Jeolla

Highlights

Hyangiram A tiny hermitage hanging onto cliffs south of Yeosu, and the best place in the country in which to see in the New Year.

Mokpo This characterful seaside city is the best jumping-off point for excursions to the emerald isles of the West Sea.

Naejangsan The circular mountain ridge within this national park looks stunning in autumn, and is the best place in the land to enjoy the season.

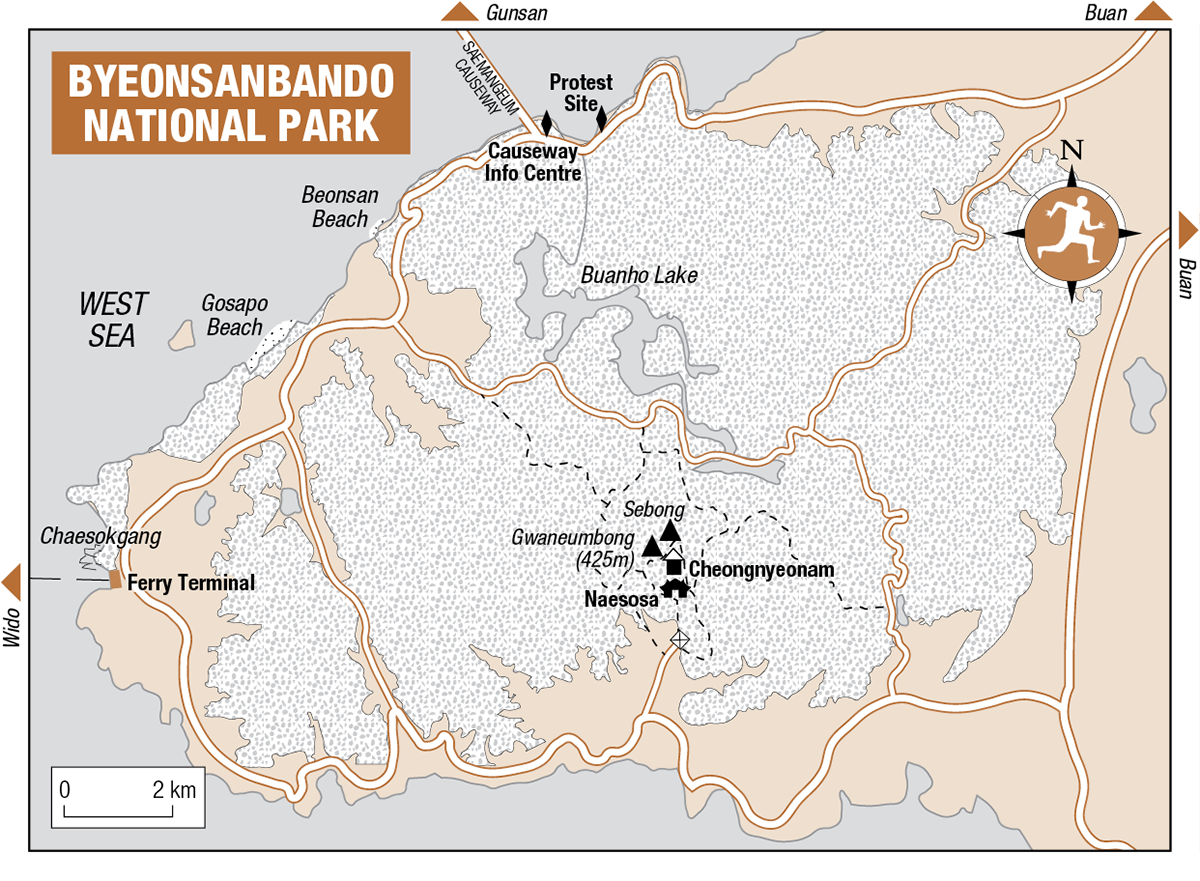

Byeonsanbando Look out across the sea from the peaks of this peninsular national park, then descend to the coast at low tide to see some terrific cliff formations.

Jeonju’s hanok village There are all sorts of traditional sights and activities to pursue in this wonderful area of hanok housing.

Food Jeollanese cuisine offers the best ingredients and more side dishes, and is best exemplified by Jeonju’s take on bibimbap.

Tapsa This cute temple, nestling in between the “horse-ear” peaks of Maisan Provincial Park, is surrounded by gravity-defying towers of hand-stacked rock.

If you’re after top-notch food, craggy coastlines, vistas of undulating green fields, and islands on which no foreigner has ever set foot, go no further. Jeju Island has its rock formations and palm trees, and Gangwon-do pulls in nature-lovers by the truckload, but it’s the Jeolla provinces ( ) where you’ll find the essence of Korea at its most potent – a somewhat ironic contention since the Jeollanese have long played the role of the renegade. Here, the national inferiority complex that many foreigners diagnose in the Korean psyche is compounded by a regional one: this is the most put-upon part of a much put-upon country. Although the differences between Jeolla and the rest of the country are being diluted daily, they’re still strong enough to help make it the most distinctive and absorbing part of the mainland.

) where you’ll find the essence of Korea at its most potent – a somewhat ironic contention since the Jeollanese have long played the role of the renegade. Here, the national inferiority complex that many foreigners diagnose in the Korean psyche is compounded by a regional one: this is the most put-upon part of a much put-upon country. Although the differences between Jeolla and the rest of the country are being diluted daily, they’re still strong enough to help make it the most distinctive and absorbing part of the mainland.

The Korean coast dissolves into thousands of islands, the majority of which lie sprinkled like confetti in Jeollanese waters. Some such as Hongdo and Geomundo are popular holiday resorts, while others lie in wave-smashed obscurity, their inhabitants hauling their living from the sea and preserving a lifestyle little changed in decades. The few foreign visitors who make it this far find that the best way to enjoy the area is to pick a ferry at random, and simply go with the flow.

In addition, Jeollanese cuisine is the envy of the nation – pride of place on the regional menu goes to Jeonju bibimbap, a local take on one of Korea’s favourite dishes. Jeolla’s culinary reputation arises from its status as one of Korea’s main food-producing areas, with shimmering emerald rice paddies vying for space in and around the national parks. The Jeollanese people themselves are also pretty special – fiercely proud of their homeland, with a devotion born from decades of social and economic repression. Speaking a dialect sometimes incomprehensible to other Koreans, they revel in their outsider status, and make a credible claim to be the friendliest people in the country.

Most of the islands trace a protective arc around Jeonnam ( ), a province whose name translates as “South Jeolla”. On the map, this region bears a strong resemblance to Greece, and the similarities don’t end there; the region is littered with ports and a constellation of islands, their surrounding waters bursting with seafood. Low-rise buildings snake up from the shores to the hills, and some towns are seemingly populated entirely with salty old pensioners. Yeosu and Mokpo are relatively small, unhurried cities exuding a worn, brackish charm, while further inland is the region’s capital and largest city, Gwangju, a young, trendy metropolis with a reputation for art and political activism.

), a province whose name translates as “South Jeolla”. On the map, this region bears a strong resemblance to Greece, and the similarities don’t end there; the region is littered with ports and a constellation of islands, their surrounding waters bursting with seafood. Low-rise buildings snake up from the shores to the hills, and some towns are seemingly populated entirely with salty old pensioners. Yeosu and Mokpo are relatively small, unhurried cities exuding a worn, brackish charm, while further inland is the region’s capital and largest city, Gwangju, a young, trendy metropolis with a reputation for art and political activism.

The same can be said for likeable Jeonju, capital of Jeonbuk ( ; “North Jeolla”) province to the north and one of the most inviting cities in the land; its hanok district of traditional buildings is a particular highlight. Green and gorgeous, Jeonbuk is also home to four excellent national parks, where most of the province’s visitors head; in addition, the arresting “horse-ear” mountains of Maisan Provincial Park accentuate the appeal of Tapsa, a glorious temple that sits in between its distinctive twin peaks.

; “North Jeolla”) province to the north and one of the most inviting cities in the land; its hanok district of traditional buildings is a particular highlight. Green and gorgeous, Jeonbuk is also home to four excellent national parks, where most of the province’s visitors head; in addition, the arresting “horse-ear” mountains of Maisan Provincial Park accentuate the appeal of Tapsa, a glorious temple that sits in between its distinctive twin peaks.

Jeolla’s gripe with the rest of the country is largely political. Despite its status as the birthplace of the Joseon dynasty that ruled Korea from 1392 until its annexation by the Japanese in 1910, most of the country’s leaders since independence in 1945 have hailed from the southeastern Gyeongsang provinces. Seeking to undermine their Jeollanese opposition, the central government deliberately withheld funding for the region, leaving its cities in relative decay while the country as a whole reaped the benefits of the “economic miracle”. Political discord reached its nadir in 1980, when the city of Gwangju was the unfortunate location of a massacre which left hundreds of civilians dead. National democratic reform was gradually fostered in the following years, culminating in the election of Jeolla native and eventual Nobel Peace Prize laureate Kim Dae-jung. Kim attempted to claw his home province’s living standards up to scratch with a series of big-money projects, notably in the form of highway connections to the rest of the country once so conspicuous by their absence. Despite these advances, with the exception of Gwangju and Jeonju, Jeolla’s urban centres are still among the poorest places in Korea.

Charming in an offbeat way, YEOSU ( ) is by far the most appealing city on Jeonnam’s south coast. Ferries once sailed from here to Jeju, but though these have been discontinued there’s more than enough here to eat up a whole day of sightseeing. It’s beautifully set in a ring of emerald islands, so the wonderful views over the South Sea alone would justify a trip down the narrow peninsula. Though parts of the coast remain rugged and pristine, the area around Yeosu has been heavily industrialized, especially the gigantic factory district to the city’s north, and consequently many of Yeosu’s few foreign visitors are here on business. However, in 2012 Yeosu plays host to an international Expo, an event that could put the city firmly, and deservedly, back on the tourist map.

) is by far the most appealing city on Jeonnam’s south coast. Ferries once sailed from here to Jeju, but though these have been discontinued there’s more than enough here to eat up a whole day of sightseeing. It’s beautifully set in a ring of emerald islands, so the wonderful views over the South Sea alone would justify a trip down the narrow peninsula. Though parts of the coast remain rugged and pristine, the area around Yeosu has been heavily industrialized, especially the gigantic factory district to the city’s north, and consequently many of Yeosu’s few foreign visitors are here on business. However, in 2012 Yeosu plays host to an international Expo, an event that could put the city firmly, and deservedly, back on the tourist map.

Despite Yeosu’s sprawling size, many of its most interesting sights are just about within walking distance of each other in and around the city centre. These include Odongdo, a bamboo-and-pine island popular with families, and a replica of Admiral Yi’s famed turtle ship. Beyond the city limits are the black-sand beach of Manseongni, and Hyangiram, a magical hermitage at the end of the Yeosu peninsula.

Admiral Yi, conqueror of the seas

“…it seems, in truth, no exaggeration to assert that from first to last he never made a mistake, for his work was so complete under each variety of circumstances as to defy criticism.”

Admiral George Alexander Ballard, The Influence of the Sea on the Political History of Japan

Were he not born during the Joseon dynasty, a period in which a nervous Korea largely shielded itself from the outside world, it is likely that Admiral Yi Sun-shin (

; 1545–98) would today be ranked alongside Napoleon and Horatio Nelson as one of the greatest generals of all time. A Korean national hero, you’ll see his face on the W100 coin, and statues of the great man dot the country’s shores. The two most pertinent are at Yeosu, where he was headquartered, and Tongyeong (then known as Chungmu), the site of his most famous victory.

; 1545–98) would today be ranked alongside Napoleon and Horatio Nelson as one of the greatest generals of all time. A Korean national hero, you’ll see his face on the W100 coin, and statues of the great man dot the country’s shores. The two most pertinent are at Yeosu, where he was headquartered, and Tongyeong (then known as Chungmu), the site of his most famous victory.

Yi Sun-shin was both a beneficiary and a victim of circumstance. A year after his first major posting as Naval Commander of Jeolla in 1591, there began a six-year wave of Japanese invasions. Although the Nipponese were setting their sights on an eventual assault on China, Korea had the misfortune to be in the way and loyal to the Chinese emperor, and 150,000 troops laid siege to the country. Admiral Yi achieved a string of well-orchestrated victories, spearheaded by his famed turtle ships, vessels topped with iron spikes that were adept at navigating the island-dotted waters with ease.

Despite his triumphs, the admiral fell victim to a Japanese spy and the workings of the Korean political system. A double agent persuaded a high-ranking Korean General that the Japanese would attack in a suspiciously treacherous area; seeing through the plan, Admiral Yi refused the General’s orders, and as a result was stripped of his duties and sent to Seoul for torture. His successor, Won Gyeun, was far less successful, and within months had been killed by the Japanese after managing to lose the whole Korean fleet, bar twelve warships. Yi was hastily reinstated, and after hunting down the remaining ships managed to repel a Japanese armada ten times more numerous. Peppering the enemy’s vessels with cannonballs and flaming arrows, Yi waited for the tide to change and rammed the tightly packed enemy ships into one another. Heroic to the last, Yi was killed by a stray bullet as the Japanese retreated from what was to be the final battle of the war, apparently using his final gasps to insist that his death be kept secret until victory had been assured.

Arrival and information

The new airport lies around 20km to the north – take a bus from the city’s main bus terminal – and has flights to and from Seoul and Jeju Island. Buses and trains arriving into Yeosu squeeze down the narrow isthmus, which opens out as it hits the city; both stations are located frustratingly far from the action. A number of bus routes head into the centre from both, but you’ll barely pay any more in a taxi (W4000 or so).

The ferry terminal, on the other hand, is in an area bristling with shops and motels. This is Yeosu’s heart, with plenty of raw fish restaurants and markets, and many of the city’s best sights within walking distance. From around the ferry terminal you’ll see the triangular red masts of Dolsan Bridge, which connects the city to the island of Dolsando. For a city of Yeosu’s size, good travel information is hard to come by, with the only decent point being a small booth near the entrance to Odongdo.

Accommodation

You’ll find motels near all of Yeosu’s main travel junctions, but due to the out-of-the-way location of the bus terminal and the seedy environs of the train station it’s best to head to the ferry area. Do note that foreigners are regularly quoted inflated prices here – but haggle hard, hunt around, and you should be able to find a room for W30,000 or less. Those aiming even lower on the price scale – or just in need of a good wash after spending time on the Jeonnam coast – should head to the jjimjilbang on the shore near Admiral Yi’s turtle ship, on the way to Hyangiram, which offers excellent sea views from some of its pool rooms. Lastly, a few new top-end options should have opened up by the time Expo 2012 kicks off.

Daia Motel  Gyodong

Gyodong  061/663-3347. Near the ferry terminal, this motel is just down the road from the Midojang, but the rooms are slightly plusher, and the prices accordingly higher.

061/663-3347. Near the ferry terminal, this motel is just down the road from the Midojang, but the rooms are slightly plusher, and the prices accordingly higher.

Golden Park Hotel Sujeondong  061/665-400. Poky ondol rooms make this more of a motel than a hotel, though it’s a good option on the entrance road to Odongdo, and is also within walking distance of the train station.

061/665-400. Poky ondol rooms make this more of a motel than a hotel, though it’s a good option on the entrance road to Odongdo, and is also within walking distance of the train station.

Midojang  Gyodong. This downtown motel, within a few minutes’ walk of the ferry terminal, has perfectly acceptable rooms with private facilities. The owners offer slight discounts to foreigners.

Gyodong. This downtown motel, within a few minutes’ walk of the ferry terminal, has perfectly acceptable rooms with private facilities. The owners offer slight discounts to foreigners.

Mobeom Yeoinsuk  Ferry terminal area

Ferry terminal area  061/663-4897. Just one of a clutch of yeoinsuk in a pleasantly brackish area opposite the ferry terminal, this is a friendly, family-run place with dirt-cheap rooms.

061/663-4897. Just one of a clutch of yeoinsuk in a pleasantly brackish area opposite the ferry terminal, this is a friendly, family-run place with dirt-cheap rooms.

Yeosu Beach Hotel Chungmudong  061/663-2011. Yeosu’s best hotel has cosy rooms with great showers, and is just a short walk from the main shopping area. A popular choice with Korean honeymooners (though less so since the ferries to Jeju stopped), it has a decent on-site restaurant and café, and offers airport pick-up. Ask about discounts off-season – usually around thirty percent.

061/663-2011. Yeosu’s best hotel has cosy rooms with great showers, and is just a short walk from the main shopping area. A popular choice with Korean honeymooners (though less so since the ferries to Jeju stopped), it has a decent on-site restaurant and café, and offers airport pick-up. Ask about discounts off-season – usually around thirty percent.

The City

For many visitors the real joys of Yeosu can be found wandering around the city’s many fish markets. However, the centre is home to a cache of interesting, unassuming sights. In the very centre of town, and just ten minutes’ walk northeast of the ferry terminal, is Jinnamgwan ( ), a pavilion once used as a guesthouse by the Korean navy. The site had previously been a command post of national hero Admiral Yi, but a guesthouse was built here in 1599, a year after his death, and replaced by the current structure in 1718. At 54m long and 14m high it’s the country’s largest single-storey wooden structure. In front of the guesthouse is a stone man – initially one of a group of seven – that was used as a decoy in the 1592–98 Japanese invasions. Just below the pavilion is a small museum (Tues–Sun 9am–6pm; free) detailing the area’s maritime fisticuffs.

), a pavilion once used as a guesthouse by the Korean navy. The site had previously been a command post of national hero Admiral Yi, but a guesthouse was built here in 1599, a year after his death, and replaced by the current structure in 1718. At 54m long and 14m high it’s the country’s largest single-storey wooden structure. In front of the guesthouse is a stone man – initially one of a group of seven – that was used as a decoy in the 1592–98 Japanese invasions. Just below the pavilion is a small museum (Tues–Sun 9am–6pm; free) detailing the area’s maritime fisticuffs.

A statue of Admiral Yi stands to the east of the city centre, on a hill overlooking the small island of Odongdo ( ; daily 9am–6pm; W1600). Essentially a botanical garden, it’s crisscrossed by a deliciously scented network of pine- and bamboo-lined paths, and has become a popular picnicking destination for local families. A 700m-long causeway connects it to the mainland, and if you don’t feel like walking you can hop on the bus – resembling a train – for a small fee. The island’s paths snake up to a lighthouse, the view from which gives a far clearer rendition of Yeosu’s surroundings than can be had from Jinnamgwan in the city centre. In the summer, kids love to cool off in the fountain by the docks on the northern shore – the water show comes on every twenty minutes or so. A number of boat tours operate from Odongdo – operators are unlikely to speak English, so these are best arranged through the tourist information centre outside the main entrance; routes include cruises across the harbour to Dolsan Bridge, and a longer haul to Hyangiram and back. At the time of writing, the island was off-limits thanks to construction work on the new Expo 2012 site. This is set to feature all sorts of futuristic pavilions, as well as a digital gallery and a “Sky Tower”; see

; daily 9am–6pm; W1600). Essentially a botanical garden, it’s crisscrossed by a deliciously scented network of pine- and bamboo-lined paths, and has become a popular picnicking destination for local families. A 700m-long causeway connects it to the mainland, and if you don’t feel like walking you can hop on the bus – resembling a train – for a small fee. The island’s paths snake up to a lighthouse, the view from which gives a far clearer rendition of Yeosu’s surroundings than can be had from Jinnamgwan in the city centre. In the summer, kids love to cool off in the fountain by the docks on the northern shore – the water show comes on every twenty minutes or so. A number of boat tours operate from Odongdo – operators are unlikely to speak English, so these are best arranged through the tourist information centre outside the main entrance; routes include cruises across the harbour to Dolsan Bridge, and a longer haul to Hyangiram and back. At the time of writing, the island was off-limits thanks to construction work on the new Expo 2012 site. This is set to feature all sorts of futuristic pavilions, as well as a digital gallery and a “Sky Tower”; see  www.expo2012.or.kr for more information.

www.expo2012.or.kr for more information.

To the south and across Dolsan Bridge is a replica of Admiral Yi’s turtle ship (daily 8am–6pm; W1200), a small, rounded vessel with a wooden dragon head at the front. Such boats spearheaded the battles against the Japanese in the sixteenth century, and were so-called because they were tough to attack from the top, due to the iron roof covered with spiked metal. Inside the replica is a modern-day regiment of mannequins; the exterior is decidedly more interesting.

Eating and drinking

Yeosu’s restaurants are surprisingly poor by Jeolla standards. If you’re feeling brave, and have a decent command of Korean seafood menus, you will find that the canalside fish market north of the ferry terminal has a wealth of choice, as does Raw Fish Town – a parade of restaurants near Admiral Yi’s turtle ship. Prices at the latter aren’t cheap, and establishments cater for groups rather than solo travellers – large spreads are the order of the day (figure on paying W30,000 or more for a meal). Alternatively there’s Hemingway ( ), near Dolsan Bridge, which serves passable steak and pork cutlet dishes with splendid views back over the city. The shopping area has a lot of grimy Korean fast food dens but Sinpo Woori Mandoo (

), near Dolsan Bridge, which serves passable steak and pork cutlet dishes with splendid views back over the city. The shopping area has a lot of grimy Korean fast food dens but Sinpo Woori Mandoo ( ) stands out, and has an English-language picture menu to boot.

) stands out, and has an English-language picture menu to boot.

The downtown area is quiet even on weekend evenings, although on a warm night it’s hard to beat a bottle of beer or makkeolli on the harbour front – take your pick from a number of convenience stores. For a night out you’re much better off heading to the new area west of the centre called Hakdong ( ), though it’s over half an hour away by bus, and expensive to reach by taxi. Here, the expat-friendly bars Elle Lui and Lost Shepherd Girl (also known as LSG) continue to get good reviews.

), though it’s over half an hour away by bus, and expensive to reach by taxi. Here, the expat-friendly bars Elle Lui and Lost Shepherd Girl (also known as LSG) continue to get good reviews.

Manseongni

Around 4km north up the coast from Yeosu’s train station, you’ll find minbak and raw fish restaurants aplenty at Manseongni ( ), which is revered as the only black sand beach on the Korean mainland – in truth, this volcanic material is actually rather grey in appearance. Mid-April is said to be the time of year when the beach “opens its eyes”, and people flock to bury themselves in the allegedly nutritious sand, an experience somewhat akin to being a cigarette butt for the day. Other sights of note lie on the mess of islands south of Yeosu.

), which is revered as the only black sand beach on the Korean mainland – in truth, this volcanic material is actually rather grey in appearance. Mid-April is said to be the time of year when the beach “opens its eyes”, and people flock to bury themselves in the allegedly nutritious sand, an experience somewhat akin to being a cigarette butt for the day. Other sights of note lie on the mess of islands south of Yeosu.

Dadohae Haesang National Park

South of the city centre, the mainland soon melts into a host of islands, many of which lie under the protective umbrella of Dadohae Haesang National Park (

). Many can be accessed from Yeosu’s ferry terminal, and as with Jeolla’s other island archipelagos, these are best explored with no set plan. Dolsando (

). Many can be accessed from Yeosu’s ferry terminal, and as with Jeolla’s other island archipelagos, these are best explored with no set plan. Dolsando ( ), connected to the mainland by road, is the most visited and most famed for Hyangiram, a hermitage dangling over the crashing seas. Further south are Geumodo (

), connected to the mainland by road, is the most visited and most famed for Hyangiram, a hermitage dangling over the crashing seas. Further south are Geumodo ( ), a rural island fringed by rugged cliffs and rock faces, and Geomundo (

), a rural island fringed by rugged cliffs and rock faces, and Geomundo ( ), far from Yeosu – and briefly occupied by Britain during the 1880s, during an ill-planned stab at colonizing Korea’s southern coast – but now an increasingly popular holiday destination. From Geomundo you can take a tour boat around the assorted spires of rock that make up Baekdo (

), far from Yeosu – and briefly occupied by Britain during the 1880s, during an ill-planned stab at colonizing Korea’s southern coast – but now an increasingly popular holiday destination. From Geomundo you can take a tour boat around the assorted spires of rock that make up Baekdo ( ), a protected archipelago containing a number of impressive formations.

), a protected archipelago containing a number of impressive formations.

Clinging to the cliffs at the southeastern end of Dolsando is the magical hermitage of Hyangiram ( ; daily pre-dawn to 8pm; W2000), an eastward-facing favourite of sunrise seekers and a popular place to ring in the New Year. Behind Hyangiram is a collection of angular boulders which – according to local monks – resembles an oriental folding screen, and is soaked with camellia blossom in the spring. To get to Hyangiram, take a local bus from Yeosu’s city centre – #111 also runs directly from the train station and Odongdo. Although the trip can take around an hour, on a bumpy, winding course, the journey costs just W1000. Outside the hermitage is a small town of motels and restaurants – Hwangtobang (

; daily pre-dawn to 8pm; W2000), an eastward-facing favourite of sunrise seekers and a popular place to ring in the New Year. Behind Hyangiram is a collection of angular boulders which – according to local monks – resembles an oriental folding screen, and is soaked with camellia blossom in the spring. To get to Hyangiram, take a local bus from Yeosu’s city centre – #111 also runs directly from the train station and Odongdo. Although the trip can take around an hour, on a bumpy, winding course, the journey costs just W1000. Outside the hermitage is a small town of motels and restaurants – Hwangtobang ( 061/644-4353;

061/644-4353;  ), near the entrance, offers both of these as well as a café, though other motels have better sea views.

), near the entrance, offers both of these as well as a café, though other motels have better sea views.

Yeosu to Mokpo

The large coastal cities of Yeosu and Mokpo are connected by road, though in the summer it’s possible to travel between them by ferry – a beautiful journey that jets passengers past whole teams of islands. Travelling overland, you’ll pass Jogyesan, a provincial park home to two gorgeous temples; the tea plantation at Boseong; and the bald crags of Wolchulsan National Park, just outside Mokpo. Also in the Mokpo area are a couple of charming islands – Jindo, famed for its indigenous breed of dog, and Wando, home to a curious “miracle”.

Jogyesan Provincial Park

The small but pretty JOGYESAN PROVINCIAL PARK is flanked by two splendid temples, Seonamsa and Songgwangsa. If you get up early enough, it’s possible to see both temples in a single day, taking either the hiking trail that runs between them or one of the buses that heads the long way around the park. The park and its temples are accessible by bus from SUNCHEON ( ), an otherwise uninteresting city that’s easy to get to by bus, and occasionally train, from elsewhere in the area.

), an otherwise uninteresting city that’s easy to get to by bus, and occasionally train, from elsewhere in the area.

Practicalities

The simplest way to get to the park is on one of the tour buses that leave from outside Suncheon’s train station every day at 9.50am. As well as Seonamsa temple, tours take in a film set on which historical dramas are regularly shot, and the interesting Nagan folk village, set within authentic Jeoson fortress walls and a pleasingly rural place to stay. On weekends, another tour bus leaves at 9.40am, though it goes to Songgwangsa temple, rather than Seonamsa.

To get to the park on public transport, take bus #1 from central Suncheon to Seonamsa, or #111 to Songgwangsa. Both buses take an hour or so, and if moving between the two you’ll save a lot of time by transferring at Seopyeong-maeul, a small village near Seonamsa, where the bus routes split. Also note that there are occasional buses to Songgwangsa from Gwangju. The paucity of buses to the park means that you may have to overnight in Suncheon; if so, head for the district of Yeonhyangdong ( ), which has plenty of motels and restaurants.

), which has plenty of motels and restaurants.

There are also low-key accommodation and restaurant facilities at both entrances to the park; minbak offer the most authentic Korean experience, but for a little more comfort try Saejogyesan-jang ( ;

;  061/751-9200;

061/751-9200;  ) outside the Seonamsa entrance. The restaurants outside Songgwangsa are in traditionally styled buildings; Suncheon Sikdang (

) outside the Seonamsa entrance. The restaurants outside Songgwangsa are in traditionally styled buildings; Suncheon Sikdang ( ) deserves a mention, if only for the charming way in which its name has been spelled out in Korean. As in many Korean rural areas, sanchae bibimbap (

) deserves a mention, if only for the charming way in which its name has been spelled out in Korean. As in many Korean rural areas, sanchae bibimbap ( ) is a favoured dish, and is made with local ingredients.

) is a favoured dish, and is made with local ingredients.

Seonamsa

Seonamsa ( ), on the park’s eastern side, is the closer temple of the two to Suncheon. On the way in from the ticket booth you’ll pass Seungsongyo, an old rock bridge; its semicircular lower arch makes a full disc when reflected in the river below: slide down to the water to get the best view. There has been a temple here since 861 – the dawn of the Unified Silla period – but having fallen victim to fire several times, the present buildings are considerably more modern. The temple is apparently too poor to afford a full-scale refurbishment, but provides a pleasant visit as a result, despite the fact that a couple of the once-meditative ponds have been carelessly lined with concrete. Its entrance gate is ageing gracefully, though the dragon heads are a more recent addition – the original smaller, stealthier-looking ones can be found in the small museum inside. Notably, the temple eschews the usual four heavenly guardians at the entrance, relying instead on the surrounding mountains for protection, which look especially imposing on a rainy day. The main hall in the central courtyard is also unconventional, with its blocked central entrance symbolically allowing only Buddhist knowledge through, and not even accessible to high-ranking monks – this is said to represent the egalitarian principles of the temple. The hall was apparently built without nails, and at the back contains a long coffin-like box which holds a large picture of the Buddha that was once unfurled during times of drought, to bring rain to the crops. A smaller version of this picture hangs over the box. Around the complex are a number of small paths, one leading to a pair of majestic stone turtles; the one on the right-hand side is crowned by an almost Moorish clutch of twisting dragons. Another path fires west across the park to Songgwangsa, a four-hour walk, more if you scale Janggunbong (885m), the main peak, on the way.

), on the park’s eastern side, is the closer temple of the two to Suncheon. On the way in from the ticket booth you’ll pass Seungsongyo, an old rock bridge; its semicircular lower arch makes a full disc when reflected in the river below: slide down to the water to get the best view. There has been a temple here since 861 – the dawn of the Unified Silla period – but having fallen victim to fire several times, the present buildings are considerably more modern. The temple is apparently too poor to afford a full-scale refurbishment, but provides a pleasant visit as a result, despite the fact that a couple of the once-meditative ponds have been carelessly lined with concrete. Its entrance gate is ageing gracefully, though the dragon heads are a more recent addition – the original smaller, stealthier-looking ones can be found in the small museum inside. Notably, the temple eschews the usual four heavenly guardians at the entrance, relying instead on the surrounding mountains for protection, which look especially imposing on a rainy day. The main hall in the central courtyard is also unconventional, with its blocked central entrance symbolically allowing only Buddhist knowledge through, and not even accessible to high-ranking monks – this is said to represent the egalitarian principles of the temple. The hall was apparently built without nails, and at the back contains a long coffin-like box which holds a large picture of the Buddha that was once unfurled during times of drought, to bring rain to the crops. A smaller version of this picture hangs over the box. Around the complex are a number of small paths, one leading to a pair of majestic stone turtles; the one on the right-hand side is crowned by an almost Moorish clutch of twisting dragons. Another path fires west across the park to Songgwangsa, a four-hour walk, more if you scale Janggunbong (885m), the main peak, on the way.

To the west of the park is Songgwangsa ( ), viewed by Koreans as one of the most important temples in the country, and is one of the “Three Jewels” of Korean Buddhism – the others are Tongdosa and Haeinsa. Large, well maintained and often full of devotees, it may disappoint those who’ve already appreciated the earthier delights of Seonamsa. The temple is accessed on a peculiar bridge-cum-pavilion, beyond which can be found the four guardians that were conspicuously absent at Seonamsa. Within the complex is Seungbojeon, a hall filled with 1250 individually sculpted figurines, the painstaking attention to detail echoed in the paintwork of the main hall; colourful and highly intricate patterns spread like a rash down the pillars, surrounding a trio of Buddha statues representing the past, present and future. Unfortunately, the Hall of National Teachers is closed to the public – perhaps to protect its gold-fringed ceiling.

), viewed by Koreans as one of the most important temples in the country, and is one of the “Three Jewels” of Korean Buddhism – the others are Tongdosa and Haeinsa. Large, well maintained and often full of devotees, it may disappoint those who’ve already appreciated the earthier delights of Seonamsa. The temple is accessed on a peculiar bridge-cum-pavilion, beyond which can be found the four guardians that were conspicuously absent at Seonamsa. Within the complex is Seungbojeon, a hall filled with 1250 individually sculpted figurines, the painstaking attention to detail echoed in the paintwork of the main hall; colourful and highly intricate patterns spread like a rash down the pillars, surrounding a trio of Buddha statues representing the past, present and future. Unfortunately, the Hall of National Teachers is closed to the public – perhaps to protect its gold-fringed ceiling.

The town of BOSEONG ( ) is famed for the tea plantations that surround it; visitors flock here during warmer months to take pictures of the thousands of tea trees that line the slopes. They may not be as busy or as verdant as those in Sri Lanka or Laos, for example, but they’re still a magnificent sight, particularly when sepia-tinged on early summer evenings. Pluckers comb the well-manicured rows at all times of year, though spring is the main harvest season, and if you’re lucky you may be able to see the day’s take being processed in the on-site factory. Green tea (

) is famed for the tea plantations that surround it; visitors flock here during warmer months to take pictures of the thousands of tea trees that line the slopes. They may not be as busy or as verdant as those in Sri Lanka or Laos, for example, but they’re still a magnificent sight, particularly when sepia-tinged on early summer evenings. Pluckers comb the well-manicured rows at all times of year, though spring is the main harvest season, and if you’re lucky you may be able to see the day’s take being processed in the on-site factory. Green tea ( ; nok-cha) rode the crest of the “healthy living” wave that swept the country in the early 2000s, and here you can imbibe the leaf in more ways than you could ever have imagined. A couple of on-site restaurants serve up green tea chicken cutlet, green tea bibimbap and green tea with seafood on rice, as well as a variety of dishes featuring pork from pigs raised on a green tea diet. There’s also a café serving nok-cha ice cream and snacks – if you’ve never tried a nok-cha latte, you’ll never get a better opportunity (though, admittedly, it’s on sale at pretty much every café up to the North Korean border).

; nok-cha) rode the crest of the “healthy living” wave that swept the country in the early 2000s, and here you can imbibe the leaf in more ways than you could ever have imagined. A couple of on-site restaurants serve up green tea chicken cutlet, green tea bibimbap and green tea with seafood on rice, as well as a variety of dishes featuring pork from pigs raised on a green tea diet. There’s also a café serving nok-cha ice cream and snacks – if you’ve never tried a nok-cha latte, you’ll never get a better opportunity (though, admittedly, it’s on sale at pretty much every café up to the North Korean border).

Daehan Dawon ( ; daily: summer 5am–8pm; winter 8am–6pm; W1600) is the main plantation; to get here on public transport you’ll first need to head to Boseong itself. From there, head coastward on one of the half-hourly buses to Yulpo, and get off at the tea plantation – let the driver know where you’re going. Further up the same road are a few less-visited plantations that can be entered for free, one of which stretches down to a cute village by the water’s edge.

; daily: summer 5am–8pm; winter 8am–6pm; W1600) is the main plantation; to get here on public transport you’ll first need to head to Boseong itself. From there, head coastward on one of the half-hourly buses to Yulpo, and get off at the tea plantation – let the driver know where you’re going. Further up the same road are a few less-visited plantations that can be entered for free, one of which stretches down to a cute village by the water’s edge.

A short bus-ride east of Mokpo, WOLCHULSAN NATIONAL PARK (

) is the smallest of Korea’s national parks and one of its least visited – the lack of historic temples and its difficult access are a blessing in disguise. Set within the achingly gorgeous Jeollanese countryside, Wolchulsan’s jumble of mazy rocks rises to more than 800m above sea level, casting jagged shadows over the rice paddies.

) is the smallest of Korea’s national parks and one of its least visited – the lack of historic temples and its difficult access are a blessing in disguise. Set within the achingly gorgeous Jeollanese countryside, Wolchulsan’s jumble of mazy rocks rises to more than 800m above sea level, casting jagged shadows over the rice paddies.

Just five buses a day make the fifteen-minute trip to the main entrance at Cheonhwangsaji from the small town of Yeong-am; alternatively, it’s an affordable taxi ride, or an easy walk. Yeong-am itself is well connected to Mokpo and Yeosu by bus. From here a short but steep hiking trail heads up to Cheonhwangbong (809m), the park’s main peak; along the way, you’ll have to traverse the “Cloud Bridge”, a steel structure slung between two peaks – not for vertigo sufferers. Views from here, or the peak itself, are magnificent, and with an early enough start it’s possible to make the tough hike to Dogapsa ( ), an uninteresting temple on the other side of the park, while heeding the “no shamanism” warning signs along the way. There’s no public transport to or from the temple, but a forty-minute walk south – all downhill – will bring you to Gurim (

), an uninteresting temple on the other side of the park, while heeding the “no shamanism” warning signs along the way. There’s no public transport to or from the temple, but a forty-minute walk south – all downhill – will bring you to Gurim ( ), a small village outside the park, on the main road between Mokpo and Yeong-am. A couple of kilometres south of Gurim is the Yeongam Pottery Centre (daily 9am–6pm; free). Due to the properties of the local soil, this whole area was Korea’s main ceramics hub throughout the Three Kingdoms period, and local artisans enjoyed trade with similarly minded folk in China and Japan. Sadly, the centre is as dull as the clay itself, though the on-site shop is good for souvenirs; you may get a chance to throw your own pot for a small fee, and there’s a decidedly brutalist sculpture outside the main entrance which would look at home in Pyongyang (were it not for the South Korean flag). The downhill walk from Gurim to the centre is much more interesting – the town remains an important base for pottery production, and accordingly many of its houses have eschewed modern-day metals for beautiful, traditional tiled roofs. There are few concessions to modern life here.

), a small village outside the park, on the main road between Mokpo and Yeong-am. A couple of kilometres south of Gurim is the Yeongam Pottery Centre (daily 9am–6pm; free). Due to the properties of the local soil, this whole area was Korea’s main ceramics hub throughout the Three Kingdoms period, and local artisans enjoyed trade with similarly minded folk in China and Japan. Sadly, the centre is as dull as the clay itself, though the on-site shop is good for souvenirs; you may get a chance to throw your own pot for a small fee, and there’s a decidedly brutalist sculpture outside the main entrance which would look at home in Pyongyang (were it not for the South Korean flag). The downhill walk from Gurim to the centre is much more interesting – the town remains an important base for pottery production, and accordingly many of its houses have eschewed modern-day metals for beautiful, traditional tiled roofs. There are few concessions to modern life here.

Wando

Dangling off Korea’s southwestern tip is a motley bunch of more than a hundred islands. The hub of this group and the most popular is WANDO ( ), owing to its connections to the mainland by bus and Jeju Island by sea. Wando also has plenty of diversions in its own right – a journey away from Wando-eup (

), owing to its connections to the mainland by bus and Jeju Island by sea. Wando also has plenty of diversions in its own right – a journey away from Wando-eup ( ), the main town, will give you a glimpse of Jeolla’s pleasing rural underbelly. Regular buses run from here to Gugyedeung (

), the main town, will give you a glimpse of Jeolla’s pleasing rural underbelly. Regular buses run from here to Gugyedeung ( ), a small, rocky beach in the coastal village of Jeongdo-ri, and to Cheonghaejin (

), a small, rocky beach in the coastal village of Jeongdo-ri, and to Cheonghaejin ( ), a stone park looking over a tiny islet which, despite its unassuming pastoral mix of farms and mud walls, was once important enough to send trade ships to China.

), a stone park looking over a tiny islet which, despite its unassuming pastoral mix of farms and mud walls, was once important enough to send trade ships to China.

Accommodation

In Wando-eup itself, most of the action is centred around the bus station, but the area around the main ferry terminal makes a quieter and more pleasant place to stay; Naju Yeoinsuk ( ;

;  ) has the cheapest rooms around, while Hilltop Motel (

) has the cheapest rooms around, while Hilltop Motel ( ) just behind it is for those who prefer to sleep on a bed rather than ondol flooring. Overlooking the sea between the two terminals is the pale yellow Dubai Motel (

) just behind it is for those who prefer to sleep on a bed rather than ondol flooring. Overlooking the sea between the two terminals is the pale yellow Dubai Motel ( 061/553-0688;

061/553-0688;  ), whose rooms are excellent value.

), whose rooms are excellent value.

Eating

There’s a fish market next to the ferry terminal, and plenty of restaurants serving both raw and cooked food. For something other than seafood, head a short way along the coast to Jjajjaru ( ), a Chinese restaurant offering huge two-person courses that could feed three or four.

), a Chinese restaurant offering huge two-person courses that could feed three or four.

Islands around Wando

Heading further afield, you’ll be spoilt for choice, with even the tiniest inhabited islands served by ferry from Wando-eup. Maps of the islands are available from the ferry terminal, where almost all services depart, with a few leaving from Je-il Mudu pier, a short walk to the north.

At the time of writing, Cheongsando ( ) was the island most visited by local tourists, mainly due to the fact that it was the scene of Spring Waltz, a popular drama series. Naturally spring is the busiest time of year here – and quite beautiful, with the island’s fields bursting with flowers. More beautiful is pine-clad Bogildo (

) was the island most visited by local tourists, mainly due to the fact that it was the scene of Spring Waltz, a popular drama series. Naturally spring is the busiest time of year here – and quite beautiful, with the island’s fields bursting with flowers. More beautiful is pine-clad Bogildo ( ), a well-kept secret accessible via a ferry terminal on the west of Wando island – free hourly shuttle-buses make the pretty twenty-minute journey from the bus terminal in Wando-eup. In the centre of tadpole-shaped Bogildo is a lake whose craggy tail, stretching east, has a couple of popular beaches.

), a well-kept secret accessible via a ferry terminal on the west of Wando island – free hourly shuttle-buses make the pretty twenty-minute journey from the bus terminal in Wando-eup. In the centre of tadpole-shaped Bogildo is a lake whose craggy tail, stretching east, has a couple of popular beaches.

Jindo

As the coast curls northwest towards Mokpo, the bewildering array of islands shows no sign of letting up. JINDO ( ), one of the most popular, is connected to the Korean mainland by road, but every year in early March the tides retreat to create a 3km-long land-bridge to a speck of land off the island’s eastern shore, a phenomenon that Koreans often compare to Moses’ parting of the Red Sea – this concept holds considerable appeal in an increasingly Christian country, and “Moses’ Miracle” persuades Koreans to don wellies and dash across in their tens of thousands. For the best dates to see this ask at any tourist board in the area, or call the national information line on

), one of the most popular, is connected to the Korean mainland by road, but every year in early March the tides retreat to create a 3km-long land-bridge to a speck of land off the island’s eastern shore, a phenomenon that Koreans often compare to Moses’ parting of the Red Sea – this concept holds considerable appeal in an increasingly Christian country, and “Moses’ Miracle” persuades Koreans to don wellies and dash across in their tens of thousands. For the best dates to see this ask at any tourist board in the area, or call the national information line on  1330. Visible throughout the year is the secluded temple of Ssanggyesa (

1330. Visible throughout the year is the secluded temple of Ssanggyesa ( ), which is best accessed by hourly bus (W1000) or taxi (W7000 from the bus terminal); if you’re choosing the latter option, arrange a pick-up time with your driver, or at least hang onto his business card.

), which is best accessed by hourly bus (W1000) or taxi (W7000 from the bus terminal); if you’re choosing the latter option, arrange a pick-up time with your driver, or at least hang onto his business card.

Jindu is also famed for the Jindo-gae, a white breed of dog with a distinctive curved tail; unique to the island, this species has been officially classified as National Natural Treasure #53. The mutts can be seen in their pens at a research centre – fifteen minutes’ walk from the bus terminal – which occasionally hosts short and unappealing dog shows, as well as a canine beauty pageant each autumn.

The island is accessible from Mokpo by both bus and ferry, with free shuttle buses from the terminal to the relevant stretch of coast during the annual parting of the seas.

The Korean peninsula has thousands of islands on its fringes, but the seas around the coastal city of MOKPO ( ) have by far the most concentrated number. Though many of these are merely bluffs of barnacled rock poking out above the West Sea (also known as the Yellow Sea), dozens are accessible by ferry from Mokpo; beautiful in an ugly kind of way, this curious city gives the impression that it would happily be an island if it could.

) have by far the most concentrated number. Though many of these are merely bluffs of barnacled rock poking out above the West Sea (also known as the Yellow Sea), dozens are accessible by ferry from Mokpo; beautiful in an ugly kind of way, this curious city gives the impression that it would happily be an island if it could.

Korea’s southwestern train line ends quite visibly in Mokpo city centre. The highway from the centre of the country does likewise with less fuss, but was not completed until fairly recently. For much of the 1970s and 1980s, public funding also ran out before it hit southern Jeolla – poor transport connections to the rest of the country are just one example of the way this area was neglected by the central government. For much of this time, the main opposition party was based in Mokpo, and funding was deliberately cut in an attempt to marginalize the city, which was once among the most populous and powerful in the land. Though the balance is now being addressed with a series of large projects, much of the city is still run-down, and Mokpo is probably the poorest urban centre in the country. Some Koreans say that taxi drivers are a good indicator of the wealth of the cities, and here cabbies have a habit of beeping at pedestrians in the hope that they want a lift, occasionally swinging around for a second go. Things are changing, however, especially in the new district of Hadang, which was built on land reclaimed from the sea, but it’ll be a while before Mokpo’s saline charms are eroded.

Mokpo is not the easiest Korean city in which to get your bearings. The most logical way to arrive is by train, as the main station is right next to a busy shopping area in the centre of the city; buses terminate some way to the north, just W5000 by taxi to the centre, to which several city bus routes also head (15min; W900). The most useful of these is #1, which passes both the bus and the train stations on its way to the huge new ferry terminal on the city’s southern shore, a lavishly funded structure standing incongruously in an area of apparent decay, and as such one of the most telling symbols of modern Mokpo. There are services to and from many islands in the West Sea, as well as Jeju Island, and occasionally Yeosu.

Although things should improve as the city grows, tourist information has never been one of Mokpo’s strong points; there’s a near-useless booth in the train station, and a small info-hut outside the Natural History museum.

Formula 1 comes to Mokpo

In 2010, the Formula 1 circus finally came to Korea, with the inaugural Grand Prix taking place at a brand-new track just east of Mokpo. The first hosting of this event was fraught with problems: the track was only given its safety certificate days before the race, spectator enclosures were hastily put together, and there were only three acceptable hotels in the whole of Mokpo. Most fans, and even some VIPs, were forced to stay at love hotels – one BBC journalist returned to her room to find that it had been used in her absence (a used contraceptive on the floor providing the evidence).

Race day itself was also memorable for the wrong reasons. Traffic jams resulting from poor access to the track meant that thousands of spectators arrived late – and in some cases, not at all. Rain didn’t help matters, with the newly built track stubbornly refusing to drain; concerns about driver safety led to the race being delayed for over an hour, and at one point the embarrassing possibility of cancelling the event entirely was raised. In the end, the clouds parted, and after several notable drivers had spun off the slippery track Spanish driver Fernando Alonso emerged victorious.

Some, inevitably, questioned the wisdom of hosting the Korean Grand Prix in this out-of-the-way corner of the country – the simple truth was that Jeonnam province had made the most generous offer to the F1 powers. Despite these inauspicious beginnings, F1 is likely here to stay, and the lessons learned by local authorities will eventually make Mokpo one of the more comfortable stops on the motor racing calendar.

Accommodation

Despite the city’s newfound wealth, there are few options at the top end of the accommodation range. Numerous places are springing up in Hadang (

), however, a modern new zone on reclaimed land east of the centre that may become the best place to stay. Further down the price scale, there are dozens of fairly decent motels around the bus terminal, and an older collection of yeogwan by the train station. Fans of jjimjilbangs could head for the brand-new one five minutes’ walk north of the bus terminal, on the same main road.

), however, a modern new zone on reclaimed land east of the centre that may become the best place to stay. Further down the price scale, there are dozens of fairly decent motels around the bus terminal, and an older collection of yeogwan by the train station. Fans of jjimjilbangs could head for the brand-new one five minutes’ walk north of the bus terminal, on the same main road.

Baekje Hotel  Sangnakdong

Sangnakdong  061/245-0080. The only official hotel in the train station area, though in reality it’s just a motel with a couple of twin rooms. Prices are reasonable, however, and it’s less seedy than neighbouring motels.

061/245-0080. The only official hotel in the train station area, though in reality it’s just a motel with a couple of twin rooms. Prices are reasonable, however, and it’s less seedy than neighbouring motels.

Daemyeongjang Yeogwan  Opposite train station

Opposite train station  061/244-2576. This yeogwan is usually the cheapest around the train station, often offering discounts for single travellers. The rooms are fine (and cockroach-free, unlike some neighbouring yeogwan), and many have a TV, a/c and private bathroom.

061/244-2576. This yeogwan is usually the cheapest around the train station, often offering discounts for single travellers. The rooms are fine (and cockroach-free, unlike some neighbouring yeogwan), and many have a TV, a/c and private bathroom.

Daeyang Park Motel

Daeyang Park Motel  Chukbokdong

Chukbokdong  061/243-4540. One of the better options in this area, its stairwells and some corridors lit up with ultraviolet lights, stars and planets. After this NASA-friendly introduction the rooms are almost disappointingly plain – clean, with big TVs, internet-ready computers and free toiletries.

061/243-4540. One of the better options in this area, its stairwells and some corridors lit up with ultraviolet lights, stars and planets. After this NASA-friendly introduction the rooms are almost disappointingly plain – clean, with big TVs, internet-ready computers and free toiletries.

Shangria Beach Hotel Hadang  061/285-0100. Large hotel by the water in the new Hadang district, a taxi ride east of central Mokpo. Rooms are large and well kitted out, and though the prices can be a little high (off-season discounts notwithstanding) it’s Mokpo’s only decent option in this price range.

061/285-0100. Large hotel by the water in the new Hadang district, a taxi ride east of central Mokpo. Rooms are large and well kitted out, and though the prices can be a little high (off-season discounts notwithstanding) it’s Mokpo’s only decent option in this price range.

Shinan Beach Hotel Seongsandong  061/243-3399. Cut off from the city centre by the mountains and with views of the sea, this was for decades Mokpo’s only tourist hotel. Nowadays its stylings feel more than a little dated, and continued neglect may well kill it off before long.

061/243-3399. Cut off from the city centre by the mountains and with views of the sea, this was for decades Mokpo’s only tourist hotel. Nowadays its stylings feel more than a little dated, and continued neglect may well kill it off before long.

Yudalsan and around

Mokpo is a city of dubious charms that the short-term visitor may be unable to appreciate. Its main draw lies outside the city with the mind-boggling number of islands accessible by ferry. Many of these are visible from the peaks of Yudalsan ( ; daily 8am–6pm; W700), a small hill-park within walking distance of the city centre and train station. It’s a popular place, with troupes of hikers stomping their way up a maze of trails, past manicured gardens and a sculpture park, towards Ildeung-bawi, the park’s main peak. After the slog to the top – a twenty-minute climb of 228m – you’ll be rewarded with a spectacular view: a sea filled to the horizon with a swarm of emerald islands, some large enough to be inhabited, others just specks of rock. Similar views can be had from Yudalsan’s second-highest peak, Ideung-bawi, just along the ridge past a large, precariously balanced boulder.

; daily 8am–6pm; W700), a small hill-park within walking distance of the city centre and train station. It’s a popular place, with troupes of hikers stomping their way up a maze of trails, past manicured gardens and a sculpture park, towards Ildeung-bawi, the park’s main peak. After the slog to the top – a twenty-minute climb of 228m – you’ll be rewarded with a spectacular view: a sea filled to the horizon with a swarm of emerald islands, some large enough to be inhabited, others just specks of rock. Similar views can be had from Yudalsan’s second-highest peak, Ideung-bawi, just along the ridge past a large, precariously balanced boulder.

Between the peaks, a trail runs west to a small beach. The water is not suitable for swimming, but hour-long ferry cruises run regularly to nearby islands from outside the nearby Shinan Beach Hotel. These tours offer delightful views of the islands that surround Mokpo, but bear in mind that the regular ferry routes from the city’s main terminal are cheaper, longer, and offer a greater opportunity to observe island life.

The museum district

A handful of museums lie to the east of the centre, accessible on bus #111, but better approached by taxi. The most popular of this modern collective is the Maritime Museum ( ; Tues–Fri 9am–6pm, Sat & Sun 9am–7pm; W600), whose prime exhibits are the remains of a ship sunk near Wando in the eleventh century – the oldest such find in the country. Preserved from looting by its sunken location, celadon bowls and other relics scavenged from the vessel are on display, alongside a mock-up of how the ship may have once looked. Across the road is the large, breezy and modern Pottery Museum (

; Tues–Fri 9am–6pm, Sat & Sun 9am–7pm; W600), whose prime exhibits are the remains of a ship sunk near Wando in the eleventh century – the oldest such find in the country. Preserved from looting by its sunken location, celadon bowls and other relics scavenged from the vessel are on display, alongside a mock-up of how the ship may have once looked. Across the road is the large, breezy and modern Pottery Museum ( ; same times; free), which contains almost nothing of interest. Along the road, and marginally more compelling, is the Natural History Museum (

; same times; free), which contains almost nothing of interest. Along the road, and marginally more compelling, is the Natural History Museum ( ; same times; W3000), home to an artily arranged butterfly exhibit, as well as a collection of dinosaur skeletons that is sure to perk up any sleepy youngster. Accessible on the same ticket, the building next door contains rather more highbrow sights, including calligraphy and paintings from Sochi, a famed nineteenth-century artist from the local area. Sochi was a protégé of Chusa, one of the country’s most revered calligraphers. More works from this talented duo and their contemporaries are on display, as are modern works by Oh Sung-oo, a Korean impressionist who painted modern takes of oriental clichés.

; same times; W3000), home to an artily arranged butterfly exhibit, as well as a collection of dinosaur skeletons that is sure to perk up any sleepy youngster. Accessible on the same ticket, the building next door contains rather more highbrow sights, including calligraphy and paintings from Sochi, a famed nineteenth-century artist from the local area. Sochi was a protégé of Chusa, one of the country’s most revered calligraphers. More works from this talented duo and their contemporaries are on display, as are modern works by Oh Sung-oo, a Korean impressionist who painted modern takes of oriental clichés.

Eating, drinking and nightlife

You can’t walk for five minutes in downtown Mokpo without passing a dozen restaurants serving cheap, delicious food. The area west of the train station is packed with all kinds of options, from cheap-as-chips snack bars to swanky galbi dens – note, though that the museum area has next to no places to eat. For a caffeine fix or a green tea latte, there are stacks of cafés both in Hadang and the train station area; the best in the latter is Café Manon on the access road to Yudalsan, a friendly escape filled with old turntables, gramophones and the like.

Hadang is the best place to head for a night out. On one particularly alcohol-fuelled street, Wa Bar and the New York Bar fight it out for the expat dollar, with the latter putting on a dance party every last Friday of the month. Alternatively, ask at one of the many convenience stores for a bottle of Mokpo makkeolli, a delicious local version of the drink.

Restaurants

Unless otherwise stated, the establishments listed here are in and around Mokpo’s main shopping quarter, which lies between Yudalsan and the train station.

Chungmu Gimbap  Downtown. This small chain serves up cheap but passable versions of the dish it’s named after – spicy octopus with gimchi and laver-rolled rice, a speciality of Tongyeong in Gyeongsang province – plus the regular chain dishes.

Downtown. This small chain serves up cheap but passable versions of the dish it’s named after – spicy octopus with gimchi and laver-rolled rice, a speciality of Tongyeong in Gyeongsang province – plus the regular chain dishes.

Laura Cheuk-hudong. Just down the road from Café Manon, this well-designed restaurant serves Korean versions of Western dishes at reasonable prices, including delicious smoked chicken.

Namupo

Namupo  Downtown. Head here for the juiciest galbi in town, right in the city centre to boot. There’s a variety of meat styles on the illustrated, English-language menu, though the dish of choice is the aromatic Namupo galbi.

Downtown. Head here for the juiciest galbi in town, right in the city centre to boot. There’s a variety of meat styles on the illustrated, English-language menu, though the dish of choice is the aromatic Namupo galbi.

Napoli Jukgyudong. Steaks and seafood fried rice are among the dishes on offer at this two-storey restaurant on the waterfront near Yudal Beach, on the western side of Yudalsan. Sadly, the pretty sea views aren’t always matched by the dishes.

Raw Fish Town The main road opposite the ferry terminal is alive with raw fish outlets. English-language menus are nonexistent, but a simple solution is at hand – the fish are still alive outside each restaurant in glass tanks, so just point at what you want and agree a price. Alternatively, go for a mixed sashimi platter ( ; modeum-hoe), which will work out at about W20,000 per head.

; modeum-hoe), which will work out at about W20,000 per head.

Looking west from Mokpo’s Yudalsan peaks, you’ll find a sea filled to the horizon with an assortment of islands – there are up to three thousand off Jeolla, and though many of these are merely bumps of rock that yo-yo in and out of the surf with the tide, hundreds are large enough to support fishing communities. The quantity is so vast, indeed, that it’s easier to trailblaze here than in some less-developed Asian countries – many of the islands’ inhabitants have never seen a foreigner, and it’s hard to find a more quintessentially Korean experience.

Much of the area is under the umbrella of Dadohae Haesang National Park, which stretches offshore from Mokpo to Yeosu. The two most popular islands in the park are Hongdo, which rises steeply from the West Sea, and neighbouring Heuksando, a miniature archipelago of more than a hundred islets of rock. Further down the coast are Jindo, which owes its popularity to the local tide’s annual parting of the sea, and Wando, connected to the mainland by road, but surrounded by an island constellation of its own.

All of the following islands are accessible from the ferry terminal in central Mokpo; service at the tourist information office here is hit-and-miss, but at the very least you’ll be able to pick up a map of the islands (the one named “Shinan Travel” was best at the time of writing) and an up-to-date ferry schedule.

Around Mokpo

The key to enjoying the islands around Mokpo is to kick back like the locals and do your own thing – just pick up a map, select an island at random, and make your way there; if you stop somewhere nice along the way, stay there instead. The islanders are among the friendliest people in Korea – some travellers have found themselves stuck on an island with no restaurants or accommodation, only to be taken in by a local family. These islands are not cut out for tourism and possess very few facilities, particularly in terms of banking – so be sure to take along enough money for your stay. It’s also a good idea to bring a bike and/or hiking boots, as the natural surroundings mean that you’re bound to be spending a lot of time outdoors.

One of the most pleasing ferry circuits connects come of Mokpo’s closest island neighbours – a round-trip will take around two hours, and there are several ferries per day. The only island that sees any tourists whatsoever is Oedaldo ( ), which has a decent range of accommodation and restaurants. Only a few kilometres from the mainland, though hidden by other islands, little Dallido (

), which has a decent range of accommodation and restaurants. Only a few kilometres from the mainland, though hidden by other islands, little Dallido ( ; home to just 104 families) offers some of the best walking opportunities. Beyond these lie a pack of much larger islands, accessible on several ferry routes from Mokpo (Korean-only maps are available at the ferry terminal). Most of these will have beaches and hills to climb.

; home to just 104 families) offers some of the best walking opportunities. Beyond these lie a pack of much larger islands, accessible on several ferry routes from Mokpo (Korean-only maps are available at the ferry terminal). Most of these will have beaches and hills to climb.

Hongdo and Heuksando

Lying on their own, well clear of the emerald constellations that surround Mokpo, and more than 100km west of the mainland, are this oddly matched pair of islands. Furthest-flung is Hongdo ( ), whose slightly peculiar rock colouration gave rise to its name, which means “Red Island”. Those who make it this far are less likely to be interested in its pigment than its spectacular shape. Spanning around 6km from north to south, the island rises sheer from the waters of the West Sea to almost 380m above sea level, with valleys slicing through the deep expanses of dense forest as though pared by a gigantic knife. It may seem like a hikers’ paradise, but much of the island is protected, which means that most views of the rock formations will have to be from a boat. Tours (2hr 30min; W15,000) run from the tiny village where the ferry docks, one of only two on an island whose population barely exceeds five hundred; most trips go around the rocky spires of Goyerido (

), whose slightly peculiar rock colouration gave rise to its name, which means “Red Island”. Those who make it this far are less likely to be interested in its pigment than its spectacular shape. Spanning around 6km from north to south, the island rises sheer from the waters of the West Sea to almost 380m above sea level, with valleys slicing through the deep expanses of dense forest as though pared by a gigantic knife. It may seem like a hikers’ paradise, but much of the island is protected, which means that most views of the rock formations will have to be from a boat. Tours (2hr 30min; W15,000) run from the tiny village where the ferry docks, one of only two on an island whose population barely exceeds five hundred; most trips go around the rocky spires of Goyerido ( ), a beautiful formation poking out of the sea just north of Hongdo.

), a beautiful formation poking out of the sea just north of Hongdo.

In contrast to Hongdo’s chunk of steep terrain, Heuksando ( ) is a jagged collection of isles that’s fully open for hiking. There are some great trails, with the most westerly ones highly recommended at sunset, when Hongdo is thrown into silhouette on the West Sea; most people head to the 227m-high peak of Sangnabong. Ferries usually dock at Yeri, Heuksando’s main village, from where boat tours (2hr 30min; W15,000) of the dramatic coast are available, though some choose to hire a taxi (W60,000 for around 3hr) to see the island’s interior.

) is a jagged collection of isles that’s fully open for hiking. There are some great trails, with the most westerly ones highly recommended at sunset, when Hongdo is thrown into silhouette on the West Sea; most people head to the 227m-high peak of Sangnabong. Ferries usually dock at Yeri, Heuksando’s main village, from where boat tours (2hr 30min; W15,000) of the dramatic coast are available, though some choose to hire a taxi (W60,000 for around 3hr) to see the island’s interior.

Practicalities

Both islands are accessed by ferry from the terminal in Mokpo, almost always on the same services; four daily services head to Heuksando (1hr 45min; W31,300), with two of these continuing on to Hongdo (2hr 15min; W38,300). Extra services are laid on in the height of summer, when thousands of tourists descend on the islands, and ferries are packed to the gills: it’s advisable to book tickets in advance through a tourist information office (even those in Seoul will be able to help). Both islands have collections of yeogwan ( ), and if you’re coming during the summer holidays, you are advised to book your accommodation prior to arrival through the tourist offices in Mokpo or Gwangju.

), and if you’re coming during the summer holidays, you are advised to book your accommodation prior to arrival through the tourist offices in Mokpo or Gwangju.

Gwangju and around

The gleaming, busy face of “new Jeolla”, GWANGJU ( ) is the region’s most populous city by far. Once a centre of political activism, and arguably remaining so today, it’s still associated, for most Koreans, with the brutal massacre that took place here in 1980. The event devastated the city but highlighted the faults of the then-government, thereby ushering in a more democratic era. Other than a cemetery for those who perished in the struggle, on the city outskirts, there’s little of note to see in Gwangju itself, except perhaps the shop-and-dine area in its centre. Largely pedestrianized, this is one of the busiest and best such zones in the country – not only the best place in which to sample Jeollanese cuisine but also a great spot to observe why Gwangjuites are deemed to be among the most fashionable folk on the peninsula. Also in this area is “Art Street”, a warren of studios and the figurehead of Gwangju’s dynamic art scene. Although most funding is now thrown at contemporary projects, the city’s rich artistic legacy stems in part from the work of Uijae, one of the country’s most famed twentieth-century painters and a worthy poet to boot. A museum dedicated to the great man sits on his former patch – a building and tea plantation on the slopes of Mudeungsan Park, which forms a natural eastern border to the city.

) is the region’s most populous city by far. Once a centre of political activism, and arguably remaining so today, it’s still associated, for most Koreans, with the brutal massacre that took place here in 1980. The event devastated the city but highlighted the faults of the then-government, thereby ushering in a more democratic era. Other than a cemetery for those who perished in the struggle, on the city outskirts, there’s little of note to see in Gwangju itself, except perhaps the shop-and-dine area in its centre. Largely pedestrianized, this is one of the busiest and best such zones in the country – not only the best place in which to sample Jeollanese cuisine but also a great spot to observe why Gwangjuites are deemed to be among the most fashionable folk on the peninsula. Also in this area is “Art Street”, a warren of studios and the figurehead of Gwangju’s dynamic art scene. Although most funding is now thrown at contemporary projects, the city’s rich artistic legacy stems in part from the work of Uijae, one of the country’s most famed twentieth-century painters and a worthy poet to boot. A museum dedicated to the great man sits on his former patch – a building and tea plantation on the slopes of Mudeungsan Park, which forms a natural eastern border to the city.

“At 10.30 in the morning about a thousand Special Forces troops were brought in. They repeated the same actions as the day before, beating, stabbing and mutilating unarmed civilians, including children, young girls and aged grandmothers... Several sources tell of soldiers stabbing or cutting off the breasts of naked girls; one murdered student was found disembowelled, another with an X carved in his back... And so it continues, horror piled upon horror.”

Simon Winchester, Korea

Away from the bustle of Gwangju, in what may at first appear to be a field of contorted tea trees, lie those who took part in a 1980 uprising against the government, an event which resulted in a brutal massacre of civilians. The number that died is still not known for sure, and was exaggerated by both parties involved at the time; the official line says just over two hundred, but some estimates put it at over two thousand. Comparisons with the Tiananmen massacre in China are inevitable, an event better known to the Western world despite what some historians argue may have been a similar death toll. While Beijing keeps a tight lid on its nasty secret, Koreans flock to Gwangju each May to pay tribute to those who died.

In an intricate web of corruption, apparent Communist plots and a presidential assassination, trouble had been brewing for some time before General Chun Doo-hwan staged a military coup in December 1979. Chun had been part of a team given the responsibility of investigating the assassination of President Kim Jae-kyu, but used the event as a springboard towards his own leadership of the country. On May 17, 1980, he declared martial law in order to quash student protests against his rule. Similar revolts had seen the back of a few previous Korean leaders (notably Syngman Rhee, the country’s first president); fearing the same fate, Chun authorized a ruthless show of force that left many dead. Reprisal demonstrations started up across the city; the MBC television station was burnt down, with protestors aggrieved at being portrayed as Communist hooligans by the state-run operator. Hundreds of thousands of civilians grouped together, mimicking the tactics of previous protests on Jeju Island by attacking and seizing weapons from police stations. With transport connections to the city blocked, the government were able to retreat and pool their resources for the inevitable crackdown. This came on May 27, when troops attacked by land and air, retaking the city in less than two hours. After having the protest leaders executed, General Chun resigned from the Army in August, stepping shortly afterwards into presidential office. His leadership, though further tainted by continued erosions of civil rights, oversaw an economic boom; an export-hungry world remained relatively quiet on the matter.

Also sentenced to death, though eventually spared, was Kim Dae-jung. An opposition leader and fierce critic of the goings-on, he was charged with inciting the revolt, and spent much of the decade under house arrest. Chun, after seeing out his term in 1987, passed the country’s leadership to his partner-in-crime during the massacre, Roh Tae-woo. Demonstrations soon whipped up once more, though in an unexpectedly conciliatory response, Roh chose to release many political prisoners, including Kim Dae-jung. The murky world of Korean politics gradually became more transparent, culminating in charges of corruption and treason being levelled at Chun and Roh. Both were pardoned in 1997 by Kim Dae-jung, about to be elected president himself, in what was generally regarded as a gesture intended to draw a line under the troubles.

Arrival

Despite the substantial funds thrown at it by the city government, Gwangju’s public transport network is poor for a Korean city. A brand-new subway line runs through the centre from east to west, but for some reason doesn’t connect with the train station or bus terminal (both of which are fairly central); this is particularly odd considering that the latter, a mall-style structure that serves both express and intercity buses, is also new. Getting from the bus terminal to other points in the city is tough – the area is full of traffic, and the bus stops on the busy main road outside are blocked by cars and taxis waiting for passengers. Those who wish to take a local bus often have to run out into the traffic – that’s if they manage to see their bus coming. Add to that a confusing series of bus numbers and you have a recipe for chaos. Alighting from the train station is far simpler and more convenient.

The airport, just over 6km west of the centre, is served by a couple of short-haul international services; this actually is a stop on the subway line, while a taxi to the centre should cost less than W10,000.

Orientation and information