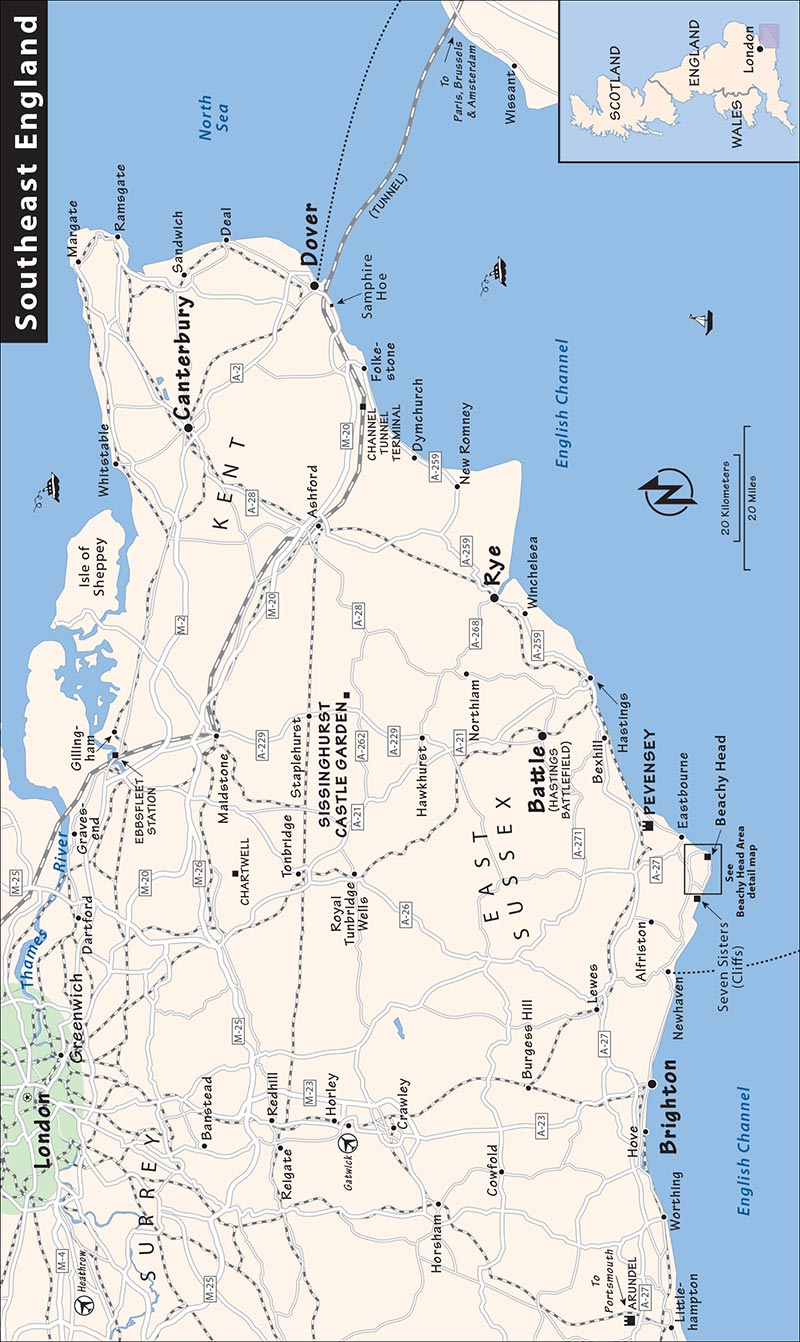

Dover • Sissinghurst • Rye • Battle Abbey and 1066 Battlefield • Pevensey Castle

Dover guards the Straits of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel. For thousands of years it’s overseen traffic between the Continent and Britain. Like much of southern England, Dover sits on a foundation of chalk. Miles of cliffs rise above the beaches, and perched above those cliffs is the impressive Dover Castle, England’s primary defensive stronghold from Roman through modern times. From the nearby port, ferries, hydrofoils, and hovercrafts shuttle people and goods back and forth across the English Channel. France is only 23 miles away—on a clear day, you can easily see it from here.

Dover’s castle is excellent, and well worth a side trip from either Canterbury (just 30 minutes away) or London (an hour away). The rest of the town, however, lacks charm—it’s a hardscrabble port that was badly disfigured by WWII Nazi shelling (from the cliffs of France, just across the Channel). And the famed “White Cliffs of Dover” are marred by industrial sprawl—they can’t hold a candle to the much more dramatic and bucolic white cliffs at Beachy Head (about a two-hour drive west, between Pevensey Castle and Brighton; see the Brighton chapter).

In the southeast English countryside near Dover, you can explore the quaint and fascinating garden at Sissinghurst, handcrafted by its larger-than-life creators; stroll the cobbles of the huggable hill town of Rye; visit the Battle of Hastings site—in the appropriately named town of Battle—where England’s future course was charted in 1066; and see the evocative ruins of a Roman and Norman fort at Pevensey.

On arrival in town (whether by car, train, or boat) head up to tour Dover Castle. Assuming you do both of the Secret Wartime Tunnel tours, plan for at least three hours. With additional time, stroll through the town center or view the White Cliffs before leaving town. If connecting Dover and towns west (such as Brighton), Battle and Rye can be visited en route (along with Pevensey Castle)—or you can take the inland route for Sissinghurst Garden.

Because of its easy access from the Continent, many travelers have a sentimental attachment to Dover as the first (or last) place they saw in England. But in recent decades—especially since the opening of the English Channel Tunnel in 1994—this workaday town has lost whatever luster it once had. Visitors should focus on a visit to the castle, standing sentry over Dover (and all of England) as it has for almost a thousand years.

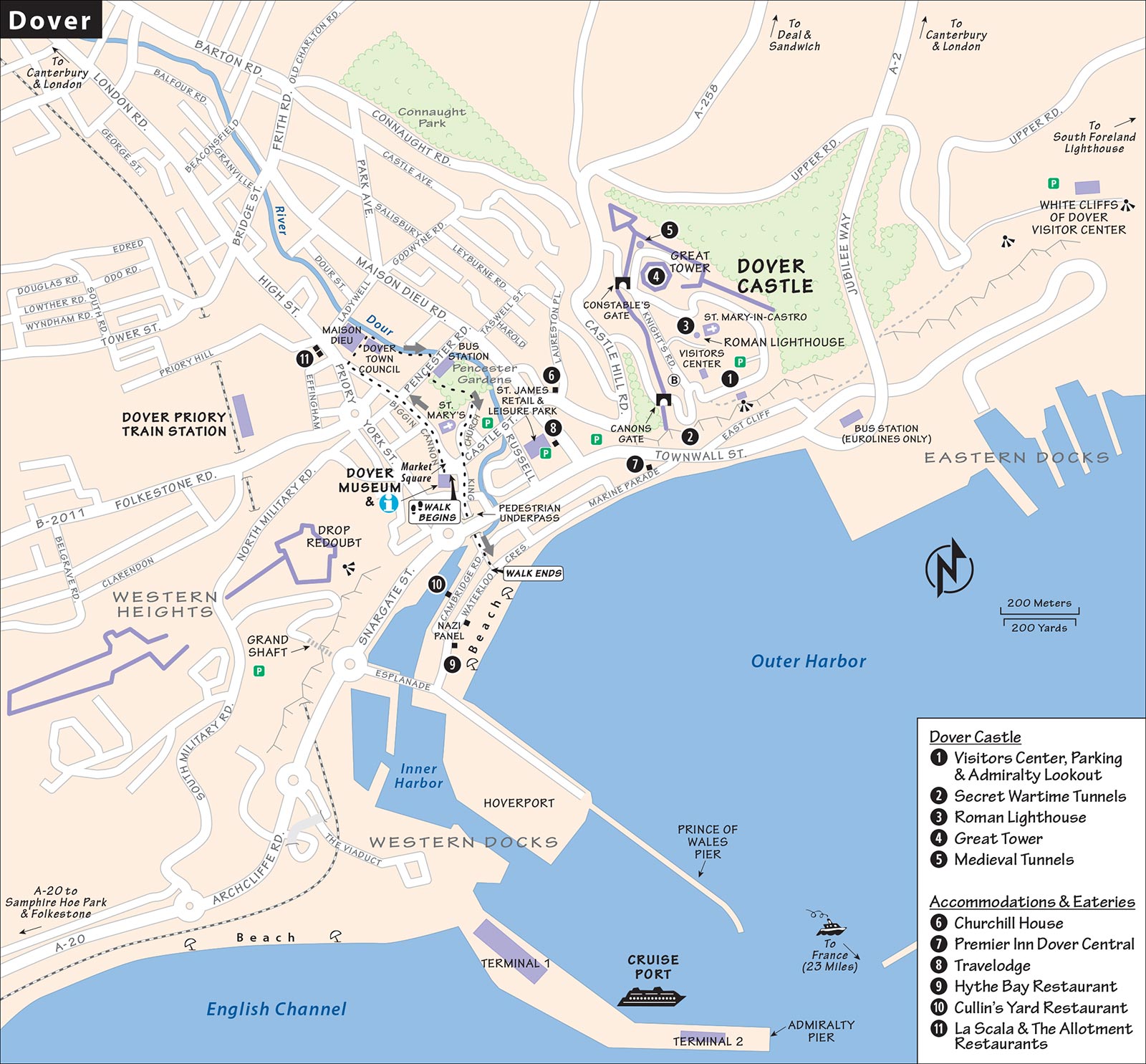

Gritty, urban-feeling Dover seems bigger than its population of 30,000. The town lies between two cliffs in a little valley carved out by its stream, the River Dour. While the streets stretch longingly toward the water, the core of the town is cut off from the harbor by the rumbling A-20 motorway and eyesore modern construction. The city center is anchored by Market Square and the mostly pedestrianized (but not particularly charming) main shopping drag. From here, an underpass leads to the beach and promenade with views of the port and the White Cliffs.

Tourist Information: Dover’s TI, in the Dover Museum on Market Square, sells ferry and long-distance bus tickets (Mon-Sat 9:30-17:00, Sun 10:00-15:00 except closed Sun in winter, Market Square, tel. 01304/201-066, www.whitecliffscountry.org.uk).

Arrival in Dover: Trains arrive on the west side of town, a five-minute walk from the main pedestrian area and the TI. Drivers find plentiful parking close to the water—follow P signs. A couple of pay-and-display parking lots are a short walk from the TI and start of my town walk: One is tucked between St. Mary’s Church and Pencester Gardens, and another is at the St. James Retail and Leisure Park (a big, modern strip mall with a handy M&S Foodhall). If you arrive by boat at the Eastern Docks, walk about 20-30 minutes along the base of the cliffs into town (with the sea on your left), or take a taxi (about £8). There is no public bus from the docks into town, but on days when a cruise ship is docked, you can take the shuttle bus (described below).

Dover is also a popular destination (and starting/ending point) for cruise ships. For information on how to connect to London from Dover’s cruise ports, see here.

Shuttle Bus: If you’re without a car, and you happen to be in town on the same day that a cruise ship is visiting, you can ride the YMS Shuttle Bus—a Smurf-blue double-decker bus that does a handy loop connecting the city center, castle, White Cliffs visitor center, and cruise port. While designed for cruisers, it’s also available to other travelers (£6 for an all-day ticket, bus departs from King Street near TI at the top of each hour, www.ymstravel.co.uk/blue-bus-company).

Dover Greeters: While the city has little meriting a guided tour, volunteer Dover Greeters are happy to walk guests through their town for an hour or two and give it a charming human dimension. This is a free service; simply arrange a meeting in advance (mobile 07712-581-557, www.dovergreeters.org.uk, dovergreeters@virginmedia.com).

▲White Cliffs of Dover Visitor Centre

Strategically located Dover Castle—considered “the key to England” by would-be invaders—perches grandly atop the White Cliffs of Dover. English troops were garrisoned within the castle’s medieval walls for almost 900 years, protecting the coast from European invaders. With a medieval Great Tower as its centerpiece and battlements that survey 360 degrees of windswept coast, Dover Castle (worth ▲▲) has undeniable majesty. While the historic parts of the castle are unexceptional, the exhibits in the WWII-era Secret Wartime Tunnels are unique and engaging—particularly the powerful, well-presented tour that tells the story of Operation Dynamo, the harrowing WWII rescue operation that saved the British Army at Dunkirk.

Cost and Hours: £20.90; daily 10:00-18:00, from 9:30 in Aug, Oct until 17:00; Nov-March Sat-Sun until 16:00, closed Mon-Fri; last entry and last tour departures one hour before closing.

Information: Tel. 01304/211-067, www.english-heritage.org.uk/dovercastle. In the middle of the complex, just below the Great Tower and near the parking lots, you’ll find a handy visitors center (ask about special events such as falconry shows, especially on summer weekends).

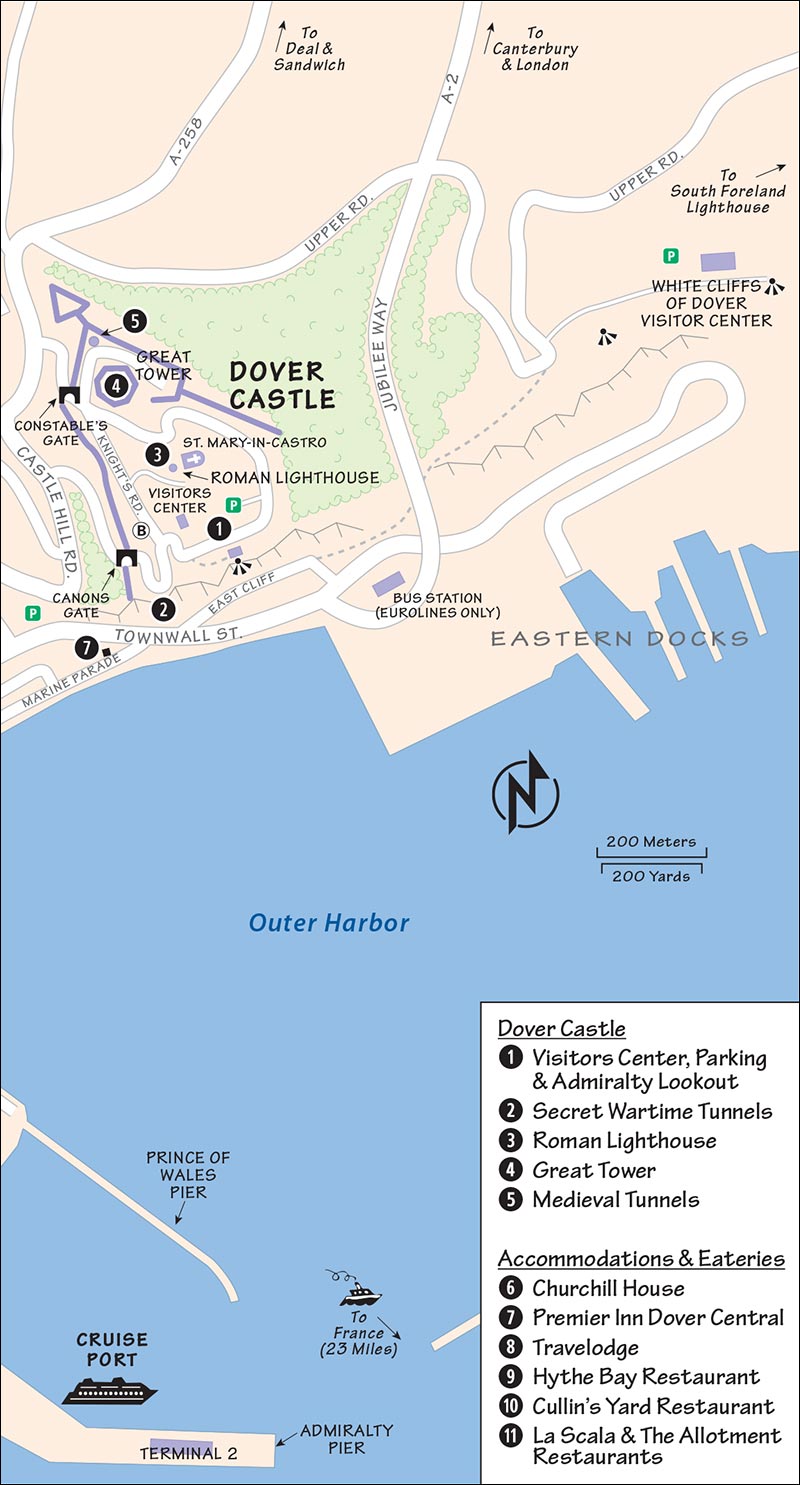

Entrances: Two entry gates have kiosks where you can buy your ticket and pick up a map. The Canons Gate (for cars or those on foot) is closer to the Secret Wartime Tunnels, at the lower end of the castle. At the top of the castle, only pedestrians can enter through the Constable’s Gate, near the Great Tower.

Crowd Alert: Summer weekends and holidays can be very crowded (especially around late morning). But the biggest potential headaches are lines for the two tours of the Secret Wartime Tunnels: the Operation Dynamo exhibit (with the longest wait) and the Underground Hospital. See “Planning Your Time,” later, for more advice on timing your tunnel visits smartly.

Getting There: Drivers follow signs to the castle from the A-20 or the town center; approaching the castle, you’ll enter the Canons Gate, buy your ticket at the booth, then loop around inside the castle grounds to reach parking lots near the visitors center. For those without a car, you can reach the castle by taxi (about £8); blue YMS Shuttle Bus, if it’s running (described earlier); or on foot (steep but manageable hike). While it’s a pretty long walk from the train station, from Market Square it’s a brisk 15-20 minutes: Go up Castle Hill Road, and about 50 yards above St. Martin’s Guesthouse look for an unmarked blacktop path on the right. As you walk in the woods, find a long set of stairs that leads to the Canons Gate ticket booth.

Planning Your Time: The key is timing the two Secret Wartime Tunnels tours—Operation Dynamo (often with a longer wait) and Underground Hospital. Each tour allows 30 people to enter at a time, with departures every 10-15 minutes. The two tours are next to each other; you’ll see a line outside each door.

If you’re early on a busy day, go directly to the Operation Dynamo tour to do it first, as it’s a better tour, sets the historical stage to help you better appreciate the hospital tour, and ends nearby, making it easy to circle back for the hospital tour (which ends higher up the hill—more logically situated for hiking up to the Great Tower afterward).

Getting Around the Castle: The free “land train” loops around the castle’s grounds about every 15 minutes, shuttling visitors between the Secret Wartime Tunnels, the entrance to the Great Tower, and the Medieval Tunnels (at the top end of the castle). Though handy for avoiding the ups and downs, nothing at the castle is more than a 10-minute walk from anything else—so you may spend more time waiting for the train than you would walking.

Armies have kept a watchful eye on this strategic lump of land since Roman times (as evidenced by the still-standing ancient lighthouse). A linchpin for English defense starting in the Middle Ages, Dover Castle was heavily used in the time of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I. After a period of decline, the castle was reinvigorated during the Napoleonic Wars and became a central command center in World War II (when naval headquarters were buried deep in the cliffside). The tunnels were also used as a hospital and triage station for injured troops. After the war, in the 1960s, the tunnels were converted into a dramatic Cold War bunker—one of 12 designated sites in the UK that would house government officials and a BBC studio in the event of nuclear war. When it became clear that even the stout cliffs of Dover couldn’t be guaranteed to stand up to a nuclear attack, Dover Castle was retired from active duty in 1984.

Self-Guided Tour

Self-Guided TourThe sights at Dover Castle basically cluster into two areas: the Secret Wartime Tunnels (with two, very different tunnel tours) and adjacent Admiralty Lookout (a WWI fire command post), both in the lower part of the castle (facing the sea); and the Great Tower and surrounding historical castle features (such as the old Roman lighthouse and the Medieval Tunnels), higher up at the hill’s summit. The castle complex is sprawling and steep, but everything is well-signed.

In the 1790s, with the threat of Napoleon looming, the castle’s fortifications were beefed up again. So many troops were stationed here that they needed to tunnel into the chalk to provide sleeping areas for up to 2,000 men. These tunnels were vastly expanded during World War II, when operations for the war effort moved into a bomb-proof, underground air-raid shelter safe from Hitler’s feared Luftwaffe. Winston Churchill watched air battles from here, while Allied commanders looked out over a battle zone nicknamed “Hellfire Corner.” Two different tours take you into the tunnels: Operation Dynamo and Underground Hospital.

Operation Dynamo Tunnel Tour: From these tunnels in May 1940, Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay oversaw the rescue mission wherein the British managed, in just 10 days, to evacuate some 338,000 Allied soldiers from the beaches of Dunkirk in Nazi-occupied France (see the sidebar). In this 45-minute tour, you’re led from room to room, where a series of well-produced audiovisual shows narrate, step-by-step, the lead-up to World War II and the exact conditions that led to the need for Operation Dynamo. You’ll hear fateful radio addresses from Neville Chamberlain and King George VI announcing the declaration of war, and watch newsreel footage of Britain preparing its war effort. Imagine learning about war in this somber way (in the days before bombastic 24-hour cable news). Sitting around an animated map, you’ll learn how Germany attacked Holland, Belgium, and France—and how the Allied troops tried to counterattack. You’ll also see how the strategic tables turned, pinning the Allies down against the English Channel. Then you’ll walk slowly down a long tunnel, as footage projected on the wall tells the stirring tale of the evacuation.

At the end of the guided portion, you’re free to explore several rooms still outfitted as they were back in World War II—such as the mapping room, repeater station, and telephone exchange.

You’ll exit onto a terrace, then enter the “Wartime Tunnels Uncovered” exhibit, which uses diaries, uniforms, archival films, and other artifacts to chart the development of the tunnels from the Napoleonic era to the Cold War.

Underground Hospital Tunnel Tour: Immediately next to the Operation Dynamo tour is the entrance to this shorter, lower-tech, 20-minute tour of the topmost levels of the tunnels, which were used during World War II as a hospital, then as a triage-type dressing station for wounded troops. Your guide leads you through the various parts of a re-created 1941 operating room and a narrow hospital ward as you listen to the story of an injured pilot of a Mosquito (a wooden bomber). Occasional smells and lighting effects enhance the tale. Finally, you’ll climb a 78-step double-helix staircase and pop out next to the Admiralty Lookout. The Underground Hospital complements the Operation Dynamo tour well.

• If you take the Underground Hospital tour, you’ll surface right next to the Admiralty Lookout; otherwise, hike up the path overlooking the sea toward the visitors center and look for the statue of an admiral standing at attention. The lookout is near the grassy slope on the seaward side of the officers’ barracks.

Admiralty Lookout: Climbing around this WWI fire command post (the only bit of WWI history in the castle), you get a great sense of guarding the Channel. The threat of aerial bombardment was new in World War I—and it became devastating just a generation later in World War II. Climb to the rooftop for the best view possible (in the castle) of the famous White Cliffs, the huge ferry terminal, and the cruise port. While you can’t see London...you can see France. The statue is of British Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, who heroically orchestrated Operation Dynamo.

• Now follow the signs to get to the Great Tower and Roman Lighthouse.

The oldest part of the vast castle complex still holds the high ground—the Great Tower and the Roman Lighthouse. Hiking up from the visitors center, you’ll come through a gate, looking straight at the Great Tower. But first, turn your attention to the hill-capping buildings on your right.

Roman Lighthouse: The round, crenellated tower is a lighthouse (pharos) likely built during the second century AD, when the Roman fleet for the colony of Britannia was based in the harbor below. To guide the boats, they burned wet wood by day (for maximum smoke), and dry wood by night (for maximum light). When the Romans finally left England 300 years later, the pharos is said to have burst into flames as the last ship departed.

The lighthouse stands within the scant remains of an 11th-century Anglo-Saxon fortress built to defend against Viking raids. Adjacent to the lighthouse is the unimpressive St. Mary-in-Castro Church (if it’s open, step inside). A surviving example of Anglo-Saxon architecture, it was built around the year 1000 and substantially restored in the 19th century. The church used the lighthouse as its bell tower.

Henry II’s Great Tower: A fortress was first built here shortly after the Battle of Hastings in 1066 (see the sidebar, later in the chapter). What you see today was finished in 1180 by King Henry II. For centuries, Dover Castle was the most secure fortress in all of England, and an important symbol of royal power on the coast.

The central building—reminiscent of the Tower of London—was the original tower (also called a “keep”). The walls are up to 20 feet thick. King Henry II slept on the top floor, surrounded by his best protection against an invading army. Imagine the attempt: As the thundering enemy cavalry makes its advance, the king’s defenders throw caltrops (four-starred metal spikes meant to cut through the horses’ hooves). His knights unsheathe their swords, and trained crossbow archers ring the tower, sending arrows into foreign armor. Later kings added buildings near the tower (along the inner bailey, which lines the keep yard) to garrison troops during wartime and to provide extra rooms for royal courtiers during peacetime. These are now filled with museum exhibits and a gift shop. On summer weekends, and for most of August, costumed actors wandering the grounds add to the fun.

Before going in the tower itself, check out some of the exhibits in the surrounding garrison buildings.

The Great Tower Story Exhibit, around to the right as you enter the courtyard, uses colorful displays and animated films to bring meaning to the place. You’ll learn how Henry II married Eleanor of Aquitaine (creating an empire that encompassed much of today’s England and France), how his heirs squandered it, and how they evolved into the Plantagenet dynasty that ruled England for some 300 years (including many of the famous Henrys and Richards).

The Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment and Queen’s Regiment Museum (next door) collects military memorabilia and tells the story of these military units, which have fought in foreign conflicts for centuries—you’ll see gritty helmet-cam footage from 21st-century deployments in Afghanistan.

Enter the tower itself (the door is a bit farther around the courtyard). The cellar, where you enter, holds the medieval kitchen and royal armory. From here, twist your way up the big spiral stairs to two more floors: a dining hall, throne room, kitchen, bedroom, and so on decorated with brightly colored furnishings. While there’s no real exhibit, docents are standing by to answer questions, and the kid-friendly furnishings give a sense of what the castle was like in the Middle Ages. In the throne room (on the second floor up), face the throne and climb up the stairs on the left to find the well—which helped make the tower even more siege-resistant. Fans of Thomas Becket can look for his chapel, a tiny sacristy called the “upper chapel” (it’s hiding down a forgotten hallway high in the building—go behind the throne, turn left, and look for the narrow hall). Climbing to the very top (about 120 stairs total) rewards you with a sweeping view of the town and sea beyond.

• Exit the keep yard at the far end through the King’s Gate. Cross a stone bridge and then descend a wooden staircase. Under these stairs is the entrance to the...

Medieval Tunnels: This system of steep tunnels was originally built in case of a siege. While enjoyable for a kid-in-a-castle experience, there’s little to see. From here, you can catch the tourist train or do the Battlements Walk. Much of Dover’s success as a defendable castle came from these unique concentric walls—the battlements—which protected the inner keep.

• Our tour of the castle is finished. For a fast return to town, exit out the Constable’s Gate near the Medieval Tunnels and follow the path steeply down.

Chalky white cliffs surround Dover on both sides for miles. From the top of the cliff, you can get sweeping views over the town (and as far as France, in clear weather). Or you can see the cliffs themselves, either from below or from an adjacent viewpoint.

The best all-around experience is the National Trust visitor center, which is on a bluff just east of town (past Dover Castle—if you’re driving to the castle, it’s an easy add-on, but non-drivers may find it’s not worth the trouble). You’ll pay a hefty parking fee to access this area, which has striking views down over Dover’s busy port (and the white cliffs just beyond it). The visitor center is just a big shop/café, with WCs and a few interpretation panels. But it’s a springboard for some enjoyable walks; see below.

Cost and Hours: Visitor Centre free; daily 10:00-17:00, off-season until 16:00; Upper Road, Langdon Cliffs, tel. 01304/207-326, www.nationaltrust.org.uk/white-cliffs-dover.

Getting There: If driving, head up the Castle Hill Road, pass the castle entrance, then take a sharp right turn onto Upper Road. After crossing over the A-2 motorway, look for the Visitor Centre entrance at the next hairpin turn (£5 parking). You can walk to the Visitor Centre from Dover, but it’s pretty far (about 2.5 miles from the train station—walk along the base of the cliffs with the sea on your right, following footpath signs from the town center). Or, if the YMS Shuttle is running, you can take it to the Visitor Centre (for cruise ship passengers; described earlier).

Scenic Walks: It’s well worth the 20-minute round-trip hike to follow the Viewpoint Walk. From the Visitor Centre, walk all the way through the parking lot and keep going. After passing through a gate, take the left (upper) trail and hike a few minutes uphill, to a viewpoint just under several communication towers (at another gate). From here, you can look back over Dover and its castle. Looking east, you’ll get a fine view of the white cliffs just beyond. To extend your hike, you can continue two miles farther along the cliff top to the South Foreland Lighthouse, built in 1846, and enjoy the glorious view (£6, possible to enter only with 30-minute tour—confirm schedule at Visitor Centre before making the trip, generally closed Tue-Thu, tea room, tel. 01304/852-463, www.nationaltrust.org.uk/south-foreland-lighthouse).

This famous cliff—opposite Dover Castle, just southwest of town—provides a sweeping view of Dover (and occasionally of France). The trail along the cliff weaves around former gun posts that were originally installed during Napoleonic times, but were used most extensively during World War II. It was here that the British military amassed huge decoy forces designed to fool the Germans into thinking that the D-Day invasion would come from Dover—across the shortest stretch of water to Calais—rather than from ports farther west and across to Normandy. Today, the bunkers are abandoned, but in decent condition; you can usually crouch through a tunnel to get a closer look at the fortress. While this site is historic, the views are not quite as good as the White Cliffs of Dover Visitor Centre described earlier, and you don’t see many white cliffs at all—just the port.

Cost and Hours: Free, open dawn until dusk, www.doverwesternheights.org.

Getting There: Drivers follow the A-20 west past the harbor to the Western Heights roundabout, take the Aycliff exit onto South Military Road, wind uphill for about a half-mile, then turn right at the small brown sign onto Drop Redoubt Road.

This park, less than two miles south of Dover, is a good stop for those who wish to see more of the white cliffs—without the industrial crush of the busy Dover docks. (It’s also handy for drivers leaving town on the A-20 toward London, since it’s an easy turn-off from the freeway.) Samphire Hoe, a chalk meadowland beneath the cliffs, was created using more than six million cubic yards of chalk left over from the construction of the Channel Tunnel in the early 1990s. What could have been a dumping ground is now a grassy expanse hosting a rich variety of plants and wildlife. The park has walking paths, an education building, and a tea kiosk, as well as a mile-long seawall that attracts anglers, wave watchers, and swimmers aiming for France. A plaque by the sea lists the names of 11 workers who died during the construction of the Channel Tunnel.

Cost and Hours: Free, pay parking, park open daily 7:00-dusk; tea kiosk daily Easter-Sept, weekends only in winter; tel. 01304/225-649, www.samphirehoe.co.uk.

Getting There: From Dover, drivers take the A-20 toward London/Folkestone and watch for the Samphire Hoe exit. After waiting for the green light at the 007-style tunnel, you’ll emerge at a pay-and-display parking lot. Walkers can follow the North Downs Way footpath, while cyclists can use the National Cycle Network Route 2; both are signposted from Dover—ask the TI for specifics.

If it’s a sunny day and you want a nice view of the cliffs and castle without heading out of town, stroll to the western end of the beachfront promenade (to the right, as you face the water), then hike out along the Prince of Wales Pier for perfect panoramas back toward the city (free, daily 8:00-dusk).

The famous White Cliffs of Dover are almost impossible to appreciate from town. A 1.5-hour White Cliffs and Beyond boat tour around the bay gives you all the photo ops you need. You’ll ride in a rigid inflatable boat that leaves from the Dover Sea Sports Centre (beach side), on the western end of the waterfront promenade (£35, 2 or more tours per day—smart to book ahead, max 12 people/boat, tel. 01304/212-880, www.doverseasafari.co.uk).

This modern and engaging museum, at the TI on Market Square, houses an amazing artifact (on the top floor): a large and well-preserved 3,500-year-old Bronze Age boat unearthed near Dover’s shoreline. Museum officials claim this is the oldest seagoing boat in existence, underlining the extremely long trading history of Dover. The boat consists of oak planks lashed together with yew twine and stuffed with moss to be watertight. You’ll also see other finds from the archaeological site, an exhibit on boat construction techniques, and a 12-minute film. Across the hall, the Dover History Gallery tells the story of how this small but strategically located town has shaped history—from Tudor times to the Napoleonic era to World War II. And back down on the ground floor are exhibits covering the Roman and Anglo-Saxon periods.

Cost and Hours: Free, Mon-Sat 9:30-17:00, Sun 10:00-15:00 except closed Sun in off-season; tel. 01304/201-066, www.dovermuseum.co.uk.

The center of Dover offers a dose of real-world England. After visiting the castle and white cliffs, those with an hour to kill can spend it taking this self-guided town walk. We’ll begin on the main square, venture up the main shopping street, and then circle around through a riverside park to the beach and promenade.

• Start in the square in front of the TI and Dover Museum.

Market Square: This marks the site of the port in Roman times. The ugly buildings all around are a reminder that the town was rebuilt after suffering major bomb damage in World War II. And the Dickens Corner building is a reminder that the great writer made many visits here. The old Georgian market building is now filled by the TI and the Dover Museum, with its 3,500-year-old Bronze Age boat (described earlier).

• Head up the street to the left of the Dickens Corner building.

Main Shopping Street (Cannon Street/Biggin Street): This mostly traffic-free axis runs north from Market Square to the Town Hall. As you walk, look up (above the dreary storefronts) to notice fine Victorian architectural details. You’ll pass St. Mary’s Church, which has a few surviving Norman parts but was largely rebuilt in Victorian Neo-Gothic. Notice its flinty stone walls. There’s plenty of flint around here—which provided some sharp weapons that helped the locals chase away the Romans when they first invaded.

Halfway down the next block on the left is the local bingo parlor (Buzz Bingo). Soft and mesmerizing bingo parlors like this make for a quirky geriatric scene nightly, and while restricted to “members only,” anyone can “join” for just the night. The regulars would love to set you up for a few games—and perhaps offer you a very cheap dinner.

Continue up a couple more blocks (through a section that permits car traffic). Re-entering the traffic-free zone of Biggin Street, on your right is a monument to locals who were lost in the two world wars (monuments like these are standard-issue in every British town). The historic buildings set back behind the monument are elegant old council offices.

The huge, looming building straight ahead is the Town Hall—also called Maison Dieu. The core of this building originated as part of a Romanesque (or “Norman”) 13th-century abbey complex, which was later seized by the government during the Reformation (16th century). For centuries it was used as a food warehouse for the Royal Navy, until it became the Town Hall in 1834. Go up the stairs facing High Street and peek into its cavernous main hall, under a hammerbeam roof.

• Walk between Maison Dieu and the war monument, and follow the walkway until you hit the little river. Then turn right again and follow the riverside path for a few blocks through the heart of the city.

River Dour: Just seven miles long but famous for its trout, this river is part of a fine greenbelt and park that splits the center of Dover. The river powered the paper mills and breweries that once stoked the local economy. To this day, beer is big in Dover, which has multiple microbreweries.

• Follow the river to, then through, a big city park (Pencester Gardens). At the end of the park, aim for the parking lot and WC, and then turn right on Church Street to circle back to Market Square. Continue downhill on King Street, through a pedestrian underpass. This “subway,” which leads to the waterfront, is decorated with a crudely painted mural of boats that have used Dover’s venerable port through the ages—from the Vikings’ longship to the hovercraft. Climbing the stairs and exiting out the far side, walk straight ahead until you hit the water.

Waterfront Promenade: Overlooking a pleasant, pebbly beach and a mighty port, this offers fine views of the castle and the white cliffs. Millions of pounds were spent to “uglify” the promenade (according to skeptical locals), but the history, memorials, and sea views make it a nice stroll anyway.

Far to the right, at the base of the pier, the clock tower with the Union Jack marks the Victorian-era customs station. This evokes the days before airplanes and undersea tunnels, when—for Brits—“going to Europe” generally meant going through Dover. Despite present-day alternatives, the English Channel still sees plenty of traffic. A ferry departs for France every hour. And more and more people are swimming the English Channel from here to Calais, 23 miles away. You can often see them training in the harbor.

Walk toward the clock tower. About two-thirds of the way there, keep a close eye along the walkway for an unusual monument displaying armored plating from Nazi gun emplacements at Calais. The Nazis shelled Dover between 1940 and 1944, discharging 84 rounds from those Calais guns. Just beyond that is a smaller monument to those lost in the evacuation from Dunkirk in 1940.

Sleeping: There’s no reason to sleep in gritty Dover, with lovely Canterbury just 30 minutes away. But in a pinch, Dover has several $$ chain hotels, including Premier Inn Dover Central and Travelodge—both near the harborfront promenade. While Dover has B&Bs, you won’t find as many here as in other English towns. One place to consider is $$ Churchill House, a comfortable, traditional type of place. Neatly run by Alex Dimech and his parents, Alastair and Betty, it’s perfectly situated, just at the base of the castle hill, with eight rooms plus a family-friendly flat (6 Castle Hill Road, tel. 01304/204-622, www.churchillguesthouse.co.uk, churchillguesthouse@gmail.com).

Eating: Your dining options in downtown Dover are few, and only a handful of places are open for dinner. My first two listings are on or near the beachfront promenade. The castle’s cafés work fine for lunch.

$$$ Hythe Bay Restaurant is your best yacht club-style restaurant. It’s literally built over the beach with a modern dining room, nice views, and a reputation for the best fish in town—including award-winning fish-and-chips (daily 12:00-21:30, The Esplanade, tel. 01304/207-740, www.hythebay.co.uk—if reserving, ask for window seat with a view).

$$$ Cullin’s Yard Restaurant is a quirky, family-friendly microbrewery with a playful, international menu ranging from pasta, salads, and panini to fish-and-chips. Choose between picnic tables on the harbor or the shipwreck interior (daily 11:00-21:30, 11 Cambridge Road, tel. 01304/211-666).

$$ La Scala, tiny and romantic, serves a good variety of Italian dishes (Mon-Sat 12:00-14:00 & 18:00-22:00, closed Sun, 19 High Street, tel. 01304/208-044).

$$ The Allotment is trying to bring class to this ruddy town, with an emphasis on locally sourced ingredients (in Brit-speak, an “allotment” is like a community garden). The rustic-chic interior feels a bit like an upscale deli, and there’s a charming patio out back. They serve a traditional afternoon tea on vintage crockery (Tue-Sat 9:00-21:30, closed Sun-Mon, 9 High Street, tel. 01304/214-467).

While the train will get you to big destinations on the South Coast, the bus has better connections to smaller towns. Stagecoach offers good one-day “Dayrider” or one-week “Megarider” tickets covering anywhere they go in southeast England (tel. 0871-200-2233, www.stagecoachbus.com).

The Dover train station is called Dover Priory. Most buses stop at the “bus station” (it’s more of a parking lot) on Pencester Road in the town center. Eurolines buses stop at the Eastern Docks, near the ferries to and from France.

From Dover by Train to: London (2/hour, 1 hour, direct to St. Pancras; also hourly, 2 hours, direct to Victoria Station or Charing Cross Station, more with transfers), Canterbury (2/hour, 30 minutes, arrives at Canterbury East Station), Rye (hourly, 1 hour, transfer at Ashford International), Hastings (hourly, 1.5 hours, transfer at Ashford International), Brighton (at least hourly, 2.5 hours, transfer at Ashford International or London Bridge Station). Train info: Tel. 0345-748-4950, www.nationalrail.co.uk.

By Bus: National Express (tel. 0871-781-8181, www.nationalexpress.com) goes to London (10/day, generally 3 hours) and Canterbury (6/day, 45 minutes). Stagecoach goes to Rye (hourly, 2 hours) and Hastings (hourly, 3 hours).

Ferries to France: In the mood for a glass of wine and some escargot? A day trip to France is only a short boat ride away (walk-on passengers generally £30 round-trip, car prices vary with demand). Two companies make the journey from Dover: P&O Ferries (1.5 hours to Calais, tel. 0800-130-0030, www.poferries.com), or DFDS Seaways (cars and bikes only, no foot passengers; 2 hours to Dunkirk or 1.5 hours to Calais, tel. 0871-574-7235, www.dfdsseaways.co.uk).

The following sights are in the countryside west of Dover, within an hour or two by train—less by car.

One of the most engaging gardens in southern England, Sissinghurst combines the fascinating story and personalities of its creators with an impeccably designed and maintained manor garden (worth ▲▲▲ for garden aficionados, and ▲▲ for anyone else). Visitors enjoy climbing the surviving castle tower, learning about the dynamic couple who created this place, sniffing around the lovely plantings, and taking a tour of their private home. For an English country estate, it’s loaded with personality and blessedly compact to tour.

Cost and Hours: £13.80, includes tour of South Cottage; garden open daily 11:00-17:30, typically closed Nov-mid-March—but may be open weekends; shorter hours for tower, library, and South Cottage; pay parking, café, plant shop.

Information: Tel. 01580/710-700, www.nationaltrust.org.uk/sissinghurst-castle-garden.

Getting There: Sissinghurst is about 40 miles west of Dover, off the A-262, near Cranbrook. Trains from London connect to Staplehurst, about six miles away (2/hour, just over an hour from Victoria Station, tel. 0345-748-4950, www.nationalrail.co.uk). From Staplehurst, take a taxi directly to the garden (£17 one-way, reserve at tel. 01580/890-003; return taxis can be busy in the afternoon—reserve ahead then as well), or a bus to the village of Sissinghurst, where you can walk along an idyllic footpath about a mile to the garden (path can be muddy; catch bus #5 from Staplehurst, hourly in the afternoon; for more info call 0871-200-2233 or use the journey planner at www.travelinesoutheast.org.uk).

Background: Sissinghurst is the work of writer Vita Sackville-West (1892-1962) and her husband, diplomat-author Harold Nicolson (1886-1968), who began creating their paradise here in 1930. Each was larger than life: Vita was a prizewinning author and poet, and a lover of Virginia Woolf, while Harold served in Parliament and was instrumental in writing the Balfour Declaration (a pivotal document in the creation of Israel). Their relationship was unconventional, particularly for their era: They had an open marriage, and both had same-sex relationships with other people. Vita even eloped to France for several years with another woman. But it worked for them. (Her journals about their relationship were published—after her death—as Portrait of a Marriage, which also became a BBC/PBS miniseries in 1990.) Together, they focused their creative energy on turning this dilapidated castle estate into their idiosyncratic version of the perfect English garden. Today, their descendants still own part of the estate and participate in its management.

Visiting the Gardens: From the parking lot, buy your ticket, then head down the path and into the cone-roofed oast house (which was used for drying hops; these are typical of the Kent region). Here you’ll find introductory exhibits about the development, disintegration, and rebirth of the estate—which was originally built in the 1530s, but had fallen into disrepair.

Enter the grounds through the gatehouse, with more exhibits inside—including a good introductory video, and information about the Mediterranean-style “Delos Garden” that’s currently being built to fulfill a dream of Vita and Harold. Inside the gatehouse’s library wing (to the left, filling the former stables), a portrait of Vita hangs over the fireplace, along with paintings of other family members, some of whom still live on the property.

The castle—formerly a vast and grand affair—has mostly disappeared, but an Elizabethan tower still stands tall. Inside are a few small exhibits and a chance to peek into Vita’s cozy, book-lined writing room. At the top of the tower (78 steps up), you can survey the garden and orchard from above, giving you an excellent orientation to the estate.

In every direction from the tower sprawls a series of interlocking gardens. Shaped entirely by Vita and Harold’s personal whims, and still painstakingly maintained to their specifications, these are laid out in sections, each with a theme. Use your map to explore. Every section feels like a small outdoor room: the Herb Garden, fragrant and colorful; the White Garden, a two-tone masterpiece (all white and green); Harold’s Lime Walk, beyond the cottage, with tidy rows of trees planted with tulips. There’s always something blooming here, but the best show is in June, when the White Garden bursts with fragrant roses.

Tucked behind the tower, the postcard-perfect South Cottage—where Harold and Vita lived (and which is still owned and sometimes used by their descendants)—is typically open to a limited number of visitors on guided tours throughout the afternoon (first tour at 12:00). To secure a space on a guided tour, pick up a free, timed ticket at the cottage kitchen (these are available starting around 11:45—knock). A chatty docent will lead you on a fascinating, quirky, gossipy, intimate tour through the private quarters of this larger-than-life couple. Since the capacity is so small, the garden administration tries not to publicize the South Cottage tours, but they’re worth planning for.

With more time, you can explore beyond the inner gardens, check out the estate’s working farm, or stroll to the nearby lakes. Attendants in the gardens love to suggest how to spend your Sissinghurst time.

If you dream of half-timbered pubs and wisteria-covered stone churches, Rye is the photo op for you. A busy seaport village for hundreds of years, Rye was frozen in time as silt built up and the sea retreated in the 16th and 17th centuries, leaving only a skinny waterway to remind it of better days. While shipbuilding and smuggling were the mainstays of the economy back then, antique shops, pricey restaurants, and expensive B&Bs drive business these days. Curdled in cobbled cuteness, Rye desperately tries to be southeast England’s answer to a huggable Cotswolds village—and it nearly succeeds. But it feels a little artificial and greedy, packed with tourists trying to soak up some charm. Still, it’s worth a stop and a stroll. There’s no official TI, but you’ll find visitor information at the Rye Heritage Centre.

Getting There: Trains connect to Rye from London (hourly, 1.5 hours from St. Pancras International Station, transfer at Ashford International) and Dover (hourly, 1 hour, transfer at Ashford International). Stagecoach bus #102 provides a direct connection to Dover (hourly, 2 hours, tel. 0871-200-2233, www.stagecoachbus.com). If coming by car, Rye is about 35 miles southwest of Dover off the A-259 (the route to Brighton). As you approach town, follow the canal to the old quays. The sea used to come up here, and the parking lot on Strand Quay would have been the wharf. I’d ignore the confusing P signs, which direct you to parking lots away from the town center—instead, navigate the one-way system, follow brown Tour signs, and try to squeeze into the small lot next to the Rye Heritage Centre (by the antique shops) across the street from the canal.

Visiting Rye: Rye’s sights try to make too much of this little town, but a stroll along the cobbles is enjoyable. Here’s an easy loop that will give you a sample of the town.

Start at the Rye Heritage Centre, with a visitor information center, a town audioguide (75 minutes), and an impressive scale model of the town, presented in a 20-minute sound-and-light show (if it’s not running you can peek in at the model for free; Strand Quay/A-259, tel. 01797/226-696, www.ryeheritage.co.uk).

From near the Rye Heritage Centre, cobbled Mermaid Street leads straight up into the medieval heart of Rye. Along this street (on the left), look for the half-timbered, ivy-covered Mermaid Inn, rebuilt in 1420 after the original burned down (today it’s an upscale hotel with plenty of four-poster beds). Step inside and have a peek into Rye’s heyday, or splurge for an expensive lunch. Photos of recent celebrity customers are posted just inside the door.

Continuing up Mermaid Street, jog right up West Street, passing Lamb House—a tourable National Trust property where American novelist Henry James lived and worked (www.nationaltrust.org.uk/lamb-house).

Just beyond, you reach Church Square. The old Church of St. Mary the Virgin has a pleasant interior (described by a free pamphlet), an 84-step tower you can climb for a countryside view, and a red-brick water tower built in 1753 (tel. 01797/224-935).

Beyond the square is a miniature castle called the Ypres Tower, housing the Rye Castle Museum, with a modest collection of items from the town’s past. It’s a fun excuse to twist through some tight stairways and corridors, see artifacts from the town’s history (ships-in-bottles), and learn a bit about medieval crime and punishment. Don’t miss the outdoor section: a prison exercise yard with downward-pointed jagged metal spikes to deter thoughts of escape. At the far end of the yard is a freestanding women’s prison tower built in 1837. Before that, female prisoners—often prostitutes—were simply thrown in with male ones. Towers like this one gave female prisoners a safe space to serve out their sentences (tel. 01797/226-728, www.ryemuseum.co.uk). If you’re visiting on a summer weekend, ask about the museum’s second location—the East Street Museum—which features a 1745 fire engine and more about Rye’s shipbuilding past.

Exiting the Castle Museum, turn right (walking with the church on your left), then turn left at the paved street. You’ll pass the town council hall (a popular wedding venue) on your right, then turn right to walk steeply downhill on shop-lined Lion Street. This takes you to High Street (and a record store filling an old brick grammar school). Turn left and browse your way down High Street, lined with pricey restaurants, twee coffee houses, and tourist-oriented boutiques. As it curves downhill, High Street becomes The Mint, eventually depositing you near the Rye Heritage Centre where we began.

Eating in Rye: The village seems designed to provide passing travelers with an expensive lunch. High Street is lined with a variety of restaurants, for every price range. The Mermaid Inn (described earlier) is historic, though the food is pricey and gets mixed reviews; locals prefer the Standard Inn, along The Mint near the bottom end of High Street.

Near Rye: Compared to sugary-sweet Rye, modest and medieval Winchelsea feels like an antacid. Small, inviting, and just far enough away from the maddening crowd, the town makes a good stop for a picnic lunch. The Little Shop on the square at 9 High Street sells all you need for a quiet meal on the village green. Winchelsea is about three miles southwest of Rye off the A-259, toward Hastings (www.winchelsea.com).

Located an hour southwest of Dover by car, the town of Battle commemorates the Battle of Hastings. In 1066, a Norman (French) nobleman—William, Duke of Normandy—was victorious in the Battle of Hastings and seized control of England, leading to a string of Norman kings and forever changing the course of English history. While the ▲▲ battlefield and adjoining ruined abbey (built soon after the battle by William to atone for all the spilled blood) are worth ▲▲▲ to British-history buffs, anyone can appreciate the dramatic story behind the grassy field. Ignore the tourists and take a journey back in time...these fields would have looked almost the same a thousand years ago. Gaze across the unassuming little valley and imagine thousands of invading troops. Your visit can last from three minutes to three hours, depending on your imagination.

Getting There: If coming by car, the town of Battle is about 7 miles northwest of the town of Hastings. Though not on a major road, it’s well-signed from the busy A-259, whether you’re coming from the east (Dover), the north (London), or the west (Brighton). There’s a parking lot to the right of the abbey complex entrance (£4.50—purchase a token at the ticket desk inside, which you’ll use to exit the parking lot). Battle can be reached by train from London’s Charing Cross Station (hourly, 1.5 hours) or Cannon Street Station (2/hour, 1.5 hours), Hastings (2/hour, 15 minutes), or Dover (2/hour, 2 hours, 1-2 transfers). Follow signs from the train station to the abbey (about a 15-minute walk).

Cost and Hours: £12.30, includes essential audioguide; daily 10:00-18:00, Oct until 17:00, shorter hours in winter and closed certain days (check the website).

Information: Tel. 01424/776-787, www.english-heritage.org.uk/battleabbey.

Eating: The abbey’s visitor center has a $ café serving light meals. And the main street of the town of Battle, right in front of the abbey complex, is lined with other eating options.

Visiting the Abbey and Battlefield: “Battle Abbey” is a sprawling complex that includes some buildings from the abbey monastic complex, the remains of others, a modern visitors center, and what’s believed to be the actual battlefield site.

Enter and buy your ticket inside the towering gatehouse of the abbey complex, peering down the main street of Battle. Be sure to pick up the audioguide. Upstairs in the gatehouse is a (skippable) museum with a few items from the monks’ era.

The audioguide leads you through the three main parts of the exhibit: the visitors center (with an informative movie); a walk through the battlefield itself; and a tour of the various buildings of the partly ruined abbey complex.

The visitors center has a café upstairs, while downstairs are modern, engaging exhibits that set the stage for the battle. The 15-minute film recounts with great drama the story of the battle, with animated scenes from the famous Bayeux Tapestry and live-action reenactments. You’ll also see replicas of weapons used by the fighters that you can brandish—heavy metal.

Just beyond the visitors center is the battlefield site. Here you have two choices with your audioguide: Follow the short tour along a terrace overlooking the battlefield (about 20 minutes) or take the longer version out through the woods and across the fateful field (about 40 minutes, and well worth the extra time if the weather is decent). With sound effects and an engaging commentary that explains both the English and the Norman perspective, the audioguide really injects some life into the site. A few wood-carved figures help stoke your imagination as you walk through the big, empty field.

Regardless of which version of the audioguide tour you follow, you’ll wind up at the remains of the abbey. Built by the victorious William as an act of penance for the gruesome battle he helped cause, this grew into a sprawling Benedictine monastic complex. Today, some of its many buildings are entirely gone, others are ruined but still standing, and others are intact and being used by a local school (and therefore off-limits to visitors). Use the audioguide to chart your own path through the abbey, including some evocative pillared halls and a former dormitory that’s now open to the sky. In the flat area near the top of the complex, find the big, flat stone in the middle of the church-shaped field of pebbles (marking the location of the long-gone Romanesque—or “Norman”—church). This is the Harold Stone, supposedly the place where an arrow pierced the eye of the English king—marking the site of the church’s main altar.

This massive, brooding fortress—in the one-street town of Pevensey—was used in Roman, Anglo-Saxon, medieval, and modern times. (Pevensey is part of the area dubbed “1066 Country,” with ties to the Battle of Hastings.)

Pevensey Castle began as a Roman coastal fortification around AD 290. William the Conqueror made landfall very near here (at Norman’s Bay) on September 28, 1066—just two-and-a-half weeks before the great battle. William and the Normans further fortified the castle, which is also now surrounded by an outer ring from the Middle Ages. The moat around the inner castle was probably flushed by the incoming tidewater (although the present coastline is now farther south). To enter the evocative, half-melted-sugar-cube ruins of the castle, you’ll have to buy a ticket, but there’s not much to see inside—just a small exhibition about its history, including the French Canadian and American troops who were stationed here in World War II. I’d skip the entry fee and just wander the scenic and grassy field around it. You can also step into the entrance terrace to get a sense of the interior.

Cost and Hours: Castle entry-£6.80, includes 45-minute audioguide; daily 10:00-18:00, shorter hours and closed Mon-Fri in winter; tel. 01323/762-604, www.english-heritage.org.uk/pevensey.

Getting There: Pevensey is less than a half-hour drive west of Battle, on the way to Brighton (where the A-259 coastal route and the faster A-27 inland route intersect). Drivers can park in the pay-and-display Castle Market Car Park tucked around behind the castle complex, just off the main road (with a pub and tearoom nearby).