CHAPTER 1

Introduction

This book is a basic corporate finance text but unique in the way the subject is presented. The book's format involves asking a series of increasingly detailed questions about corporate finance decisions and then answering them with conceptual insights and specific numerical examples.

The book is structured around real-world decisions that a chief financial officer (CFO) must make: how firms obtain and use capital. The primary functions of corporate finance can be categorized into three main tasks:

- How to make good investment decisions

- How to make good financing decisions

- How to manage the firm's cash flows while doing the first two

Taking the last point first, cash is essential to a firm's survival. In fact, cash flow is much more important than earnings. A firm can survive bad products, ineffective marketing, and weak or even negative earnings and stay in business as long as it has cash flow. Not running out of cash is an essential part of corporate finance. It requires understanding and forecasting the nature and timing of a firm's cash flows. For example, at the turn of the century, dot-coms were almost all losing large sums of money. However, financial analysts covering these firms focused primarily not on earnings but on what is called “burn rates” (i.e., the rate at which a firm uses up or “burns” cash). There is an old saying in finance: “You buy champagne with your earnings, and you buy beer with your cash.” Cash is the day-to-day lifeblood of a firm. Another way to say this is that cash is like air, and earnings are like food. Although an organization needs both to survive, it can exist for a while without earnings but will die quickly without cash.

Turning to the first point, making good investment decisions means deciding where the firm should put (invest) its cash, that is, in what projects or products it should invest or produce. Investment decisions must answer this question: What are the future cash flows that result from current investment decisions?

Finally, making good financing decisions means deciding where the firm should obtain the cash for its investments. Financing decisions take the firm's investment decisions as a given and examine questions like: How should those investments be financed? Can value be created from the right-hand side of the Balance Sheet?

Thus, the CFO essentially does two things all day long with one constraint: make good investment decisions and make good financing decisions, while ensuring the firm does not run out of cash in between.

TWO MARKETS: PRODUCT AND CAPITAL

Every firm operates in two primary markets: the product market and the capital market. Firms can make money in either market. Most people understand a firm's role in the product market: to produce and sell goods or services at a price above cost. In contrast, the role of a firm in the capital markets is less well understood: to raise and invest funds to directly facilitate its activities in the product market.

When people think about capital markets, they typically focus on securities exchanges such as those for stocks, bonds, and options. However, this is only the supply side of capital markets. The other side is comprised of the users of capital: the firms themselves.

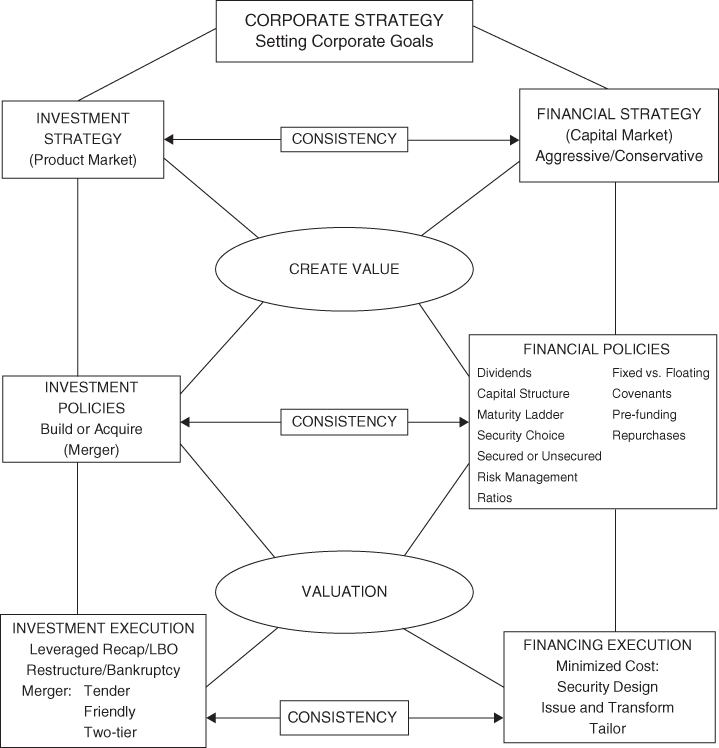

A crucial lesson when doing corporate finance is that financial strategy and product market strategy need to be consistent with one another. In addition, corporate finance spans both the product market through its investment decisions and the capital market through its financing decisions. When thinking about corporate finance, a firm must first determine its product market goals. Only then, once the product market goals are set, can management set its financial strategy and determine its financial policies.

Financial policies include the capital structure decision (i.e., the level of debt financing), the term structure of debt, the amount of secured and unsecured debt, whether the debt will have fixed or floating rates, the covenants attached to the debt, the amount (if any) of dividends it will pay, the amount and timing of equity issues and stock repurchases, and so on. Likewise, the firm's investment policies (e.g., to build or acquire, to do a leveraged buyout, a restructuring, a tender, a merger, etc.) are set in concert with the firm's product market strategy.

While it is critical for a firm to have a good product market strategy, its financial operations can also clearly add or destroy value. Value is created through the exploitation of a market imperfection in one of two markets:

- Product market imperfections include entry barriers, costs advantages, patents, and so on.

- Capital market imperfections involve financing at below-market rates, using innovative securities, reaching new investing clienteles, and the like.

In addition, the act of running the firm well can create or destroy value. Thus, we add point three:

- Managerial market imperfections include such considerations as agency costs (costs arising from the separation of ownership and control) and managers who are not doing a good job or self-dealing.

Without imperfections, there really is no corporate finance (a point we will explain in Chapter 6).

THE BASICS: TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES

This book teaches the basic tools and techniques of corporate finance, what they are, and how to apply them. It is, in football parlance, all about blocking and tackling. For example, ratios and working capital management are used as diagnostics as well as in the development of pro forma Income Statements and Balance Sheets, which are the backbone of valuation. It is not possible to do valuations without being able to do pro formas. This book will show readers how to determine financing needs, how to generate estimated cash flows, and then how to estimate the appropriate discount rate to convert the cash flows into a net present value.

Chapters 2 through 4 discuss cash flow management, which is essentially how to ensure the firm does not run out of cash. Cash flow management is necessary to evaluate the financial health of a firm, forecast financing needs, and value assets. The tools used in cash flow management include ratio analysis, pro forma statements, and the sources and uses of funds. This is the nitty-gritty of finance: managing and forecasting cash flows.

Chapters 5 through 13 examine how firms make good financing decisions. That is, how a firm should choose its capital structure and the trade-offs of the various financing alternatives. We will also cover financial policies and their impact on the cost of capital. These chapters will answer a number of questions, including: Can firms create value with their choice of financing? Is one type of financing superior to another? Should the firm use debt or equity? If the firm uses debt, should it be obtained from a bank or from the capital markets? Should it be short-term or long-term debt, convertible, callable? If the firm issues equity, should it be common stock or preferred stock? When should a firm restructure its liabilities and how?

Chapters 14 through 17 illustrate how firms make good investment decisions. The tools and techniques to value investment projects will be covered in depth, including the determination of the relevant cash flows and the appropriate discount rate. These tools and techniques will then be used to value projects and firms.

There are only five main techniques to value anything, four of which will be covered in this book (real options, the fifth method, will be covered only superficially because this technique is infrequently used and requires knowledge of options and mathematics beyond the scope of this book). This book will cover many different ways to value a firm or project within four main families or techniques. For example, discounted cash flow techniques include free cash flows to the firm with a weighted average cost of capital, using a free cash flow to equity discounted at the cost of equity, as well as calculating an adjusted present value (APV). Likewise, valuation multiples include using the price-to-earnings ratio (P/E), earnings before interest and tax (EBIT), and earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA), all of which are in the same family. The focus of the book is not only to teach the techniques but also to provide an understanding of the logic behind each method and to give readers the ability to translate from one valuation method to another.

Chapters 18 through 22 cover leveraged buyouts (LBOs), private equity, restructuring, bankruptcies, and mergers and acquisitions, all of which combine investment and financing decisions. These five chapters will use two comprehensive examples to cover the issues in depth.

Chapter 23 provides a review along with some of the authors' thoughts on both finance and life.

A DIAGRAM OF CORPORATE FINANCE

Figure 1.1 provides a schematic diagram of how your authors view corporate finance. Corporate finance begins with corporate strategy, which dictates both investment strategy and financial strategy. These strategies lead to investment and financial policies that ultimately have to be executed. We will emphasize many times in this book that there must be consistency between every level of this diagram. In addition, the investment and financial strategies and policies can create or destroy value for the firm. This book will cover the top three levels of Figure 1.1, illustrating the firm's financial strategies and policies.

FIGURE 1.1 Schematic of Corporate Finance

A BRIEF HISTORY OF MODERN FINANCE

Finance has changed a lot over the past 60 years, probably more than any other part of business schools' curricula. Modern finance really begins with Irving Fisher,1 who developed the use of present values in 1907, though the concept did not gain widespread dissemination in finance textbooks until the early 1950s. Another major advance in finance occurred in 1952 when Harry Markowitz2 developed portfolio theory, for which he won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1990. Portfolio theory shows that diversification can reduce risk without reducing expected return. It is the theoretical basis for the mutual fund industry, which grew dramatically in the 1950s and 1960s.

Finance began to move away from payback as the principal technique to evaluate investments in the 1950s. Internal Rate of Return (IRR) and Net Present Value (NPV) took over as the primary ways to value investment decisions. The profession also moved away from believing earnings were of utmost importance. Today we know it is cash flows, not earnings, that matter most.

Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller (M&M) with their papers in 1958, 1961, and 1963 gave birth to modern corporate finance, which is the focus of this book. (Modigliani was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1985 for this and other work, while Miller was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1990 for this work.) M&M showed that under certain key assumptions, neither capital structure (1958) nor dividends (1961) mattered. In 1963, M&M relaxed their no-tax assumption and then capital structure mattered.

Other notable work we will call on in this book is that of Eugene Fama,3 who developed the concept of efficient markets in the 1960s (and won the Nobel Prize in 2013). His idea was that markets rapidly incorporate and price information. This concept was the demise of technical analysis, which still exists but has only a fringe following today.

Another major development in the 1960s was the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) created by William Sharpe and John Lintner. (Sharpe won the Nobel Prize in 1990 for this work. Lintner would have almost certainly shared the prize had he still been alive, but the Nobel is not awarded posthumously.4) The CAPM dramatically changed how we measure the performance of the stock market and other investments.

The next notable advance was the work done by Fischer Black, Myron Scholes, and Robert Merton on option pricing in the early 1970s. (Scholes and Merton received the Nobel Prize in 1997. Black died in 1995.) The extensive number of options trading today is based on this work.

Focusing specifically now on corporate finance, the M&M papers from 1958 to 1963 began to be modified and extended in the 1980s. Corporate finance theory moved beyond M&M by including elements such as asymmetric information, agency costs, and signaling. Theories developed in which capital structure and dividends did indeed matter. The interaction and dynamics between financing and investment decisions also became the subject of study.

More recently, finance has looked at the impact of human behavior in financial decisions. This is called behavioral finance, for which Richard Thaler won the 2017 Noble Prize, and returns to the question of whether markets are truly efficient and how individual behavior affects financial decisions.

On the institutional side, there were dramatic changes in the laws and institutions affecting corporate finance. In particular, regulations regarding new financing and commission rates on buying and selling equities dramatically changed corporate financing. For example, shelf registrations made the use of selling syndicates less common and underwriting far more competitive, so the number of investment banks dropped by more than half. At the same time, the size of the remaining major investment banks grew substantially.

The rise of the junk bond market began in 1988 and extended through the 1990s. Prior to 1988 it was virtually impossible to issue debt that was not investment grade (BBB or better). Lower-rated debt existed, but this was debt that had been investment grade when issued and had become riskier as the firm's financial situation deteriorated. (This risky debt was called “fallen angels.”) Michael Milken at the investment bank Drexel Burnham Lambert created a market where lower-rated (high-yield or “junk”) debt could be issued. This type of debt was used primarily to finance takeovers and start-ups. This dramatically changed the nature of corporate control as well.

The 1990s also saw the rise of hedge funds, the rapid increase of short sales, and a “stock market bubble” based on the overvaluation of dot-coms. The passage and adoption of the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010 has had and will continue to have a major impact on financial structures and practices. Most recently, the Jobs and Tax Cuts Act of 2018 was passed in December 2017. This was the most significant change to corporate tax law in at least 50 years. It not only reduced the maximum corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, but it also limited the tax deductibility of interest and changed how capital expenditures are depreciated.

What is the next best big thing in finance? We wish we knew. New knowledge is rarely predictable.

READING THIS BOOK

While someone with no business background can read this book, it is designed for those with some prior knowledge of basic finance and accounting and will be much easier to read for that audience.

This book is written in a conversational format and uses a case-teaching, inductive approach. That is, examples are used to illustrate theory. While simply stating the theory as in a lecture format may be more direct, the use of examples provides the reader with a better understanding of the problem.

The footnotes don't have to be read the first time through a chapter, but they are meant to be read. They add important caveats, details, occasional humor, and examples of alternative ways to do the calculations in this book.

Repetition is an important part of learning any material and is an important part of this book. To that end, the tools and concepts in this book will be presented repeatedly, albeit in new and different situations. For example, ratio analysis, presented in the next chapter, will be used throughout the book. Every important topic will be mentioned several times in different contexts.

The material may seem difficult and even frustrating at first, but as readers proceed through the text, it will appear to slow down and come together. By the end of the book, readers should be able to understand how firms set financial policies and how valuation and investing is done in finance (e.g., read an investment bank valuation and understand the assumptions that were made, what is hidden, and what is not).

Like much in life, the best way to learn something is by doing it. Reading about how finance should and should not be done can teach up to a point. However, to really be able to do something yourself requires actually doing it. To that end, the reader is strongly encouraged to work through all the detailed examples and cases given in the book.

One brief comment on computer spreadsheets. The use of computer spreadsheets is very common today due to their facilitation in processing large quantities of data and their flexibility in allowing the user to change one item and see the impact elsewhere. Unfortunately, the use of computer spreadsheets often causes the user to lose any sense of the underlying assumptions. For this reason, it is often useful to fall back on paper and pencil when doing an analysis for the first time.

Finally, in most situations there are definite wrong answers, but there is generally more than one right answer.

After reading the book, we hope you will have enjoyed yourself and learned a lot of finance.

Welcome aboard!