The accident had happened on the main road, a mile from my mum and dad’s house: a road that, even on my mum’s most worried nights, calling Floyd’s name into the silent air, she had never imagined he ventured as far as. My dad had been driving back from the swimming pool. He would have been having his usual fun there: hiding his friend Malcolm’s shoes for a laugh in the changing room, and exchanging stories with the other regular swimmers, such as Danny, who’d once climbed up a ladder and mimed an obscene act with a billboard advert of Kylie Minogue. As he began to signal for the turning into the village, my dad spotted a lump of white and black fur in the road and, instantly, he’d known. ‘But are you sure?’ my mum had asked him when he’d arrived home and told her. ‘Are you sure you saw enough to be sure?’ Then, when he’d assured her, and she’d asked him again, and he’d reassured her again, he’d collected a fluorescent jacket and driven back to pick up Floyd’s body – a perilous task in itself, on a single-carriageway road that dickwitted trainee Jeremy Clarksons routinely drove along at 90 mph, where an average of one fatality per year had been recorded in the decade and a half my parents had lived near it. I could picture precisely how solid and calm my dad would have been during all this. He could sometimes turn a non-crisis into a crisis, but the positive flipside of that was that when it came to an actual crisis, he was a rock.

I experienced a new emotion in the weeks that followed. I had been an adult long enough to be aware of my parents’ vulnerability, to join with them in their own sadnesses and disappointments, but now something different happened: I ached on their behalf. Ached in a way that, every time I spoke to them on the phone, created a painful hollow an inch or two below my breastbone. I’d loved Floyd; over the last couple of years, his ebullient presence had made me look forward to my visits to Nottinghamshire in a whole new way. But my own feelings about him were comprehensively drowned by sympathy for what my parents were going through. After the death of their previous cat, Daisy, they’d gone five catless years – an extremely ‘un-them’ period. They made their excuses: they were enjoying living in a cleaner house; they wanted to be able to go on holiday without the worry of what to do with a pet while they were away. But I knew that their hesitation about plunging back into cat ownership was ultimately down to another reason that made a lot of people hesitate about adopting a pet: the knowledge of the fragility of an animal’s life, and the heartbreak you open yourself up to when you make yourself responsible for that life. When they had finally caved in, they’d embraced cat ownership like never before, partly because, as a retiree and a homeworker, they had the time to do so in a way they hadn’t in the past as two full-time schoolteachers, but also perhaps partly because in that catless period, a reserve of love had built up which could not help but burst forth and overflow. And also, finally, because Floyd was an easy cat to love: a small but excitable presence whose energy had become part of them. The cliché that his death had left a big gap in their house applied, but it was more than that. Their house now was the gap.

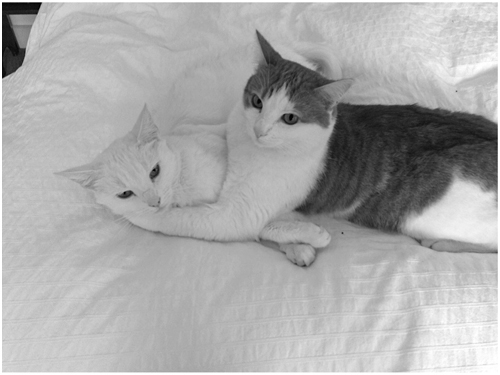

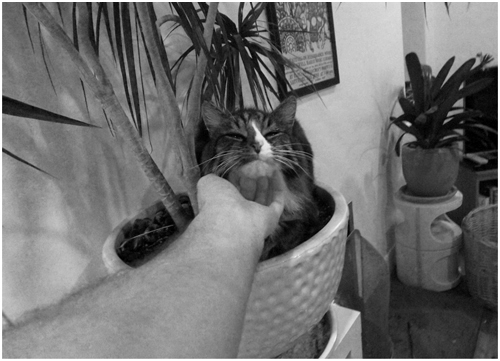

Of course, in the days after Floyd’s accident I cuddled my cats harder than ever. ‘OK, what have you done?’ their eyes said. ‘And should we be worried?’ I was now into my fourteenth year of living with Ralph, Shipley and The Bear. I had been immensely lucky that each of them was a strong, healthy cat, and lucky too, perhaps, that they lacked (or, in The Bear’s case, had long ago grown out of) the kind of wild wandering streak that Floyd had possessed. I’d lived alongside each of them for so long, their habits seemed almost an extension of my own. Here was me, going to the fridge to get a cold pickled onion to eat, and here was Shipley, going to the fridge to climb up my leg in case I happened to get him a small chunk of turkey from a packet on the same shelf as the pickled onions. Here was me, putting on a BBC4 nature documentary and here was The Bear, sitting six inches away from my face, staring at me in a haunting, accusatory way as I watched footage of foxes mating. Here was me, going into the living room and putting on a record, and here was Ralph, following me into the living room, jumping on the sleeve of the record and knocking it onto the floor. They were all familiar actions that took place in my immediate periphery, and innate parts of what I was as a quotidian domestic being.

But this scenario wasn’t going to be familiar for ever. Each of these three cats could now officially be classified as ‘old’ in cat years, and, in The Bear’s case, more or less geriatric. If I hadn’t already realised it, I would now, due to the ever-increasing number of strangers who reminded me of it on The Bear’s densely populated Facebook page; nomads of the Internet who, though they’d never read my books about him, felt it their duty to stop by and inform me of his imminent demise. ‘Your cat is very old now,’ they told me in thoughtfully composed messages from Perth and Wrexham and and Sioux City, Iowa. ‘I hope you know that it will soon be time, and you’ve prepared yourself.’ Perhaps they took me for a not very bright person who was under the misapprehension that cats live as long as humans. I was very aware of The Bear’s mortality, which was why I tried to fend it off every day by feeding him extra treats, repeatedly reminding him that I loved him and stroking him in that particular part of his chest that made him do an ecstatic tweet-purr. But the prospect of losing a cat who had lived a remarkably long, happy life could not be compared with the concept of losing a cat who was at life’s zestful beginning.

Floyd’s death seemed to trigger a period of unhappy events in the immediate area surrounding my mum and dad’s house. Less than a day after they’d buried him, their next-door neighbour Edna, a good friend of theirs who had been a botanically inclined maternal figure to my mum since the death of my plant-loving nan five years earlier, died of a heart attack. Only four days after that, their nonagenarian neighbour on the other side, Bea, finally succumbed after a long illness. An eerie silence accompanied my mum and dad’s forays into the garden.

‘How are you?’ I asked my dad. ‘I’m OK,’ he replied. ‘Just sad. It hurts, but I know he had the best life possible.’ I needed less than a hand’s worth of fingers to count the amount of times in my life I’d heard him speak so softly.

‘I keep remembering the way he’d jump on me when I was asleep in the garden, or pinch my office chair when I nipped out of the room.’

At night, my mum dreamt about little else but Floyd: sometimes the dreams were so real she would wake up feeling sure he’d walked in and been on the bed, the memory of his rain-wet fur palpable on her hands.

I wanted to drive to Nottinghamshire and whisk the two of them back here to Devon – if not for good, then at least for a fortnight, to ease their minds, to rid them at least temporarily of the constant reminders they were living with. He had been such a part of their life – sneaking into their car, sleeping in their waste-paper baskets, climbing ladders with my dad while he cleaned the windows – that every part of their house creaked eerily with his non-presence. Then on top of that, there was the difficult job of shutting out the brutality of his demise. You didn’t want to think about it, but a glitch in your brain steered you back to it, told you that recognising it was something you needed to do, out of respect for him.

So much of human happiness was about this, wasn’t it? How much you chose to shut out. How much of the bloodshed and war and cruelty out there in the world you let in through the portholes of your mind. How much you patted yourself on the back for saving a spider from drowning in the bath, while being unaware of the other three you potentially trod on earlier outside. How much you admitted to yourself the reality of all the deeply adored pet cats around the country who had been run over today, this month, this year. Shutting stuff out can be a bad habit, a selfish habit, an apathetic habit, but at times it’s how we survive, especially in our new world, where every atrocity is there to see at the click of a mouse. I shut stuff out every day. If I didn’t, I’d probably spend my life like The Bear, walking around, looking deep and aghast into the eyes of everyone I met, communicating in ghostly meeoops.

In the end, all you can do is carry on, clinging to that repeated, redemptive cliché of adult life: stuff almost always does get better. The key is time. Largely, as I got older, what I desired most in life was time – big chunks of it in which to write, to read, to walk, to feel free – but now I desired it in a different way; I just wanted a big chunk of it to pass, quickly, to take my parents to a point where they’d healed.

My mum, my dad, Gemma and me, all perhaps knew that there was a logical next step, cat-wise, but I wasn’t going to mention it first, and I thought it best that it didn’t happen until that time had passed.

In the event, it was my mum who brought it up. ‘We should probably take George now, shouldn’t we?’ she said. ‘It would make sense.’

I hemmed and hawed and made attempts to stall her, giving my reasons – my own attachment to George, and my hope that it might still work out between him and Roscoe – but, while there was a fragment of truth to these, I had an ulterior motive: I wanted to wait until my parents had grieved a little longer and were ready. I remembered from my childhood what it was like to lose a young cat suddenly in tragic circumstances and replace him rashly with another. It was not necessarily a bad thing – you were, in the end, filling an empty space with an animal’s life that you hoped to quickly make better – but it could stir up a small, confusing emotional dust storm and cause a brief, acrid taste of disloyalty.

My first Devon summer had come to an end, an idyllic summer I’d spent most of somehow feeling healthier than ever and fairly seriously ill at the same time; simultaneously ecstatic at being free to be outdoors in such an amazing place, and chained to the neuroses and needs of a handful of animals which, in the loosest sense, I owned and a few others I didn’t. Now autumn was coming in with a capricious vengeance uniquely characteristic of the area’s microclimate. In driving evening rain its leaves advanced on the house, their damp, recently deceased faces pressed against the windows like a leaf version of Night of the Living Dead. I was standing in the kitchen during one especially stormy dusk in October when I saw Shipley fly past the window backwards. I might have worried more, but this sort of thing happened to Shipley quite a lot. He was wiry and immovable in some ways – especially if the promise of turkey was in the air – but with age he’d become prone to be whipped around in a strong breeze. In this way he was very different to his tabby brother, who could probably sit in one of his favoured ‘cat monorail’ poses in a strong hurricane and not even wobble.

I popped outside to check Shipley was OK. He looked a little dishevelled but appeared unharmed by his flight, and swear-meowed to confirm this fact. He should have considered himself lucky. Once you get past summer, the wind in Norfolk tends to have a vicious bite to it. In Devon the wind often pulls scarier faces, but it’s got false teeth. This was a hotter place than I’d ever lived in, but I could feel something bright and warm and magical being inched away from me, like a cake on a tablecloth slowly pulled by a mystery hand. On the plus side, we had re-entered the six months of the year when the whole county – including a large proportion of its inhabitants – smelt pleasantly of woodsmoke. In the big copse behind the house, and on my walks with Billy, I foraged eagerly for loose kindling, separating it into three grades and then pocketing it.

‘You know what you’ve become? You’ve become the bloke who has cat hair on his coat and a load of kindling sticking out of his pocket,’ said my friend Louise, as I came down the garden path towards her with cat hair on my coat and a load of kindling sticking out of my pocket.

Up in Nottinghamshire, my dad had an enviable relationship with the local farmer, which permitted him and his friend Philip to keep any firewood they found on the farmer’s land provided they chopped it up themselves. ‘PHILIP DOES THE CHAINSAWING,’ he told me. ‘I’M THE BRANCH MANAGER.’

This arrangement had led to a surprising number of adventures and feats of rural heroism. One of these involved my dad and Philip helping two young lovers narrowly escape from a herd of cows my dad estimated to be ‘BETWEEN EIGHTY AND A HUNDRED STRONG’. In a dramatic scene straight out of a James Herriot book, the young man had tripped over at the last minute, with the cows bearing down on him, only to be hoisted over the fence by Philip in the nick of time. More dramatic still had been an incident that my dad described to me on the phone.

‘I JUST FELL IN THE RIVER,’ he announced. ‘I FOUND THIS REALLY BRILLIANT LOG FOR FIREWOOD AND TRIED TO TOSS IT ACROSS THE RIVER LIKE A CABER BUT I SLIPPED AND IT DROPPED IN THE WATER AND THE FOOKIN’ CURRENT STARTED TAKING IT. BUT I RAN DOWN THE SIDE OF THE RIVER AFTER IT REALLY FAST AND CAUGHT IT UP ABOUT A HUNDRED YARDS AWAY AND MADE A GRAB FOR IT BUT THEN THE MUD SUCKED MY WELLIES OFF MY FEET.’

‘Oh no!’ I said. ‘Then what happened?’

‘THEN I FELL IN AND GOT MUD AND RIVER WATER ALL OVER MY BEST SOCKS AND NEW GLASSES. I GOT THE FOOKIN’ LOG, THOUGH, AND BROUGHT IT BACK. THAT’S THE MAIN THING.’

I was glad to hear my dad sounding chirpier and louder than he had recently. Along with going to Derbyshire with my mum and retracing some of the walks we’d done there as a family in the 1970s and 1980s, chopping logs had been one of the activities that had best helped take his mind off Floyd. It had always been one of his favourite hobbies. Traditionally, if I arrived at my parents’ house and didn’t immediately see my dad in the driveway with his shirt off, chopping wood, it meant one of three things: he was taking a nap, one of the weathermen he liked to shout at was on TV at the time or dusk had fallen more than an hour before.

All of my male relatives within living memory on my dad’s side of the family have possessed very loud voices and been enthusiastic about firewood. I represent a slight dilution of the bloodline, in that I am enthusiastic about firewood but only possess a voice of moderate volume. One of my dad’s loud cousin Flob’s first memories of my grandad was of him and my great-grandad carrying a giant, two-man saw along their street in Nottingham, shouting excitedly, having heard a rumour that an oak had come down at a nearby farm belonging to a man called Tommy Thompson. Later, my grandad would lead my dad and Flob and the other kids in their neighbourhood on expeditions to retrieve logs from the nearby woods. My dad and Flob’s teenage gang spent the coldest British month of the twentieth century, January 1963, using their spoils to make fires on the frozen canal up the road.

You can run from this kind of genetic destiny but you can only hide for so long. A decade ago in Norfolk, I’d had the Upside Down House’s chimney removed: a structurally necessary, refurbishment-related decision, but one that now seems an absurd denial of what I inescapably am as a human. As I moved further into my thirties, I began to take more and more pride in my own garden bonfires, go on detours on walks solely to sniff those belonging to others, and to look at the process of felling trees in my garden almost as a form of meditation. I’d finally arrived at my current state as one of those bearded men you frequently come across in the West Country who smell of woodsmoke and start conversations about lichen in their local pub. Recently I’d even completed a forestry skills course, and proudly displayed my certificate from it on my office wall. I had cats, too, and all cats deserved a log fire, if you could possibly provide one for them. I was especially looking forward to Ralph and The Bear’s resurgence as fire cats, sprawling out in front of the flames as they had done here back in early spring.

‘I’VE GOT TWO THINGS TO SAY,’ my dad told me. ‘FIRST THING: I’M GLAD YOU GOT YOUR HAIR CUT. YOU LOOKED SHIFTY BEFORE. I CAN ALMOST TAKE YOU SERIOUSLY NOW. SECOND THING: YOU’RE GOING TO FREEZE YOUR FOOKIN’ KNACKERS OFF THIS WINTER IF YOU DON’T HAVE SOME OF MY LOGS.’

He had a point: Devon might have had big-talking, toothless winds, but winter was on its way and our cottage was high on an exposed hillside; the logs I’d bought in bulk back in March had almost run out, and the ones sold by the nearest petrol station burned so poorly I’d have done no worse trying to find a sustainable heat source from a dozen Eccles cakes. But I knew that my dad was proprietorial about his firewood and I sensed, rightly, that there would be a catch.

‘IT WILL WORK LIKE THIS,’ he said. ‘I’LL GIVE YOU A FOOKLOAD OF LOGS AND YOU GIVE US YOUR CAT IN EXCHANGE.’

I’d done some swaps in the past that might have been viewed as lopsided: a 1960s dining table for three albums by the agrarian folk musician Dick Gaughan; a Panini football sticker featuring the face of the explosive and stylish Aston Villa winger Mark Walters for one featuring that of the unexciting Chelsea midfielder Nigel Spackman. But this was the first time I’d been asked to exchange a cherished living pet for a few bags crammed full of dead tree. My parents would undoubtedly be getting the better deal here. In a couple of months’ time, the logs would have run out, but George almost certainly would not. He’d still be there, providing another kind of warmth with his sunny disposition. I already envied their place in his company.

The timing was good in an additional way: ‘I think we’ve got mice living under the sofa,’ my mum had told me recently. ‘They’ve stolen the chocolate your dad likes to keep under there.’

As I took my final few Devonian evening walks with George along the stream behind the cottage, I was struck again by what a unique bond the two of us had. In a way, we’d spent 2014 going in opposite directions – me rewilding, him dewilding – but we found ourselves in a similar place. He got on well enough with Gemma, but it felt like he knew I’d been the one responsible for turning his life around. He wanted to be with me all the time: not in a nagging or a dominant way, or even a particularly food-themed way, just in a calm way. Forsaking our life together was something he might never forgive me for, but what else could I do? Keeping him here would have been a hugely selfish gesture on my part. It would not have been fair to Roscoe, to Gemma, to my parents or to Ralph and Shipley.

A giant full moon hung over the house on the evening my parents arrived to collect him, the kind of moon that lights up the bedroom at night and makes you think it’s dawn when it’s really 2 a.m. Devon had these big moons a lot – somehow bolder and less neurotic than the moons you found hanging about in other parts of the country – but this was probably the biggest I’d seen since the day we moved in. I thought back to that night, and the shape that darted across the lane behind me, and there seemed something poetic about the way these two moons book-ended George’s stay with us. The second moon’s light played on the coppery leaves behind the house and twinkled on the stream: George’s kingdom. This terrain, this whole region of the country, was so inimitably George, I could barely imagine it without him. I reminded myself that he was a cat, and no great connoisseur of rural eccentricity; any nice bit of countryside was the same to him. It wasn’t as if he was going to get to the fields around my mum and dad’s house in Nottinghamshire and say, ‘It’s just not the same without a woman in a smock playing a flute in the meadow behind your garden and a man walking an owl nearby.’

Or was he?

* * *

My dad had not been joking about the logs. Pile upon pile of them filled my parents’ hatchback. When I thought he and I had finally brought them all in and stacked them in the porch, he arrived up the path with a large cat carrier. This, too, was full of logs.

‘RIGHT,’ he said, flopping down on the sofa. ‘CAN YOU PUT ROLLING NEWS ON THE TELLY FOR ME? I’VE BEEN UP SINCE FIVE AND WE’VE BEEN TO THE BEACH. I’VE GOT THAT BOOK I BORROWED OFF YOU IN MY BAG. THE ONE ABOUT THE BLOKE WITH THE BIT IN IT WITH THE GOOSE. IS THAT YOURS? WELL, ANYWAY, EVEN IF IT’S NOT, IT’S GOT CHOCOLATE ON IT NOW. WHAT WE’LL DO IS GET UP REALLY EARLY TOMORROW THEN WE’LL GET THE CAT AND GO.’

‘Calm down, Mick,’ said my mum. ‘We’ve only just got here. And there are some gardens and an exhibition I’d thought I’d quite like to go and look at tomorrow.’

‘I’M JUST BEING ORGANISED,’ said my dad. ‘SOMEONE HAS TO BE ORGANISED. WITHOUT MY ORGANISATION AND ALACRITY THIS FAMILY WOULD FALL TO BITS. AND WE CAN’T LEAVE TOO LATE BECAUSE OF THE TRAFFIC. IT’S A THURSDAY, SO THE FOOKWITS AND LOONIES WILL ALL BE OUT.’

‘Why will they be out on a Thursday, in particular?’ I asked.

‘THURSDAY IS THE NEW FRIDAY. HAVEN’T YOU HEARD?’

I looked at George, upside down on the sofa, paws splayed, and wondered if he was ready for the tornado he was about to go and live inside. Of course, he’d spent a few days at my mum and dad’s house before, but he probably just remembered that as a brief, somewhat traumatic holiday. Encountering my dad’s loud jazz music and equally loud, lengthy anecdotes about his cousin Flob and tirades about Jeremy Clarkson and Alan Titchmarsh on a full-time basis was another matter entirely. I could only be thankful that he was a relatively unflappable cat, not known to be fazed by Miles Davis’s more experimental late 1960s period or sudden, vociferous non sequiturs about celebrities.

‘HAVE YOU STILL GOT THOSE WEIRD SEX LADYBIRDS?’ asked my dad.

‘Yep, they’re still here,’ I said.

That month, our local Devon newspaper had reported that a swarm of harlequin ladybirds had landed in Plymouth from America, a sort of seedier, reverse ladybird version of the maiden voyage of the Pilgrim Fathers on the Mayflower in 1609. On top of the fact that these harlequins were already responsible for ruining the clean washing of many of the city’s suburban households, it was also thought that a lot of them carried Laboulbeniales fungal disease, a known STD. I couldn’t be sure if the gangs of ladybirds currently congregating twenty miles east of Plymouth, on our living room door frame and bathroom window ledge, were the same ladybirds, but I was giving them a wide berth.

‘I CAN’T STAND THAT GEORGE CLOONEY,’ my dad went on, gesturing at the TV, which showed George Clooney standing outside an awards ceremony, smiling at his fans and the media.

Clooney’s smile was not unlike that of the other George in the room: infectious, beatific. ‘What did he ever do to you?’ I asked my dad.

‘HE’S IN LOVE WITH HIMSELF,’ he said. ‘HE’S WHAT WE USED TO CALL A BIGHEAD IN THE OLD DAYS. NOBODY USES THE WORD “BIGHEAD” NOWADAYS BECAUSE IT’S OK TO BE ONE.’

‘But he’s George Clooney. I think really … Shipley! Stop that!’

As we talked, Shipley, in the far corner of the room, had been attacking the waste-paper basket with a level of determination that made his morning bin-kicking sessions look casual. Now the bin tipped over and its contents spilled onto the living room floor.

‘OH, I KNOW WHY HE’S DOING THAT,’ said my dad. ‘I PUT A DEAD CRAB IN THERE EARLIER THAT I FOUND ON THE BEACH. I THOUGHT ABOUT KEEPING IT, BUT IT WASN’T A VERY GOOD ONE.’

As all this took place, The Bear watched from his new favourite vantage point: the final slot in the wooden unit where I kept my LPs. I knew how much he liked it in there, so I’d packed the albums in the other slots very tightly in order to keep it free for him, but there were some very good second-hand record shops in Devon and soon the inevitable overspill would take place, with the likes of Stevie Wonder, Neil Young and ZZ Top forcing The Bear out. No doubt he’d find another surveillance point soon enough, from where he could watch the absurd affairs of humans and mortal cats and make notes on them to take back eventually to his superior home planet. He’d become a little more zen and unflappable in the eight months since we’d moved here. There was a time when, with Shipley on one of his vandalistic rampages, The Bear would have quickly made himself scarce, but he seemed less fazed by them these days, or by Shipley in general.

I put this down partly to The Bear’s failing hearing. Living with Shipley – especially around mealtimes – was a lot like living with a large furry meatfly: much of the intimidation factor came from a constant, aggressive buzzing sound combined with insistent, restless movement. Once you took the noise away, there was a lot less to fear. When Shipley strutted in The Bear’s direction, The Bear now no longer heard his approach, so no longer shrank from it, and with this some of the joy seemed to go out of the chase for Shipley. The Bear would often not even realise he was being harassed until Shipley’s face appeared over his shoulder. ‘Oh! It’s you!’ The Bear seemed to say at these points: a little shocked, but without fear. A couple of minutes later, the two of them would be found sitting quite peacefully together, the poet and the fool of my medieval cat court, finally harmonious after years of rancour. It was a good lesson on the psychology of bullying; Shipley’s persistent, aggressive balloon had been popped solely by The Bear’s transcendental calm. That said, The Bear was still very protective about his Bearhole in the garden, and would issue a warning gargle if Shipley tried to join him in it.

I liked to think that The Bear’s growing serenity was also down to the time he’d spent with George recently. I’d found George backwards-spooning him again, and The Bear certainly didn’t look unhappy about it. Would he miss his idiot pal? Perhaps not. The following morning there were no choked-up goodbyes from The Bear as George’s carrier was brought into the living room. I was another matter entirely. It was my job to load George into his plastic travel prison because Gemma was at work by then and, well, ultimately, how could it be anyone else’s? I reminded myself that it could be worse: he could be going to live with a stranger, and I might never see him again. At least I had visitation rights. Who knows? Maybe one day he might even move back to Devon. But there was something very final about the moment when I locked the clasp on his carrier, something that made me realise I had never been fully committed to our previous goodbye. The simple, sad look on his face as he stared back at me through the bars, betrayed and uncomprehending, would stay with me for weeks.

About a month after George left, I took The Bear to see the vet. The lump on his back had returned, slightly bigger than before, and this time it didn’t mysteriously vanish when the vet examined it. The vet said it was a cyst, but nothing to worry about or that would require an operation. I wish I could have said the same for my own lump. Going to my own special human vet to have it removed had become such a regular occurrence for me that I’d started to view it as a little like having a haircut; the only real difference being that it happened more frequently and nobody asked me if I was going anywhere nice for my holidays this year. If my doctor had asked me if I’d been going anywhere nice for my holidays this year, I would have told him the truth, which was that I didn’t have proper holidays, due to the fact that I lived with four demanding cats. Three of them were getting on a bit now, but this most ancient of them was doing pretty well, to say the least. He’d lost a tiny bit of weight recently and his appetite had increased significantly, and the vet confirmed my suspicion that The Bear was suffering from a slightly overactive thyroid. This was normal for a cat in his twentieth year, and the vet and I agreed that, in view of his age and the level of the problem, it was best just to monitor it for now, rather than put The Bear through the stress of any of the treatments available.

I remembered four years ago when another of my cats, Janet, who’d been suffering from a much more extreme case of hyperthyroidism, had died very suddenly. In the aftermath of that, The Bear, the older of the two cats, had seemed to be the unlikely survivor. Since then people, whether strangers or friends, had warned me so often about his imminent demise. And now here he was, much older, the survivor again, with poorer hearing and less easily retractable claws, but other than that largely, astoundingly, the same: a cat who was precisely the age of the second Oasis album but to whom time had been far kinder. If I was honest with myself, a year ago, in that dark bungalow, surrounded by diesel fumes and the clang of skips, with Gymcat lurking outside, I could not have pictured The Bear here now, in this good place. In fact, it would have been quite a stretch to picture myself here, too. His hearing was definitely going, but it didn’t seem to be troubling him. If anything, the opposite was true: the main effects, as well as diminishing Shipley’s presence, were that he seemed amazingly pleased to see me or Gemma when we miraculously and soundlessly appeared beside him in the garden, and that his new friendly bee sound and sessions of meooping at his favourite water bowl became louder and more ebullient than ever. Sometimes, the love that he felt for his water bowl was so deep he’d curl up and sleep beside it on the bathroom floor. His affection for it was understandable. Devon, particularly the region around Dartmoor, does have some of the UK’s best water.

As winter came in hard, I fed The Bear more treats than ever: high-end tunas, chicken drumsticks, prawns. It was my way of keeping him happy, going by the philosophy that happiness creates longevity, but it was also my attempt to find ways to thank him. Over the last few years, I had come to view him as a lucky charm as well as a friend, a sort of watchful, furry warden of my life.

In less of a show of gratitude, I had finally filled the empty slot on the unit where I kept my LPs, edging The Bear out. At night, he and Ralph now curled up a few feet to the right of it next to the fire and, when I went to bed, I put an extra log on for them – partly out of kindness, but also because time has taught me that cats remember everything. Both of them had turned into ardent fire cats, a habit that pleased me immensely. Shipley, meanwhile, remained nervous around the hearth, and Roscoe preferred the softer warmth of a human midriff. At night, she burrowed fiercely into any available person. It took her a while to come fully back to us, and, weeks after George’s departure, she still looked anxiously over her shoulder every time she arrived in the kitchen doorway or by the sofa in the living room, George’s favoured ambush spots. From her point of view she probably could not believe he was gone because, by all cat logic, she could see no good reason why he would be gone. He wouldn’t just decide to leave, after all. He had it too good here. But by tiny increments, she withdrew her guard and let herself believe. Outdoors, she became confident more quickly, and transmogrified into the old Roscoe, smacking Shipley into line with one paw and getting on with hedgerow admin with another. She was a Diana Rigg of cats: dainty but menacing, although with a bit less of the dainty now that winter weight of hers was piling back on. As she followed me up through the skeletal, lichen-furred trees behind the garden to the waterlogged meadow, stripped of its flowers, I realised something about her battle with George: a big part of it might in fact have been territorial all along. The cat who owned this land was gone. Now she had moved in, unchallenged, and annexed the whole lot.

I’d been convinced that, once George had gone, another interloper would soon follow, but there’d been nothing. Two days after he’d left I’d noticed a flash of grey behind the garden fence and thought it was the return of Fluffy Grey Poo Burglar Cat, but it had just been a squirrel. Almost as far back as I could remember there had been an outsider cat – usually homeless, sometimes just downright obnoxious – trying to muscle in on my cats’ party, but now a rare period free of invasion began, and its effects showed. Each of them became bigger versions of themselves. I realised, really realised, for the first time how truly subdued Ralph and Shipley had been during George’s tenure here. Mostly, Gemma and I were happy to have them 100 per cent back with us, but there were times – those, for example, when Shipley stole some toast or clawed his way swearing up the back of the chair I was sitting on, or when Ralph walked about the house at 4 a.m. pulling stuff off shelves, meowing his own name and sitting in plant pots – when we felt more conflicted about it.

My mum had always felt that my attempt to make George part of our household was a mistake, but she knew what a wrench it was for me to let go of him and her updates about his new life in Nottinghamshire came thick and fast. The one early bump in his progress was Bonfire Night, during which he hid under their spare bed. This was in sharp contrast to Shipley, who, at the first sign of fireworks had walked outside, more or less held his paws out wide to the night air and defiantly announced, ‘Bring it.’ Fireworks, it transpired, were George’s one other fear besides the cupboard under the stairs in his old home. My dad’s booming voice and 1960s African pop albums and loud footsteps, Sooty the local delinquent cat from three doors away, the thug hedgehogs who’d attacked my mum’s slippers, the cows in the field behind the garden – none of these things held any trepidation for him. As for Casper, their friendship took no time at all to develop and, while not without its rough and tumble aspect, left Casper slightly less dishevelled than his relationship with George’s predecessor.

‘George and Casper talk to each other a lot,’ my mum told me. ‘They do this wibbling thing at one another. Then, if they’re tired, they’ll sometimes go up to the bed and sleep next to one another. George has this new noise, too, kind of like a quiet cockerel.’

I felt torn, hearing this news. I was relieved George was settling in well. On the other hand, what exactly was this quiet cockerel noise, and why hadn’t he made it for me? Perhaps he reserved his quiet cockerel noise solely for people he truly loved. Maybe, in fact, what the quiet cockerel noise meant was: ‘I prefer you to the heartless Tom, who so coldly gave me away, after everything he and I had been through.’

My parents had both had a strong relationship with Floyd, but he’d been my dad’s feline soulmate. George had no hesitation in jumping on my dad’s stomach as he read at night, but his calm temperament was more of a match for my mum. He spent most of his time in my mum’s workroom, at the rear of the house. The sheer amount of creativity that emerged from this room every month was staggering, more redolent of a 1960s Manhattan loft’s worth of bohemians than one retired schoolteacher from Liverpool not much over five feet tall. My mum had postponed her true vocation in life for four decades, but now that she was finally giving it a go, she wasn’t wasting any time. As my mum sewed, cut, printed, etched and painted, George sat nearby. Inevitably, he became her muse. After less than a month, she had already made her own linocut of him. From the shape of this, I sensed his gastronomic life had already improved.

Unlike Floyd, George did not stray far from the house, but when he arrived back, he was usually keen to tell her of his exploits. Sometimes, though, his enthusiasm could get the better of him, with perilous results. ‘I’d just put a load of prints out to dry and I saw him arrive in the room and launch himself towards the table,’ my mum told me. ‘I launched myself towards him at almost exactly the same time and caught him in mid-air, like a rugby ball.’

I could picture this scene vividly, and it made me laugh, but it also made me a bit envious – partly because I wished I had the talent to make lovely linocuts of hares and foxes and cats, but also because I wanted to be able to catch George in mid-air too. I could still clearly remember the ever-softening feel of his fur; what a big, floppy lump of pliable hippie cat he was.

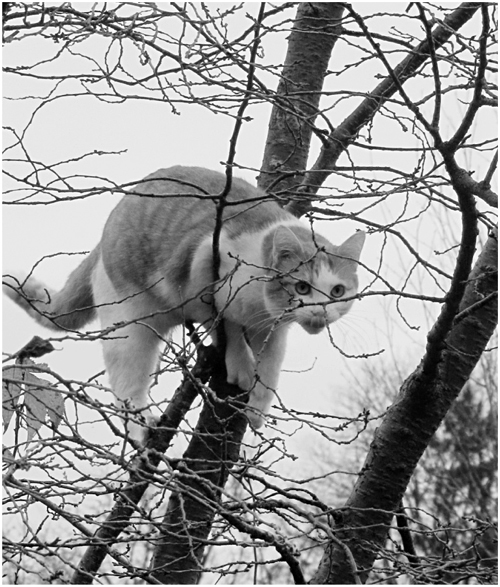

In the famous viral YouTube clip of Christian The Lion, Christian – a lion bought, bewilderingly, from Harrods in 1969 by John Rendall and Anthony Bourke – is seen running joyfully into the arms of his former owners a year after being released into the Kenyan wilderness. This pretty much encapsulates the way I’d pictured my first reunion with George in the days leading up to Christmas 2014. What actually happened is that he strolled lazily into my parents’ kitchen, looked up at me with an insouciant ‘Oh, it’s you’ expression, then said ‘Geeeeooorge’ to my mum, in the hope that she would feed him more of the expensive brand snacks he had become addicted to. George soon warmed to me, and spent a large portion of Christmas Day sitting on my lap looking stoned as my dad told stories about teacher–pupil brawls in Nottingham inner city schools in the 1970s. Later, he stared meditatively at a candle for a full half-hour, mesmerised by the flame. I was coming to the acceptance, however, that this was not my hippie cat that I’d loaned out; this was now my mum and dad’s hippie cat. On Boxing Day, the three of us watched him shin confidently up the cherry tree in their garden, entirely at home outdoors as well as indoors, in his new environment.

‘What a dickhead,’ I said.

‘DON’T TALK ABOUT YOUR MUM LIKE THAT,’ said my dad.

That night, George got a shock; a mysterious white substance he’d never seen before fell from the sky and covered the ground. Tentatively venturing out into it the next morning, he got an even bigger shock as a large lump of it fell from the porch roof, covering him almost completely. Casper, accustomed to snow, made the most of its camouflage possibilities, jumping out at George from behind bushes. The two of them gambolled about in it then fell asleep, paws touching, in front of the fire in my mum and dad’s living room. It was clear that it was George’s house, though, and Casper was, in the end, just a guest. I sensed something a little different about George’s overall manner; something I kidded myself was hurt and a cold mourning for the rural South West, but which was probably just a new nonchalance at his unrivalled place at the centre of a domestic universe. Whatever the case, he had found something here that he had striven so hard for at my house and not quite found: a friend of his own species.

I doubt whether any of my other cats could truly call each other ‘friends’, although they accepted each other more freely than they had in the past. With George gone, The Bear and Roscoe rekindled their alliance somewhat, with Roscoe occasionally to be found asleep spreadeagled across The Bear’s back. One day, a cat food company sent me a taster package, and the courier from the firm they’d employed to deliver it arrived at the front door looking flustered. Apparently, the company had decided to address the package to two of my cats, rather than to me. ‘I’ve been driving around for an hour looking for a pub called The Bear and Roscoe,’ the courier told me. It would probably have been a good pub, and Roscoe had a fair amount of experience in that area, but the name put me more in mind of an American cop show about two reluctant buddies: the old renegade, who keeps promising to retire, and the fastidious youngster, obsessed with paperwork and doing everything by the book. Such a partnership could never happen in real life, though. Roscoe was far too busy. She now prowled the countryside around the house, unchallenged: an outdoorsy country cat who, like me, probably could barely even remember that brief period of being a big city cat. We saw her at night, as she tunnelled stubbornly into us for warmth, and she would often deign to greet us with a high five or two on the garden path when we arrived home, but other than that she was mostly away on business.

I took The Bear to the vet again early in the new year and learned that his lump, his weight and his thyroid condition had not deteriorated. His unretracted claws made him sound like a miniature tap dancer as he skittered across our small living room’s ancient wood floor but, with a new boldness, he skipped nimbly up onto our coffee table when we weren’t looking and attempted to steal chips and broccoli. Shipley frequently followed, and let out a ‘Mrrreewwwwegh’ noise, which I assumed was cat for ‘I really hate you since you’ve been a vegetarian’. Was it possible that both of them actually looked healthier than they’d done in the autumn? As February – winter’s inevitable, much prayed against encore – arrived, I found myself willing The Bear through it towards the day when he felt the first spring sun on his fur.

There were a couple of brief flurries of snow in our part of Devon, but none of it settled. It was different up on the highest part of Dartmoor, where I walked with my friend Mike towards winter’s end. Four miles into our ramble, a bank of snow fog descended, visibility became little more than twenty yards and sleet pounded our anorak hoods at such a furious volume it was hard to hear our own voices. For Mike, an experienced mountaineer who’d spent years as an integral part of the Dartmoor rescue team, this was nothing, and he casually stopped every few yards to tell stories, as if we were walking through a water meadow beside a river on a balmy, butterfly-speckled day in July.

Our conversation somehow got on to the feral cat he’d adopted several years ago at his isolated cottage here on the moor. ‘We essentially got him from Death Row,’ he said. ‘He was called Wallace, short for William Wallace, as in Braveheart. He was the one cat at the rescue centre that nobody wanted, and he’d been cordoned off in his own room. They didn’t even do their usual home visit to check we were suitable owners. They just told us to take him.’ When Mike had bought his house, he’d opened the door to the shed where the electricity generator was kept to what he called ‘a fountain of rats’. He would have liked a friendly cat, but what he was fundamentally looking for was a pest-control pet. He made a bed for Wallace in one of his other outbuildings and, while Wallace virtually scratched the door down during his one foray into the house and never let anyone stroke him or pick him up, he caught hundreds of rats over the next decade until, last year, he died crossing the road near the house.

This was perhaps not a typical stray cat adoption story, but it reminded me of how lucky we’d been with George. All the homeless cats I’d known in the past had a noticeable anxiety or mental scar, however obscure, but George was different: he greeted life with balance and easy poise, as if he’d come from somewhere kind and good – but not too kind and good. Now my mum and dad were desperate to know his story, just as I had been.

‘He’s a mystery man,’ said my mum. ‘He’s all ease and happiness on the surface, but I think he has a lot of secrets, deep down, which he will never tell anyone.’

‘HE WON’T STOP EATING AT THE MOMENT,’ added my dad. ‘HE’S JUST LIKE ALL THE DOPE-SMOKING HIPPIES I USED TO KNOW IN THE SEVENTIES: ALWAYS GOBBLING BISCUITS.’

* * *

It’s spring now, and I’m just back from my second visit to see my mum and dad and George in Nottinghamshire. I noticed another change in George while I was there. It wasn’t just that he looked healthy and well cared for; he has now begun to look almost … posh. He’s become the kind of cat you feel a nagging need to put next to some fresh flowers and render in ink, even if you haven’t got an artistic bone in your body. My mum insists he still takes care of all his own personal hygiene, but he appears impossibly clean and fragrant, almost as if freshly tumble-dried. The initial scratched-up incarnation of him I’d known is now almost unimaginable. He and Casper wrestled, in a friendly way, not long after I arrived but George seemed to have the upper hand. Later, they walked from the kitchen to the living room in perfect synchronicity, tails locked together: cats who, while not identical, find themselves on a similarly mellow spiritual plane. The weather changed for the better a couple of days after that. Overexcited, George leapt through the bathroom skylight and slid down the roof, claws screeching on the tiles, looking imploringly back at my mum. He managed to hold on and climb back in, and half an hour later he was in the garden, watching from a tree in the sunshine as my dad spread his feted ‘black gold’ compost on the flower beds.

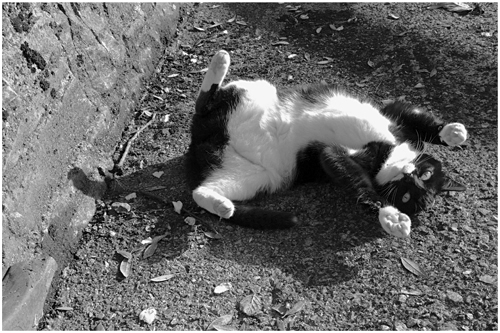

I’ve been sitting outside in the good weather today with my somewhat more motley cats. It’s that special kind of spring warmth that makes felines strut around even more like they own the world than normal. Today, you just know that cats everywhere are acting like they rule the world. Or perhaps that should be ‘acting even more like they rule the world than normal.’ I’m excited at the prospect of a summer in this magical, green place without being stifled by illness. I noted earlier, driving into town, that the ‘Twinned with Area 51’ sign has now been changed back to ‘Twinned with Narnia’. There’s a general feeling of change about, as if winter’s old, doomy air has been sucked away and and a new, positive, spring variety has been piped in.

Shipley has just been on my lap, upside down, contracting his paws on an invisible surface above him, playing a cat version of air guitar. I didn’t actually notice him appear. That’s one of Shipley’s special talents: he’s the loudest, most boisterous cat I know, but is capable, when it suits him, of feats of extreme stealth. Ralph is rolling on a paving slab in a spot of sunlight, ecstatic to be Ralph, as ever, not looking a day over nine. Roscoe has just skipped by, feinting towards me then away, like a nimble winger in a cat football team, and is now peering into the hedgerow, her head down over some work. The Bear is here too, sunning himself near my feet: alert, eager-eyed, polite, a little plumper than he was in November. The Bear is always here, not often the biggest part of the action but close to it, ever observing. How many lives is it he’s been through, now? I’ve lost count. My willing him through to this blossoming, perfect April day was needless. If you overlook the day about a month ago when he fell in the pond, he made it with ease. He is, after all, The Bear.

There has been no talk between Gemma and me of finding a replacement for George. These four cats are easily enough for us. As to dogs, I’m very happy to continue borrowing, rather than owning, one of those. Dogs are mostly great, but I’m not sure I respect their critical judgement quite as well as I do that of cats. If a cat recommended a record to me, I’d listen diligently. If a dog did the same, I’d probably respond in some polite but noncommittal manner then ignore its suggestion entirely. Billy and I have continued on our weekly walks, in which I lecture him on new facts I’ve learned about Devon history while he feigns interest and twangs about the countryside like some elastic posing as a black ball of wool. In February, on one of this winter’s angriest, stormiest nights, Susie had a scare when he vanished from the house of another local friend who was looking after him. When I found her phone message at 5 a.m. I got dressed instantly and was ready to join the search party. He was found not long afterwards, but prior to that I had a sudden, potent awareness of his vulnerability, out there in the gale-force winds with little road sense; a vulnerability far more scary than Roscoe’s, during her disappearance last year. This is perhaps another reason why cats remain my sole official pets – overlooking the STD-carrying ladybirds and the moths, both of which are back with a vengeance.

There have been rabbits, too, but not as many as there were this time last year, and I’m trying to blot most recent episodes involving them out of my mind. I managed to save one Ralph brought in earlier, but then I felt bad and apologised to him: yesterday, Easter Sunday, we ran out of cat food and the supermarkets were closed, meaning all he had to eat last night were biscuits, so it’s only logical he should get a meal of his own, and his choice was neatly appropriate to the season. I do wish, though, that someone would come up with a microchip cat flap that would only let your cat in if he and the animal he was carrying in his mouth were both chipped. It’s right up there near the top of the list of feline-related inventions I’d most like to see, along with food sachets that don’t squirt jellified meat up your arm every time you open them.

Ralph seems to have accepted my apology now. He’s just waltzed over and licked Shipley’s ear, then bitten it, then enthusiastically nutted my hand and meowed his own name. What he’d like to do right now, I am aware, is get on my chest, kick my laptop to the floor, pad and dribble on me then sneeze in my face. Out of all these cats, he’s the one whose affection seems to be the least related to where his next meal is coming from. His motivation is the desire for companionship, and to invite a human to join him in glorying in his magnificence. This is perhaps nothing new; it’s an arrangement that’s been going on between cats and the more manipulable side of humankind for several thousand years. With George gone, he has been returned to his place as Hippie King, high above – at least in his mind – the other members of his court: the fool, the poet and, over there in that bush, the elusive, diminutive but intimidating lawyer figure, who often pulls the strings.

I imagine this scene going on right now is similar to one of those George watched from some dark corner on the margins of the garden exactly a year ago. I will almost certainly never know where his life started, and it boggles my mind and troubles me to try to imagine what situation could have created a cat so lovely, yet so lonely, so I tend not to think about that part. I’ve frequently pictured the bit after, though – the new story that starts from the day I moved to Devon – and I see it a bit like this: He has wandered very far, and encountered lots of people and other cats along the way. There have been moments of hope, but there have been obstacles too – locked doors, dogs, roads – and he’s been on the move for a long time, long enough to feel his own body grow, even in its malnourished state. As he crosses the road in front of the stone cottage under the big moon, he sees the tired man and woman get out of the car carrying what seems to be cats, in boxes. Something about this – and something a little bit soft and gullible in the man’s manner that he recognises in his own – triggers his interest. Is this, finally, what he’s been looking for? He waits around for almost a week and doesn’t see any cats. He survives on rabbits and a few old scraps of leftover chips and burger he finds on tables outside the pub, at the time when the sandy-coloured cat who lives there isn’t around.

Then one day he spots them: four of them, in total. A loud, sweary one, a big, unusually hairy one who looks inordinately happy with himself, a gentle intellectual one and a black and white, industrious-looking one who makes his hormones tingle and buzz. He decides the gentle intellectual one is his best chance of an ‘in’, but when he tries to befriend him, something entirely unexpected happens: the gentle intellectual one is skilled in cat martial arts, and lashes out with a series of complicated flying kicks. It’s not a good start, and things get worse when, on a cold night, a big splash of water hits his head from above. He is tempted to give up, but he doesn’t. There is something here, he is sure; he has sensed it. And one day, just as he is starting to feel as if maybe he is not welcome, a dish full of food appears outside the house. There is nobody else around, but he senses a human presence, watching him. Could the food be for him? Or is it a trap? He is hungry, but he’s feeling wounded from having his initial bold overtures rebuffed. His instinct brought him here, though, and his instincts have been solid in the past; they are, after all, what’s kept him alive until now, against some pretty tall odds.

He decides to be brave, and finds a little trust within himself and moves towards the food. Because, if you don’t live with at least a little trust, what do you have left, except darkness?