7

Social Work and Globalization

7.1 Introduction

This book has so far focused on social policy in the UK and the implications of recent policy developments in England for social work, but national social policy is increasingly shaped by institutions and events beyond the nation state. This has occurred partly as a consequence of economic globalization and its social and cultural effects, and partly because of the development of a whole variety of supranational institutions, from regional bodies such as the EU to global ones, such as the UN or the IMF, which affect policies in individual nations. This chapter looks at globalization as a phenomenon and its implications for social policy and social work in Britain, and for social work as a global profession.

7.2 What is globalization?

Globalization is a contested concept but the term is used to refer broadly to the effects of the interaction of developments in a number of different spheres: technological, cultural and social, political and economic (Lorenz 2006). The interaction of these developments has resulted in

a dense, extensive network of interconnections and interdependencies that routinely transcends national borders … These interconnections are expressed in ways that appear to ‘bring together’ geographically distant localities around the world, and events happening in one part of the world are able to quickly reach and produce effects in other parts of it. It is this enmeshment which gives rise to consciousness of the world as a shared place. (Yeates 2012: 194, emphasis added)

This enmeshment has three dimensions: (i) events and activities occur over a very wide geographical area (extensity); (ii) the degree and regularity of interconnectedness have increased (intensity); and (iii) these global interactions and processes take place far more quickly than in the past (velocity) (Yeates 2012: 195).

For example, the development of the internet and of social media has made it possible for individuals around the world (extensity) to communicate with each other frequently and copiously (intensity) and almost instantly (velocity). This in turn has had important social and political consequences. The results are evident in new methods of organizing social movements, as recent pro-democracy social protests in Hong Kong (2014) and Egypt (2012) showed. It has become possible to mobilize large numbers of people very quickly over a wide geographical area, in a way that would not previously have been possible. Developments in communications technologies have had other very important effects at a whole variety of levels, from enabling families and friends to stay in touch across continents to facilitating business transactions around the world at all times of the day and night. These technologies have also brought immediate and vivid access to events around the world through news media, and have made people in different countries much more aware of events such as natural disasters, wars, disease or famine in distant parts of the world. Another consequence of advances in communication technologies has been to create much greater possibilities for exposure to other cultures, and this, combined with the dominance of a small number of global corporations such as Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, Nike, SKY and Apple, has resulted in a degree of cultural convergence across the world.

In the economic sphere, globalization refers to the practices of large corporations which organize their production across the globe, siting factories in countries with low labour costs and relatively lower levels of labour protection, and producing goods to be sold throughout the world. If conditions change, these corporations can move production to another part of the globe, with major economic and social implications for the countries that they move away from or into. Lorenz (2006) argues that globalization has produced transnational as opposed to multinational corporations, which constitute an economic network that has freed itself from a link to a distinct geographical location as a ‘base’, in order to achieve maximum flexibility of the production process. The power of transnational corporations to affect the economies of the countries where they operate gives the interests of big business considerable influence over economic and social policies in those countries. This has contributed to the ideological dominance of neoliberalism around the world, with the priority this gives to the free operation of the market and minimal state interference. It has also reduced the power of individual nation states to introduce social policies which might increase labour costs, or reduce corporate profits. Corporations are able to locate themselves in the country whose tax regime is most advantageous to them, which may not be the place where their profits are made. Such tax avoidance reduces state revenue in those countries which have less ‘corporation-friendly’ tax policies, and therefore, amongst other things, the resources available to fund welfare services. Recent examples include Amazon, which has made its European base in Luxembourg to minimize the tax paid on its profits, despite the revenue from its business in Luxembourg representing a tiny fraction of its total sales in Europe (Guardian, 8 October 2014). Similarly, Apple channelled its European business through Dublin, to take advantage of lower corporation tax in the Republic of Ireland (BBC News 29 September 2014).

Global financial markets, using the power of information and communications technologies, are able to shift enormous amounts of capital around the world within moments, with dramatic effects on the economies of individual countries, as was apparent in the 2008 financial crash, and more recently in Russia, with the devaluation of the rouble in December 2014. These economic effects have major implications for the living conditions and social policies of individual nations, and are the results of actions by institutions which can operate beyond the control of national governments.

The power and autonomy of nation states has also been challenged by the growth in the number of supranational institutions whose treaties, regulations, directives and rulings impinge on what national governments do. These institutions may also be influenced by powerful transnational businesses. At a regional level, nation states have grouped together, often primarily for economic reasons, but with consequences for other aspects of national policy for the members of the group. In Europe, the EU promotes the free internal movement of capital and labour, but has also introduced a range of social policies that are binding on its members, as one means of creating a ‘level playing field’ amongst them. Thus, gender equality legislation is a requirement of EU membership, including rights to maternity, paternity and parental leave, and equality within national social security systems. New supranational institutions, such as the European Commission or the European Court of Justice, have been created by the EU to develop policies and enforce legislation across its member states. Similar groupings exist around the world – for example, in Africa, the Southern African Development Community; in South America, the Mercado Comun del Sur; and in South East Asia, the Association of South East Asian Nations.

At a global level, inter-governmental organizations, such as the IMF, are able to exercise considerable power over the policies of individual states. For example, when Greece had to borrow from the IMF in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis to avoid defaulting on its loans, the IMF made it a condition that public expenditure was drastically cut and state assets sold, with impoverishing effects on a significant proportion of the population. Similarly, when the UK government had to borrow from the IMF in the 1970s, the loan was conditional on cutting public expenditure and this heralded the end of Keynesian policies which aimed to minimize unemployment (see chapter 1). Other global inter-governmental organizations include the World Bank, the UN, the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The policies of these organizations exercise considerable influence in a variety of ways over the countries that are members.

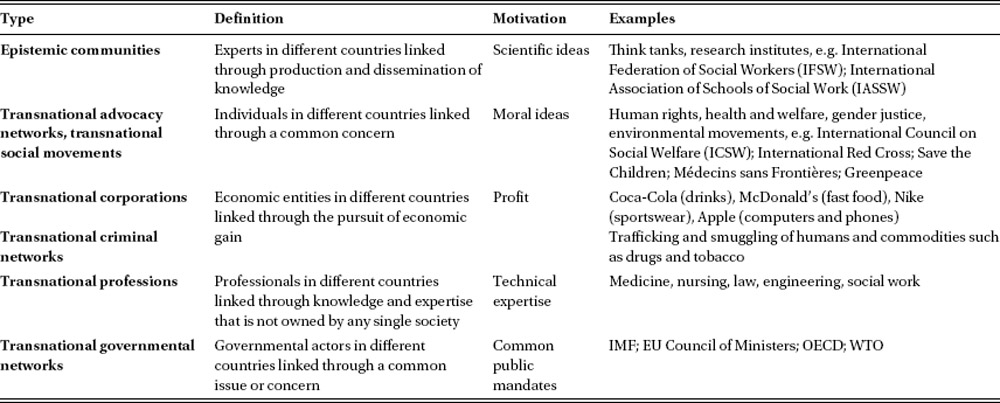

The expansion in the number of inter-governmental organizations is matched by a growth in international non-governmental organizations representing transnational social movements or advocacy networks, which lobby on social policy issues and are involved in the delivery of social policy (Yeates 2012). Yeates provides a helpful summary of the different kinds of entities to which globalization has given rise and their motivations (see table 7.1).

As a consequence of globalization, the power of nation states has been ‘hollowed out’, with ‘state powers and capacities … moved upwards, downwards and sideways’ (Jessop 2000, cited in Lorenz 2006). International interdependence has increased because ‘events and decisions in one country or region can have far-reaching effects on the populations of apparently or formally unrelated countries’ (Lyons 2006: 367). This means that to understand social policy in a given nation it is necessary to look beyond national borders and consider the ways in which these different entities affect national policies and their implementation.

Social work and globalization

While it is clear that the developments outlined above are important for understanding the pressures and constraints on national social policy, how far are they relevant to social work? Opinions on this are divided. Webb argues that ‘social work has at best a minimal role to play within any new global order, should such an order exist’ (2003: 191) and ‘any notion of global or trans-national social work is little more than a vanity’ (2003: 202). However, for others, while they agree that social work is mainly concerned with local practice, the fact that many of the social problems that they deal with have their origins, directly or indirectly, in global or regional events means that it is important to have an understanding of this and to develop responses that address them regionally or globally. Furthermore, since welfare policy is subject to regional, international and global influence, social workers need to understand this and the implications for practice developments and ‘must now think in terms of trans-national as well as trans-cultural social work’ (Lyons 2006: 378).

Table 7.1 Typology of transnational entities

Source: adapted from Yeates 2014: 4. Reproduced by permission of Polity Press.

The influence of neoliberalism through global policy forums such as the OECD, and the more local effects of EU membership and the closer exchange of policy ideas which this has brought, has resulted in some degree of policy convergence within Europe and across OECD members. At the same time, local conditions and cultural practices continue to play a significant role in shaping the way in which policy is implemented, and local ‘bottom up’ responses are important in modifying global social policies, a process which Harris and Chou (2001), in their study of community care policy in the UK and Taiwan, call ‘glocalization’. Across Europe, for example, national policy is converging on ‘cash-for-care’ systems, with increasing marketization of care services and, arguably, a reduction in social solidarity and collective responses to care needs. However, the ways in which this policy is implemented in different countries differ according to the nature of the welfare regime (see chapters 2 and 6), with important implications for the character of the market in care that has been introduced (see, for example, Winkelmann et al. 2014). This points to the importance of social workers having an awareness of global pressures, combined with an understanding of their own local and national institutions.

Social work has always been an international profession, although international issues have rarely assumed much significance on UK curricula or programmes (Lyons 2006; Powell and Robison 2007). Early social work pioneers worked and lived across national borders and many were politically active. A concern with international social justice issues such as poverty, famine, women’s rights and world peace brought these pioneers together and ‘through scholarship and advocacy, organizational leadership and international travel and direct cultural borrowing [they] contributed to [international] diffusion of social work knowledge’ (Hegar 2008: 722). Globalization makes such international cooperation and the exchange of ideas and experience across national boundaries even more important for contemporary social work.

The following sections look in further detail at how globalization gives rise to new kinds of social problems for social work in Britain, at the role of supranational governmental and non-governmental bodies in creating and responding to social problems, and finally at internationalism within social work as a profession.

7.3 Social problems arising from economic globalization

Migration

One of the consequences of economic globalization has been an increase in migration around the world. Extreme poverty and conflict in the Global South have resulted in flows of economic migrants to Europe, and a rise in the numbers of refugees and asylum seekers. Forced migration from non-Western countries is increasingly becoming a major socio-political issue for many Western countries that have tried to stop the inflow of migrants searching for better living conditions (Jönsson 2014). Attempts to restrict immigration through increasingly strict border controls have in turn created the conditions for a global criminal business in people trafficking, with migrants subjected to forced labour in a variety of industries and forced into criminal activities. Women and girls are particularly vulnerable to sexual exploitation and trafficking (US Department of State 2014). Membership of the EU has also resulted in significant population movement between EU member states. All of these developments have important consequences for social work.

Although there is a long history of immigration to the UK, including drawing on the population of British colonies to meet labour shortages in the UK in the 1950s and 1960s, globalization has resulted in immigration from a wider range of countries, over a much shorter period of time, resulting in much greater cultural and ethnic diversity. According to the 2011 Census, 13 per cent of UK residents (7.5 million people) were born outside the UK, an increase of over 3 million people since the previous census in 2001. In London the proportion of the population born outside the UK rose to 37 per cent, making it the most diverse city in the UK, with only 44 per cent of people in London in 2011 describing themselves as ‘White British’ (BBC News 11 December 2012).

As Williams and Graham point out (2014), migration is driven not only by economic motivation but also, increasingly, by transnational networks involving family and community ties. Contemporary migration patterns are more likely than in the past to involve stretching families across space, creating ‘global chains of care’ (Hochschild, cited in Garrett 2006: 323). Another characteristic of more recent migration patterns, associated with globalization, is migration as a temporary rather than a permanent phenomenon. This applies particularly to younger workers migrating within the EU, and to the higher education sector, where students may come for a limited period of study and then return to their home country or move to a third country. These different patterns of migration amongst different groups and for different purposes point to the importance of resisting the homogenization of migrants to the negative stereotype commonly found in the media, where migrants are portrayed as scroungers or a drain on welfare systems, overlooking their diversity and the positive contributions which they make.

Immigrants from some ethnic minorities tend to be over-represented among those who are poor – partly because of discrimination – and to suffer associated problems of poor health and disability, and are therefore more likely to come into contact with social services. Anti-immigration sentiment, whipped up by media-scaremongering about immigrants ‘swamping’ the UK and representing a drain on the welfare state, has resulted in new rules that seek to exclude various categories of migrants from access to welfare services. Consequently, the policing of eligibility has increasingly become entwined with managing national borders as refugees, migrants and aliens become identified with ‘benefit tourism’ and taking advantage of the welfare system (Garrett 2006: 322). This hostile discourse around immigration makes immigrants particularly vulnerable to discrimination and abuse.

Williams and Graham (2014) argue that policies of multiculturalism which prevailed in the 1980s have been replaced by a focus on integration, in which cultural and language differences are seen as problematic and underpin a deficit model adopted in working with immigrants (see also chapter 4). They point to the importance of acknowledging processes of intergenerational change, with second- and third-generation immigrants differing very significantly from their parents and grandparents. This underlines the importance of not constructing all migrants and their descendants as ‘other’, and so failing to acknowledge the ways in which communities adapt and change over time.

Migration raises important issues for social workers in relation to kinship care, an example of the global chains of care referred to above. Kinship care refers to the care of children, whose immediate family is unable to care for them, by members of the extended family or, in some cases, friends within the same community. The 1989 Children Act proposed this as the preferred option, and in the context of a shortage of foster carers and the desire to find culturally appropriate care it has received more attention recently (Lyons 2006). For migrant families, this may mean that children are left in, or sent from the UK to, another country to be cared for by members of the extended family. This in turn may involve social workers in working internationally to ensure children are safe, requiring that social workers familiarize themselves with aspects of the welfare system and immigration legislation in the host country. Lyons gives the example of children, whose mother was unable to care for them in London, being sent to live with their aunt and her husband in Paris. Social workers had to travel to Paris to visit the family and discuss the arrangements with them through an interpreter. Conversely, children may be sent to the UK to be cared for by members of the extended family if their parents are unable to care for them or because they believe that this will be in the child’s best interests. The case of Victoria Climbié, sent from Ivory Coast to London to live with her great-aunt (see chapter 4), illustrates the difficulties that social workers and other professionals faced in disentangling respect for cultural difference from the obligation to ensure a child’s safety and well-being.

‘Illegal’ migrants

Policies in the UK and elsewhere in Europe to restrict immigration have contributed to the growth in international criminal gangs trafficking those who are unable to gain legitimate entry. Once in the UK, their undocumented status makes these migrants vulnerable to continuing exploitation by those who trafficked them and by unscrupulous employers. Women are particularly vulnerable to labour market exploitation, human trafficking and sexual violence. A Swedish study examining social workers’ interactions with undocumented workers found that social workers tended to see these migrants either as ‘victims’ in need of education and development, or as ‘illegal’ and therefore not entitled to any form of support. These perceptions were gendered, with women and children more likely to be seen as victims, while men were more often seen as responsible for their situation and the difficult position in which this placed them and their families. However, social workers found themselves in a dilemma in responding to ‘illegal’ migrants, between their obligations to someone in need, and following national law and rules (Jönsson 2014). The problem in Sweden has been ‘offloaded’ onto the NGOs which have taken principal responsibility for responding to the needs of undocumented migrants. Social workers’ responses to the dilemmas which these migrants posed fell into three categories: conformists framed the problem in individual terms, as one of poor individual choices, which they bore no responsibility to solve; those who adopted a critical position saw illegal migration as a product of neoliberal globalization. They were committed to resisting pressures for a managerialist approach to social work, and saw their role as committing them to fighting for social justice. They used their discretion to find ways round the rules of social work practice in the interests of those they were working with. The third group, the legalistic improvers, looked for ways in which they could exploit legal loopholes to secure provision for undocumented migrants, for instance by using the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Similar dilemmas exist in the UK, where social workers may face conflict between their safeguarding duties and immigration policy. They may find themselves simultaneously acting as ‘agents of control’ and ‘gatekeepers to services’ while struggling to protect vulnerable adults and children (Ottosdottir and Evans 2014). This in turn makes it hard to retain the principles of social justice and care central to social work ethics. The annual US Department of State country-by-country report on trafficking and slavery identifies some of the difficulties that social workers may face in negotiating between law enforcement and meeting needs. The report’s recommendations for the UK include:

- Balancing law enforcement with a victim-centred response to protect trafficking victims

- Ensuring that a greater number of victims of trafficking are identified and provided access to necessary services regardless of immigration status

- Providing victims with access to services before they have to engage with immigration and police officers

- Ensuring child victims’ needs are assessed and met

- Ensuring child age assessments are completed in safe and suitable settings and children are not awaiting care in detention facilities. (2014: 394)

Refugees and asylum seekers

Asylum seekers are a distinct category of migrants, who have been forced to leave their country of origin because of the threat to their safety from war or political or religious persecution or natural disasters, and who are seeking permission to remain in the country where they have sought refuge. Refugees are asylum seekers who have been granted such ‘leave to remain’. Until this legal status is granted, asylum seekers in the UK have very limited entitlements to financial support and to social care, and have to live with the fear that their asylum claim will be turned down and they will be deported. Asylum seekers are not allowed to take up paid employment and the level of welfare benefits they receive is substantially below the level of Income Support. They are not entitled to any additional benefits for disability. A high proportion of child asylum seekers have suffered trauma of some kind and there are high levels of mental and physical ill health within this population (Children’s Society 2012).

Children may arrive as unaccompanied minors, who have experienced trauma and loss, but whose need for care may be subordinated to the demands of the immigration service to establish their age in order to determine their legal status and their rights. Where the UK Border Agency does not accept a young person’s claim to be a minor, they are treated as an adult until their age can be established. There were 1,400 age disputes in 2008, and procedures for assessing age are a matter of concern to the professionals involved. In 2008, approximately 6 per cent of children in public care were unaccompanied asylum seekers (Wade 2011b). Assessment of unaccompanied children and young people presents considerable challenges to social workers, who may be dealing with children who have been traumatized and may be wary about revealing information about themselves because of uncertainty about how it will be used. Wade’s study found that social workers were sympathetic towards the accounts given by the young people they worked with, but fewer than half the assessments were rated adequate or better by the researchers. The initial assessment tended to focus only on the most basic facts and Wade therefore argued that young people’s accounts of their experiences needed to be returned to throughout their placement, in order to provide them with opportunities to re-tell their story.

Where social workers were able to find placements for the young people which provided the opportunity to build new attachments, resume education and construct networks of social support, this had protective effects in terms of the mental health and resilience of the young people. However, both social workers and the young people had to cope with a high degree of uncertainty about the future. The majority of unaccompanied minors are only given temporary leave to remain in the UK and are expected to return to their country of origin when they reach adulthood. Most young people would prefer to stay in the UK. This means that social workers need to be prepared to work with young people to help them face this difficult future and to plan for the uncertainties of potentially returning to their country of origin, with which they may no longer be familiar and where they may have few family or social connections.

Williams and Graham (2014) argue that the effectiveness of current social work approaches to working with all categories of migrants is limited by four inter-related processes:

- decontextualization: social workers’ failure to understand the situation of the migrant in the contexts both of global neoliberal economic doctrine and of the co-ordinated attempts to exclude migrants and asylum seekers;

- disaggregation: individualization and separation of needs, resulting in a lack of understanding of the complexities and intersections of migrants’ situation;

- culturalization: a focus on cultural or language issues as problematic – this constitutes migrants as ‘other’ and fails to see them as rights bearing;

- the replacement of multiculturalism by policies of integration. This leads to social workers adopting ambivalent assimilationalism. The ambivalence resides in social work’s ethical commitment to social justice, care, user involvement, partnership and empowerment. Assimilation threatens to devalue cultural difference and impose a mythical unitary ‘British culture’ (see also chapter 4).

Contributions of migrants to social care

As we have seen (chapter 6), there is growing demand for social care because of an ageing population, high levels of female employment and greater survival of people with long-term ill health and disabilities. The social care market is increasingly dependent on workers recruited from abroad to provide personal care in both residential settings and individuals’ homes. Jobs in the care sector are generally female dominated, poorly paid, involve demanding work and have low status, and this means that the indigenous population may be reluctant to take them. Yeates (2009) argues that there is a new international division of reproductive labour – of which social care work is a part, and which governments condone and even encourage – that involves the export of female labour. Women migrants’ work as care assistants in the UK not only helps meet domestic demand, but also helps families and communities in their country of origin through the remittances which they send back, as part of a ‘global care chain’, involving women from the Global South working in the Global North to support children left in the care of female relatives (Williams 2010).

While stricter immigration legislation has recently made it very much more difficult for new migrants to enter the UK from outside the EU to undertake this kind of low-paid work, migration within the EU from Central and Eastern Europe remains an important source of labour for care work (Williams 2010; Hussein et al. 2011). In Hussein et al.’s study (2011), employers and Human Resources (HR) managers characterized migrants as hard-working, honest and reliable, often in contrast to UK workers. Migrants were also felt to have a more respectful attitude to older people and to care genuinely about those they worked with. Many migrants were better qualified than care workers recruited locally, and in some cases saw care work as a good point of entry that would eventually lead to better-paid work more consistent with their level of qualification.

Williams (2010) argues that a new transnational political economy of care has come into existence. This has four dimensions: the transnational movement of care labour; the transnational dynamics of care commitments, involving care at a distance, substitute care or a lack of care because of migration; the transnational movement of care capital, referring to the rapid growth of commodified care as big business; and finally the transnational influence of care discourses and policies manifest, for example, in the widespread adoption by European welfare states of cash payments to enable individuals to purchase their own care (see chapter 6).

Transnational care capital

The marketization of social care services, discussed in chapter 5, has opened up new commercial opportunities for private companies selling care services. In the UK, this has resulted in a number of international private equity firms entering the market for residential care. Three-quarters of residential care for older people is provided by private, for-profit companies (Brennan et al. 2012), which, because of the increasing elderly population, see this as a good investment. Four large internationally owned companies control almost a quarter of the ‘market’ (Scourfield 2012). Because these companies are motivated principally by profit rather than a service ethos, when they encounter commercial failure the consequences for residents have been very serious. Southern Cross was a US-based private equity firm which by 2011 owned over 750 care homes, representing more than 10 per cent of the ‘beds’ in the UK (Scourfield 2012). In 2011 it ran into serious financial difficulties, and frail, elderly residents, and their families, experienced a period of uncertainty and distress about whether they would have to move elsewhere. In the end another company took over responsibility for many of the homes, but the crisis demonstrated the problems associated with ownership of such services by companies controlled from outside the UK and with little interest in the business other than the potential profit that it offers.

7.4 Supranational institutions and governance

Supranational institutions play an increasingly important part in influencing national social policy. This influence is exercised in a variety of ways and at a variety of levels. At a regional level, the EU plays an important part in distributing resources between member states and directly and indirectly shaping social policy, through its regulations, recommendations and directives. Individual countries in breach of the rules can be held accountable through bodies such as the European Court of Justice. The governance of the EU has created forums which encourage the exchange of ideas and promote the development and evaluation of social policies at a European level. For example, the European Social Policy Network (ESPN) is funded by the EU to ‘ensure expertise and provide rigorous assessments of European and national social policies and to foster a high-quality debate on innovative policy solutions’. It describes itself as ‘a tool to assist the European Commission in the formulation of evidence-based social policies [that] will contribute in particular to the assessment of the National Reform Programmes and the National Social Reports’ (ESPN website).

Beyond the EU, Conventions agreed at a European level, and the institutions created to enforce them, such as the European Convention on Human Rights and the European Court of Human Rights, provide important common benchmarks and standards across signatory countries, which influence policy and practice at a national level. We saw in chapter 4 how the Convention and the decisions of the Court have been important in the interpretation of human rights in relation to religious expression in individual European countries.

At a global level the policies of IGOs such as the UN, the IMF and the World Bank play an important part in directing resources to individual nations and shaping policy through the conditions which they attach to them. Many IGOs are seen as operating in the interests of the Global North, promoting neoliberal policies which give a residual role to social policy and encourage the growth of commodified welfare for those who are better off (Yeates 2012: 204). Global treaties, while not directly enforceable, express the common commitment of signatories to the aims set out in them. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), for example, to which the UK became a signatory in 1989, requires a report every five years on how each signatory has implemented the articles of the Convention. This in turn can be a valuable source of pressure on national governments to address particular policy problems identified by the UN Committee on the Convention on the basis of the national report, such as the treatment of young people in custody, asylum-seeking children and child poverty (UNCRC 2008). The Convention arguably gave impetus to providing greater recognition of children’s rights, which was incorporated into the 1989 Children Act in the form of rights to independent representation of children in legal proceedings.

Other IGOs, such as the OECD, play an important role in bringing about policy convergence between their members through the exchange of information and ideas which they promote. Bringing together comparative information on aspects of the welfare systems of OECD members can act as a stimulus to policy convergence and provides an important channel for dissemination of dominant ideological perspectives.

Globalization has resulted in a proliferation of IGOs with increasing influence, and there has been a corresponding growth in international non-governmental organizations (INGOs). INGOs include a wide range of different kinds of organizations, including trade unions and professional associations, consumer groups and third-sector organizations, such as Oxfam or the Red Cross, that work on international problems of poverty, poor health, humanitarian aid, the environment, etc. These organizations may be involved both in formulating or lobbying for particular policies and delivering services as agents of IGOs such as the World Bank or the UN (Yeates 2012).

Social work, IGOs and INGOs

Historically, social workers have had an involvement both in IGOs such as the UN, and in INGOs. However, this involvement has declined over time as these agencies have focused on humanitarian action and social development while social work in the Global North has become increasingly individualistic and apolitical (Hugman 2010). One study found 37 per cent of the workforce of twenty INGOs were social work-qualified, although most worked in just four organizations, predominantly as programme directors, suggesting that social work’s potential contribution to other areas, such as development, service management and consultation, was neglected (Claireborne 2004). Six organizations did not see social work as relevant to their mission, although they were concerned with many issues relevant to social work, such as human rights, community and leadership development, education and reducing poverty. Most INGOS did not advertise for social workers per se but recruited from many professions, including law, healthcare and teaching, despite some of their key tasks, such as working with survivors of conflicts and disasters, being eminently suited to social workers. It is, however, unclear whether the relative absence of social workers from these INGOs is because they apply for posts but are rejected because they are seen as apolitical micro counsellors, or whether few apply. Social work, however, may be missing valuable opportunities internationally in relation to its broader global social justice and human rights mission, as there is clearly a professional gap.

The work of UNICEF, which is concerned with the well-being of children, whether they have been trafficked, orphaned by pandemics, or are street children or child soldiers, is of particular relevance to social work. Most of its work is conducted in the Global South. UNICEF has employed a number of ‘barefoot’ social workers in remote areas, particularly in relation to child protection. This involves recruiting local women and giving them basic short courses in social work methods and concepts. Social workers are also involved with the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees), primarily dealing with resettlement, repatriation and psychosocial issues relating to asylum seekers, refugees and forced migrants, for whom rape is a major issue.

There are a number of INGOs with a more specific focus on social work. The International Council on Social Welfare (ICSW) has members from more than seventy countries around the world. It works at local, regional and international levels, ‘to advance social welfare, social development and social justice’ (ICSW website), conducting research, disseminating information and lobbying at a variety of governmental levels, working with IGOs and other INGOs. Its wide remit, including social development, means that it has ‘General Category’ consultative status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations (ECOSOC). This means it can contribute to discussions about international economic and social issues and be involved in the formulation of policy recommendations. Two other social work INGOs, the International Association of Schools of Social Work (IASSW) and the International Federation of Social Workers (IFSW), are mainly concerned with social work education and with promoting international social work practice (see section 7.5). Their principal focus on social work as a profession means that they are less involved in international policy making of a broader kind, although both organizations have ‘Special Category’ consultative status with the UN (Healy 2008).

7.5 Professional networks and epistemic communities

Social work as an international profession

The first international conference of social work was held in 1928, led by affluent North American and European women, reflecting the gender and class characteristics of social work at that time (Eilers 2003). The conference was attended by over 5,000 delegates representing forty-two countries. Three international social work organizations were established out of subsequent conferences: the IASSW, the ICSW and the IFSW, which, in different ways, have worked to promote the development of the profession (IASSW and IFSW) and the advancement of social welfare (ICSW).

The journal International Social Work started publication in 1958, through the joint efforts of the ICSW and the IASSW. It initially acted as a source of information for the profession on the work of the UN and of international professional associations, only becoming a more academic publication from the 1970s onwards (Healy and Thomas 2007). The definition of international social work has been contested (Haug 2005; Dominelli 2010; Trygged 2010) with some using the broader term ‘the social professions’ rather than ‘social work’ because of differences in the nature of the work and the professions involved in different countries (Powell and Robison 2007; see also chapter 2). Early definitions in the 1930s and 1940s included working across borders and through international bodies, such as the League of Nations, and international assistance and exchange of ideas through conferences and publications. In the 1970s and 1980s, the focus of international social work shifted to narrower conceptions of comparative social work and cross-cultural awareness (Healy and Thomas 2007; Powell and Robison 2007). More recent definitions draw attention to the importance of international professional action with an acknowledgement of ‘interdependence within a globalising world’ and the use of cross-national comparisons and international perspectives to look at local practice, as well as participation in cross-national or supranational policy and practice activities (Lyons 1999: 12).

A global definition of social work and global minimum standards for the profession were agreed by the IASSW and the IFSW in 2001. The process of arriving at a definition presented significant challenges due to different worldviews (Hare 2004; Sewpaul 2006). Some standards or values put forward were challenged as ethnocentric and/ or colonial, while conversely there was concern that an uncritical acceptance of all normative cultural customs might condone harmful or abusive practices (Trygged 2010). The most recent global definition of social work adopted by the IASSW and IFSW in July 2014 states:

Social work is a practice-based profession and an academic discipline that promotes social change and development, social cohesion, and the empowerment and liberation of people. Principles of social justice, human rights, collective responsibility and respect for diversities are central to social work. Underpinned by theories of social work, social sciences, humanities and indigenous knowledge, social work engages people and structures to address life challenges and enhance wellbeing.

Although some people have argued that human rights discourse is an unwelcome Western imposition, it complements a social justice and needs model because it is entitlement based (Skegg 2005).

Global standards for education and training were drawn up in 2004 (IASSW 2005). These are concerned with protecting service users, encouraging relationships between educational establishments globally, the cross-national movement of social workers and supporting the development of social work education globally. Debates, however, surround the standards’ viability as ‘what is valued academically, epistemologically and ontologically varies between countries and cultures’ (Payne and Askeland 2008: 60), and the Global North has tended to dominate the various international professional associations. Different countries have different criteria for what counts as valued knowledge or evidence, what is ethically or culturally important and what constitutes social work. The IFSW and ICSW presidencies have historically been located in the North, but in 2004 the IASSW elected an Ethiopian, Professor Abye Tasse, as its first president from the South, followed by Professor Angie Yuen from Hong Kong. This could be regarded as a major achievement as it shifted preconceptions about who could lead international social work organizations (Lyons 2006).

In some poorer countries, access to money, books, computers and the internet may be difficult, making it hard for social workers to read relevant literature and attend international conferences to exchange ideas. The IFSW and IASSW have subsidized conference fees and travel costs for poorer countries (Hugman 2010), but this is only one barrier. Both organizations are English-speaking. In countries where English is not the first language, exchange is difficult, and even in European countries there may be language and cultural difficulties, despite similar social and political systems and reasonably widespread fluency in English as a second language (Green 1999). The dominance of the Global North in the discussion of social work education at an international level is partly because social work has a longer history in this part of the world, while it is a relatively new and underfunded profession in many countries in the Global South. The main issues of contention are whether the intellectual and political dominance of the Global North means it is foisting inappropriate values, methods and forms of social work on other countries in an ethnocentric imperialist manner, being unprepared to engage with them as equals and perhaps also learn from them.

Recruitment of social workers from overseas

Many social workers in the UK originate from other countries. High vacancy levels in the UK have resulted in social workers being recruited from overseas (e.g. Ahmed 2007), either arriving in the UK with qualifications gained abroad or gaining a social work qualification after arriving in the UK. Overseas social workers are generally reported being as ‘hard working’ by recruitment agencies, although little research exists examining service users’, employers’ and colleagues’ perceptions of them (Hussein et al. 2010).

Different sources categorize social workers in different ways, making statistics hard to compare. Some sources categorize them by where they qualified, while others group them according to their ethnic/’racial’ origin, and others according to nationality. In 2007, 6,400 registered social workers had qualified overseas (8% of the total); by 2010 this had increased to 6,700 (Carson 2010). Others may have not registered because they could not afford to, or had taken a different career path or their qualification could not be verified as equivalent. One survey showed 19% of social workers registering in 2008–9 were from a non-White ethnic background (GSCC 2010, cited in Laird 2014). There is great regional variation in the concentration of foreign-born social workers, with 48% of the total practising in London and 21% in the West Midlands. Almost one in five of those born outside the UK are European, mostly Irish, with a similar proportion from Australasia and 33% from sub-Saharan Africa (ONS 2006). As mentioned earlier, many immigrants from Eastern Europe and developing nations are employed within the privatized social care sector (Experian 2006), often at a level below their qualifications and skills (Cuban 2008), but this employment may act as a stepping stone to a social work qualification. A high proportion of Black African men who train as social workers initially worked within social care upon arriving in the UK (Evaluation of the Social Work Degree Qualification in England Team 2008).

The push and pull factors for social workers vary according to where they originate from. Social workers from countries with similar welfare systems, such as New Zealand and Australia, fall into two groups: those who come to work in the UK temporarily, early in their careers, and another older, more diverse group with more family commitments and professional experience who often settle in the UK permanently (Evans et al. 2006). One small-scale survey of health and welfare professionals, including ten social workers, found motives for relocation included better pay, anticipated knowledge and skill accumulation which would benefit their career if they returned home, and different travel and professional opportunities (Moran et al. 2005). In another study, social workers, predominantly from South Africa and Zimbabwe, reported smaller caseloads and better wages as key incentives (Sale 2002). Conversely, there are examples of disillusioned overseas social workers with unrealistic expectations of living standards in the UK, one being totally dismayed that he had been placed in social housing (Sale 2002). Another study reported social workers, mostly from Australia, expressing concern about the poor public image of social workers in the UK (Eden et al. 2002). Some overseas social workers also report lowered professional confidence because of different policy, legislation and care systems cross-nationally (Firth 2004).

The number of social workers recruited from outside the UK is relatively small by comparison with the overseas recruitment of health workers (Hussein et al. 2010). Agencies reported that employers preferred applicants from countries similar to the UK. Nevertheless, they recruited from many countries – Africa, Eastern Europe, the Caribbean, Australia, the USA and mainland Europe – but were more reluctant to accept applicants from developing countries because of the brain and skills drain this would constitute for their country of origin. Some barriers associated with employing overseas-trained staff are related to cultural knowledge, norms and sensitivity. These issues render skills transferability more problematic for social work, which requires better interpersonal and communications skills and greater cultural awareness than, for example, professions such as engineering and accountancy. However, the experience of someone who has travelled and been educated across different countries may be particularly useful if they are able to consider cultural and professional differences between contexts self-critically and reflexively, and integrate and synthesize their knowledge to work in a sensitive and informed manner across different situations (Yan 2005, cited in Hugman 2010).

Even though there are now global standards for social work and European legislation standardizing the practice of a number of professions and introducing reciprocal recognition of national qualifications, there may be significant gaps or ‘black holes’ (Faulconbridge and Muzio 2011). A number of commentators have therefore suggested that the employment of social workers who have trained overseas requires rigorous induction and ongoing supervision (Brown et al. 2007; Skills for Care South West 2007). Obtaining visas and procuring up-to-date police checks and overseas references present practical obstacles to their employment and, from a professional perspective, different interpretations of codes of ethics are also a potential problem.

UK social workers working elsewhere in the world

The movement of social workers internationally is two-way. One international recruitment agency reported receiving over 400 expressions of interest from UK social workers considering emigrating for a variety of reasons, including better work–life balance or just a sense of adventure (Carson 2010). Outward migration by social workers from the UK is mostly to English-speaking countries in the Global North such as Australia. For UK social workers working overseas, a number of issues are important. Some work in English-language countries in the Global North but with indigenous peoples, such as Native American Indians in the USA, Aboriginals in Australia, Maori people in New Zealand, and First Nations (Aboriginal) and Inuit people in Canada. European settlers exploited, stigmatized and marginalized these groups and in some countries continue to do so. Some social workers are also engaged in projects in the Global South where cultural norms and languages are very different. Because of this it has been suggested imposition of European social work techniques and practices is inappropriate. Indigenization involves adapting existing models and practices to a new cultural climate, but, due to claims this was an imperialist approach, others propose authentization, authentication or recontextualization. This involves constructing a model of social work which is consistent with the political, economic, social and cultural characteristics of a particular country or culture (Walton and El Nasr 1988; Tsang et al. 2008). It may therefore involve a community social development approach which incorporates some religious or spiritual aspect. In some countries or communities, centuries of aggressive colonization have undermined the capacity of the indigenous peoples to recognize, address or campaign for their own rights and needs, which suggests serious rebuilding, identity, confidence and capacity work is required (Green and Baldry 2008). Yip (2004) also argues that some social work values such as confidentiality, empowerment, self-determination and autonomy, are Eurocentric and individualistic. They are therefore problematic to implement in the Global South where other values, such as harmony, family stability and responsibility, predominate.

Hugman (2010) compares Yip’s analysis of a Chinese male/female DV scenario with a similar case examined by Healy (2007) involving a Vietnamese immigrant settled in the USA. Both Yip and Healy concur that DV is morally wrong. Yip asserts the way to persuade the Chinese woman to leave her husband is to focus not on her needs/rights or the wrongness of his actions but on the welfare of her daughter, as this is consistent with Chinese values. Healy conversely is more concerned with cultural values being misappropriated to elevate one person’s human rights and deny another’s, and indeed norms of family harmony and societal stability would seem to be an anathema, if they are conditional on colluding with or indirectly condoning domestic abuse. Infanticide often occurs in very poor societies because of limited access to contraception or terminations together with insufficient resources to feed and care for all children born (see Scheper-Hughes 1992). This may be compounded by patriarchal ideologies which exacerbate female infanticide by culturally subordinating girl children, as occurs in China and India (Green and Taylor 2010). Some abusive cultural practices therefore need to be located within wider social justice arguments which factor in cultural understandings and deprivation, disadvantage and poverty which may corrupt and corrode cultural practices.

Cross-national collaborations and exchanges

In the UK most collaborations and exchanges between social workers since the 1970s have been at a European, regional level as opposed to a global level, mainly funded by dedicated European monies. These often include cross-national comparative research projects on specific issues such as the balance between therapeutic support and legal intervention with regard to child sexual abuse (e.g. Green 1999), and practitioner and education exchange visits, exemplified by the ERASMUS and TEMPUS programmes. These projects have, however, tended to be concerned with comparisons of policy and practice at the micro and meso level, across small numbers of countries, with relatively little focus on structural or wider global issues.

Practitioners and academics can learn much from published cross-national research and debate, now included not only in dedicated regional and global journals such as International Social Work and the European Journal of Social Work, but also in Social Work Education, which is subtitled an ‘international journal’, and Britishbased journals such as BJSW and Child and Family Social Work. These regularly publish articles from overseas scholars and/or refer to research conducted in other countries as a comparator to UK research. Despite this, few articles refer to the interconnected and interdependent global context and/or to social development. Most students mainly draw on literature concerned with the UK, and very occasionally the European context, because their education, training and practice encourage this. However, international social work research, hitherto under-utilized, can help practitioners learn from and adapt other countries’ policies and practices (Hokenstad and Midgely 2004). Such research includes: (i) supranational research, conducted in one country but drawing on literature from others; (ii) intra-national research, primarily associated with studying immigrants, asylum seekers and refugees; and (iii) trans-national research, comparing different countries (Jung and Tripodi 2007). The study of different countries’ welfare regimes (see chapter 2) and Humphreys and Absler’s analysis of social work responses to DV across nations, time and history (see chapter 3) are two good examples of transnational research.

7.6 Conclusion

Globalization, understood as the complex interactions between economic, technological, cultural and social forces across the world, has reduced the power of individual nation states to control economic and social policy and has given rise to new social problems which in turn have important implications for social work. Greater population mobility across the globe, prompted by global inequality, conflict and natural disasters, combined with attempts to restrict immigration in the countries of the Global North, have drawn social workers into the policing of national borders – for example, through their involvement in age assessment of child asylum seekers. Such developments raise new ethical dilemmas for the profession about how to balance legal duties with social justice and a humanitarian response to need. More restrictive immigration legislation, introduced as a response to increased global population mobility, has given rise to new criminal trafficking networks which expose those trafficked to abuse and exploitation. This again raises questions about balancing the care and protection of victims of trafficking with the enforcement of immigration legislation. Victims may be deterred from seeking help from social workers, amongst others, because they feel caught between two equally undesirable alternatives: continued exploitation or deportation.

Global care chains link migrants working in the UK to extended families living in other parts of the world, who are dependent on them for financial support. Many of these migrants are carrying out care work in the UK which elderly and disabled people depend on for their well-being. Social workers need to have an awareness of the complex interdependencies which affect the care and support of others, both in the UK and elsewhere in the world. The Global North tends to benefit from these care chains at the expense of the Global South, with skilled labour, such as nurses, attracted to the UK to meet labour shortages. Although remittances make an important contribution to the home countries of many migrants, these countries also lose both the skills and the unpaid caring which these migrants would otherwise contribute in their country of origin.

Although social work has a long history of international exchange of ideas, which has been promoted through various international bodies since the late 1920s, a global definition of social work and global standards for the education and training of social workers were only introduced at the beginning of the twenty-first century. The creation of new supranational governmental and non-governmental institutions in response to economic globalization has made it increasingly important for social workers across the globe to speak with one voice, and to have a means of making representations to IGOs and INGOs. The process of arriving at such global definitions and standards is a difficult one, which has necessarily involved recognizing and accommodating cultural and resource differences between the countries of the Global North and those of the South. Similar issues of cultural adjustment and responsiveness arise when social workers go to work abroad, whether this is coming to work in the UK or going from the UK to other parts of the globe.

Discussion questions

- Discuss, using relevant examples, why an understanding of globalization and the wider international context is important for social workers operating in one specific locality or nation.

- What tensions and dilemmas currently confront social workers working with asylum seekers and illegal immigrants? Can these be resolved or managed? If so, how?

- How might the ability to engage with European and international human rights legislation help social workers to practise in a way more congruent with upholding key professional values and ethical mandates?

- Outline and discuss the ways in which globalization has impacted upon both the social work and social care labour force in the UK and on the changing service user population.

Further reading

- British Journal of Social Work (2014) ‘Special Issue, “A World on the Move”: Migration, Mobilities and Social Work’, 44 (supplement 1).

- Hugman, R. (2010) Understanding International Social Work: A Critical Analysis, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lyons, K. (2006) ‘Globalization and Social Work: International and Local Implications’, British Journal of Social Work, 36, 365–80.

- Yeates, N. (2012) ‘Global Social Policy’, in J. Baldock, L. Mitton, N. Manning and S. Vickerstaff (eds.) Social Policy, 4th edn, Oxford: Oxford University Press.