Begin your research on FamilySearch.org by seeing what resources are available for German researchers.

The landscape of genealogy research is changing. As someone who cut his teeth toward the end of genealogy’s “Gutenberg age”—the era of books, paper records, and record keeping—I knew when the tipping point toward “digital first” was reached. I had returned from the Family History Library (FHL) in Salt Lake City, Utah (the crown jewel of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ genealogy efforts), with several generations of new records for a client with ancestors in Württemberg.

Because the village of origin had been supplied by the client, I hadn’t bothered to plug the immigrants’ names into FamilySearch.org <www.familysearch.org>, the ever-growing digital arm of a genealogy project undertaken by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (often simply called “the Church” in Utah and by its members). But when I did, I found that some of the information I had found by painstakingly searching microfilms of German church records was already in searchable databases on the FamilySearch site.

While genealogists who aren’t Mormon might sometimes be blasé about or express a less-than-serious attitude towards some rites of the Church (such as offering baptism to deceased ancestors), the Mormon commitment to genealogy, founded on the principle of an eternal family, is worthy of respect and an undeniable boon to family history researchers.

Starting as the Genealogical Society of Utah and now branded as FamilySearch, the Church’s efforts to preserve the ancestral history have ranged from funding a worldwide microfilm program beginning in the 1930s to heading extraction efforts that put hundreds of millions of names into the International Genealogical Index (first on microfiche in the 1973, then migrated to CD-ROMs in the 1980s). After decades of this work, the Church has created the world’s top research repository in the FHL and is now digitizing that stock of more than two million microfilms (with searchable indexes) for its FamilySearch.org website. Each step of the way, the Latter-day Saints have been the leading source for German genealogy information, and today FamilySearch.org remains indispensable.

It’s said that FamilySearch.org is the world’s number one free genealogy website, and this is the one of the few times that such a claim isn’t an overstatement. FamilySearch.org is a veritable hydra of a site: Even when you’ve struck out with one resource, you’ll have plenty more to choose from. A description of the site and its holdings is worthy of its own book—indeed, there is one: Unofficial Guide to FamilySearch.org by Dana McCullough (Family Tree Books, 2015), available at <www.shopfamilytree.com/unofficial-guide-familysearch>. This chapter is going to review a few basics about the site and dwell on the many features of interest to those doing German genealogy.

Because it’s free, FamilySearch.org is a great place to start searching for your German ancestors. Whether using the databases, browsing through digitized records, looking at the FamilySearch Catalog to plan microfilm research, or using one of the many learning tools such as the FamilySearch Wiki, you can’t go wrong with FamilySearch.org. You do not have to register to use the site, but you likely will want to do so to enable you to post trees as well as order as-of-yet-undigitized microfilms for viewing near you (more on that later).

FamilySearch.org’s home page currently consists of four menus: Family Tree, Memories, Search, and Indexing. While all these options have items that may be useful to you, we’ll be concentrating on the many uses of Search (image A.), as well as mentioning Indexing and its implications for German genealogy researchers.

Begin your research on FamilySearch.org by seeing what resources are available for German researchers.

Hovering over Search will reveal more specific options (image B.), each of which will be described in detail in this chapter:

FamilySearch.org has a number of features you can use in research.

As has been said earlier in this book, see what you can get for free before you pay for it. Many resources that you can access on paid websites can also be found on FamilySearch.org.

Also remember that while FamilySearch is speedily marching toward full digitization, some of its FHL microfilm and book resources are restricted (e.g., owners or copyright holders of the resources in question) from giving users at-home digital access—or even from being digitized at all. Some archives only allow Church members to have remote access to the online records. Note that you may get a notice that online films are “temporarily unavailable” even though they’re restricted films. Whenever you get such a notice, try asking FamilySearch Support whether the restriction is truly “temporary” (which would mean someone else is using the resource) or essentially permanent. You can still learn about such restricted resources on FamilySearch.org, and we’ll show you what the best ways to gain offline access.

And whether they’re restricted or not, a substantial portion of the microfilm (including many German church records) and book collections (including loads of tomes related to German genealogy: pedigrees, histories, record abstracts, and the like) is not yet digitized. That’s another reason why we’ll talk about using the Catalog on FamilySearch.org: to plan research if you go to Salt Lake City or order films to a local FamilySearch Center run by the Church.

The two FamilySearch.org assets of widest interest are its collections of digitized and indexed records. While you might think of these two categories of resources as heading toward each other like speeding railcars that will come together in a spectacular explosion of genealogical records access—instead of a colossal train wreck!—for now they are on separate tracks and both worthy of the German genealogist’s attention.

The thing to remember is that in many cases (at this point) the imaged collections are not indexed, and the indexed collections sometimes won’t have images. Regardless of whether the collection is indexed, you’ll want to access an image of the record because it likely has additional information and context that an index might not capture.

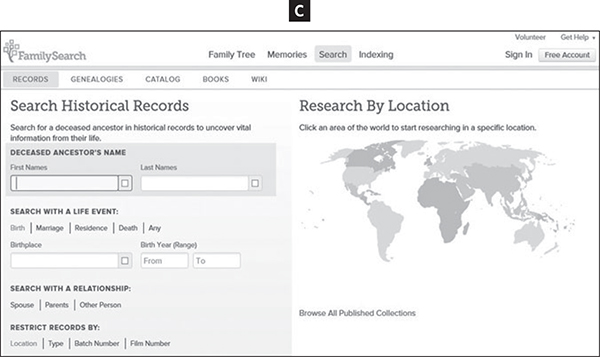

You can access both the digitized and indexed collections by going to the Search tab on the FamilySearch.org home page and clicking on Records, which yields a number of ways to access records on the site similar to the overall Search form (image C.).

FamilySearch.org’s Search Historical Records page allows you to search for records by type, year, name, or country. You can also search in individual countries by selecting a region on the map of the world, then by clicking the name of an individual nation.

On the left-hand side (or on top, depending on the width of your computer screen) of the page, you’ll see a search form titled Search Historical Records. This is your primary entryway to the indexed collections since, naturally, results from the images-only collections won’t show here.

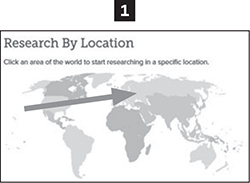

On the right-hand side (or the bottom depending on width) of the Records page is a map of the world titled Research by Location. If you click on the Europe map, a listing of countries comes up; choosing Germany will show you the collections, both indexed and image-only, that have German records. This leads to a page called Germany Indexed Historical Records that has a search form. You can search all the collections pertaining to Germany or drill down by choosing one particular database. At the bottom of the Germany research page is a listing of the image-only (unindexed) collections, which can be called up for individual browsing.

If you don’t wish to limit yourself to the collections marked with the Germany title, you can also hit Browse All Published Collections under the maps of the world. The page that results (titled Historical Record Collections, image D.) allows you to look at the names of the better than two thousand collections (more than fifty of which are strictly German records) or “Filter by collection name” and pick up collection titles relevant to your search that may not have Germany in the title. A camera icon appears when the collections have images as opposed to merely indexed records.

While not all of the microfilmed collections have been indexed, you can still browse through all of the published databases that have been digitized.

It stands to reason that if records of the vital events of birth, marriage, and death are a genealogist’s big three resources, then those indexed collections of documents from Germany would be the largest. And so they are. About fifty million such records and their substitutes are kept in the FamilySearch.org indexed collections, under the following titles:

Each of these databases can be searched separately. And while they each contain millions of records, they are by no means a complete record of any of the three vital events between the dates noted; they represent the work of the FamilySearch Indexing volunteers.

We’ll look at the Germany Births and Baptisms, 1558–1898, database as a step-by-step example. The following search fields are available (you can leave almost all of them blank, though you do need to fill in a surname):

The First Names, Last Names, and Birthplace boxes can be checkmarked to return only data that exactly matches the search criteria.

What’s great about these collections is that the Citing This Collection information at the bottom gives you the exact FHL microfilm number from which the information came—see this chapter’s section on the FamilySearch Catalog on deciphering this information. This will be helpful if you decide you want to see a microfilm copy of the original. In the case of this record, for instance, that’s important because the original will have baptismal sponsors’ names and seeing it in the context of the original might offer additional clues. For example, the baptism above this one may show the Heuschele parents were sponsors for someone else’s child—and that someone else might be a relative. Or there may be a marginal notation in the original that will have an impact on your search (such as the death of the individual) that didn’t fit into the pieces of data being captured during indexing.

You’d think that having access to such huge databases can’t help but be good, right? Well, you’d be right and wrong. Yes, these databases are great first spots to check for your ancestors’ respective vital events. But determining exactly what you’ve looked at when you do searches in these databases is an errand in imprecision. The closest you’ll get are coverage tables in the FamilySearch Wiki that show the number of records from the respective German states.

Other indexed databases are substantially smaller than those offered by the “big three,” but they can still be worth accessing depending on your geographic interest. Some also link to images of the records in question. Holdings include several databases of “church book duplicates,” some civil registrations, census records from Mecklenburg-Schwerin, and a few collections of city and municipal records. A couple of substantial collections include church records from places such as Pomerania and Posen that are no longer part of Germany.

Databases of American records, of course, may be relevant to your German research, especially if you’re still at the stage of discovering your ancestor’s Heimat. Two collections with German in their titles are United States Germans to America Index, 1850–1897 (an incomplete indexing of Germans in the US passenger arrival lists), and United States, Obituaries, American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1899–2012 (more than four hundred thousand images and indexes of obituary records taken by the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia).

In most cases, especially in the First Names box for FamilySearch.org search forms, don’t checkmark the Match exactly box, since Germans could carry several names but not use them all in every record. By having the search function exclude any results that don’t exactly match your search terms, you’ll likely exclude many potential results.

Some four dozen sets of records consist of currently unindexed digitized collections. While about half of the collections in this category are either city directories or miscellaneous city records for many of Germany’s midsize cities, a number of church and civil registers have been digitized, as well as a few military, probate, and Jewish records. As with the indexed collections, a number of databases will appeal to those looking for areas no longer within Germany.

Because urban immigrants are sometimes lost in the shuffle and therefore more difficult to document, the privately published city directories (Adressbücher) and other records in these collections can be helpful. While you’ll notice considerable variance from city to city as far as what the collections marked “miscellaneous city records” contain, in a fair number of cases they include some of the following types of documents: marriage application documents, emigration records, citizen rolls, population registrations, local censuses, guardianship and adoption records, guild and apprenticeship records, and tax records.

The site has a number of digitized collections that include church and civil registers not previously microfilmed but still available through the FHL. Some of these contain only a few parishes’ records. The largest quantity of such records in the digital collections are from the German states that now make up Hesse; however, most of these Hessian digitized records are not available for viewing on the Internet and require the user to look at them at a FamilySearch Center or to be a logged-in user of a partner organization (i.e., they must be a Church member). You can also find a number of indexes to funeral sermons, which serve as alternatives to death records.

In all cases, look carefully when you drill down into a digital collection and understand how large (or how limited) the offerings included are. One example is Germany, Hessen, Darmstadt, City Records, 1627–1940, which lists an invitingly broad date range for its collection of the documents from this midsize German city. Included in the collection are four types of records: Aufnahmen von Bürgern und Beisassen (records of citizenship and temporary residence), Auswanderungen (emigrants), Bevölkerungsverhältnisse (population list), and Heimatscheine (certificates of local citizenship). Only the population lists start in 1627; the others begin as late as the early 1800s.

Another database, Germany, Prussia, Pomerania, Stralsund, Church Book Indexes, 1600–1900, on the other hand, contains more than it advertises because it gives an abstract of the original records (that is, it includes more than just a name for the index entries, which are on scanned index cards) and also includes the town of Voigdehagen.

You’ll recall that you can get a list of the image-only databases. While these collections may take longer to search, they still provide valuable information for your research. The following step-by-step takes you through to an individual database of records that has been digitized but not yet indexed.

You may already be convinced that FamilySearch.org has a lot to offer German genealogy researchers, but there are many more ways the site can help you seek out Deutsch ancestors. Whether you seek additional background information, need to find offline materials held by the Church (and access them either at a local FamilySearch Center or in Salt Lake City), want to share information with others about your family trees, or mine the many family history surname books that have been published, FamilySearch.org can help you. We’ll look at each of these aspects one by one.

Literally hundreds of articles on the FamilySearch Wiki are relevant to German genealogy, profiling geographic areas, different record types, and even history. In many cases, the articles are written by FHL staff, many of whom have credentials in some way and all of whom are subject experts.

The Learning Center is accessed by clicking on Get Help in the upper right-hand corner of the FamilySearch.org home page, then selecting Learning Center under Self Help in the popup menu that results. The list for Germany on the left-hand side of the page shows about fifteen video courses. The courses, in a webinar format, include a variety of basic and intermediate topics. The center also includes other FamilySearch.org classes and links to classes and educational material elsewhere on the Web.

Volunteer indexing has been around for decades, and volunteers have been assisting with Mormon genealogy projects since 1921. Indexing started in many genealogical societies by going through a record or set of documents and noting the names or other items to be extracted on 3x5 index cards, then alphabetizing the cards.

But, just like so many things, it’s come a long, long way!

In just the nine years of its existence, FamilySearch Indexing has taken volunteer transcription efforts to an unprecedented level via computer technology. In 2015 alone, more than a quarter-million contributed to the indexing effort, and more than one hundred million records were completed. Indeed, FamilySearch Indexing is well past the billion mark in total records completed.

The indexers, currently spread out working on about five hundred projects, are the ones whose work allows valuable genealogical records to be freely searchable online, making it perhaps the largest crowdsourcing effort of any type, anywhere. The projects vary in size and length, but FamilySearch Indexing attempts to post work every few months, even “publishing” (that is, posting the work on the FamilySearch.org site) partially indexed work on larger projects that take years.

Anyone—not just Church members—can join in the indexing effort, which can be accessed most easily by going directly to <www.familysearch.org/indexing>. Currently, participants download a program to use for indexing, and a browser-based indexing program is in the works. As a way of improving the indexing product, every image is indexed by two different indexers, and if they differ in their interpretation of the data, a third, specially trained indexer called an “arbitrator” breaks the tie on what the index should say about a record. Even with this auditing and a quality-control process, FamilySearch.org moves fast in making information available; FamilySearch Indexing currently publishes a project within ninety days of its completion.

It’s truly a selfless effort that enables millions of FamilySearch.org users worldwide to easily find information they need in records.

We’ve given you a good taste of the types of German resources that FamilySearch.org has online, but the site is also the key to the full length and breadth of records that the FHL system has available in one medium or another. Many types of German record groups found online are also represented in the still-offline holdings: church and civil registers, tax lists, land records such as hereditary leases (which can be especially valuable in areas such as Saxony where church record survival has been spotty), and so forth.

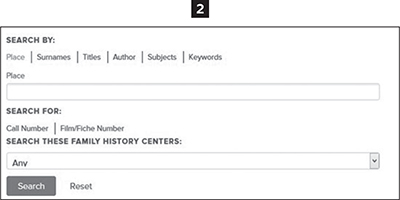

In addition, the catalog also details the microfilms, microfiche, books, and periodicals that often include histories of specific towns or regions, abstracts of historical records, and genealogies of towns and families. It also notes whether materials are in the digitized and/or indexed collections on FamilySearch.org.

While it’s a superb compilation of the world’s genealogical materials, the catalog has limitations that should be acknowledged. In any catalog of this size, there will be some inconsistencies in the subject headings under which the records are grouped. Some are easy to account for: When does a book on military history become one on military records, and how will it be categorized? A diligent researcher will obviously check for both. On the other hand, you could have the unlikely experience of finding Vital Records under Politics and Government, since those vital records are normally created by the government. (They can also be found under Church Records if they are the church book duplicates that were created by the churches but required by some German states as precursors to formal civil registrations.)

In the FamilySearch Catalog, it’s like World War I never ended: The catalog as well as the entire FamilySearch system assigns villages to German states (noble jurisdictions) they were a part of during the Second German Empire period from 1871 to 1918.

The Church operates a network of FamilySearch Centers around the country (often in local Church branches or buildings) that can be your “close-to-home away from home” for microfilmed resources that haven’t yet been digitized. To use it, you’ll need to register for a free FamilySearch account. Once you do that, choose a FamilySearch Center where you want to view your films; FamilySearch calls this your default center. Since different centers have varying hours and technology capabilities (scanning, printing, etc.), you probably want to check out those things (if more than one center is within a reasonable distance) before choosing your default center. You can find more information on the FamilySearch Centers on the bottom left-hand side of the FamilySearch.org home page.

Despite the oodles of online resources we’ve been telling you about, you still have substantial reasons to make the trek to Utah. Reason number one is to tap into the expertise of the FHL staff, as sometimes a personal explanation of records, organization schema, or results beats computer correspondence. And, of course, you may want to use the online FamilySearch Catalog to plan offline research at the FHL in Salt Lake City. You can put together lists of microfilms and books you want to examine well in advance of your trip. Another good strategy would be to connect with library staff ahead of the visit to make sure the specialist you need will be available during the time you’re in Salt Lake City. When you search the online catalog, you’ll also want to take note of any microfilms marked as being in the vault, since these microfilms need to be retrieved from off-site storage and therefore should be ordered immediately upon arrival.

FamilySearch’s Family Tree has the laudable goal of having only one profile per person. However, with the many different skill levels among genealogists using the service, deciding whose data trumps whose can be a nightmare. Take caution when viewing other people’s trees. You never know how much (or rather, how little) research they’ve done to support their ancestor’s profile.

You can keep track of your research and create a profile of your ancestor by making a family tree on FamilySearch.org. Go to the Family Tree tab on the FamilySearch.org home page, then compare your existing family tree to others in the FamilySearch Family Tree database. Unlike most other websites, FamilySearch.org is working towards “one tree,” in which all family trees are interconnected and each person in the site’s family trees has a unique ID number. As a result, your family tree is, in a way, for the whole FamilySearch.org community; anyone can view or change information about deceased individuals on your tree or connect their cultivated family tree to yours. In addition, FamilySearch.org’s Family Tree function has many tools to add sources, comments, photos, stories, video, and audio clips to your ancestor’s profile. The Family Tree also uses a software called Puzzilla <www.puzzilla.org> that gives nifty assistance with descendancy research (that is, probing into cousins of your ancestors).

Fed up with searching for records yourself? Try turning to family trees published by others. Under the Search tab, select Genealogies and search the databases there, including Ancestral File, the Pedigree Resource File, the International Genealogical Index (which we’ll discuss later in this chapter), and Community Trees. You can search all of these at once, but be aware that Ancestral File and Pedigree Resource File, which are mostly user submitted, are filled with many duplicate trees and unsourced entries. They can be valuable for clues to real records but are inherently unreliable. Community Trees pull from well-sourced trees compiled by FamilySearch.org staff in attempts to create full-town genealogies.

You can also look at other users’ pedigrees. Go to the Family Tree menu on the FamilySearch.org home page and click Find to search other users’ trees for your ancestor. Note that if you have already started a computer pedigree in other software and want to upload it to FamilySearch.org while avoiding double-keyboarding, you need to upload it here at the Genealogies tab under the Search menu rather than under Family Tree.

FamilySearch.org has collections made from microfilms of original church registers (called Kirchenbücher or KBs, for short) as well as church record duplicates (Kirchenbuchduplikate or KBDs, for short). The KBDs are recopied versions and therefore slightly less reliable as sources.

The venerable International Genealogical Index (IGI) merits a separate section from the Ancestral File and Pedigree Resource File databases because many of the entries in the IGI database were extractions from baptismal and marriage records found in German church registers. Therefore, it’s a much more reliable database than the other two (which were based on submissions from users who often supplied no sources for the information included) and still has ways of helping you with your research.

Sometimes using the IGI is a way of “turning down the noise” of everything found in a full-fledged FamilySearch.org sweep. And even if your particular ancestor isn’t found in the IGI, running a search of the surname you’re looking for (as long as it’s not too common) may yield some helpful hotspots—villages or areas of Germany in which the surname is found. Go to <www.familysearch.org/search/collection/igi> to search just the IGI.

The first thing to know about this collection is that, unlike its name might imply, Family History Books contains more than just books. It’s a collection of nearly two hundred thousand digitized genealogy and family history publications (including magazines, monographs, and of course books) thanks to a collaborative effort between FamilySearch’s FHL, the Allen County (Indiana) Public Library, the Houston Public Library’s Clayton Library Center, the Mid-Continent (Missouri) Public Library’s Midwest Genealogy Center, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Brigham Young University campus libraries, and several other repositories.

The collection (image E.) includes family histories, county and local histories, genealogy magazines and how-to books, gazetteers, and medieval histories and pedigrees. Some of the items can be accessed from home computers, but others are covered by restrictions that require the user to be in the FHL, a FamilySearch Center, or one of the partner libraries to access to the digital copies. For books still under copyright, only one user worldwide can access such a book at any one time (since that’s legally the same as using the book at the original library).

Searching the database can be done from anywhere, and the every-word search capability at least allows users to get more detailed information on what printed sources may contain and if it’s of interest. Using the Advanced Search form (image F.) allows users a number of options to narrow down hits to a reasonable number by limiting searches to such items as titles or publications that contain certain words or phrases.

The future of FamilySearch.org seems easy to predict: more, more, and more! Well, more of everything except microfilm, but that will in turn feed the “more” for the online side of the Mormons’ genealogy effort. The change from microfilm to full digital storage—predicted to take as long as a century when it was first initiated less than a decade ago!—now has an estimated completion date of the end of the decade.

One reason for that acceleration has been the partnerships FamilySearch has built with the for-profit end of the genealogy block, namely Ancestry.com <www.ancestry.com> and MyHeritage <www.myheritage.com>, which have invested heavily in helping FamilySearch.org digitize the remaining microfilms. In exchange, those for-pay services acquired the right to also show many of the FamilySearch.org collections on their own subscription sites.

Unless FamilySearch is able to negotiate new contracts with the owners of “restricted” microfilms (mostly, for our purposes, German church and civil archives), those digital products will remain usable only at the FHL in Salt Lake City or by visiting FamilySearch Centers. While it would be great to see such renegotiation, don’t bet on it: Many German archives look at their records as revenue sources (as you’ll see in chapter 8 about Archion <www.archion.de>, the new Protestant church records for-pay site) rather than believe that this kind of public information should be broadly available. The likely result is that a substantial number of the digital films will require researchers to go to FamilySearch Centers, which hopefully will see an uptick in resources to help researchers after a number of years of neglect (presumably because so many people want to do genealogy strictly at home).

With the current microfilm rental system, a patron orders films, waits for them to be mailed to the FamilySearch Center, views them, then needs to start the whole process over again if, say, the records show that the ancestor’s parents came from a different village. With digital viewing, the researcher will be able to move on to a new digitized film as if he or she were in Salt Lake City!

While this process continues, FamilySearch is also putting into place features such as “thumbnail galleries” (which allow users to browse indexed entries and the digital original records together) as well as icons in the online catalog to indicate what medium or media (microfilm or digital images) a particular item currently can be accessed on. FamilySearch is also accelerating its effort to reduce the time lag (currently around ninety days) between indexing and publishing those indexes on the site; the indexing arm hopes to dramatically cut that lag over the next couple of years. Not only that, but the browser-based indexing program that’s in the works will allow indexers to “work in the cloud” instead of downloading a separate program. The exciting debut of a “community indexing tool” that allows users to add comments and make clarifications or corrections to indexed data collections is also on FamilySearch.org’s horizon.

The partnerships that FamilySearch has forged are likely to continue since the money that the for-profit outfits can add to the mix is important in getting rights to records and paying for the digitization process. In addition, as the mover behind the RootsTech conference now held annually in Salt Lake City, FamilySearch is encouraging technological innovation on all genealogy fronts. Some technologies in very early stages of development even attempt to use OCR (optical character recognition, which is how most indexing of books and newspapers is now accomplished) to create indexing for German script documents. With FamilySearch’s track record, it wouldn’t be surprising for the organization to help lead such an effort, which would create the next revolution of access to millions of handwritten records.

If the browsable record image collection you’re looking at has index pages (but hasn’t been fully indexed), use these divisions to your advantage, then use this form to track your browsing efforts. Fill in these boxes with each index you find to help keep track of possible record images that list your ancestors. You can download a Word-document version of this worksheet at <ftu.familytreemagazine.com/trace-your-german-roots-online>.

| Surnames Found on Index | Record Number | Digital Record Image Page Number |

|---|---|---|