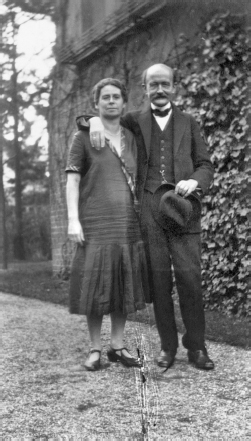

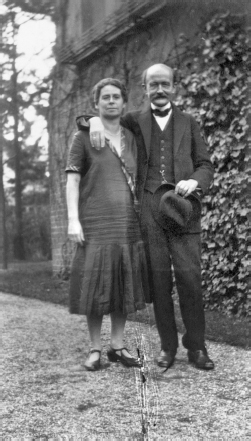

Figure 8.1 Marga and Max Planck in Grunewald, 1924.

Courtesy Archiv der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Berlin-Dahlem.

Max had two dear granddaughters—one by each of his twin daughters—and he helped raise them from infancy. Grete Marie (daughter of Grete) and Emmerle (daughter of Emma), both grew up in Germany’s lean, chaotic interwar years. When Hitler came to power in 1933, Grete was 15 and Emmerle was 13. During World War II, Emmerle apprenticed as a nurse-in-training in the small city of Erfurt. She assisted with the floods of wounded soldiers and the growing ranks of civilians maimed or burned by Allied bombing.

In mid-spring of 1944, Emmerle climbed to a third-story window in Erfurt and threw herself into the air.1 We do not know what placed her, at age 24, on that emotional edge. Max, the grandfather, blamed it on the “unstable” nature of Emmerle’s father, Planck’s son-in-law Ferdinand Fehling.2 The ever-growing ranks of wounded, and the certainty of defeat, could not have helped. She survived the three-story fall but cracked a number of vertebrae, and she recovered in a local hospital, receiving care she’d sought to deliver.

Such attempts were increasingly common in Germany and culminated in a wave of mass suicides at the war’s end.3 The sad trend began after World War I, and despite Nazi propaganda claiming to have solved the problem, suicides continued at a disturbing clip from 1933 to 1939, when official statistics become alternately unavailable or unreliable. Some suicides were driven by fear of the Reich, especially when citizens were accused of racial impurity, homosexuality, refusal to work, or immoral behavior. As German war fortunes stumbled in 1942 and as the Allies began heavy bombardment, depression and suicides naturally increased. In fact, Emmerle’s attempt occurred within a string that followed the massive bombing of Frankfurt that March.4

Despite his own increasing physical anguish, Max and Marga went immediately to Emmerle’s side during her recuperation. Marga figures in Planck’s tragedy as a fixture of bedrock in the personal quicksand surrounding them. She married her uncle Max and provided steadfast support throughout the most trying years of his life. She greatly enjoyed entertaining, supporting the Geheimrat (i.e., most respected, or “esteemed”) Professor Planck’s demanding social calendar and facilitating his work. She even accompanied him step for step on some of his challenging alpine climbs. The two of them could put a 20-something’s spry youth to shame, as reported by their neighbor’s son Axel von Harnack. He recalled one alpine hike from the years of World War I.

During the ascent Planck did not speak a word nor did he rest even for a moment. He, a man of almost sixty, was decidedly superior to me, the young student, in his endurance and toughness. The first brief break was made after four hours ascent. We took a very modest war meal, then went on over four further mountain tops which made significant claims on our strength. A very brief rest on the summit, and down we went again. When we came home in the late afternoon, the Planck couple was surprisingly fresh, while I was at the end of my tether. Through-out the march Planck spoke very little, but his features revealed his great joy about the wonderful scenery around us.5

Max had known Marga for many years before their marriage, perhaps even in her childhood. She was born in Munich and would have been five years old—a ring-bearer’s age—if she attended Max and Marie’s wedding there. The decision to remarry has the whiff of Max Planck’s pragmatism: He maintained his ties to the Merck/von Hoesslin family, including fond trips to see them in the German Alps; he quickly filled the critical vacancy of faculty wife; he recruited a hostess and mother figure for the household; and he secured a younger partner, both hale and willing as he approached the later stages of life (Figure 8.1). After his death, she wrote that it was an honor to have lived with and assisted such an august man.6

Figure 8.1 Marga and Max Planck in Grunewald, 1924.

Courtesy Archiv der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Berlin-Dahlem.

After Marga joined the household, she conceived at once, and on Christmas Eve, 1911, she gave birth to Hermann Wilhelm Heinrich Planck, their only child together. Max was overjoyed, and the family took to calling Hermann “Bubie.” It was a special delight, for instance, when Bubie, presumably in Marga’s arms, brought his father a daisy on April 23, 1912, Max’s fifty-fourth birthday.7

To take stock, we pause in 1912. Max had lost Marie, but he was by no means lonely. He had already married again and found himself surrounded by five healthy children (spanning Hermann in infancy to Karl at age 24). He also had two other remarkable women in his life: his mother Emma and Lise Meitner. His discovery of 1900 was, at long last, attracting more attention and discussion; he had just bathed in the stimulation of the first scientific meeting geared to discuss the new quantum theory—the first Solvay conference in Brussels—and he was but one year from seeing the Danish physicist Niels Bohr take the original quantum hypothesis and revolutionize the very notion of matter itself. In 1912, the Prussian Academy of Sciences elected Max (unanimously but for one anonymous vote), to the prestigious Secretary position. His neighbor Adolf von Harnack had spearheaded the formation of a new research organization, the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, devised to enable grand scientific work that was too expensive for individual universities. And Planck was already scheming to bring Albert Einstein to Berlin, placing the crown jewel atop German science and securing its international standing for, he must have assumed, decades to come.

But worries simmered within the family. The depression that would push his granddaughter Emmerle from a window in 1944 must have been familiar to Planck. Max’s daughter Grete had been briefly institutionalized with a “nervous attack” at an eerily similar age, around her twenty-fourth birthday in 1913. After two weeks in a sanatorium, she reportedly emerged with changed perspective and a focused life plan.8

But the most serious case of emotional torment played across the brief life of Karl Planck, Max and Marie’s eldest child. As a young man adrift with no particular drive or discipline, he faced great tension with his father, a man with nearly inhuman focus. “My eldest, Karl, who was originally becoming a lawyer,” Planck relayed to the letter diary in 1908, “is changing seats and has become a geographer—a worrisome jump.” Max tried to talk some sense into his son, but it was “of course, not pleasant.”9 When Karl lost his interest in geography and sought to switch his focus to art history, Erwin stood up for his older brother against their doubtful father, to no avail. The art-sympathetic Karl was a piece of whimsical kinetic sculpture compared with Max, who worked like one of the humming machines driving Germany’s industrial economy.

Karl soon lost his connection to sleep, and he struggled to make himself eat. “My brother Karl has had a nervous breakdown,” Erwin wrote to a friend in early 1912. Max committed Karl to a mental hospital in Kassel, again at an onset age of 24. Erwin went to stay with Karl over an Easter vacation, and the family soon saw improvement. But after leaving in May, Karl continued to struggle. The arguments with his father rose like regular thunderclouds, casting shadows across Planck family gatherings. In early 1913, Max wrote to Erwin that, “Karl gives me great grief again.”10

As Max delivered his first talk as the University of Berlin’s rector, in the fall of 1913, he cautioned against the lack of focus he saw in Germany’s youth. He held up the energy of America as a worthy example to them. This was nearly a personal comment, because in those days Karl still struggled. He shuffled from one job to the next without success, short-circuited by a nervous depression.11

The war interrupted Planck’s years of worry for Karl in 1914, and it appeared to many Germans as a blessed solution for all the empire’s ailments. The war brought purpose. As Erwin headed to the Western front as an officer, Karl enrolled in artillery school, and the twins volunteered as nursing assistants in various hospitals.12

The entire previous year had seen a fever pitch of nationalism as Germany loudly celebrated the 100th anniversary of chasing Napoleon Bonaparte back to France; the Empire celebrated its rising power and ambitions as well. Unlike most Germans (even German academics), Max kept a very calm tone throughout the frothing of 1913. As a newly appointed rector, many expected Planck to sound more patriotic. As festivities began in 1913, Planck noted that the professors of 1813 had, “proved their patriotism in their own way, through calm and true fulfillment of duty, just as much as the young soldiers who fought in the field for the liberation of the fatherland.”13

When the war arrived to a giddy continent, he delivered his second rector’s address to the university on August 1, 1914. He knew that his own sons and those of his colleagues would be headed to battle. He knew his lecture seats and the university’s hallways would soon be emptied of students. His remarks were incredibly prescient.

“We do not know what tomorrow will bring; we only suspect that something great, along with something monstrous, will soon confront our people, that it will touch the life and property, the honor and perhaps the existence of the nation.” Planck’s standard modus operandi in speaking and writing involved painting oppositions—in reading Planck, one starts to anticipate the next “however.” In this address, it was much more than a tic or habit. If Friedrich Nietzsche had given Germany the notion of “will to power,” Max explored a will to optimism. He felt himself pulled to the fervor of the moment as he continued that 1914 address. “But we also see and feel how, in the fearful seriousness of the situation, everything that the country could call its own in physical and moral power came together with the speed of lightning and ignited a flame of holy wrath blazing to the heavens, while so much that had been considered important and desirable fell to the side, unnoticed, as worthless frippery.”14 And he told his students, as they prepared for war, “Germany has drawn its sword against the breeding ground of insidious perfidy.”15 No one complained about a lack of patriotism this time.

He echoed these sentiments in letters. In the following month, Planck wrote to a relative that, “it is a great feeling to be able to call oneself German.” He particularly craved the unity that war brought, and he welcomed stripping away the trivial concerns and politics with which people normally wasted their days. As he wrote to friend Willy Wien a few months later, despite the admitted horrors of the conflict, “there is also much that is unexpectedly great and beautiful: the smooth solution of the most difficult domestic political questions by the unification of all parties.”16

In a book that greatly exceeds its own provocative title, Peter Englund’s The Beauty and the Sorrow presents a series of journal entries from those living in the midst of World War I. The exaltation resonating throughout the German Empire is difficult to understand with just a century’s remove. A German schoolgirl reports her headmaster overcome by tears of joy with the announcement of war. The schools quickly banned common non-German words, such as “mama” and “adieu.” And with each announcement of a battle victory, the children were allowed to scream in class, the louder and longer the better.

Train stations all over the Empire hosted celebrations. Row upon row of marching grey uniforms synced pounding boots and beating drums. Marching bands would strike up every crowd’s favorite, Die Wacht am Rein, the Watch on the Rhine, and the assembled would sing at full throat.

Dear fatherland, put your mind at rest.

Fast stands, and true, the Watch, the Watch on the Rhine.

Happy soldiers waved from train cars before departing, with “garlands of flowers around their necks or pinned on their breasts. Asters, stocks and roses stuck out of the rifle barrels.”17 Promises of soldiers could be heard over the steam engines: We’ll be home before Christmas. The journal of one French soldier encapsulates the feeling of so many then, whatever their nationality. “How humiliating it would be not to get to experience the greatest adventure of my generation!”18 This spirit swept Karl and Erwin Planck smiling into uniform, with a proud father looking on.

The overwhelming majority of German intellectuals, Planck included, stepped forward in mind, heart, and rhetoric. Most scientists agreed with what Adolf von Harnack had told Kaiser Wilhelm: “Military power and science are the twin pillars of Germany’s greatness.”19 Albert Einstein however, thought himself surrounded by madness. After Planck’s aggressive recruiting, Einstein had just started his new post in Berlin in 1913, only to be reminded of the rampant militarism of his Munich childhood. He subscribed to a politics much more liberal than Planck’s, aligning himself with the ultraprogressive New German League, a party banned by the Kaiser’s government. Weeks after the outbreak of hostilities, Einstein wrote to his friend Paul Ehrenfest that mankind was “a sorry species” if it could celebrate war.20 Later he wrote, “that a man can take pleasure in marching in fours to the strains of a band is enough to make me despise him … [and he] has only been given his big brain by mistake; unprotected spinal marrow was all he needed.”21

Lise Meitner’s view was more typical of academics at the time, as she supported the war, particularly as a native Austrian. She wrote to her colleague Otto Hahn about a night of entertainment and conversation at the Plancks in 1916. “They played two gorgeous trios, Schubert and Beethoven. Einstein played violin and on the other side volunteered some naïve and strange opinions about politics and war. Just the fact that there is an educated person around who in this time does not touch any newspapers is certainly curious.”22 And this was presumably Planck’s view of Einstein as well: The wacky politics were just a curious side effect of such genius, drifting in thoughts of outer space (and time).

Another of Planck’s colleagues frames the other end of the academic spectrum. The great chemist Walther Nernst lost two sons in the first 18 months of the war, but proudly so. He volunteered to drive an ambulance at the front, and he could be spotted, in uniform, practicing his high-step in the front lawn while asking his wife to critique his form.23 This was a not-so-unusual example of delirious commitment to World War I in its first stages.

The singing in the streets of Munich escorted Max’s mother, Emma, from life on August 4, shortly after his rector’s address in Berlin. His lifelong close friend died at 93, vigorous and lively into her later months. He was unable to attend her funeral in Munich because war mobilization trumped civilian rail travel.24

Despite losing the two women dearest to him within five years, he remained bullish on the future of the family, the empire, and physics. His sons pursued honor, the Kaiser was righteous, and German physics promised years of dominant progress with Einstein at the lead. One wonders if Planck ever regarded his own sorrow at losing mother Emma and wife Marie as “frippery” when compared with the great uniting mission confronting the empire.

The war started with a steady stream of German victories. While most Germans assumed Russia was the primary enemy and that all trains should be hauling soldiers to the east, military advisors had persuaded the Kaiser to quickly neuter France, a primary Russian ally. And given Germany’s last success against France, in 1870, most military leaders thought it a sane strategy. As some crowds looked on in confusion, a number of military trains headed west. With Erwin Planck in their midst, the first German units marched quickly through Belgium and into France, pushing French units into full retreat. This new conflict began to look as easy as the Franco-Prussian War, but the success only lasted a few weeks.

The more sober reality hit home by October, when the first battle of Ypres killed 40,000 German soldiers in 20 days—at home, citizens called it the Kindermord, or “the children’s slaughter.” In a single battle, Germany suffered twice the losses it had in the entire Franco-Prussian War. A German schoolgirl wrote in her diary about helping the Red Cross feed departing and returning soldiers. On a biting December night, with snowflakes drifting through the light of gas lamps, they made hundreds of onion sausage sandwiches and carried vats of pea soup to the troops. She noted the sharp difference in the trains. For everyone departing with eager and singing soldiers, another would come back, full of silent and damaged men.25

What would Erwin or Karl have experienced on their way to battle? If they were among the lucky, they shipped in a train with windows, though many German soldiers moved hundreds of miles shaking to and fro in darkened cattle cars. Transit could take as long as four days. Detraining, they would walk the last miles toward the front. Soldiers reported seeing the orange muzzle flashes from a great distance, looking nervously at the jagged, angry horizon, and then approaching an ever-louder realm, drained of color and shredded by artillery. One young soldier deployed near Liege wrote in his journal, “Where there had once been tall white houses with shutters on their windows, nothing remains but spiky, rain-blackened heaps of rubble, bricks, and splintered wood. The projectiles from shrapnel shells and shell fragments lie scattered all over the streets. The little town is slowly being ground down into the earth.”26

By Christmas of 1914, the barrage of bad news had choked all hopes of a speedy conflict, and the extent of Europe’s mass delusion became clear. Gone were dreams of daring exploits, crushed by a new reality. The chemistry of explosives and the engineering of firearms made humans almost irrelevant. Standing men were clutter to be swept to the side in violent bursts. There was no longer a good soldier or a weak soldier—just lucky or unlucky ones. As of December of 1914, the surreal networks of trenches were already set and spreading rapidly as long stretches of barbed wire unfurled across the ravaged landscapes. Though frequently cold, muddy, and miserable, German soldiers and officers helped themselves to French interiors. “Shelters in the trenches are cheaply and gaudily furnished with loot from French homes,” wrote the same soldier near Liege. “Everything from woodstoves and soft beds to household equipment and beautiful sofas and chairs.” Eventually, some trenches put up electric lighting, and even wainscoting.27

Karl Planck would have seen these incongruous details from a distance: Such comforts were typically reserved for officers. Karl would have turned to his own gear for respite. A German soldier’s standard kit list from 1914 included, for example: one aluminum mug, gray gloves, two tins of coffee, one tin of rifle grease, two bandages, two pairs of underwear, four pairs of socks, knee warmers, a white armband for night fighting, one speckwurst sausage, the New Testament, 30 field postcards, and anise oil (as an antiseptic).28 Though the standard kit also included 150 rounds of ammunition, most soldiers like Karl fired very few shots.

Life in the trenches involved a lot of boredom. Days or weeks could pass in relative silence, with the men writing postcards, digging trenches into the night, or eventually playing pranks on one another, such as putting pepper in one another’s gas masks, or “pig snouts,” as the German soldiers called them. Gunfire and shelling could start up at random, or from something as senseless as a soldier shooting at a bird. Several dead bodies later, silence would return with just as little explanation.

German soldiers reported the hunger of French citizens around them. One wrote of the horrible waste perpetrated, as soldiers spread oats on cobblestones to muffle the movement of artillery pieces, all while hungry civilians looked on.29 The most severe food shortages were in Germany and Austria. Conscription of farmers and even farm horses into the military greatly hurt domestic food production, and the British dominance of the northern seas effectively cut Germany off from food imports. As early as January 1915, newspapers carried warnings like the following: “Any individual using corn as animal fodder is committing a sin against the Fatherland and may be punished.” By 1917, the average German had lost 20% of his or her prewar weight.30

As of March 1915, two of Max Planck’s nephews had been killed in the fighting, and Carl Runge’s son Bernhard died in the Kindermord in 1914.31 “Where is the compensation for all this unspeakable suffering?” Planck wrote to the beloved Dutch physicist Hendrik Lorentz.32 And Max suffered daily on account of Erwin.

In September of 2014, Erwin went missing at the battle of the Marne, Germany’s first setback. After miserable weeks looking for answers, Max and Marga learned that he was wounded but alive as a prisoner in France. In time, they were allowed to exchange letters, as long as they wrote in Latin. “Thank god he at least is healthy,” Planck wrote to his cousin’s family. “And has been writing with good courage in spite of bad treatment he’s receiving at St. Angeau.”33 The empire bestowed a number of medals on Erwin, including one recognizing battle wounds, and Max collected all of them.

Erwin Planck had pursued officer’s training well before the war, with financial support from his father. When he earned his Leutnantspatent in August of 1912, Max learned of it in the newspaper and sent his son a proud telegram.34 Erwin completed officer’s training in the spring of 1913, joined the military reserves, and immediately began medical school. After just a year, the war called him to duty, where his officer’s status presumably helped preserve his life as a prisoner. In the prison camp, as in the trenches, rumors constantly percolated. The war would end next year since everyone was running out of bullets. Montenegro surrendered to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, so surely the war would end within months. Et cetera.

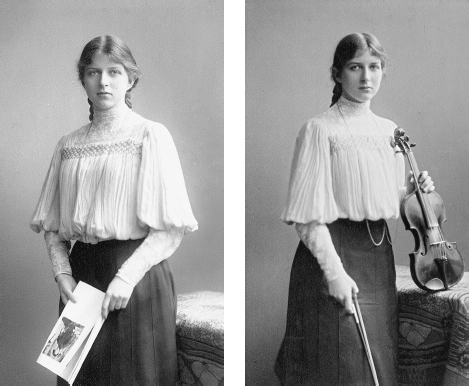

After they established regular communication with Erwin, including Max reading his letters aloud to Marga and daughter Emma, the rest of the Planck clan weathered the war’s first months in relatively good spirits. Daughter Grete had studied violin within Heidelberg’s music conservatory where she met and, in the war’s first weeks, married a middle-aged history professor named Ferdinand Fehling. Max told his friends that Grete was “war married,” as Professor Fehling joined the war effort and deployed to the northern border. Planck had not met this fellow, but at least he was of Prussian stock, born and raised in Lübeck, near Kiel.35 Given her recent struggles with depression, one can imagine Max Planck’s relief for his daughter, though he would have preferred a more traditional courtship (Figure 8.2). Emma went to meet her new brother-in-law and reported to Max that they would, “get along well … he is a very vivacious, spirited, and artistic man.”36

Figure 8.2 Grete (left) and Emma (right) Planck in 1906.

Emma herself enjoyed her early days of hospital work, referring to the wounded soldiers as “her little sheep.” She wrote to Erwin regularly, saying she missed her siblings terribly but said it was, “wonderful for me to be doing a job that is important during the war.” She led her wounded flock in singing together, and for those on the mend, even took them outside for sledding and snowball fights in the war’s first winter.37

Against all odds, worrisome Karl was thriving. His father later wrote that his son was “one of those healed by the war.”38 Emma and Max relayed to captured Erwin that Karl was better than ever, achieving a promotion to Sergeant in the summer of 1915. After his first battle wound, catching shrapnel in his shoulder, he visited the family home in November but yearned to return to the front.39 Most wounded who could still walk, talk, and use their arms had to return to the fight, and Karl was no exception.

In February 1916, the German army launched a new offensive, trying to break the will of the French near Verdun. Over the next 10 months, the intensive fighting would yield no more than 10 kilometers of progress to repay avalanches of casualties.

We can see Verdun through the diary entries of the Frenchman Rene Arnaud. As a leader of his unit, he was told, “the whole thing is very simple. You will be relieved when three-quarters of your men have been knocked out. That’s the going rate.”40 And so it was for both armies at Verdun, where the two sides matched one another casualty for casualty. In the end, the nearly three quarters of a million casualties ranks Verdun as one of the most deadly single battles in human history. If we printed the names one per line, single-spaced, we would have a 15,000-page book with a binding six-feet thick. Severely wounded in May, Karl Planck drifted from life amid this heap.

Planck wrote to his cousin’s family that they could not confirm his death “with absolute certainty” but knew it must have been true given “intense” injuries. “My dearest wish is that he didn’t suffer any more. The pain of this war you only feel for real when you feel it in your own flesh and blood. There were times where I was not without sorrow for Karl’s future. Then his life didn’t seem so precious to me as it’s been presented to me now.” Ever mindful of his audience and of his cousin’s own concerns, he returns to patriotism, despite the absurdity of the battle, the meaninglessness of another useless, pulverized fort, and its human price. “We did not know that Fritz is stationed near Verdun. I hope that he will help seize it. This would be a great step forward.”41

Before the war, Max had prepared himself for years of suffering with Karl, as his troubles appeared beyond resolution. The war provided a perverse hope for a life of meaning and then it severed any long-term concern. “Without the war I never would have known his value,” Planck later wrote to Willy Wien. “And now that I know it, I must lose him.”42

Meanwhile, Planck was busy keeping German science inching forward with less funding and fewer pairs of hands for laboratories and notebooks. In 1916, the Kaiser himself appointed Max as senator to the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, overseeing and promoting the empire’s scientific enterprise. Planck’s friend and colleague Einstein deeply imbedded himself in what he called the greatest idea of his life. Against Planck’s advice, he spent most of the war year’s refining a bold rewrite of Newton’s gravity. And Lise Meitner threw herself further into radioactivity research, despite Otto Hahn being called to serve in the war. Before the war, she had already expressed misgivings about her tunnel vision, and these echo the feelings of many scientists, both in and out of wartime. As she wrote to a friend, “what distresses me most is the frightful egotism of my current way of life. Everything I do benefits only me, my ambition and my pleasure in scientific work. It seems I have chosen a path which flies in the face of my most deeply held principle, that everyone should be there for others.”43 Although Meitner penned this shortly after her father’s death, such sentiments could not have waned during the war’s devastation.

By the end of 1916, the Central Powers offered peace to the Entente, but the overture was quickly rejected. Though not yet at war, the American president Woodrow Wilson spoke with a firm voice against the offer, saying that without more specifics, such overtures were meaningless.44 The war lurched forward. As of Christmas 1916, Planck had lost his oldest child, while another child concluded his second year in a prison camp. The only sparkle of positive news came from Grete: She was pregnant, headed for a springtime birth and a new generation. While it was a difficult time to start a family, Planck the optimist welcomed the news.

But an early 1916 frost cut the German potato crop in half, and the German Empire entered its infamous “turnip winter.” With the British naval blockade squeezing the German food supply harder than ever, the nation’s overreliance on homegrown potatoes left no room for error. Even before the war, the average German ate nearly 1,300 pounds of potatoes per year.45 The failure of the potato crops in 1916 left a disastrous void in German pots and stomachs. Turnips provided the only available substitute, and they became known as “Prussian Pineapples.” Families faced mashed turnips, turnip soup, and turnip salad. Those seeking variety tried turnip pudding and turnip balls with turnip jam.46 Disease flourished among the malnourished and ever-hungry civilian population. Planck himself, famously never ill, was bedridden in December of 1916 with a bronchitis bordering on pneumonia.47

In 1917, approaching a thirty-eighth birthday, Einstein developed a debilitating stomach ailment. Poor nutrition exacerbated or even caused his suffering, but his personal life couldn’t have helped. Separated since his move to Berlin, he and his wife Mileva Maric now discussed divorce. He once wondered aloud to her which would conclude first, the war or their divorce process, and in fact, the armistice of World War I preceded the divorce by a number of months.48 Whatever the causes, he lost a dramatic 50 pounds in 1917 and a great deal of energy in the bargain. And so began his famous penumbra of graying hair.

The desolate nutrition also hurt first-time mothers like Grete Planck. Germany suffered an infant mortality rate of about 19% in the turnip winter.49 Mortality among women also spiked that year, rising 30% above its prewar levels.50 Grete gave birth to a healthy baby girl in May, but then a blood clot docked in her lungs, causing a major embolism. One moment, she would have been happily nursing her one-week-old baby, Grete Marie Fehling, and then the quiet would burst with sudden symptoms: elusive breaths, a violent new cough, and chest pains. She died there in Berlin, with Max Planck nearby, and the family placed her ashes in the Grunewald cemetery. Emma informed Erwin with a heart-wrenching letter. “Especially I’m thinking of you, my poor dear muse as you are far away and must now endure a second enormous anguish,” she wrote. “I cannot imagine that our good dear sister, my inseparable twin, should be here no longer. … Grete’s life had only started now and how she would have made everyone else happy with her joy, especially those who knew her so well and went through hard times with her.” She writes of a photo of all four of them, how they naturally belonged together. “Let’s stick together, my dear muse, more tightly than ever.” And she closes with sympathy for what their father has endured, losing two of them. Max also wrote to Erwin, saying, “I wish I could be by your side … to survive this blow together and support one another.” But he urged Erwin to trust in better times to come.51

Max would assume a major role in Grete Marie’s upbringing, and naturally, Aunt Emma stepped forward to help Professor Fehling as well. Emma was a striking replica of her departed sister. Anytime Emma entered his home, Fehling must have started as if visited by a beautiful ghost.

When Erwin gained his freedom and returned home in October, still hobbled by a war-wounded thigh, he found sister Emma waiting for him at the train station. And at Wangenheimstrasse, he found a profoundly changed family, with two siblings departed and a new motherless niece. He spent time with his father and sister playing music, and they traded readings from their respective journals of the last three years.52

Incredibly, Planck found a way to stay upbeat. His longtime dream of a Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for physics came into being in 1917, though it existed more in letterhead than fact, given its lack of a physical home. In a December letter to Einstein—the appointed director of the new institute—he advised his friend on a number of administrative matters and then included a cheery personal note.

May the New Year bring you full recovery from your health complaints! I hope that during the same year your sympathies for the German Party grow as well; it is ever ready for peace, despite our being in such a favorable position militarily now as never before. I am also pleased with the rapid rise in our exchange rate.

So, on the 2nd we have colloquium. Will the room be heated then, I wonder?53

What could cause this optimism, especially as America and her resources had joined the Entente in 1917? The Bolsheviks had assumed control of Russia in November, and negotiations of a ceasefire had begun in early December. The eastern front would close, leaving more resources for the main fight to the west. And the Central Powers had made progress that autumn against Italy. Indeed, a new German offensive throughout the spring of 1918 brought them to within 60 miles of Paris. (Such bursts of positive war news set Germans up for shock and disbelief at the war’s resolution.)

In 1917, the German potato crop rebounded, but overall scarcity of basic foods and supplies strangled the Central powers. In 1918, babies received boiled rice instead of milk. Peter Englund writes of fake meats made of pressed rice, stabbed with a shaft of wood, carved to resemble a bone. The Kaiser’s government recognized 837 substitutes for meat, and 511 for coffee.54

Given severe rationing and empty stomachs, the Berlin science community welcomed the excuse of celebrating Planck’s 60th birthday with a banquet that spring. Planck’s friend Einstein stepped forward as master of ceremonies, but he worried about his performance. “I’ll be happy tonight if the gods grant me the gift to speak profoundly,” he wrote to Paul Ehrenfest, “because I am very fond of Planck. And he will certainly be very pleased when he sees how much we all care for him and how highly we value his life’s work.”55 Indeed, affection and respect rained on Planck at this celebration. The general (but not unanimous, as we will see), sentiments for Planck were encapsulated by the words of physicist Max Born. “You can certainly be of a different opinion from Planck’s,” he once wrote to Einstein, “but you can only doubt his upright, honorable character if you have none yourself.”56

By July, Allied counteroffensives relentlessly pushed the German army back. By early November, the Austro-Hungarian dual monarchy was no more, and they signed an armistice with the Allies. Meanwhile, sailors in Germany’s high seas fleet were beyond the limits of their patience. In Kiel, they mutinied against officers’ orders to return to their ships. A general strike throughout Germany followed, and Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated his throne on November 9, with an official end to conflict two days later. The exhausted and malnourished citizens of Europe had little time to celebrate the war’s ending as a devastating flu pandemic swept the continent that winter, taking another two and a half million lives, or one in every hundred remaining people.57

Postwar Berlin fell to chaos. Lise wrote with worry for her family in Vienna, but a friend wrote back: “I am almost more concerned now about Berlin than Vienna.”58 Planck wrote to the letter diary that Christmas of, “the final defeat, and even worse, the inner struggle, in which the remnant forces tear at one another.”59

Rival political factions exchanged gunfire across the Spree River, bordering the University of Berlin. A group of socialist students occupied university buildings and seized the rector (not Planck at this point), along with several deans. Einstein was called to mediate because he was the one university voice that the leftist students trusted. After several tense conversations, the students relented and freed their captives. With his colleague Max Born, Einstein walked directly from the Chancellor’s office to a nearby gathering at the Reichstag, and he delivered some prepared remarks warning against the possible excesses of the far left. He called for immediate elections, to eliminate fears of a new form of dictatorship. Twenty-five years later, with Hitler in power, he looked back on this day with dismay. “Do you still remember the occasion?” he wrote to Born. “We were so naïve for men of forty.”60

Most of the physicists were less inclined to make political statements. They decided to reinstitute their colloquium series (weekly talks for hearing about the latest research findings), and Meitner described the herd of physicists ambling into the deathly cold lecture hall, most draped in their old army coats, with gunfire echoing in the streets outside.61

In the first half of 1919, the treaty of Versailles emerged, placing the punitive weight of the war squarely on Germany’s back. It aimed to ensure that the Empire would never again threaten its neighbors. As the economist John Maynard Keynes wrote at the time, “the economic consequences of peace” would be catastrophic for both Germany and all of Europe.62 Most Germans, including academics, were dumbfounded by the conditions. Planck’s colleague and Nobel laureate Emil Fischer (who had once feared allowing Lise Meitner into a chemistry laboratory), lost two sons during the war. In May 1919, he wrote to the great Swedish chemist Arrhenius that, “we are all shocked by the conditions of the new treaty, which are so cruel to Germany.”63 His death in July, following a diagnosis of intestinal cancer, was reported as a suicide in some circles.64

The only tentative bright spot for Planck involved daughter Emma, who was married on February 1, 1919, and soon carrying another grandchild. The new groom and father-to-be made for a familiar son-in-law: Professor Fehling. He had fallen for the lively ghost of his first wife as they cared for little Grete Marie together.

By August 1919, a new constitution and republic congealed from an assembly in Weimar: A liberal democracy would try to lead its depressed and skeptical population, with every family reeling from war casualties, hunger, and influenza. The new government also faced staggering war debt, and the first signs of an accelerating inflation. Printing reams of money appeared to be the only way to pay their bills.

In the postwar months, Planck continued his ascent to the forefront of German science, as a spokesman and guide. He gradually assumed the position of his former teacher, Hermann von Helmholtz, as the public face of science not just in Berlin but Germany overall.65 He presented a rare and optimistic public voice. “The main thing,” he expressed to colleagues after the Versailles announcement, “is not to lose courage and the hope that better days will come.” And in a Christmas day newspaper column, he told the public that German science would ensure that the Fatherland would remain “in the ranks of civilized nations,” despite all signs to the contrary. He saw his passionate optimism as a “necessary prerequisite” to survival, and he urged others to envision a day when the Empire was even better than it had been in early 1914.66

His standing only improved in October when the Nobel committee in Stockholm announced that Max Planck had won the delayed 1918 Physics prize, for “the services he rendered to the advancement of Physics by his discovery of energy quanta.” Simultaneously, the committee awarded the 1919 prize to another German physicist, Johannes Stark—a man increasingly adversarial to both Planck and Einstein—for his laboratory exploration of single atoms responding to electric fields. (The “Stark effect” describes how an electric source affects a nearby atom’s internal structure.) Max took part of his $1.25 million reichsmarks prize and invested in Erwin.67 His son now sought a career in diplomacy, and he was headed back to school. The investment was well-timed, because the sum would only have evaporated in the coming inflation, had he tried to save it.

Planck had little time to enjoy his Nobel Prize. In November, even as his second grandchild, Emmerle, entered the world, her mother, Emma, died from complications. It was as if nature repeated some cruel experiment with Professor Fehling and each of Planck’s twin daughters. Neither had lived past the age of 30, and Max now fell fully into a depression. He buried Emma’s ashes in Grunewald. “The two beloved children, who could not get along without one another in life,” he wrote to relatives, “are now together for ever.”68

“Planck’s misfortune wrings my heart,” Einstein wrote to a friend. “I could not hold back the tears when I saw him. … He was wonderfully courageous and erect, but you could see the grief eating away at him.”69 Planck wrote to his most trusted colleague in physics, Hendrik Lorentz, “There have been times when I doubted the value of life itself.”70

Incredibly, he kept himself upright, throwing himself back into work and cherishing his remaining family: Marga, son Hermann, baby Grete Marie, infant Emmerle, and more than ever before, his son Erwin. The New Year brought back at least a glimmer of his deep optimism. “There are still many precious things on the earth and many high callings,” he wrote to a relative. “And the value of life in the last analysis is determined by the way it is lived.”71

Looking back, he would later credit his religious faith as the main source of strength in tragedy. While he did not subscribe to any specific Christian vision of God, he suffered no doubts in the existence of divine forces working in the universe. “If there is consolation anywhere it is in the Eternal,” he wrote to a colleague just a year after adult Emmerle attempted suicide in Erfurt. “And I consider it a grace of Heaven that belief in the Eternal has been rooted deeply in me since childhood.”72

In the weeks and months after Emma’s passing, solace sometimes arrived at the Planck home carrying a violin case. The trio of Einstein, Erwin, and Max Planck mourned within their music.73