CHAPTER 13

Restructuring and Bankruptcy: When Things Go Wrong (Avaya Holdings)

This chapter will discuss how firms resolve financial distress. Chapter 5, which discussed Massey Ferguson, gave a broad overview of what happens to a firm when it gets into trouble because cash flows are insufficient to meet its required interest and principal debt payments. Massey Ferguson had profitable operations but inconsistent financial policies and a much more levered capital structure (i.e., much more debt) than its competitors. When an economic downturn occurred, Massey Ferguson was unable to pay its debts and was forced to restructure. Its product market position never recovered, and the firm eventually sold its operations.

The purpose of Chapter 5 was to show you that finance matters. It was our introduction to a firm's financial policies and provided a general overview of financial distress. It was not meant to discuss financial distress in detail. This chapter covers how a firm and its creditors operate in financial distress. A firm's actions in financial distress are guided by economics as well as very specific laws on reorganization and bankruptcy.

In this chapter we will use Avaya Holdings Ltd. (AVYA), a 2017 bankruptcy, to illustrate the restructuring and bankruptcy process. We will use this case to discuss the theory and the rules regarding financial distress.

WHEN THINGS GO WRONG

When is a firm in financial distress? Financial distress occurs when a firm is unable to meet its financial obligations (e.g., the firm does not pay its debt holders their interest or principal as contractually agreed) and/or when the value of a firm's liabilities exceeds the value of its assets. Financial distress can result from product market and/or financial market failure. As stated earlier in the book, every firm operates in both the product market and the financial market. Product market failures occur when a change in market conditions (e.g., a drop in demand, a new competitor, higher costs, or a new product) create a loss in a firm's operations. An example, mentioned earlier, is how Kodak's film and film processing were displaced by digital photography. Financial market failures occur when a firm has the wrong financial policies, in particular the wrong capital structure (as we saw with Massey Ferguson, a firm that had profitable operations but too much debt).

Avaya Holdings is an example of a firm that had both product market and financial market problems. As a result, the firm experienced financial distress and filed for bankruptcy. Avaya emerged from bankruptcy within a year.

Avaya Holdings

Avaya, a “global business communications company,” provides hardware and software for call centers, video messaging, networking, and services. The firm is a 2000 public spin-off from Lucent Technologies, which was itself a 1996 spin-off from AT&T. (Lucent combines parts of Western Electric and Bell Labs, both previously part of AT&T.) Avaya's two main competitors are Microsoft Corp and Cisco Systems Inc.

How was the firm doing? Table 13.1 provides selected Avaya Income Statement and Balance Sheet information from 2004 through 2007. As can be seen from the table, in 2004 Avaya had operating income of $323 million, with net income of $291 million on revenues of $4.1 billion. In 2007, operating income was $266 million and net income was $215 million on revenues of $5.3 billion. On the financing side, Avaya started with a very low amount of interest-bearing debt in 2004 (only $593 million, which was 14.3% of total assets) and had none from 2005 through 2007.1

TABLE 13.1 Avaya's Selected Financial Information 2004–2007

| ($ millions) | 9/30/2004 | 9/30/2005 | 9/30/2006 | 9/30/2007 |

| Products | 2,048 | 2,294 | 2,510 | 2,882 |

| Services | 2,021 | 2,608 | 2,638 | 2,396 |

| Total sales | 4,069 | 4,902 | 5,148 | 5,278 |

| Product costs | 928 | 1,049 | 1,168 | 1,295 |

| Amortization of technology | 1,196 | 1,297 | 1,320 | 20 |

| Services | — | 259 | 270 | 1,512 |

| Total direct costs | 2,124 | 2,605 | 2,758 | 2,827 |

| Gross profit | 1,945 | 2,297 | 2,390 | 2,451 |

| Selling, general & administrative | 1,274 | 1,583 | 1,595 | 1,552 |

| Research & development | 348 | 394 | 428 | 444 |

| Amortization of intangibles | — | 22 | 104 | 48 |

| Goodwill & intangible impairment | — | — | — | 36 |

| Restructuring, net | — | — | — | 105 |

| Total operating costs | 1,622 | 1,999 | 2,127 | 2,185 |

| Operating income (EBIT) | 323 | 298 | 263 | 266 |

| Interest expense & other | 66 | 19 | 3 | 1 |

| Other income (expense) | (15) | (32) | 24 | 43 |

| Profit before tax | 242 | 247 | 284 | 308 |

| Income tax (benefit) | (49) | (676) | 83 | 93 |

| Net profit | 291 | 923 | 201 | 215 |

| Depreciation & amortization | 272 | 272 | 269 | 291 |

| EBITDA | 595 | 570 | 532 | 557 |

| Total assets | 4,159 | 5,219 | 5,200 | 5,933 |

| Total interest-bearing debt | 593 | — | — | — |

| Total equity | 794 | 1,961 | 2,086 | 2,586 |

This combination of low debt and stable cash flows made Avaya an attractive takeover target. (What makes a good takeover target will be discussed later in the book.) In October 2007, Avaya was in fact purchased by TPG Capital and Silver Lake Partners (two private equity firms) for $8.2 billion.2 The new owners planned to increase Avaya's cash flows by reducing costs and growing the call-center software portion of the business. Using Avaya's strong financial position and projected cash flows, the private equity firms were able to borrow $5.8 billion to help pay for their purchase of Avaya.

The $8.2 billion purchase of Avaya by TPG Capital and Silver Lake Partners was funded as follows:

| (in millions) | |

| Senior secured asset-based revolving credit facility | $ 335 |

| Senior secured term loan (maturing in 2014) | $3,800 |

| Senior secured multi-currency revolver | $ 200 |

| Senior unsecured cash-pay loans (maturing in 2015) | $ 700 |

| Senior PIK toggle loans (maturing in 2015) | $ 750 |

| Total debt | $5,785 |

| Equity investment | $2,441 |

| Total purchase amount | $8,226 |

Avaya became a private firm after it was purchased and was delisted from the NYSE in October 2007.

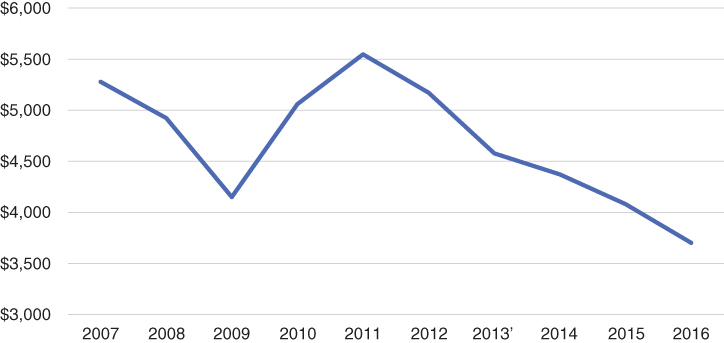

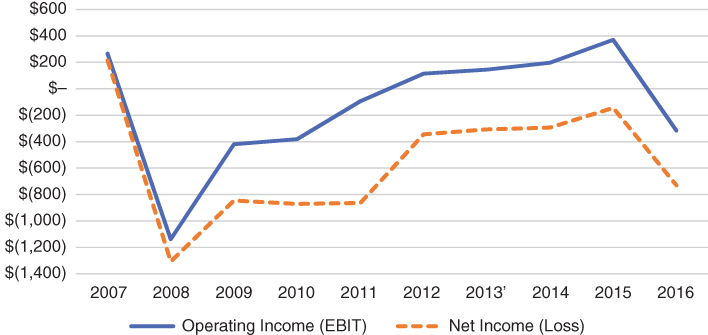

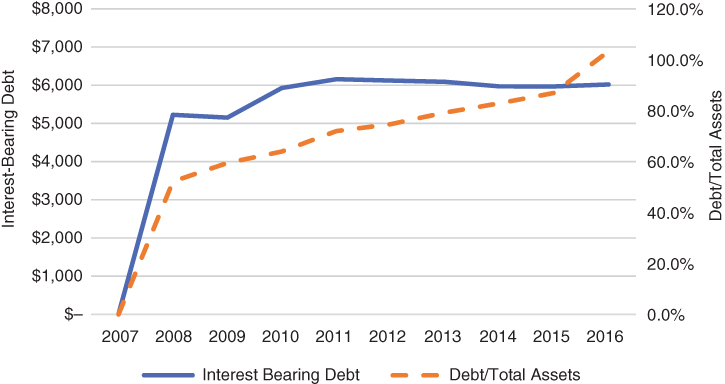

What happened next? Well, this is a chapter on financial distress. Unfortunately, sometimes things go wrong even when firms carefully plan for the future, do pro formas, and forecast future cash flows. This happens even when firms have the right financial policies, though it happens more often with the wrong financial policies. Figure 13.1 plots Avaya's revenue, while Figure 13.2 plots Avaya's operating income (EBIT) and net income/loss for 2007–2016, the period during which Avaya was a private firm. Figure 13.3 plots Avaya's total debt and debt-to-total-asset ratio over the same period.

FIGURE 13.1 Avaya Revenue ($ millions)

FIGURE 13.2 Avaya's Operating Income (EBIT) and Net Income (Loss) ($ millions)

FIGURE 13.3 Avaya's Interest Bearing Debt ($ Millions) and Avaya's Debt/Total Assets

The global financial crisis that started in late 2007 negatively impacted Avaya's operations. In addition, its product market results were affected by a shift from hardware- to software-intensive call centers. Furthermore, its two main competitors, Cisco and Microsoft, went after Avaya's customers by offering them more services and better prices.3 In 2009, Avaya incurred a loss of $845 million instead of its projected net income of $418 million. Figure 13.1 shows that Avaya's revenue fell by 6.7% in 2008 and then by an additional 15.7% in 2009. As the economy recovered, Avaya's revenue rebounded in 2010 and 2011 but then declined through 2016.

As shown in Figure 13.2, after an initial decline in operating and net income in 2008, Avaya managed to improve its operating income from a loss of $1.1 billion in 2008 to annual profits from 2012 to 2015. In 2015 operating income was a positive $371 million. Over the same period, Avaya's net income improved from a loss of $1.3 billion in 2008 to a loss of $144 million in 2015. (Most of the reason that operating income was positive yet net income was negative is due to Avaya's interest expenses.) In 2016, as revenue continued to fall, Avaya's operating income once again turned negative. (Revenue fell to $1.8 billion, operating losses were $316 million, and net income was negative $730 million.)

On the financing side, as seen in Figure 13.3, the debt level for Avaya changed dramatically in 2008 due to the takeover. Avaya had no debt in 2007, but its debt increased by $5.2 billion due to the takeover as TPG Capital and Silver Lake Partners largely used debt to purchase Avaya's publicly held shares. (The mechanics of how this is done will be explained further in Chapter 18.) This represented a debt-to-asset ratios of 52.2%. In contrast, Cisco's debt-to-asset ratio was 11.7% and Microsoft's was 0% (both firms had significant amounts of cash as well). Additionally, Cisco and Microsoft were much larger firms than Avaya and had substantially more diversified sources of revenue. Avaya had total assets of $10.0 billion in 2008 compared to Cisco's $58.7 billion and Microsoft's $72.8 billion.

During its period as a private company, Avaya continued to invest in operations. In 2009, it acquired Nortel Networks Corporation for $915 million, and in 2012 it acquired the videoconferencing firm Radvision for $230 million. These purchases were funded by additional debt, which explains the increased debt in fiscal 2010 seen in Figure 13.3. Despites these investments, by the end of fiscal 2016, Avaya's sales were down 29.9% from its 2007 levels.

Figure 13.3 shows that Avaya's debt level rose in 2009 to $5.9 billion (due to its two acquisitions) and the debt ratio (interest-bearing debt to total assets) rose to 59.5%. Between 2010 and 2016 the debt level remained fairly constant, but the debt-to-asset ratio rose dramatically as losses reduced the value of Avaya's assets. By 2016, the debt level was $6.0 billion and the debt ratio was 102.3%. (When the debt ratio is over 100% it means interest-bearing debt is greater than total assets.)

Thus, the combination of declining revenues and high interest payments exacerbated Avaya's financial problems (somewhat analogous to the case of Massey Ferguson). Avaya's improvements in operations were not enough to pay down its debt, but the firm's total debt level stayed roughly the same during this period 2010–2016. An additional complication was that most of the firm's initial debt came due in 2014. Avaya's initial projections was that part of this debt would be paid down and part refinanced. As seen in Figure 13.3, the pay-down did not happen, but Avaya did undertake four major refinancings over this period (in 2011, 2013, 2014, and 2015). In each of the refinancings, Avaya retired debt that was coming due and replaced it with debt with later maturities.

Avaya Files for Chapter 11 Bankruptcy

Why did Avaya file for bankruptcy?

Avaya had been making its interest payments and refinancing its debt as it matured, and its bond rating had stayed constant over the period 2007–2015 (with an average debt rating of B3 from Moody's and B- from Standard and Poor's). However, as shown in Figure 13.3, the ratio of debt to total assets went up, and Avaya's product market position declined (as measured by falling revenues). At the end of 2016, Avaya needed to refinance its debt again. Unfortunately, as mentioned above, Avaya's operations in 2016 took a sharp downward turn. Revenues fell from $4.1 billion in 2015 to $3.7 billion in 2016. More importantly, operating income turned negative and net income, which had been negative $144 million, fell to negative $730 million.

At the end of 2016 it appeared Avaya's future cash flows would be insufficient to cover its interest payments. Also, as shown in Figure 13.3, its debt level now exceeded its asset value. These results meant Avaya's ability to refinance its debt was now in doubt. Since Avaya did not have the funds to make its interest payments nor the ability to borrow new debt, the firm filed for bankruptcy (it literally ran out of cash).4

Avaya filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on January 19, 2017, listing $5.5 billion in assets and $6.3 billion in debt. The firm emerged from Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings less than a year later, on December 15, 2017, and once again become a public company (stock ticker AVYA). How this transpired is detailed below.

Avaya's product market challenges from the global financial crisis in 2007 plus competition from larger, better-financed competitors hurt its product market position and its revenue and income. Coupled with a heavy debt burden imposed by its new owners, this hamstrung the firm and pushed it into financial distress. If Avaya had never levered up, it certainly would have been much easier for the firm to survive without bankruptcy.

Now, let's move into the economics and institutional rules regarding financial distress.

THE KEY ECONOMIC PRINCIPLE OF BANKRUPTCY IS TO SAVE VIABLE FIRMS

When should we save a firm in financial distress? Or to put it another way, when should we liquidate a firm in financial distress? Many people think bankruptcy signals an end to a firm's operations. Sometimes it does, but that isn't necessarily the actual or the optimal outcome. This is particularly true if a bankruptcy is caused by incorrect financial policies instead of product market failure.

Most people understand that financial distress can occur because of product market issues (e.g., when there are better or cheaper products, as in our Kodak example). Avaya experienced some of this with a decline in hardware sales, the downturn in the economy, and increased competition from Microsoft and Cisco. If operations become unprofitable, a firm must solve its product market problems to stay in business. This usually involves cutting segments of the firm that are unprofitable, selling assets, and reducing costs. Sometimes this works and at least part of the firm's operations continue. Sometimes it does not work and the firm ceases to exist.

However, financial distress can also occur because of a firm's choice of financial policies. This was the case with Massey Ferguson, where the firm had an established position in small tractors but had too much debt when an economic downturn hit. Avaya had a similar situation after it went private and levered up: the firm could have survived its product market issues (indeed, its operating income was positive for much of the 2008–2016 period) with its old capital structure of no debt. It was the required debt obligations that pushed the firm over the line into financial distress.

Although not always true, a general rule for whether a firm should survive or not is that the firm should survive or not if it has profitable operations. In other words, independent of its capital structure, does the firm make money in the product market? Another way of saying this is: If the firm was financed with all equity, would it still be profitable?

WHEN SHOULD A FIRM FILE FOR BANKRUPTCY?

What is bankruptcy? Bankruptcy is a legal process that institutes an automatic stay (i.e., a legal action that stops creditors from collecting) on all claims against the firm. This includes both interest and principal payments to debt holders. Bankruptcy also initiates a court-supervised procedure that alters the claims on a firm. Essentially, it stops payments to creditors and reassigns who gets the operating cash flows. How does bankruptcy help? If the firm's cash flow obligations are reduced enough, particularly to the debt holders, the value of the firm may become positive. Is it necessary to declare bankruptcy to do this? No, a firm can restructure by getting its claimants to voluntarily change their claims instead. If a firm can complete a voluntary restructuring, there is usually no need for bankruptcy. In an M&M world (with zero transaction costs, no costs of financial distress, zero taxes, no information asymmetries, and efficient markets), claims on the firm would be revalued by the claimholders simply and costlessly.5 However, we know that the M&M world is not realistic and that restructurings are not costless.

What prevents firms from always restructuring their debt outside of bankruptcy? While many firms do reorganize outside of bankruptcy (e.g., covenants are often modified, missed payments ignored, etc.), there are two key obstacles. The first is getting everyone to agree, and the second is taxes.

There are economic incentives in some situations for creditors to “hold out” and not participate in a restructuring. That is, if all the creditors but one agree to a reduced repayment (below their debt's contractual value), then the one creditor who does not agree (i.e., holds out) may receive full payment while the others get less.6

For example, assume a firm has 100 debt holders with claims of $1 million each for a total of $100 million. Further assume that due to changes in the product market, the value of the firm is now only $80.2 million. The firm offers each claimholder new debt worth $800,000 for a total of $80 million. If 99 debt holders agree to the exchange and one does not, those who agree get new claims worth $800,000 and the one who holds out retains their original claim worth $1 million (for a total of $80.2 million). Understandably, many debt holders may do this calculation simultaneously, so instead of one holdout there may be many, at which point the exchange offer fails.

So, can't we get enough reasonable claimants to constitute a majority vote and then force everyone to accept the same deal? No. Even with a majority, we can't force everyone to accept the exchange, at least not outside of bankruptcy. Why not? In the U.S., the Trust and Indenture Act of 1939 prohibits altering the principal, interest, or maturity of public debt without unanimous consent. Thus, even one holdout can scuttle a potential deal outside of bankruptcy.

Another incentive for holdouts during restructurings emerged after the 1986 bankruptcy case of LTV Corporation. In this case, the firm filed for bankruptcy after a reorganization had occurred. During the bankruptcy process, the judge ruled that debtors who had previously exchanged (i.e., swapped their old debt for new debt with a lower value) could only claim the “reorganized” debt's value instead of the face amount they had been owed prior to the reorganization agreement. The holdouts who had not swapped old debt for new debt of reduced value kept their original and higher-valued claim during bankruptcy proceedings. Since this 1986 case, claimants have worried that if they participate in a restructuring, they will end up with a reduced claim if a bankruptcy is later filed. This increases their incentive to hold out.

The second key obstacle to restructuring is taxes. Section 108 of the IRS tax code says that cancellation of debt (outside of bankruptcy) must be immediately recognized as income. Thus, a financially distressed firm with insufficient cash may have a tax bill to pay if it restructures its debt. (In our example above, the value of the debt goes from $100 million to $80.2 million, and this would generate $19.8 million of taxable income.)7

Restructuring is costly, and in some cases the holdout problem or the tax indebtedness problem may prevent a negotiated solution. So, what if a firm can't overcome the holdout problem or the tax consequences? The firm still has the option to file for bankruptcy. Bankruptcy takes care of both the holdout and tax problems. In bankruptcy, the Trust and Indenture Act does not hold. A large enough majority of debt holders (how large is defined below) can force all claimants in a class to accept the negotiated settlement. Furthermore, cancellation of debt is not a taxable event in bankruptcy.

Bankruptcy, however, is costly in its own way. Chapter 6 reviewed the empirical evidence that direct bankruptcy costs (e.g., the costs of lawyers, accountants, and courts) are 2–5% of total firm value for large (Fortune 500) companies and might be 20–25% for medium-sized (mid-cap) firms. In addition, the indirect costs of financial distress can be much higher (e.g., lost customers, suppliers, employees, and business opportunities; management focused on saving the firm rather than competing in the marketplace). Thus, there is still an incentive to try to find a solution outside of bankruptcy.

Is there any other way to reduce the costs of reorganization other than restructuring or bankruptcy? Yes, there is another way to reorganize that is partly in and partly outside of bankruptcy. It is called a “prepackaged” bankruptcy. This is done by negotiating (like a restructuring) prior to filing for bankruptcy and then filing for bankruptcy with the already negotiated reorganization plan. This prevents any holdout creditors from scuttling the reorganization because the bankruptcy filing forces them to accept the plan already agreed upon by other creditors. It also allows the firm to exit bankruptcy almost as quickly as it entered. It is essentially a restructuring that does not require unanimity and avoids the taxation of income that occurs with cancellation of debt.

There are costs to prepackaged bankruptcies as well. First, a firm must have sufficient cash flows to continue operations and pay its debt obligations during the negotiations. This means the firm must recognize the probability of financial distress before the situation becomes too dire. Sometimes management is reluctant to recognize a firm's developing problems; other times the problems are sudden and unanticipated. Second, there is no automatic stay during the negotiations, which means some creditors, alerted to the possibility of distress by the negotiations, may try to enforce their claims during the process. Third, unsecured claims (e.g., trade, leases, employee/union) are often difficult to identify outside of bankruptcy. Only after filing for bankruptcy will all the claims be known.8 Nonetheless, prepackaged bankruptcies can be beneficial in lowering costs by avoiding a protracted bankruptcy process.

THE RULES OF BANKRUPTCY

The U.S. bankruptcy code has two main types of corporate bankruptcy: Chapter 7 and Chapter 119 (so called as they refer to specific chapters in the bankruptcy code).10 Chapter 7 oversees the orderly liquidation of a firm in which the assets are sold (piecemeal or as a whole). This is the desired solution if the value of the assets in liquidation are greater than the value of the assets in ongoing operations. It is often the result of product market problems that can't be fixed. In Chapter 7 bankruptcies, creditors are repaid in the order of their priority ranking (e.g., first secured debt, second secured debt, unsecured debt, and then equity).

However, if the value of the assets in ongoing operations is greater than in a liquidation, then the firm should continue operations. Chapter 11 allows for the reorganization of a firm's claims through a negotiation among its claimants, who decide how much each claimant class will receive. The central idea in a Chapter 11 bankruptcy is to determine all the firm's liabilities, establish their priority, and create a process by which those creditors who will not be paid in full have the decision rights on whether to liquidate or allow the firm to continue operations.11 The logic is that it is those creditors whose funds are at risk are best able to determine if the firm is worth more as a going concern or not.

In the rest of this chapter, our focus is on Chapter 11 bankruptcy—that is, bankruptcies in which the value of a firm's operation is positive and the firm would be profitable if it had the correct financial policies in place.

An important point: A Chapter 11 bankruptcy does not, by itself, fix any product market issues. The bankruptcy process may result in new management, new strategies, and a repositioned firm. However, this is not the goal of bankruptcy law and will not happen naturally as part of the bankruptcy process. The bankruptcy process is designed to redistribute a firm's future cash flows by deciding which creditors get them and in what amounts. Bankruptcy law therefore only helps a firm like Avaya redistribute positive cash flow from operations.

Who runs the firm during a Chapter 11 bankruptcy? This is an important question since it helps to determine which claims will be considered valid, what changes will be made to product market operations, what changes will be made in financial policies, and who gets to first propose the reorganization plan. In many countries a trustee will be appointed by the court to oversee (and possibly replace) the firm's management. In the U.S., management is given the first chance to remain in charge (except in cases where creditors can prove fraud or gross mismanagement). Those in charge (whether current management or a trustee) have 120 days to produce a reorganization plan and then another 60 days to get claimants (those claiming they are owed funds from the firm) to approve it. The court can and often does extend this time period.

How are the validity of the financial claims filed against the bankrupt firm determined? Courts, with human judges, assess whether claims against a firm are legitimate (in addition to numerous other decisions). If judges are important, can a firm shop for a judge likely to rule in its favor? Technically, a firm has the choice to file for bankruptcy where it was incorporated, where it is domiciled, or where it has its principal place of business. This gives corporations substantial leeway in choosing a court (and thereby a judge). But do firms use the leeway they have when deciding where to file for bankruptcy? There is anecdotal evidence they do. For example, one of your co-authors documented how at one point over 30% of NYSE and ASE corporate bankruptcies were filed in the Southern District of New York even though there were 93 bankruptcy court districts at the time. (The location of these filings could not be justified by the size or complexity of the cases.12)

So, how does the bankruptcy reorganization plan get approved? As noted above, the bankrupt firm (represented by the management or a trustee) has 120 days to produce a reorganization plan and then another 60 days to get claimants (debt holders and equity holders) to approve it (though the court often extends this timeline). Approval is required from each class of claimants that will be impaired under the plan. A claimant class are all claimants who share the same legal priority (e.g., senior debt holders, subordinated debt holders, equity, etc.) In each claimant class, a majority in number (one vote per creditor or shareholder) and two-thirds by dollar amount must approve. What does all this mean? First, only creditors who are impaired get to vote. If the plan pays a claimant class in full, these claimants don't vote (they are deemed to have voted to accept the plan). Second, only those creditors who vote actually count. Third, a plan can be blocked in one of two ways: either by a majority of voters or by voters with one-third of the combined dollar value owed to the class.

Using our example above of a firm with $80.2 million in assets and 100 debt holders owed $1 million each. If everyone votes, at least 51 debt holders (a majority) holding at least $67 million in claims (two-thirds of the dollar value) must vote in favor to gain approval.13 If this happens and all other classes also vote in favor, any holdouts are forced to accept the exchange. If the debt holders' claims are not evenly distributed, it still requires a majority in number of those voting and two-thirds in dollar amount.

How does bankruptcy deal with an unconfirmed plan (i.e., a plan rejected by voters)? First, the judge may allow the creditors, rather than management, to put forward a plan. Second, the judge can approve a plan and force an agreement even when not all classes vote in favor—this is called a “cram down.” This occurs if the judge determines that claimants voting against the plan would receive less from the liquidation of the firm (whereby claimants are paid in order of their priority). In the past the process to determine whether a claimant would receive less from a liquidation was very time consuming. More recently, courts and procedures have greatly reduced the duration of the bankruptcy process.

MAINTAINING THE VALUE OF A FIRM IN BANKRUPTCY

One of the things a firm needs to do during Chapter 11 bankruptcy is maintain operations. As we noted back in Chapter 1, a key part of the CFO's job is to manage the firm's cash flows. During bankruptcy, it is not enough to stop interest and debt payments. Employees will not work if they are not getting paid, and suppliers of financially distressed firms will often stop delivery of new goods unless they receive cash on delivery. As stated above, it is also important to fix any problems in the firm's operations.

So, how does a bankrupt firm obtain the required cash to continue funding operations? Well, it helps that the firm has stopped all interest and debt payments, but this is normally insufficient to sustain the firm. The firm is still (hopefully) able to collect cash from its customers. (This can become difficult, however, because some customers may stop doing business with the firm and others may delay making payments for prior goods and services until forced to do so by a court order.) However, most bankrupt firms still need financing (i.e., they need to raise cash). Selling assets is an option, but this can take time and will impact the firm's ability to remain a going concern. Going to the debt or equity markets is normally not an option for firms about to enter or already in bankruptcy. The solution is often a unique form of financing called “debtor-in-possession financing” (DIP financing).

DIP financing is a form of debt allowed under bankruptcy law that is senior to all other debt (i.e., it has a super priority). Super priority is required for bankrupt firms to obtain financing because without it creditors would be unwilling to lend to the firm during bankruptcy. DIP financing, by definition, violates the absolute priority rule that senior secured debt is paid first, junior secured debt is paid next, and so on down to equity being paid last. For this reason, DIP financing (and the firm's use of it) is subject to court approval.

A unique element of DIP financing is that despite it being a loan to a firm in bankruptcy, the risk to the lender may not be very high given its super priority. Thus, a bankrupt firm could potentially borrow at rates below their pre-bankruptcy levels—another feature helping it to survive. (Note that not every country allows DIP financing.)

So how long does bankruptcy take? In the past, bankruptcy negotiations could take several years before a final compromise was reached. Although once approved, a bankruptcy plan is forced upon all participants, the approval process itself requires votes by each class. If lower-ranked creditor classes do not approve, this can delay a final resolution. Why would lower-ranked creditor classes not approve? They sometimes may deliberately delay by voting against a plan in order to extract concessions from senior creditors in exchange for a speedier resolution. However, this no longer occurs as frequently as in the past.

Recent research conducted by one of your authors notes, “Today … the creditors who have come to control the bankruptcy process often are secured creditors with a lien on all or almost all assets and enormous clout.”14 The result of these control changes makes the current bankruptcy process much faster than it was 20 years ago. Today even very large bankruptcy cases often require less than a year to complete, and priority of claims is generally the rule rather than the exception.

AVAYA EMERGES FROM BANKRUPTCY

Who was in charge of Avaya during its bankruptcy process? Avaya senior management was not replaced prior to or during its bankruptcy. However, as the firm emerged from bankruptcy, the CEO Kevin Kennedy (who had been in charge since 2008) was replaced by the firm's COO Jim Chirico (who had also been with Avaya since 2008).

As stated above, it is common for claimants, knowing they will not be repaid in full, to inflate the amount of what they claim a bankrupt firm owes them. This was true for Avaya. After its bankruptcy filing, Avaya received 3,600 claims for roughly $20 billion—an amount well in excess of the $6.3 billion in liabilities that Avaya actually showed in its filing. The firm disputed most of these and the court agreed and rejected many of these claims.

In its Amended Disclosure Statement dated August 7, 2017, Avaya estimated its debt obligations as follows:

| ($ millions) | |

| Administrative claims | 150.0 |

| Professional fees | 65.0 |

| Debtor-in-possession financing | 727.0 |

| Priority tax claims | 14.4 |

| First-lien claims | 4,377.6 |

| Second-lien claims | 1,440.0 |

| Pension liabilities | 1,240.3 |

| General unsecured claims | 305.0 |

| Total | 8,319.3 |

This amount includes a new line item for $727 million in debtor-in-possession financing as well as restated pension liabilities. Avaya obtained the $727 million DIP loan from Citibank at a rate of Libor + 750 basis points to continue operations during the bankruptcy (the six-month Libor rate averaged 1.475% during 2017, meaning Avaya's DIP loan carried of a rate of around 8.975%). The firm's cash from operations and DIP financing provided the liquidity for Avaya to continue operations through its bankruptcy.

What was happening on the product market side? Avaya tried to sell its contract-center business. The firm contacted 34 potential buyers and 8 provided written bids. One of the bids was for $3.9 billion but negotiations broke down. Avaya then received another bid for $3.7 billion but decided not to pursue it.15 The firm also contacted 37 potential buyers for its networking business and received four bids. The highest bidder, at $330 million, withdrew from the deal. The next highest bidder, Extreme Networks, ended up purchasing the business for $100 million.16

Avaya submitted its first reorganization plan on April 13, 2017. However, the firm was unable to obtain approval of this plan from its creditors. On September 9, 2017, the court sent the debtors and their major constituencies to mediation, which resulted in a second plan on October 24, 2017, which was approved by the creditors and the court on November 28, 2017. The confirmed plan included:

- The debtor-in-possession financing of $725 million was to be repaid in full upon the firm's emergence from bankruptcy.

- The first-lien creditors (i.e., the senior secured creditors) received $2.1 billion in cash and 99.3 million shares of common stock worth an estimated $1.6 billion in total, or 90.5% of the reorganized firm's common stock subject to a potential post-emergence dilution up to 2.55%. (This 2.55% is based on an equity incentives plan for directors, officers, and certain employees.) Thus, the first-lien creditors received roughly $3.7 billion of their $4.4 billion claim.17 This represents a return of 84.1% of the amount claimed and 86.6% of the total paid out to all claimants.

- The second-lien creditors (i.e., secured creditors who came after the first-lien creditors) received 4.4 million shares of common stock, worth an estimated $70.4 million, roughly 4% of the reorganized firm's common stock (also subject to a potential post-emergence dilution of up to 2.55%). They also received 5.6 million warrants to purchase additional shares of common stock at an exercise price of $25.55 per share.18 Thus, the second-lien creditors received roughly $70.4 million of their $1.4 billion claim. This represents a return of 5.0% of the amount claimed and 1.7% of the total paid out to all claimants.

- The general unsecured creditors had the option to receive $58 million or purchase up to 200,000 shares of common stock. (Any cash not paid to the general unsecured creditors would be paid to the first-lien creditors.) Thus, the unsecured creditors received $58.0 million of their $305 million claim. This represents a return of 19.0% of the amount claimed and 1.4% of the total paid out to all claimants.19

- The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) received $340 million in cash and 6.1 million shares of common stock worth an estimated $97.6 million (roughly 5.5% of the reorganized firm's common stock, subject to a potential 2.55% post-emergence dilution, as above). Thus, the PBGC received roughly $437.6 million of its $1.2 billion claim. This represents a return of 36.5% of the amount claimed and 10.4% of the total paid out to all claimants.20

- Pre-emergence equity—both preferred and common stock—was canceled (i.e., the old equity holders received nothing). The old shares were canceled, and new shares were authorized of 55 million preferred stock with a par value of $0.01 and 550 million shares of common stock with a par value of $0.01.

- The new (reorganized) firm obtained long-term financing of $2.9 billion due on December 15, 2024, and a revolving credit facility of $300 million due on December 15, 2022.

Additionally, the firm was expected to fully pay administrative claims of approximately $150 million, professional fees of $65 million, and priority tax claims of $14.4 million.21

Thus, as Avaya emerged from bankruptcy, it secured approximately $3 billion in new financing. In fiscal 2017, while in bankruptcy, Avaya had positive operating profits of $137 million despite an 11% ($400 million) drop in sales. The firm suffered a net loss of $182 million mainly due to interest charges of $243 million (compared to $471 million in 2016) and reorganization costs of $98 million. As of 2018, the reduction of its debt and pension obligations from the bankruptcy process is expected to improve cash flow by over $300 million going forward.

SUMMARY

Firms are subject to financial distress because of product market and/or financial market failures. Both must be fixed for the firm to survive. Product market failures typically involve a change in product market conditions (e.g., a shift in competing firms, new products, changes in costs), although they can also result from mismanagement. Financial market failures usually involve the use of incorrect financial policies, particularly capital structure policy. Financial restructuring of the firm's liabilities and Chapter 11 bankruptcy, as discussed in this chapter, are designed to fix the latter, not the former.

Key Points to Remember

Restructuring and bankruptcy reallocate the firm's cash flows and therefore change the value of the firm and the components of its debt and equity.

The decision on whether a firm should survive should be based on whether the firm, with new financial policies, is worth more as a going concern than liquidated (in other words, if the firm has a positive NPV with new financial policies).

There are three major types of restructuring used to solve financial failure:

- Voluntary restructuring. This suffers from the difficulty of getting liability holders to agree and the tax implications of debt cancellation.

- Restructuring under a Chapter 11 bankruptcy. This solves the two problems noted above but involves additional costs due to use of the legal system.

- A prepackaged bankruptcy. This is essentially a voluntary restructuring agreement filed in bankruptcy court to force compliance on holdouts, and it requires early recognition of the impending financial distress.

Coming Attractions

This ends the section of the book dedicated to financing decisions and financial policies. We now turn to valuation, or how to make good investment decisions. The next chapter introduces the main tools used in valuation: discounting and net present value (NPV).

APPENDIX 13.A: THE CREDITORS COORDINATION PROBLEM

One of the overlooked features of bankruptcy is that it mandates that everyone in the same priority class is paid equally (i.e., gets the same percentage of their claim). Without this feature, if a firm was in financial distress, creditors would have an incentive to try to get paid first. This imposes substantial monitoring costs on creditors. The phrase “first in time is first in line” was the driving factor behind many early banking crises (see the feature box for a lighthearted example). Bankruptcy law stays the creditors' individual right to collect, provides a forum for renegotiation, and guarantees the ratable distribution of asset value among creditors with the same contractual priority.