It was early autumn in 2013, and I was sitting on the floor in my living room in Norfolk, talking on the telephone to my mum, who was at her house in Nottinghamshire. Around me, as far as I could see, were cardboard boxes. On top of one of the boxes nearest to me was my very large, very hairy cat, Ralph.

‘I think you might regret this,’ said my mum.

‘It will be OK,’ I said. ‘There’s not that much stuff, and it will save me a load of money.’

‘You’re surely not thinking of doing it completely on your own?’

‘No. Seventies Pat is going to drive over and help, at least for most of the journeys. He used to work for removal firms. He’s pretty strong.’

‘Raaaalppppph!’

‘And the two of you are doing this in a van? What kind of van? I think you’re severely underestimating. Two people is nothing, even if Seventies Pat’s a big bloke. You’ve probably got a lot more stuff to take than you think, and it’s going to be very stressful.’

‘Raaaalpppph!’

‘Say that again?’

‘I didn’t say anything. That was just Ralph, Ralphing.’

‘Oh, right.’

‘Raaaalpppph! RaaraaaraaalllPH!’

‘So how is Ralph at the moment?’

‘He’s OK. A bit anxious. He came in with a slug on his back earlier.’

‘Again? How many’s that this month?’

‘Twelve, I think. That I know of, anyway. There could have been others.’

‘Raaaaaallllllllllllllllph!’

It was a frequent habit of Ralph’s to join in with telephone calls from my landline – particularly those which, like this one, involved a somewhat fraught topic. His input largely consisted of either meowing his own name or sitting on the receiver at a point when he felt the conversation had run its natural course. He had always been a loud, opinionated cat, but he had been particularly vocal and agitated over the last few weeks, as the boxes had begun to pile up around him and a couple of his favourite scratching posts – items that, in their younger, more healthy days, I’d still had the audacity to call ‘chairs’ – had vanished to the charity shop.

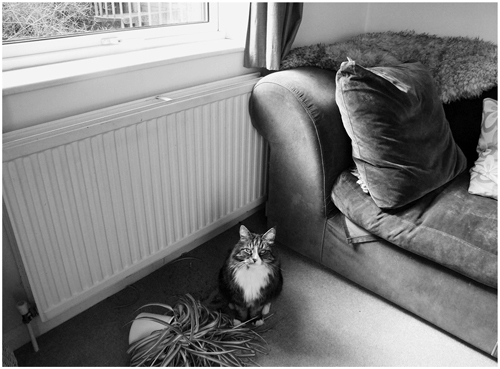

Ralph had a kind of mutton-chopped, early 1970s rock star look about him that, despite his advancing age and popularity with molluscs, retained a certain twinkle. If he’d been a person, he would have been the kind you often found wearing a velvet jacket and a cravat. People frequently thought he was a Norwegian forest cat, or some other fancy longhair breed from the baffling, pampered world of pedigrees, but these assumptions were incorrect: Ralph’s mum had been a common or garden tabby from Romford and his dad an all-black bruiser who would, in the words of his owners, ‘bang anything on four legs’. I suppose at a push you might have called Ralph a Thetford Forest cat, but that was about it. Whatever the case, he was the most visually appealing of my cats, and seemed very aware of this fact. In keeping with his rock star image, he was known to have the odd celebrity tantrum, swanning around the house, climbing furniture and kicking vases and houseplants to the floor, all the while maintaining a steady stream of self-aggrandising dialogue. Recently, the frequency and pitch of these tantrums had increased to the point that, only yesterday, while meow-shouting ‘RAaaaallllph’, he’d taken a running jump onto my sideboard, slid along the surface using the sleeve of a rare 1970s folk record as a skateboard, then, depositing the sleeve and those of two other similarly cherished records on the floor, run across the room and pulled a spider plant off a windowsill.

Ralph’s unease was understandable. In just over a week, if all went to plan, he would be moving from a house that, for almost a decade, had functioned as his own little version of Cat Paradise; a Cat Paradise in which, to his own mind, he was a kind of sideburned Hippie King. In a sense, this was Ralph’s world, and the rest of us – me, my girlfriend Gemma and our three other cats, The Bear, Roscoe and Ralph’s sinewy, foul-mouthed brother Shipley – just lived in it. He swaggered around these large, airy rooms, soaking up their ample sunlight, his only real niggles in life a metal clothes horse he was unaccountably terrified of and an occasional need to bat Shipley into line with a big white fluffy paw. Outside, he had a habitat – green, fertile, leafy, abutted by a lake – which he had come to rely upon equally as his playground, his nightclub and his open-all-hours rodent buffet.

Sure, there had been foes and nemeses for Ralph, but all of these had drifted away. Pablo, defeated ginger opponent in The Great Four Year Cat Flap War of the previous decade, had long since gone to live with my ex. A succession of feral interlopers had been vanquished. After a few tussles, even Alan, the ex-stray who now lodged with my next-door neighbours Deborah and David, seemed to have finally ceded to Ralph’s dominance. Mike, our latest feral – a cat Gemma and I had initially referred to simply as ‘The Wino’ – had clearly long ago been defeated by life, and posed no real threat. Nope: this was Ralph’s place, and he’d never felt more at home here. So why on earth would I want to take him away from it?

This was a question I’d asked myself several times over the last few weeks. The big overriding answer was money. In short, I’d run out of it. I had limped on for a few years, trying to convince myself otherwise, but I could no longer afford to stay in a high-maintenance house with a mortgage this big. Gemma, who was from Devon, increasingly missed home and, not having found work in Norfolk, had taken a temporary job back in the West Country, which meant that she was away for more than half of each month. After a decade here, I also fancied a change: a new environment, possibly even a completely different environment, far away. But the further I’d got into a three-month DIY marathon in an attempt to present it in its most favourable state, the more I fell in love with my weird, topsy-turvy, mid-twentieth-century house all over again.

Sure, the building whose previous owners had named it the Upside Down House had been an absolute bastard to heat, and bore more than a passing resemblance to a 1960s doctor’s surgery, but it had been a happy house, so often full of light and people. And, yes, OK, there had been that time last year when my neighbour David had woken up to find a tent pitched at the bottom of his garden and discovered a paralytic stranger in it with a gun aimed at the adjacent lake, but we were living in a dangerous modern world and you had to be realistic. You might find a good home, but really, were you ever going to be too far away from a drunken man in a tent in a nearby garden, having a nervous breakdown and trying to shoot ducks with an air rifle? In the economic climate of 2013 I was lucky to own a house at all, not to mention a very nice one in a lovely county such as Norfolk. Now, as Ralph climbed up the fitted bookshelves near the telephone, hung off them and meowed ‘Raaalph!’, I felt a fair bit of empathy for him: part of me wanted to cling to the same shelves with my claws and meow ‘Raaalph!’, too.

My mum always watched me with great concern when it came to matters surrounding house moves. When I was growing up, she and my dad moved a lot, taking a few regrettable turns in the process, and she’d always been keen to pass on her wisdom and make sure I didn’t make the same mistakes, or new ones of my own. Such as, say, trying to move the contents of a large three-bedroom home and overstuffed loft alone, in order to save myself a few hundred quid, because my bank account was in the red.

With this in mind, I changed the subject. ‘Where’s Dad? In the garden?’

‘I’M HERE,’ said my dad, who had a habit of listening in on the other line during telephone conversations, and, much like Ralph, adding his own high-volume non sequiturs to the mix.

‘Ooh,’ said my mum, startled. ‘Where did you come from?’

‘ME MUM’S WOMB. IN NOTTINGHAM. IN 1949,’ said my dad.

‘What have you been up to today?’ I asked him.

‘ME AND FLOYD HAVE BEEN HUNTING TOGETHER. WE WENT OUT IN THE FIELD AT THE BACK. HE’S STILL OUT THERE NOW. I THINK HE’S GOT THE SCENT OF A VOLE. YOU CAN SEE IT IN HIS EYES: HE’S GOT THE RED MIST.’

Floyd was my mum and dad’s cat: a one year-old, Rorschach-faced, black and white whirlwind who had recently made a smooth transition from impossibly cute, wool-chasing kittenhood to serial-killing adolescence. After a few catless years, my dad, who had never previously been the most devout cat person, had found an unlikely companion in Floyd. The two of them – sometimes joined by Floyd’s pal from next door, a ghostly white cat named Casper – did pretty much everything together. When my dad climbed a ladder to clean the windows or prune a clematis, Floyd climbed it with him. When my dad took his midday nap on the bed, or in the shady part of the garden he called Compost Corner, Floyd could invariably be found asleep alongside him.

If my dad arrived in his workroom to find Floyd resting at his desk on his chair, he declined to disturb him and instead kneeled beside him, or pulled up an uncomfortable wooden stool from the opposite side of the room. When I’d last been up to Nottinghamshire to visit them, and my dad had emerged from the car wielding several shopping bags, it came as a slight surprise that Floyd wasn’t following behind him, carrying a bag of flavoured deli counter sausages between his teeth. ‘Hunting together’, which took place in the field to the rear of their house, was a new activity for Floyd and my dad, who had recently celebrated his sixty-fourth birthday. I wasn’t sure precisely what it involved, but I knew it wasn’t actual hunting on my dad’s part, but that it did fill a certain chasm in his life that had been there for around thirty years, since I’d last played games of Army with him.

‘I’VE LEFT HIM TO CARRY ON ON HIS OWN AS I HAD SOME LOGS THAT NEEDED CHOPPING,’ my dad continued.

‘So why are you here now, interrupting us and not chopping the logs?’ asked my mum, reasonably.

‘TOM,’ continued my dad, ignoring the question. ‘LISTEN. THIS IS IMPORTANT. DID I TELL YOU ABOUT FLOYD AND THE SHEEP NEXT DOOR? I DON’T THINK I DID, DID I? THEY’VE PUT SOME SHEEP IN THE GARDEN TO KEEP THE GRASS SHORT. I WENT OVER THERE YESTERDAY TO GET SOME CORN ON THE COB I GREW IN ROGER AND BEA’S VEG PATCH, AND FLOYD AND CASPER FOLLOWED ME. I DON’T THINK FLOYD OR CASPER HAVE EVER SEEN SHEEP BEFORE, AND YOU COULD SEE THEM BOTH GOING “FOOKIN’ ’ELL”, AS THEY CAME AROUND THE CORNER. ONE OF THE RAMS, A REAL BIG HARD-LOOKING BASTARD, A JACOB’S SHEEP, STARTED COMING TOWARDS THEM, MEANING BUSINESS. FLOYD WOULD HAVE HAD HIM IF I HADN’T TOLD HIM NOT TO. THERE WERE SOME PEOPLE CAMPING OVER THERE YESTERDAY, TOO. I CAUGHT ONE OF THEM IN OUR GREENHOUSE, TOP-DRESSING A MARROW.’

‘Anyway, Mick,’ said my mum. ‘We were talking about next week. Tom’s decided not to hire a removal company and to do it all himself. I think he’s mad.’

‘ALL SOLICITORS ARE BASTARDS. MOST STRESSFUL THING IN THE WORLD, MOVING HOUSE,’ said my dad. ‘EVEN MORE STRESSFUL THAN GETTING DIVORCED OR DYING.’

‘But you’ve never died or got divorced, so how do you know?’ I said.

‘I JUST DO. I’M SIXTY-FOUR AND I’VE BEEN UP SINCE FIVE O’CLOCK.’

‘I’ve actually been up since five today as well,’ I replied, but the last two words were lost, due to Ralph sitting on the receiver.

‘Raallllllpppppppph,’ said Ralph.

‘Can you stop doing that, please?’ I asked Ralph. ‘It’s really rude.’

‘Raaaaallllo!’ said Ralph.

* * *

Part of me knew my dad was right: having very nearly died in hospital as a four-year-old and got divorced three decades later, I couldn’t quite convince myself that either event was as stressful as the ten occasions on which I’d moved house as an adult. I’d naively hoped it would be simpler this time. One of the most stressful factors around selling a house and buying another is timing: the agonising possibility of finding your dream place, only to lose it when your own sale falls through. I was in no financial position to purchase another house, so by default had the luxury of exempting myself from that particular kind of conveyancing angst. Yet the longer the process of this move went on, the less of a luxury it seemed. The more obsessively I surfed property websites for rented accommodation, the more I realised that I wanted to find a rented house just like my own, the more I realised such a house did not currently exist. I even began to backdate my searches on the property websites that kept old listings up, just to convince myself that at some point in the last couple of years, somewhere there had been an affordable, feline-friendly house to rent in rural or semi-rural surroundings that had fitted bookshelves and looked like the annexe of a 1960s doctor’s surgery.

Like a lot of cat owners, I tended to ask two questions of any potential new home. The first was, ‘Will the cats be happy here?’ The second was, ‘Do I like it?’ If the answer was ‘yes’ to both, and Gemma liked the place too, I could begin to ask more practical questions. This instantly ruled out a vast number of houses in my price range. If I was honest, despite my misgivings about selling my house, I had a feeling in my bones that a move was right for me and Gemma; my real worry was about how the cats would deal with it. None more so than The Bear, an elderly owl poet who had, seemingly to his own immense confusion, ended up in a feline body.

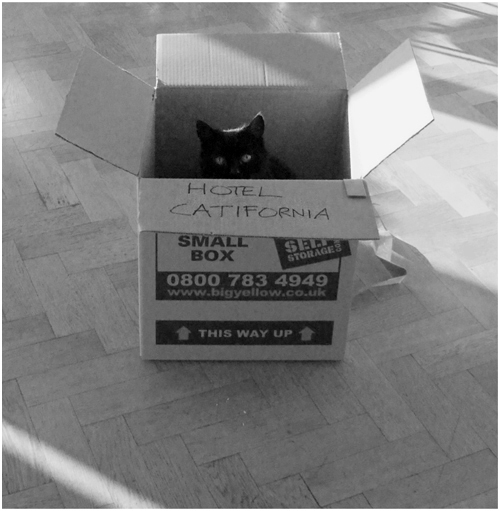

The Bear was eighteen now, could no longer retract his claws, walked with a somewhat camp arthritic wobble and divided much of his time between the house’s balcony and an old cardboard box, on which I’d scribbled the phrase ‘Hotel Catifornia’ in black marker pen. When The Bear emerged from his balcony or from Hotel Catifornia (‘You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave…’) it was invariably to follow me from room to room, staring at me with his big green eyes in a manner which seemed to ask the pivotal question: ‘Can you tell me why I am a cat, please?’ If The Bear was a human, he’d probably have been the kind who listened to records by The Smiths and Leonard Cohen. Opinion was divided on what was truly going on in his mind. Gemma and I believed he was an intellectual empath, who spent his days agonising over the world’s countless problems. My parents, by contrast, thought he was senile. ‘THAT CAT’S LOST IT,’ my dad announced during their last visit. ‘THE LIGHTS ARE ON BUT THERE’S NOBODY HOME.’

The Bear, who’d originally been not only my ex’s cat, but my ex’s ex’s cat, had been a wilful, troubled cat in his youth. Old age, though, appeared to suit him. It seemed, in a Morgan Freeman sort of way, to be the time when he’d discovered the True Him. I actually found it quite hard to picture The Bear in his early and middle years now, so charismatic was his more wizened, philosophical incarnation. The eighteen-year-old Bear was polite, gentle, quizzical and companionable. My conviction that he was a right-thinking feline philosopher somehow seemed reinforced by the fact that he remained the only cat I had ever met who liked broccoli. Not for The Bear the rodent slaughter and territorial squabbles of his contemporaries. He was above that kind of thing, an animal of far greater nuance.

All four cats hassled for food in different ways: Ralph shouted ‘Raaallllph!’, Shipley usually called me a shit satchel in cat language and used my leg as a climbing frame, while perhaps most strangely of all, Roscoe, our lone female cat, preferred to dance across the floor on her hind legs, as if slapping paws with strangers in an imaginary disco bowling alley. The Bear’s approach was more subtle. He’d simply look deep into my eyes, let out a tiny ‘meeeoop’, then nod towards the cupboard where I kept the cat food.

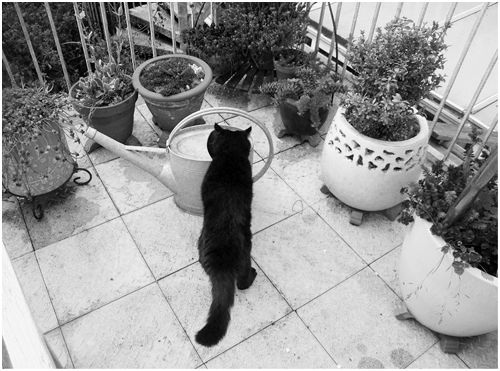

As a rule, the cats were no longer allowed on our bed, due to Gemma’s asthma, but The Bear was so ineffably sweet we couldn’t help making an exception every so often for him. ‘Really? For me?’ his eyes seemed to say, as he settled apprehensively on the duvet in a series of meticulous, circular padding manoeuvres. ‘I’m just so … honoured. I really don’t know what to say.’ The Bear’s spine felt more brittle than it once had and he moved more awkwardly, but his fur shone, and in the last couple of years he’d required the services of our local vet barely half as much as any of the other cats. He had been for a rare visit not all that long ago, after which, due to his unusually large appetite and slight weight loss of late, he’d been tested for an overactive thyroid gland, but the tests had come back negative. A few months on, he was plumper and glossier than ever. I knew The Bear couldn’t live for ever, but another part of me was starting to wonder if the old, stagnant rain he slurped from his favourite watering can on the balcony every day was in fact an elixir of eternal life, its formula mixed clandestinely under a full moon while the rest of the house slept.

I’d long maintained that The Bear’s hypersensitive ears could detect the sound of conveyancing at a hundred paces, but this time he seemed wise to the move from the moment the estate agent stepped through the door, tape measure in hand.

‘I’m afraid we can’t have any pets in the pictures,’ said the agent’s photographer, spotting The Bear on the bed, as he took the photos of my exhaustively spruced and decluttered rooms. This I did not understand at all: I’d always been more attracted to a house when I glimpsed the reflection of an errant cat in a mirror, curled up on a bed or standing defiantly on a kitchen work surface in a photo on the Rightmove or Zoopla websites. ‘But you can’t take photos of the house without The Bear!’ I wanted to protest. ‘The Bear is this house.’ However, because I’m painfully English and polite, I didn’t, and instead meekly and obediently moved The Bear to the balcony, his deep, betrayed eyes burning into me all the while.

‘Sorry,’ the photographer continued. ‘I don’t mind being near them but I can’t touch them.’ I couldn’t quite work out what he meant by ‘them’: cats in general, or specifically elderly academic frustrated diplomat cats whose eyes drilled into your soul.

Far more than Ralph’s increased Ralphing, Shipley’s shouts of ‘Spunk box!’ and ‘Piss officer!’ and a new, vaguely perceptible nervousness in Roscoe’s manner, it was those questioning looks from The Bear that made me feel I was a terrible person for moving house. ‘So you’re really doing this?’ The Bear seemed to be saying to me. ‘After all we’ve been through together to get here?’ The Bear’s longevity might have been put down to many factors – an innate sense of his own limitations that many other cats lacked; his quiet literary lifestyle; a diet containing just the right mix of rainwater, mechanically recovered meat and broccoli – but I knew that a big part of it was almost certainly due to his happiness and stability here, in this house, for the last decade. If I was going to move The Bear again, it would have to be to a place where he, and the other cats, would be at least as comfortable and happy as they’d been here: a place where there were no major worries about roads, with a bit of green outdoor space and enough indoor space to give all four cats as much chance as possible to peacefully coexist. An extra plus for The Bear, whose joints were getting stiffer all the time, would be a staircase that wasn’t formidably steep.

All of this considerably narrowed the available pool of rental properties. Then there was the fact that landlords seemed to have tightened up their rules on pets in the eleven years since I’d last signed a tenancy contract. Many times while house-hunting, I would tell a letting agent ‘I have cats’, yet somehow what it would always feel like I was saying was, ‘I have a large, volatile dragon who likes to party.’ Around half of the population of the UK lives with one or more cats, but, as a prospective renter, being in the majority suddenly reduced me to the status of an untrustworthy leper. ‘But one of them isn’t really like a cat at all,’ I wanted to protest to the agents I spoke to. ‘He’s more like a small version of David Attenborough with fur.’ At least I’d been lucky enough to find some buyers for my house instantly: an impossibly elderly couple who were more or less the exact opposite of the buyers I’d imagined, and who stalked slowly yet purposefully around the place making a gradual, slightly surreal inspection of my possessions – a log cabin quilt made by my mum and a woodcut of a fox, for example – and asking if they would be included in the sale. After a few days they decided to withdraw their offer, having come to their senses and realised that, what with each recently passing their hundred and seventy-fourth birthdays, a three-storey building with East Anglia’s steepest garden might not be a practical option. My replacement buyers – who, again luckily, followed immediately – were far less incongruous: two friendly civil servants wanting to escape the Home Counties commuter sprawl, who would be bringing with them a grumpy old ginger cat called Doris and a passion for mid-twentieth-century interior design. But they needed to move quickly. Which was fine by me, and entirely feasible if you overlooked the fact that Gemma and I were yet to come even close to deciding which part of the country we wanted to move to, let alone which house.

Our initial search had taken place in Gemma’s home county of Devon, a place whose clear rushing rivers, wild moors, craggy prehistoric woodland and jagged, vertiginous coastline had been having an increasingly seductive effect on me for over a decade. House-hunting from 360 miles away was not easy. Out of absolute necessity I’d sold my car a few months before to fund the improvements to my house, so visits to the fairly remote bits of Devon we were searching in required me to use a hire vehicle. Usually, by the time I had picked this up, found a viewing time convenient for everyone concerned and made the cross-country trip, the best houses we were looking at had been snapped up. All of the few places left to view that allowed pets fell short in at least one way: they were too expensive, unsafe for cats, too remote for Gemma, who was a non-driver, or had dingy rooms that smelt like feet. In the midst of all this, I made calls to our solicitor, whose indolence was putting me in severe jeopardy of losing the sale. Climbing tussocky hillocks and walls in a desperate bid to get phone reception, I’d finally get through to him, then invariably be cut off at the conversation’s most vital juncture. Why had he not made a call to the building regulations department like he’d promised to, leaving my buyers convinced they’d lost the house? Why was he sitting on forms I’d filled in weeks ago, as if incubating them like some overweight chicken in a posh shirt? At the end of my tether, I opted to take the bits of conveyancing he couldn’t be bothered to do into my own hands and found them surprisingly simple. But still the big question remained: where would we live?

Much as Gemma and I loved Devon, the idea of moving there terrified us. Actually, that’s not true. The idea of moving there made Gemma feel warm inside and me feel inspired, nervous and excited. The idea of moving four cats there terrified us. This would entail a journey in which we kept The Bear, Ralph, Shipley and Roscoe in carriers in a car for around six hours, and that was only if we were lucky and didn’t run into any big traffic jams. Rethinking, we began to widen our criteria to include much of the area between Devon and Norfolk, reasoning towards a more moderate first step west. We also continued to search in Norfolk itself, since neither of us had completely abandoned the idea of continuing to live there. But so much choice, far from being freeing, had a dizzying, tyrannical effect, sending me off on irrational bug-eyed, last-minute drives to unknown territory, and frantic local research missions that left me feeling like a five-year-old who’d been spun around repeatedly by his arms in a big confusing garden. ‘I have seen a nice, almost affordable house near the village of Tubney Wood, one hundred and seventy miles away, and I cannot call the letting agent because it is Sunday and they are closed, and I have no knowledge of Tubney Wood, or what it’s fundamentally about as a place, but I still have a few hours until the hire car is due back at the depot,’ I would reason to myself. ‘I know! I will drive to Tubney Wood, to check out the house from the outside, and confirm whether its garden wall really is too high for cats to climb and reach the adjacent road, as the picture on the letting agent’s website suggests.’

After two heartbreaking near-misses on cat-friendly places – the first a quiet, church-owned town house necessitating the submission of a lengthy ‘tenant’s essay’, whose junior estate agent incorrectly assured us ‘Don’t worry! You’ll get it!’, the second a one-storey, two-bed modernist architectural masterpiece whose rent had been capped at a strangely affordable price due to its lovely bearded architect landlord’s wish for artists to live there, and which I was three agonising hours too late in applying for – I arrived back in Norfolk from yet another cross-country drive, blurry-pupilled, muddle-brained and spent, with nine days to go until the completion date on the sale, and proceeded to fill the tank of my diesel hire car with petrol. As I sat on the grass verge, half a mile farther up the road, and awaited the tow truck, I called to cancel the borderline insane viewing I’d arranged in an uncharted part of Somerset the following day and decided to admit defeat. I’d not only been trying too hard, not wanting to let anyone down – Gemma, The Bear, Ralph, Roscoe or Shipley – but also hoping to find a writing haven I could fall in love with which would comprehensively replace my existing house in my affections. I would opt for a different approach: I would, quite simply, find us somewhere to live.

* * *

Back in early summer, when we hadn’t officially been looking for a house in or near Norwich, the place was full of attractive, light, cat-friendly places to rent on quiet roads. Now, four months later, the one feline-accommodating place that fitted our budget, timescale and most basic requirements was a fairly nondescript bungalow on the edge of the city with a garden made almost solely of concrete. Even securing a viewing for this required a certain amount of subterfuge. Shattered from my many drives west, the diesel incident and sleepless nights worrying about conveyancing, I’d visited the letting agent in person, looking, if not in the midst of homelessness, then as if I was doing a pretty convincing dress rehearsal for it. It hadn’t occurred to me that being tired, sorely in need of a haircut and wearing old clothes would disqualify you for eligibility for a small, one-storey 1970s house near Norwich, but I’d barely stepped in the door and it was clear that the lady at the front desk wasn’t getting a great vibe from my ancient charity shop duffle coat.

‘Nope, sorry,’ she told me snippily when I asked about whether the bungalow’s landlord would take cat-owning tenants. ‘Absolutely no pets on that one.’

‘Oh, that’s a shame,’ I said. ‘Do you have anything else of a similar kind?’

‘No, nothing at the moment,’ she said. ‘Sorry.’

At which point, to make it doubly clear that it was time for me to leave, she swivelled her chair rather theatrically back towards her computer monitor and the more pressing tasks of the day which, from what I could gather from the travel agent’s homepage open in her browser window, involved an imminent holiday to the San Lucianu beach resort in Corsica.

Undeterred, on arriving home I called the lettings agency again, putting on the respectable voice of someone who owned a far nicer coat and explaining that I was a writer who owned cats and would like to view the bungalow. The agent’s voice sounded very similar to that of the one I’d spoken to earlier in the day, but I couldn’t be sure if it was her. Whatever the case, within a few minutes I’d established that the landlord was very happy to accept cat-owning tenants and arranged a viewing for the next day.

‘ALL ESTATE AGENTS ARE BASTARDS,’ said my dad when I told him about this episode. ‘I CAN SEE WHERE THEY WERE COMING FROM WHEN IT CAME TO THAT COAT, THOUGH. NEXT TIME YOU’RE ON A COUNTRY WALK, YOU SHOULD TAKE IT OFF AND LEAVE IT AT THE SIDE OF THE ROAD. THE RSPCA WILL COME AND TAKE IT AWAY. COME TO THINK OF IT, ARE YOU SURE THE LETTINGS AGENCY DIDN’T MISHEAR YOU AND THINK YOU ASKED IF THE LANDLORD ACCEPTED COATS?’

The bungalow was hardly ideal, but idealism was out of the question at this stage. The garden resembled the kind of small down-at-heel car park you might find at the rear of a suburban dry-cleaner; the toilet floor was straight from a neglected 1980s shopping arcade and the council tax was extortionate, presumably due to the fact that from the kitchen window you could just glimpse some of the rooftops of houses owned by rich people. On the other hand, it was warm, clean, within walking distance of several of our friends and three or four of our favourite pubs, positioned at the end of a quiet cul-de-sac and had an area of rough ground to the side of it that promised to be a prime feline roaming area. I began to think of the place primarily as a retirement bungalow for The Bear: a cosy new hideaway for him, complete with single-storey layout and, courtesy of Gemma and me, round-the-clock catering.

It had to be noted, though, that The Bear’s three furry housemates showed little inclination towards retirement. Ralph and Shipley were a little lazier than they’d once been, certainly, but between them still kept up a weekly vole and mouse count of around one per day. These rodents would very rarely get completely devoured, being instead either abandoned completely intact or with just their faces or rear ends remaining. In the former scenario, I’d often arrive in the kitchen to find The Bear – who’d never, to my knowledge, killed anything – standing over the corpse looking despairing and mournful, as if steeling himself for the thankless task of informing its next of kin. Twelve years of living with Ralph and Shipley and dodging vole faces and mouse innards had made me nimble on my feet, and I was hardened to the clean-up process, but rapidly diminishing floor space and clutter in the build-up to the move made matters more treacherous. So far during packing, I’d found a decomposing mouse in an old Scrabble box and a shrew’s face folded into one of the dust sheets I’d been using while decorating. I sensed I’d only scratched the surface here, and that the unpacking process was going to be full of new and terrible discoveries.

Roscoe, too, was busy, but in a less bloodthirsty way. She was a small, cartoonish-looking cat, with shocked button eyes. At the tip of her black tail was a tiny, endearing smudge of white – a distinguishing feature that Shipley had briefly shared on the day I’d painted our stair rail in gloss magnolia. Despite Roscoe’s somewhat vacant looks, she maintained the industrious air of a cat who was constantly running late for an important corporate PowerPoint presentation. Even those somewhat overdramatic arrivals of hers at feeding time, on her hind legs with her paws in the air, gave off the suggestion that she was squeezing us into a tight schedule: that we should be grateful for her presence, and perhaps offer her a high five or two by way of thanks. Of all the cats, Roscoe was the one I was least worried about transferring to a new house. She’d not had as long as the other cats to get truly established in this environment – Gemma and I had adopted her only a year and a half earlier, when she’d been just a few months old – and, despite being physically vulnerable, a permakitten in size, she possessed an independence the three others didn’t. You wouldn’t find her meowing her own name, swearing petulantly in your face for no reason or staring up from the kitchen floor, contemplating the void of existence. She was, all told, a bit aloof, but in the feline dynamic of the house, having one aloof cat was actually OK: it served to counterbalance the other three somewhat needy ones. Before Roscoe’s arrival, Shipley had repeatedly bullied The Bear, shouting monstrous insults in his face and interrupting his meditation sessions by clocking him on the head, but this had calmed down noticeably, largely as a result of Roscoe comprehensively decking Shipley whenever he got out of hand. On these occasions Shipley’s face would express the same shock and fear a football hooligan’s might after being kicked powerfully in the testicles by a small female child.

Roscoe had grown into her name: she was an outdoorsy tomboy who could amply take care of herself. Even a couple of advances from Mike the feral hadn’t fazed her. That said, it was hard to imagine Mike really intimidating anyone. With a downturned mouth, rough, scabby fur and a face shaped, in the words of my friend Will, ‘like he’d swallowed a saucer’, his appearance seemed to sum up all the woes of being homeless in David Cameron’s Britain.

If anything, I was actually looking forward to moving Roscoe away from here. The house was next to a main road, but the tall fence I’d had built almost a decade before and several years of thick ivy growth on that side of the building meant that it was extremely difficult for cats to get to the tarmac. Besides, The Bear, Shipley and Ralph had long since worked out that all the interesting stuff was on the non-road side of the house. However, during the place’s recent makeover, I’d cut down the ivy in order to paint the fence and the bathroom window frame, which meant that it was now possible for a cat as small as Roscoe to squeeze through the bars onto the driveway. The night after I’d finished chopping the ivy back, I’d been up there to put the bin out and found her and Mike sitting a few yards away from each other, in worrying proximity to the road: two cats from different planets, Business Cat and Wino Cat, involved in some kind of arcane stare-off. My attempt the next day to block the gaps off with chicken wire proved unsuccessful. When Roscoe wanted to get somewhere, she made it happen. She was that kind of cat.

With this in mind, the move could not come quickly enough.

Where had Mike come from? I had one theory, which involved the ivy itself. Mike was actually just the latest in a succession of ginger cats to have visited us over the last couple of years, all of whom had been feral, all of whom had proved costly in an emotional and/or financial sense, and all of whom seemed initially to have emerged from the ever-expanding area where the ivy was located. I’d asked all of my close neighbours, and nobody seemed to know the origin of any of these cats. I’d come to see them as being a little like the slayers in the TV show Buffy the Vampire Slayer: there could only be one in the area at any one time but, as soon as one died, a replacement arrived. Sometimes, though, there was an administrative error and you got two at the same time.

The first of the ginger strays had been Graham. Moonfaced and with fur that spoke of a life of hard knocks, Graham had begun making his night-time raids on the house in early 2011, during which he would steal biscuits and then take a large piss either on the blackboard in the kitchen or the W to X section of my LP collection. After many months of trying, Gemma and I managed to ‘befriend’ him (ie, block off the cat flap when he was in the house) and, with the hope of either adopting him ourselves or fobbing him off onto my mum and dad, took him to the vet’s and had him castrated, tested for feline AIDS and inoculated against various cat diseases. Not long after this, he’d escaped, which had left us feeling sad, and also not unlike some kind of charity for feral cat testicles. He did return a couple of times, but only to take a retaliatory piss on my Bill Withers albums, and had not been seen since spring this year.

The permanent departure of Graham had no doubt been hastened by the arrival of Alan, the Eliza Dushku to his Sarah Michelle Gellar: a cockier, more physically intimidating cat, who was better at talking to strangers and with whom Graham would often fight. The story of Alan had a happy ending, since he was now looking sumptuously upholstered and living in luxury next door with Deborah and David and their elderly female cat, Biscuit (a fellow ginger, who’d spent much of the last decade coldly rebuffing a series of polite romantic advances from The Bear). ‘Oh, Alan!’ I’d often hear Deborah shout, which sounded like she was reprimanding an insurance broker who’d let her down in some way, but usually just meant that Alan had done a big piss in one of her shoes.

There was a brief lull in feral activity during this period, before the arrival of another stray whom Gemma and I referred to as ‘Basil Bogbrush’. This sour-faced, wiry-haired creature only hung around for a fortnight or so, and our relationship with him stalled at the first hurdle. That is to say, Gemma and I walked down to the supermarket and bought him some cooked turkey chunks – ‘They’re the same ones my brother has on his sandwiches!’ remarked Gemma, somewhat taken aback at my extravagant choice – then threw some of them gently in his direction, in response to which he growled at me like an irate honey badger and walked off. He was almost instantly replaced by Mike, who, despite having the appearance of a cat you’d find spoiling for a fight after trying to bum a cigarette off you outside your local Costcutter, was actually very sweet. I was keen to find Mike a proper home, and Gemma and I had seemed to be getting somewhere in winning his trust up to the point when, about four weeks ago, he’d vanished.

As with Graham, I blamed myself for Mike’s disappearance. I’d last set eyes on him about a week after I’d cut the ivy in the messy, straggly moments of the final party to be held at the Upside Down House. Seventies Pat, our friends Dan and Amy and I had been taking turns to sing rock anthems in my living room and I’d turned to see Mike at the window, forlornly staring in at us. I was suddenly struck by a wave of middle-class guilt, looking at his pitiful face and standing in my warm house, surrounded by empty beer cans, records and the debris of an abandoned game of Trivial Pursuit. I’d gone out to say hello to him, but Pat, Dan and Amy had called me back in, as it was my turn on the microphone, and ‘Long, Long Way from Home’ by Foreigner was all cued up and ready to go. What followed was an extremely painful, overreaching rendition, even by my normal tone-deaf standards. By the time it was over, and I’d had the chance to root around the food cupboard for some treats for Mike and return outside, he had vanished, and the night hung heavy and silent. He had wanted to know what love was and, selfishly, I’d been too busy singing to show him. Now, a few weeks on, I was starting to face the fact that he might be gone for ever: not the first cat I’d lost, but almost certainly the first one I’d lost via karaoke.

It had taken two full days of sawing, chopping and pulling to get rid of all the ivy. I listened to New Yorker magazine podcasts and shuffled songs on my iPod to keep the tedium at bay. During day two, the shuffle function arrived at ‘Ivy, Ivy’, a haunting song by the 1960s baroque pop group The Left Banke. I’d never known why it was called ‘Ivy, Ivy’ before, but now I worked it out – it was because all ivy is a massive shithead, and all ivy has even more ivy underneath it, which is even more of a massive shithead. ‘Forget guns and bombs,’ I thought, as I hacked at the knotted, throttling limbs and choked on their dust fumes. ‘If I ever need to protect myself from an advancing army, I’ll just cover myself completely in ivy.’ As I began to get down to the last layer, my forearms scratched to ribbons, there was a temptation to hack more and more exuberantly, but I restrained myself, careful to look where I was cutting, still convinced of the ginger cat nest I was poised to uncover. In the end, though, all I found was an old golf trolley and a few old beer bottles, no doubt thrown over the fence by local revellers back in the rowdy summer of 2006.

The Bear, standing above me on the balcony, came over and watched with particular interest during the closing stages of the job. There was that look in his eyes again, the one that said: I know all your secrets. Except now it was more intense than ever. For him, Ralph, Shipley and Roscoe, what my house improvements essentially amounted to was a gradual destruction of all their favourite hang-out spots. As well as the ivy, there was the tilted, rotting shed, upon which each of them had liked to urinate, now smashed down and burned by me, with the help of David and David’s biggest mallet. Then there was the hole in the boiler room wall – always such a point of fascination for Ralph, and now sadly filled in. Even Hotel Catifornia had become the victim of heartless redevelopers during the packing process. Near unrecognisable from its former cosy, welcoming state, it now contained some pottery, three old table tennis bats and a file of tax receipts from 2007.

I left the two most arduous jobs until the last minute: clearing out the loft and the American-style crawl space beneath the house, both of which, in archetypal loft and crawl space fashion, were comprised of one per cent genuine valuables and 99 per cent junk I’d told myself I should hold onto just in case I ever needed them, even though it was patently obvious I never again would. In what ‘just in case’ scenario, for example, had I thought I’d need half an old broken vacuum cleaner? Just in case I suddenly discovered I’d become an entirely different person and made robots out of broken vacuum cleaner halves? How did a human – a not especially materialistic human, without children, at that – accumulate so much stuff in less than four decades? My adult life seemed to be separated into two distinct chunks: the first relatively brief one, where I was keen to gather possessions, in the view that they made me more of a person, and the subsequent lengthier one in which, having realised they didn’t, I’d been doing my best to jettison them. Recently I’d being travelling to my local charity shop and household waste recycling centre so often, I’d started to go to other, more distant charity shops and household waste recycling centres just to shake things up a bit. When the crawl space was finally clear, and I’d banged my head on its hard, knobbly roof for the last time, I breathed such a huge sigh of relief that I let my guard down, enabling Ralph to scuttle past me and achieve a decade-long ambition by descending into its furthest recesses. As he ventured into a part of the crawl space far too narrow for me to have ever explored, the echoing ‘RAAAAAAaaaallllph!’ he let out somehow sounded like a Charlton-Heston-in-Planet-of-the-Apes cry of pain: a lament for the cruelty of humans, or at least for this new hidey-hole which was to be snatched away from him less than forty-eight hours after he’d discovered it.

Half an hour later, after I’d coaxed Ralph out of the crawl space, I took my final stroll around the garden with him and the other cats. Shipley, Ralph and Roscoe always seemed to burst into life whenever Gemma or I came outside. Shipley, especially, had a sixth sense about it, somehow knowing, from a sleeping position somewhere deep in the house’s bowels, that I was in the garden, and instantly appeared alongside me to box the back of my legs and call me names. In what now constituted a rare privilege, we were joined by The Bear, who typically tended to keep his outdoor activities combined to the balcony and a window ledge next door which provided a direct view of Biscuit’s favourite sleeping spot. Ralph rolled about in a patch of sunlight, Shipley hurtled down the sloping lawn, his momentum taking him all the way to the top of the apple tree at the end, and Roscoe danced about in his wake, before becoming distracted and heading off to the hedgerow to inspect some blackberries, perhaps having mistaken them for the electronic kind on which you could check your email.

The Bear scuttled down last, keeping his distance from the other cats, but showing impressive speed for a pensioner. He refrained from following Shipley up the tree, preferring instead to unleash a jet of hot yellow urine against its trunk. Beneath this tree was buried Janet, a large fluffy black male cat who, prior to his demise from a heart attack a few years ago, had been another intellectually inferior tormentor of The Bear and one of Shipley’s most persuasive early influences. As The Bear dampened the bark, he stared straight at me and widened his eyes just a fraction. Was this a final, typically wry and Bearlike gesture of revenge on his old adversary? Perhaps.

Surveying the garden and those surrounding it for the final time, it struck me that this small Norfolk hillside was a patchwork of cat history. There was Janet’s tree, which Janet and Shipley had so loved to climb together. Moving all the way down to the bottom of the hill, there was the rotting jetty at the edge of the lake, from which The Bear and I had once rescued a turtle who’d got itself trapped in the structure’s wire meshing. Below this was the murky water from which, for some bizarre reason known only to himself, Janet had obsessively fished old sweet wrappers and crisp packets. Moving back up the hill we reached the pampas grass where, not all that long ago, Ralph, in one of his more optimistic moments, had attempted to hunt a muntjac deer. Beyond that, off to the right, was the run that held Deborah and David’s six chickens, all so mysteriously feared by the normally swaggering Shipley that, whenever he ran past them, he made a frantic wibbling noise, which seemed to translate as ‘Shit shit shit shit shit shit’. Turning sharp left, you reached the former site of the feral ivy nest; the mouldy deckchair cushion that I’d left out for Graham, then Mike, and still couldn’t quite bring myself to throw away; the cypress bush under which Ralph had once sat beside a hedgehog for a whole afternoon; the gap in the hedge where Alan made his escapes, in his and Ralph’s epic duels; the window The Bear smeared with his cat snot while gazing in at Biscuit. There was no denying it: this was a place with a strong cat theme. It probably shouldn’t have mattered to me that it remained a place with a strong cat theme, since, after I’d moved the last of my possessions in three days’ time, I would almost certainly not be coming back here ever again, but it did. When my initial buyers had announced that they weren’t fond of pets, I’d felt a small cold space open up in my chest. This house had caused me a lot of stress, but that didn’t mean I didn’t want it to be happy when I was gone, and the idea of it being happy seemed synonymous with the idea of it being filled with four-legged life. I couldn’t imagine Alan and Biscuit without nemesis cats – or, at the very least, other, lesser furry creatures – next door, to help define them; couldn’t imagine the kind and thoughtful Deborah and David living next door to non-animal lovers. And what about poor Mike, in the unlikely event that he did decide to come back?

I had been enormously relieved to find out that my replacement buyers were cat lovers. Naturally, I briefed them about Mike. Even if I hadn’t wanted to do it for Mike’s benefit, it seemed like one of those things you do out of courtesy when you sell a house: you inform the people moving in about the best takeaways nearby, the nicest country walks, the nearest doctor, the code to the burglar alarm and the local nest of feral ginger cats.

It pained me to think about Mike, or even Graham, still being out there somewhere after I’d gone, but I couldn’t afford to dwell on that: I’d drawn the line now. Besides, I’d arguably already let the needs of cats detain me at this house a year or so longer than I should have.

With the note to the new owners written, and all but the last few things boxed up, I made my way through the cardboard jungle to bed in the house for the second to last time. The Bear padded along campily behind me. I was due to be up in five hours, but I didn’t set an alarm. There were enough noisy cats here. I knew I could rely on them. Sooner or later, one would meow his own name, or call me a dreadful swear word, and I’d know it was time to make a start on moving my life to a new place.

* * *

Between solicitor stress, packing, shedding possessions and my obsessive, manic house-hunting expeditions over the last few weeks, I’d still not managed to find the one good solid night’s sleep that might lift me out of the same state of absent-mindedness that had caused me to pour destructive alien liquid into an automobile I didn’t own. So it was perhaps no surprise that the first thing I did, after getting into my hired van in the depot the following morning, was drive it straight into the car it was parked beside. I blame extreme tiredness for this, but in a bigger way, I blame the van hire company themselves, who, after talking me into upgrading to the biggest van I was eligible to drive (a van I made clear to them was much bigger than any I’d ever driven in the past), handed the keys to me without offering to get the van out of the extremely tight spot it had been parked in. I spent the whole journey back to my house cursing my exhaustion for making me less assertive and failing to ask for the van to be moved. The scrape on its wing was barely noticeable, but I’d really crunched the Vauxhall Zafira that had been parked next to it. I didn’t know what the damage would amount to, financially speaking, but I suspected – rightly, as it later transpired – that, in one moment of idiocy, every penny I’d saved by not using a removal firm had been frittered away. I wondered if the best thing to do before I next saw my mum in a couple of days would be to write down her ‘what did I tell you?’ lecture and hand it to her, just to save her the hassle of delivering it to me.

After another sixty-mile round trip, during which I loaded and unloaded a van full of stuff on my own, I was, to say the least, grateful for the arrival early that afternoon of Seventies Pat.

‘All right, dude?’ Pat said, handing me a six-pack of lager as I opened the front door to him. Six foot two and a half in his snakeskin cowboy boots, he represented a reassuring if somewhat unlikely moving-day spectacle, his long blond hair, cravat and corduroy bell-bottoms rippling slightly in the autumn breeze. A few of my friends favoured clothes from the middle of the last century, but Pat was the only one you never found off duty. I’d not had the privilege of seeing his nightwear, but I suspected that even his pyjamas were made from crushed velvet and had a slight flare to them. His reputation for rock dandyism preceded him in his native Black Country, to the extent that recently, during a routine transaction involving a pasty in the Dudley branch of Gregg’s the bakers, the cashier, who he’d never met before, had paused and looked him over for a couple of seconds, then asked, ‘Are yow Seventies Pat?’ – to which Pat had replied, ‘Yep.’

The plan was that Pat and I would shift the rest of my stuff unaccompanied, over the next two days, before Gemma, who was back in the West Country for work, arrived to assist with the unpacking. Pat was helping me out of the kindness of his big corduroy heart, his only payment being a brace of Indian takeaways and a couple of original LPs by the 1970s Irish folk group Planxty I’d picked up for him the previous week in Norwich, but he did have an ulterior motive. Pat had never been a cat owner himself, but possessed a serious soft spot for Ralph, in whom he recognised a kindred spirit. I knew Pat would never attempt to steal Ralph, but it was an unspoken fact between me, him and Gemma that, should Gemma and I perish unexpectedly, Ralph would go to live with Pat in Dudley. Once there, the two of them would live the life the Lord intended them to: waxing their sideburns together in front of his ’n’ his mirrors while listening to a T. Rex album before heading out to hog the jukeboxes and pool tables of the Black Country’s finest real ale pubs, as an assortment of leather-clad rock chicks looked on admiringly. We wouldn’t be taking the cats until our final journey to the bungalow in a couple of days, but it was established very quickly that, when the four of them were divided up for the journey, Ralph would be travelling in Pat’s car, not in the van with me.

‘I’ll let you take The Bear,’ said Pat. ‘I love that little dude, but he freaks me out, the way he stares at me. I feel like he’s planning something.’

Pat’s fear turned out to be a self-fulfilling prophecy when, the following morning, I arrived in the living room to find Pat standing beside the sofa bed on which he’d slept the previous night, inspecting a large vomit stain.

‘All roight, now listen,’ said Pat. ‘I just want to make one thing clear straight away: it wasn’t me who did that.’

Behind us on the windowsill sat The Bear, looking the opposite way and cleaning a paw. There was something a little bit forced about the way he did it, suggesting that, were we to check, we’d find that his paw hadn’t actually needed cleaning at all.

‘It’s OK,’ I said. ‘It’s probably just one last protest before we leave.’

‘I can’t believe he had time to do it,’ said Pat. ‘I only went into the bathroom long enough to have a slash and spray myself with Old Spice.’

‘Yeah, he can still move quickly when he needs to.’

On the whole, I had been very impressed at the way The Bear had dealt with the few days immediately prior to the move. There had been none of the last-minute disappearing acts or desolate meeooping sessions that had characterised previous relocations. Instead, he seemed watchful and curious, always keen to keep an eye on the action but never seeming quite to disapprove of it. I even caught him climbing the ladder after me and trying to get into the loft at one point, which made me wonder if those house-hunting worries about staircases were a little premature. When I finally fed him into his cat carrier, he felt soft and compliant, rather than rigid and stubborn, as he always had at these moments in the past. I took his sanguine attitude as further confirmation that I was doing the right thing.

Of course, it could be argued that each of us still had unfinished business here. I’d never got around to building that writing shed I’d often talked about, or getting the goat I’d always wanted for the garden and, despite many efforts, The Bear had never melted Biscuit’s icy heart, but we were both men of the world now, old enough to realise that life was never going to be a perfect To Do list on which you managed to tick all the boxes.

‘Don’t worry – we’ll be there in no time,’ I said as I started the van for the final journey to the bungalow, with The Bear and Roscoe belted in in their carriers on the two passenger seats behind me, but my reassurance was superfluous; the two of them were amazingly placid. Following behind us in Pat’s car were its owner and Ralph: Seventies Pat and his Seventies Cat. Behind them were my mum and dad, who’d driven down at the last minute from Nottinghamshire to give me some much-needed assistance cleaning the house, with the very last of the boxes, one of which contained Shipley.

‘THIS CAT IS A GOBSHITE,’ said my dad, emerging from the car with Shipley, on reaching the bungalow. ‘HE WOULDN’T SHUT UP ALL THE WAY HERE. I’M SURE HE CALLED ME A WAZZOCK AT ONE POINT. IS HE ALWAYS LIKE THAT?’

‘Pretty much,’ I said. ‘Haven’t you noticed before? Then again, I suppose you’ve only known him for twelve years.’

‘DON’T BE FOOKIN’ CHEEKY, YOU LANKY STREAK OF PISS. I DON’T ALWAYS REMEMBER THINGS. SEE IF YOU REMEMBER THINGS WHEN YOU’RE SIXTY-FOUR AND YOU’VE BEEN UP SINCE FIVE.’

For the time being, I installed the cats in the spare bedroom with some food and water. The water was split between a dish and The Bear’s favourite watering can, which I’d brought inside and placed on a sheet of newspaper in the hope that its presence might comfort him. Each of the cats took turns to do that thing cats always do in a new house, where they seem to be checking all the walls for secret passageways and weak spots, but none of them seemed unusually agitated. I would keep them in for a few days, but probably not much longer. I was massively grateful that they’d been so well behaved throughout the move, since a last-minute feline-based panic would probably have been the thing that pushed events over the line separating ‘sketchily organised stress fest’ from ‘all-out disaster’. My decision to upgrade to the biggest van possible had turned out to be a small wise decision wrapped up inside a much larger unwise one: even with all that space, my recent pruning of possessions and Pat’s ace packing skills, we required seven journeys there and back in the van, stretched over three days, meaning I got it back to the depot with only moments to spare. Without us both working non-stop from the moment we woke up each day to the moment we dropped at night, the emergency arrival of my mum and dad and a little more help from my friends Drew and Andy, we wouldn’t have managed it.

‘Pat’s such a good pal, isn’t he, lending you a hand like that,’ my mum remarked later. ‘But I thought you said he was a big bloke. He didn’t seem all that big to me.’ Her comment said a lot about the state the move had left the two of us in: bedraggled, rain-lashed, windswept and crooked-backed. Pat might have made the sensible change from his cowboy boots into an old pair of Converse, but it was moving itself that had rendered him temporarily reduced in size. Afterwards, he and I agreed that we felt less like we’d hired a van than been repeatedly reversed over by one. As we leaned on the outside wall after it was all over, surrounded by broken lamp shards, comparing our bruises, we felt all of our combined seventy-nine and a half years.

‘I was thinking,’ said Pat, taking a much-needed swig of Peroni. ‘It’s a good job you didn’t get that goat.’

* * *

If anything, the steamrollered feeling became even more extreme the following day, when everyone had gone. I was limping slightly from slipping on some wet leaves while carrying a heavy plant pot the previous afternoon, I could feel a cold coming on, my head felt like someone had jammed it full of old cotton wool and lint in the night and every time I turned around, my hip made an odd, tiny clicking sound, like I’d left a loose button somewhere in the bone’s cavity. After all the work of the last few months, a sensible person would probably have taken the opportunity to spend the day in bed recovering but, not being a sensible person, I chose instead to climb a ladder and put twenty-five heavy boxes of books and old magazines in the loft, assemble two large items of flat-pack furniture, then go straight out into Norwich and, accompanied by my friend Louise and some strangers, drink five pints of beer on an empty stomach. My main memory of the hours after that are of being carried aloft through Norwich city centre by two people I’d met just two hours previously, then getting woken up first thing the next morning by a carpenter who, in a rare moment of thoughtful planning, I’d booked to fit my new microchip cat flap. The carpenter was polite enough not to comment on my appearance, though he must have been slightly confused, since Halloween was still a full week and a half away.

Physically, I felt even worse than the day before but, as I said goodbye to the carpenter, this was offset by a gradually dawning relief: my old house, such a millstone to me for so long, was sold, the new one was in a passable state for when Gemma arrived back from Devon the following day, the cats would soon be going out and exploring and I could at last permit myself to relax. I’d just empty the cat litter, I decided, then head back to bed with a book.

People talk the big talk about uranium and lead but, as anyone who’s ever bagged it up knows, the world’s heaviest substance is actually used cat litter. This is generally OK if you’re feeling strong and have a hard-wearing bin liner, but somewhat less OK if, like me on this particular morning, you were feeling about as tough as a newborn foal and had just lazily grabbed a value Morrisons refuse sack that you’d previously used to transport some cushions in a house move. The next twenty-five seconds played out like some kind of ‘What Not To Do When You’ve Just Moved House With Cats’ public information video, the only missing bits being the giant neon flashing exclamation marks as each of my mistakes occurred: the open door left behind me as I walked barefoot across the drive; the bag splitting and spilling its contents; Shipley shooting through the gap behind me, me diving for him, missing and ripping a strip of skin off my arm on the cold, wet concrete; the door blowing shut behind me; the terror on my face as I heard the click of its Yale lock and felt in the pocket of my pyjama bottoms for a non-existent key.

Being ‘the new person with four cats’, I’d hoped to be able to present myself for the first time to my next-door neighbour in a respectable sort of way, and so turning up on her doorstep clad only in pyjama bottoms and an old, ripped Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers T-shirt telling wild-eyed tales of a lost feline wasn’t exactly what you’d call ideal. I was, however, fortunate on two counts: first, Vivian, who lived in the house to the left of the bungalow, was at home in my hour of need; second, she was extremely kind, putting the kettle on, offering me a towel to dry my feet, letting me borrow her landline to call a locksmith and lending me some shoes. Due to go out shortly, she even trustingly offered to let me stay in her house on my own while I waited for a stranger to come and break into mine, but, feeling I’d imposed more than enough already, I declined, thanked her for her hospitality and trudged back in the direction of the waste ground I’d seen Shipley heading towards.

To be honest, I wasn’t overly worried about Shipley. I knew him well enough to understand that he was very unlikely to get lost, even in a new outdoor habitat. As my resident public relations cat, he would be only too keen to get back to his new central office and catch up on correspondence. Sure enough, after a couple of whistles and an encouraging but slightly nervous responding profanity, I located him cowering behind a broken fence panel, scooped him up and headed back to the front door. Vivian, it turned out, had relatively large feet and, though her shoes were a couple of sizes too small for me, I found that I could walk in them easily enough. I wondered about taking them off before the locksmith arrived but, on further consideration, decided against it. It looked like it was about to rain and, within the context of the indignities of the last few days, the idea of a potentially manly stranger seeing me wearing pyjamas and the shoes of a woman twenty-five years my senior didn’t really seem that much of a big deal.

I’d not programmed Shipley’s microchip number into the cat flap as yet, so the two of us hunkered down on the concrete, out of the wind. Shipley soon got comfortable in his favourite upside-down position on my lap and began a possessive, industrial purr. After ten minutes, a tabby cat I’d never seen before – lean, short-haired and muscular – prowled into the driveway and began to sniff some of the scattered cat litter. I called to him, but in language even Shipley deemed shocking, he told me to get lost then jogged off in the direction of Vivian’s front garden. A couple of minutes after that, the rain started, and all there was left for us to do was wait.