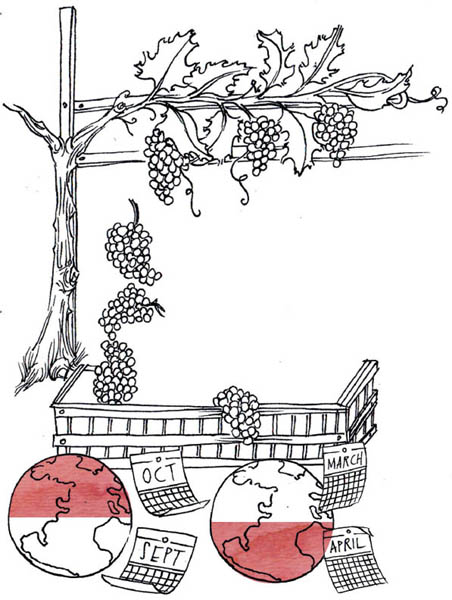

Temperatures rise in early spring (approximately February for the Northern Hemisphere and August in the Southern Hemisphere). When they hit about 50 degrees Fahrenheit, sap begins to concentrate where the canes were pruned. This leaking of sap, called weeping, is the first signal that the vine is waking up after a long winter sleep.

Twenty to thirty days after the vine begins weeping (typically March to April in the Northern Hemisphere and September to October in the Southern Hemisphere), tiny buds on the vine start to swell and open. This is commonly known as bud break. It is a joyous albeit tense time for vintners. Late spring frosts can be devastating, killing the tender baby buds, and thus the potential of the harvest, in a single evening.

In mid-April (in the Northern Hemisphere) and mid-October (in the Southern Hemisphere), shoots, leaves, and eventually teeny green clusters begin to emerge on the vine.

The vine continues to grow. About eight weeks after bud break those green clusters form flowers, which, after blooming, eventually become grapes. Flowering lasts only about ten days, but it is an extremely sensitive time in the vine’s life cycle. Climactic conditions like frost, heat, wind, and rain can wreak havoc on the delicate flowers.

From June to July in the Northern Hemisphere and December to January in the Southern Hemisphere, each fertilized flower develops into a grape. If desired, weeding, spraying for pests and diseases, and summer pruning (see “Green Harvest,” page 46) all happen during this time, as the grapes continue to mature.

Sometime around August in the Northern Hemisphere and January in the Southern Hemisphere, the grapes finally plump up and change color from green to yellowish white (grapes destined to make white wines) or black (grapes that will make red wine). This is known as veraison. During veraison, the vineyard workers sometimes prune some of the leaves around the grapes (to increase the circulation of air, thus reducing rot) and also continue green harvesting. Prior to veraison, the grapes still taste sour and are immature; but once it begins, sugars in the grape start to rise dramatically.

Traditionally, harvest occurs about one hundred days after flowering (August to October in the Northern Hemisphere, February to March in the Southern Hemisphere), but many factors are considered—especially the sugar and acid levels of grape samples, and the tannin maturity. White grapes are generally harvested before black ones to help retain higher acidity in white wines. Grapes are picked by hand or by a machine. Handpicking is more expensive, but is considered superior because it is gentler and more accurate. Also, occasionally it’s the only option (e.g., if your vineyard is on a steep slope).

After harvest, leaves turn yellow and fall off, and the vine is pruned. Pruning helps protect the vine from cold winter temperatures and also ensures that it saves as much energy as possible while in the dormant phase. How a vine is pruned, in part, determines how it will come back to life in the spring.

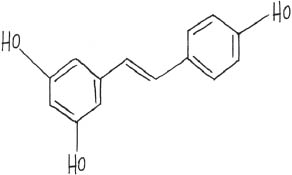

There has been a lot of buzz in the last decade about wine’s health benefits. One of the most studied, potentially happy-health compounds in wine is a powerful antioxidant called resveratrol (rez-VARE-ah-trahl). Although human studies are still in their infancy, scientists have done extensive animal testing and are claiming that resveratrol can significantly reduce heart disease, lower the risk of Alzheimer’s, and help regulate cholesterol, and has anti-cancer and even antiaging properties.

Once resveratrol was isolated, Cornell researcher Leroy Creasy decided to compare resveratrol levels in different wines, in an attempt to better understand how and why the compound is produced. After sampling dozens of wines from all over the planet, he made a couple of discoveries. First, across the board, resveratrol levels were highest in red wines. This is logical: antioxidants are found in grape skins, and red wines spend much more time in contact with their skins during the winemaking process than white wines do (more on that in a minute). Secondly, and more curiously to Creasy—pinot noir, and specifically Oregon pinot noir—had much higher levels of resveratrol than other wines.

What’s the magic resveratrol recipe? It turns out resveratrol is produced by plants protecting themselves against environmental dangers—most commonly pathogenic organisms, temperature extremes, and fungi. Pinot noir is a temperamental, thin-skinned grape that tends to thrive in cool, damp climates (where these dangers are more common). Therefore, pinot noir grown in the extremely moist climate of Oregon’s Willamette Valley has to produce loads of resveratrol just to survive. It seems the grape’s natural life-saving defense could end up saving human lives as well. I’ll drink to that!

My Favorite Oregon Pinot Noir Producers

Adelsheim

Adelsheim Bergstrom

Bergstrom Bethel Heights

Bethel Heights Domaine Drouhin

Domaine Drouhin Domaine Serene

Domaine Serene St. Innocent

St. Innocent Soter

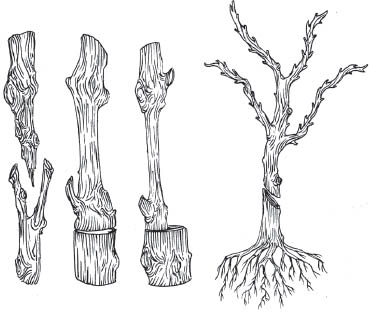

SoterIn the history of wine, one vineyard pest has proven more vicious than any other—Phylloxera vastatrix, alias “the Devastator.”

This tiny vampire aphid, native to the United States, first began its course of destruction when it hitched an unwelcome ride to France in the mid-1800s on some American grapevines. At that time, both America and France were experimenting with crossbreeding different species of grapevines to improve characteristics like vine vigor, flavor, and color. French winemakers were eager to study the American vines. They had no idea what was coming. In 1865, the first American vines arrived in Bordeaux and were promptly planted. Two years later, vines in this prestigious region started to get sick with an unknown disease, and many died. The mysterious ailment spread quickly; within a decade, a reported two-thirds of all French vines had completely vanished. Scientists were baffled, and the French government even offered a reward (the equivalent of about $1.5 million today) to anyone who could figure out what was killing their vines, and how to stop it.

Eventually, the root louse was identified as the culprit, and an American came up with the solution: to graft, or attach, European vines to American (phylloxera-resistant) rootstock. This simple fix sounded crazy, but it actually worked. Today, almost all the fine wine vineyards in the world are planted with American rootstocks on the bottom and European grapevines on top (illustrated below).

Did You Know? Besides disease and insects, some of the most destructive vineyard pests include deer, birds, wild hogs, wild turkeys, and kangaroos.

A season in the vineyard is over. Vines have done their work and the precious fruit has been harvested. Now the process of winemaking (or vinification) begins. Although there are many different schools of thought on how to best convert grapes into wine (many of these philosophies are region- or grape-specific), there are basic stages that all wine must go through in order to be born. Here are the most essential.

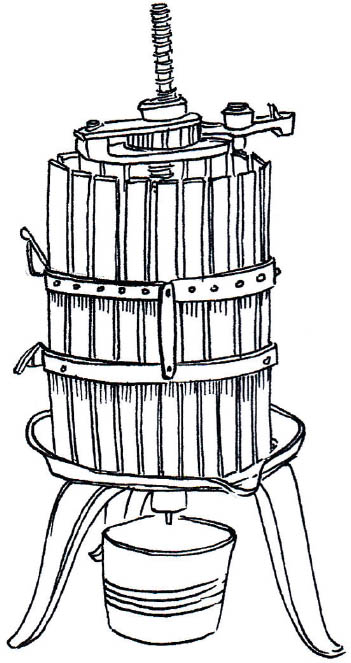

Juice is extracted from the grapes. Free-run juice is the coveted liquid that literally drips out of the ripe grapes before any crushing begins. Some wineries may use free-run juice to make a separate, extra-fine bottling, but most of the time it is just mixed in with subsequent pressings. The grapes are crushed (a.k.a. pressed) so that the liquid nectar can be separated from the skins, seeds, stems, and other stuff (see “MOG,” following). Ages ago, people used their feet to press the grapes. Now, winemakers use a variety of less romantic but more efficient (and sanitary) machines.

Skins are removed from white wines immediately to ensure a clear, bright color. Skins are left in contact with the juice of red wines; prolonged exposure provides color, flavor, and tannin. Red grapes with thick skin and/ or small berries will have a higher ratio of juice to skin during this process, which will mean more color, flavor, and tannin in the finished wine.

Petite sirah is an example of a very thick-skinned grape with small berries. If you’re a petite sirah fan you already know that this grape packs loads of big jammy fruit flavor, a ton of mouth-drying tannins, and enough color to turn your teeth a bright bluish purple.

Once the juice has been pressed, it is allowed to come in contact with yeast. Yeasts are like little ravenous monsters, chomping up the natural sugar in the grape juice and leaving the by-products of alcohol and carbon dioxide. In the old days, everybody just waited for naturally occurring yeast in the air to begin eating the sugar in the juice. These days, we’re not so patient. Many winemakers intervene by adding yeast strains that jump-start and move the fermentation along. Fermentation typically takes place in stainless-steel tanks, where temperature (and thus the speed of fermentation) can be monitored and controlled, or oak barrels, which impart flavor and texture to both white and red wines.

Did You Know? With only a couple of obscure exceptions, all red grapes produce white juice. The color in red wine comes from contact with the skins.

A final, and optional, winemaking step is aging the wine—in or out of oak barrels—before release. Aging usually lasts anywhere from six months to two years, although some fine wines age longer than that. In Europe, the length that fine wines are aged is mandated; in most other areas it is not. Aging in stainless steel is neutral—it gives nothing to the wine, except a place to hang out and get a little more complex and integrated before it’s bottled. (Like lasagna or beef stew, most wines taste better when flavors have a chance to meld.) Oak aging, however, can play a considerable role in how a wine tastes and feels; it can add tannin and a textural creaminess, and also impart aromas and flavors like toast, nuts, vanilla, butterscotch, caramel, nutmeg, cinnamon, smoke, and coconut.

There are many choices when it comes to oak barrels. First there’s the origin of the oak, which, believe it or not, plays a huge role in the flavor. For example, American oak is less expensive but more porous. It adds an aggressive oak taste (and often the telltale aromas of dill pickle and coconut!). French oak is generally preferred for its tight grain and, thus, more subtle, slow integration of oak flavor (more like butterscotch and vanilla). It is also much more expensive. The second choice is the age of the wood. New oak barrels give a more prominent flavor than oak that is a year or two old. Last, there’s the option to char (or toast) the inside of the oak staves, and if so, how much. Winemakers can specify that they want a light toast, medium toast, or heavy toast to their barrels; the heavier the toast, the more dominant the flavor of the barrel will be.

Additionally, winemakers may opt to age a wine on the lees—in contact with the dead yeast cells leftover from fermentation. This practice, widely used in Champagne and chardonnay production, adds a creamy texture and aromas of freshly baked bread.

Did You Know? If you ever want to engage a winemaker, casually ask him which yeast strains he uses. His eyes will light up and a big geeky smile will appear. Don’t plan on going anywhere in a hurry. However glamorous their jobs may appear, all winemakers are science nerds at heart; they love to talk biochemistry.

PHASE ONE: CRUSH

Juice is extracted from the grapes. Free-run juice drips out of the ripe grapes.

The grapes are crushed (a.k.a. pressed) to separate the liquid from the skin, seeds, and stems.

PHASE TWO: FERMENTATION

Once the juice has been pressed, it comes in contact with yeast and fermentation begins. Fermentation typically takes place in stainless-steel tanks or oak barrels.

In both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, these are the most important regions of the planet for grape cultivation

the approximate number of vines that live on one acre of land

the minimum hours of sunshine required by any vine during the growing season

the approximate number of bonded wineries in California—about half of those produce less than 5,000 cases annually

the number of acres of cabernet sauvignon planted in California

the number of new wine labels (one winery can make multiple labels of wine) that were approved by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau in 2011

One wine that does no aging before its release is Beaujolais nouveau (bo-jho-LAY new-VO), from Beaujolais, France. Beaujolais nouveau is made from the gamay grape and is released just a few weeks after harvest—the third Thursday in November to be specific. It’s a fresh, fruity, and short-lived wine. It’s typically very inexpensive and is meant to be consumed immediately. Because of the unique way it’s made, typical aromas and flavors include raspberries, candied fruit, grapes, bubble gum, and banana.

The style, originally promoted by wine producer and marketing genius George Duboeuf as a way to create some buzz and generate cash flow, became wildly popular in the 1970s; Beaujolais producers would literally race to Paris with fresh juice (and a great excuse to drink!). The party spread to other European countries, and then America, where it was adopted as a traditional Thanksgiving wine. Over the years, and with so many other choices available, the hype and demand of Beaujolais nouveau has shriveled. It’s still worth drinking, and as long as you keep your expectations low, you’ll likely enjoy the fresh fruitiness of nouveau. Just remember to buy the current year’s release, chill it, and drink it within a few weeks.

Because of Beaujolais nouveau’s popularity, most people only think of these supercheap, quaffable wines when they think of Beaujolais, and thus pooh-pooh any mention of the region. But, one of wine’s best kept secrets is cru Beaujolais. There are ten superior wine-producing Beaujolais towns, called crus. They are capable of producing some surprisingly beautiful, graceful wines that can have the sensual aromatics and supple texture of pinot noir from northern neighbor Burgundy, at a fraction of the price. If you love earthy wines, ask your favorite wine retailer for its best cru Beaujolais wines. I think you’ll find their taste, and their price (usually fifteen to twenty dollars), refreshingly delightful.

Did You Know? Oak barrels are a major expense for wineries. If you are drinking a ten-dollar bottle of chardonnay that brags about oak flavors on the back label, chances are it didn’t come from a barrel. There are several far less expensive—but far inferior—ways to impart an oaky aroma, namely dipping “tea bags” of oak chips in large vats of wine. Often, this type of oak flavor can come off as coarse, harsh, or out of balance with the rest of the flavors in the wine.

Besides the grape variety, the most important factor in how a wine will taste is the environment it grows up in—its terroir. There is no direct English equivalent for terroir, the fancy French word that you are certain to hear time and time again in wine circles. It’s pronounced “tare-WAH.” Go ahead. Practice saying it. Tare-WAHHHH. Many people mistakenly oversimplify terroir, and think of it as soil. It is so much more.

Terroir is the essence of a particular place. As it applies to a grapevine, terroir encompasses the soil, subsoil, aspect, slope, nuances of weather, orientation to the sun, the ocean, the river, humidity, neighboring plant species, elevation, and, ultimately, human intervention. Each vineyard—each grapevine—is said to have its own unique terroir, which is ideally recognized and appreciated in the finished wine. Terroir is ultimately what makes pinot noir from Germany taste different from the same grape grown in Sonoma, California. As with human development, the impact of environment can be even more influential than genetics.

The French may have been the first to coin the term, but terroir is no new concept. From the very first Greek and Roman vintners to Eskimo fisherman and ancient Chinese rice farmers, humans have always been innately programmed to identify, gravitate toward, and then dissect specific places that produce exceptional food. Georgia’s Vidalia onions taste sweeter than onions from a neighboring state. Florida oranges are the juiciest. Coffee beans planted in the shaded mountains of Colombia are especially rich in flavor. Fresh yellow corn from Farmer Ned’s patch bursts with just a bit more bright, corny flavor than Farmer Joe’s next door. The list of examples could go on and on.

As intangible as it is, terroir is real. Ancient winemakers embraced it. Modern wine-making has used science to try to outthink it. But, today, thoughtful wine farmers everywhere agree: Terroir is what gives a wine its soul, and it cannot be concocted, no matter how hard we try. Terroir is nature’s magic.

Whether you’re talking to a Buddhist monk or a solicitous winemaker, one universal truth is clear: A little suffering is good for everyone. A life without challenge is a half-life, and only through enduring adversity is one presented with the opportunity to fulfill the depth of their capacity for truly being alive. Suffering might be an uncomfortable subject, but I doubt you could find many who didn’t regard some sort of suffering as an integral part of the formation of their character. Often the most interesting and evolved people are those who have managed to persevere—and surprisingly to thrive—through hardships. In short, suffering is good for us. It produces strength, resiliency, and character. Incredibly, it is the same with grapes.

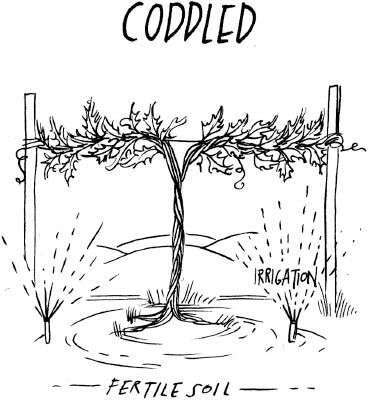

Unlike most plants, grapes are human-like when it comes to character development. Grapes that are given everything they ever want and need grow up fat and lazy. The resulting wines lack character and depth. The finest wines are made from grapes that struggle.

The coddled vine results in megagrowth— big fat grapes and lots of them. More grapes per acre is always better for profit, so large wine companies work their vineyards like factories, pumping out the most volume possible. There is a consequence; wines made from coddled grapevines are generally watery, flat, and lacking in character. Many times these wines taste so boring that the wine scientists feel the need to add chemicals to boost flavor. Additionally, since the coddled grapevine does not have to dig deep to find water or nutrients, its root system is thin and shallow, and it is utterly dependent on receiving these things from humans, forever.

In contrast, the vine that struggles produces much less fruit. Take, for example, that some of California’s most prolific vineyards are producing more than ten tons of grapes per acre, while some of its highest-quality vineyards produce a scant one ton or less per acre. Not only are there far less grapes as a result of struggling vines, but these survivor grapes are much smaller in comparison. The vines dig deep into the soil to find water and nutrients. They develop an extensive root system, allowing them to tap into the complex, natural mineral flavors of the earth and giving them a natural resiliency in times of drought. Struggling vines are stronger, more independent, and produce profoundly better quality and more interesting grapes, which in turn, make for better wine.