You can find most German businesses and individuals in Das Telefonbuch, an online repository of addresses and phone numbers that German citizens with landline telephones have to opt out of to be excluded from.

No cybercafé can compare to physically going in person to a German Biergarten or other outdoor eatery. But a menu of websites and strategies can help you hit the ground running when that trip to an ancestor’s Heimat becomes reality. Whether your specific desire is to track down modern-day relatives, find a German researcher, or complete some virtual task in Germany, this chapter will put some items in your toolbox that will prepare you well for such an adventure.

While many German institutions lagged a bit behind their American counterparts in moving to digital systems, e-mail is now available when querying about most things. While this may not apply to small or out-of-the-way villages (and less widespread in the area of the former East Germany), you can usually find some avenue of electronic communication to the area you’re seeking.

You also need to leave behind those American presuppositions we talked about in chapter 2—remember Germany’s relative compact geography as well as its penchant for locally kept records. Note that to get the best results from contacting German archives, you’ll need to follow some special procedures. These will be covered in chapter 12.

Many individual villages in Germany now have their own websites, and finding them can be as easy as plugging in www. plus the town name and the default German web URL suffix of .de or by putting the village name and the name of the German Land it lies in into a Google search. If either of these ways bears fruit, write your request—about town records, archives, or just the fact that you plan to visit—in English unless you are relatively fluent in German. They will usually reply in German, so you’ll need to translate that reply using tools discussed in chapters 2 and 3.

Of course, you need to realize that the person who receives your e-mail at (or for) the German village may not have even a passing interest in genealogy, and it’s helpful to recognize that by making your initial e-mail short—and, perhaps, by merely asking for the recipient to direct you to someone who is interested like a local historian, a Heimatmuseum (a history museum in the town devoted just to that village), or a civil or religious archive for records of village.

If the e-mail given on the town website doesn’t yield a reply or you couldn’t find a website for the town, then it’s time to play the “tourist dollars” card. Germans are nothing if not savvy businesspeople, and if you write to the area’s tourist board, it often will forward your message to an official of the village for an answer.

Be aware that when dialing telephone numbers in Germany, you may omit the first zero from city codes (like our area codes) inside Germany when using a landline. However, you’ll need to include the leading zero if you are dialing from outside Germany.

We’ve talked about looking for surname concentrations in chapter 3, but what if you have a lead on a particular individual or city? Well, here’s something that’s certifiably better than in America—all of Germany’s landline telephone numbers (and some cell numbers, too, if the individuals opt in for this) can be found together in one online directory—Das Telefonbuch <www.dastelefonbuch.de>. This directory is also a more comprehensive search than American phone books (and their online equivalents) because Germans can’t just tell the phone company they want their numbers unpublished. Rather, they need to furnish a narrowly drawn security reason for this to be done. As with America, however, the trend among young people is to have only a cell phone.

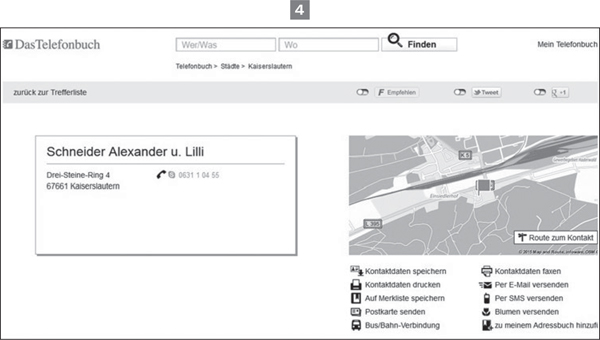

The logistics of using this national telephone directory are fairly straightforward. The home page (image A.) displays boxes marked Was (literally, “what”—which is where you put the surname of the person or business name being searched) and Wo (“where,” if you want to limit your search to a certain town).

You can find most German businesses and individuals in Das Telefonbuch, an online repository of addresses and phone numbers that German citizens with landline telephones have to opt out of to be excluded from.

Click on Finden to execute a search. Other types of searches can be done using the icons in the middle portion of the page (the lower portion of the home page is not shown on the image, as it contains advertisements, as does the rotating “billboard” right under the Was/Wo/Finden boxes). Among the other specialized searches that can be done by clicking on the icons in the middle are ones that add social networking contact information; a reverse search to use if you have a phone number and want the individual’s name; and directories by business categories (like the old yellow pages). Remember you can get a rough translation of the names of the special categories by feeding the page through Google Translate <translate.google.com>.

This is a case in which America and Germany have something in common: both have organizations for their professional genealogists. However, just as genealogical periodicals written in English are indexed in PERSI (the PERiodical Source Index), while German-language publications are found in Der Schlüssel (literally, “the key”), so too are English and German professional researchers organized into separate groups. The Association of Professional Genealogists (APG), based in the United States, has some German members. However, a much smaller organization of German-speaking professional researchers is called the Verband deutschsprachiger Berufsgenealogen (which the group translates as the “Association of German-speaking Professional Genealogists”).

The Germany-based group’s website can be accessed in German, English, or French. Like the APG, the German organization has a code of standards that each member must adhere to, though the German association’s list of standards are stereotypically German in that they are lengthy and specific. Also like the APG, members of the German association are not specifically credentialed as genealogists (two American-based groups, the Board of Certification for Genealogists and the International Commission for the Accreditation of Professional Genealogists offer, respectively, “Certified Genealogist” and “Accredited Genealogist” designations).

The decision to hire a professional, especially one in a different country, can be difficult and perplexing. First of all, you may be one of those researchers who takes pride in doing his own work. And, of course, some people just plain think that everything in genealogy (maybe in life, too) should be free. If a hobbyist does not see the value in paying a professional—someone with specialized experience who will get a pedigree correct, probably in a fraction of the time—nothing the professional will do will be adequate.

I had searched for many years—including about a dozen trips to the Family History Library in Salt Lake City—to find the German hometown of my surname immigrant ancestor, Johannes Beÿdeler. Finally in 2010, just a half an hour before I would have left Salt Lake City again empty handed, I found his 1727 marriage in the records of Gerolsheim, a village in the German Land Rheinland-Pfalz. As luck would have it, I’d already booked a trip to Europe, primarily to see the once-in-a-decade Passion Play in Oberammergau. Gerolsheim would fit nicely into the itinerary immediately upon my arrival in Germany.

As I continued to make plans for the trip, I read a short article on Wikipedia <www.wikipedia.org> about the village and found a town website; however, the website listed no e-mail to contact anyone there! According to the Wikipedia article, Gerolsheim was part of a collective municipality (in German, Verbandsgemeinde) called Grünstadt-Land, and the Gerolsheim website showed that the village was connected with other wine-producing villages in a tourist consortium called Leiningerland.

The Leiningerland website listed an e-mail, so I sent a short note asking if someone could meet me in the village and allow me to purchase any collectibles—steins, stained-glass crests, history books—from Gerolsheim. In just a few days, I was contacted, in somewhat passable English, by the town’s deputy mayor, Klaus May. He wrote that he would be glad to meet me at his home and then take me to see the Ortsbürgermeister (village mayor) named Erich Weyer.

And so it went. My girlfriend and I drove from the airport in Frankfurt to Gerolsheim, where May and his wife met us. We walked with May to the town hall where Weyer was waiting. I purchased the Gerolsheim collectibles, and the mayor cracked open a bottle of the locally produced Riesling wine. Our trip was well under way! We toured through the town and later the Mays and another couple took us to Germany’s largest wine festival in Bad Dürkheim—all on our first day!

Today, I’m friends with Klaus May on Facebook <www.facebook.com>, and we occasionally exchange messages. Truly, the tourist bureau created a great connection for me with my ancestral hometown!

But if you do see the potential value of hiring a pro, you need to address personal and logistical concerns. Feel free to ask for several references in America who you can contact about the professional’s work. Give the professional a complete rundown on what sources you’ve consulted and what you either know or suspect about the ancestor being researched. In exchange, the pro should be able to give you a short summary of what his or her plan is for your research money.

And speaking of money, you’ll need to know how to pay the foreign genealogist. This will vary from one professional to another. Some have American bank accounts that allow them to easily deposit American checks, and more are taking credit cards. PayPal is a popular option, too. If you run into a situation in which the only option is a transfer to a German bank account, you can do that, also—and we’ll go over how to do so as part of chapter 12’s section on paying for German archives.