CHAPTER 5

Why Financing Matters (Massey Ferguson)

This chapter discusses how firms make financing decisions—that is, how firms raise capital. It is meant to be at the level of an “issue spotter” discussion rather than answering the question in detail. We begin with an overview of the topic. In later chapters, we will detail how financing decisions are made. This chapter demonstrates that how a firm should finance itself is not answered merely by choosing the cheapest method possible. We illustrate our discussion with the situation faced by Massey Ferguson (Massey) in the early 1980s.

PRODUCT MARKET POSITION AND STRATEGY

Your authors have a strong belief that you cannot undertake corporate finance without first understanding a firm's product market position—that is, its product, its industry, its competitors, its advantages and disadvantages, its product market strategy, and so on.

Good corporate finance always begins with the product market. Massey was a manufacturer of agricultural equipment such as tractors, combines, harvesters, and so on. Although based in Canada, it was an international concern and sold its product throughout the world. At the time of our investigation in 1980, the firm's main competitors were International Harvester (Harvester) and John Deere (Deere).

Farm equipment is large, complicated, and expensive machinery. A farmer in North America will spend multiple hours a day in their combine plowing, seeding, and harvesting. Combines are enclosed vehicles that often have many amenities—such as air conditioning, stereos, and mini fridges—and can cost, in today's terms, upwards of $300,000.1 The products are not commodities, and there is some brand loyalty.

Massey did not target the large, high-end North American part of the farm equipment market. Of the three major farm equipment firms, Massey is the only one focused on smaller tractors and combines. The firm's tractors are manufactured in Canada and the UK but sold throughout the world. Massey's product market strategy evolved from their product market line in small tractors: Massey did not compete directly in North America with Deere and Harvester because they did not have the larger tractors desired by most of the North American market. To develop such a product line would have required an enormous investment in design, manufacturing, and distribution.

Therefore, Massey's product line and strategy were well matched. They produced small tractors and sold them to countries with small farms—primarily Asia and Africa. In this way, Massey avoided direct competition with its larger rivals, Harvester and Deere. By contrast, Deere produces primarily in North America and sells primarily in North America.

Let's ask the following questions: Why is Massey producing in Canada and the UK (developed countries) and selling to Asia and Africa (less developed countries)? Isn't a firm supposed to produce in low-cost countries and sell in high-cost countries? Why not produce all over the world if you are selling all over the world? Or stated another way, why is production concentrated while sales are dispersed?

POLITICAL RISK AND ECONOMIES OF SCALE IN PRODUCTION

Imagine you are the CEO of Massey and you are speaking before a meeting of security analysts (today this would take place via a conference call, but it used to be done in face-to-face meetings). How do you justify your strategy of concentrated production in high-cost countries and sales to the developing world? As CEO, you respond by asking the following questions: Where is the growth of agriculture in the world? Is it in the United States? What is happening to the number of farmers in the United States? Every year the number of farmers in the United States has declined—as the number of employees at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) continues to go up. Thus one day, every U.S. farmer may have their own USDA employee to bring them iced tea in the field. In a more serious vein, while the number of U.S. farmers and acreage under cultivation is going down during this period, in the rest of the world there is a green revolution, and a subsequent growth of agriculture.

So what is Massey's argument? Massey is positioned to go where the growth is.

Massey operates in more than 30 different countries around the world and is therefore diversified. Deere, on the other hand, is dependent on what happens in North America.2

In one light, Massey looks risky; in another, the firm appears safe because it is diversified. This argument is the same one made by Walter Wriston—CEO of Citibank when it was the world's largest bank—during a meeting with security analysts at about the same time: Citibank lent to the developing world because that's where the growth was.

Contrast two firms in the same industry: Deere builds large tractors in North America and sells primarily to large firms in North America. Massey builds small tractors in Canada and sells them to small farmers throughout the world because of production economies. Who has the riskier strategy? Probably Massey, but it is not a bad strategy, and it is one Massey can easily justify.

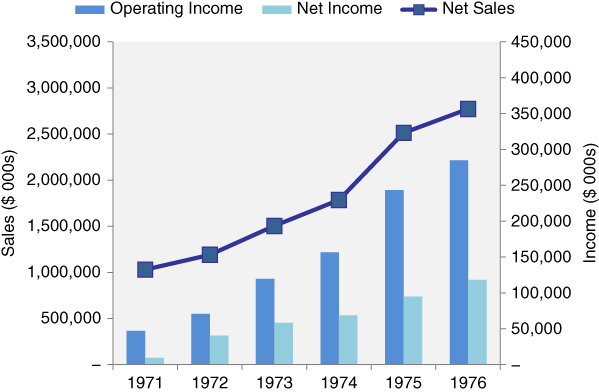

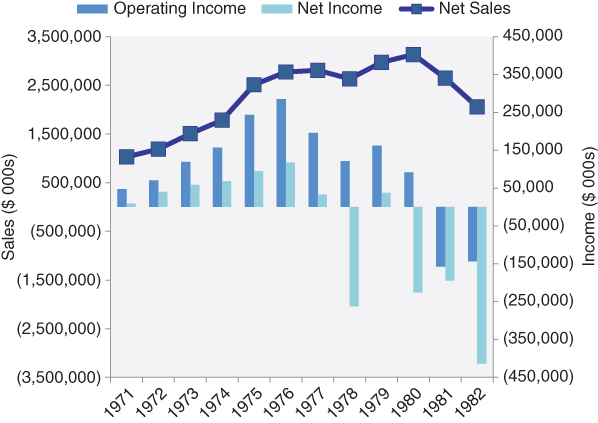

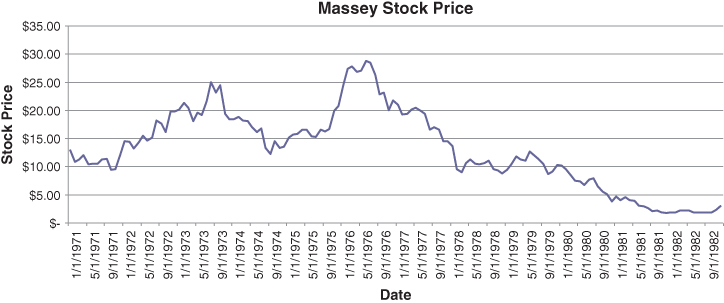

So is Massey's strategy working? How is the firm doing? Using Massey's financial statements in Appendix 5A, and looking first at sales for the period 1971–1976, they almost tripled in size (increasing 269%). Sales growth averaged 20% a year during this period, and ROE averaged 12.7% (increasing from a low of 2.4% in 1971 to 18.4% in 1976). Thus, Massey achieved good ROEs, with 22% sales growth during a period when they were trying to develop new markets. That is, they were trying to break into new markets, build infrastructure, and set up dealerships and distribution teams, but still grew at 22% a year with a 12.7% ROE. This is good performance. Massey's product market strategy may have been somewhat risky, but it was justifiable, and the financial results were good. They were basically going where the competition wasn't. (See Figure 5.1.)

FIGURE 5.1 Massey, 1971–1976

What is Massey's alternative strategy? They can compete in North America against Harvester and Deere in the market for large combines. That is, they can develop new large combines to compete. Alternatively, Massey can use the tractors they already produce and sell them in the developing world. Which strategy is riskier? Standing in the field in front of Harvester and Deere's combines, or going where Harvester and Deere aren't. This is, of course, only a quick synopsis.

MASSEY FERGUSON, 1971–1976

So how did Massey finance itself during the period 1971–1976? With debt (as can be seen in Appendix 5A, which provides Massey's Income Statements, Balance Sheets, and selected ratios for 1971–1982). Massey's debt/total capital (debt/(debt + equity)) averaged 47% between 1971 and 1976, and the firm's target debt ratio appears to be in the range of 41–51%. What about the other firms Massey competed with? Harvester was at 35.1%, and Deere's debt level was at 31.3% debt (and most of Deere's debt was AA rated)3 in 1976 (see Table 5.1).

TABLE 5.1 A Comparison of Massey to its Major Competitors in 1976

| Massey Ferguson | International Harvester | John Deere | |

| Debt/(debt + equity) | 46.9% | 35.1% | 31.3% |

| Interest coverage | 3.9 times | 2.8 times | 7.7 times |

| Moody's rating | Not Rated | Baa to A | A to AA |

Next let's consider the product market risk of this industry, which we will call here and in later chapters basic business risk (BBR). The farm equipment business is risky because demand is cyclical; that is, it fluctuates with the business cycle. Why does demand fluctuate? Because purchasing a tractor is deferrable, just as it is for most capital equipment. If farmers have a bad year, they will fix their current tractor rather than purchase a new one. You do the same thing: if you have an old car that does not run well, but you are in graduate school and have limited funds, you may continue repairing your car and postpone replacing it until you graduate. Likewise, a farmer will postpone buying a new tractor in bad times.

The demand for farm equipment is also highly interest-rate sensitive. When interest rates go up, sales go down. Why the inverse relationship? Because customers are not buying equipment with cash on hand; they are financing it. As interest rates increase, the financing costs to consumers become more expensive and have a negative impact on demand. At the same time, if interest rates rise, Massey's financing costs may rise. If Massey had borrowed at fixed rates, then there is no impact. However, examining Appendix 5A, we see that Massey has heavily utilized bank debt, which has variable interest rates. Therefore, as interest rates rise, Massey's sales should decline while Massey's interest costs go up. Thus, in a cyclical industry with deferrable sales that are highly interest-rate sensitive, Massey did nothing to mitigate its risk and, in fact, exacerbated it with bank debt.

In addition to these risks, Massey is selling to the developing world. These markets are embryonic, and growth is uncertain. There is potential political risk and exchange-rate risk as well. In addition, there is the potential for logistical problems because Massey is producing in the UK and Canada, and shipping around the world. Thus, Massey is in a risky cyclical business, and in addition it is pursuing the riskiest part of the global market for farm equipment.

Given the product market risk, why is Massey financing itself with debt? Remember, Massey is using financing in order to grow. Sales are growing at an average 22% a year, and ROE is an average of 12.7% a year. Going back to the PIPES case (Chapter 2), this means that Massey is growing faster than its sustainable growth rate. We define sustainable growth as:

As a result, Massey has to finance the difference to maintain its growth. Massey's choice is to finance with equity, to finance with debt, or to grow more slowly.

Should Massey grow more slowly? It's counter to Massey's product market strategy. Massey decided to target the developing world to penetrate these markets and become the industry leader there. If it grows more slowly, another firm may enter these markets and compete against it.

Why doesn't Massey issue equity? The reason is related to the control of the firm. At this point in time, Massey is controlled by its largest stockholder, an investment firm named Argus. And who controls Argus? Conrad Black.4 In essence, Conrad Black has decided he does not want to dilute Argus's 16% ownership of Massey, which means Massey cannot issue equity.

This means Massey is at an impasse. If it is growing at 22% a year and their ROE is only 12.7% before dividends, they must slow growth, issue equity, or borrow. Growing more slowly is counter to their product market strategy, and issuing equity is counter to their largest shareholder's desires, so borrowing debt is their only option.

SUSTAINABLE GROWTH

| The Corporate Balance Sheet | |

| Assets | Liabilities and Net Worth |

| Current Assets | Current Debt |

| Long-Term Assets | Long-Term Debt |

| Owner-Provided Funding | |

Let's look at a T account representing a Balance Sheet, with the left side of the T representing the assets (the resources the firm owns and controls) and the right side of the T representing the liabilities and net worth (how the resources were financed). Assume sales grow at 22% a year, and assume that the firm keeps the sales/asset ratio constant. This ratio, sales/assets, is also called capital intensity or asset turnover. Having a constant capital intensity ratio means that a firm will have the same number of sales per dollar of assets. Therefore, if sales grow at 22% a year, then assets also grow at 22% a year.

Now, if assets grow at 22% a year, what do liabilities and net worth grow at? Also 22%. This is not magic. If you want to keep the Balance Sheet in balance and capital intensity the same, if sales grow at 22% and assets grow at 22%, then liabilities and net worth must also grow at 22%.

Next, suppose we also keep the firm's leverage, measured as debt/equity,5 constant. If the ratio of liabilities to net worth is constant and liabilities grow at 22%, then net worth must also grow at 22%. However, what is Massey's ROE here? 12.7%. Now, if ROE is growing at 12.7%, then the maximum rate net worth can grow internally is 12.7%. The rate is less than that if the firm has a dividend payout. A firm's sustainable growth rate is therefore defined as:

To grow assets at 22%, faster than the sustainable growth rate of 12.7% (with no dividends), what must Massey do? Massey must either issue outside equity so that net worth can increase by more than 12.7%, or it must increase its liabilities by more than 22%. The latter also increases its debt/equity ratio. That is, if the firm's assets are growing faster than the firm's sustainable growth rate and the firm does not issue outside equity, then debt has to grow faster than the assets grow. This is necessary to keep our Balance Sheet balanced and is the reason why Massey has amassed so much debt and has such a high debt/equity ratio.

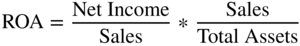

Currently we have used two ratios: capital intensity (sales to assets) and leverage (liabilities to net worth) in our discussion of sustainable growth. Let's now add a third ratio: profitability, which we define as profit to sales.6 Profit/sales is how much profit the firm gets for each dollar of sales. Note that sales/assets times profits/sales is equal to profits/assets, which is the return on assets (ROA).

Multiplying all three ratios together gives us the following equation, known as the DuPont Formula:

Which can be stated in words as:

The DuPont Formula was first used by the DuPont Corporation back in the 1920s. It is very important and is sometimes called the DuPont Model. The DuPont Formula says that a firm's return on equity (ROE) is the product of its profitability (profit/sales) times its capital intensity (sales/total assets) times its leverage (total assets/equity). If a firm wants to increase ROE, it can do so by one of these three levers: it can increase its profitability, its sales to assets, or its liabilities to net worth. Thus, holding profitability and capital intensity constant, a firm can increase its ROE by increasing its leverage.

The DuPont Formula is also central to understanding sustainable growth. Sustainable growth, as noted above, is the rate at which a firm can grow internally, that is, without outside financing. It assumes that the other ratios in the DuPont Model stay constant. That is, holding all else constant, if Massey grows faster than its sustainable growth rate, then it must use outside financing, either debt or equity.

To review, Massey is in the following situation in the period 1971–1976: it is growing quickly at 22% per year and have an average ROE of 12.8%. In addition, Massey doesn't want to issue outside equity in order to finance its growth. It therefore must finance with debt.

THE PERIOD AFTER 1976

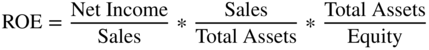

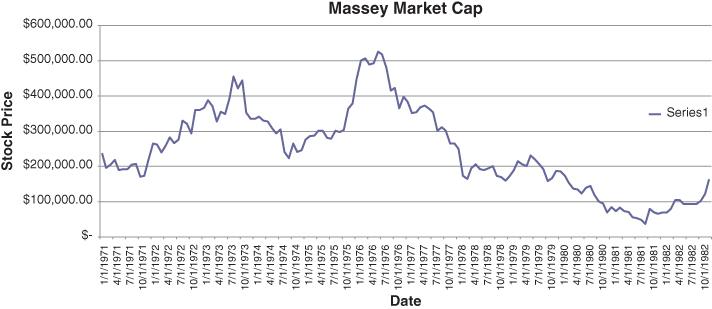

In this period, Massey's sales and financial performance declined dramatically, as seen in Figure 5.2.

FIGURE 5.2 Massey's Performance, 1971–1982

What went wrong? Many factors affected demand for farm equipment, leading to a decline in Massey's worldwide sales. Latin America experienced monetary restrictions, which meant that credit tightened and Massey's sales declined there. Europe experienced bad weather, hurting farm profitability and causing farmers to delay equipment purchases. In January 1980, the United States imposed a grain embargo on farm shipments to the Soviet Union, which lowered income to U.S. farmers and thus U.S. demand for farm equipment. In addition to the lower exports, North America suffered a recession (1980–1982). Thus, Latin America, Europe, and the United States all experienced a reduction in demand for farm equipment. Global interest rates increased at the same time, cutting demand further. Finally, foreign exchange rates moved against Massey. In particular, the British pound became more expensive as oil production in the North Sea increased (peaking in the early 1980s), so Massey's products produced in the UK suddenly became more expensive around the world.

In addition, there were political changes in some of the countries Massey sold to. Libya had a change in government when Muammar Gaddafi came to power (1969). In Iran, Massey stopped dealing with the Shah and began dealing with the Ayatollah (1979). All these changes mean that, at a minimum, Massey probably had to change their sales representatives. Thus, in addition to weather, credit restrictions, interest rate increases, and currency movements, Massey also faced political risk, all of which affected demand. Basically, everything that could go wrong did go wrong.

What is Massey's response to all this? It cut back their work force by a third; it closed plants; it sold assets; it lowered inventory; and it cut its dividends.7 Massey did all the things a firm does in a downturn. Perhaps it should have done these things sooner, but a more important question is: Did these actions work?

As shown in Appendix 5A, Massey's 1977 inventory-to-sales ratio is 40.5%, and by 1980 Massey reduced it to 31.6%. This is an enormous reduction. Net fixed assets to sales also declined from 21.2% to 15.6%. This means that Massey is now generating more sales per dollar of inventory and more sales per dollar of fixed assets. However, Massey's total assets to sales only went from 92.5% to 90.4%. This is because, at the same time, Massey's accounts receivable to sales increased from 19.3% to 30.9%.

Thus, Massey lays off employees, closes plants, sells assets, reduces inventory, reduces fixed assets, and what happens? Total assets to sales barely changes. Why? Receivables went up significantly. Why did receivables go up so much? Massey's customers are unable to pay. More specifically, in North America they are unable to pay Massey's dealerships. Massey sells much of its product line through dealers, and Massey partially finances its dealerships, which are now hanging on for dear life. Since farmers can't pay the dealerships, the dealerships are being kept alive by Massey. In fact, many of Massey's dealers went out of business. In North America, an estimated 50% of farm equipment dealers went out of business in the early 1980s.8

As a result of all this, Massey is posting losses. Losses are $225 million in 1980 alone. What is causing the losses? As mentioned above, the decline in demand and the failure to cut costs are contributing factors. Another major reason for Massey's losses is the firm's interest costs. In 1980 alone, interest on Massey's long- and short-term debt was $301 million.

Time out. Let this sink in for a second. In 1980 Massey has a loss for the entire firm of $225 million. Its interest costs for that year are $301 million. What does that mean? If Massey had no debt, it would have made a profit! That is, if Massey had been an all-equity-financed firm, it would have made a profit. Massey's interest costs were greater than its income. Massey was not losing money on operations, Massey was losing money on its financing!

Bottom Line: How You Finance Yourself Matters!

If Massey had been an all-equity firm it would have shown a profit in 1980. But Massey was not an all-equity firm. Massey had debt, and its annual interest costs were $301 million. As a result, it ended up with a loss of $225 million. Now what happens next? What does the loss mean to Massey? First, Massey has to finance the loss. It means it has to come up with $225 million, and it has to do it now.

Where is Massey going to get this cash? Massey can sell equity. But what has happened to its stock price? It tanked, as can be seen in Figure 5.3.

Figure 5.3A Massey Ferguson Stock Prices, 1971–1982

Figure 5.3B Massey Ferguson' Market Capitalization, 1971–1982

By December 1980, the value of Massey's equity (or market cap) fell to $68.4 million. To raise $225 million means Massey would have to sell an amount of equity equal to three times the current total equity value of the firm. Firms typically sell only about 10% of the value of their existing equity at a time. Selling 300% of your equity is probably impossible.

So what else can Massey do? It has already sold assets, laid off workers, and cut inventory. Issuing enough equity is not feasible. This means its only alternative is to issue more debt. Should it be long- or short-term debt? Massey decided to issue short-term debt. Why? As equity prices fell and Massey's financial troubles became apparent, no one wanted to lend to Massey long term, so the firm had no choice.

Why were Massey's options so limited? Partly because its problems happened so rapidly. Massey had to cover its spiraling losses and had no financial flexibility when bad times hit. Financial flexibility is an important, although abstract, concept that firms should consider when choosing a capital structure.

These results can be seen in Table 5.2. In 1976 Massey's debt level is 46.9%, in 1977 it is 54.4%, in 1978 it is 67.6%, in 1979 it is 67.4%, and in 1980 it is 82.3%. Furthermore, the increases are funded with short-term debt.

TABLE 5.2 Massey's Debt 1976–1980

| ($ millions) | 1976 | 1977 | 1978 | 1979 | 1980 |

| Short-term debt | 180 | 345 | 477 | 571 | 1,075 |

| Long-term debt | 529 | 616 | 652 | 625 | 562 |

| Total debt | 709 | 961 | 1,129 | 1,196 | 1,637 |

| Owner's equity | 803 | 807 | 541 | 578 | 353 |

| Debt/(debt + equity) | 46.9% | 54.4% | 67.6% | 67.4% | 82.3% |

In 1980, Massey's short- and long-term debt combined is $1.6 billion. This happened because Massey had losses of $262 million in 1978 and $225 million in 1980 (Massey had a small profit of $37 million in 1979), which it had to cover by borrowing. Every time Massey borrowed its debt rose, which meant its interest costs kept going up, making its losses larger. This is a downward spiral that is picking up speed.

To recap, Massey has a high debt level while operating in a risky product market business. Adversity hits, and it starts generating losses. With no other options, Massey funds the losses with short-term debt. This leads to higher leverage and even larger losses. Massey, in turn, funds these losses with more debt and continues to cycle downward. Importantly, during this time, Massey is breaking even, or even making a profit, on the operating side. But on the financial side Massey is losing money because of the firm's debt financing, and the losses are getting worse and worse. And what happens to Massey's stock price? Massey's stock price between 1976 and 1980 loses 87% of its value. On June 30, 1976, the market value of Massey's equity (market cap) was $524.7 million. By December 1980, Massey's market cap had fallen to $68.4 million. Massey now has debt of $1.6 billion (and total liabilities of $2.5 billion) and equity with a market value of $68 million. Thus, even if Massey was able to issue equity, Massey could never issue enough equity to pay off its debt since the debt is 24 times its equity.

CONRAD RUNS AWAY

In October 1980, when Massey's equity was still worth $100.4 million, Conrad Black made the decision to give away his equity stake in Massey. Not sell it, give it away. To whom? The worthiest charity he could find—Massey's union, that is, the employees. Why did he do this? Partly because of a tax break, partly because he knew Massey was in severe trouble, partly because he was tired of people coming to him and asking him (the largest equity holder at the time) what he was going to do about Massey. When a firm is in trouble, the banks that lend to it are in trouble. Therefore, these banks are knocking on Conrad Black's door, asking him when he will put more equity in. And his response? I'm not. His response is to wash his hands of the firm.9

In reality, Conrad Black did not give the equity to the workers so that they could bail out Massey. The purpose of Conrad Black donating his equity stake to the union was to put the onus on the Government of Canada to bail Massey out. He figuratively walks up to the government's doorstep, puts Massey on the doormat, rings the doorbell, and runs. Pierre Trudeau, then prime minister of Canada, opens the door and sees Massey Ferguson lying there on his doorstep.

THE COMPETITORS

We should not just pick on Massey. How did Massey's direct competitors, International Harvester and John Deere, do during this time period? (See Table 5.3.)

TABLE 5.3 A Competitive Comparison

| Firm | Massey | Massey | Harvester | Harvester | Deere | Deere |

| Year | 1976 | 1980 | 1976 | 1980 | 1976 | 1980 |

| Profit margin | 4.3% | –7.2% | 3.2% | –6.3% | 7.7% | 4.2% |

| Debt/debt + equity | 46.9% | 82.2% | 43.9% | 53.6% | 31.3% | 40.6% |

| % of three firms' sales | 24.3% | 21.0% | 48.2% | 42.4% | 27.5% | 36.7% |

| Interest coverage | 2.8 | 0.3 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 4.4 | 2.8 |

Harvester was technically in default at the end of 1980. It was doing okay until 1979, and then it basically fell off its tractor. In 1979, Harvester had a net worth of $2.2 billion, but by 1982 its net worth was only $23 million. Thus, it lost almost $2.2 billion in a three-year period. How did it do that? Harvester's downfall was at least partly due to a labor dispute triggered by Harvester's recently hired CEO, Archie R. McCardell. Harvester hired McCardell from Xerox, which was not a unionized firm. Mr. McCardell came in having never dealt with unions before, while Harvester's labor force was organized by the United Automobile Workers union (UAW), known for its labor disputes and strikes.

McCardell's goal was to make Harvester the industry's low-cost producer and believed the principal way to achieve this was by lowering labor costs. So when the existing union contracts expired, McCardell pushed for concessions from the UAW. This precipitated a 172-day strike, the fourth-longest in UAW history until that point. By the time the strike ended, the union had conceded very little, but International Harvester had lost $479.4 million and then lost another $397.3 million in the next fiscal year.10

Meanwhile, how did Deere do? From 1976 to 1980, John Deere's sales increased by 74.5%, or about 15% per year. In 1976, John Deere had 27.5% of the three-firm (Massey, Harvester, and Deere) market share. By 1980, while Deere's profit margins had declined slightly (gross profit fell from 26.1% to 20.5% and net profit fell from 7.7% to 4.2%), it had 36.7% of the three-firm market share.11

So how did John Deere do it? Did it have a better product? Did it not experience the downturn? Deere didn't have Massey's problems with political risk in other countries, but North America was still impacted by the recession. However, while the economy turned down overall, Deere's share of the total market went up, from 19.1% to 23.3%. Not only did it increase its market share, but Deere also started spending heavily on major investments in plant and equipment (capital expenditures or CAPEX). To understand why, consider the demand for farm equipment. It is a cyclical business. And what part of the cycle was the industry at during 1976–1980? The bottom. What are firms supposed to do at the bottom of a cycle? Invest for the coming upturn.

Deere had come to the same conclusion as Harvester: production costs were too high, and it needed to become a lower-cost producer. However, Deere used a different approach to achieve this objective. Instead of seeking wage concessions from the union, it decided to use less labor. Deere built the largest automated tractor plant in the world to lower its costs of production. In a seven-year capital program ending in 1981, it spent $1.8 billion,12 a huge amount, on CAPEX at the time. In addition, it started to recruit its competitors' best dealers.

Farm equipment dealers, just like auto dealers, are often independent businesses. If you recall, Massey lost a large number of its dealers during the downturn. Were all the dealers that Massey lost bad dealers? Some were among its least profitable dealers, but many were among its most profitable. Deere targeted Massey Ferguson's best dealers and picked off many of them during Massey's troubles.

Thus, Deere is successfully recruiting new dealers, increasing market share, and spending a large amount on capital expenditures. It is positioned to be the low-cost producer in North America. How is Deere able to do this? Deere can do this because it started with a low debt level. In 1976 it was financed by only 31.3% debt, which rose to 40.6% in 1980. Even at 40.6%, Deere had a lower percentage of debt than the 46.9% Massey started with in 1976. The low debt level provided Deere with something Massey did not have: financial flexibility. Deere's lower debt ratio kept it from being paralyzed by financial constraints; it gave it the opportunity to expand, even in adversity. Massey and Harvester were both vulnerable, and Deere used its financial flexibility as a competitive advantage.

As an aside, you don't necessarily have to wait for adversity; sometimes you can create it. For example, IBM at one time was the premier firm in its industry, and other firms competed for niches of IBM's markets. One example was Telex, which was growing rapidly in some of IBM's markets. Suddenly, IBM lowered prices on a number of products that competed with Telex. Telex's revenues fell, and its profits turned to losses, causing Telex to violate its loan covenants, pushing Telex into bankruptcy. It was discovered in subsequent court testimony that IBM had reviewed Telex's financial filings and built a pro forma (forecast) model to figure out by how much IBM needed to lower prices to cause Telex to violate its covenants. IBM claimed that it was not its corporate policy to do this, that it was a rogue IBM analyst who did the analysis, and that this was unknown to senior management. Regardless, the moral here is that if you are the firm that is best able to survive the next financial crisis and a crisis does not present itself, sometimes it is possible/advantageous to create one.13

Returning to our discussion of Deere versus Massey: the risk of debt financing is not simply whether a firm can make debt repayments during bad times. The risk of debt financing is that it also leaves a firm vulnerable to a competitive attack.

With Deere now solidly number one, does this mean that Massey is safe? No. Why not? What can Deere do to Massey now? It could go after Massey internationally, but that would mean Deere would have to change its product line, so Deere will probably not take that route. What else can Deere do? Suppose you are John Deere himself. You are sitting on your porch in Moline, Illinois (Deere's Corporate Headquarters). What do you do now?

On January 2, 1981, Deere announces a 4-million-share issuance of common stock at $43 per share (or $172 million in new equity). Deere knows the farm equipment market is down and Deere's stock price is also down, but it is still going to issue new equity. The stock market is not amused at this news, and Deere's stock market capitalization (the value of the current outstanding equity) falls $241 million, on a market-adjusted basis, the day of the announcement.14 That is, Deere announces it is going to raise $172 million in new equity, and the value of the current outstanding equity falls $241 million. We'll discuss why this occurs in a few chapters. The point here is that Deere decided it was worth losing $241 million of market value in order to obtain $172 million in cash (from the new equity issue) so it can decrease its debt ratio from 40% back to the mid-30s.

If you are Massey Ferguson, what is the first thought in your mind? Oh, Massey is essentially lying on the floor, writhing in pain with massive debt. Deere has been eating Massey's lunch—taking its dealers, capturing market shares—and now, all of a sudden, Deere issues new equity and brings its debt level back down to 30%. This is known in financial strategy terms as “reloading.” You're in trouble, and your major competitor, Deere, is willing to issue equity even when stock prices are low in order to finish you off.

BACK TO MASSEY

So let's go back to Massey. How do you fix this company? In 1980, Massey is in default. It has $1.637 billion in debt, $1.075 billion of it short term. This means Massey has to frequently refinance. The book value of its equity is $353.1 million. Its debt-to-equity ratio is 464% (1.637/0.353). What are Massey's options? Sell off its crown jewel, the diesel engine manufacturing facility, Perkins? Sell off everything but Perkins? Do a financial restructuring, including perhaps an exchange offer? Seek a government bailout? File for bankruptcy? Anything else?

One thing a firm in trouble can do is find a merger partner. In December 1980, the market cap of Massey is $68 million. This means a firm can buy Massey Ferguson, one of the first true multinationals, a firm known throughout the world, for $68 million. Is that a lot of money? Not really. The investment banker fees on the 1985 RJR Nabisco merger were over $500 million15 (in other words, that's just what the investment bankers made). And you can buy all of Massey Ferguson for $68 million.

So why doesn't someone buy Massey? Simply put, it has too much debt. The problem is if you acquire Massey before it files for bankruptcy, you also acquire its debt. This is why distressed firms rarely merge until after bankruptcy, when the debt is wiped out. Currently, you can buy Massey's equity for $68 million, but it comes with $1.6 billion of debt. Furthermore, after buying Massey, you would have to invest additional funds for capital expenditures to get your operating costs down. And then what would you have? John Deere is still there reloading. It is like buying a house that is a fix-me-up special. If you buy it before foreclosure, you have to assume the present mortgage. Even if you buy it after foreclosure, you have to put money into it. Finally, there is a huge Doberman Pinscher next door (named John Deere) that chews on your leg every time you step outside the house. Nobody is going to merge with you, at least not until after bankruptcy.

So what about selling off Perkins, the crown jewel? Well, this sounds like a good idea, but Massey's debt holders (the people who lent Massey money) aren't stupid (although they did lend Massey money). When Massey borrowed funds, the lenders inserted covenants into the loan contracts. And guess what those covenants say? Basically, Massey can't sell the assets without permission from the lenders, who are never going to let Massey sell Perkins unless they get completely paid off from any proceeds first. So selling Perkins, Massey's crown jewel, is really not a viable option.

What about selling off everything else? Massey's main asset, other than Perkins, is its receivables. Normally, when we think about liquidation values for receivables, we would use some fraction of face value (e.g., 50% or 75%). However, what are Massey's receivables worth? What are the farmers' receivables worth? What are the Shah's receivables worth now that the Ayatollah is in control? Massey sold lots of equipment to the Shah, to less developed countries, to Brazil, and so on. What is this all worth? Not 75%, not 50%. Receivables are only worth what a firm expects to collect on them. Massey's receivables are potentially worth next to nothing because they will be difficult if not impossible to collect.

Perhaps Massey should try to renegotiate with its lenders, the banks. It is typical of a firm in financial trouble to offer the debt holders partial payment through an exchange offer or renegotiation. Unfortunately, this is also problematic for Massey. Normally the CEO and CFO would jump into a cab and say, “Take us to the head office of our bank.” In Massey's case, the cab driver asks, “Which bank?” Massey has borrowed money from 250 banks in 31 countries, each one of which can individually take Massey into bankruptcy if it is not repaid or restructured. This is not how multibank lending is usually structured. Usually a firm has an agent bank (also known as a lead bank) that is in charge of a consortium or syndicate of banks. A firm borrows money from the whole consortium, and the lead bank is the one who negotiates the terms of the deal. So normally, all a firm needs to do is head over to its lead bank to negotiate.

Massey did not use a single lead bank. It has separate agreements with 250 banks.16 So for Massey to renegotiate its debt, it must deal separately with each bank. Why did Massey borrow this way? It was cheaper at the time for Massey. It obtained the lowest cost of money, loan by loan, bank by bank, by borrowing money all over the world. However, this makes it extremely hard to renegotiate in times of financial distress.

Deere, on the other hand, borrowed from a few banks, all of which are part of a long-term consortium. Deere pays more to do it this way, but it is a lot easier to renegotiate.

Thus, Massey faces a nightmare now that it has to refinance. All of its potential sources of funding have problems. If they go to its current bankers and ask for more money, the banks will likely tell them, “We are done.” If Massey goes to its largest stockholder, Conrad Black, he says “I'm out.” If Massey goes to the union, the UAW, and asks for concessions, the union's reply is likely to be, “Didn't you watch what just happened with International Harvester?”

This leaves management with what options? A government bailout? Which governments? Canada and the UK? The U.S. government is not going to give Massey anything because it has no stake. Canada had a stake because Massey's operations employed a significant number of workers. The UK had an even larger stake due to the Perkins subsidiary there. So who is Massey going to ask? Will it ask Margaret Thatcher of the UK or Pierre Trudeau of Canada?

What is Maggie going to say, setting aside her political beliefs about government ownership?17 She will say no because the jobs in the UK are at Perkins, which is probably the part of Massey that will survive the bankruptcy intact. There is no threat to the UK because those jobs aren't going to go away.

Canada is where the at-risk jobs are located, and Pierre Trudeau's political philosophy is more labor-oriented than Margaret Thatcher's. So Massey goes to Canada, and Canada says what? We can't just give you the money, and we can't lend you the money, but we'll guarantee a new loan. What does that mean? If Massey borrows from a bank, the Canadian government will guarantee the repayment. If Massey does not pay, then Canada will. Why doesn't the Canadian government just lend the money themselves? Well, politically it is always easier for governments to guarantee money because it does not look like they are actually giving anything of great value (and if anyone had a worse Balance Sheet than Massey, it was the Canadian government at the time). It's an off-Balance-Sheet guarantee.

MASSEY'S RESTRUCTURING

In 1981, representatives of Massey's 250 bankers met in London at the Dorchester hotel. They took up half the hotel's rooms. They agreed to put in $360 million in new financing and convert Massey's $1 billion in short-term debt to long-term debt. Of the $360 million in new money, $160 million was new long-term debt, and $200 million was preferred stock (redeemable after 10 years, paying a 10% dividend and guaranteed by the government of Canada). The terms of the guarantee stated that the government of Canada would pay if Massey could not. In addition, it was agreed that Massey would pay no dividends on its common stock for 10 years.

What did the banks get for agreeing to the restructuring and for investing $360 million in new funds? The banks received debt and 36 million new shares of common stock plus warrants to buy another 40 million new shares of common stock at $5 a share (or a total potential 76 million new shares). Furthermore, $200 million of new funds is guaranteed by the Canadian government. Finally, the banks did not forgive any debt, although the short-term debt was exchanged for long-term debt.

Prior to the restructuring, there were 18 million shares of common stock outstanding. This means Massey's common stock increases from 18 million current shares to 94 million potential shares. Although technically not a bankruptcy, the old shareholders are washed away in a sea of paper. Before, they owned 18 million shares out of 18 million, and now they own 18 million shares out of a potential 94 million shares (with all the new shares going to the bankers).

In essence the restructuring caused the accounting reality to match the economic reality. Did Massey's lenders really have short-term debt before? No, there really was no short-term debt because there was no way Massey could repay anything in the short term. The restructuring converted the short-term debt to long-term debt. Moreover, the old accounting reality did not recognize that the banks were already in effect equity holders in Massey. If Massey can't pay off the $1.6 billion in debt in the long term, the banks become the firm's principle equity holders. The issuance of 36 million shares of new equity automatically gave the banks 67% ownership with a potential for an even greater percentage if the warrants are exercised. Massey's Balance Sheet liabilities were an accounting fiction prior to the restructuring, and the restructuring adjusted the Balance Sheet to more accurately reflect economic reality.

Now, as simple as the agreement was conceptually, the negotiation process was extremely complex. Massey faced 250 bankers, and every one of them had the ability to hold out and threaten the deal unless they got a bigger share. Each one was saying, “If you want this deal, you need me to agree, and I want to be repaid 100%.” Massey escaped bankruptcy, and the lenders agreed in large part because (a) the banks forgave interest and exchanged some debt into equity, and (b) the Government of Canada guaranteed U.S. $102 million and the Government of Ontario guaranteed U.S. $62 million of new preferred shares.18

To complete the restructuring, the old shareholders had to agree by a vote. However, the old shareholders didn't really have any choice. If Massey files for bankruptcy, what do the old shareholders get? Zero, or close to it. If the deal works, what do the shareholders get? At least as much, if not more. For example, if the company turns around with this deal and the shares go back to $5 and the warrants kick in, the shareholders will have 18 million out of 94 million shares. This is approximately 20% of the 94 million shares, and if the shares are worth $5 or more, this represents at least $90 million to the old shareholders. From the old shareholders' point of view, it is worth rolling the dice. So the banks and shareholders agree to the restructuring, and everyone pours out of the Dorchester hotel, down Park Lane, and heads off to Heathrow airport.

Massey's first restructuring deal concluded in July 1981. In May 1982 the firm stopped paying dividends on the Canadian government guaranteed preferred stock. As a result, the Canadian government stepped in and repurchased Cdn. $200 million of preferred stock. Then a second restructuring deal, completed in March 1983, included further interest waivers, conversions of debt into equity, and additional new equity.

Our next question is: Will this industry ever come back? Yes. Why? Farmers will eventually buy tractors for two reasons. One, people have to eat, and, two, tractors wear out. Since sales are currently below replacement levels, the industry will come back.

When the industry does come back, who is going to be one of the clear winners? Deere. Why? Deere expanded its dealer network, expanded its market share, built new plants, and is now the low-cost producer, so it should come back as number one.

Key Point #1: Matching Business Strategy to Financing Policy

Let us now return to the 1971–1976 time period and ask: With hindsight, what should Massey have done differently? First, change its leverage. What should Massey's debt level have been? 30%. Why? Primarily because Deere was at 30%. It is dangerous for a firm in an industry to have a much higher debt level than its major competitors. How could Massey get to 30%? It would have had to issue equity if it was going to continue to grow as quickly. What about Conrad Black getting diluted? He got diluted down to zero anyway because he gave his shares away, and even if he kept them, the restructuring would have diluted him—a smaller percentage of something is worth more than a higher percentage of nothing. Bottom line: Massey should have issued equity or grown more slowly. But growing more slowly would not have made a lot of sense if Massey was really trying to implement a developing-world strategy.

How about the maturity of Massey's debt? Should it have been long or short? Long. Massey wants to avoid refinancing in an economic downturn. This means Massey should only have long-term debt so that if there is a downturn, it doesn't have to worry about refinancing when it is in trouble.

What about the interest rates? Should they have been fixed or floating? Fixed. If interest rates go up, Massey's sales drop because farm equipment demand is sensitive to interest rates. Massey needs to avoid rising interest costs during periods when its sales are declining.

Now if Massey wants long-term, fixed-rate debt, it means no more bank debt. Bank debt is almost always short-term, floating rate debt. Bank debt can be intermediate term, but the maturity will be on the short end of the spectrum.19 Where will Massey borrow from if it no longer borrows from the banks? The public capital markets. Massey should finance with long-term, fixed-rate debt. Its capital structure should be approximately 30% debt (70% equity).

Finally, what should Massey's dividend policy be? Low. We'll discuss dividends later in the book. However, Massey should have minimal dividends, and it should use its earnings for growth instead.

More generally: Optimal capital structure depends on a firm's product market strategy. You need to understand the industry and the firm's product market before deciding on its financing.

Key Point #2: It Can Be Too Late to Unlever

Once financial distress hits, it may be too late for a firm to unlever. Firms with high debt ratios (and high interest costs) can spiral down quickly. High leverage can also preclude a firm from issuing new long-term debt financing (short of restructuring), or equity due to the debt-overhang.20 The firm may be able to issue short-term debt, but doing so potentially makes the situation riskier, and the short-term debt would need to be constantly refunded. This is why firms need to continually monitor their leverage and issue equity well before any hint of financial distress.

Key Point #3: The Costs of Financial Distress

What are the costs of financial distress? While they include all the legal fees, the hotel fees at the Dorchester, and so on, these are not the primary costs.

What are the primary costs of financial distress? The firm's long-run competitive prospects. Massey was permanently damaged. First, John Deere came in and took market share away from Massey. This competitive loss is a real cost. Second, Massey had to pull back its developing-world expansion program. This allowed the Korean and Japanese small-tractor manufacturers to enter the market and take that market away from Massey permanently. So Massey lost not only its U.S. market share to John Deere, but also developing-world market shares to foreign competitors. Thus, the true costs of financial distress are not simply the cost of the legal bills. It's all the rest. Debt has advantages: it has a lower cost than equity and provides a higher ROE than equity. However, it also comes with a high cost during financial distress.

Can financing policy become a strategic weapon? Yes. We have seen that a firm's financing policy affects its cost of capital. We have also seen that financing policy affects a firm's ability to respond in periods of market turmoil or downturn. If a firm follows a financial policy riskier than that of its competitors, not only is the cost of capital higher, it potentially puts its product market operations at risk during economic downturns.

If a firm has more financial slack than its competitors, not only can this financial slack help the firm survive periods of product market downturns, it may also be utilized as a weapon against its competitors. That is, a well-financed firm can, in times of distress, increase investments, cut costs, cannibalize dealers, and increase market share.

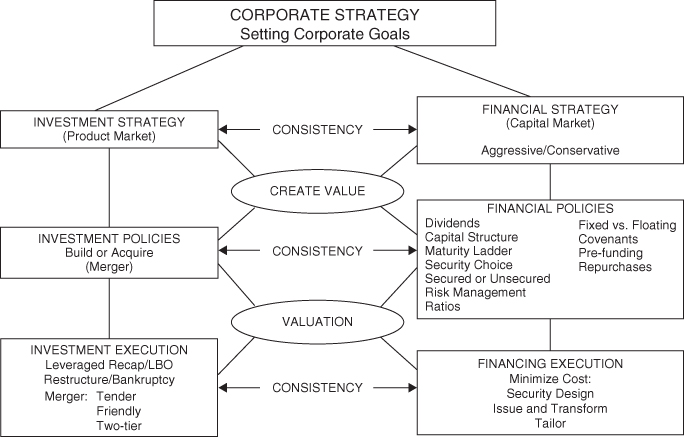

Examining Key Point # 1 (Financing Strategy and Product Market Strategy Must Be Aligned) Schematically

We really can't emphasize enough that corporate finance should always start with a firm's product market strategy. It is really hard to set a firm's financial strategy unless you know the firm's product market strategy. What are the firm's key risks, what are its competitors doing, what funds are required for upcoming projects/investments, and so on? Only after knowing these things can a firm set a financial strategy, which can either be (1) conservative and supportive, even at some cost, or (2) aggressive and revenue maximizing.

To better organize your thoughts, return to the schematic overview of how your authors think about corporate finance (first shown in Chapter 1).

In Figure 5.4, we place the firm's product market strategy at the top. The firm's financial strategy is set in the tier below product market strategy and is characterized as being either conservative and enabling, or aggressive and money making. Massey's decisions on debt financing can be characterized as aggressive (borrowing at the cheapest rate anywhere in the world is aggressive and money making). This decision is fine as long as it does not compromise the firm's product market strategy. In addition, not having an agent bank may be cheaper, but it can become a problem later.

FIGURE 5.4 Schematic of Corporate Finance

Once the financial strategy is set, the firm then determines its financial policies (the third tier on our diagram). The diagram outlines some of the important financial policies on which a firm must decide. Choices like the amount of leverage, fixed versus floating interest rates, long- versus short-term debt maturities, dividend policy, which markets the firm issues in (e.g., the U.S. or the euro market), liquidity management, whether to issue common equity or preferred shares, whether to issue convertible debt or straight debt, and so on.

In this chapter, we have discussed the first two tiers of this diagram: Which financing strategy should a firm choose? Over the remaining seven chapters of this unit, we will continue to go down this paradigm and review all of the tiers, in particular, the specific policies in tier 3. We will also discuss how these policies are best implemented to maximize firm value.

As a preview, corporate financing policies are not limited to just deciding on the percentage of debt versus the percentage of equity. They also involve deciding if the debt should be long term or short term, whether the coupon rate is fixed or floating, and whether the debt is issued in the United States or elsewhere. Corporate financial policies are also about whether dividends should be paid or not, and if paid, at what level. They are about whether equity issues should be for common stock or for preferred stock, and whether common stock should be issued or done “back door” as convertibles. And so on, as we shall see in the upcoming chapters.

POSTSCRIPT: WHAT HAPPENED TO MASSEY

So what happened to Massey? The firm did not do very well. It went back to the Canadian government and asked for more money. What did Canada say? Canada said no this time. However, unfortunately for Canada, the government lawyers who had drawn up the indenture for the preferred stock were not securities lawyers trained in how to write proper covenants. The Canadian government lawyers had failed to insert a provision forcing Massey to pay the preferred stockholders a dividend if the firm had the money. So Massey told the Canadian government that if the government refused to give the firm more money, then Massey would not pay the preferred dividend. When Massey skipped the preferred dividend, this caused the preferred stock to default and forced the Canadian government to come up with the $200 million cash guarantee.

Victor A. Reich, who took over Massey as CEO (in 1981), made a stunning confession in a press conference in 1985 when he said, “1984 was a disappointing year. Why should 1985 be any better?” You know a firm is in trouble when the CEO says that. By the end of 1986, Massey had sold all their farm equipment businesses and changed their name to Varity.21

What happened to Harvester? It went bankrupt as well and changed its name to Navistar. One thing a firm usually does when it goes bankrupt is change its name and pretend it is not the same firm anymore—we assume it believes that customers and investors won't remember who it is.

Korean and Japanese manufacturers took away the developing world-world market from Massey. John Deere became the largest North American tractor manufacturer, capturing most of Massey and Harvester's market shares.

SUMMARY

- Examining the product market strategy, we see that Massey is a firm in a risky industry with a riskier product market strategy than its competitors. In addition, Massey follows a riskier financial strategy than its competitors. Thus, Massey is riskier in the product market and in its financial strategy.

- When adversity hit, Massey's losses were not due to its operations. The losses were due to its high interest costs. Remember that as an all-equity firm Massey would have actually made money from its operations. Massey funded its initial losses with more debt, starting a downward spiral. Massey then became paralyzed by the costs of financial distress. All this happened very quickly. Once Massey started losing $300 million a year, it had to finance that $300 million a year, each and every year.

- The principal costs of financial distress aren't the legal and hotel bills. Rather, the principal costs of financial distress are the permanent loss of competitive position in the product market. Massey lost its developing-world market to foreign competitors and its U.S. market to John Deere.

- The trade-off between the benefit of debt and the cost of financial distress is driven by basic business risk (BBR). We will talk a lot more about BBR in the coming chapters. Remember, there are two kinds of risk for the firm: basic business risk (which depends on the firm's business strategy) and financial risk (which depends on a firm's financial strategy). Whether these two risks are dependent or independent of each other is why it is necessary to know the firm's product market strategy before we can set the firm's financial strategy.

A caveat: A risky product market strategy does not necessarily mean a firm should choose a safe financial strategy and vice versa. The reason Massey should have chosen a safe financial strategy, given its risky product market strategy, is because of the firm's competitive situation. Sometimes a firm actually wants to have risky product market and risky financial strategies. Sometimes a firm wants to have safe product market and safe financial strategies. Too many students take away the lesson from Massey that if the firm is risky on one side it should be safe on the other. This is not correct.

Let us provide an example. Consider a firm drilling for oil (i.e., punching holes in the ground). It is a 0, 1 risk (the firm will find oil or it won't). Competitively, what the firm's competitors do does not affect whether the firm finds oil or not for any particular well. Drilling for oil is a very risky product market strategy. How should it be financed? It should be financed as risky as possible (with possible 100% debt). Why? The firm wants to be financed with other people's money. The firm wants to borrow, so that if the firm does not find oil, the lender takes the loss. However, if the firm does find oil, it pays off its lenders a fixed amount, and its shareholders get all upside. It's like going to Vegas to play the roulette table and financing yourself with borrowed money. If you finance your gambling with equity shares, then you have to share any winnings. However, if you borrowed your gambling stake, you pay the lenders their principal plus interest and get to keep virtually all the winnings. Essentially you are risking other people's money while retaining all the upside. So in these situations with a risky product market, the proper financial strategy is a risky one. Massey, however, had a risky product market strategy and required a safe financial strategy because of their competitive situation.

- Finally, we apply the concept of sustainable growth again. (It was previously mentioned in Chapter 2 with PIPES.) How fast a firm can grow without going for outside financing depends on the firm's sustainable growth rate. Almost every firm at some time in their history has to go for outside financing.

So, bottom line, how a firm is financed matters. It is not enough simply to obtain the lowest-cost financing.

Coming Attractions

Our next chapter will provide the underpinnings of the theory of capital structure.

APPENDIX 5A: MASSEY FERGUSON FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

Balance Sheets

| ($000s) | 1971 | 1972 | 1973 | 1974 | 1975 | 1976 |

| Cash | 33,060 | 9,859 | 8,096 | 13,324 | 20,107 | 6,960 |

| Receivables, net | 339,102 | 368,480 | 416,669 | 432,894 | 488,801 | 557,777 |

| Inventories | 335,419 | 362,236 | 461,584 | 711,253 | 866,326 | 966,823 |

| Other | 30,023 | 33,388 | 52,232 | 65,060 | 71,303 | 83,655 |

| Current assets | 737,604 | 773,963 | 938,581 | 1,222,531 | 1,446,537 | 1,615,215 |

| PP&E net | 186,270 | 180,442 | 205,540 | 278,270 | 400,915 | 519,984 |

| Other long term | 87,154 | 102,910 | 104,923 | 113,150 | 134,574 | 169,946 |

| Total assets | 1,011,028 | 1,057,315 | 1,249,044 | 1,613,951 | 1,982,026 | 2,305,145 |

| Bank loans | 167,687 | 139,736 | 80,591 | 162,824 | 170,246 | 113,430 |

| Current debt | 8,348 | 9,844 | 13,161 | 16,456 | 47,296 | 66,447 |

| Accounts payable | 200,199 | 212,416 | 332,150 | 466,892 | 532,963 | 632,975 |

| Other | 26,192 | 39,117 | 73,975 | 74,995 | 79,660 | 70,541 |

| Current liabilities | 402,426 | 401,113 | 499,877 | 721,167 | 830,165 | 883,393 |

| Long-term debt | 186,963 | 195,787 | 243,858 | 325,732 | 452,338 | 529,361 |

| Other | 17,903 | 16,382 | 35,364 | 43,430 | 58,031 | 89,370 |

| Total liabilities | 607,292 | 613,282 | 779,099 | 1,090,329 | 1,340,534 | 1,502,124 |

| Contributed capital | 176,061 | 176,061 | 176,719 | 176,865 | 216,084 | 277,024 |

| Retained earnings | 227,675 | 267,972 | 293,226 | 346,757 | 425,408 | 525,997 |

| Owners' equity | 403,736 | 444,033 | 469,945 | 523,622 | 641,492 | 803,021 |

| Total liability and equity | 1,011,028 | 1,057,315 | 1,249,044 | 1,613,951 | 1,982,026 | 2,305,145 |

| ($000s) | 1977 | 1978 | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 |

| Cash | 12,575 | 23,438 | 17,159 | 56,200 | 65,200 | 108,100 |

| Receivables, net | 542,422 | 556,718 | 731,100 | 968,200 | 952,400 | 671,000 |

| Inventories | 1,135,950 | 1,083,822 | 1,097,598 | 988,900 | 747,100 | 625,900 |

| Other | 80,797 | 63,830 | 89,853 | 93,000 | 73,500 | 63,700 |

| Current assets | 1,771,744 | 1,727,808 | 1,935,710 | 2,106,300 | 1,838,200 | 1,468,700 |

| PP&E net | 594,084 | 602,242 | 568,653 | 488,200 | 407,800 | 335,100 |

| Other long term | 227,984 | 243,305 | 241,081 | 236,100 | 257,400 | 265,400 |

| Total assets | 2,593,812 | 2,573,355 | 2,745,444 | 2,830,600 | 2,503,400 | 2,069,200 |

| Bank loans | 249,238 | 362,270 | 511,723 | 1,015,100 | 123,500 | 131,600 |

| Current debt | 95,821 | 115,009 | 59,298 | 60,200 | 42,100 | 21,800 |

| Accounts payable | 677,021 | 751,383 | 907,365 | 793,800 | 364,800 | 284,900 |

| Other | 53,015 | 68,081 | 31,120 | 24,500 | 313,400 | 307,500 |

| Current liabilities | 1,075,095 | 1,296,743 | 1,509,506 | 1,893,600 | 843,800 | 745,800 |

| Long-term debt | 616,390 | 651,800 | 624,841 | 562,100 | 1,031,300 | 1,024,600 |

| Other | 96,086 | 82,796 | 32,877 | 18,800 | 58,600 | 62,200 |

| Total liabilities | 1,787,571 | 2,031,339 | 2,167,224 | 2,474,500 | 1,933,700 | 1,832,600 |

| Contributed capital | 277,024 | 272,678 | 272,678 | 272,700 | 685,400 | 765,500 |

| Retained earnings | 529,577 | 268,644 | 305,542 | 80,400 | −115,700 | −528,900 |

| Owners' equity | 806,601 | 541,322 | 578,220 | 353,100 | 569,700 | 236,600 |

| Total liability and equity | 2,594,172 | 2,572,661 | 2,745,444 | 2,827,600 | 2,503,400 | 2,069,200 |

Income Statements

| ($000s) | 1971 | 1972 | 1973 | 1974 | 1975 | 1976 |

| Net sales | 1,029,338 | 1,189,972 | 1,506,234 | 1,784,625 | 2,513,302 | 2,771,696 |

| COGS | 814,648 | 932,517 | 1,167,145 | 1,383,048 | 1,945,484 | 2,117,514 |

| Gross profit | 214,690 | 257,455 | 339,089 | 401,577 | 567,818 | 654,182 |

| SG&A | 167,583 | 186,982 | 219,798 | 245,067 | 324,291 | 369,309 |

| Operating profit | 47,107 | 70,473 | 119,291 | 156,510 | 243,527 | 284,873 |

| Interest expense | 50,549 | 43,306 | 48,065 | 77,880 | 133,779 | 100,586 |

| Other | 13,178 | 15,287 | 16,939 | 19,792 | 23,794 | (14,910) |

| Profit before tax | 9,736 | 42,454 | 88,165 | 98,422 | 133,542 | 169,377 |

| Income tax | 5,675 | 15,787 | 35,804 | 36,505 | 47,874 | 61,168 |

| Other net of tax | 5,194 | 13,630 | 5,852 | 6,496 | 9,009 | 9,705 |

| Net profit | 9,255 | 40,297 | 58,213 | 68,413 | 94,677 | 117,914 |

| ($000s) | 1977 | 1978 | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 |

| Net sales | 2,805,262 | 2,630,978 | 2,972,966 | 3,132,100 | 2,646,300 | 2,058,100 |

| COGS | 2,209,708 | 2,118,994 | 2,400,408 | 2,576,200 | 2,333,400 | 1,808,000 |

| Gross profit | 595,554 | 511,984 | 572,558 | 555,900 | 312,900 | 250,100 |

| SG&A | 399,875 | 390,668 | 410,125 | 464,400 | 470,000 | 393,600 |

| Operating profit | 195,679 | 121,316 | 162,433 | 91,500 | (157,100) | (143,500) |

| Interest expense | 150,981 | 154,744 | 164,166 | 300,900 | 265,200 | 186,700 |

| Other | (14,128) | (63,445) | 33,814 | 6 | 18,300 | 13,500 |

| Profit before Income tax | 30,570 | (96,873) | 32,081 | (209,394) | (404,000) | (316,700) |

| Income tax | 11,387 | (17,458) | (6,250) | (10,100) | (8,800) | (3,300) |

| Other net of tax | 13,537 | (182,980) | (1,433) | (25,906) | 200,400 | (99,800) |

| Net profit | 32,720 | (262,395) | 36,898 | (225,200) | (194,800) | (413,200) |

Ratios

| 1971 | 1972 | 1973 | 1974 | 1975 | 1976 | |

| Profitability | ||||||

| Sales growth | 9.75% | 15.61% | 26.58% | 18.48% | 40.83% | 10.28% |

| ROA (NI/TAbeginning-year*) | 0.91% | 3.99% | 5.51% | 5.48% | 5.87% | 5.90% |

| ROE (NI/OEbeginning-year*) | 2.35% | 9.98% | 13.11% | 14.56% | 18.08% | 18.38% |

| Profit margin | 0.90% | 3.39% | 3.86% | 3.83% | 3.77% | 4.25% |

| Activity: | ||||||

| Accounts receivable/sales | 32.94% | 30.97% | 27.66% | 24.26% | 19.29% | 20.12% |

| Inventory/sales | 32.59% | 30.44% | 30.64% | 39.85% | 34.96% | 34.88% |

| Net PP&E/sales | 18.10% | 15.16% | 13.65% | 15.59% | 15.95% | 18.76% |

| Total assets/sales | 98.22% | 88.85% | 82.92% | 90.44% | 79.45% | 83.17% |

| Liquidity: | ||||||

| Current ratio | 183.29% | 192.95% | 187.76% | 169.52% | 175.37% | 182.84% |

| Quick ratio | 92.48% | 94.32% | 84.97% | 61.87% | 60.84% | 63.93% |

| Leverage: | ||||||

| Debt/TA | 35.90% | 32.66% | 27.03% | 31.29% | 33.55% | 30.77% |

| Debt (debt + equity) | 47.34% | 43.75% | 41.81% | 49.10% | 51.08% | 46.90% |

| EBIT/interest | 137.57% | 291.08% | 404.54% | 314.22% | 270.59% | 385.62% |

| 1977 | 1978 | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | |

| Profitability: | ||||||

| Sales growth | 1.21% | −6.21% | 13.00% | 5.35% | −15.51% | −22.23% |

| ROA (NI/TAbeginning-year*) | 1.42% | −10.12% | 1.43% | −8.20% | −6.88% | −16.51% |

| ROE (NI/OEbeginning-year*) | 4.07% | −32.53% | 6.82% | −38.95% | −55.17% | −72.53% |

| Profit margin | 1.17% | −9.97% | 1.24% | −7.19% | −7.36% | −20.08% |

| Activity: | ||||||

| Accounts receivable/sales | 19.34% | 21.16% | 24.59% | 30.91% | 35.99% | 32.60% |

| Inventory/sales | 40.49% | 41.19% | 36.92% | 31.57% | 28.23% | 30.41% |

| Net PP&E/sales | 21.18% | 22.89% | 19.13% | 15.59% | 15.41% | 16.28% |

| Total assets/sales | 92.46% | 97.81% | 92.35% | 90.37% | 94.60% | 100.54% |

| Liquidity: | ||||||

| Current ratio | 164.80% | 133.24% | 128.23% | 111.23% | 217.85% | 196.93% |

| Quick ratio | 51.62% | 44.74% | 49.57% | 54.10% | 120.60% | 104.47% |

| Leverage: | ||||||

| Debt/TA | 37.07% | 43.88% | 43.56% | 57.85% | 47.81% | 56.93% |

| Debt (debt + equity) | 54.38% | 67.59% | 67.41% | 82.26% | 67.75% | 83.27% |

| EBIT/interest | 141.92% | −132.17% | 142.02% | −44.43% | −125.79% | −290.95% |