Victory Rides

the Divine Wind

The Kamikaze and the Invasion of Kyushu

D. M. Giangreco

The lecture on logistic considerations for the recent invasion of Kyushu was going well. Nearly 160 students, faculty, and guests filled Pringle Auditorium at the Naval War College on this blustery Tuesday evening in November 1946 to hear Adm. Richmond Kelly Turner. A 1908 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, Turner had commanded the Pacific Fleet Amphibious Force of more than 2,700 ships and large landing craft during the invasion.1 The 101 students in the class of 1947 were veterans of the largest war in history, and the transfer of nearly all of the Atlantic Fleet's assets to the Far East after Normandy had insured the participation of every navy and marine officer at the college in either the final, mammoth operation at Kyushu or the even more massive operation planned for later in the Tokyo area. Likewise, all but two of the dozen army, air force, and coast guard officers—plus the single student from the State Department 2—had seen service in the Pacific. The college's new president, Adm. Raymond A. Spruance, had himself commanded the 5th Fleet during the invasion and whispered to an aide that his longtime friend and colleague was “in top form tonight.”3

It was good to see Turner doing well, and Spruance reflected that speaking before the assembled officers—particularly these officers—would do him nothing but Turner had only two weeks earlier concluded his testimony in the last of three Congressional inquiries held after the armistice with Imperial Japan, and even before those, had been summoned back to Washington on three separate occasions in the midst of the war to testify on matters relating to December 7, 1941. During those earlier proceedings, he had been subjected to considerable cross-examination because of his prewar duty in the navy's War Plans Division,4 and the first hearings after the armistice again dealt with Pearl Harbor. There was very little of substance that he had been able to add to the second postwar hearings, since the joint House-Senate committee was investigating events surrounding the tactical use of nuclear weapons and the resultant deaths and sickness recorded so far among some 40,000 U.S. military personnel. However, the most recent hearings of the Taft-Jenner committee had been another matter entirely, and Turner rapidly became the focus of its investigation into why the navy, after more than a year of experience battling Japanese suicide aircraft, had been “caught napping” by the kamikazes off Kyushu.

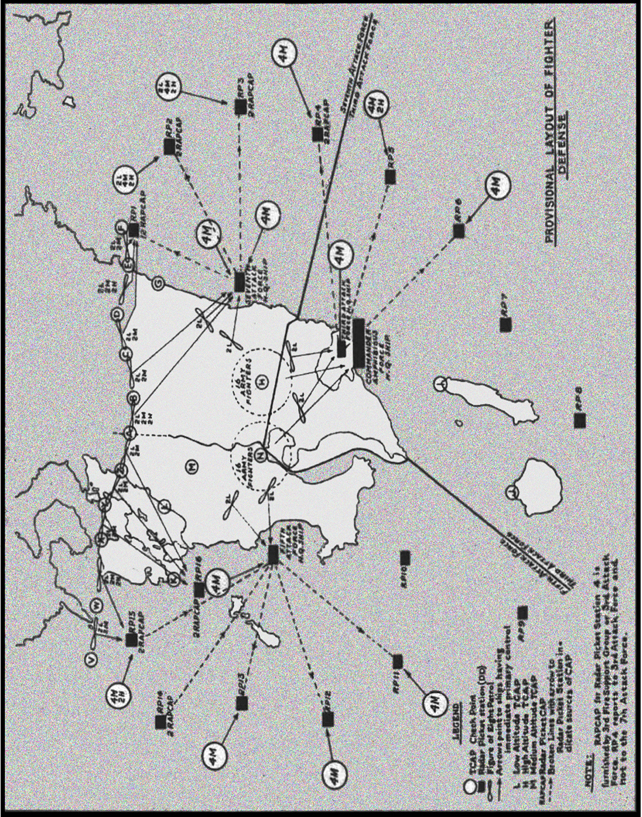

Map 15. Provisional Layout Fighter Defense

“Pearl Harbor II,” as it was dubbed by the press, saw thirty-eight troop-laden Liberty ships and LSTs, along with a score of destroyers and twenty-one other vessels, struck within sight of the invasion beaches during X-Day and X+l.5 Six other vessels were crashed by shinyo speedboats filled with explosives that darted into the assault groups during the confusion, and a further ten Liberty ships were hit by kamikazes from X+2 to X+6. The bulk of the 29,000 dead and missing were ground troops, with an equal number of soldiers and marines turned into stunned refugees after discarding all their gear during frantic efforts to abandon burning and sinking transports. Finely choreographed assault landings had been terribly disrupted by the incessant attacks and rescue operations. The subsequent lack of proper resupply and reinforcement resulted in nearly triple the anticipated ground-force casualties through X+30 and an unprecedented—and bloody—stalemate until X+20 on the northeasternmost six of the thirty-five invasion beaches.

More men had been lost in the first two weeks at Kyushu than at the Battle of the Bulge and Okinawa combined, and critics were looking hard for someone's head to stick on a pike (an “army” pike). Adm. Chester Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet, refused to offer up Turner for sacrifice and took full responsibility for the debacle (although it was certainly obvious that there was plenty of blame to go around). Still, the hearings had been brutal, and Gen. Douglas MacArthur, from his headquarters in Manila, made it clear that he believed Turner's “failure to safeguard the lives of our gallant soldiers and marines” had forced America into “an incomplete victory worse than Versailles.” Tonight was the tough old admiral's first public address since the hearings, and Spruance did all he could to keep news of the event confined to the tight naval community on Coasters Harbor Island in Narragansett Bay's East Passage. In fact, the only people in attendance not from the Naval War College or Newport Naval Base were retired marine three-star general Holland Smith, who was visiting the son of a longtime colleague, and George Kennan, an assistant to newly appointed Secretary of State George C. Marshall.

The students were held spellbound by the man Spruance regarded as the finest example of that rare combination, a strategic thinker and a fighter ready and willing to take responsibility and plunge into battle.6 Very few of the officers had actually laid eyes on “Terrible” Turner during the Pacific War, and the first round of questions after his presentation were tentative, almost softball. Spruance expected that this wouldn't last long, and it didn't.

“Sir, right from the beginning, at Leyte, when the Japs succeeded in forcing a redisposition of the carriers, we started to lose a lot of ships to the suiciders and even conventional attacks. Was it the loss of those transports and LSTs that slowed down the airstrip construction ashore and just made a bad situation worse from the standpoint of air defense?”

A score of supply ships along with a half-dozen destroyer-type vessels had unexpectedly been lost during November 1944. The kamikazes had drawn first blood on October 25-26, when a five-plane raid sank the escort carrier St. Lo and damaged three similar carriers. This had prompted many more young Japanese fliers to volunteer for the Shimpu (Special Attack Corps) unit, and on October 30 a kamikaze attack damaged three large fleet carriers so severely that they had to be pulled back to the Ulithi anchorage for repairs. Within days another large flattop fell victim, as did three more toward the end of November.7 This stunning disruption of carrier airpower spelled the loss of the ships referred to by the questioner and had a pronounced effect on the conduct of the ground campaign as well. Leyte had not been Turner's show. Vice Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid had been commanding, and Turner chose his words carefully.

“We expected to take losses, but the nature of the Jap attacks was a complete surprise. We expected that our fighter sweeps would take out most of his airpower in the Philippines before the landings. The feeble response to Bill [Admiral William F.] Halsey's earlier raid in September 1944 led us to conclude that Jap strength in the islands was far weaker than it should have been and we, in fact, canceled intermediate operations and pushed KING II up a full sixty days.8 There was no way to anticipate the tactics that were used against us. As to air-base development on Leyte, it was not the loss of shipping, but the weather and resultant conditions on the ground that stalled the best efforts of army engineers. We'd owned those islands for over forty years yet did not have a clue as to just how unsuitable the soil conditions were in the area where we sited the Burauen Airfield complex.

“Everyone remembers the newsreels of the theater commander wading ashore from a Higgins boat—I'm sure he did it in one take—[laughter] and his pronouncement that he had 'returned' but what few people know is that he was supposed to have retaken Leyte with four divisions and have eight fighter and bomber groups striking from the island within forty-five days of the initial landings. Nine divisions and twice as many days into the battle, only a fraction of the airpower was operational because of that awful terrain.9 The fighting on the ground had not gone as planned either. The Japs even did an end run, briefly isolated 5th Air Force headquarters, and captured much of the airfield complex before the army pushed them back into the jungle.10 Colonel?”

Having closed with a comment on the army, he motioned to one of several soldiers attending the college. He noted that the officer wore the scarlet crossed-arrow patch of the 32nd Infantry Division, which fought battles on Leyte's Corkscrew, Kilay, and Breakneck ridges.11

“Thank you, sir. In light of the fact that the lack of air interdiction allowed the enemy to transfer four divisions plus various independent brigades and regiments to the island from Luzon,12 do you feel that the amount of time to take Leyte was excessive?”

The admiral was unfazed by the implied rebuke. “No. Buoyed by pilot reports of both real and imagined losses to our fleet, the Japs decided to conduct their main battle for the Philippines on Leyte instead of Luzon. We had originally intended Leyte to act as a springboard to Luzon in exactly the same way that Kyushu was to act as the last stop before Tokyo. But the important thing to remember is that no matter which island we fought them on, the Japs had only a finite number of troops available in the Philippines. Over eighty percent of Jap shipping used during their effort was eventually sunk during later resupply missions, but we obviously would have liked to have sent them to the bottom sooner. The conquest of Leyte eventually involved over 100,000 more ground troops than anticipated and took us so long to accomplish that the island never became the major logistical center and air base we intended. 13 My point is that the Japs were turning out to be much more resourceful than we anticipated and this affected operations all across the board. Does that answer your question?”

“Yes, sir,” said the colonel. But he later told the head of the college's logistics department, Rear Adm. Henry Eccles, that he had considered commenting that the dearth of army and navy air interdiction was still being felt months later; that a number of Japanese units were actually evacuated from Leyte when ordered off in January 1945,14 and that he didn't like fighting the same Japs twice. Eccles said that the colonel had been wise not to press the issue.

Many in the audience now raised their hands with questions, and Turner called on a lieutenant commander from the junior class.

“Admiral, could you comment on the fighter sweeps conducted over southern Japan ahead of the invasion?”

Turner asked him if he could be more specific.

“Yes, sir. Why was there so little attrition of their air forces ahead of Kyushu?”

This had been a subject of much heated discussion both in the press and in the wardrooms. It had even been rehashed in great detail earlier that day in Luce Hall, with the head of the college's Battle Evaluation Group, Commodore Richard Bates, and about two dozen students.

Kamikazes “Glued to the Ground”

“To a very real degree, gentlemen, we were the victim of our own success,” said Turner. “Throughout the war, increasingly effective sweeps by our aircraft—and the army's fighters and medium bombers—played havoc with Japanese air bases. And we were sure that many of their aircraft would certainly be destroyed by preinvasion fighter sweeps. But to destroy them on the ground, we would have had to know where they were.15 Anticipating that attacks would only grow worse as we neared the home islands in force, the Japs stepped up the dispersion of their units and spread aircraft throughout more than 125 bases and airfields that we knew of, and the number was apparently far larger.16 This effort intensified after we caught hundreds of them on the ground at Kyushu bases preparing for suicide runs at Okinawa.17 As for the planes slated for use as kamikazes, they didn't require extensive facilities, and were hidden away to take off from roads and fields around central billeting areas.18 In addition, dispersal fields were being constructed by the dozen, while use of camouflage, dummy aircraft, and propped-up derelicts performed as desired during our strikes against known facilities.”19

Spruance suspected that the questioners already knew the answers, or pieces of the answers, almost as well as Turner, but were deeply interested in the admiral's unique insight into Pacific operations. The exchange now moved at a very fast clip.

“Sir, intelligence reports made it clear that there were a large number of aircraft available in Japan,20 but I was surprised that even though we were bombing virtually everything we wanted at will, they would not come up and fight.”

“You weren't the only one,” replied Turner. “After some initial sparring with our carriers and Far East air force elements flying out of Okinawa, the Japs essentially glued their aircraft to the ground in order to preserve them for use during the invasions. We all know the story. The few high-performance aircraft like the Raiden were used against the B-29s, but that was it. There was no significant employment of aircraft, even during the approach of our fleets, since the Japs believed that being drawn out early would cause needless losses and correctly anticipated that we would attempt to lure their aircraft into premature battle through elaborate feints and other deception measures. They planned for a massive response only when they confirmed that landing operations had commenced.”21

“Sir,” said another student, “it has been reported that the Japanese had been planning to use suiciders well before Leyte.”

Turner nodded. “The codicil to the armistice agreement which allows us to formally discuss the conduct of the war with Japanese officers of equal rank brought out some interesting information on that. These discussions, by the way, are continuing. They are certainly not controlled interrogations and the information is sometimes questionable, but the discussions overall have been frank and useful.” The admiral didn't say it, but he was as amazed as anyone that talks of that nature were even taking place. “As to your question, the growing supremacy of our fleet prompted some Japanese leaders to contemplate the systematic use of suicide aircraft as early as 1943. But it wasn't until late the following year, after they'd lost many of their best pilots at Midway, the Solomons, New Guinea, and the Marianas, that the kamikaze was seriously considered as a last-ditch alternative to conventional bombing attacks. 22 We'd known this for some time. What we have just learned from our discussions is that the first time that orders were actually handed down for employment of suicide tactics was July 4, 1944, at Iwo [Jima]. Since all the kamikazes were shot down before reaching our ships, we never knew a thing about it.”23

“Sir, right to the end there were always Jap pilots who made no attempt to crash our ships. Was that intentional; part of a systematic employment?”

Turner nodded again. “Yes, experienced pilots, deemed too valuable to sacrifice, were to provide fighter cover or fly conventional strikes. In fact, when some of them volunteered for the one-way missions, they were denied the 'honor' of killing themselves for the emperor.”24

“Sir, with the benefit of hindsight it seems apparent to me that if the tactics employed at Kyushu had been employed at Leyte, their planes would have been able to crash a lot more ships. When they had altitude, you could pick 'em up without much trouble. But if they'd come out of those hills—coming in low rather than flying up here where we could pick 'em up early around 10,000, 20,000 feet and diving down—frankly, the Japs could have massacred our transports in the Philippines. The only upside is that it would have made the danger off Japan's coast more clear.”25

“You never like to take losses,” said Turner, “but if the Japs had used their aircraft as you described at Leyte, the lessons learned from that battle would indeed have made a difference at Kyushu. Okinawa represented the first coordinated effort by Jap pilots to use cliffs and hills to foil our radar, but the size of the island and the distances they had to fly from their bases on Formosa and Kyushu, together with the fact that the Japs had only just begun to experiment in this area, initially limited the usefulness of such tactics. Nonetheless, they did enjoy numerous successes when kamikazes appeared so suddenly out of the radar clutter that even fully alert crews of ships close ashore had little time to respond. And of course, response times naturally stretched out once the fatigue of being constantly at the alert began to set in. All kinds of tactical innovations were developed ad hoc as we gained more experience with the new threat. Ideas were shared throughout the fleet and crews incorporated any innovations they thought would be useful— anything to increase point defense capabilities by shortening antiaircraft weapons' response times. Would you like to comment on that, Commodore Bates?”

“Certainly, sir. By summer 1945, slewing sights for the five-inch gun mount officers' station were helping to ensure quick, non-radar-directed action, and many ships had begun to rig cross connections between their five-inch guns' slow Mark 37 directors and the 40mm guns' more nimble Mark 51s. These changes—and a projectile in the loading tray—enabled the fiveinchers to come on line more quickly to counter sudden attacks, but switch back to the longer-range Mark 37 directors if radar found possible targets at a more conventional range. The new Mark 22 radar, which allowed early and accurate identification of incoming aircraft, was also widely distributed by the time of Majestic.26 It had little impact on the fighting close to shore, but proved its worth over and over again with the carriers.

“Prior to the appearance of the kamikazes, 20mm anti-aircraft guns had been the greatest killers of Jap planes. After that, however, their lack of hitting power rendered them little more than psychological weapons against plunging kamikazes. Commanders relied increasingly on the larger 40mm guns, because they could blast apart a closing aircraft. As more became available, we jammed additional mounts of the twin- and quad-40s into already overcrowded deck spaces on everything from minesweepers and LSTs to battleships and carriers.”

A voice rang out from the back of the hall, “But we wouldn't let you take away our 'door knockers'!” a remark followed by general laughter.

Admirals Turner and Spruance grinned widely at the shouted comment, but the chief of the Battle Evaluation Group offered only a half smile.

“As I was saying, although 20mm guns had proved ineffective against a plunging kamikaze, that did not mean crews were eager to do away with them in order to free up deck space. These weapons at least had the advantage of not being operated electrically. Even if a ship's power was knocked out, the 'door knockers' could still supply defensive fire.27 The new three-inch/ 50 rapid-fire gun is a wonderful weapon. One gun is as effective as two—that's two—quad 40s against conventional planes, and against the Baka rocket bomb the advantage was even more pronounced. It took fully five quad 40s [twenty guns] to do the work of a single three-inch/50.28 Unfortunately, very few crews had been properly trained for it by Majestic.

“Reviewing the outcome of the extended radar picket operations off Okinawa,” continued Bates, “COMINCH [Commander in Chief, United States Fleet] came to the conclusion that one destroyer cannot be expected to defend itself successfully against more than one attacking enemy aircraft at a time— many did, in fact, but were eventually overwhelmed—and noted that, in the future, a full destroyer division should be assigned to each picket station if the tactical situation allowed such a commitment of resources.29 We were able to do this at four of the sixteen picket stations at Kyushu, but all the other stations had to make do with a pair of destroyers and two each of those special gunboats made especially for operations against Japan [LSMs with one dual and four quad 40mm mounts], which were far more heavily armed than the gunboats used at Okinawa.

“COMINCH also found that while large warships' and aircraft gunnery was not affected greatly by evasive maneuvers, violent turns by a diminutive destroyer to disturb the aim of the kamikaze, or to bring more guns to bear during a surprise attack, caused extreme pitches and rolls that degraded accuracy. Gunnery improved dramatically when destroyers performed less strident maneuvers, even if fewer guns could be brought into play quickly.”

The officer students were more willing to respectfully interject themselves into Commodore Bates's comments than they were to interrupt Turner, and a former destroyer captain immediately spoke up.

“That's theoretically true, sir, but anyone who experienced the Philippines and Okinawa, or the raids on Japan, knows that in most instances you can't actually do that and live to tell about it. The suiciders had apparently been told that, since they didn't need the broad targets normally required for aiming bombs, the best results in their type of mission would come from bow—or stern—on attacks that allowed them to be targeted by the least amount of defensive fire.30I'd seen new skippers follow COMINCH advice on this matter and the only thing that happened was a sort of Divine Wind 'crossing the T,' made much easier by less radical destroyer maneuvers.”

A former executive officer chimed in. “I've been told that even a novice pilot can be trained to perform skids, or sideslips, and when we were hit—I was on the Kimberly target skidded to always remain in the ship's wake—and we were on hard right rudder! Only the afterguns could bear, and each 5-inch salvo blasted the 20mm crews off their feet. The Val came in over the stern, aiming for the bridge, and crashed aft the rear stack between two 5-inch mounts.”31

Admiral Turner was not surprised that, given an opportunity, the talk turned to tactics. He quickly moved to elevate the discussion.

“Early in the war, after Pearl Harbor, Malaya, and the Java Sea, things looked bleak for our surface ships—and those of the Japanese as well. Naval aircraft were clearly dominating any vessels they came up against. The fielding of the proximity fuse32 in 1942 and 1943 increased the odds that our ships would fight off their aerial tormentors, and by 1943—just two years after Pearl Harbor—the balance of power had firmly shifted into America's favor as our industrial base, our training base, added warships, attack aircraft, and large numbers of skilled aviators to the fleet. The duel between ships' guns and aircraft, however, came full circle with the advent of the kamikaze. Destroying ninety percent of an inbound raid had been considered a success before Leyte, 33 but the damage inflicted by even one suicide aircraft could be devastating. It was obvious that the invasion of Japan would entail terrible losses, and we moved to defeat the threat through increased interdiction, effective command and control, more guns, and everything we could think of to knock them down before they reached our ships.”

“Sir,” interjected a member of his audience, “one of the points noted over and over again in intelligence reports before Kyushu was that the Nips didn't even have enough gas to train their new pilots; that, cut off from their oil in the Dutch territories and with all their refineries destroyed by the [B-29] Super-forts, they would be hard-pressed to maintain flight operations. I don't really know anyone at my level who bought into this, but was it a factor in why we provided so little air cover at the landing sites?”34

“I'll answer that in two parts,” said Turner after a moment's deliberation. “First, everything you said about their ability to import and refine oil was true, but not to the degree that some believed. The other part of the picture dealt with evidence from signals intelligence and the Japs' lack of fleet activity, which appeared to be a clear sign that they had run out of gas. Their navy had drastically curtailed combat operations because of a lack of heavy fuel oil, and we were aware that shortages were the primary factor behind the ratcheting down of flight hours in their pilot training. Moreover, reports obtained from neutral embassies also indicated that the civilian population had not only been deprived of liquid fuel but that badly needed foodstuffs, such as potatoes, corn, and rice, were also being requisitioned for synthetic fuel production. 35 We also believed that our attacks had destroyed nearly all of their storage capacity. So, while we were aware that some large number of aircraft had been successfully hidden from us, the recurring weakness of their response to our attacks reinforced the idea that those aircraft were no longer able to defend effectively.

“What we did not know was that the Japs had made a conscious decision early on to build up decentralized fuel reserves separate from those used for training, a reserve which would only be tapped for the final battles. They had seen the writing on the wall when we reestablished ourselves in the Philippines, and succeeded in rushing shipments past our new bases in February and March before that avenue was choked off. Although we sank roughly two-thirds of the tankers running north, four or five got through with 40,000 tons of refined fuel. This shipment and some domestic production formed the core of what became Japan's strategic reserve,36 which included 190,000 barrels of aviation gas in hidden army stockpiles and a further 126,000 barrels held by the navy. 37 To give you an idea of just how much gas we're talking about here, the Japs used roughly 1.5 million barrels during flight operations against our fleet at Okinawa38but—and this is important—at Okinawa they had to fly roughly triple the distances they did over Japan.

“Their perceived inability to send up large numbers of aircraft encouraged us to believe that the landing area's immediate defense could be left to our escort carriers, while the nearly 1,800 aircraft of Task Force 58's fleet carriers were assigned missions as far north as 600 miles from Kyushu, well beyond Tokyo. Aircraft from only two of Admiral Spruance's task groups were dedicated to suppression efforts north and east of the screen thrown up by Adm. [Clifton A. E] Sprague's escorts. I and others argued strenuously—and unsuccessfully—that this was taking a lot for granted. We didn't need a show of force all up and down Honshu. We needed a blanket of Hellcats and Corsairs at the decisive point. We needed them at Kyushu. Yes, command and control would be extremely difficult, maybe impossible, with that many planes concentrated over that airspace. But it would be worth it if the Japs succeeded in massing for an all-out lunge at the transports—and that's exactly what they did.”

“Sir, weren't there also fewer escort carriers taking a direct part in the invasion than there might have been?”

“Yes,” replied Turner, “but a certain amount of that was unavoidable. A total of thirty-six escort carriers took part in some facet of Majestic, but many had to be siphoned off to protect the far-flung elements of the invasion force. For example, four escort carriers were assigned to provide cover for slow-moving convoys plying the waters between the Philippines and Kyushu against more than 600 Jap aircraft that could be brought into play through their bases on Formosa.39 Sprague had sixteen flattops with approximately 580 aircraft available for both the direct support of the landing force and defense of the assault shipping.40 Plans called for roughly 130 aircraft to be on-station from dawn to dusk to provide a last ditch defense of the landing area.41 Of course, far more aircraft were required to maintain a continuous, seamless presence, and even more were siphoned away from ground support as they were at Okinawa.42 The ability of the CAPs (combat air patrols) to actually maintain coverage of this area once battle was joined—the CAP checkpoints averaged fifteen miles apart over a clutter of cloud-covered peaks—proved to be extraordinarily difficult and broke down quickly. We didn't have enough depth. The CAPs were drawn away from the barrier patrol by the first Japs coming through. We had expected that there would be some leakers— possibly quite a few—but did not anticipate that they could successfully coordinate and launch as many aircraft as they did.”

“It sounds to me, sir,” observed his questioner, “that they had figured us out.

“It's clear that they'd developed plans based on a comprehensive understanding of the set-piece way in which we do business—our amphibious operations,” acknowledged the admiral, “and that their plans extended well beyond air operations. In fact, they were so confident in their analyses of our intentions that they moved a number of divisions into Kyushu before our airpower—our ability to interdict them—had been built up sufficiently on Okinawa. The Japs were one step ahead of us. Our intelligence noted the appearance of these reinforcements which, when combined with the units already there and the new divisions being raised from the island's massive population, presented us with an awful picture,43 but one that we could have dealt with if we had been able to get our forces ashore intact.

“There's an interesting footnote for future historians on this matter. Some of you may know that the original name of the Kyushu operation was Olympic, but do you know why the code name was changed? When intelligence discovered the rapid buildup, it was believed that the invasion plans may have somehow been compromised.44 The change from Olympic to Majestic represented an effort to confuse Japanese intelligence when, in fact, the changes were based on analyses conducted within Imperial headquarters. The Japanese had correctly deduced both the location and approximate times of both Majestic and Coronet45and decided to expend the bulk of their aircraft as kamikazes during the critical first ten days of each invasion. The landing forces themselves were to be the main focus of Japanese efforts, with additional aircraft allotted to keep the carrier task forces occupied.”46

More than a few of the officers present would have liked to be told how Turner knew this but knew better than to ask, and the next question returned to the kamikazes. It came from another former destroyer captain.

“Sir, irrespective of how many of our own aircraft were used for suppression of Nip bases and defense of the landing zones, it seems to me that the very large number and close proximity of their bases—and Kyushu's mountains—created virtually ideal conditions for the suiciders.”

“Yes. I've had a good deal of time to think about this. The Japanese had seven interrelated advantages during the defense of the home islands that they did not have at Okinawa.

“First, their aircraft were able to approach the invasion beaches from anywhere along a wide arc, thus negating any more victories along the line of the [Marianas] Turkey Shoot or the Kikai Jima air battles [north of Okinawa], where long distances required Jap aircraft to travel relatively predictable flight paths.

“Second, Kyushu's high mountains masked low-flying kamikazes from search radars, thus limiting our response time to incoming aircraft. Plans were made to establish radar sites within our lines and on the outlying islands as quickly as the tactical situation allowed, but this had only a minor effect on the central problem—the mountains. In addition, most shore-based radar units during Majestic were not slated to be operational until after X+1047—and by then the kamikaze attacks were drawing to a close.

“Third, we knew that the Japs were suffering from a severe shortage of radios, and some among us discounted their ability to coordinate attacks from dispersed airfields and hiding places through use of telephone lines. At this point in the war, however, Jap reliance on telephones was more a strength than a weakness. No communications intercepts there.48 Our forces could neither monitor nor jam the land lines and, like the Jap electrical system, it presented few good targets for air attack.

“The fourth advantage was related to the second and had to do with the virtually static nature of our assault vessels while conducting the invasion. Because the ships disembarking the landing force were operating at a known location, kamikazes didn't have to approach from a high altitude, which allowed them the visibility needed to search for far-flung carrier groups yet also made them visible to radar. Instead, they were able to approach the mass of transports and cargo ships from the mountains and then drop to very low altitudes. The final low-level run on the ships offered no radar, little visual warning, and limited the number of antiaircraft guns that could be brought to bear against them. It wasn't difficult to see that this was going to be a problem during Majestic, since a much larger percentage of kamikazes got through to their targets when flying under radar coverage to fixed locations, like Kerama Retto anchorage [Okinawa], than those approaching ships at sea from higher altitudes.

“I want to stress, however, that despite the advantages offered by radar picking up the high-fliers, ships operating at any fixed location invited concentrated attack, and the radar pickets near certain Japanese approach routes to Okinawa suffered much more than those on the move with fast carrier task forces. The lack of predictable approach routes at Kyushu only exacerbated the situation.

“Fifth, we had begun extensive use of destroyers as radar pickets as early as the Kwajalein operation in January 1944, and by the end of that year comparatively sophisticated CICs (combat information centers) were effectively providing tactical situation plotting and fighter direction from select destroyers. Unfortunately, coordination within and timely communications from the radar pickets' newly installed CICs presented a problem, with the centers frequently becoming overwhelmed by the speed of events and sheer quantity of bogies. Add a nearby landmass to the equation, and things got dicey in a hurry.

“Sixth, as previously noted radar coverage of the countless mountain passes was virtually nil during the Kyushu operation, and the 5th Fleet CAPs attempting to form a barrier halfway up the island were essentially on their own because they were frequently out of direct contact with the pickets assigned to control the checkpoints. The barrier patrol over the 120-mile-wide midsection of Kyushu and Amakusa-Shoto, an island close to the west, were able only to find and bounce a comparatively small percentage of attackers coming through the mountains, and this number shrank even further in areas with a modest amount of cloud cover. As it turned out, Majestic was launched at a time that the weather was ideal for Japanese purposes— and I might add the same would have been true for Coronet. Not only did the moderate-to-heavy cloud cover, ranging from 3,000 to 7,000 feet, tend to mask the low-level approach of aircraft to the landing beaches, but the inexperienced Jap pilots searching for carriers out to sea from high altitudes also found that these clouds provided good cover from radar-vectored CAPs while being no great hindrance to navigation.

“Last, and perhaps most important of all, a proportionately small number of suicide aircraft got through to the vulnerable transports off Okinawa because of the natural tendency of inexperienced pilots to dive on the first target they saw. As a result, the radar pickets had, in effect, soaked up the bulk of the kamikazes before they reached the landing area. Accomplishing this entailed terrible losses even though the destroyers had their own CAPs and were sometimes supported by LCSs and LSMs acting as gunboats. At Kyushu, however, there were no radar pickets on the landward side of the assault shipping to absorb the blows meant for the slow-moving troop transports and supply vessels, which had to lock themselves into relatively static positions offshore during landing operations. These were the ships that kamikaze pilots were specifically to target, and circumstance and terrain went a long way toward helping them achieve their goal of killing the largest number of Americans possible.

“While all this must seem like a wonderful example of twenty-twenty hindsight, I believe that we could have anticipated much more of this ahead of time if we had not been lulled by the lack of air opposition in the months preceding Majestic. It was simply inconceivable to many of us that they would be willing to take the degree of punishment that they did from the air without fighting back. It crossed few minds that they were, in effect, waiting to see the whites of our eyes. Next question.”

“Sir, wouldn't this also tie in with why we didn't disperse our blood supplies ahead of the invasion?”

The young captain's question touched on one of the most grim facets of the invasion. Five LST(H)s,49 one for each set of invasion beaches, had been outfitted as distribution centers for plasma and whole blood needed by the wounded ashore.50 Even before the first waves of landing craft hit the beaches, one had been turned into an inferno and another sunk by midmorning of X-Day. For many thousands of wounded ashore, this was a disaster of terrible proportions. The landing beaches now denied blood supplies had been unable to receive assistance from the remaining three vessels because of excessive casualties in those ships' own assigned areas. Although it was difficult to calculate precisely, estimates of the number of wounded whose deaths might have been prevented if the immediate blood supply had not been nearly halved ran as high as 4,100. Emergency shipments were rushed up by destroyer from Okinawa and flown direct to escort carriers off Kyushu aboard Avenger torpedo bombers from the central blood bank on Guam. These emergency shipments, together with blood donated by bone-tired sailors after the last air raids of the day, enabled the situation to be stabilized by X+4.

“The care and storage of blood products is a complicated matter. It is a valuable—and highly perishable—commodity that needs to be stored in and distributed from refrigeration units. The system for blood distribution at Kyushu made perfect sense in light of these requirements and past experience.51 The blood supply expert on MacArthur's staff had, in fact, pointed out the vulnerability of the system to be employed, but lack of proper facilities had rendered any worthwhile changes impossible on such short notice.”

Even Turner realized that his answer sounded like it had been written by a press officer, and he quickly moved on to the next question by pointing to an officer in the third row who had raised his hand twice before.

Deception Operations

“Sir, with all the ships we produced during the war, why didn't we create a dummy invasion fleet? Why didn't we make more of an effort to draw their planes out early so that we could get at them?”

The admiral did not answer immediately, but instead cast a glance at the poker face of Spruance, sitting to his left. Had the young captain thought of this himself or had he picked up on clues in the newspapers where references to an elaborate deception operation—not carried out—were already beginning to leak from an unannounced, closed-door session that Turner had with the Taft-Jenner committee? The room was deathly quiet as the admiral looked back to the podium and drew a deep breath. The men—the veterans—in the room deserved to get an answer.

“Certain deception operations were conceived ahead of Majestic,” he began.52 “Code-named Pastel, they were patterned after the very successful Bodyguard operations conducted against the Nazis before, and even well after, the Normandy invasion. Through those operations, very substantial German forces were held in check far from France in Norway and the Balkans, and a well-equipped army north of the invasion area was kept out of the fight until it was too late to intervene effectively.53 Deception operations of this type were particularly effective in Europe, with its extensive road and rail nets, but were a waste of time against Japan proper. They all assumed a strategic mobility that the Japanese did not possess for higher formations—corps and armies—and were made even less effective by our own air campaign against the home islands, which essentially froze those formations into place. Distant movements could only be made division by division and only at a pace that a soldier's own feet could carry him. Likewise, the success of the blockade rendered the deception operations against Formosa and the Shanghai area unnecessary.

“The Japanese, themselves, had realized this early on, and their system of defense call-up and training during the last year was reoriented toward raising, training, and fielding combat divisions locally in order to minimize lengthy overland movements.54 With major population centers within easy marching distance of threatened areas, they could actually get away with this. The most useful comparison to our own history might be the Minutemen.”

Turner could see that some of the students were questioning the relevance of his comments and were wondering if he was going to dodge the question altogether.

“In short,” he continued, “we spent far too much time and energy trying to keep the Japanese from doing something that both we and the Japs knew they couldn't do anyway. To the specifics of your question, in May of last year, I, along with Admirals Spruance and [Marc A.] Mitscher, were replaced by Bill Halsey and his crew so that we could begin planning for Kyushu. I regretted not being able to see Okinawa through to the finish, but Iceberg was to have been wrapped up in forty-five days, and since the 5th Fleet of Admiral Spruance had been selected to handle Kyushu, what was then called Olympic, planning could not be delayed any further.55

“Our work was conducted back at Guam and took full account of what we had learned at Okinawa. It was my conclusion that kamikaze attacks of sufficient strength might so disrupt the landings that a vigorous resistance ashore against our weakened forces would put our timetable for airfield construction in serious jeopardy. Four months was the minimum time judged necessary for base construction and subsequent softening up before our landings near Tokyo. These, in turn, had to be conducted before the spring monsoon season, when use of our armored divisions from Europe would become impossible on the Kanto, or Tokyo, Plain.56 The landing force had to get off to a running start, and it was up to us to get them there in the best possible shape. What we proposed was exactly what you suggested form a fleet—a dummy fleet carrying no men; no equipment—escorted by the usual screen but with the air groups rearranged to carry a preponderance of Hellcats and Corsairs.57

“It had to look credible, especially from the air. Feints at Okinawa, that we had considered quite impressive, had absolutely no discernible impact on the course of the campaign.58 Moreover, communications intelligence made it clear that the Japs were expecting us to try something like that again and we estimated that we would have to utilize 400 ships, not counting the escort, in order to provide enough mass to be convincing.59 Assault shipping and bombardment groups would form up at multiple invasion beaches. We would follow all normal procedures— heavy radio traffic, line of departure, massive bombardment. All of this would take time, of course, and the Japs would be able to get a real good look at us. They would judge it to be the real thing because it was—minus a half-million troops! They would send up thousands of aircraft to come after us and we would be able to concentrate virtually all of our airpower, by sectors running from Nagoya [south-central Honshu] through Kyushu, and we would knock them down. There would be leakers. We would lose ships and many good sailors. But at the end of the day—actually three days—we'd pull out.

“The Japs would undoubtedly believe that they had repelled the invasion. Those same ships and others, however, would be at Okinawa, at Luzon, at Guam, loading for the real knockout. We would be back at Kyushu in just two weeks and this time there would be so few meatballs left that we could handle them easily. Preparations for Operation Bugeye60 were begun in early June at Pearl [Harbor] and Guam.”

A slight pause in Turner's commentary precipitated a sea of hands raised across the floor. The Class of '47 was a sharp group, and it was not hard to guess what was on their minds.

Typhoon Louise Strikes

“Was it Louise,” asked one, “was it the October typhoon that killed the plan?”61

“Ultimately, yes. It had been a hard sell to begin with. The shipping crisis that had come to a head at Leyte62 had never been completely solved and there was a legitimate concern that if too much was lost during Bugeye we would be hard-pressed to fulfill our needs during Majestic. We received the go-ahead for Bugeye only after certain numbers of assault ships of every category had been pulled from the operation. Vessels like the thirty-eight to be used as blockships for Coronet's 'Mulberry' harbor63 would have been completely satisfactory for the feint, and yet though many were virtual derelicts, we were nevertheless required to preserve them for Tokyo. I need not remind you that construction of the artificial harbor carried a priority second only to development of the atom bomb,64 and that we were producing seven unique, heavy-lift salvage ships in two classes especially for the invasion.65 As things turned out, four of the six that had arrived in-theater survived Typhoon Louise and were fully employed with salvage operations at Okinawa till nearly Thanksgiving.

“Everyone in this room is painfully aware of the disaster at Okinawa. Every plane that could be gassed up was sent south [to Luzon] and most were saved. The flat bottoms [assault shipping and craft designed to be beached] weren't so lucky. Six-hours' warning was not enough. Shifting cargoes in the combat-loaded LSTs sent sixty-one of 972 LSTs to the bottom; 186 of 1,080 LCTs went down or were irretrievably damaged; 92 of 648 LCIs66—the list goes on.67 Plus a half-dozen Liberty ships and destroyers. At least they couldn't blame this one on Bill.68 This storm took on mystical proportions to the Japanese war leaders who had defied the Emperor and taken over the government when he tried to surrender during the first four atomic attacks in August.”69 Harkening back to the original “Divine Wind,” or kamikaze, that destroyed an invasion force heading for Japan in 1281, they saw it as proof that they had been right all along. Their industrial base in Manchuria was gone because of the Soviet invasion, their cities were in ashes, but the Japs were even more certain that we would sue for peace if they just held out.

“Any chance of carrying out the feint was gone. With a little more time, the shipping losses—greater in tonnage than Okinawa—could be made up. But there was no time. The Joint Chiefs originally set December 1, 1945, as the Kyushu invasion date with Coronet, Tokyo's Kanto Plain, three months later on March 1.

“What I'm about to say is an important point and I'll be returning to it in a moment. To lessen casualties, the launch of Coronet included two armored divisions shipped from Europe that were to sweep up the plain and cut off Tokyo before the monsoons turned it into vast pools of rice, muck, and water crisscrossed by elevated roads and dominated by rugged, well-defended foothills.

“Now, planners envisioned the construction of eleven airfields on Kyushu for the massed airpower which would soften up the Tokyo area. Bomb and fuel storage, roads, wharves, and base facilities would be needed to support those air groups, plus our 6th Army holding a 110-mile stop line one-third of the way up the island. All plans centered on construction of the minimum essential operating facilities, but most of the airfields for heavy bombers were not projected to be ready until ninety to 105 days after the initial landings on Kyushu,70 in spite of a massive effort. The constraints on the air campaign were so clear that when the Joint Chiefs set the target dates of the Kyushu and Tokyo invasions for December 1, 1945, and March 1, 1946, respectively, it was apparent that the three-month period would not be sufficient. Weather ultimately determined which operation to reschedule, because Coronet could not be moved back without moving it closer to the monsoons and thus risking serious restrictions on all ground movement— and particularly the armor's drive up the plain—from flooded fields, and the air campaign from cloud cover that almost doubles from early March to early April.71 MacArthur's air staff proposed bumping Majestic ahead by a month, and both my boss, Admiral Nimitz, and the Joint Chiefs immediately agreed. Majestic was moved forward one month to November 1. 72

“The October typhoon changed all that. A delay till December 10 for Kyushu, well past the initial—and unacceptable— target date was forced upon us, with the Tokyo operation pushed to April 1—dangerously close to the monsoons. We were going to get one run, and one run only, at the target. No Bugeye. One of the greatest opportunities of the war had been lost.”

At first there were no hands appearing above the audience since they were still absorbing everything that Admiral Turner had said. A navy captain in the second row was the first to break the silence.

“Sir, was there reconsideration at this time of switching to the blockade strategy that we, the navy, had been advocating since 1943?”

Turner's host that evening, Admiral Spruance, had been outspoken in his belief that such a move was the best course73 but, like Turner, had followed orders to the fullest of his ability and beyond. Turner knew that he had already said far more than he should on Bugeye and moved to wrap things up.

“I can't tell you what others were advocating. All I can say is that I was fully, very fully, engaged in carrying out my orders. On a personal note, I would have to say that I believe that the change in plans regarding the use of atom bombs during Majestic was fortuitous. After the first four bombs on cities failed in their strategic purpose of stampeding the Japanese government into an early surrender, the growing stockpile of atom bombs was held for use during the invasion. Initially, though, we did not intend to use them as they were eventually employed against Japanese formations moving down from northern Kyushu. Initially we were going to allot one to each corps zone shortly before the landings.”74

Audible gasps and a low whistle could be heard from some in the audience, who immediately recognized the implications of what the admiral was saying.

“Yes,” Turner acknowledged “the radiation casualties we suffered in central Kyushu were bad enough, but they were only a fraction of what would have happened if we had run a half-million men directly into radiated beachheads—and all that atomic dust being kicked up during the base development and airfields construction! The result hardly bears thinking about. It was clear, after the initial bombs in August, that the Japs were trying to wring the maximum political advantage from claims that the atom bombs were somehow more inhuman than the conventional attacks that had burnt out every city with a population over 30,000. At first their claims about massive radiation sickness were thought to be purely propaganda.75 However, over the next few months it was determined that there was enough truth to what they were saying to switch the bombs to targets of opportunity after the Jap forces from northern Kyushu moved down to attack our lodgment in the south. They had to concentrate before they could launch their counter-offensive, and that's when we hit 'em. As for the original landing zones, repeated carpet bombing by our heavies from Guam and Okinawa produced the same results that the atom bombs would have, and besides, the big bombers had essentially run out of strategic targets long before the invasion. The carpet bombing gave them something to do.” This remark elicited laughter.

“The Jap warlords were unmoved when atom bombs were employed over cities, but the extensive use of the bombs against their soldiers is what finally pushed them to the conference table. Yes, they changed their tune when they faced the possibility of losing their army without an 'honorable' fight, but so did we when it became undeniably clear that our replacement stream would not keep up with casualties.”

Turner looked over at General “Howlin' Mad” Smith, and continued “One man in this room tonight served in the trenches of World War One. An incomplete peace after that war meant that he and the sons of his buddies had to fight another war a generation later. We can only pray that the recent peace will not end in a bigger, bloodier, perhaps atomic, war with Imperial Japan in 1965. Thank you.”

The Reality

The coup attempt by Japanese forces unwilling to surrender was thwarted by Imperial forces loyal to Emperor Hirohito, and the Japanese government succeeded in effecting a formal surrender before the home islands were invaded. Occupation forces on Kyushu were stunned by the scale of the defenses found at the precise locations where the invasion was scheduled to take place. The U.S. military government eventually disposed of 12,735 Japanese aircraft.

On October 9-10, 1945, Typhoon Louise struck Okinawa. Luckily, Operation Majestic had been canceled months earlier. There was considerably less assault shipping on hand than if the invasion of Kyushu had been imminent, and “only” 145 vessels were sunk or damaged so severely that they were beyond salvage.

Bibliography

Asada, Sadao, “The Shock of the Atomic Bomb and Japan's Decision to Surrender—A Reconsideration,” Pacific Historical Review 67, November 1998.

Bartholomew, Charles A., Captain, USN, Mud, Muscle and Miracles: Marine Salvage in the United States Navy (Department of the Navy, Washington, D.C., 1990).

Bix, Herbert P., Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan (Harper Collins, New York, 2000), 519.

Bland Larry 1. (ed.), George C. Marshall Interviews and Reminiscences for Forrest C. Pogue (George C. Marshall Foundation, Lexington, 1996).

Brown, Anthony Cave, Bodyguard of Lies, vol. 2 (Harper & Row, New York, 1975).

Buell, Thomas B., The Quiet Warrior: A Biography of Admiral Raymond A. Spruance (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 1987).

The Campaigns of MacArthur in the Pacific, vol. 1: Reports of General MacArthur (General Headquarters, Supreme Allied Command, Pacific, Tokyo, 1950).

Cannon, M. Hamlin, Leyte: The Return to the Philippines (Department of the Army, Washington, DC, 1954).

Cline, Ray S., Washington Command Post: The Operations Division (Department of the Army, Washington, DC, 1954).

Coakley, Robert W, and Leighton, Richard M., The War Department: Global Logistics and Strategy, 1943-1944 (Department of the Army, Washington, DC, 1968).

Coox, Alvin D, “Japanese Military Intelligence in the Pacific: Its Non-Revolutionary Nature,” in The Intelligence Revolution: A Historical Perspective (Office of Air Force History, Washington, D.C., 1991).

, “Needless Fear: The Compromise of U.S. Plans to Invade Japan in 1945,” Journal of Military History, April 2000.

Drea, Edward J., MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942-45 (University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, 1992).

Dyer, George Carroll, Vice Admiral, USN, The Amphibians Came to Conquer: The Story of Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner (U.S. Navy Department, Washington, D.C, 1972).

Frank, Bemis M., and Shaw, Henry I., Jr., History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, vol. 5: Victory and Occupation (Historical Branch, U.S. Marine Corps, Washington, DC, 1968).

Gallicchio, Marc, “After Nagasaki: General Marshall's Plan for Tactical Nuclear Weapons in Japan,” Prologue 23, Winter 1991.

Giangreco, D. M., “Operation Downfall: The Devil Was in the Details,” Joint Force Quarterly, Autumn 1995.

, “The Truth About Kamikazes,” Naval History, May-June 1997.

, “Casualty Projections for the Invasion of Japan, 1945-1946: Planning and Policy Implications,” Journal of Military History, July 1997.

Hattendorf, John B.; Simpson, B. Michael, III; and Wadleigh, John R., Sailors and Scholars: The Centennial History of the Naval War College (Naval War College Press, Newport, Rhode Island, 1984).

Hattori, Colonel, The Complete History of the Greater East Asia War (500th Military Intelligence Group, Tokyo, 1954).

Huber, Thomas M., Pastel: Deception in the Invasion of Japan (Combat Studies Institute, Fort Leavenworth, 1988).

Inoguchi, Rikihei, Captain, UN, and Nakajima, Tadashi, Commander, UN, The Divine Wind: Japan's Kamikaze Force in World War II (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 1958).

Interrogations of Japanese Officials, vol. 2 (United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Tokyo, 1946).

“The Japanese System of Defense Call-up,” Military Research Bulletin,no. 19, 18 July 1945.

Kendrick, Douglas B., Brigadier General, USA, Medical Department,United States Army: Blood Program in World War II (Office of the Surgeon General, Washington, DC, 1964).

Morison, Samuel Eliot, Rear Admiral, USN, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 12: Leyte, June 1944–January 1945 (Little, Brown, Boston, 1958).

, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 13, The Liberation of the Philippines: Luzon, Mindanao, the Visayas, 1944–1945 (Little, Brown, Boston, 1959).

, History of the United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 14: Victory in the Pacific, 1945 (Little, Brown, Boston, 1960).

, The Two Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War (Little, Brown, Boston, 1958).

Oil in Japan's War: Report of the Oil and Chemical Division, United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Pacific (United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Tokyo, 1946).

O'Neill, Richard, Suicide Squads: Axis and Allied Special Attack Weapons of World War II, Their Development and Their Missions (Ballantine Books, New York, 1984).

Potter, E.B., Nimitz (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 1976).

Roland, Buford, Lieutenant Commander, USNR, and Boyd, William B., Lieutenant, USNR, U.S. Navy Bureau of Ordnance in World War II (U.S. Navy Department, Washington, DC, 1955).

Sakai, Saburo; Caidin, Martin; and Saito, Fred, Samurai (Bantam Books, New York, 1978).

Sherrod, Robert, History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II (Presidio Press, Bonita, 1980).

Stanton, Shelby L., Order of Battle, U.S. Army, World War II (Presidio Press, Novate, 1984).

Walker, Lewis M., Commander, USNR, “Deception Plan for Operation Olympic,” Parameters, Spring 1995.

Notes

1. Vice Admiral George Carroll Dyer, USN, The Amphibians Came to Conquer: The Story of Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner (U.S. Navy Department, Washington, DC, 1972), 1109.

2. John B. Hattendorf, B. Michael Simpson III, and John R. Wadleigh, Sailors and Scholars: The Centennial History of the Naval War College (Naval War College Press, Newport, Rhode Island, 1984), 329.

3. Dyer, op.cit., 1118–19.

4. Ibid., 1117.

5. The Joint Chiefs of Staff designated the invasion of Kyushu (Operation Olympic, later Majestic) as X-Day, December 1, 1945, and the invasion of Honshu (Operation Coronet) as Y-Day, March 1, 1946.

6. Thomas B. Buell, The Quiet Warrior: A Biography of Admiral Raymond A. Spruance (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 1987), 417–18.

7. Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison, USN, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 12: Leyte, June 1944–January 1945 (Little, Brown, Boston, 1958), 300–306,339–49,354–60, 366–68, 380–85.

8. M. Hamlin Cannon, Leyte: The Return to the Philippines, in the series The United States Army in World War II (hereafter USAWWII) (Department of the Army, Washington, DC, 1954), 8–9. See also Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison, USN, The Two Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War (Little, Brown, Boston, 1958), 422–23.

9. Cannon, op.cit., 306.

10. Ibid., 294–305.

11. Shelby L. Stanton, Order of Battle. U.S. Army, World War II (Presidio Press, Novate, 1984), 112–13.

12. Cannon, op.cit. 92–94, 99–102.

13. Ibid, 306–308.

14. Ibid, 365–67.

15. Operations of U.S. aircraft as recent as the Gulf War's “Scud hunt” illustrate that this is generally not as easy as some presume it to be.

16. Hattori Takushiro gives the number of Japanese airfields on the home islands, including those under construction and ninety-five concealed airfields, at 325. Figures from the July 13, 1945, “Central Agreement Concerning Air Attacks,” between the Japanese army and navy in vol. 4 of Colonel Hattori's The Complete History of the Greater East Asia War (500th Military Intelligence Group, Tokyo, 1954), 165. Translated from Hattori's Daitoa Senso zenshi, 4 vols. (Masu Shobo, Tokyo, 1953).

17. Ibid., vol. 4, 234. Hattori states that the blow destroyed fifty-eight navy and two army aircraft on the ground. Smoke and decoys prevented an accurate U.S. assessment, and Morison calls it “indeterminate” in History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 14: Victory in the Pacific, 1945 (Little, Brown, Boston, 1960), 100.

18. Oil in Japan's War: Report of the Oil and Chemical Division, United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Pacific [hereafter USSBS] (Tokyo, 1946), 87–89; and Hattori, op.cit., vol. 4, 165.

19. See Captain Rikihei Inoguchi, UN, and Commander Tadashi Nakajima, UN, The Divine Wind: Japan s Kamikaze Force in World War II (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 1958), 81–82, for an examination of high-grade decoy production and employment at an austere facility. The quality of dummy aircraft construction varied considerably from location to location, but even simple constructions of straw and fabric were effective since pilots under fire in speeding fighters had little time to closely examine aircraft on the ground.

20. U.S. estimates in May 1945 that 6,700 aircraft could be made available in stages, grew to only 7,200 by the time of the surrender. This number, however, turned out to be short by some 3,300 in light of the armada of 10,500 planes the enemy planned to expend in stages during the opening phases of the invasion operations—most as kamikazes. After the war, occupation authorities discovered that the number of military aircraft actually available in the home islands was over 12,700. See MacArthur in Japan: The Occupation: Military Phase, vol. 1: Supplement, Reports of General MacArthur (General Headquarters, Supreme Allied Command, Pacific, Tokyo, 1950), 136; and Hattori, op.cit., vol. 4, 174.

21. Aid., vol. 4, 191. Transports had always been a high priority for suicide aircraft but did not become the main focus of Japanese planning until the spring and summer of 1945. See Interrogations of Japanese Officials, vol. 2 (USSBS Naval Analysis Division, Tokyo, 1946), Admiral Soemu Toyoda, 318; Vice Admiral Shigeru Fukudome, 504.

22. Inoguchi and Nakajima, op.cit., 25–26.

23. Saburo Sakai with Martin Caidin and Fred Saito, Samurai (Bantam Books, New York, 1978), 254–56, 263.

24. Inoguchi and Nakajima, op.cit. 58–59, Sakai, op.cit. 294–95.

25. From Jack Moore, in D. M. Giangreco, “The Truth About Kamikazes,” Naval History, May–June 1997, 28.

26. COMINCH P-0011, Anti-Suicide Action Summary, August 21, 1945, 20.

27. Lieutenant Commander Buford Roland, USNR, and Lieutenant William B. Boyd, USNR, U.S. Navy Bureau of Ordnance in World War II (U.S. Navy Department, Washington, DC, 1955), 245–47.

28. Aid., 267-68.

29. Anti-Suicide Action Summary, 21. See also Confidential Information Bulletin no. 29, Anti-Aircraft Action Summary, World War II (COMINCH, October 1945) for an overview of gun, ammunition, and fire control development.

30. Inoguchi, op.cit., 85–91.

31. From a March 25, 1945, combat report of the Fletcher Class destroyer USS Kimberly, DD-521, excerpted in Richard O'Neill's Suicide Squads: Axis and Allied Special Attack Weapons of World War II, Their Development and Their Missions (Ballantine Books, New York, 1984), 164–65.

32. A miniature radio device that automatically exploded projectiles when they passed close to their targets.

33. Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison, USN, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 13: The Liberation of the Philippines: Luzon, Mindanao, the Visayas, 1944–1945 (Little, Brown, Boston, 1959), 58.

34. A useful window to the thinking of some senior members of Nimitz's staff can be found in Joint Staff Study, OLYMPIC, Naval and Amphibious Operations, CINCPAC, 5, produced under the direction of Admiral Forrest Sherman, Deputy Chief of Staff, COMINCH. Updated through at least July 8, 1945, it echoes the intelligence reports referred to in this comment and states that attacks by U.S. forces “will have served to reduce the enemy air force to a relatively low state” by the projected November 1 invasion. However, the assessment in Staff Study, Operations, CORONET, General Headquarters USAFP, August 15, 1945, demonstrates a detailed understanding of Japanese plans for employment of kamikaze aircraft.

35. Oil in Japan's War. USSBS, 40–41.

36. Interrogations of Japanese Officials, vol. 2, USSBS. Vice Admiral Shigeru Fukudome, 508.

37. Oil in Japan s War, USSBS, 68, 88.

38. Hattori, op.cit. vol. 4, 166.

39. Joint Staff Study, OLYMPIC, Naval and Amphibious Operations, CINCPAC, May 1945, Annex 1 to Appendix C, June 18, 1945; and Staff Study, Operations, OLYMPIC, General Headquarters USAFP, April 23, 1945, 13 and map 8.

40. Ibid., Joint Staff Study, Olympic.

41. See CINCPAC map “Appendix 35, Provisional Layout of Fighter Defense,” in Report on Operation “OLYMPIC” and Japanese Counter-Measures, part 4, Appendices by the British Combined Observers (Pacific), Combined Operations Headquarters, August 1, 1946.

42. Bemis M. Frank and Henry I. Shaw, Jr., History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, vol. 5: Victory and Occupation (Historical Branch, U.S. Marine Corps, Washington, DC, 1968), 187, 671; and Robert Sherrod, History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II (Presidio Press, Bonita, 1980), 385–86. Marine ground support sorties at Okinawa amounted only to 704 of the 4,841 launched between April 7 and May 3, as protection of the escort carriers and the landing/support areas from kamikazes remained the top priority.

43. See “Amendment No. 1 to G-2 Estimate of Enemy Situation with Respect to Kyushu,” G-2, AFPAC, July 19, 1945, in The Campaigns of MacArthur in the Pacific vol. I: Reports of General MacArthur (General Headquarters, Supreme Allied Command, Pacific, Tokyo, 1950), 414–18; and Edward J. Drea, MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942–45 (University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, 1992), 202–25.

44. A comprehensive and insightful treatment of this subject was produced by Alvin D. Coox shortly before his death. See “Needless Fear: The Compromise of U.S. Plans to Invade Japan in 1945,” Journal of Military History, April 2000,411–38.

45. Ibid.; see also Hattori, op.cit., vol. 4, 185–87; and Coox, “Japanese Military Intelligence in the Pacific: Its Non-Revolutionary Nature,” in The Intelligence Revolution: A Historical Perspective (Office of Air Force History, Washington, DC, 1991), 200.

46. Hattori, op.cit., vol. 4, 171–74, 183, 191.

47. See CINCPAC map “Appendix 36, Radar Build Up,” in Report on Operation “OLYMPIC “ and Japanese Counter-Measures, part 4.

48.There are no circumstances in which Admiral Turner would even mention, let alone address in detail, U.S. codebreaking of Japanese radio transmissions other than to use the very general term “communications intelligence,” which includes a variety of methods for divining an enemy's intentions. See Drea, op.cit.

49. The H designation stands for hospital. These were tank landing ships converted to serve as forward medical and evacuation facilities.

50. Brigadier General Douglas B. Kendrick, USA, Medical Department. United States Army: Blood Program in World War II (Office of the Surgeon General, Washington, D.C., 1964), 639–41.

51. Ibid., 633–39.

52. Thomas M. Huber, Pastel: Deception in the Invasion of Japan (Combat Studies Institute, Fort Leavenworth, 1988).

53. Anthony Cave Brown, Bodyguard of Lies, vol. 2 (Harper & Row, New York, 1975), especially 900 and 904.

54. “The Japanese System of Defense Call-up,” Military Research Bulletin, no. 19, July 18, 1945, 1–3; and “Amendment No. 1 to G-2 Estimate of Enemy Situation with Respect to Kyushu,” G-2, AFPAC, July 29, 1945.

55. Admiral Nimitz was also worried that the strain of extended combat operations might be taking a toll on senior 5th Fleet commanders. For Nimitz's worries about fatigue, see Buell, op.cit., 391–93. Whether or not such fears were justified biographer E. B. Potter states categorically in Nimitz (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 1976), 456, that they were the cause of the reliefs.

56. D. M. Giangreco, “Operation Downfall: The Devil Was in the Details,” Joint Force Quarterly, Autumn 1995, 86–94.

57. Commander Lewis M. Walker, USNR, “Deception Plan for Operation OLYMPIC,” Parameters, Spring 1995, 116–57, for all references from “400 ships” through the following paragraph.

58. Hattori, op.cit., vol. 4, 124; Frank and Shaw, op.cit., 51, 107.

59. Walker, op.cit., 116–117.

*60. “Bugeye” is a fictitious name.

61. On October 9, 1945, a typhoon packing 140 mph winds struck Okinawa. This key staging area would have been expanded to capacity by that date if the war had not ended in September. Even at this late date, the area was still crammed with aircraft and assault shipping—much of which was destroyed. U.S. analysts at the scene matter-of-factly reported that the storm would have caused up to a forty-five-day delay in the invasion of Kyushu. For a review of the damage see Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison, USN, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 15: Supplement and General Index (Little, Brown, Boston, 1962), 14–17.

62. Robert W. Coakley and Richard M. Leighton, The War Department:Global Logistics and Strategy, 1943–1944 In USAWWII (Department of the Army, Washington, DC, 1968), 551–62; and Cannon, op.cit., 6-7, 34, 38, 276.

63. Staff Study, Operations, CORONET, General Headquarters USAFP, August 15, 1945, Annex 4, Basic Logistic Plan, Appendix H.

64. Ray S. Cline, Washington Command Post: The Operations Division, in USAWWII (Department of the Army, Washington, DC, 1954), 348.

65. Captain Charles A. Bartholomew, USN, Mud, Muscle and Miracles: Marine Salvage in the United States Navy (Department of the Navy, Washington, DC, 1990), 449–51.

66. LST, tank landing ship, 1,625 tons; LCT, tank landing craft, 143 tons; LCI, infantry landing craft, 209 tons; LCS (referred to elsewhere), 246 tons.

67. Assault shipping totals from Dyer, op.cit., 1105. See also Morison, Supplement, 14–17.

68. Reference to a pair of earlier typhoons that had severely damaged fleet elements under Admiral Halsey's command. The December 18, 1944, typhoon had capsized three destroyers and heavily mauled seven other ships. Nearly 800 lives had been lost and 186 planes were jettisoned, blown overboard, or irreparably damaged. The June 5, 1945, typhoon wrenched 130 feet of bow off a heavy cruiser; heavily damaged thirty-two other ships, including one escort and two fleet carriers that lost great lengths of their flight decks; and resulted in the loss of 142 aircraft. Totals from E. B. Potter, op.cit., 423, 456.

69. The coup attempt by officers intent on pursuing the war has been recounted in numerous works, but the original document upon which these accounts are based is Japanese Operations in the Southwest Pacific War, vol. 2, part 2: Reports of General MacArthur, 731–40. See also Sadao Asada, “The Shock of the Atomic Bomb and Japan's Decision to Surrender—A Reconsideration,” Pacific Historical Review 67, November 1998, 477–512, especially 592–95 on the insistence by mid-level and senior Japanese officers that the war be continued at all costs. For a different opinion see Herbert P. Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan (Harper Collins, New York, 2000), 519.

70. See CINCPAC chart “Appendix 43, Air Base Development,” in Report on Operation “OLYMPIC” and Japanese Counter-Measures, part 4; see also Staff Study, Operations, CORONET, annex 4, appendix C.

71. G-2 Estimate of the Enemy Situation with Respect to an Operation Against the Tokyo (Kwanto) Plain of Honshu, General Headquarters USAFP, G-2 General Staff, May 31, 1945, section 1–2, 1.

72. Reports of General MacArthur, vol. 1,399.

73. Buell, op.cit. 394–6, and Dyer, op.cit., 1108.

74. Larry I. Bland (ed.), George C. Marshall Interviews and Reminiscences for Forrest C. Pogue (George C. Marshall Foundation, Lexington, 1996), 424; and Marc Gallicchio, “After Nagasaki: General Marshall's Plan for Tactical Nuclear Weapons in Japan,” Prologue 23, Winter 1991, 396–404. See also D. M. Giangreco, “Casualty Projections for the Invasion of Japan, 1945–1946: Planning and Policy Implications,” Journal of Military History, July 1997, 521–82, especially 574–81.

75. 2605, section 3, Japanese Propaganda Efforts, Headquarters United States Army Forces Middle Pacific, November 1, 1945, 70–71.