IN 1987, WHILE WORKING AT APPLE, HUGH DUBBERLY COWROTE KNOWLEDGE NAVIGATOR, A VISIONARY FILM THAT PREDICTED NOT ONLY THE FUTURE OF TABLET COMPUTING, BUT THE CENTRALITY OF THE INTERNET IN THE WORK LIFE OF INDIVIDUALS.1 Dubberly’s practice at the time focused on traditional corporate communications and branding. But, as Knowledge Navigator demonstrated, he understood even then that future designers would have to negotiate complex networked environments, systems within systems—ecosystems. Dubberly went on to engage deeply with interactive design, first at Apple, then at Netscape, and ultimately through his own consultancy, Dubberly Design Office. As he asserts below, design values and approaches that grew out of the manufacturing world are shifting over. Design, and design education, should look to an organic-systems model as as we enter the age of biology.

DESIGN IN THE AGE OF BIOLOGY:

SHIFTING FROM A MECHANICAL-OBJECT ETHOS TO AN ORGANIC-SYSTEMS ETHOS

HUGH DUBBERLY | 2008

In the early twentieth century, our understanding of physics changed rapidly; now our understanding of biology is undergoing a similar rapid shift.

Freeman Dyson wrote: “It is likely that biotechnology will dominate our lives and our economic activities during the second half of the twenty-first century, just as computer technology dominated our lives and our economy during the second half of the twentieth.”2

Recent breakthroughs in biology are largely about information—understanding how organisms encode it, store, reproduce, transmit, and express it—mapping genomes, editing DNA sequences, mapping cell-signaling pathways. Changes in our understanding of physics, accompanied by rapid industrialization, led to profound cultural shifts: changes in our view of the world and our place in it. In this context, modernism arose. Similarly, recent changes in our understanding of biology are beginning to create new industries and may bring another round of profound cultural shifts: new changes in our view of the world and our place in it. Already we can see the process beginning. Where once we described computers as mechanical minds, increasingly we describe computer networks with more biological terms—bugs, viruses, attacks, communities, social capital, trust, identity.

HOW IS DESIGN CHANGING?

Over the past thirty years, the growing presence of electronic information technology has changed the context and practice of design. Changes in the production tools that designers use (software tools, computers, networks, digital displays, and printers) have altered the pace of production and the nature of specifications. But production tools have not significantly changed the way designers think about practice. In a sense, graphic designer Paul Rand was correct when he said, “The computer is just another tool, like the pencil,” suggesting the computer would not change the fundamental nature of design.3

But computer-as-production-tool is only half the story; the other half is computer-plus-network-as-media.

Changes in the media that designers use (the Internet and related services) have altered what designers make and how their work is distributed and consumed. New media are changing the way designers think about practice and creating new types of jobs. For many of us, both what we design and how we design are substantially different from a generation ago.

WHAT DO ELECTRONIC MEDIA AND DESIGNING HAVE TO DO WITH BIOLOGY?

Emerging design practice is largely information based, awash in the technologies of information processing and networking. Increasingly, design shares with biology a focus on information flow, on networks of actors operating at many levels, and exchanging the information needed to balance communities of systems. Modern design practice arose alongside the industrial revolution. Design has long been tied to manufacturing—to the reproduction of objects in editions or “runs.” The cost of planning and preparation (the cost of design) was small compared with the cost of tooling, materials, manufacturing, and distribution. A mistake in design multiplied thousands of times in manufacturing is difficult and expensive to fix.

The realities of manufacturing led to certain practices and in turn to a set of values or even a way of thinking. In the “modern” era, design practice adopted something of the point of view or philosophy of manufacturing—a mechanical object ethos.

Now as software and services have become a large part of the economy, manufacturing no longer dominates. The realities of producing software and services are very different from those of manufacturing products.

The cost of software (and “content”) is almost entirely in planning, preparation, and coding (the cost of design). The cost of tooling, materials, manufacturing, and distribution is small in comparison. Delaying a piece of software to “perfect” it invites disaster. Customers have come to expect updates and accept their role as an extension of developers’ QA teams, finding “bugs” that can be fixed in the next “patch.”

Services also have a different nature from hardware products. “Services are activities or events that create an experience through an interaction—a performance co-created at point-of-delivery.”4 Services are largely intangible, as much about process as final product. They are about a series of experiences across a range of related touch points.

Just as manufacturing formed its own ethos, software and service development is also forming its own ethos. The realities of software and service development lead to certain practices and to a set of values or even a way of thinking. Emerging design practice is adopting something of the point of view or philosophy of software and service development—an organic-systems ethos.

MODELS OF CHANGE

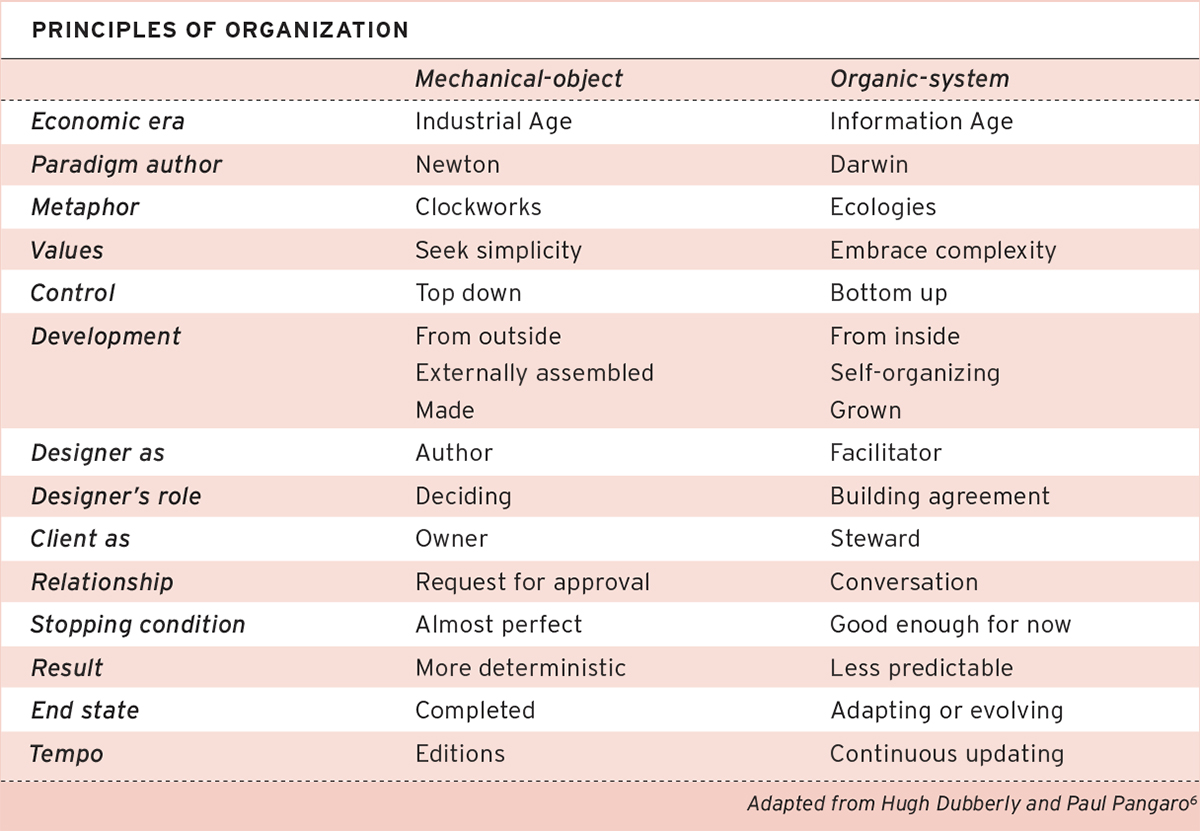

Several critics have commented on facets of the change from mechanical-object ethos to organic-systems ethos. This article brings together a series of models outlining the change and contrasting each ethos.

The models are presented in the form of an “era analysis.” Two or more eras (e.g., existing emerging eras or specified time periods) are presented as columns in a matrix with rows representing qualities or dimensions, which change across each era and characterize it.

The eras are framed as stark dichotomies to characterize the nature of changes. But experience is typically more fluid, resting along a continuum somewhere between extremes.

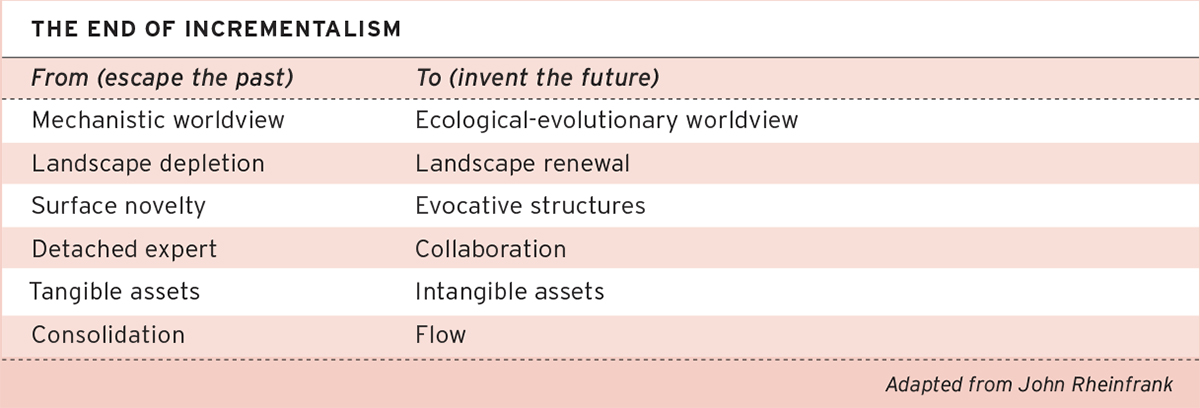

John Rheinfrank provided a broad summary of the change, which may serve as an introduction and an overview.5 He described a change in worldview similar to the change in ethos described above.

We may expand Rheinfrank’s model to describe how things come to be and the role of designers and their clients in the process.…

A CONCERN FOR USERS

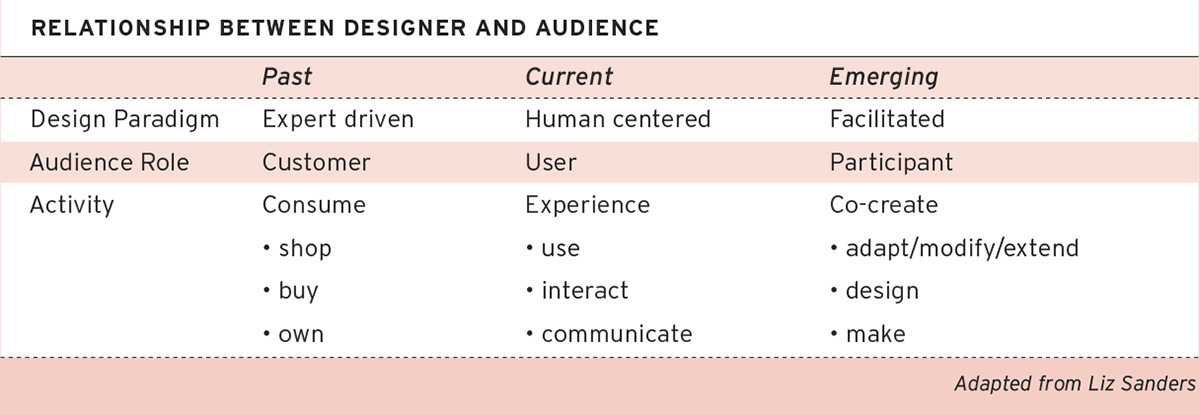

As Rheinfrank pointed out, the designer is moving from detached expert to collaborator. And the relationship between designer and constituent is moving from expert-patient to what Horst Rittel called “a symmetry of ignorance (or expertise),” where the views of all constituents are equally valid in defining project goals.7 Liz Sanders presents a similar argument with slightly different eras, introducing moving beyond human-centered or user-centered design.8

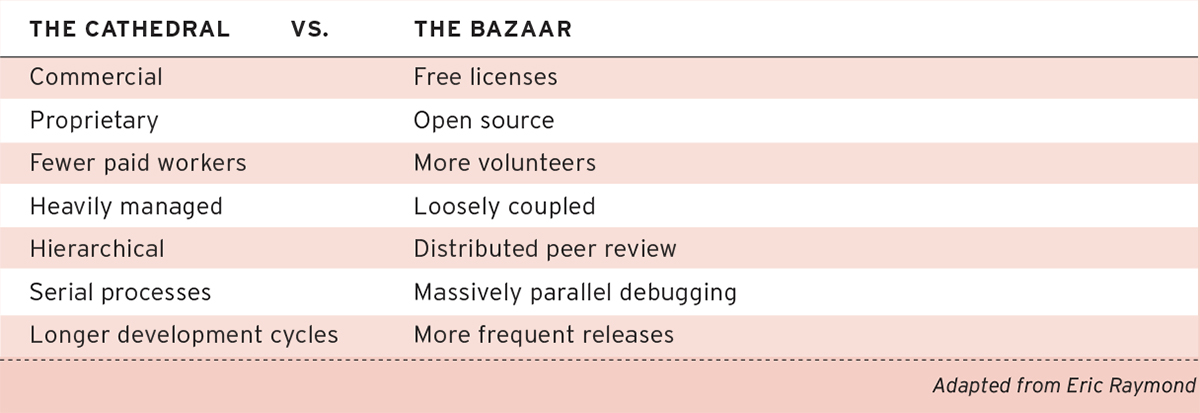

Co-development is also a fundamental tenet of open-source software. Eric Raymond wrote, “Treating your users as co-developers is your least-hassle route to rapid code improvement and debugging.” He added, “Even at a higher level of design, it can be very valuable to have lots of co-developers random walking through the design space near your product.” Raymond famously contrasted “cathedrals carefully crafted by individual wizards or small bands of magi working in splendid isolation” to “a great babbling bazaar of differing agendas and approaches.” He suggested traditional “a priori” approaches will be bested by “self-correcting systems of selfish agents.”9

THE RISE OF SERVICE DESIGN

The shift from industrial age to information age mirrors, in part, a shift from manufacturing economy to service economy. In the new economy, as former Wired editor Kevin Kelly put it, “Commercial products are best treated as though they were services. It’s not what you sell a customer, it’s what you do for them. It’s not what something is, it’s what it is connected to, what it does. Flows become more important than resources. Behavior counts.”10

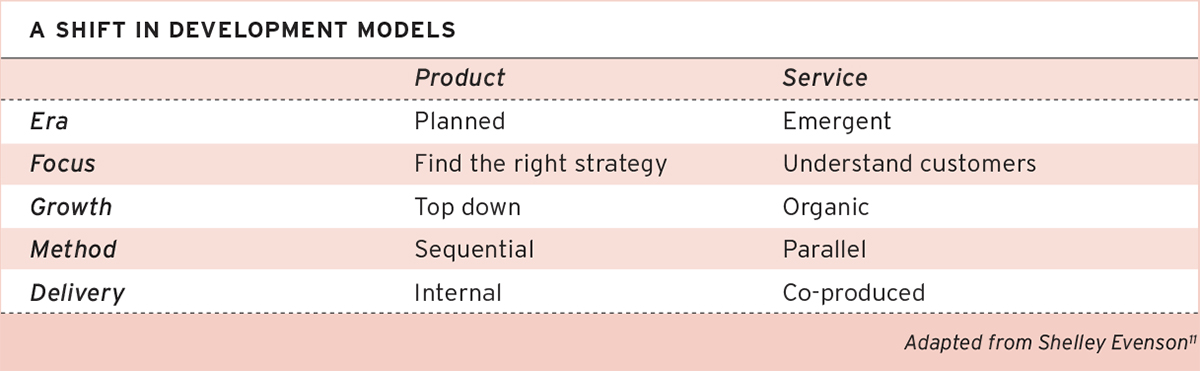

Early on, Shelley Evenson saw the importance of service design, and she has led U.S. designers in developing the field. She has provided a framework contrasting traditional business-planning methods with service-design methods. Her framework parallels the larger change in ethos we’ve been discussing.

Typically, responsibility for designing individual artifacts rests pretty much with one individual, but systems design almost by definition requires teams of people (often including many specialties of design). The need for teams of designers can be seen easily in the design of software systems and service systems, where many artifacts, touch points, and subsystems must be coordinated in a community of cooperating systems. For example, “Web-based services” or “integrated systems of hardware, software, and networked applications” require development and management teams with many specialties.

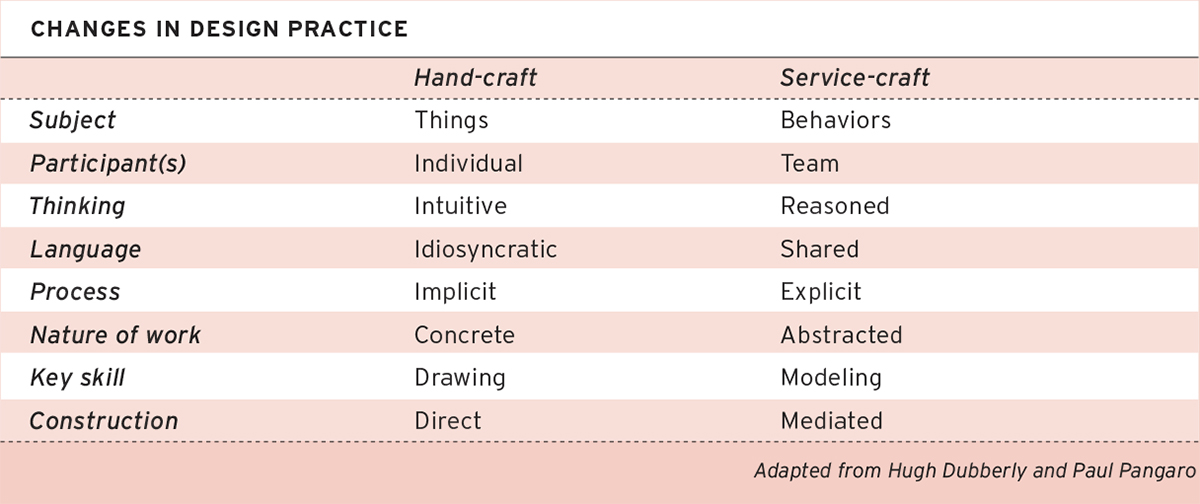

The work of an individual designer on an individual artifact has often been characterized as “hand-craft.” In contrast, Paul Pangaro and I have proposed “service-craft” to describe “the design, management, and ongoing development of service systems.” Design practice in a hand-craft context differs markedly from design practice in a service-craft context. Having assembled a team, care must be taken to negotiate goals, set expectations, define processes, and communicate project status and changes in direction. Care must also be taken to create opportunities for new language to emerge and to create capacity for coevolution between service and participants.

We also noted that “hand-craft has not gone away, nor is service-craft divorced from hand-craft. Hand-craft plays a role in service-craft (just as in developing software applications, coding remains a form of hand-craft). While service-craft focuses on behavior, it supports behavior with artifacts. While service-craft requires teams, teams rely on individuals. Service-craft does not replace hand-craft; rather, service-craft extends or builds another layer upon hand-craft.”12…

HUGH DUBBERLY

Interview with Steven Heller 2006

SUSTAINABLE DESIGN

The mechanical-object/organic-system dichotomy also appears vividly in discussions about ecology. Much of our economy still depends on “consumers” buying products, which we eventually throw “away.” William McDonough and Michael Braungart have pointed out that there is no “away,” that in nature, “waste is food.” They urged us to think in terms of “cradle to cradle” cycles of materials use, and they suggested manufacturers lease products and reclaim them for reuse.13 Theirs is another important perspective on the idea of product as service.

Architects, too, have begun to design for disassembly and reconfiguration. Herman Miller recently published a manifesto on programmable environments, talking about the need for “pliancy” in the built environment and echoing the language of The Cathedral and the Bazaar while discussing building design.14

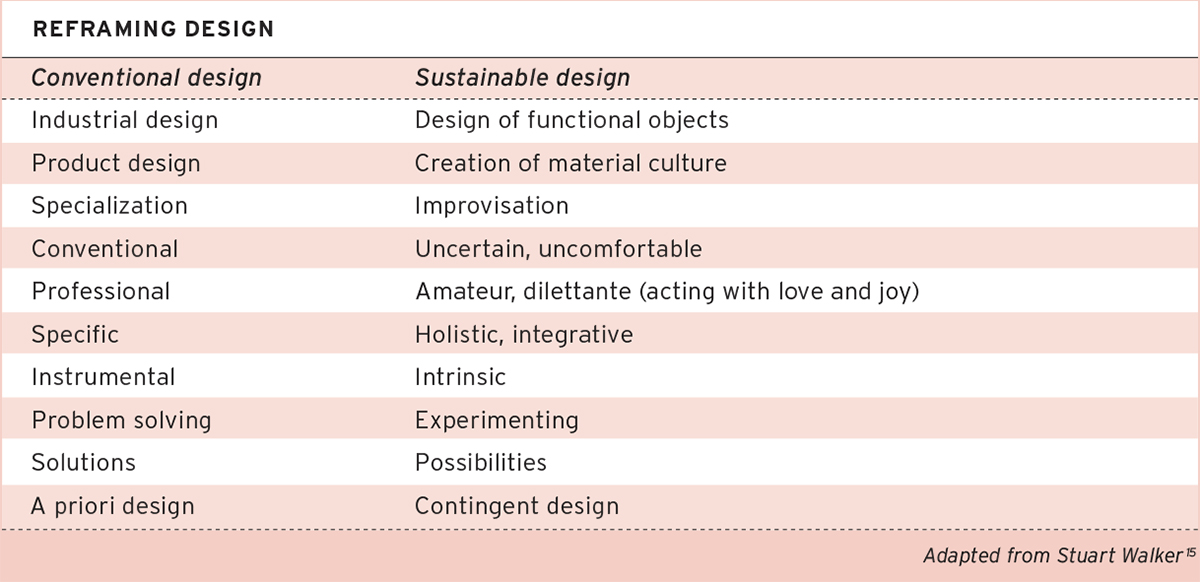

Sustainable design is emerging as an issue of intense concern for designers, manufacturers, and the public. The same sort of systems thinking required for software and service design is also required for sustainable design. This provides further impetus for changing our approach to design education.

Stuart Walker, professor of design at the University of Calgary, has written, “Only by fundamentally changing our approaches to deal with the new circumstances can we hope to develop new models for design and production that are more compatible with sustainable ways of living. Wrestling with existing models and trying to modify them is not an effective strategy.”

EARLY PARALLELS

The current shift from a mechanical-object ethos to an organic-systems ethos has been anticipated in earlier shifts.

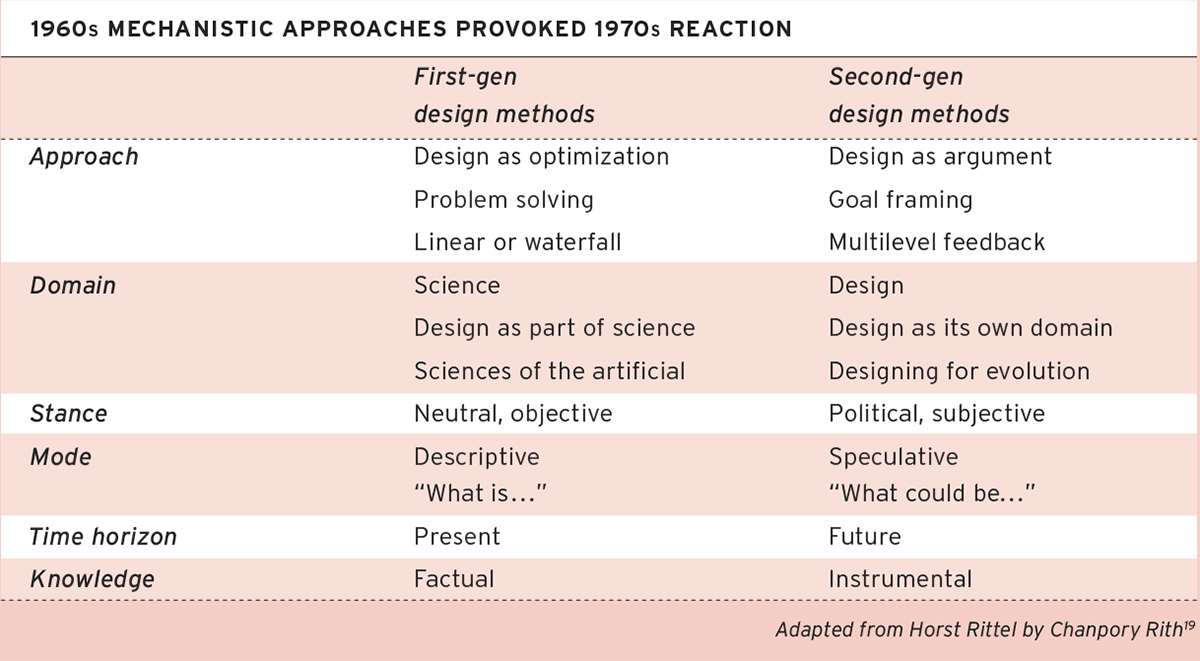

In the mid-1960s, architects and designers began to focus on “rational” design methods, borrowing from the successes of large military-engineering projects during the war and the years following it. While these methods were effective for military projects with clear objectives, they often proved unsuccessful in the face of social problems with complex and competing objectives. For example, methods suited to building missiles were applied to large-scale construction in urban-redevelopment projects, but those methods proved unsuited to addressing the underlying social problems that redevelopment projects sought to cure.

Horst Rittel proposed a second generation of design methods, effectively reframing the movement, casting design as conversation about “wicked problems.”16 His proposal came too late or too early for the design world, which had already moved on to “postmodernism” but had not yet encountered the Internet.

Rittel’s work did attract attention in computer science (he was a pioneer in using computers in design planning), where “design rationale” (the process of tracking issues and arguments related to a project) continues as a field of research. More recently, Rittel’s work has attracted attention in business school publications addressing innovation and design management.17, 18

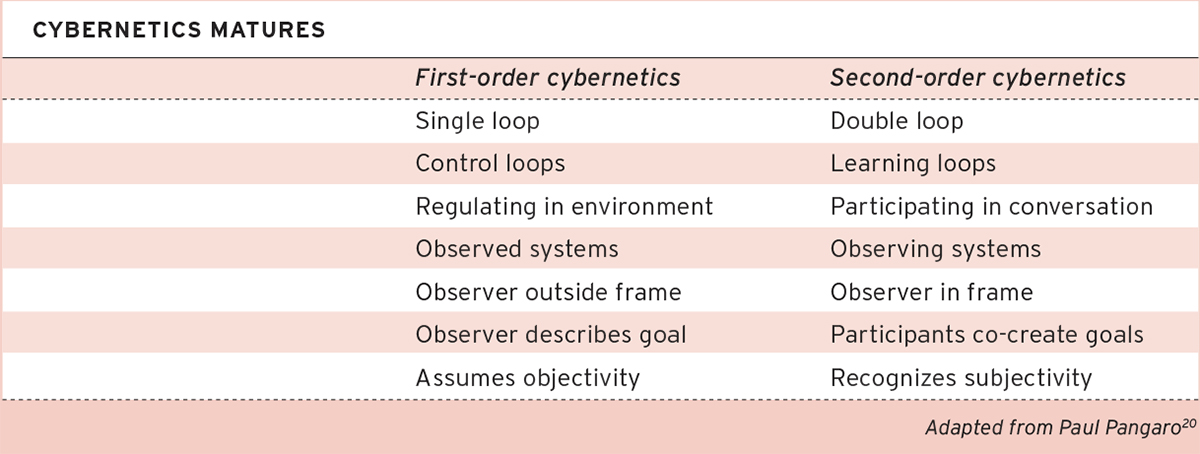

Paul Pangaro and I have also noted that Rittel’s framing of first- and second-generation design methods parallels Heinz von Foerster’s framing of first- and second-order cybernetics. Von Foerster described a shift of focus in cybernetics from mechanism to language and from systems observed (from the outside) to systems that observe (observing systems).

In 1958 von Foerster formed the Biological Computer Laboratory at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. He brought in Ross Ashby as a professor and later Gordon Pask and Humberto Maturana as visiting research professors. The lab focused on problems of self-organizing systems and provided an alternative to the more mechanistic approach of AI [artificial intelligence] followed at MIT by Marvin Minsky and others.21 In a way, von Foerster anticipated the shift from mechanical-object ethos to organic-systems ethos in computing, design, and perhaps the larger culture.

WHAT DO THESE CHANGES MEAN FOR DESIGN EDUCATION?

As design moves into the age of biology and shifts from a mechanical- object ethos to an organic-systems ethos, we should reflect on how best to prepare for coming changes in practice. At a recent conference on design education, Meredith Davis described “the distance between where we are going in the practice of graphic design and longstanding assumptions about design education.”22…

Davis (building on [Sharon] Poggenpohl and [Jürgen] Habermas) distinguished between two models of practice, “know how” and “know that,” “design as a craft and design as a discipline.” This distinction parallels the distinction between hand-craft and service-craft that Pangaro and I propose above. Davis asserted, “college design curricula, and the pedagogies through which we deliver them, are based almost exclusively on the first model of practice, on know how, and don’t acknowledge issues that drive emerging practices.”

Davis’s argument and framing are closely related to changes described in this article. Changes that Davis advocates are consistent with the spirit of the new ethos and aimed at helping designers grasp the nature of organic-systems work and preparing them for practice in the age of biology.

Of course, not all designers welcome the coming change. Form giving remains a large part of design practice and design education. Will some designers be able to continue to practice primarily as form givers? That seems likely. But already a schism is developing both in design practice and design education, as individuals and institutions choose to focus on either form giving or on planning. It remains to be seen if one person, one firm, or one school can bridge the divide and excel at both.

1 Alan Kay contributed to the concept of Knowledge Navigator. John Sculley premiered the film as part of his keynote at Educom, a higher-education conference. To read more about this, see Bud Colligan, “How the Knowledge Navigator Video Came About,” Dubberly Design Office, November 20, 2011, http://www.dubberly.com/articles/how-the-knowledge-navigator-video-came-about.html.

2 Freeman Dyson, “The Question of Global Warming,” New Yorker 55, no. 10 (June 2008).

3 Paul Rand, personal conversation with author during a visit to the Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, Calif., 1993.

4 Shelley Evenson, “Designing for Service: A Hands-On Introduction,” presentation at CMU’s Emergence Conference, Pittsburgh, Pa., September 2006.

5 John Rheinfrank, “The Philosophy of (User) Experience,” presentation at CHI 2002/AIGA Experience Design Forum, Minneapolis, Minn., May 2002.

6 Hugh Dubberly and Paul Pangaro, joint course development, Stanford, 2000–2008.

7 Horst Rittel, “On the Planning Crisis: Systems Analysis of ‘First and Second Generations.’” Bedrifts Økonomen 8 (1972): 390–396.

8 Liz Sanders, “Generative Design Thinking” presentation, San Francisco, June 2007.

9 Eric Raymond, “The Cathedral and the Bazaar,” v3.0, 2000, available at http://www.catb.org/~esr/writings/cathedral-bazaar/cathedral-bazaar/cathedral-bazaar.ps.

10 Kevin Kelly, Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems, and the Economic World (New York: Addison Wesley, 1994).

11 Shelley Evenson, “Experience Strategy: Product/Service Systems,” presentation, Detroit, 2006.

12 Hugh Dubberly and Paul Pangaro, “Cybernetics and Service-Craft: Language for Behavior-Focused Design,” Kybernetes 36, no. 9/10 (April 2007).

13 William McDonough and Michael Braungart, Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things (New York: North Point Press, 2002).

14 Jim Long, Jennifer Magnolfi, and Lois Maasen, Always Building: The Programmable Environment (Zeeland, Mich.: Herman Miller Creative Office, 2008).

15 Stuart Walker, Sustainable by Design: Explorations in Theory and Practice (London: Earthscan, 2006).

16 Ibid.

17 Jeanne Liedtka, “Strategy as Design,” Rotman Management (Winter 2004): 12–15.

18 John C. Camillus, “Strategy as a Wicked Problem,” Harvard Business Review (May 2008): 99–106.

19 Chanpory Rith, personal communication with author, 2 July 2005.

20 Paul Pangaro, personal communications with author, 2000–2008.

21 Albert Müller, “A Brief History of the BCL: Heinz von Foerster and the Biological Computer Laboratory,” Österreichische Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaften 11, no. 1 (2000): 9–30. Translated by Jeb Bishop and since republished in “An Unfinished Revolution?”

22 Meredith Davis, “Toto, I’ve Got a Feeling We’re Not in Kansas Anymore…,” presentation at the AIGA Design Education Conference, Boston, April 2008.