Jeju Island

Highlights

Udo by bike There are few more enjoyable activities in all Korea than gunning around this tiny island’s narrow lanes on a scooter.

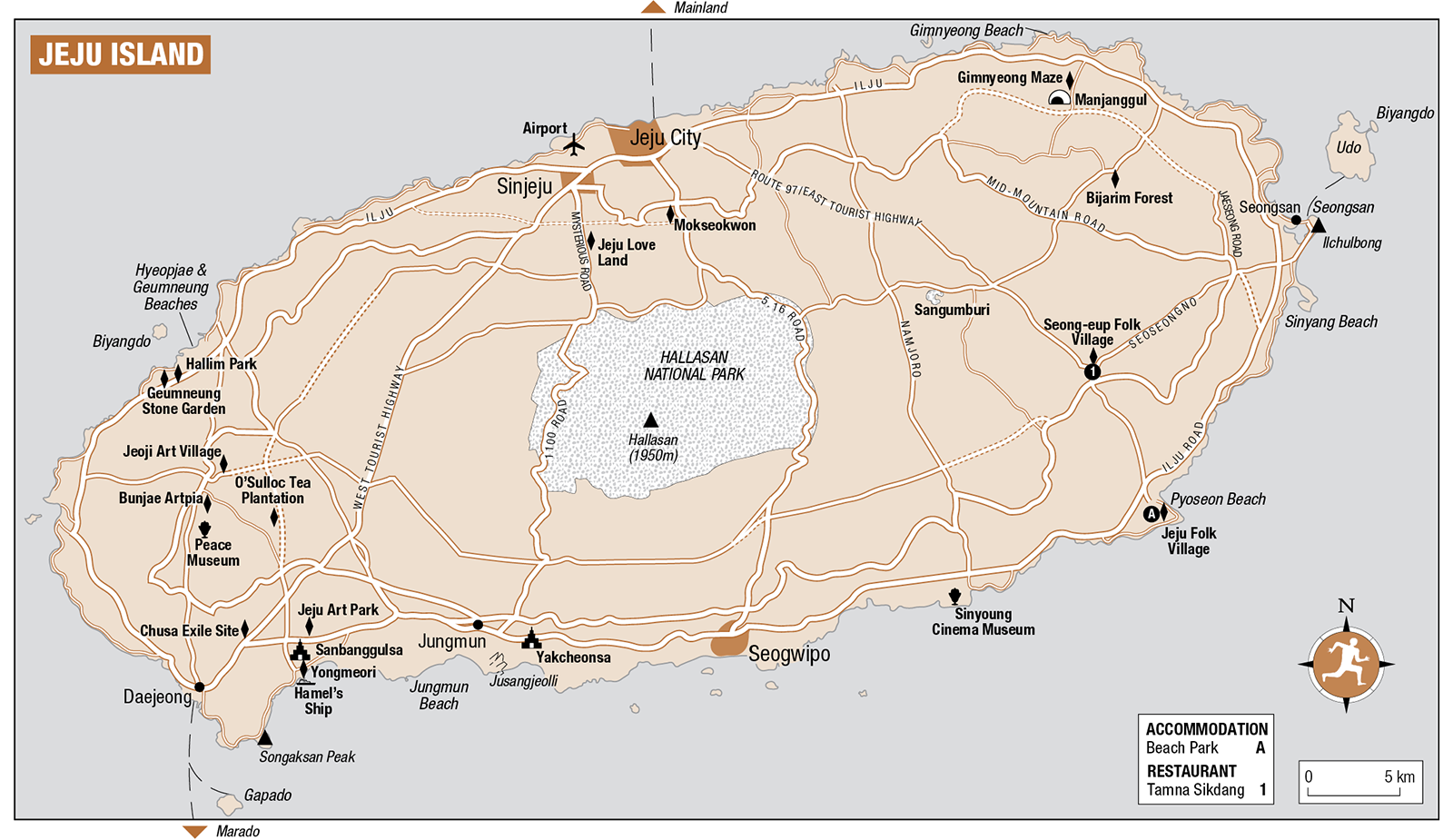

Route 97 A rural day-trip along this road can see you take in a volcanic crater, a folk village and a culture museum, before finishing at the beach.

Seogwipo Flanked by waterfalls, Jeju’s second largest city is a relaxed base for tours of the sunny southern coast.

Teddy Bear Museum The moon landings and the fall of the Berlin Wall are just some of the events to be given teddy treatment at this shrine to high kitsch.

Yakcheonsa Turn up for the evening service at this remote temple for one of Jeju’s most magical experiences.

Geumneung Stone Garden See whole legions of hareubang – distinctive rock statues, and the number one symbol of Jeju.

Hallasan Korea’s highest point at 1950m, this mountain dominates the island and just begs to be climbed.

The mass of islands draping off Korea’s southern coast fades into the Pacific, before coming to an enigmatic conclusion in the crater-pocked JEJU ISLAND, known locally as Jejudo ( ). This tectonic pimple in the South Sea is the country’s number-one holiday destination, particularly for Korean honeymooners, and it’s easy to see why – the volcanic crags, innumerable beaches and colourful rural life draw comparisons with Hawaii and Bali, a fact not lost on the local tourist authorities. This very hype puts many foreign travellers off, but while the five-star hotels and tour buses can detract from Jeju’s natural appeal, the island makes for a superb visit if taken on its own terms; indeed those who travel into Jeju’s more remote areas may come away with the impression that little has changed here for decades. In many ways it’s as if regular Korea has been given a makeover – splashes of tropical green fringe fields topped off with palm trees and tangerine groves, and while Jeju’s weather may be breezier and damper than the mainland, its winter is eaten into by lengthier springs and autumns, allowing oranges, pineapples and dragon fruit to grow.

). This tectonic pimple in the South Sea is the country’s number-one holiday destination, particularly for Korean honeymooners, and it’s easy to see why – the volcanic crags, innumerable beaches and colourful rural life draw comparisons with Hawaii and Bali, a fact not lost on the local tourist authorities. This very hype puts many foreign travellers off, but while the five-star hotels and tour buses can detract from Jeju’s natural appeal, the island makes for a superb visit if taken on its own terms; indeed those who travel into Jeju’s more remote areas may come away with the impression that little has changed here for decades. In many ways it’s as if regular Korea has been given a makeover – splashes of tropical green fringe fields topped off with palm trees and tangerine groves, and while Jeju’s weather may be breezier and damper than the mainland, its winter is eaten into by lengthier springs and autumns, allowing oranges, pineapples and dragon fruit to grow.

Around the island, you’ll see evidence of a rich local culture quite distinct from the mainland, most notably in the form of the hareubang – these cute, grandfatherly statues of volcanic rock were made for reasons as yet unexplained, and pop up all over the island. Similarly ubiquitous are the batdam, walls of hand-stacked volcanic rock that separate the farmers’ fields: like the drystone walls found across Britain, these were built without any bonding agents, the resulting gaps letting through the strong winds that often whip the island. Jeju’s distinctive thatch-roofed houses are also abundant, and the island even has a breed of miniature horse; these are of particular interest to Koreans due to the near-total dearth of equine activity on the mainland. Also unique to Jeju are the haenyeo, female divers who plunge without breathing apparatus into often treacherous waters in search of shellfish and sea urchins. Although once a hard-as-nails embodiment of the island’s matriarchal culture, their dwindling numbers mean that this occupation is in danger of petering out.

Jeju City is the largest settlement, and whether you arrive by plane or ferry, this will be your entry point. You’ll find the greatest choice of accommodation and restaurants here, and most visitors choose to hole up in the city for the duration of their stay, as the rest of the island is within day-trip territory. Although there are a few sights in the city itself, getting out of town is essential if you’re to make the most of your trip. On the east coast is Seongsan, a sumptuously rural hideaway crowned by Ilchulbong, a green caldera that translates as “Sunrise Peak”; ferries run from here to Udo, a tiny islet that somehow manages to be yet even more bucolic. Inland are the Manjanggul lava tubes, one of the longest such systems in the world, and Sangumburi, the largest and most accessible of Jeju’s many craters. All roads eventually lead to Seogwipo on the south coast; this relaxed, waterfall-flanked city is Jeju’s second-largest settlement, and sits next to the five-star resort of Jungmun. Sights in Jeju’s west are a little harder to access, but this makes a trip all the more worthwhile – the countryside you’ll have to plough through is some of the best on the island, with the fields yellow with rapeseed in spring, and carpeted from summer to autumn with the pink-white-purple tricolour of cosmos flowers. Those with an interest in calligraphy may want to seek out the remote former home of Chusa, one of the country’s most famed exponents of the art. In the centre of the island is Hallasan, an extinct volcano and the country’s highest point at 1950m, visible from much of the island, though often obscured by Jeju’s fickle weather.

Jeju is one of the few places in Korea where renting a car or bike makes sense. Outside Jeju City, roads are generally empty and the scenery is almost always stunning, particularly in the inland areas, where you’ll find tiny communities, some of which will never have seen a foreigner. Bicycle trips around the perimeter of the island are becoming ever more popular, with riders usually taking four days to complete the circuit – Seongsan, Seogwipo and Daecheong make logical overnight stops.

Jejudo burst into being around two million years ago in a series of volcanic eruptions, but prior to an annexation by the mainland Goryeo dynasty in 1105 its history is sketchy and unknown. While the mainland was being ruled by the famed Three Kingdoms of Silla, Baekje and Goguryeo, Jeju was governed by the mysterious Tamna kingdom, though with no historical record of Tamna’s founding, it is left to Jeju myth to fill in the gaps: according to legend, the three founders of the country – Go, Bu and Yang – rose from the ground at a spot now marked by Samseonghyeol shrine in Jeju City. On a hunting trip shortly after this curious birth, they found three maidens who had washed up on a nearby shore armed with grain and a few animals; the three fellows married the girls and using the material and livestock set up agricultural communities, each man kicking off his own clan. Descendants of these three families conduct twice-yearly – in spring and autumn – ceremonies to worship their ancestors.

More prosaically, the Samguk Sagi – Korea’s main historical account of the Three Kingdoms period – states that Tamna in the fifth century became a tributary state to the Baekje kingdom on the mainland’s southwest, then hurriedly switched allegiance before the rival Silla kingdom swallowed Baekje whole in 660. Silla itself was consumed in 918 by the Goryeo dynasty, which set about reining in the island province; Jeju gradually relinquished autonomy before a full takeover in 1105. The inevitable Mongol invasion came in the mid-thirteenth century, with the marauding Khaans controlling the island for almost a hundred years. The horses bred here to support Mongol attacks on Japan fostered a local tradition of horsemanship that continues to this day – Jeju is the only place in Korea with significant equine numbers – while the visitors also left an audible legacy in the Jejanese dialect.

In 1404, with Korea finally free of Mongol control, Jeju was eventually brought under control by an embryonic Joseon dynasty. Its location made it the ideal place for Seoul to exile radicals. Two of the most famed of these were King Gwanghaegun, the victim of a coup in 1623, and Chusa, an esteemed calligrapher whose exile site can be found on the west of the island. It was just after this time that the West got its first reports about Korea, from Hendrick Hamel, a crewman on a Dutch trading ship that crashed off the Jeju coast in 1653.

With Jeju continually held at arm’s length by the central government, a long-standing feeling of resentment against the mainland was a major factor in the Jeju Massacre of 1948. The Japanese occupation having recently ended with Japan’s surrender at the end of World War II, the Korean-American coalition sought now to tear out the country’s Communist roots, which were strong on Jejudo. Jejanese guerrilla forces, provoked by regular brutality, staged a simultaneous attack on the island’s police stations. A retaliation was inevitable, and the rebels and government forces continued to trade blows years after the official end of the Korean War in 1953, by which time this largely ignored conflict had resulted in up to thirty thousand deaths, the vast majority on the rebel side.

Things have since calmed down significantly. Jeju returned to its roots as a rural backwater with little bar fishing and farming to sustain its population, but its popularity with mainland tourists grew and grew after Korea’s took off as an economic power, with the island becoming known for the samda, or three bounties – rock, wind and women. Recently tourist numbers have decreased slightly, with richer and more cosmopolitan Koreans increasingly choosing to spend their holidays abroad, though Jeju still remains the country’s top holiday spot.

Jeju is accessible by plane from most mainland airports (usually around W85,000), as well as a fair few cities across eastern Asia; this has long been the preferred form of arrival for locals, and the resultant closure of ferry routes means that planes are generally the way to go for foreign travellers too.

Ferry schedules have long been in a state of flux, but at the time of writing there were a few daily fast (3hr; W50,000) and slow (5hr; W26,000) ferries to Jeju City from Mokpo, as well as overnight journeys every day bar Sunday from Busan (11hr; from W25,000) and Incheon (14hr; W50,000). A daily high-speed route (1hr 50min; W30,000) started up in 2010, linking Seongsan in east Jeju (p.306) with Jangheung on the mainland.

Whichever way you arrive, it’s usually necessary to bring your passport.

Jeju City

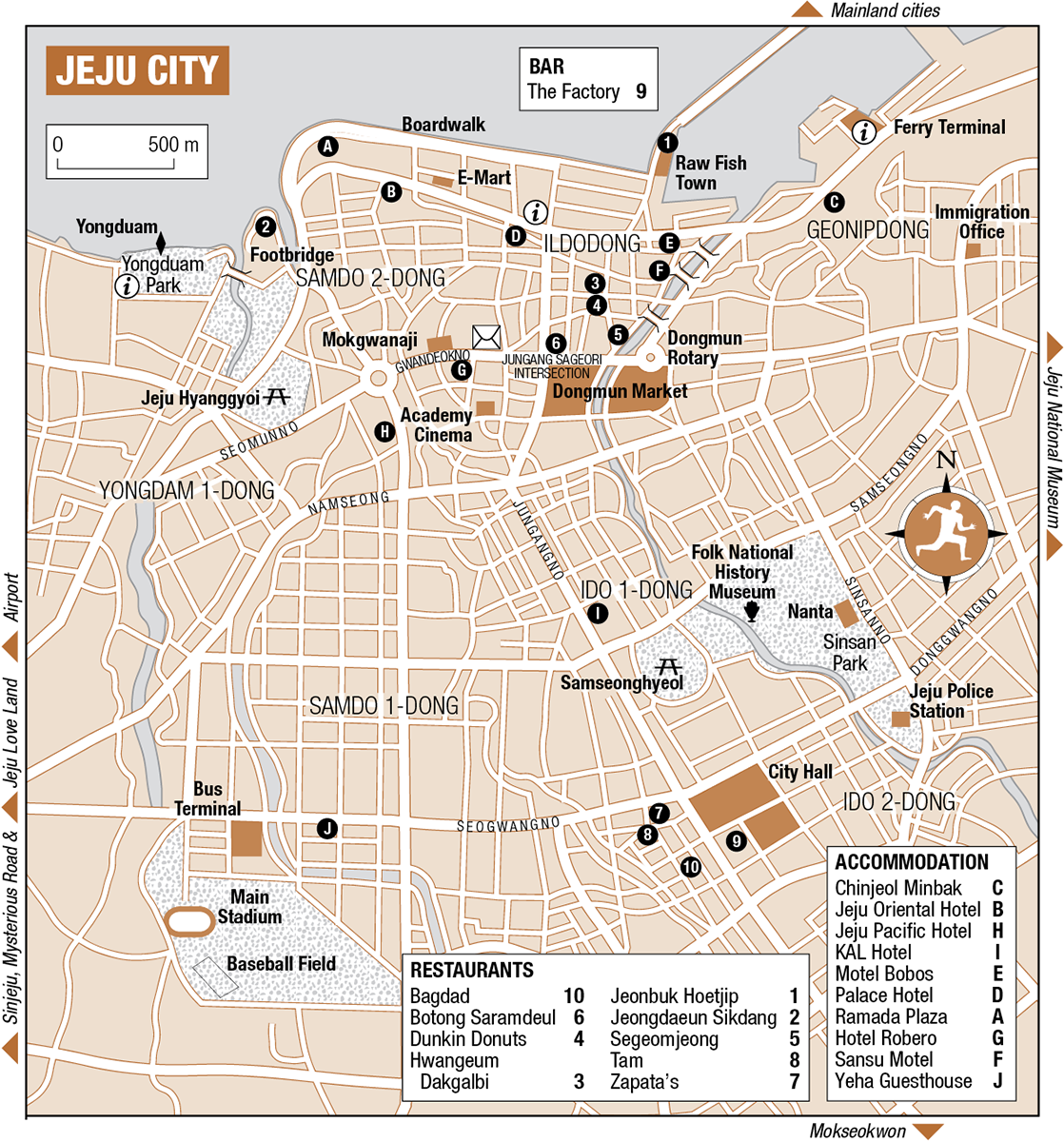

JEJU CITY (jeju-shi;  ) is the provincial capital and home to more than half of its population. Markedly relaxed and low-rise for a Korean city, and loomed over by the extinct volcanic cone of Hallasan, it has a few sights of its own to explore, though palm trees, beaches, tectonic peaks and rocky crags are just a bus-ride away, thus making it a convenient base for the vast majority of the island’s visitors.

) is the provincial capital and home to more than half of its population. Markedly relaxed and low-rise for a Korean city, and loomed over by the extinct volcanic cone of Hallasan, it has a few sights of its own to explore, though palm trees, beaches, tectonic peaks and rocky crags are just a bus-ride away, thus making it a convenient base for the vast majority of the island’s visitors.

Jeju City was, according to local folklore, the place where the island’s progenitors sprung out of the ground (you can still see the holes at Samseonghyeol), and while there are few concrete details of the city’s history up until Joseon times, the traditional buildings of Mokgwanaji, a governmental office located near the present centre of the city, shows that it has long been a seat of regional power. Other interesting sights include Yongduam (“Dragon Head Rock”), a basalt formation rising from the often fierce sea, and Jeju Hyanggyo, a Confucian academy. There are also a couple of vaguely interesting museums, best reserved as shelter on one of Jeju’s many rainy days. South of the centre along the Mysterious Road, where objects appear to roll uphill, is the entertainingly racy Love Land.

Arrival

Domestic flights from several mainland destinations arrive every few minutes, landing at the island’s airport a few kilometres west of the city centre. Six bus routes make the short run to Gujeju, the city centre, the most useful of which is #100 (W850), which heads east every fifteen minutes or so to the bus terminal, then on to Dongmun Rotary in the city centre, or south to Sinjeju. Bus #600 runs at similar intervals to the top hotels in Jungmun (W3900) and Seogwipo (W5000), south of the island. At the eastern edge of the city is the ferry terminal, with connections from several mainland cities. A couple of companies use the International Ferry Terminal, 1km further east on the same road; despite the name there are no regular international connections, though cruise ships occasionally dock here.

Information and city transport

There are, for some reason, two tourist information desks just metres apart from each other at the airport. At least one will be open from 8am to 10pm ( 064/742-8866), but both can supply you with English-language maps and pamphlets and help with anything from renting a car to booking a room. Another booth at the ferry terminal offers similar assistance (10am–8pm;

064/742-8866), but both can supply you with English-language maps and pamphlets and help with anything from renting a car to booking a room. Another booth at the ferry terminal offers similar assistance (10am–8pm;  064/758-7181). English-language help can also be accessed by phone on

064/758-7181). English-language help can also be accessed by phone on  064/1330.

064/1330.

Jeju City is small and relaxed enough to allow for some walking, but in order to see everything you’ll have to resort to taxis – these shouldn’t cost more than W5000 for destinations within Gujeju – or one of the numerous local buses; tickets cost W850 per ride, but unfortunately there are no day-passes. The last services on all routes leave at 9pm or just after, and start again at around 6am.

#12 – West Coastal Road (every 15–25min)

Hallim (40min; W2300)–Sanbangsan (2hr; W5400)–Jungmun (2hr 20min; W6200)–Seogwipo; 2hr 40min; W7300).

#95 – West Tourist Road (every 20min)

Sanbangsan (50min; W3500)–Moseulpo (1hr; W3600).

#95 – Jungmun Express Road (every 10–12min)

Jungmun (1hr; W3300)–Seogwipo (1hr 10min; W3600).

#99 – 1100 road (every 60–90min)

1100m rest area (40min; W2700)–Jungmun (1hr 20min; W5100).

#11 – 5.16 road (every 12–15min)

Seongpanak (35min; W1700)–Seogwipo (1hr 10min; W3600).

Route 97 – East tourist road (every 20–60min)

Sangumburi (25min; W1800)–Seong-eup Folk Village (45min; W2300)–Pyoseon (1hr; W3400)–Jeju Folk Village (1hr 5min; W3600).

Route 12 – East coastal road (every 15–25min)

Gimnyeong (50min; W1900)–Seongsan (1hr 30min; W3800)–Pyoseon (1hr 55min; W5100)–Seogwipo (1hr 40min; W7500).

Accommodation

Jeju’s capital is firmly fixed on Korea’s tourist itinerary; most visitors choose to base themselves here. However, many establishments were built when Korea’s economy was going great guns in the 1980s, and are now beginning to show their age. All higher-end hotels slash their rates by up to fifty percent outside July and August, so be sure to ask about discounts. Often you’ll be asked whether you’d like a “sea view” room facing north, or a “mountain view” facing Hallasan; the latter is usually a little cheaper. There are many cheap motels around the nightlife zone near City Hall, and in the rustic canalside area between Dongmun market and the ferry terminal.

Chinjeol Minbak  Geonipdong

Geonipdong  064/755-5132. One of the cheapest places to stay in the city, with friendly owners who usually try to lure foreign travellers emerging from the ferry terminal, just a short walk away. The atmosphere is pleasant and can feel like a youth hostel at times; try to get a room with a private toilet and TV.

064/755-5132. One of the cheapest places to stay in the city, with friendly owners who usually try to lure foreign travellers emerging from the ferry terminal, just a short walk away. The atmosphere is pleasant and can feel like a youth hostel at times; try to get a room with a private toilet and TV.

Jeju Oriental Hotel Samdodong  064/752-8222,

064/752-8222,  www.oriental.co.kr. Upper rooms have great sea views; few live up to the promise of the large reception area, but you’ll be paying for the facilities anyway – a casino and four restaurants, internet in every room, and courteous staff. Serious competition from the new Ramada Plaza across the road means that discounts of fifty percent are not uncommon.

www.oriental.co.kr. Upper rooms have great sea views; few live up to the promise of the large reception area, but you’ll be paying for the facilities anyway – a casino and four restaurants, internet in every room, and courteous staff. Serious competition from the new Ramada Plaza across the road means that discounts of fifty percent are not uncommon.

Jeju Pacific Hotel Yongdamdong  064/758-2500. Set a bit away from things, though just a 10min walk from the sea, this hotel caters mainly to Japanese visitors, and is accordingly surrounded by sushi restaurants and karaoke rooms. All rooms have internet, and some offer views of Hallasan and the ocean from the same window. Rates are slashed off-season.

064/758-2500. Set a bit away from things, though just a 10min walk from the sea, this hotel caters mainly to Japanese visitors, and is accordingly surrounded by sushi restaurants and karaoke rooms. All rooms have internet, and some offer views of Hallasan and the ocean from the same window. Rates are slashed off-season.

KAL Hotel Idodong  064/724-2001,

064/724-2001,  www.kalhotel.co.kr. An immaculate hotel and Jeju’s tallest building, with 21 floors; friendly, white-suited staff buzz about the place, though the rooms lack character and are small for the price. There’s a funky cocktail bar on the top floor, though budget cuts mean that, sadly, it no longer revolves.

www.kalhotel.co.kr. An immaculate hotel and Jeju’s tallest building, with 21 floors; friendly, white-suited staff buzz about the place, though the rooms lack character and are small for the price. There’s a funky cocktail bar on the top floor, though budget cuts mean that, sadly, it no longer revolves.

Motel Bobos Ildodong  064/727-7200. Don’t be put off by the rather dingy reception area – the wood-floored rooms here are large and airy, and you’ll get a free coffee in the morning. The motel is also within walking distance of the ferry terminal and seaside promenade, as well as some of the city sights.

064/727-7200. Don’t be put off by the rather dingy reception area – the wood-floored rooms here are large and airy, and you’ll get a free coffee in the morning. The motel is also within walking distance of the ferry terminal and seaside promenade, as well as some of the city sights.

Palace Hotel Samdodong  064/753-8811. One of several similar hotels on the waterfront, all of which are showing their age and provide rather austere rooms bettered by many motels. The on-site cocktail bar, sauna and two restaurants put it above the competition nearby.

064/753-8811. One of several similar hotels on the waterfront, all of which are showing their age and provide rather austere rooms bettered by many motels. The on-site cocktail bar, sauna and two restaurants put it above the competition nearby.

Ramada Plaza Samdodong  064/729-8100,

064/729-8100,  www.ramadajeju.co.kr. A modern, cavernous hotel – it’s even bigger than it appears from outside. Vertigo-inducing interior views, plush interiors and some of Jeju’s best food make it the hotel of choice for those who can afford it, though the atmosphere may be a little mall-like, especially when it hosts conventions.

www.ramadajeju.co.kr. A modern, cavernous hotel – it’s even bigger than it appears from outside. Vertigo-inducing interior views, plush interiors and some of Jeju’s best food make it the hotel of choice for those who can afford it, though the atmosphere may be a little mall-like, especially when it hosts conventions.

Hotel Robero Samdodong  064/757-7111,

064/757-7111,  www.roberohotel.com. The modern art strewn about the place fails to disguise the fact that a renovation is overdue, though the rooms themselves are cosy and as good as you’d expect at this price level. Criminally, few have decent views of pretty Mokgwanaji across the road.

www.roberohotel.com. The modern art strewn about the place fails to disguise the fact that a renovation is overdue, though the rooms themselves are cosy and as good as you’d expect at this price level. Criminally, few have decent views of pretty Mokgwanaji across the road.

Sansu Motel

Sansu Motel  Geonipdong

Geonipdong  064/757-1614. Clean rooms with cable TV and decent private facilities come at rock-bottom prices at this guesthouse run by a Korean-Mexican couple. Try to nab a room facing the stream; it’s possible to swim here in summer.

064/757-1614. Clean rooms with cable TV and decent private facilities come at rock-bottom prices at this guesthouse run by a Korean-Mexican couple. Try to nab a room facing the stream; it’s possible to swim here in summer.

Yeha Guesthouse Samdodong  064/724-5506,

064/724-5506,  www.yehaguesthouse.com. Finally, Jeju has a hostel! This friendly, immaculately clean place is a short walk from the bus terminal – an uninteresting part of town, but close to the best bars. Dorms W19,000, doubles

www.yehaguesthouse.com. Finally, Jeju has a hostel! This friendly, immaculately clean place is a short walk from the bus terminal – an uninteresting part of town, but close to the best bars. Dorms W19,000, doubles

The City

The capital’s sights aren’t a patch on those found elsewhere on the island, but some are still worthy of a visit. Most famous are the “Dragon Head Rock” of Yongduam and the shrine at Samseonghyeol; Korean tourists are more or less obliged to pay both a visit and show photographic evidence to friends and family. Between these, in the very centre of town, lies the former seat of Jejanese government known as Mokgwanaji, a relaxing place to take a stroll around genteel oriental buildings. A day should be enough to visit all these places.

Near the seafront

Who’d have thought that basalt could be so romantic. The knobbly seaside formation of Yongduam, or “Dragon Head Rock” ( ; 24hr; free), appears in the honeymoon albums of any Korean couple worth their salt – or, at least, the ones who don’t celebrate their nuptials overseas – and is the defining symbol of the city. From the shore, and in a certain light, the crag does indeed resemble a dragon, though from the higher of two viewing platforms a similar formation to the right appears more deserving of the title. According to Jeju legend, these are the petrified remains of a regal servant who, after scouring Hallasan for magical mushrooms, was turned into a dragon by the offended mountain spirits. Strategically positioned lights illuminate the formation at night, and with fewer people around, this may be the best time to visit. On the way back east towards the city centre, you may be tempted to take one of the gorgeous paths that crisscross into and over tiny, tree-filled Hancheon creek, eventually leading to Jeju Hyanggyo (

; 24hr; free), appears in the honeymoon albums of any Korean couple worth their salt – or, at least, the ones who don’t celebrate their nuptials overseas – and is the defining symbol of the city. From the shore, and in a certain light, the crag does indeed resemble a dragon, though from the higher of two viewing platforms a similar formation to the right appears more deserving of the title. According to Jeju legend, these are the petrified remains of a regal servant who, after scouring Hallasan for magical mushrooms, was turned into a dragon by the offended mountain spirits. Strategically positioned lights illuminate the formation at night, and with fewer people around, this may be the best time to visit. On the way back east towards the city centre, you may be tempted to take one of the gorgeous paths that crisscross into and over tiny, tree-filled Hancheon creek, eventually leading to Jeju Hyanggyo ( ), a Confucian shrine and school built at the dawn of the Joseon dynasty in the late fourteenth century. Though not quite as attractive as other such facilities around the country, this academy is still active, and hosts age-old ancestral rite ceremonies in spring and autumn.

), a Confucian shrine and school built at the dawn of the Joseon dynasty in the late fourteenth century. Though not quite as attractive as other such facilities around the country, this academy is still active, and hosts age-old ancestral rite ceremonies in spring and autumn.

In the centre of the city are the elegant, traditional buildings of Mokgwanaji ( ; daily 8am–7pm; W1500), a recently restored site that was Jeju’s political and administrative centre during the Joseon dynasty; it’s a relaxing place that makes for a satisfying meander. Honghwagak, to the back of the complex, was a military officials’ office established in 1435 during the rule of King Sejong – the creator of hangeul, Korea’s written text, featured on the W10,000 note – and since rebuilt and repaired countless times. The place also provides evidence that vice and nit-picking are far from new to Korean politics – several buildings once housed concubines, entertainment girls, and “female government slaves”, while the pond-side banquet site near the site entrance was repossessed due to “noisy frogs”.

; daily 8am–7pm; W1500), a recently restored site that was Jeju’s political and administrative centre during the Joseon dynasty; it’s a relaxing place that makes for a satisfying meander. Honghwagak, to the back of the complex, was a military officials’ office established in 1435 during the rule of King Sejong – the creator of hangeul, Korea’s written text, featured on the W10,000 note – and since rebuilt and repaired countless times. The place also provides evidence that vice and nit-picking are far from new to Korean politics – several buildings once housed concubines, entertainment girls, and “female government slaves”, while the pond-side banquet site near the site entrance was repossessed due to “noisy frogs”.

There’s an appealing walk along the seafront promenade, a few hundred metres north of Mokgwanaji, which curls around the Ramada Plaza hotel and east to a large bank of seafood restaurants that marks the beginning of the harbour. In bad weather the waves scud in to bash the rocks beneath the boardwalk, producing impressive jets of spray; sea breaks are in place, but you should exercise caution all the same.

Samseonghyeol

Jeju’s spiritual home, Samseonghyeol ( ; daily 8am–6.30pm; W2500), is a shrine that attracts a fair number of Korean tourists year-round. Local legend has it that the island was originally populated by Go, Bu and Yang, three local demigods that rose from the ground here. The glorified divots are visible in a small, grassy enclosure at the centre of the park, though it’s hard to spend more than a few seconds looking at what are, in effect, little more than holes in the ground. The pleasant wooded walking trails that line the complex will occupy more of your time, and there are a few buildings to peek into as well as an authentic hareubang outside the entrance.

; daily 8am–6.30pm; W2500), is a shrine that attracts a fair number of Korean tourists year-round. Local legend has it that the island was originally populated by Go, Bu and Yang, three local demigods that rose from the ground here. The glorified divots are visible in a small, grassy enclosure at the centre of the park, though it’s hard to spend more than a few seconds looking at what are, in effect, little more than holes in the ground. The pleasant wooded walking trails that line the complex will occupy more of your time, and there are a few buildings to peek into as well as an authentic hareubang outside the entrance.

Heading east along Samseongno you’ll come to the Folklore and Natural History Museum ( ; daily 8.30am–6pm; W1100). Local animals in stuffed and skeletal form populate the first rooms, before the diorama overload of the folklore exhibition, where the ceremonies, dwellings and practices of old-time Jeju are brought to plastic life. Unless you’re planning to visit the two folk villages on Route 97, there are few better ways to get a grip on the island’s history.

; daily 8.30am–6pm; W1100). Local animals in stuffed and skeletal form populate the first rooms, before the diorama overload of the folklore exhibition, where the ceremonies, dwellings and practices of old-time Jeju are brought to plastic life. Unless you’re planning to visit the two folk villages on Route 97, there are few better ways to get a grip on the island’s history.

A taxi-ride (W3000) further east is Jeju National Museum ( ; Tues–Fri 9am–6pm, Sat & Sun 9am–7pm; W1000, free 1hr before closing). As with all other “national” museums around the country, it focuses almost exclusively on regional finds, but as this particular institution – despite its size – has surprisingly little to see, the free hour before closing time is enough for many visitors. Highlights include some early painted maps, a collection of celadon pottery dating from the twelfth century, and a small but excellent display of calligraphy – be sure to take a look at the original Sehando, a letter-cum-painting created by Chusa, one of Korea’s most revered calligraphers. The upper floor is not open so you’ll have to make do with staring up at the sprawling stained-glass ceiling from the lobby.

; Tues–Fri 9am–6pm, Sat & Sun 9am–7pm; W1000, free 1hr before closing). As with all other “national” museums around the country, it focuses almost exclusively on regional finds, but as this particular institution – despite its size – has surprisingly little to see, the free hour before closing time is enough for many visitors. Highlights include some early painted maps, a collection of celadon pottery dating from the twelfth century, and a small but excellent display of calligraphy – be sure to take a look at the original Sehando, a letter-cum-painting created by Chusa, one of Korea’s most revered calligraphers. The upper floor is not open so you’ll have to make do with staring up at the sprawling stained-glass ceiling from the lobby.

South of the city

It may seem a little cheeky to have a dedicated rock-and-tree park on an island that’s filled with little else, but Mokseokwon ( ; daily 8am–9pm; winter 8am–8pm; W2000), just a few kilometres south of Jeju City, is a delightful place. Arty exhibits here, made from assorted pieces of stone and wood found around the island, provoke a range of feelings from triumph to contemplation. While none is astonishing individually, a lot of thought has gone into the park as a whole: on one side of the complex, a romantic story is played out in rock form; though cheesy, the contorted shapes of stones in love do their best to fire your imagination. The site is just a little too far south of the city to be overrun with visitors, but is easy to get to; bus #500 (25min) runs from various stops.

; daily 8am–9pm; winter 8am–8pm; W2000), just a few kilometres south of Jeju City, is a delightful place. Arty exhibits here, made from assorted pieces of stone and wood found around the island, provoke a range of feelings from triumph to contemplation. While none is astonishing individually, a lot of thought has gone into the park as a whole: on one side of the complex, a romantic story is played out in rock form; though cheesy, the contorted shapes of stones in love do their best to fire your imagination. The site is just a little too far south of the city to be overrun with visitors, but is easy to get to; bus #500 (25min) runs from various stops.

A few kilometres southwest of Jeju City, and best accessed by taxi, are a couple of intriguing sights. One short section of Route 99, christened the Mysterious Road ( ), has achieved national fame, and though no scheduled buses run to this notorious stretch of tarmac, there’s always plenty of traffic – cars and tour buses, or indeed pencils, cans of beer or anything else capable of rolling down a hill, are said to roll upwards here. Needless to say, it’s a visual illusion created by the angles of the road and the lay of the land. Some people think it looks convincing, while others wonder why people are staring with such wonder at objects rolling down a slight incline, but it makes for a surreal pit stop. Right next door is another place where the tourists themselves constitute part of the attraction – Jeju Love Land (

), has achieved national fame, and though no scheduled buses run to this notorious stretch of tarmac, there’s always plenty of traffic – cars and tour buses, or indeed pencils, cans of beer or anything else capable of rolling down a hill, are said to roll upwards here. Needless to say, it’s a visual illusion created by the angles of the road and the lay of the land. Some people think it looks convincing, while others wonder why people are staring with such wonder at objects rolling down a slight incline, but it makes for a surreal pit stop. Right next door is another place where the tourists themselves constitute part of the attraction – Jeju Love Land ( ; daily 9am–midnight; W7000) is Korea’s recent sexual revolution contextualized in a theme park. This odd collection of risqué sculpture, photography and art has been immensely popular with the Koreans, now free to have a good laugh at what, for so long, was high taboo. There are statues that you can be pictured kissing or otherwise engaging with, a gallery of sexual positions (in Korean text only, but the pictures need little explanation), several erotic water features, and what may be the most bizarre of Korea’s many dioramas – a grunting plastic couple in a parked car. You may never be able to look at a hareubang in the same way, or see regal tombs as simple mounds of earth – maybe this park is the continuation of a long-running trend. Taxis cost around W10,000 from Jeju City; to get back, flag down another cab or ask around for a lift.

; daily 9am–midnight; W7000) is Korea’s recent sexual revolution contextualized in a theme park. This odd collection of risqué sculpture, photography and art has been immensely popular with the Koreans, now free to have a good laugh at what, for so long, was high taboo. There are statues that you can be pictured kissing or otherwise engaging with, a gallery of sexual positions (in Korean text only, but the pictures need little explanation), several erotic water features, and what may be the most bizarre of Korea’s many dioramas – a grunting plastic couple in a parked car. You may never be able to look at a hareubang in the same way, or see regal tombs as simple mounds of earth – maybe this park is the continuation of a long-running trend. Taxis cost around W10,000 from Jeju City; to get back, flag down another cab or ask around for a lift.

Eating, drinking and entertainment

Jeju prides itself on its seafood, and much of the city’s seafront is taken up by fish restaurants. These congregate in groups, with two of the main clusters being the large, ferry-like complex at the eastern end of the seafront promenade, and another near Yongduam rock. There’s plenty of non-fishy choice away from the water – the two best areas are the shopping district around Jungang Sagori, which contains some excellent chicken galbi restaurants, and the trendy student area west of City Hall. Most of the city’s drinking takes place in this latter area; particularly recommended are Bagdad and The Factory, a good bar. Visitors also have a chance to see Nanta, a fun musical imported from Seoul (Tues–Sun W40,000).

Bagdad Idodong. Excellent curry house with Nepali chefs and a laid-back, loungey air – particularly as the restaurant segues into a shisha bar of an evening.

Bagdad Idodong. Excellent curry house with Nepali chefs and a laid-back, loungey air – particularly as the restaurant segues into a shisha bar of an evening.

Botong Saramdeul  Ildodong. Simple Korean mains go for W4000 and under at this friendly little lair, with daily specials bringing the price down further. Chicken cutlet is a good filler, and the cold buckwheat noodle dishes (naeng-myeon) provide relief from the summer heat. The restaurant can be hard to find – look for the pink sign.

Ildodong. Simple Korean mains go for W4000 and under at this friendly little lair, with daily specials bringing the price down further. Chicken cutlet is a good filler, and the cold buckwheat noodle dishes (naeng-myeon) provide relief from the summer heat. The restaurant can be hard to find – look for the pink sign.

Daejin Hoetjip  Geonipdong. Located on the lower deck of the ferry-like “Raw Fish Town” complex, the Daejin has an English-language menu, and a decent choice for sushi experts. A huge W80,000 mixed sashimi meal could feed four, or try the delicious broiled sea bream with tofu for W10,000.

Geonipdong. Located on the lower deck of the ferry-like “Raw Fish Town” complex, the Daejin has an English-language menu, and a decent choice for sushi experts. A huge W80,000 mixed sashimi meal could feed four, or try the delicious broiled sea bream with tofu for W10,000.

Dunkin Donuts Jungang Sagori. If you’re sick to the stomach of Korean food, try these sugary antidotes from W700 per dose.

Hwanggeum Dakgalbi  Near Dongmun Rotary. Dakgalbi is a raw chicken kebab cooked at your table in a hot metal tray, which is then boiled up with a load of veggies. It costs around W9000 per portion (there’s usually a minimum of two people). When it’s nearly finished, you should then add some rice, noodles (or both) to the scraps for yet another meal.

Near Dongmun Rotary. Dakgalbi is a raw chicken kebab cooked at your table in a hot metal tray, which is then boiled up with a load of veggies. It costs around W9000 per portion (there’s usually a minimum of two people). When it’s nearly finished, you should then add some rice, noodles (or both) to the scraps for yet another meal.

Jeongdaeun Sikdang  Yongdamdong. Watch Jeju’s air traffic glide over the sea at this fish restaurant, which occupies a great location at the tip of a small peninsula between Yongduam and the Ramada Plaza. Most dishes are for groups of three or four (W10,000–15,000 per person); solo diners may have to content themselves with the Hoe-deopbap – raw fish in spicy sauce on a bed of rice.

Yongdamdong. Watch Jeju’s air traffic glide over the sea at this fish restaurant, which occupies a great location at the tip of a small peninsula between Yongduam and the Ramada Plaza. Most dishes are for groups of three or four (W10,000–15,000 per person); solo diners may have to content themselves with the Hoe-deopbap – raw fish in spicy sauce on a bed of rice.

Segeomjeong  Dongmun Rotary. Low, low prices mean that this meat restaurant is almost permanently full. The menu is little more than a list of flesh to barbecue, including saeng galbi and the saucier yangnyeom galbi.

Dongmun Rotary. Low, low prices mean that this meat restaurant is almost permanently full. The menu is little more than a list of flesh to barbecue, including saeng galbi and the saucier yangnyeom galbi.

Tap  Geonipdong; look for the Chinese sign

Geonipdong; look for the Chinese sign  . Soju flows freely into the early hours at this stylish, wood-panelled restaurant as students set fire to, then eat, a variety of meats. Samgyeopsal (pork belly) goes for W8000 per portion, with gimchi fried rice a cheap extra.

. Soju flows freely into the early hours at this stylish, wood-panelled restaurant as students set fire to, then eat, a variety of meats. Samgyeopsal (pork belly) goes for W8000 per portion, with gimchi fried rice a cheap extra.

Zapata’s Idodong. The tacos, burritos and quesadillas at this small Mexican restaurant go down well with travellers, and prices are good at W4000–9000 per portion. The owners seem to assume that foreigners can’t handle spicy food, so you may have to ask for extra chilli.

Listings

Bike rental The Lespo Mart, just town-side of Chinjeol Minbak on the same side of the road, rents out decent bikes for W7000 per day; you’ll need your passport to leave behind as security. Yeha Guesthouse rents out bikes (guests only) for W5000 per day.

Car rental Several companies at the city airport. Rates start at around W35,000 per day.

Cinema The Academy Cinema, in a large complex a short walk south of Mokgwanaji, is the best place to catch a film; tickets cost W7000.

Hiking equipment There are stores all over the city, especially in the shopping area around Jungang Sagori. Prices are higher than you might expect, but Treksta is a fairly safe choice.

Hospital The best place for foreigners is the Jeju University hospital ( 064/750-1234); call

064/750-1234); call  119 in an emergency.

119 in an emergency.

Internet In addition to the usual cafés dotted around the city there are also free booths in the ferry and bus terminals.

Motorbike rental Jeju Bike, near the bus station, has motorcycles and scooters to hire or sell, and an English-speaking owner ( 064/758-5296).

064/758-5296).

Post office Post offices across the island are open weekdays from 9am–5pm, with the central post office ( 064/758-8602), near Mokgwanaji, also open on Saturdays until 1pm.

064/758-8602), near Mokgwanaji, also open on Saturdays until 1pm.

Eastern Jeju

The eastern half of Jeju is wonderfully unspoilt – the coast is dotted with unhurried fishing villages, while inland you can see evidence of Jeju’s turbulent creation in the form of lava tubes and volcanic craters. Buses to the region leave Jeju City with merciful swiftness, passing between the sea and lush green fields, the latter bordered by stacks of batdam. Seongsan, on the island’s eastern tip, is the most attractive of Jeju’s many small villages, crowned by the majestic caldera of Ilchulbong.

Just offshore is Udo, a bucolic island whose sedentary pace tempts many a visitor to hole up for a few days. A cluster of natural attractions can be found south of the port village of Gimnyeong, most notably Manjanggul, which are some of the world’s longest underground lava tubes. Further south again, Route 97 heads southeast from Jeju City across the island’s interior, running past Sangumburi, a large, forested volcanic crater, and two rewarding folk villages: one a working community with a patchwork of traditional thatch-roofed houses, the other an open-air museum which – though devoid of inhabitants – provides a little more instruction on traditional Jeju life.

Seongsan

You’re unlikely to be disappointed by SEONGSAN ( ), an endearing rural town with one very apparent tourist draw looming over it: Ilchulbong (

), an endearing rural town with one very apparent tourist draw looming over it: Ilchulbong ( ), or “Sunrise Peak”, is so named as it’s the first place on the island to be lit up by the orange fires of dawn. The town can easily be visited as a day-trip from Jeju City but many visitors choose to spend a night here, beating the sun out of bed to clamber up the graceful, green slope to the rim of Ilchulbong’s crown-shaped caldera (24hr; W2000). It’s an especially popular place for Koreans to ring in the New Year – a small festival celebrates the changing of the digits. From the town it’s a twenty-minute or so walk to the summit; a steep set of steps leads up to a 182m-high viewing platform at the top, and although the island’s fickle weather and morning mists usually conspire to block the actual emergence of the sun from the sea, it’s a splendid spot nonetheless. Powerful bulbs from local squid boats dot the nearby waters; as the morning light takes over, the caldera below reveals itself as beautifully verdant, its far side plunging sheer into the sea – unfortunately, it’s not possible to hike around the rim. If you turn to face west, Seongsan is visible below, and the topography of the surrounding area – hard to judge from ground level – reveals itself.

), or “Sunrise Peak”, is so named as it’s the first place on the island to be lit up by the orange fires of dawn. The town can easily be visited as a day-trip from Jeju City but many visitors choose to spend a night here, beating the sun out of bed to clamber up the graceful, green slope to the rim of Ilchulbong’s crown-shaped caldera (24hr; W2000). It’s an especially popular place for Koreans to ring in the New Year – a small festival celebrates the changing of the digits. From the town it’s a twenty-minute or so walk to the summit; a steep set of steps leads up to a 182m-high viewing platform at the top, and although the island’s fickle weather and morning mists usually conspire to block the actual emergence of the sun from the sea, it’s a splendid spot nonetheless. Powerful bulbs from local squid boats dot the nearby waters; as the morning light takes over, the caldera below reveals itself as beautifully verdant, its far side plunging sheer into the sea – unfortunately, it’s not possible to hike around the rim. If you turn to face west, Seongsan is visible below, and the topography of the surrounding area – hard to judge from ground level – reveals itself.

Besides the conquest of Ilchulbong, there’s little to do in Seongsan bar strolling around the neighbouring fields and tucking into a fish supper, though the waters off the coast do offer some fantastic diving opportunities. South of town is Sinyang Beach, where the water depth and incessant wind make it a good place to windsurf; equipment is available to rent.

Practicalities

Minbak and fish restaurants can be found in abundance, but anybody wanting higher-end accommodation, or meat not culled from the sea, may have a hard time. Simple rooms are easy to find – alternatively, hang around and wait for the ajummas to find you – and are split into two main areas: those peak-side of the main road, which tend to be tiny and bunched in tight clusters, or those in the fields facing Hallasan, which are generally located in family homes, and are slightly cleaner. A bit of haggling should see the prices drop to W15,000–20,000. Comfier rooms can be found at the Condominium-style Minbak ( ;

;  064/784-8940;

064/784-8940;  ), in a big blue building at the southern edge of town, above a ground-floor restaurant. Rooms here are adequate, and some have internet access; try to nab one with a balcony facing Ilchulbong. Sinyang beach, a few kilometres to the south, also has plenty of rooms for rent, though prices rise sharply during the summer holidays. Coffee and snacks are available from a 24-hour convenience store near the Ilchulbong ticket booth.

), in a big blue building at the southern edge of town, above a ground-floor restaurant. Rooms here are adequate, and some have internet access; try to nab one with a balcony facing Ilchulbong. Sinyang beach, a few kilometres to the south, also has plenty of rooms for rent, though prices rise sharply during the summer holidays. Coffee and snacks are available from a 24-hour convenience store near the Ilchulbong ticket booth.

Sealife Scuba ( 064/782-1150), near Kondohyeong Minbak, offers spectacular diving trips for around W150,000 per person, equipment included.

064/782-1150), near Kondohyeong Minbak, offers spectacular diving trips for around W150,000 per person, equipment included.

Visible from Ilchulbong is UDO ( ), a rural speck of land whose stacked-stone walls and rich grassy hills give it the air of a Scottish isle transported to warmer climes. Occasionally, the nomenclature of Korea’s various peaks and stony bits reaches near-Dadaist extremes; “Cow Island” is one of the best examples, its contours apparently resembling the shape of resting cattle. This sparsely populated dollop of land is a wonderful place to hole up for a few days, and one of the best places to spot two of Jeju’s big draws – the stone walls (

), a rural speck of land whose stacked-stone walls and rich grassy hills give it the air of a Scottish isle transported to warmer climes. Occasionally, the nomenclature of Korea’s various peaks and stony bits reaches near-Dadaist extremes; “Cow Island” is one of the best examples, its contours apparently resembling the shape of resting cattle. This sparsely populated dollop of land is a wonderful place to hole up for a few days, and one of the best places to spot two of Jeju’s big draws – the stone walls ( ; batdam) that line the island’s fields and narrow roads, and the haenyeo, female divers long famed for their endurance.

; batdam) that line the island’s fields and narrow roads, and the haenyeo, female divers long famed for their endurance.

Other than these – and the diving grannies are almost impossible to spot these days – there are very few tourist sights on Udo. Those that do exist can be accessed on the tour buses (W5000) that meet the ferries. Usually under the direction of charismatic local drivers, they first stop at a black-sand beach for half an hour or so, which allows just enough time to scamper up the hill to the lighthouse for amazing views that show just how rural Udo really is. The buses stop at a small natural history museum (Tues–Sun 9am–5pm; W2000, free entry with bus ticket) – whose second floor is home to some interesting haenyeo paraphernalia – and continue past Sanhosa beach before returning to the ferry terminal.

Arrival and getting around

Udo is reached on regular ferries (W5500 return) from Seongsan port, which is within walking distance of the town itself. These dock at one of two terminals, so on arrival it may come in handy to note what time the ferries return; if you’re staying the night, your accommodation will advise on which terminal to head to.

Tour buses are the easiest way to get around, but infinitely more enjoyable are the scooters (W10,000/2hr) and buggies (double that) available for rent outside both ferry terminals. Udo is so small that it’s hard to get lost, and most simply fire around the island’s near-empty lanes until it’s time to return their vehicle. Don’t worry if you’re a bit late – this is Udo, after all.

It may be hard to believe in a place that once was, and in many ways still is, the most Confucian country on earth, but for a time areas of Jeju had matriarchal social systems. This role reversal is said to have begun in the nineteenth century as a form of tax evasion, when male divers found a loophole in the law that exempted them from tax if their wives did the work. So were born the haenyeo ( ), literally “sea women”; while their husbands cared for the kids and did the shopping, the females often became the breadwinners, diving without breathing apparatus for minutes at a time in search of shellfish and sea urchins. With women traditionally seen as inferior, this curious emancipation offended the country’s leaders, who sent delegates from Seoul in an attempt to ban the practice. It didn’t help matters that the haenyeo performed their duties clad only in loose white cotton, and it was made illegal for men to lay eyes on them as they worked.

), literally “sea women”; while their husbands cared for the kids and did the shopping, the females often became the breadwinners, diving without breathing apparatus for minutes at a time in search of shellfish and sea urchins. With women traditionally seen as inferior, this curious emancipation offended the country’s leaders, who sent delegates from Seoul in an attempt to ban the practice. It didn’t help matters that the haenyeo performed their duties clad only in loose white cotton, and it was made illegal for men to lay eyes on them as they worked.

Today, the haenyeo are one of Jeju’s most famous sights. Folk songs have been written about them, their statues dot the shores, and one can buy postcards, mugs and plates decorated with dripping sea sirens rising from the sea. This romantic vision, however, is not entirely current; the old costumes have now given way to black wetsuits, and the haenyeo have grown older: even tougher than your average ajumma, many have continued to dive into their 70s. Modern life is depleting their numbers – there are easier ways to make money now, and few families are willing to encourage their daughters into what is still a dangerous profession. The figures peaked in the 1950s at around thirty thousand, but at the last count there were just a few hundred practising divers, the majority aged over 50. Before long, the tradition may well become one of Jeju’s hard-to-believe myths.

Minbak are readily available, though the rural ambience comes at a slightly higher price than you’d pay in Seongsan; prices are around W30,000 per night. The only truly notable one is  Deungmeoeul (

Deungmeoeul ( ;

;  064/784-3878;

064/784-3878;  Mobile 011/341-3604;

Mobile 011/341-3604;  ), which is actually located on an even smaller island, connected to Udo by a small bridge. This is tiny Biyangdo (

), which is actually located on an even smaller island, connected to Udo by a small bridge. This is tiny Biyangdo ( ), formerly an important haenyeo hangout but now down to a population of just two – a friendly couple who run the minbak, speak a little English, and will collect you from the ferry terminal if you give them a call. Back across the bridge is Udo’s best restaurant, Haewa Dal Geurigo Seom (

), formerly an important haenyeo hangout but now down to a population of just two – a friendly couple who run the minbak, speak a little English, and will collect you from the ferry terminal if you give them a call. Back across the bridge is Udo’s best restaurant, Haewa Dal Geurigo Seom ( ), which specializes in colossal, fist-sized sea snails called sora (

), which specializes in colossal, fist-sized sea snails called sora ( ; W20,000 per portion). You’ll find other restaurants near the ferry terminals and above the black-sand beach.

; W20,000 per portion). You’ll find other restaurants near the ferry terminals and above the black-sand beach.

Manjanggul

A short way east of Jeju City, a group of natural attractions provide an enjoyable day-trip. Foremost among them is Manjanggul ( ; daily: April–Oct 9am–6pm; Nov–March 9am–5pm; W2000), a long underground cave formed by pyroclastic flows. Underwater eruptions millions of years ago caused channels of surface lava to crust over or burrow into the soft ground, resulting in subterranean tunnels of flowing lava. Once the flow finally stopped, these so-called “lava tubes” remained. Stretching for at least 9km beneath the fields and forests south of the small port of Gimnyeong, Manjanggul is one of the longest such systems in the world, though only 1km or so is open to the public. This dingy and damp “tube” contains a number of hardened, lava features including balls, bridges and an 8m-high pillar at the end of the course.

; daily: April–Oct 9am–6pm; Nov–March 9am–5pm; W2000), a long underground cave formed by pyroclastic flows. Underwater eruptions millions of years ago caused channels of surface lava to crust over or burrow into the soft ground, resulting in subterranean tunnels of flowing lava. Once the flow finally stopped, these so-called “lava tubes” remained. Stretching for at least 9km beneath the fields and forests south of the small port of Gimnyeong, Manjanggul is one of the longest such systems in the world, though only 1km or so is open to the public. This dingy and damp “tube” contains a number of hardened, lava features including balls, bridges and an 8m-high pillar at the end of the course.

Buses run south past the cave to Bijarim Forest ( ), a family-friendly network of trails and tall trees. Heading the other way, north of the cave and maze, small but busy Gimnyeong Beach has the area’s greatest concentration of restaurants and accommodation, and is accessible on the buses that run along the coastal road.

), a family-friendly network of trails and tall trees. Heading the other way, north of the cave and maze, small but busy Gimnyeong Beach has the area’s greatest concentration of restaurants and accommodation, and is accessible on the buses that run along the coastal road.

With a volcanic crater to see and two folk villages to explore, rural Route 97 – also known as the East Tourist Road – is a delightful way to cut through Jeju’s interior. All three attractions can be visited on a day-trip from Jeju City, or as part of a journey between the capital and Seogwipo on the south coast, though it pays to start reasonably early.

Sangumburi

Heading south from Jeju City on Route 97, the first place worth stopping is Sangumburi ( ; daily 9am–7pm; W3000), one of Jeju’s many volcanic craters; possibly its most impressive, certainly its most accessible, though currently the only one you have to pay to visit. Hole lovers should note that this particular type is known as a Marr crater, as it was produced by an explosion in a generally flat area. One can only imagine how big an explosion it must have been – the crater, 2km in circumference and 132m deep, is larger than Hallasan’s. A short climb to the top affords sweeping views of some very unspoilt Jejanese terrain; peaks rise in all directions, with Hallasan 20km to the southwest, though not always visible. The two obvious temptations are to walk into or around the rim, but you must refrain from doing so in order to protect the crater’s wildlife – deer and badgers are among the species that live in Sangumburi. Consequently there’s not an awful lot to do here, though there’s a small art gallery on site. Buses (W1800) take around 25 minutes to get here from the terminal in Jeju City; note that most East Tourist Road buses miss Sangumburi, with only one an hour coming here. If you’re continuing south the next bus will arrive approximately an hour after your arrival – stand on the main road to flag it down, but keep an eye out, as it’ll come by in a flash.

; daily 9am–7pm; W3000), one of Jeju’s many volcanic craters; possibly its most impressive, certainly its most accessible, though currently the only one you have to pay to visit. Hole lovers should note that this particular type is known as a Marr crater, as it was produced by an explosion in a generally flat area. One can only imagine how big an explosion it must have been – the crater, 2km in circumference and 132m deep, is larger than Hallasan’s. A short climb to the top affords sweeping views of some very unspoilt Jejanese terrain; peaks rise in all directions, with Hallasan 20km to the southwest, though not always visible. The two obvious temptations are to walk into or around the rim, but you must refrain from doing so in order to protect the crater’s wildlife – deer and badgers are among the species that live in Sangumburi. Consequently there’s not an awful lot to do here, though there’s a small art gallery on site. Buses (W1800) take around 25 minutes to get here from the terminal in Jeju City; note that most East Tourist Road buses miss Sangumburi, with only one an hour coming here. If you’re continuing south the next bus will arrive approximately an hour after your arrival – stand on the main road to flag it down, but keep an eye out, as it’ll come by in a flash.

Seong-eup Folk Village

A twenty-minute bus ride south of Sangumburi brings you to dusty Seong-eup Folk Village ( ), a functioning community living in traditional Jeju-style housing, where you’re free to wander among the thatch-roofed houses at will; the residents, given financial assistance by the government, are long used to curious visitors nosing around their yards. Here you’ll see life carrying on as if nothing had changed in decades – farmers going about their business and children playing while crops sway in the breeze. Most visitors spend a couple of pleasant hours here, and if you’re lucky you’ll run into one of the few English-speaking villagers, who act as guides.

), a functioning community living in traditional Jeju-style housing, where you’re free to wander among the thatch-roofed houses at will; the residents, given financial assistance by the government, are long used to curious visitors nosing around their yards. Here you’ll see life carrying on as if nothing had changed in decades – farmers going about their business and children playing while crops sway in the breeze. Most visitors spend a couple of pleasant hours here, and if you’re lucky you’ll run into one of the few English-speaking villagers, who act as guides.

Though there’s nowhere to stay, there are a few restaurants around the village; best is Tamna Sikdang ( ), who serve tasty set meals of black pork and side dishes (heukdwaeji jeongsik;

), who serve tasty set meals of black pork and side dishes (heukdwaeji jeongsik;  ) for W8000 per head, and make their own makkeolli. Buses to the village take around 45min from Jeju City, and almost all continue on to Jeju Folk Village.

) for W8000 per head, and make their own makkeolli. Buses to the village take around 45min from Jeju City, and almost all continue on to Jeju Folk Village.

Jeju Folk Village and around

Route 97 buses terminate near the coast at the Jeju Folk Village ( ; daily: April–Sept 8.30am–6pm; Oct–March 8.30am–5pm; W6000). This coastal clutch of traditional Jeju buildings may be artificial, but provides an excellent complement to the Seong-eup village to its north. Information boards explain the layout and structures of the buildings, as well as telling you what the townsfolk used to get up to before selling tea and baggy orange pants to tourists. The differences between dwellings on different parts of the island are subtle but interesting – the island’s southerners, for example, entwined ropes outside their door with red peppers if a boy had been born into their house. However, the buildings may all start to look a little samey without the help of an English-language audio guide (W2000; available from a hidden office behind the ticket booth). There’s a cluster of restaurants near the exit, though for accommodation you’ll have to take a short walk to the nearby coastal town of Pyoseon. The best place to stay is the Beach Park Motel (

; daily: April–Sept 8.30am–6pm; Oct–March 8.30am–5pm; W6000). This coastal clutch of traditional Jeju buildings may be artificial, but provides an excellent complement to the Seong-eup village to its north. Information boards explain the layout and structures of the buildings, as well as telling you what the townsfolk used to get up to before selling tea and baggy orange pants to tourists. The differences between dwellings on different parts of the island are subtle but interesting – the island’s southerners, for example, entwined ropes outside their door with red peppers if a boy had been born into their house. However, the buildings may all start to look a little samey without the help of an English-language audio guide (W2000; available from a hidden office behind the ticket booth). There’s a cluster of restaurants near the exit, though for accommodation you’ll have to take a short walk to the nearby coastal town of Pyoseon. The best place to stay is the Beach Park Motel ( 064/7877-9556;

064/7877-9556;  ), on the junction of Route 12 and the folk village access road, which has decent new rooms, though few face the large beach that sits across the road. Buses from Pyoseon to Seogwipo run from a road a few blocks further uphill – ask for directions. En route, near the town of Namwon, is the Sinyoung Cinema Museum (Tues–Sun 9am–6.30pm; W6000), set in a highly distinctive building whose whitewashed walls and coastal setting carry faint Mediterranean echoes. Its contents are mildly diverting – old projectors and the like – though perhaps most appealing are the surrounding gardens.

), on the junction of Route 12 and the folk village access road, which has decent new rooms, though few face the large beach that sits across the road. Buses from Pyoseon to Seogwipo run from a road a few blocks further uphill – ask for directions. En route, near the town of Namwon, is the Sinyoung Cinema Museum (Tues–Sun 9am–6.30pm; W6000), set in a highly distinctive building whose whitewashed walls and coastal setting carry faint Mediterranean echoes. Its contents are mildly diverting – old projectors and the like – though perhaps most appealing are the surrounding gardens.

Jeju traditions

Essentially a frozen piece of the past, Seong-eup Folk Village is a wonderful place to get a handle on Jeju’s ancient traditional practices, but you’ll see evidence of these age-old activities all over the island. Many locals still wear galot ( ), comfy Jejanese costumes of apricot-dyed cotton or hemp; these are available to buy in Seong-eup, though you’ll also find them for sale outside most Jeju sights. Local homes are separated from each other with batdam (

), comfy Jejanese costumes of apricot-dyed cotton or hemp; these are available to buy in Seong-eup, though you’ll also find them for sale outside most Jeju sights. Local homes are separated from each other with batdam ( ), gorgeous walls of hand-stacked volcanic rock built with no adhesive whatsoever – ironically, this actually affords protection against Jeju’s occasionally vicious winds, which whip straight through the gaps. The homes themselves are also traditional in nature, with thatched roofs and near-identical gates consisting of three wooden bars, poked through holes in two stone side-columns. This is a quaint local communication system known as jeongnang (

), gorgeous walls of hand-stacked volcanic rock built with no adhesive whatsoever – ironically, this actually affords protection against Jeju’s occasionally vicious winds, which whip straight through the gaps. The homes themselves are also traditional in nature, with thatched roofs and near-identical gates consisting of three wooden bars, poked through holes in two stone side-columns. This is a quaint local communication system known as jeongnang ( ), unique to Jeju and still used today – when all bars are up, the owner of the house is not home, one bar up means that they’ll be back soon, and if all three are down, you’re free to walk on in. Some houses still have a traditional open-air Jeju toilet in their yard; these were located above the pig enclosures so that the family hogs could transform human waste into their own, which could then be used as fertiliser. Needless to say, no locals now use these toilets – traditional, for sure, but some things are best left in the past.

), unique to Jeju and still used today – when all bars are up, the owner of the house is not home, one bar up means that they’ll be back soon, and if all three are down, you’re free to walk on in. Some houses still have a traditional open-air Jeju toilet in their yard; these were located above the pig enclosures so that the family hogs could transform human waste into their own, which could then be used as fertiliser. Needless to say, no locals now use these toilets – traditional, for sure, but some things are best left in the past.

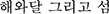

The charming town of SEOGWIPO ( ) sits sunny-side-up on Jeju’s fair southern coast: whereas days in Jeju City and on the northern coast are curtailed when the sun drops beneath Hallasan’s lofty horizon, the south coast has no such impediment. Evidence of this extra light can be seen in the tangerine groves that start just outside the city and are famed across Korea. Though the real attraction here is the chance to kick back and unwind, there are a few things to see and do – gorgeous waterfalls flank the city, while water-based activities range from diving to submarine tours.

) sits sunny-side-up on Jeju’s fair southern coast: whereas days in Jeju City and on the northern coast are curtailed when the sun drops beneath Hallasan’s lofty horizon, the south coast has no such impediment. Evidence of this extra light can be seen in the tangerine groves that start just outside the city and are famed across Korea. Though the real attraction here is the chance to kick back and unwind, there are a few things to see and do – gorgeous waterfalls flank the city, while water-based activities range from diving to submarine tours.

Arrival, information and tours

There are several bus routes across the island from Jeju City, all stopping in Seogwipo’s new bus station, inconveniently located several kilometres east of the city centre, near the World Cup Stadium. Buses on routes heading east of Hallasan usually make a stop by the old station in central Seogwipo – get off when the driver tells you to.

The main tourist office (daily 9am–6pm;  064/732-1330) is at the entrance to Cheonjiyeon, a waterfall just west of the centre. Follow the stream out towards the sea, on the same side as the ticket booth, and before long you’ll come to the launch point for a submarine tour (every 45min; W50,000). The subs dive down to 35m, allowing glimpses of colourful coral and marine life, including octopus, clownfish and the less familiar “stripey footballer”. You could also take a boat trip around the coast and offshore islets; check with the tourist office for details. Diving around the same islands is also popular; Big Blue, a German-run operation (

064/732-1330) is at the entrance to Cheonjiyeon, a waterfall just west of the centre. Follow the stream out towards the sea, on the same side as the ticket booth, and before long you’ll come to the launch point for a submarine tour (every 45min; W50,000). The subs dive down to 35m, allowing glimpses of colourful coral and marine life, including octopus, clownfish and the less familiar “stripey footballer”. You could also take a boat trip around the coast and offshore islets; check with the tourist office for details. Diving around the same islands is also popular; Big Blue, a German-run operation ( 064/733-1733;

064/733-1733;  www.bigblue33.co.kr), offers a range of courses starting at W95,000 per person. Several places rent motorbikes (from around W30,000 per day); your accommodation will have pamphlets directing you to the nearest.

www.bigblue33.co.kr), offers a range of courses starting at W95,000 per person. Several places rent motorbikes (from around W30,000 per day); your accommodation will have pamphlets directing you to the nearest.

Accommodation

Seogwipo has a range of accommodation to suit all budgets. However, since the closure of the wonderful old Paradise Hotel (two years ago and counting at the time of writing, though with plans to reopen at some point), the city’s higher-end hotels are poor value. There are better pickings further down the price scale, as well as plenty of motels; camping by Oedolgae rock is another possibility, or for a cheap and slightly bizarre place to stay, there’s a jjimjilbang (W8000) in the World Cup Stadium to the west of the city.

Jeju Hiking Inn Seogwidong  064/763-2380. This quasi-hostel gets mixed reviews, thanks to often smelly corridors and the incredible number of mosquitos that haunt the free internet room in summer. However, the rooms are comfy enough, with passable bathrooms, and you can rent bicycles for W10,000 per day.

064/763-2380. This quasi-hostel gets mixed reviews, thanks to often smelly corridors and the incredible number of mosquitos that haunt the free internet room in summer. However, the rooms are comfy enough, with passable bathrooms, and you can rent bicycles for W10,000 per day.

KAL Hotel Topyeongdong  064/733-2001,

064/733-2001,  www.kalhotel.co.kr. As with its sister hotel in Jeju City, this is a very businesslike tower that stands proudly over its surroundings. It’s immaculate – a little too clinical for some – and the grounds are beautiful. There’s also a tennis court, a jogging track, and various on-site restaurants and cafés.

www.kalhotel.co.kr. As with its sister hotel in Jeju City, this is a very businesslike tower that stands proudly over its surroundings. It’s immaculate – a little too clinical for some – and the grounds are beautiful. There’s also a tennis court, a jogging track, and various on-site restaurants and cafés.

Little France Seogwidong

Little France Seogwidong  064/732-4552,

064/732-4552,  www.littlefrancehotel.co.kr. Vaguely European in feel, this chic hotel is a real find. Views aren’t amazing but the rooms are bright and fresh, created with a warmth rarely evident in Korean accommodation.

www.littlefrancehotel.co.kr. Vaguely European in feel, this chic hotel is a real find. Views aren’t amazing but the rooms are bright and fresh, created with a warmth rarely evident in Korean accommodation.

Shinsegae Jeongbangdong  064/732-5800. Officially a hotel, but in reality a less-seedy-than-average motel, this is a great cheapie. Some rooms have internet-ready computer terminals, and others pleasant ocean views.

064/732-5800. Officially a hotel, but in reality a less-seedy-than-average motel, this is a great cheapie. Some rooms have internet-ready computer terminals, and others pleasant ocean views.

Sun Beach Seogwidong  064/732-5678,

064/732-5678,  www.hotelsunbeach.co.kr. The better of two shabby hotels uphill from Cheonjiyeon waterfall. Six floors of mostly stained red carpet lead to rooms that are only good value with off-season discounts of up to fifty percent.

www.hotelsunbeach.co.kr. The better of two shabby hotels uphill from Cheonjiyeon waterfall. Six floors of mostly stained red carpet lead to rooms that are only good value with off-season discounts of up to fifty percent.

Tae Gong Gak Seogwidong

Tae Gong Gak Seogwidong  064/762-2623. Homely little place with simple private rooms and a kitchenette for making your own meals. The real bonus here is the super-friendly staff, who are full of handy advice.

064/762-2623. Homely little place with simple private rooms and a kitchenette for making your own meals. The real bonus here is the super-friendly staff, who are full of handy advice.

The waterfalls

Most of Jeju’s rainfall is swallowed up by the porous volcanic rock that forms much of the island, but a couple of waterfalls spill into the sea either side of Seogwipo city centre. To the east is Jeongbang ( ; 7.30am–6pm; W2000), a 23m-high cascade claimed to be the only one in Asia to fall directly into the ocean. Unique or not, once you’ve clambered down to ground level it’s an impressive sight, especially when streams are swollen by the summer monsoon, at which time it’s impossible to get close without being drenched by spray. Look for some Chinese characters on the right-hand side of the falls – their meaning is explained by an unintentionally comical English-language cartoon in an otherwise dull exhibition hall above the falls.

; 7.30am–6pm; W2000), a 23m-high cascade claimed to be the only one in Asia to fall directly into the ocean. Unique or not, once you’ve clambered down to ground level it’s an impressive sight, especially when streams are swollen by the summer monsoon, at which time it’s impossible to get close without being drenched by spray. Look for some Chinese characters on the right-hand side of the falls – their meaning is explained by an unintentionally comical English-language cartoon in an otherwise dull exhibition hall above the falls.

The western fall, Cheonjiyeon ( ; daily: April–Oct 8am–11pm; Nov–March 8am–10pm; W2000), is shorter but wider than Jeongbang, and sits at the end of a pleasant gorge that leads from the ticket office, downhill from the city centre: take the path starting opposite Jeju Hiking Inn. Many prefer to visit at night, when there are fewer visitors and the paths up to the gorge are bathed in dim light.

; daily: April–Oct 8am–11pm; Nov–March 8am–10pm; W2000), is shorter but wider than Jeongbang, and sits at the end of a pleasant gorge that leads from the ticket office, downhill from the city centre: take the path starting opposite Jeju Hiking Inn. Many prefer to visit at night, when there are fewer visitors and the paths up to the gorge are bathed in dim light.

Other sights

In the centre is an interesting gallery ( ; Tues–Sun: July–Sept 9am–8pm; Oct–June 9am–6pm; W1000) devoted to the works of Lee Joong-seop (1916–56), who used to live in what are now the gallery’s grounds. During the Korean War, he made a number of pictures on silver paper from cigarette boxes, which now take centre stage in a small but impressive collection of local modern art. Many of Lee’s pieces echo the gradual breakdown of his private life, which culminated in his early demise. Just down the road from the gallery is Mirunamu, Seogwipo’s most characterful café.

; Tues–Sun: July–Sept 9am–8pm; Oct–June 9am–6pm; W1000) devoted to the works of Lee Joong-seop (1916–56), who used to live in what are now the gallery’s grounds. During the Korean War, he made a number of pictures on silver paper from cigarette boxes, which now take centre stage in a small but impressive collection of local modern art. Many of Lee’s pieces echo the gradual breakdown of his private life, which culminated in his early demise. Just down the road from the gallery is Mirunamu, Seogwipo’s most characterful café.

West of the city centre is the “Lonely Rock” of Oedolgae ( ). This stone pinnacle jutting out of the sea just off the coast is an impressive sight at sunset, when locals fish by the waters and the column is bathed in radiant hues. Buses (#200 and #300) run here from the city centre, but a taxi shouldn’t cost more than W4000. Camping is possible along the network of trails that lead through the pines from the bus stop to the rock, below a shop-cum-café with an outdoor seating area.

). This stone pinnacle jutting out of the sea just off the coast is an impressive sight at sunset, when locals fish by the waters and the column is bathed in radiant hues. Buses (#200 and #300) run here from the city centre, but a taxi shouldn’t cost more than W4000. Camping is possible along the network of trails that lead through the pines from the bus stop to the rock, below a shop-cum-café with an outdoor seating area.

A number of appealing restaurants, some with great views, line the sides of the estuary leading up to Cheonjiyeon, though the greatest concentration can be found south of the Jungjeongno-Jungangno junction. Kimbap Cheon-guk (

) by this crossroads dishes out simple but consistent Korean staples at low prices, but a better recommendation is