what were we doing, in what he described as ‘a sensitive area’? I had done enough background research to be aware of the local population of tree sparrows and pipistrelle bats. I said that an interest in bird life had brought us to this backwater. The police drove away, shocked but satisfied. We climbed the mound and Mark took some shots of T5 and the bespoiled zone.

Minutes later we were climbing through a window into No. 8. Any hopes I’d had of finding documents for my Middlesex archive vanished with the sight of the bare rooms, the dusty echoing staircase. The house had been meticulously stripped of its fittings. The plinth for a vintage sewing machine and a stainless-steel spoon with an ornate handle were all that we found. Mark reckoned he could smell asbestos. I sensed troubled, uncomfortable lives, wheezing years spent wrestling a livelihood from the surrounding acres. We hung around a minute or two listening to the scraping of birds’ claws on the roof, then we got out.

There was a barn and a breeze-block fallowing sty attached to one of the houses. Rusting clamps were fixed to steel worktables. A hepatic bodkin or two lay in the dust. I picked up some photographs of old folk playing with dogs and a stained copy of Summerhay’s Encyclopaedia for Horsemen (newly revised 1975). Mark did me a favour, wrenching a cast-iron wheel from a cement-topped gatepost that guarded a moulded resin fish pool and a grove of planted cypresses.

Ghosts flitted about as the sun set and tree sparrows settled down for the night. The houses were sad in the evening light, their chimneys pointing accusingly at the passing jets. I gazed at my retrieved photos and wondered at the years spent beneath flight paths, the stoicism it required to endure in that economic and social gapbetween coarse-faced smallholders with decrepit tractors and the international pilots and svelte hostesses in fuel-devouring machines overhead.

A bat flew upand down the tree line seeking out moths. Mark – ever the product of his rural Irish upbringing – snapped some pears from a tree at the garden’s edge. It was the best pear I’d ever eaten. We watched the yellow trucks and bulldozers, still trundling across the Bailey bridge, heading for T5. It was a small triumph that these fruit trees had managed to keepa gripon their rightful inheritance in the face of this rampant onslaught.

T5’s brief includes the eventual ‘rehabilitation’ of the site. Presumably this will involve utilizing the type of applied ecology that makes BA’s landscaping of their HQ at Prospect Park in Harmondsworth such a joke. Groves of ‘traditional’ trees, sculpted tumuli and enforced hedgerow biodiversity (in accordance with Hooper’s dictum that you can tell the age of a hedge from the number of tree and shrub species per 30 metres, averaged across the length of the hedge) seem an insufficient salve for the greed being enacted here.

I returned a few weeks later with Michael Collins, a photographer who specializes in highly detailed studies. In one of his prints, of a railway yard in Purfleet, a specimen of charlock is clearly visible from a hundred yards off.

I ran into Michael at the London Metropolitan Archive while researching the Bedfont Court Estate. He mentioned the difficulty he was having accessing T5 for one of his shots. By introducing him to the gravel mound, I could provide him with an unsurpassed shot and, hopefully, gain a high-quality print or two for my Middlesex Archive.

The following Saturday Michael picked me up in his van and we sped down to Heathrow. We carried out a quick reconnaissance while waiting for the weather to shift. A nod from Michael and we were hauling his heavy plate camera and tripod up the side of the mound. There was a heart-stopping pause while the camera was set up, then Michael applied the mysteries of his craft. We were perched above T5 and one of the airport runways, in clear view of traffic rolling along the Perimeter Road below.

Michael took twenty minutes over a couple of shots. Far below, a white police van drove southwards along the Perimeter Road. As we were packing up I saw the vehicle edge in along the track running off Spout Lane. We tumbled down the slope, rehearsing our explanations.

The police were waiting for us. They were armed. I didn’t help by asking one of the officers if he would hold our box of film while I struggled over the fence. He refused. Slinging their submachine-guns across their chests they separated us. Michael got the nice cop while I was left with an embittered cynic, intent on aggravating the already tense situation.

While my documents were being scrutinized and the radio crackled back info on my (impressive) criminal record, a jeep pulled up. A burly guy from T5 told us that he was going to photograph us. If we had any objections, it was pointed out that they had the power to detain us, intimately search our persons and confiscate the expensive photographic equipment. Satisfied that we weren’t armed with hand-held Blowpipe surface-to-air missiles, Michael’s policeman relaxed and discussed the finer points of photography. My man was determined to extract a shame-filled apology. ‘Are you aware of the current international situation, sir?’

The man from T5 Security took our portraits with a digital camera. I was advised to stay out of the area – irritating, given my devotion to old Middlesex. Though I made brave and resistant noises on the journey back to London, I never returned. Those submachine-guns had taken the pleasure out of the project.

For all I know the estate has since gone the way of Perry Oaks. Soon BAA will begin the push for Runway Three and the villages of Harmondsworth, Sipson, Longford and Harlington will also disappear, swept aside by the urge to find depth and richness elsewhere in this world. Always elsewhere.

[Nick Papadimitriou]

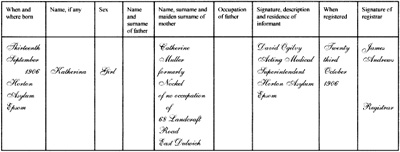

22 June 1906

…a female patient, Catherine Muller, admitted on the 14th November, 1904, and who, therefore, has been in the Asylum about one year and seven months, is found to be pregnant. On the 17th December last, as reported to the Committee, she escaped from the Asylum, from which she was absent rather less than an hour and a half. The condition of the pregnancy and the medical record points exactly to this time as the date of conception. She will give no reason, either to her husband or myself, as to the cause of her condition.

…The patient being of German nationality and unable to speak English, arrangements had been made at Dr Bryan’s request for Mrs Freedman, Interpreting Attendant, from Colney Hatch Asylum, to attend with a view to obtaining particulars from the patient.

According to the neuroscientists, when we see a tiger’s tail, stretched out, gold and white and muscular from behind a rock, our brain at once jigsaws in the invisible body-parts, so that we think Ah yes, a tiger, and take to our heels or reach for the camcorder. We have an inbuilt jigsaw-fetishist, that can’t let a length of fur on the ground be a length of fur, but searches its memory for the missing pieces, and makes up a whole it thinks it can relate to.

You start with lined pages of fuzzy type, bound into a great decaying ledger, red-brown leather-dust on your clothes and hands, and something inside you tries to fill in the tiger.

Matron entertained a visitor last night. Except for ten in the extreme cold weather, no chicks above one day old have been lost; this is attributed to the use of Chikko dry chick food for all under one month. 1,800 cauliflower plants have been transferred to the colony at three shillings per thousand. The habitual frequenting of public houses by female staff should be strongly discouraged.

Reading the minutes is a thinned-down version of living as a patient in the asylum. There’s too much going on, the asylum farm, the production of calico drawers in the needle room; the activities that are held to be therapeutic but end up simply sustaining the institution. Two thousand patients and as many staff. How do you get these people to take notice?

George Grundy escaped from a walking party at about noon on 3rd August. This is probably the case which has given rise to reports in the local paper that a patient was at large in a nude state. Several parties were sent out to search but were unsuccessful.

Or perhaps it’s like being on the Sub-Committee. Mr Chairman, I have a few questions for the Medical Superintendent. When Catherine was brought back after her escape, did she seem particularly distressed? What support is she having through her pregnancy?

28 September

The Medical Superintendent reported that patient Catherine Muller was safely confined of a female child on the 13th instant and that she now gave the information that the sexual congress took place in the Horton Lane on the night of her escape.

Questions for the Medical Superintendent (soon to be fired), the Poor Law Guardians of St Giles Parish: their concept of care and treatment, their neutron-bomb failure of imagination, vaporizing humans, leaving the walls intact. Questions, more to the point, for Catherine. How have you been coping? What do you want to happen?

26 September

READ letter from London County Asylum, Horton, intimating that Catherine Muller gave birth to a female child on the 13th instant.

RESOLVED that in acknowledging the letter they be informed that the Guardians take it that the London County Council will make provision for the maintenance of the child, as in their opinion the trouble has been brought about owing to the neglect of duty of the Officers of the Asylum in allowing the patient to escape.

24 October

READ letter from the Asylums Committee, London County Council, intimating that they have no legal power to pay for the maintenance of the child of Catherine Muller, born in Horton Asylum.

Questions for her daughter, whisked off to the workhouse.

Sometimes you catch a tiger by the tail and all your brain offers you is a few stripes, the musculature of a thigh, a plushy paw. It’s not clear if your fingers can’t let go, or if your arm is caught in not-yet-visible jaws.

Subsequently, the patient, who was in bed, was seen by members of the Sub-Committee. The patient was afterwards dressed and taken to the grounds with a view to ascertaining which road she took when she escaped. No reliable information could however be elicited from the patient and finally she stated that she was not going to have a baby.

You understand that questions are not the answer.

*

And why this particular tiger, anyway? Why not naked George Grundy in the streets of Epsom? Or Minnie Crawford, whose unnamed husband is addicted to morphine, and threatens to poison her and kill himself if the doctors put Minnie ‘under restraint’? The asylum minutes are full of terrible stories, in direct language, among the farm yields and insubordinate nurses: and more stories there, and still less information.

Catherine Müller (just once she is given the courtesy of an umlaut) is German and speaks no English; though she ‘appears to understand what is said to her’. (The reverse does not seem to be expected.) From December 1904 till April 1905 her husband didn’t come to visit her; now again, she has had no male visitors for a year. For a year and seven months, nobody in the asylum has felt it necessary to communicate with her at anything beyond the most basic level. She is pregnant for six months before anyone notices; and when they do, all their communication, through the hastily summoned interpreter from Colney, is designed to prove they are not responsible.

Catherine, come away from the dark wards.

Come out of the laundry, the desolate bleached aprons,

gasp of the steam pushed out of seamed sheets

and trapped behind windows. Look,

out here in the rosebeds the crinkled frost has fallen

and covers hope like an overall. Catherine,

Katharina, slip through the gates to your own language.

Here in the lane the beech-trees know everything:

how you must lift

up through your body again, how you will find

in the frost on the bright beech-leaves your own voice calling.

Just so far imagination can take you. Is it her own voice Catherine meets in the lane, the long-missed surrender to another body, penetration as the essence of being known; or some chancer who comes upon a bewildered young woman, and finds it no effort at all to grab and rape her?

The London Metropolitan Archives and the Family Records Centre are two minutes’ walk apart, behind Exmouth Market. The same people busy themselves in both buildings: neatly dressed white people of a certain age, single men, couples, siblings, mothers and daughters, with notebooks and the requisite soft pencils. These are the resurrectionists, digging for grandparents and great-grandparents in parish records and marriage registers. The shop at the Family Records Centre sells family-tree posters, ready for completion. To be in either place, rifling through the tomes, without a provable DNA connection feels reprehensible; illegitimate.

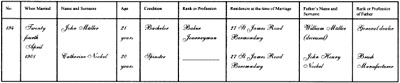

The Parish of St Giles Camberwell has left two bluntly titled Registers of Lunatics Chargeable, from 1890 to 1906 and 1906 to 1912. In the first of the huge landscape ledgers, four inches thick, with the front cover missing, the pages loose and grubby, is Muller, Catherine, aged 23, married, Church of England, housewife, of 68 Landcroft Road. Husband’s name: John Muller. The printed columns of the register speak to the Poor Law authorities’ expectations: Age on first attack: 21. Where previously treated: Horton. Duration of existing attack: 3 weeks. Supposed cause: unknown. Epileptic: no. Suicidal: no. Danger to others: no. Admitted: 14.11.04. In the second volume the details are the same; but John has moved house, from Camberwell to Ebury Street, Pimlico. There is no date of discharge.

The asylum admissions registers, with patients’ personal details, are closed till 2017 and 2021. (Poor Law records don’t seem to have the same restrictions.) The agendas and resolutions of the Sub-Committee are marked in the index unfit for consultation. The Board of Guardians has a little more to offer.

1 August 1906

We saw Catherine Muller, and looked carefully into the facts of her disease, and inspected the record books. The fact of the escape was reported to the Lunacy Commissioners on December 18th, that is within two clear days. Mrs Muller looked ill and anaemic.

What did the Committee do with that information? Did anyone in the asylum act on it?

6 December 1907

We have this day visited the Horton Asylum and seen the 72 inmates chargeable to the Parish, and are sorry to say very few show any sign of ever being discharged.

They all appear to be well cared for.

*

A German woman with an anglicized name, not speaking English, still in the asylum in 1912 and perhaps later, during the First World War.

If not the person, perhaps at least the context.

At the time Catherine was admitted to the asylum, German people made up the second-largest immigrant community, after Russian Jews: around 56,000. Most were economic migrants, from the impoverished regions of Germany. Many worked in East London in sugar refining, hard, unhealthy work; or as waiters, clerks, bakers. The German Hospital in Hackney (now the Metropolitan Workshops) had 120 beds, nearly always full, and saw 20,000 to 30,000 outpatients a year.

Already in the years before the war, when Catherine was living in Landcroft Road and later in Horton, there was growing hostility towards German people. The usual cries: they were paupers; they worked for low wages. Prejudice as ever was licensed by politics, the diplomatic tensions between the countries. The paranoia could have been from Horton: all these bakers and tailors were working for the Kaiser, preparing for the German invasion of Britain. By September 1914, with the war just started, the Met had received 8,000 to 9,000 reports accusing Germans in London of espionage. A lurid spy literature appeared and flourished. The same mad speeches in the same locations: Joseph Chamberlain, Limehouse, a hundred years ago:

And behind those people who have already reached these shores, remember there are millions of the same kind who…might follow in their track, and might invade this country in a way and to an extent of which few people have at present any conception.

Petty racism doesn’t reach the chronicles. Still we have seen this twitching tail before: graffiti, insults shouted down the street, children beaten upon the way to school. You could hardly live in East Dulwich and not know it.

With the war, prejudice gained full expression, in Parliament as much as on the streets. Day two produced the Aliens Restriction Act, enabling a series of regulations to control where Germans could live and travel, who they could meet. John Muller perhaps in one of the long queues at police stations for compulsory registration. The Daily Mail, already xenophobic, complained that some Germans were changing their names – perhaps to avoid being taken for spies – and in October 1914 this too was outlawed. Internment of men of military age began; over 13,000 by 23 September, at which point there was no more accommodation.

Anti-German riots began to flare, the most sustained racist disorder ever in Britain. Someone threw a brick at a shopin Deptford High Street, and the building was torched; two other shops were attacked, the contents destroyed. In the usual logic of blame-the-victim, the response was to start internment all over again, though some were released later for lack of space. Women, children and men over military age were deported.1

There is no indication of the nature of Catherine’s illness, nor what the asylum considered to be its cause. For all the women committed for enjoying sex, or having illegitimate children, for all the lack of cure and the brutal treatment, some at least of the 100,000 asylum patients in 1900 must have been suffering from what we too would describe as mental illness; or, if we mistrust our own time’s diagnoses, from distress that they couldn’t find relief for. Whatever the label the asylum gave Catherine, however we might describe her state of mind, we know being hated is bad for the mental health. Day-to-day racism can get under the skin, erode the self-confidence, make it harder to maintain the sense that one is active, contributing to the well-being of the planet. The riots, ten years after she was committed, were within a few miles of Catherine’s home: Deptford, the Old Kent Road, Brixton, Lee Green, Catford.

Or perhaps the neighbours were specially kind to her.

Which would be better: four more years in Horton, till the end of the war, or to be deported? Would anyone bother to deport a woman who had already spent ten years in an asylum? If she’s going back, she will need to recover at least by the time she’s fifty. Among the Jews and Roma and homosexuals, the first victims in the camps of the Holocaust were the psychiatric patients.

*

She sits still.

The rocking-chair tilts her gently back, then forward. She sets her feet firmly on the pink-and-blue rug. The chair stops, in mid movement: just there.

Now the only movement is her lungs, steadying; the blood flowing past the pulse-points in her wrists.

She sits still in her rocking-chair, in her rented rooms: in her land-lady’s house, in what is now her street. Although she was brought here, not knowing where it was, it seems that now she has chosen all this: the bright sunlight slanting down from the dormer window, the two attic rooms with their sloping ceilings, the smell from downstairs where her landlady is cooking, the front garden, the suburb. She sits like a stone dropped in a pond, and feels the concentric circles spread around her.

I hope I will not fall to the bottom.

Outside on the street some children are playing a game. She can hear their heavy jumps, between ragged pauses, their voices calling out words she doesn’t understand. A bicycle judders over the cobbles. A woman calls to someone. A dog squeals.

Nobody here will ask her to do anything, except pay five shillings to Mrs Pilgrim the landlady on Fridays. At first Mrs Pilgrim seemed to hope she would talk; but she shakes her head. Later she will start to put English words to things. Thank you, she says when the tray is brought to her door.

If she goes out of the house she will start to say Good morning. So far she does not want to leave the house.

So far I do not have the strength to leave it.

I can choose not to do what I say I have no strength for.

The rocking-chair is made of dark varnished wood, and upholstered in worn brocade. The smooth wood cools the spread palms of her hands. The rug at her feet is faded pinks and blues, knitted from soft rags. In the bedroom there is a patchwork counterpane.

She thinks: no one else has just this bedspread, made by a woman, Mrs Pilgrim perhaps, from old summer dresses. It will not return from the wash and be allocated to another patient.

I am not a patient.

The light pours in with a torrent of bright dust. The room smells of dust and lavender-bags. When she has eaten, the smell of boiled potatoes and casseroled meat will fade from the air slowly.

She sits here waiting to find who she has become. Though she thinks to find out she will have to get to her feet, tilt the rocking-chair forwards; go out of the door and down the two flights of stairs. When the front door latches behind her, she will be a person, in a street with children and dogs and bicycles, a city where there are men apart from doctors. There she will be one particular person, in the way that the pieces of dress have become a quilt.

While I sit here I do not need to be anyone.2

*

Upstairs at the Family Records Centre are the census findings. The 1901 census survives in gunmetal drawers full of microfiches. Landcroft Road is on RG13/501, folio 134, page 138; or RG13/501, folio 169, page 173; or possibly RG13/502, folio 17, page 25.

Dark replicated pages lurch across the screen. Either the censustakers recorded answers just as they walked, along one side of a road, down a turning and another turning, then back on the opposite side to the main road; or the pages have been copied in nil order. There are bits of Landcroft Road scattered here and there. You come close to 68 and turn the fiche on to the following page, but that proves to be blank, or you’re somewhere else completely. You can’t tell if you’re skipping pages. You can’t remember which fiche you’ve seen already. Then abruptly you see it, 68 Landcroft Road, and whoever is living there it’s not the Müllers.

There are other places to look for a tuft of fur. Marriage certificates list husband’s occupation, and even occasionally wife’s. You have to scour.

Downstairs is filled with the percussion of metal shelves struck by heavy ledgers being removed, replaced. You heft down the register on to the tilted desk, turn the thick pages, run a finger down to the surname; then close the volume again, back on to the shelf and find the next, K–S or S–Z, quarter by quarter, year by year. In 1904 Catherine was twenty-three; she could have been married from 1897 on.

A baker; one of the main occupations open to Germans. Is a journeyman one who’s done his apprenticeship, and works in someone else’s bakery, one of those shops to be torched thirteen years later? And then they are living at the same address, before the marriage; living together; or recent immigrants, perhaps, both in lodgings in the same house; or Catherine as the lodger of Mrs Müller, senior, now a widow, or…

If Catherine in her twenties speaks little English, the chances are that she came to the country as an adult, or at least a teenager. The shelves of red birth registers stretch back to the far reaches of the room: 1960, 1940, 1920, 1900. Catherine was born in 1881. The records start, mercifully, in 1880. The heft of ledgers, the finger down the page, the slot into place again. There are no Nockels; or rather there is the occasional Nockels, plural, but no baby Nockel, Katharina or Catherine.

The Creed Register lists admissions to the workhouse, those who have come to the end of their own resources and find themselves submitting to this shame, to be unable to fend for themselves, their families. Domestic servants, bricklayers, housewives, retired factory workers; and this child. Everyone else, however destitute, has a given name. In two months surely her mother named her? Even the child of a rape, once she was born; even the child resented for bringing even more punishment upon her mother.

The red ledgers again.

Muller, Katherina ....................................... Epsom 2a 24

Katherina: of course she was Katherina, her mother’s real name, her given name, before she or her father or husband or some official at the port of entry decided she had to be English. In German it’s Katharina, with an a. Like the umlaut on Müller, the subtleties, the distinctions by which you know yourself as a person with a past, a culture separate from this one, are ignored.

Assuming Catherine was literate, and cared. Assuming she didn’t choose the variant, and spell it out herself.

Katherina, two months old, in late autumn, leaving Horton, the indoor world of the ward and the day room; abruptly weaned from her mother’s milk and her mother’s consoling or reluctant arms; carried on a cart or bus or train to Gordon Road, Peckham, and the grim workhouse. It had to be grim: the Poor Law principle of less eligibility required conditions to be worse than any its inmates would otherwise live in. Is there a baby ward, a row of cots, a wet-nurse brought in? Then four months later, another move, to the infirmary, wherever that is: out of the workhouse care.

Nothing in the Horton list of baptisms. Nothing more in the workhouse register. There were children’s homes, run by the Board of Guardians. Workhouse children lived in the homes till they were seven or eight, then were boarded out. Workhouse children stood out awkwardly in school, in ill-fitting clothes, not knowing how to play. After boarding out the boys were sent to work on the land, or to training ships. At fourteen the girls came back again to work unpaid in the homes, on the slim pretext that this would prepare them for domestic service. This could have been Katherina’s childhood: children’s home, private household, children’s home.

The Poor Law girls were incapable of doing the ordinary work of a house, such as lighting a fire or laying a cloth. They had little knowledge of ordinary household equipment…They had no idea of the value of money or shopping.

A Poor Law girl would scrub a floor well enough if told, ‘Begin here, and go up to there.’ This she would do more patiently and ploddingly than the local girl, but as soon as she was told, ‘Make the kitchen look nice and bright,’ she had not the least idea how to set about it.

The results of such a childhood were traits which made it difficult for the girls to get on with other people.3

Without parents to stick up for them, or a mother’s advice on dealing with harassment, young women leaving the children’s homes were vulnerable to seduction or rape by the master of the house where they worked, or his sons. Many went into part-time prostitution:

They were usually small and looked younger than their age. Moreover, they were broken to direction, had little knowledge of the world and were hungry for affection…If they disappeared, there was no one to make a fuss.4

Broken to direction. Was that what happened?

The register of children maintained at the workhouse care. The register of children boarded out. The register of children adopted or emigrated (a transitive verb).

Clara and Jane Dark, aged seven and ten, admitted to the workhouse children’s home on 6 January 1906, when their parents enter Gordon Road Workhouse. Discharged 13 January. Back the next day till the 25th; Clara discharged and readmitted the same day. They both stay till 1 February: this time their father in the infirmary, the mother at home. Back again the same day, this time till 10 March. In July the two sisters are ‘adopted’, which seems to be something less than permanent.

Other children are in and out the whole time. Four-year-old Albert Miller is there on every page, from October onwards. Rosina, Alfred, Ernest and Beatrice Davis, aged between nine and four, have an alternative surname, Churchill, and a ‘reported’ father, Alfred Churchill, carpenter, in Gordon Road with all the other parents, except their mother, Rose, address unknown. Alice, Frances and Lily Marshall, aged eleven, six and three, father dead, mother in Bexley Asylum, boarded out and then adopted. Henry Mason, aged eleven, foundling, emigrated to Orleans, Ontario. Rose Clarke, aged sixteen, adopted by Reverent Perdue in Ontario from the Waifs and Strays Home, Whitehaven.

No Katherina.

Then there is only one way left to try to trace her. The death rate of illegitimate Poor Law children was twice as bad as for the legitimate. Back across Exmouth Market, behind the bank become a pizzeria, to the black ledgers. If Katherina isn’t recorded among the living, perhaps you can find her among the dead.

1907. 1908. 1909; April, June, September, December of each year. Every year that her name isn’t there with the other Mullers, three or four in each volume, you have kept her alive. The clack of ledgers returned to the metal shelves, the aftershave and perfume of other searchers, the weight of the tome as you lift it from the shelf and turn with it in your arms to the reading desk. 1910. 1911. At 1914 you are competing with a man in a tweed jacket and sunken unsmiling cheeks, who grabs each volume as if you might scarper with it. You’re tired; perhaps you’ll give up for today. You leapfrog to 1919, on the other side of the shelving unit, and begin working backwards.

*

It isn’t Katherina that you find.

Muller, Catherine 37 ....................................... Epsom 2a 40

Catherine dead; presumably still in Horton; perhaps in the great influenza epidemic. No lodging with Mrs Pilgrim, no rocking-chair; no afterlife of trying to find her daughter, and not finding her and living anyway, rediscovering music and food and sex and friendship. No learning to live without the institution, no flashbacks to the terrible treatment there, no difficulty with other people or herself to be ascribed to Horton, thirty years later. It’s the day before the Bank Holiday weekend; urgent to get hold of the death certificate, whatever paltry facts are there to console you. You pay twenty-three pounds for an express search, and wait and wait even so, the threeday weekend, the Tuesday when it is printed, the two days that first-class post takes to reach Tottenham.

Not influenza, which at least was shared with some equity across swathes of the world and all kinds of people, not least Dr Lord, Medical Superintendent of Horton, though he survived and worked long after the war. TB, the disease of the poor and overcrowded.

And Banstead. Horton, to the satisfaction of Dr Lord, was a military hospital for most of the war, the patients – the ordinary, mad patients – dispersed to other asylums around London. In spring 1915, 2,143 people were evacuated, each with a medical report and a case paper (but not the detail of Catherine’s husband’s name), ‘a full personal kit and as far as possible a change of clothing’.

GPs refused to certify patients to the remaining asylums, because the conditions were known to be so bad.

More Sub-Committee minutes, for Banstead this time. No mention of the transfer of Horton patients; but in November 1917, the year before Catherine died, a special report from the Medical Superintendent.

As the Sub-Committee are aware, it was at the end of last year that our death rate began to rise to alarming proportions…

In 1916–17, the death rate among male patients is 21 per cent, and 12.5 per cent among women. This is before the flu epidemic has started. As a man you have a one in five chance of dying, as a woman one in eight. He goes on to chart the principal causes of death:

Male | Female | |||