The MyHeritage home page is your gateway to accessing the site’s many features.

When you’ve been doing genealogy for more than thirty years (and when half of that time has been as a professional genealogist), the gaps in your own personal tree are likely to be the most stubborn of problems. One of those frustrating roadblocks came tumbling down a couple of years ago when my home state of Pennsylvania turned its older death certificates over to public records, eventually resulting in online access to these records. Such easy access allowed me to quickly pull the death certificates of siblings of my direct-line ancestors, some of which had more information on parents’ names than my particular great-great-great-grandfather’s certificate. As a consequence, I was able to add Heberling to my list of ancestral surnames.

But trying to find information about the Heberling immigrant, who appeared to be a German or Swiss man named Rudolph was, well, trying—that is, until I did a Google search, where the only helpful hit directed me to one of the millions of family trees on MyHeritage <www.myheritage.com>. The person who had entered that particular tree stated that Rudolph was of Swiss origin (without any sources, of course, so I took that with a grain of salt), but what really got my attention was that it showed his immigrant arrival specifically on the ship Isaac on September 27, 1749, at the port of Philadelphia. Now this was something I could check out in the Pennsylvania German Pioneers by Ralph B. Strassburger and William J. Hinke (Pennsylvania German Society, 1934); of course, I had previously checked that book’s index to no avail. But what I found was a man making an X for his signature, by which the captain or a fellow passenger had written Rutolph Haberly, a spelling corruption that hadn’t occurred to me. In an instant, this family was no longer “trying” to me.

This example of success demonstrates that a critical mass of websites with large numbers of searchable family trees will inevitably be of some use to you. And “large numbers of family trees” is a specialty—perhaps the top specialty—of the internationally based MyHeritage enterprise. As we’ll see, MyHeritage also has searchable databases of records and some substantial bells and whistles to its searching algorithms that can especially benefit beginning genealogists looking for quick finds.

As befits the site’s name, MyHeritage has more of a worldwide membership base than perhaps any other single genealogy group. As a consequence, MyHeritage is offered in nearly four dozen different languages. This can be particularly useful when families from different parts of the globe collaborate on a single family tree. MyHeritage has some eighty million registered users, including about three million Germans. The site’s users have compiled close to thirty million family trees, and that figure doesn’t even include those from the completely free MyHeritage affiliate Geni <www.geni.com>, where millions more have uploaded their pedigree information.

MyHeritage offers users a limited amount of family tree space with some functionality for free and owns the Family Tree Builder software. Looking at its record databases requires one of a few different subscription plans, which include Premium and Premium Plus. While you can create a relatively small family tree for free, paid subscription is also required depending on the volume of family tree information stored on the site. Many genealogical societies provide a discount on membership, so seek out those deals to make the best use of your money.

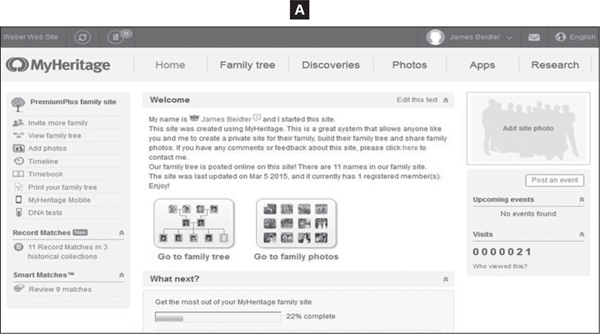

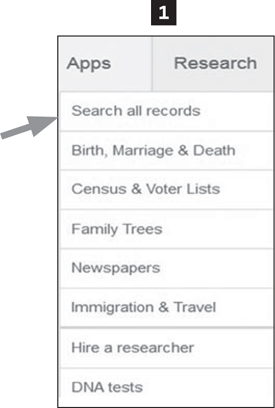

Your home page (image A.) will vary once you’ve set up a family tree, but the primary tabs at the top will stay the same. Hovering on the Family tree tab will bring up a list of options. Choose Family tree on the top of the list (image B.). Next you’ll see a form to put in a person’s name and dates—fill that in, and you’re off and running.

The MyHeritage home page is your gateway to accessing the site’s many features.

Family trees are MyHeritage’s most prominent feature.

When researching in some databases that return locations as part of the textual research result, click on the place name to view with a map showing that place. This feature is a convenient shortcut to see where that village is located (though sometimes it picks up the name of the village’s district and displays it instead of the actual village).

MyHeritage has several specialized searching technologies that can help users build a family tree and search through others’ quickly. For people who are literally just beginning a family tree online, MyHeritage offers the Instant Discoveries function, in which a user new to MyHeritage is asked to enter basic information about himself and his parents and grandparents to receive on-the-spot discoveries, kind of a genealogy speed dating experience. MyHeritage says it tries to minimize false positives but, of course, identifying false positives partially rests on the skills of the new user, who is likely to be an inexperienced researcher.

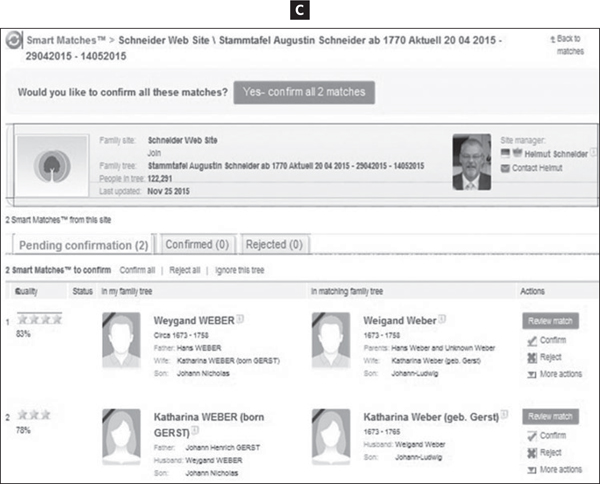

Once a person has created a family tree on MyHeritage, she can use the Smart Matching process (image C.), which takes individuals on your tree and compares them to millions of trees created by other MyHeritage users around the world in the same order as the shaking leaves at Ancestry.com. MyHeritage presents potential matches with a percentage score, indicating how closely its search algorithms say the results match. You can then confirm or reject if the two entries are the same person. The Record Matches technology works somewhat similarly but comes from records discovered in SuperSearch, automatically including a summary of additional records and individuals in family trees relating to it.

MyHeritage’s Smart Match, like Ancestry.com’s “shaky leaves,” allows users to compare their ancestor’s profile to profiles from other users’ family trees and attach relevant information.

The site also has a Record Detective technology that attempts to use any single record found in SuperSearch to list additional records and individuals in family trees that may generate new leads and discoveries. Finally, Global Name Translation attempts to make adjustments for names (as well as nicknames) in different languages and alphabets, feeding back results not just in the language entered by the user. You can use a box (checked by default) on the SuperSearch form called With translations to activate this technology.

Once you get past the huge number of family trees on MyHeritage, the exclusive offerings of records are somewhat modest. You can view the site’s databases related to Germany at <www.myheritage.com/research/category-Germany/germany?sac=1>.

Its biggest databases (German births, marriages, and deaths) will look strikingly familiar if you’ve read this book, because they are the same databases that were compiled by FamilySearch.org and shared with Ancestry.com (and, just like Ancestry.com, MyHeritage uses the threefold-higher number of “records” to inflate the count). In addition, data from FamilySearch Family Trees also shows up in MyHeritage search results.

MyHeritage does have a large database of West Prussia Church Books that appears to be unique, but the problem here is one of sourcing. The database description is vague on whether these are extractions straight from the church registers or whether (as is found in some parts of Germany) those registers have already been extracted previously. In the latter case, you might need to be on the lookout for transcription errors made when abstracts of the records were created from the extracts.

Other resources include volumes from printed genealogy compilations and periodicals such as the journal Gothaisches Genealogisches Taschenbuch Der Freiherrlichen Häuser, the four volumes of Schlegel’s American Families of German Ancestry in the United States, and the publications of the Pennsylvania German Society. Like Genealogy.net, it has many volumes of the compiled genealogy series Deutsches Geschlechterbuch.

Despite having images of the originals attached, some databases can only be searched instead of browsed. And a fair number of the resources don’t have images at all, just a list of textual search results. For example, the West Prussia Church Books database has no way to drill down to individual villages and then browse records from just that village (though of course the village name shows as part of the text result).

The future of MyHeritage promises more of its already established strengths: its global reach and its technological savvy. The service helps families “discover, preserve, and share their family history in an accessible and instantly rewarding way.” MyHeritage’s stated goal is to keep developing additional technologies that bring users and discoveries together with the least amount of muss and fuss.

In short, the story of MyHeritage is that the site was “first to the party” in leveraging what might be called the “family effect” of using public trees as the carrot to bring more people in each family into the site’s fold. And while it’s late to the party on digitizing actual records, MyHeritage is gamely attempting to make up for lost time. Where German records are concerned, it’s true that, despite so many records that are online at one or another of the other major services, many German records (especially church and civil records) reside in backwater areas in Germany, still in local hands awaiting technology to descend upon them. MyHeritage’s goal is to work even closer with the societies and organizations that are the custodians of these records in new partnerships.