Viticulture is the science and study of all things that happen in a vineyard—and a lot can happen there. Most winemakers would tell you that how a grape grows is the single most important factor in determining the quality of a wine. With today’s technology, a winemaker can compensate for many faults, but truly awful grapes are an insurmountable obstacle.

Viticulture: the science and study of grape growing.

Oenology: the science and study of wine and winemaking. (What happens once the grapes are harvested.)

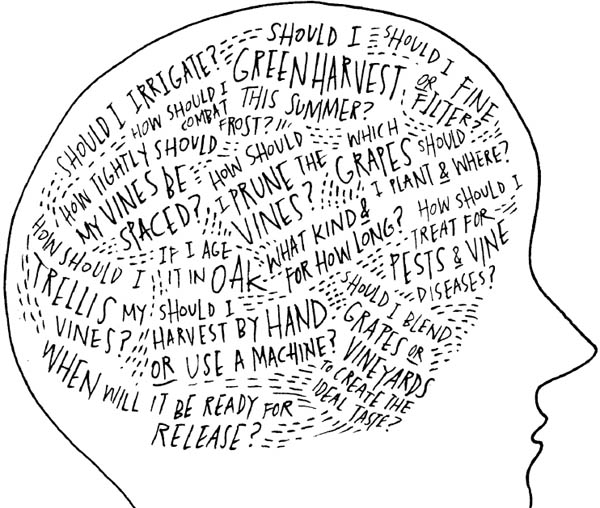

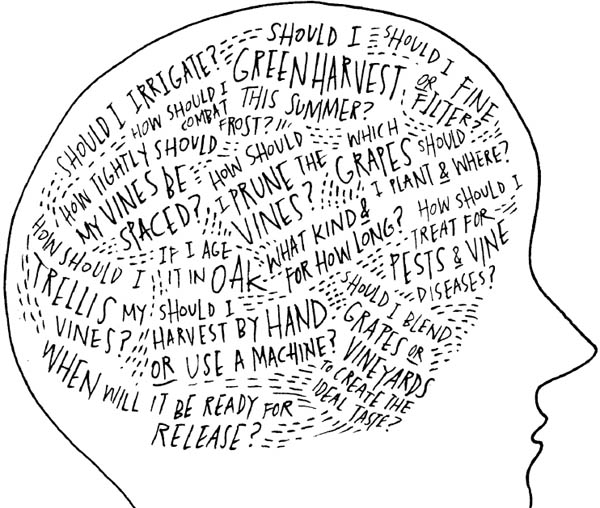

When it comes to viticulture, there are thousands of choices a winemaker makes. All of them combined have a serious impact on the finished wine.

Site Establishment: Where to plant? Which grapes to plant? Which clones to plant? How to arrange spacing of the vines? How to trellis the vines? Stay on budget? Install an irrigation system? If so, what kind?

Farming: How to manage pests and diseases? How to manage frost? How to manage irrigation? Hiring a great crew? Managing the crew? Stay on budget? Fertilize? Farm organically? Farm bio-dynamically? Plant cover crops? Green harvest? How to prune? When to harvest? How to harvest?

Clone: Grapevines are ambitious plants that mutate easily, readily evolving their genetic code to adapt to the environment. This is awesome for the vine’s survival, annoying if you’re trying to produce a consistent style of wine. Grape clones are cuttings from an existing vine that share identical genetic information. Planting clones not only affords a grape grower more predictability, but it also enables him to select grapevines with DNA specifically suited to his environment (or terroir, see page 60) or even with certain characteristics or flavor profiles. For example, here are three of the most popular pinot noir clones, and what they bring to the party.

Pommard: Wines from this clone are sometimes known for having a meaty, gamy edge.

Clone 113: Perhaps the most elegant of pinot noir clones, with perfumed aromatics.

Dijon 828: Noted for its large, long, and skinny clusters, this clone contributes deep color, focused sweet berry fruit flavors, and excellent retention of acidity.

Brix: The Brix scale is the U.S. system used to measure the sugar content of grapes and wine. The Brix (sugar content) is determined by an instrument called a hydrometer, which indicates a liquid’s specific gravity (the density of a liquid in relation to that of pure water).

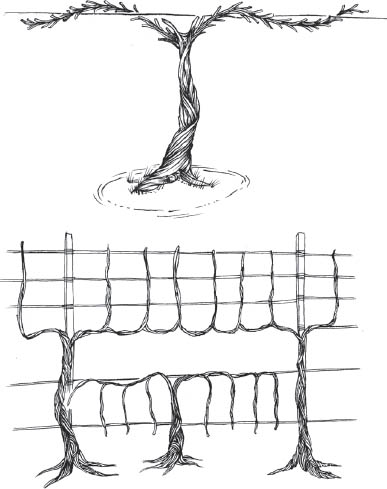

Trellis: Trellising is how a grapevine is trained to grow on wires and/or posts. There’s no “best” way to trellis a vine; each vineyard comes with its own requirements. A grape grower can use trellising to manage factors like sun exposure and vine vigor, and also to make harvesting easier.

TWO OF THE MANY WAYS TO TRELLIS A VINE

Green Harvest: Green harvesting, or “dropping fruit,” is most often used in the production of fine wines. Workers strategically cut off some of the tiny, immature grapes at the beginning of the growing season. This is costly, as less fruit always equals less wine, but a worthwhile investment. The vine inevitably focuses all of its energy on ripening and developing the flavor of the remaining grapes, whose quality rises dramatically as a result.

Organic: Organic wine, in its most broad sense, is wine made without synthetic chemicals: fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, or fungicides. Organic certification is complex and varies by country. The current U.S. certifications include the following.

100% Organic carries the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) organic seal and indicates the wine is made from 100 percent organically grown ingredients.

Organic also carries the USDA organic seal and indicates the wine has 95 percent organically grown ingredients.

Made with Organic Grapes or Made with Organic Ingredients means the wine is made from at least 70 percent organic ingredients. (It does not have the USDA organic seal.)

Biodynamic: Biodynamic farming principles are based on a concept originated by early-twentieth-century Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner. Beyond being 100 percent organic, biodynamic farming aims to balance nature, and views the vineyard as a cohesive, interconnected ecosystem. There is a mystical, spiritual aspect to this type of farming as well, which believers swear by and critics lampoon. For example, biodynamic grape growers plant, prune, and treat vineyards according to the cycle of the moon, and utilize a number of strange-sounding but effective “preparations” to invigorate the vineyard. (Preparation 500—cow manure—is buried in cow horns in the soil during the winter. The horn is then dug up and its contents stirred in water and sprayed on the soil.)

Diurnal: In very warm winegrowing regions (most of California comes to mind), grapes love the roller-coaster ride of a strong diurnal shift. Diurnal (dye-UR-nal) shift is fancy talk for the up and down of temperatures from day to night. If you’ve ever visited the San Francisco Bay Area you’ve felt this rapid transition firsthand—you can be downright hot during the day, but still have to pull out your sweater for the chilly evening. On any given day, the temperature range can vary as much as 20 to 30 degrees! In regions like Napa and Sonoma, the diurnal shift helps grapes retain their bright acidity over the growing season. It also ensures a longer growing season, which results in more developed flavor maturity.

Cool, wet winter provides ample groundwater

Lack of rain or frost after the first warm days of spring

Mild days and cool nights all summer long

Warm, dry days preceding harvest