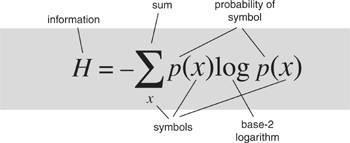

It defines how much information a message contains, in terms of the probabilities with which the symbols that make it up are likely to occur.

It is the equation that ushered in the information age. It established limits on the efficiency of communications, allowing engineers to stop looking for codes that were too effective to exist. It is basic to today’s digital communications – phones, CDs, DVDs, the internet.

Efficient error-detecting and error-correcting codes, used in everything from CDs to space probes. Applications include statistics, artificial intelligence, cryptography, and extracting meaning from DNA sequences.

In 1977 NASA launched two space probes, Voyager 1 and 2. The planets of the Solar System had arranged themselves in unusually favourable positions, making it possible to find reasonably efficient orbits that would let the probes visit several planets. The initial aim was to examine Jupiter and Saturn, but if the probes held out, their trajectories would take them on past Uranus and Neptune. Voyager 1 could have gone to Pluto (at that time considered a planet, and equally interesting – indeed totally unchanged – now that it’s not) but an alternative, Saturn’s intriguing moon Titan, took precedence. Both probes were spectacularly successful, and Voyager 1 is now the most distant human-made object from Earth, more than 10 billion miles away and still sending back data.

Signal strength falls off with the square of the distance, so the signal received on Earth is 10–20 times the strength that it would be if received from a distance of one mile. That is, one hundred quintillion times weaker. Voyager 1 must have a really powerful transmitter … No, it’s a tiny space probe. It is powered by a radioactive isotope, plutonium-238, but even so the total power available is now about one eighth that of a typical electric kettle. There are two reasons why we can still obtain useful information from the probe: powerful receivers on Earth, and special codes used to protect the data from errors caused by extraneous factors such as interference.

Voyager 1 can send data using two different systems. One, the low-rate channel, can send 40 binary digits, 0s or 1s, every second, but it does not allow coding to deal with potential errors. The other, the high-rate channel, can transmit up to 120,000 binary digits every second, and these are encoded so that errors can be spotted and put right provided they’re not too frequent. The price paid for this ability is that the messages are twice as long as they would otherwise be, so they carry only half as much data as they could. Since errors could ruin the data, this is a price worth paying.

Codes of this kind are widely used in all modern communications: space missions, landline phones, mobile phones, the Internet, CDs and DVDs, Blu-ray, and so on. Without them, all communications would be liable to errors; this would not be acceptable if, for instance, you were using the Internet to pay a bill. If your instruction to pay £20 was received as £200, you wouldn’t be pleased. A CD player uses a tiny lens, which focuses a laser beam on to very thin tracks impressed in the material of the disc. The lens hovers a very tiny distance above the spinning disc. Yet you can listen to a CD while driving along a bumpy road, because the signal is encoded in a way that allows errors to be found and put right by the electronics while the disc is being played. There are other tricks, too, but this one is fundamental.

Our information age relies on digital signals – long strings of 0s and 1s, pulses and non-pulses of electricity or radio. The equipment that sends, receives, and stores the signals relies on very small, very precise electronic circuits on tiny slivers of silicon – ‘chips’. But for all the cleverness of the circuit design and manufacture, none of it would work without error-detecting and error-correcting codes. And it was in this context that the term ‘information’ ceased to be an informal word for ‘know-how’, and became a measurable numerical quantity. And that provided fundamental limitations on the efficiency with which codes can modify messages to protect them against errors. Knowing these limitations saved engineers lots of wasted time, trying to invent codes that would be so efficient they’d be impossible. It provided the basis for today’s information culture.

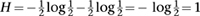

I’m old enough to remember when the only way to telephone someone in another country (shock horror) was to make a booking ahead of time with the phone company – in the UK there was only one, Post Office Telephones – for a specific time and length. Say ten minutes at 3.45 p.m. on 11 January. And it cost a fortune. A few weeks ago a friend and I did an hour-long interview for a science fiction convention in Australia, from the United Kingdom, using SkypeTM. It was free, and it sent video as well as sound. A lot has changed in fifty years. Nowadays, we exchange information online with friends, both real ones and the phonies that large numbers of people collect like butterflies using social networking sites. We no longer buy music CDs or movie DVDs: we buy the information that they contain, downloaded over the Internet. Books are heading the same way. Market research companies amass huge quantities of information about our purchasing habits and try to use it to influence what we buy. Even in medicine, there is a growing emphasis on the information that is contained in our DNA. Often the attitude seems to be that if you have the information required to do something, then that alone suffices; you don’t need actually to do it, or even know how to do it.

There is little doubt that the information revolution has transformed our lives, and a good case can be made that in broad terms the benefits outweigh the disadvantages – even though the latter include loss of privacy, potential fraudulent access to our bank accounts from anywhere in the word at the click of a mouse, and computer viruses that can disable a bank or a nuclear power station.

What is information? Why does it have such power? And is it really what it is claimed to be?

The concept of information as a measurable quantity emerged from the research laboratories of the Bell Telephone Company, the main provider of telephone services in the United States from 1877 to its break-up in 1984 on anti-trust (monopoly) grounds. Among its engineers was Claude Shannon, a distant cousin of the famous inventor Edison. Shannon’s best subject at school was mathematics, and he had an aptitude for building mechanical devices. By the time he was working for Bell Labs he was a mathematician and cryptographer, as well as an electronic engineer. He was one of the first to apply mathematical logic – so-called Boolean algebra – to computer circuits. He used this technique to simplify the design of switching circuits used by the telephone system, and then extended it to other problems in circuit design.

During World War II he worked on secret codes and communications, and developed some fundamental ideas that were reported in a classified memorandum for Bell in 1945 under the title ‘A mathematical theory of cryptography’. In 1948 he published some of his work in the open literature, and the 1945 article, declassified, was published soon after. With additional material by Warren Weaver, it appeared in 1949 as The Mathematical Theory of Communication.

Shannon wanted to know how to transmit messages effectively when the transmission channel was subject to random errors, ‘noise’ in the engineering jargon. All practical communications suffer from noise, be it from faulty equipment, cosmic rays, or unavoidable variability in circuit components. One solution is to reduce the noise by building better equipment, if possible. An alternative is to encode the signals using mathematical procedures that can detect errors, and even put them right.

The simplest error-detecting code is to send the same message twice. If you receive

the same massage twice

the same message twice

then there is clearly an error in the third word, but without understanding English it is not obvious which version is correct. A third repetition would decide the matter by majority vote and become an error-correcting code. How effective or accurate such codes are depends on the likelihood, and nature, of the errors. If the communication channel is very noisy, for instance, then all three versions of the message might be so badly garbled that it would be impossible to reconstruct it.

In practice mere repetition is too simple-minded: there are more efficient ways to encode messages to reveal or correct errors. Shannon’s starting point was to pinpoint the meaning of efficiency. All such codes replace the original message by a longer one. The two codes above double or treble the length. Longer messages take more time to send, cost more, occupy more memory, and clog the communication channel. So the efficiency, for a given rate of error detection or correction, can be quantified as the ratio of the length of the coded message to that of the original.

The main issue, for Shannon, was to determine the inherent limitations of such codes. Suppose an engineer had devised a new code. Was there some way to decide whether it was about as good as they get, or might some improvement be possible? Shannon began by quantifying how much information a message contains. By so doing, he turned ‘information’ from a vague metaphor into a scientific concept.

There are two distinct ways to represent a number. It can be defined by a sequence of symbols, for example its decimal digits, or it can correspond to some physical quantity, such as the length of a stick or the voltage in a wire. Representations of the first kind are digital, the second are analogue. In the 1930s, scientific and engineering calculations were often performed using analogue computers, because at the time these were easier to design and build. Simple electronic circuits can add or multiply two voltages, for example. However, machines of this type lacked precision, and digital computers began to appear. It very quickly became clear that the most convenient representation of numbers was not decimal, base 10, but binary, base 2. In decimal notation there are ten symbols for digits, 0–9, and every digit multiplies ten times in value for every step it moves to the left. So 157 represents

1 × 102 + 5 × 101 + 7 × 100

Binary notation employs the same basic principle, but now there are only two digits, 0 and 1. A binary number such as 10011101 encodes, in symbolic form, the number

1 × 27 + 0 × 26 + 0 × 25 + 1 × 24 + 1 × 23 + 1 × 22

+ 0 × 21 + 1 × 20

so that each digit doubles in value for every step it moves to the left. In decimal, this number equals 157 – so we have written the same number in two different forms, using two different types of notation.

Binary notation is ideal for electronic systems because it is much easier to distinguish between two possible values of a current, or a voltage, or a magnetic field, than it is to distinguish between more than two. In crude terms, 0 can mean ‘no electric current’ and 1 can mean ‘some electric current’, 0 can mean ‘no magnetic field’ and 1 can mean ‘some magnetic field’, and so on. In practice engineers set a threshold value, and then 0 means ‘below threshold’ and 1 means ‘above threshold’. By keeping the actual values used for 0 and 1 far enough apart, and setting the threshold in between, there is very little danger of confusing 0 with 1. So devices based on binary notation are robust. That’s what makes them digital.

With early computers, the engineers had to struggle to keep the circuit variables within reasonable bounds, and binary made their lives much easier. Modern circuits on silicon chips are precise enough to permit other choices, such as base 3, but the design of digital computers has been based on binary notation for so long now that it generally makes sense to stick to binary, even if alternatives would work. Modern circuits are also very small and very quick. Without some such technological breakthrough in circuit manufacture, the world would have a few thousand computers, rather than billions. Thomas J. Watson, who founded IBM, once said that he didn’t think there would be a market for more than about five computers worldwide. At the time he seemed to be talking sense, because in those days the most powerful computers were about the size of a house, consumed as much electricity as a small village, and cost tens of millions of dollars. Only big government organisations, such as the United States Army, could afford one, or make enough use of it. Today a basic, out-of-date mobile phone contains more computing power than anything that was available when Watson made his remark.

The choice of binary representation for digital computers, hence also for digital messages transmitted between computers – and later between almost any two electronic gadgets on the planet – led to the basic unit of information: the bit. The name is short for ‘binary digit’, and one bit of information is one 0 or one 1. It is reasonable to define the information ‘contained in’ a sequence of binary digits to be the total number of digits in the sequence. So the 8-digit sequence 10011101 contains 8 bits of information.

Shannon realised that simple-minded bit-counting makes sense as a measure of information only if 0s and 1s are like heads and tails with a fair coin, that is, are equally likely to occur. Suppose we know that in some specific circumstances 0 occurs nine times out of ten, and 1 only once. As we read along the string of digits, we expect most digits to be 0. If that expectation is confirmed, we haven’t received much information, because this is what we expected anyway. However, if we see 1, that conveys a lot more information, because we didn’t expect that at all.

We can take advantage of this by encoding the same information more efficiently. If 0 occurs with probability 9/10 and 1 with probability 1/10, we can define a new code like this:

000→00 (use whenever possible)

00→01 (if no 000 remains)

0→10 (if no 00 remains)

1→11 (always)

What I mean here is that a message such as

00000000100010000010000001000000000

is first broken up from left to right into blocks that read 000, 00, 0, or 1. With strings of consecutive 0s, we use 000 whenever we can. If not, what’s left is either 00 or 0, followed by a 1. So here the message breaks up as

000-000-00-1-000-1-000-00-1-000-000-1-000-000-000

and the coded version becomes

00-00-01-11-00-11-00-01-11-00-00-11-11-00-00-00

The original message has 35 digits, but the encoded version has only 32. The amount of information seems to have decreased.

Sometimes the coded version might be longer: for instance, 111 turns into 111111. But that’s rare because 1 occurs only one time in ten on average. There will be quite a lot of 000s, which drop to 00. Any spare 00 changes to 01, the same length; a spare 0 increases the length by changing to 00. The upshot is that in the long run, for randomly chosen messages with the given probabilities of 0 and 1, the coded version is shorter.

My code here is very simple-minded, and a cleverer choice can shorten the message even more. One of the main questions that Shannon wanted to answer was: how efficient can codes of this general type be? If you know the list of symbols that is being used to create a message, and you also know how likely each symbol is, how much can you shorten the message by using a suitable code? His solution was an equation, defining the amount of information in terms of these probabilities.

Suppose for simplicity that the messages use only two symbols 0 and 1, but now these are like flips of a biased coin, so that 0 has probability p of occurring, and 1 has probability q = 1– p. Shannon’s analysis led him to a formula for the information content: it should be defined as

H = −p log p − q log q

where log is the logarithm to base 2.

At first sight this doesn’t seem terribly intuitive. I’ll explain how Shannon derived it in a moment, but the main thing to appreciate at this stage is how H behaves as p varies from 0 to 1, which is shown in Figure 56. The value of H increases smoothly from 0 to 1 as p rises from 0 to  , and then drops back symmetrically to 0 as p goes from

, and then drops back symmetrically to 0 as p goes from  to 1.

to 1.

Fig 56 How Shannon information H depends on p. H runs vertically and p runs horizontally.

Shannon pointed out several ‘interesting properties’ of H, so defined:

If p = 0, in which case only the symbol 1 will occur, the information H is zero. That is, if we are certain which symbol is going to be transmitted to us, receiving it conveys no information whatsoever.

If p = 0, in which case only the symbol 1 will occur, the information H is zero. That is, if we are certain which symbol is going to be transmitted to us, receiving it conveys no information whatsoever.

The same holds when p = 1. Only the symbol 0 will occur, and again we receive no information.

The same holds when p = 1. Only the symbol 0 will occur, and again we receive no information.

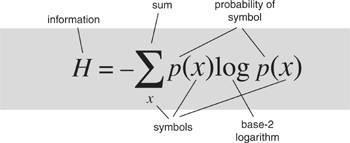

The amount of information is largest when p = q =

The amount of information is largest when p = q =  , corresponding to the toss of a fair coin. In this case,

, corresponding to the toss of a fair coin. In this case,

bearing in mind that the logarithms are to base 2. That is, one toss of a fair coin conveys one bit of information, as we were originally assuming before we started worrying about coding messages to compress them, and biased coins.

In all other cases, receiving one symbol conveys less information than one bit.

In all other cases, receiving one symbol conveys less information than one bit.

The more biased the coin becomes, the less information the result of one toss conveys.

The more biased the coin becomes, the less information the result of one toss conveys.

The formula treats the two symbols in exactly the same way. If we exchange p and q, then H stays the same.

The formula treats the two symbols in exactly the same way. If we exchange p and q, then H stays the same.

All of these properties correspond to our intuitive sense of how much information we receive when we are told the result of a coin toss. That makes the formula a reasonable working definition. Shannon then provided a solid foundation for his definition by listing several basic principles that any measure of information content ought to obey and deriving a unique formula that satisfied them. His set-up was very general: the message could choose from a number of different symbols, occurring with probabilities p1, p2, …, pn where n is the number of symbols. The information H conveyed by a choice of one of these symbols should satisfy:

H is a continuous function of p1, p2, …, pn. That is, small changes in the probabilities should lead to small changes in the amount of information.

H is a continuous function of p1, p2, …, pn. That is, small changes in the probabilities should lead to small changes in the amount of information.

If all of the probabilities are equal, which implies they are all 1/n, then H should increase if n gets larger. That is, if you are choosing between 3 symbols, all equally likely, then the information you receive should be more than if the choice were between just 2 equally likely symbols; a choice between 4 symbols should convey more information than a choice between 3 symbols, and so on.

If all of the probabilities are equal, which implies they are all 1/n, then H should increase if n gets larger. That is, if you are choosing between 3 symbols, all equally likely, then the information you receive should be more than if the choice were between just 2 equally likely symbols; a choice between 4 symbols should convey more information than a choice between 3 symbols, and so on.

If there is a natural way to break a choice down into two successive choices, then the original H should be a simple combination of the new Hs.

If there is a natural way to break a choice down into two successive choices, then the original H should be a simple combination of the new Hs.

This final condition is most easily understood using an example, and I’ve put one in the Notes.1 Shannon proved that the only function H that obeys his three principles is

or a constant multiple of this expression, which basically just changes the unit of information, like changing from feet to metres.

There is a good reason to take the constant to be 1, and I’ll illustrate it in one simple case. Think of the four binary strings 00, 01, 10, 11 as symbols in their own right. If 0 and 1 are equally likely, each string has the same probability, namely  . The amount of information conveyed by one choice a such a string is therefore

. The amount of information conveyed by one choice a such a string is therefore

That is, 2 bits. Which is a sensible number for the information in a length-2 binary string when the choices 0 and 1 are equally likely. In the same way, if the symbols are all length-n binary strings, and we set the constant to 1, then the information content is n bits. Notice that when n = 2 we obtain the formula pictured in Figure 56. The proof of Shannon’s theorem is too complicated to give here, but it shows that if you accept Shannon’s three conditions then there is a single natural way to quantify information.2 The equation itself is merely a definition: what counts is how it performs in practice.

Shannon used his equation to prove that there is a fundamental limit on how much information a communication channel can convey. Suppose that you are transmitting a digital signal along a phone line, whose capacity to carry a message is at most C bits per second. This capacity is determined by the number of binary digits that the phone line can transmit, and it is not related to the probabilities of various signals. Suppose that the message is being generated from symbols with information content H, also measured in bits per second. Shannon’s theorem answers the question: if the channel is noisy, can the signal be encoded so that the proportion of errors is as small as we wish? The answer is that this is always possible, no matter what the noise level is, if H is less than or equal to C. It is not possible if H is greater than C. In fact, the proportion of errors cannot be reduced below the difference H—C, no matter which code is employed, but there exist codes that get as close as you wish to that error rate.

Shannon’s proof of his theorem demonstrates that codes of the required kind exist, in each of his two cases, but the proof doesn’t tell us what those codes are. An entire branch of information science, a mixture of mathematics, computing, and electronic engineering, is devoted to finding efficient codes for specific purposes. It is called coding theory. The methods for coming up with these codes are very diverse, drawing on many areas of mathematics. It is these methods that are incorporated into our electronic gadgetry, be it a smartphone or Voyager 1’s transmitter. People carry significant quantities of sophisticated abstract algebra around in their pockets, in the form of software that implements error-correcting codes for mobile phones.

I’ll try to convey the flavour of coding theory without getting too tangled in the complexities. One of the most influential concepts in the theory relates codes to multidimensional geometry. It was published by Richard Hamming in 1950 in a famous paper, ‘Error detecting and error correcting codes’. In its simplest form, it provides a comparison between strings of binary digits. Consider two such strings, say 10011101 and 10110101. Compare corresponding bits, and count how many times they are different, like this:

10011101

10110101

where I’ve marked the differences in bold type. Here there are two locations at which the bit-strings differ. We call this number the Hamming distance between the two strings. It can be thought of as the smallest number of one-bit errors that can convert one string into the other. So it is closely related to the likely effect of errors, if these occur at a known average rate. That suggests it might provide some insight into how to detect such errors, and maybe even how to put them right.

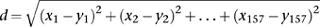

Multidimensional geometry comes into play because the strings of a fixed length can be associated with the vertices of a multidimensional ‘hypercube’. Riemann taught us how to think of such spaces by thinking of lists of numbers. For example, a space of four dimensions consists of all possible lists of four numbers: (x1, x2, x3, x4). Each such list is considered to represent a point in the space, and all possible lists can in principle occur. The separate xs are the coordinates of the point. If the space has 157 dimensions, you have to use lists of 157 numbers: (x1, x2,…, x157). It is often useful to specify how far apart two such lists are. In ‘flat’ Euclidean geometry this is done using a simple generalisation of Pythagoras’s theorem. Suppose we have a second point (y1, y2, …, y157) in our 157-dimensional space. Then the distance between the two points is the square root of the sum of the squares of the differences between corresponding coordinates. That is,

If the space is curved, Riemann’s idea of a metric can be used instead.

Hamming’s idea is to do something very similar, but the values of the coordinates are restricted to just 0 and 1. Then (x1 – y1)2 is 0 if x1 and y1 are the same, but 1 if not, and the same goes for (x2 – y2)2 and so on. He also omitted the square root, which changes the answer, but in compensation the result is always a whole number, equal to the Hamming distance. This notion has all the properties that make ‘distance’ useful, such as being zero only when the two strings are identical, and ensuring that the length of any side of a ‘triangle’ (a set of three strings) is less than or equal to the sum of the lengths of the other two sides.

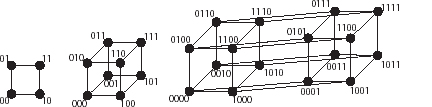

We can draw pictures of all bit strings of lengths 2, 3, and 4 (and with more effort and less clarity, 5, 6, and possibly even 10, though no one would find that useful). The resulting diagrams are shown in Figure 57.

Fig 57 Spaces of all bit-strings of lengths 2, 3, and 4.

The first two are recognisable as a square and a cube (projected on to a plane because it has to be printed on a sheet of paper). The third is a hypercube, the 4-dimensional analogue, and again this has to be projected on to a plane. The straight lines joining the dots have Hamming length 1 – the two strings at either end differ in precisely one location, one coordinate. The Hamming distance between any two strings is the number of such lines in the shortest path that connects them.

Suppose we are thinking of 3-bit strings, living on the corners of a cube. Pick one of the strings, say 101. Suppose the rate of errors is at most one bit in every three. Then this string may either be transmitted unchanged, or it could end up as any of 001, 111, or 100. Each of these differs from the original string in just one location, so its Hamming distance from the original string is 1. In a loose geometrical image, the erroneous strings lie on a ‘sphere’ centred at the correct string, of radius 1. The sphere consists of just three points, and if we were working in 157-dimensional space with a radius of 5, say, it wouldn’t even look terribly spherical. But it plays a similar role to an ordinary sphere: it has a fairly compact shape, and it contains exactly the points whose distance from the centre is less than or equal to the radius.

Suppose we use the spheres to construct a code, so that each sphere corresponds to a new symbol, and that symbol is encoded with the coordinates of the centre of the sphere. Suppose moreover that these spheres don’t overlap. For instance, I might introduce a symbol a for the sphere centred at 101. This sphere contains four strings: 101, 001, 111, and 100. If I receive any of these four strings, I know that the symbol was originally a. At least, that’s true provided my other symbols correspond in a similar way to spheres that do not have any points in common with this one.

Now the geometry starts to make itself useful. In the cube, there are eight points (strings) and each sphere contains four of them. If I try to fit spheres into the cube, without them overlapping, the best I can manage is two of them, because 8/4 = 2. I can actually find another one, namely the sphere centred on 010. This contains 010, 110, 000, 011, none of which are in the first sphere. So I can introduce a second symbol b associated with this sphere. My error-correcting code for messages written with a and b symbols now replaces every a by 101, and every b by 010. If I receive, say,

101-010-100-101-000

then I can decode the original message as

a-b-a-a-b

despite the errors in the third and fifth string. I just see which of my two spheres the erroneous string belongs to.

All very well, but this multiplies the length of the message by 3, and we already know an easier way to achieve the same result: repeat the message three times. But the same idea takes on a new significance if we work in higher-dimensional spaces. With strings of length 4, the hypercube, there are 16 strings, and each sphere contains 5 points. So it might be possible to fit three spheres in without them overlapping. If you try that, it’s not actually possible – two fit in but the remaining gap is the wrong shape. But the numbers increasingly work in our favour. The space of strings of length 5 contains 32 strings, and each sphere uses just 6 of them – possibly room for 5, and if not, a better chance of fitting in 4. Length 6 gives us 64 points, and spheres that use 7, so up to 9 spheres might fit in.

From this point on a lot of fiddly detail is needed to work out just what is possible, and it helps to develop more sophisticated methods. But what we are looking at is the analogue, in the space of strings, of the most efficient ways to pack spheres together. And this is a long-standing area of mathematics, about which quite a lot is known. Some of that technique can be transferred from Euclidean geometry to Hamming distances, and when that doesn’t work we can invent new methods more suited to the geometry of strings. As an example, Hamming invented a new code, more efficient than any known at the time, which encodes 4-bit strings by converting them into 7-bit strings. It can detect and correct any single-bit error. Modified to an 8-bit code, it can detect, but not correct, any 2-bit error.

This code is called the Hamming code. I won’t describe it, but let’s do the sums to see if it might be possible. There are 16 strings of length 4, and 128 of length 7. Spheres of radius 1 in the 7-dimensional hypercube contain 8 points. And 128/8 = 16. So with enough cunning, it might just be possible to squeeze the required 16 spheres into the 7-dimensional hypercube. They would have to fit exactly, because there’s no spare room left over. As it happens, such an arrangement exists, and Hamming found it. Without the multidimensional geometry to help, it would be difficult to guess that it existed, let alone find it. Possible, but hard. Even with the geometry, it’s not obvious.

Shannon’s concept of information provides limits on how efficient codes can be. Coding theory does the other half of the job: finding codes that are as efficient as possible. The most important tools here come from abstract algebra. This is the study of mathematical structures that share the basic arithmetical features of integers or real numbers, but differ from them in significant ways. In arithmetic, we can add numbers, subtract them, and multiply them, to get numbers of the same kind. For the real numbers we can also divide by anything other than zero to get a real number. This is not possible for the integers, because, for example,  is not an integer. However, it is possible if we pass to the larger system of rational numbers, fractions. In the familiar number systems, various algebraic laws hold, for example the commutative law of addition, which states that 2 + 3 = 3 + 2 and the same goes for any two numbers.

is not an integer. However, it is possible if we pass to the larger system of rational numbers, fractions. In the familiar number systems, various algebraic laws hold, for example the commutative law of addition, which states that 2 + 3 = 3 + 2 and the same goes for any two numbers.

The familiar systems share these algebraic properties with less familiar ones. The simplest example uses just two numbers, 0 and 1. Sums and products are defined just as for integers, with one exception: we insist that 1 + 1 = 0, not 2. Despite this modification, all of the usual laws of algebra survive. This system has only two ‘elements’, two number-like objects. There is exactly one such system whenever the number of elements is a power of any prime number: 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13, 16, and so on. Such systems are called Galois fields after the French mathematician Évariste Galois, who classified them around 1830. Because they have finitely many elements, they are suited to digital communications, and powers of 2 are especially convenient because of binary notation.

Galois fields lead to coding systems called Reed–Solomon codes, after Irving Reed and Gustave Solomon who invented them in 1960. They are used in consumer electronics, especially CDs and DVDs. They are error-correcting codes based on algebraic properties of polynomials, whose coefficients are taken from a Galois field. The signal being encoded – audio or video – is used to construct a polynomial. If the polynomial has degree n, that is, the highest power occurring is xn, then the polynomial can be reconstructed from its values at any n points. If we specify the values at more than n points, we can lose or modify some of the values without losing track of which polynomial it is. If the number of errors is not too large, it is still possible to work out which polynomial it is, and decode to get the original data.

In practice the signal is represented as a series of blocks of binary digits. A popular choice uses 255 bytes (8-bit strings) per block. Of these, 223 bytes encode the signal, while the remaining 32 bytes are ‘parity symbols’, telling us whether various combinations of digits in the uncorrupted data are odd or even. This particular Reed–Solomon code can correct up to 16 errors per block, an error rate just less than 1%.

Whenever you drive along a bumpy road with a CD on the car stereo, you are using abstract algebra, in the form of a Reed–Solomon code, to ensure that the music comes over crisp and clear, instead of being jerky and crackly, perhaps with some parts missing altogether. Information theory is widely used in cryptography and cryptanalysis – secret codes and methods for breaking them. Shannon himself used it to estimate the amount of coded messages that must be intercepted to stand a chance of breaking the code. Keeping information secret turns out to be more difficult than might be expected, and information theory sheds light on this problem, both from the point of view of the people who want it kept secret and those who want to find out what it is. This issue is important not just to the military, but to everyone who uses the Internet to buy goods or engages in telephone banking.

Information theory now plays a significant role in biology, particularly in the analysis of DNA sequence data. The DNA molecule is a double-helix, formed by two strands that wind round each other. Each strand is a sequence of bases, special molecules that come in four types – adenine, guanine, thymine, and cytosine. So DNA is like a code message written using four possible symbols: A, G, T, and C. The human genome, for example, is 3 billion bases long. Biologists can now find the DNA sequences of innumerable organisms at a rapidly growing rate, leading to a new area of computer science: bioinformatics. This centres on methods for handling biological data efficiently and effectively, and one of its basic tools is information theory.

A more difficult issue is the quality of information, rather than the quantity. The messages ‘two plus two make four’ and ‘two plus two make five’ contain exactly the same amount of information, but one is true and the other is false. Paeans of praise for the information age ignore the uncomfortable truth that much of the information rattling around the Internet is misinformation. There are websites run by criminals who want to steal your money, or denialists who want to replace solid science by whichever bee happens to be buzzing around inside their own bonnet.

The vital concept here is not information as such, but meaning. Three billion DNA bases of human DNA information are, literally, meaningless unless we can find out how they affect our bodies and behaviour. On the tenth anniversary of the completion of the Human Genome Project, several leading scientific journals surveyed medical progress resulting so far from listing human DNA bases. The overall tone was muted: a few new cures for diseases have been found so far, but not in the quantity originally predicted. Extracting meaning from DNA information is proving harder than most biologists had hoped. The Human Genome Project was a necessary first step, but it has revealed just how difficult such problems are, rather than solving them.

The notion of information has escaped from electronic engineering and invaded many other areas of science, both as a metaphor and as a technical concept. The formula for information looks very like that for entropy in Boltzmann’s approach to thermodynamics; the main differences are logarithms to base 2 instead of natural logarithms, and a change in sign. This similarity can be formalised, and entropy can be interpreted as ‘missing information’. So the entropy of a gas increases because we lose track of exactly where its molecules are, and how fast they’re moving. The relation between entropy and information has to be set up rather carefully: although the formulas are very similar, the context in which they apply is different. Thermodynamic entropy is a large-scale property of the state of a gas, but information is a property of a signal-producing source, not of a signal as such. In 1957 the American physicist Edwin Jaynes, an expert in statistical mechanics, summed up the relationship: thermodynamic entropy can be viewed as an application of Shannon information, but entropy itself should not be identified with missing information without specifying the right context. If this distinction is borne in mind, there are valid contexts in which entropy can be viewed as a loss of information. Just as entropy increase places constraints on the efficiency of steam engines, the entropic interpretation of information places constraints on the efficiency of computations. For example, it must take at least 5.8 × 10-23 joules of energy to flip a bit from 0 to 1 or vice versa at the temperature of liquid helium, whatever method you use.

Problems arise when the words ‘information’ and ‘entropy’ are used in a more metaphorical sense. Biologists often say that DNA determines ‘the information’ required to make an organism. There is a sense in which this is almost correct: delete ‘the’. However, the metaphorical interpretation of information suggests that once you know the DNA, then you know everything there is to know about the organism. After all, you’ve got the information, right? And for a time many biologists thought that this statement was close to the truth. However, we now know that it is overoptimistic. Even if the information in DNA really did specify the organism uniquely, you would still need to work out how it grows and what the DNA actually does. However, it takes a lot more than a list of DNA codes to create an organism: so-called epigenetic factors must also be taken into account. These include chemical ‘switches’ that make a segment of DNA code active or inactive, but also entirely different factors that are transmitted from parent to offspring. For human beings, those factors include the culture in which we grow up. So it pays not to be too casual when you use technical terms like ‘information’.