3 Rainbows and Myth

Not unexpectedly, given its apparent immensity, brilliant colours and sudden appearances and disappearances, the rainbow has been assigned mythic or spiritual significance by a bewildering array of national, confessional and cultural groupings worldwide. There is no general agreement about whether certain common rainbow beliefs spread between, or were independently invented by, cultures separated by thousands of miles of desert, jungle or ocean. Rainbow-citing end-of-the-world myths, for example, occur in apparently disconnected traditional cultures in eastern and western Africa; the Baltic states; northern India; southern China; several Pacific islands; Bolivia; Peru; Argentina; Paraguay; the southeastern U.S.; and eastern, western and northern Canada. Many of these can be dismissed as the warped residue of long-forgotten Christian missionary activity that spread the story of Noah and the flood; others cannot. The end-of-the-world rainbow stories shared by the Toba, Mataco and Lengua peoples of the Gran Chaco region of South America, for instance, bear no resemblance to Judaeo-Christian ones, but a very close similarity to some New Guinean and other legends of the southwestern Pacific region.1 While bearing firmly in mind that cross-cultural comparisons of myths ‘can only lead to valid conclusions after intensive study of the belief or custom in each culture-area separately’, the partial evidence assembled by anthropologists over the past century and a half is highly intriguing, as much for the similarities among global rainbow myths as for their many differences.2 Certainly, the rainbow has until relatively recently been an almost universal object of veneration, awe and fear.

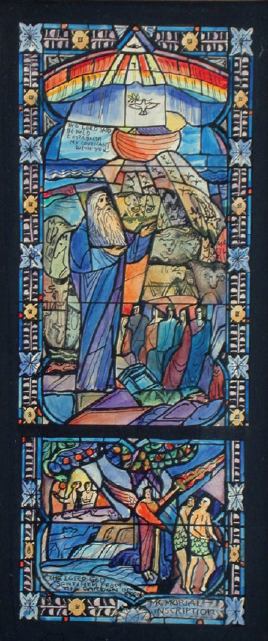

Rainbow of God’s covenant with Noah in a J. & R. Lamb Studios stained-glass-window design from 1857.

The rainbow as bow

The Judaeo-Christian significance of the rainbow is derived from the story of the flood in the Old Testament’s Book of Genesis, after which God sets his bow in the clouds, ‘for a token of a covenant, betweene me and the earth . . . [that] the waters shall no more become a flood to destroy all flesh’.3 Many scholars identify this biblical event with a particular real flood that occurred around 2900 BCE in southern Iraq, the story of which reached the compilers of the Old Testament, working in the sixth to fourth centuries BCE, via earlier Babylonian and Assyrian traditions.4 In medieval Christianity, the rainbow became prevalent in artistic depictions of the Apocalypse, as well as in some of the most popular Corpus Christi mystery plays. With the advent of Protestantism in the early sixteenth century, God’s bow almost immediately became associated with the radical Left – seemingly via a sense that the ‘meek’, broadly identified as the poor, would indeed inherit the Earth in the End Times, pursuant to the promise made by Christ in the Sermon on the Mount.5 However, amid increased scientific appreciation of the causes and forms of the rainbow, trailed only slightly by public acceptance of the latest scientific explanations, most Westerners soon lost their ability to relate to the rainbow as something other than an optical and meteorological phenomenon. One loss in particular was the sense that the rainbow is, or is representative of, a bow: a weapon, used for war or hunting, which had been invented in the upper Palaeolithic era, and arguably brought to a peak of perfection in the fifteenth century, on the eve of its supersession by handheld firearms.

Hans Memling, St John Altarpiece, c. 1479, oil on oak panel. Flames shoot from the rainbow surrounding the figure of God in the right-side panel.

Medieval Europe shared this perception of the rainbow-as-bow with much of the Near East and parts of India. The senior Hindu god Indra, also known as Meghavahana (‘rider of the clouds’), is a weather-controller believed to push up the sky each day to release the personification of the dawn, known as Ushas, from a cave.6 Indra’s main weapons are a bow and vajra, the latter meaning both ‘thunderbolt’ and ‘diamond’ – and for some, ‘the diamond shining like a rainbow’, a fairly clear allusion to prismatic phenomena.7 In the Sanskrit language, the rainbow is called indradhanus, ‘the bow of Indra’, from which also comes the Bashgali word for rainbow, indron.8 Somewhat controversially, it has been asserted that Indra or a theoretical proto-Indra figure spread both eastwards and westwards: becoming Vajrapani Bodhisattva in the Mahayana tradition, the most prevalent form of Buddhism worldwide and the main form of that religion in China; and in the European context, the thunder gods Zeus (Greece), Jupiter (Rome), Thor (Scandinavia and Denmark), Perkunas or Perkuno (Latvia and Lithuania), Ukko or Uka (Finland and Estonia) and Perun (Russia).9 In any case, by the time he reached Japan under the name Agyo, this god was carrying not a bow but a club made of diamond; and his relationship to the rainbow, as distinct from the spectrum, had been broken.10 Ukko, Perkunas and Perun, meanwhile, were all armed with bows, but again without their legends placing any special emphasis on rainbows among a host of weather phenomena that these deities were said to cause, both accidentally and on purpose.11

Another Hindu mythological figure associated with the rainbow-as-bow is the hero-king Rama, seventh of the ten avatars of the god Vishnu in the Vaisnava tradition. One Bengali word for rainbow, rongdhonu, literally means ‘Rama’s bow’, though other words for rainbow in the same language include dēbāẏudha (‘a divine or celestial weapon’) and indrāẏudha (‘the bow of Indra’), as well as simply the name rama by itself.12 Lying geographically between the above-mentioned Indian and European traditions is the pre-Islamic weather-god Quzah, formerly worshipped in the Muzdalifah area of Arabia.13 His bow (qaws Quzah) remains the nearly universal Arabic term for rainbow today, though some recent scholars have questioned this derivation.14 It is also possible, though far from conclusively demonstrated, that the ancient Egyptians associated rainbows with war-bows, at least visually.15 And medieval Englishmen were happy to note that the unvarying position of the rainbow – aimed away from Man, and at God – reflected the state of wary truce between the two that had prevailed since the time of Noah and the ark.16 Though this particular mythic perspective has now vanished, the English language cannot describe a rainbow without reference to it: the ‘bow-ness’ of the bow intractably, implausibly, indestructibly remains.

Though the Judaeo-Christian rainbow was, or was representative of, a powerful weapon, it was a weapon that would never be used; and in the West, the residue of this peculiar and contradictory myth has been that rainbows are now almost inevitably regarded as benign. Likewise, in the minority of world cultures that have regarded the rainbow as a benign object rather than a malign being, it is very often seen as part of the personal kit of an anthropomorphic deity. In this sense, the bow-rainbows of Jehovah, Indra, Ukko, Quzah and the rest can be related not merely to each other, but to the mythical belt-rainbows of Armenia, Albania and Livonia; the necklace-rainbow of Ishtar (the Assyrian, Babylonian and Akkadian goddess of war, sex and fertility); and even, perhaps, the severed penis-rainbow of the hermaphroditic Balinese goddess Uma.17

Ukonsaari island in Finland is sacred to the thunder god Ukko.

The rainbow as cosmic architecture

As will have been noted from the previous section, Indo-European belief in a bow-armed thunder-god appears to have stopped at the border between Finland and Sweden, to the west of which godly thunderbolts were believed to emanate from a war-hammer instead. The global fame of the pagan Scandinavian rainbow bridge known as Bifrost, Bilröst or Asbru has been reinforced by generations of Marvel comic books and, in a twisted form, by the viral popularity of the anonymous poem ‘The Rainbow Bridge’ from before 1993, which promotes the belief that pets and their owners will be reunited in the afterlife. Such is the popularity of this pet-centred bridge that it is increasingly incorporated into mainstream religious practice, for instance, in Japanese Buddhism.18 In actual Norse mythology, the bridge connects the mundane world (Midgard) to the godly realm (Asgard), which will be destroyed during Ragnarok (the ‘twilight of the gods’), after which the world will be drowned in a great flood. Bifrost is explicitly described as a rainbow of three colours in the thirteenth-century Prose Edda by Snorri Sturluson, upon whose work much of our knowledge of earlier Scandinavian mythology crucially depends. Some modern scholars have speculated that the three colours in question may have been red, blue and green; but only the red is actually attested in the original tales.

Lord Rama with bow in a Dussehra Navratri festival poster from India.

Amid the perhaps undue prominence of this medieval Scandinavian tradition in modern culture, it is frequently forgotten that other myths of the rainbow as an inanimate architectural element of the universe are widely dispersed around the globe. Bifrost itself is conceivably a version of the rainbow pathway used by some versions of the Graeco-Roman messenger goddess Iris to move between godly and human realms. Iris, however, was for some ancient authors so closely identified with the rainbow that the ‘bridge’ concept disappeared; her name remains the common word for ‘rainbow’ in Latin, as well as the root of the Spanish and Portuguese words for the phenomenon, and of the English word ‘iridescence’. Some European folk traditions also preserved into modern times an idea that the rainbow was not Iris’ body but her scarf, an idea with which Isaac Newton was familiar, and which presumably inspired the animation of Iris’ cloak in the ‘Pastoral Symphony’ segment of Walt Disney’s Fantasia (1940).

Statue of the goddess Uma, Cambodian, 8th century CE.

Riddles involving the rainbow are extremely common in the folklore of Norway, Sweden, Denmark and northern Germany, though more of these liken the phenomenon to a piece of cloth than to a bridge – making a common origin in the Old Norse tales unlikely. This has led at least one scholar to argue that the rainbow-bridge Bifrost ‘is not of Norwegian origin at all’ but an interpretation of the Graeco-Roman goddess Iris that arrived in Scandinavia via Germany. In any case, riddles about rainbows are considerably rarer in European cultures than ones about ‘other celestial phenomena, such as thunder, sun, moon, and stars’.19

Certain Indonesian, Japanese, Khmer, Siberian Buryat, Hawaiian, Tlingit and Hopi traditions also cite a rainbow bridge connecting the heavens with the Earth and/or the dead with the living.20 The Chumash people of California, meanwhile, have a story that combines elements of rainbow-bridge mythology with the rainbow-snake mythology that is even more common around the Pacific Rim, as well as in Africa (see next section). A small number of other traditions around the world have perceived the rainbow as an architectural element other than a bridge: for example, a rafter (Navajo), or ‘a kind of celestial girder’ in the house of the Queen of Heaven (Zulu).21 More prosaically, a certain type of real bridge in medieval China was called a ‘rainbow’, after its shape.

Friedrich Wilhelm Heine (1845–1921), Battle of the Doomed Gods, illustration from Wilhelm Wagner’s Nordisch-Germanische Götter und Helden (1882).

Rainbows as beings

The Graeco-Roman goddess Iris’ status as a personification of the rainbow is questionable, with some ancient sources citing only her use of the rainbow as a bridge, and others her wearing of the rainbow as a garment. A handsome prince, enchanted in such a way that he can only speak in the presence of a rainbow or spectrum, and who is therefore known as ‘Prince Rainbow’, occurs in one French fairy tale from before 1725.22 But interestingly, other mythic occurrences of rainbows as humanoids – as distinct from their personal possessions or body parts – are rare almost to the point of non-existence. A key exception proving this rule is the Buddhist yogic tradition that certain individuals, such as the Great Guru Padmasambhava, achieved a ‘Rainbow Body’ by transforming the ‘five major organs and systems of the human body . . . [into] five chakras’:

Achievement of the Mahasukha [Rainbow Body] means [to be] transformed into the highest physical form, the rainbow. . . . The highest wisdom is the Light. Sinful persons have no light, just darkness . . . The form and color of the rainbow reflected in the no-cloud blue sky is the physical aspect and the light is the wisdom. The physical flesh body is transformed into the form and color of a Rainbow Body while its light is the wisdom . . . Physically, because he is a rainbow, there is no death.23

Mikalojus Konstantinas Ciurlionis, Thor, 1909, tempera.

Pierre-Narcisse, Baron Guérin (1774–1833), Morpheus and Iris, 1811, oil on canvas.

It is worth noting in this context that the Buddha himself, or rather his aura, is associated with five colours: ‘royal blue, golden yellow, dark red, white and magenta orange’.24 Pre-Newtonian and non-European rainbows with as many as five colours (as in Chinese tradition) are rare, however, and mythic rainbows of six or more colours are as yet unrecorded.25 Nevertheless, conceptions of the colours of the rainbow and their number are nearly as variable as culture itself. The ancient Greeks and others saw, or chose to see, a monochrome bow of red or purple. If there is a worldwide norm for mythic rainbows, it is probably for a three-coloured bow in which one of the colours is red, though two- and four-colour versions are also fairly common. For West African Yoruba people of the transatlantic diaspora, ‘the image of the rainbow serpent Òṣùmàrè signifies the continuity of life and the blessings of the ancestors’, and its four colours are ranked in terms of seniority: the oldest and therefore most important is white, followed by red, blue and yellow.26 Those Yoruba who accept that black is a colour conceive of it as an extremely intense form of red or blue, and therefore it is ranked second or third after white.27

|

With regard to the ‘continuity of life’ more specifically, Òṣùmàrè – who is either a seasonal gender-shifter or hermaphrodite, according to different Yoruba sub-groups – is associated with human procreation and the umbilical cord.28 As rainbow-serpents of the world go, however, s/he is perhaps exceptionally benign, appearing in insurance advertising in Benin, while the popular Nigerian music group Osumare translate their name merely as ‘rainbow’ – seemingly without any intent to go beyond the general sense of positivity and inclusiveness that this word and image tend nowadays to arouse among Europeans and North Americans.29 This may have to do with the fact that, in the twenty-first century, worship of Òṣùmàrè is ‘more common in the Americas than it is in West Africa’.30 The same deity is known as Dan Ayido Houedo among the Fon-speaking peoples of Benin and southwestern Nigeria.31 Like his non-rainbow-affiliated python-god predecessor Dangbe, whom he absorbed during the eighteenth-century military conquest of the Kingdom of Savi by the Kingdom of Dahomey, Dan Ayido Houedo controls movement, both between the earthly plane and the afterlife, and between different states of wealth and social status.32 Other groups in both East and West Africa harbour similar beliefs, with the Hausas’ Gajjimare – another gender-shifter – being perhaps the most similar.33 In the highlands of central Haiti, the sex-shifting African deity is normalized as a couple: Ayida Wedo is the female rainbow, and Damballah-Wedo her serpent-husband.34 For the Mbuti of the Democratic Republic of Congo, meanwhile, the rainbow is unambiguously a ‘terror-inspiring, man-murdering snake-monster that devours human beings and brings about catastrophes’.35

|

Among the Feranmin people of New Guinea, the rainbow-serpent Magalim is said to live in mountain pools; when roused, he causes earthquakes, rain and thunder, and rises from the waters to swallow the person who awakened him. Though the Earth’s surface would collapse without him, he is the enemy of mankind (and especially women) and a principal cause of both madness and malaria. He is similar in shape to a python, but ‘enormous’, and all serpents, eels and rainbows are related to him. His scales, if captured, ‘can give a warrior the shimmering quality of the rainbow so he cannot be targeted by arrows’. This set of beliefs, far from being unique to the Feranmin, is part of ‘an old formulation which has circulated through the region for some time and now finds partial expression in various groups’, not merely in other parts of New Guinea but throughout Australia, where it has been described as ‘characteristic of Australian [Aboriginal] culture as a whole’.36 One of the universal characteristics cited is the association of the creature with naturally occurring prismatic or iridescent materials such as quartz crystal and mother-of-pearl. The disease element (as distinct from violent assault) is less clear-cut, though Aboriginal groups around Perth attribute to the rainbow-serpent ‘all sores and wounds for which they cannot otherwise account’.37

Certain rainbow-snakes of Indonesia, ravishers of women and bringers of insanity, guard stocks of gold under the earth, and can cause this gold to ‘rise up in the form of a rainbow’ from their mouths.38 A similar mythos, including the pot of gold, was particularly widespread in northern British Malaya, where various peoples used at least eight different words for the rainbow, all of which also meant ‘serpent’. As elsewhere in the region, these creatures were unlucky and caused fevers. Moreover, by the early 1960s, such beliefs had spread from the indigenous to the non-indigenous population.39 In the Philippines, the Mangyan people of the island of Mindoro and the Tagbanua people of Palawan specifically associate rain during rainbow-snake appearances with the danger of disease, in a more clear and direct manner than, say, the Feranmin do.40

Uniquely, perhaps, the rainbow-serpent Wanamangura of the Talainji (Western Australia) is associated with moonbows as well as rainbows.41 For the Lardil people of Mornington Island, the serpent is part of a cautionary tale about hospitality and the mistreatment of outsiders: because he refused succour to a foreign woman, Rainbow Serpent not only caused her death, but ‘Rainbow Serpent’s own Country ceased to exist after his fit of selfishness’.42 Further exemplary tales of the creature – from Australia, Java, Bali and throughout the southwestern Pacific, as well as parts of China – are almost endless, while in India, ‘whatever their other sectarian differences . . . Buddhists, Hindus, and Muslims share a common set of stories that joins earth mounds, serpents, rainbows, and treasure.’43 Within the very broad region covered by the present paragraph, belief that the rainbow-serpent is essentially benign appears limited to Queensland.44 That being said, even within Queensland, the Kabi regard the rainbow-serpent as ‘tricky and malignant’, a slaughterer of men and shatterer of mountains, who tends to be helpful only to those people who already possess magical powers of their own.45

The rainbow-serpent myths of the Americas appear to occupy a middle position between, on the one hand, those of Africa (with a few key exceptions – for example, Mbuti, Zulu, Masai and Murle), in which rainbow-serpents tend to be benign; and on the other, those of the peoples of the southwestern Pacific Ocean and Southeast Asia, who overwhelmingly view such deities as both vicious and noxious.46 Among South American groups, the Cumaná of Brazil and Guayakí of Paraguay seem to view their rainbow-serpents as especially dangerous, and the Panare of southern Venezuela use the same word to mean rainbow and ‘were-anaconda’.47 The Zuni mythology of the plumed water serpent, while it does not cite the rainbow specifically, is strikingly similar to various rainbow-serpent myths from the opposite side of the Pacific, previously referred to; and the Yaqui have stories of water-dwelling snakes with great spiritual power and ‘rainbows on their foreheads’.48 Many Amerindian groups including the Botocudo from eastern Brazil see rainbow-snakes as relatively unthreatening bringers of rain; but it would be simplistic to assume that a deity is benign simply because s/he is described as a ‘bringer of rain’, since such a deity if displeased might become rain-denying or even a bringer of drought.49 Moreover, the desirability of rain may vary widely from place to place, from season to season, and from year to year, even within a particular belief-group.50

Replica of an Australian Aboriginal rock painting of Namaroto spirits and the rainbow-serpent Burlung, in the Anthropos Museum, Brno.

Rainbow in the mountains of Lachung, Sikkim, May 1971.

The passage of rainbow-serpent belief from West Africa to the slaveholding countries of the Western Hemisphere is readily explicable in historical terms. Other such trans-oceanic leaps are less so. One of the very few previous surveys of global rainbow mythologies managed to give an impression that the rainbow-as-malign-snake mythos had ‘jumped’ the South Pacific, somehow stretching from Australasia, Southeast Asia and Melanesia to Latin America without passing through northeastern Asia or the northern Americas en route – an apparent denial (albeit offhand) of the Bering Strait Land Bridge Theory of the peopling of the Americas.51 A detailed analysis of roughly a thousand myths from the Bering Strait to Tierra del Fuego provides a different view entirely: in both North and South America, skunks and opossums are mythic opposites. North American myths associate the skunk with the burnt (and the rainbow) and the opossum with the rotten. Both have the power to resuscitate the dead. In South America, on the other hand, it is the opossum that is associated with the rainbow (to the point that in Guiana they share one name, yawáre), and both are credited with lethal power.52

John Loewenstein concluded that

Myths of a giant rainbow-serpent . . . must be intimately connected with the occurrence and geographic distribution of a particular family of snakes, the Boidae . . . [This association] may indeed have its origin in the brilliant colours and iridescent glow of most of these imposing reptiles, in their aquatic habits, their capacity to climb trees, and, last not least, in their habit to hibernate and reappear after the first seasonal rains.53

However, he goes on to admit that ‘zoological evidence alone cannot explain’ the mythos’s ‘almost world-wide distribution’, and instead endorsed the idea that the rainbow-serpent myth could have had a ‘very early prehistoric’ origin, and been distributed worldwide with ‘the first dispersal of mankind’ out of Africa.54

University of Hawaii linguist Robert Blust specifically assigns a unitary, pan-human rainbow-serpent mythos to the Pleistocene epoch, and argues ‘that dragons are the end point of a conceptual development which began with rainbows’ and ‘arose through processes of reasoning which do not differ essentially from those underlying modern scientific explanations.’55 Blust asked,

Why are dragons so often associated with waterfalls, pools, and caves? Why are they widely regarded as controllers of rain? . . . Why do they live in terrestrial water sources and yet take flight at the time of the rains? Why are they attacked by thunder or lightning? Why do they breathe fire? Why do they often guard a treasure, in particular a hoard of gold?56

Blust’s arguments point up a major philosophical split within the study of myth, and in particular the study of geographically dispersed but very similar myths such as Rainbow-Snake and Rainbow-Bridge. Scholars – largely according to their own taste – have tended to ascribe the wide distribution of such stories to one of three processes: inter-cultural communication; simultaneous invention; or the fragmentation of a single myth that was once common to all people. Blust argues vigorously against the first possibility, on the grounds that ‘global diffusion implies contacts for which we need some type of independent evidence’, and in favour of a combination of the second and third elements, wherein the fragmentation of a single, universal mythic figure of perhaps 100,000 years ago – Rainbow-Serpent – led to the independent development of dozens of different dragon mythologies.57 My own research, in contrast, indicates that the pre-modern diffusion of ideas and stories was constant, ubiquitous and mostly unremarked in official sources.58 I would therefore suggest that the notion needing to be proved in the Rainbow-Serpent and Rainbow-Bridge scenarios is not the existence of long-range cultural diffusion, but rather the existence of long-term cultural isolation or impermeability. The rainbow-snake mythos was not entirely unknown even in Europe, with a variant being recorded in Estonia, while the Old English language had similar terms for the rainbow, rén-boga, and a coiled snake, hring-boga.59 Even the giant Midgard Serpent of pre-Christian Scandinavia, famously defeated by the thunder-god Thor, can be argued to differ from rainbow-serpents only in degree, on the grounds that disparate world myths make rainbow-serpents the enemies or opposites of thunder or lightning.60 As such, it is intriguing to compare the Graeco-Roman messenger-goddess Iris, who is frequently identified with or as the rainbow, and the Norse entities that seem to fulfil her function at various times and in various ways: Yggdrasil the world-tree, Ratatoskr the sarcastic messenger-squirrel and, of course, Bifrost itself.61

|

Rainbow Gathering in Bosnia, 2007.

It would be a mistake to conclude this section without referring to the Rainbow Family of Living Light, a modern nomadic tribe founded in or by 1972. Originally operating within the United States, it had spread to Europe by 1983 and boasted 100,000 members worldwide in 1999.62 Regular ‘Rainbow Gatherings’, whose attendees might or might not identify themselves individually as ‘Rainbows’, consist of

a collection of camps including ‘Jesus camps,’ Krishnas, ‘faeries,’ camps of meat eaters and of vegetarians, substance-free camps, and camps of heavy drinkers. Yet the Gatherings as a whole are marked by a common commitment to radical equality and respect for diversity, personal freedom, and the environment.63

On the negative side, Rainbow life has been marked by ‘perennial conflicts . . . with the U.S. Forest Service and the mass media’ as well as an arguably racist ‘appropriation and invention of American Indian traditions and iconography’ (in Europe as well as North America), amid ‘little willingness to deal respectfully with actual Indian communities’.64

Rainbows, luck and fear

The rainbow, perhaps due to the fact that it can still be seen everywhere, has escaped the fate of most European mythic figures in modern times – namely, to be ‘excluded from everyday life and relegated to the vague and frightening zone where everything that was an object of religious belief was assumed to belong’.65 Notions of the rainbow as unlucky prevailed well into the twentieth century in many parts of Europe, including England and Russia, especially among children.66 Nor would it always be good luck to find the fabled pot of gold allegedly placed at the rainbow’s end by an Irish leprechaun – a subtype of fairy that is itself ‘a symbol . . . of luck’ but which, like most other fairies, has a number of sinister characteristics.67 Pointing at a rainbow was considered ‘foolhardy’ in Hungary, and unlucky or dangerous in Hawaii, Indonesia, China, Central America and Gabon, leading a recent scholarly work to characterize this act as a ‘near-universal taboo’.68 And in the relatively recent folklore of Albania, Bohemia, France, Hungary and Serbia, rainbows were believed to cause unwelcome, or at any rate unexpected, sex changes in humans.69

Rainbow and leprechaun parade float in France, 2015.

The evidence for pre- or non-Christian survivals, within Europe, of a menacing folkloric rainbow could probably be multiplied. In any case, the bow of God’s covenant is perhaps menacing enough in its implications. For instance, the covenant does not prohibit God from destroying life on Earth via plague, earthquake or indeed anything other than flood, as the title of James Baldwin’s book The Fire Next Time (1963) pointedly reminds us. It was claimed in the early Middle Ages that no rainbow would be seen in the forty years immediately preceding the Apocalypse, and also that the predominately red colour of the bow indicated that the world would be ended by fire.70 As such, it is worth wondering whether the two dominant modes of engagement with the rainbow today – as a harmless and (mostly) explicable scientific phenomenon, and as cute, cuddly kitsch – both equally serve to paper over the awe and fear that rainbows have inspired throughout human history and in every part of the world.