CHAPTER 2

Organizing the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association

If the Government had the right to free us she had a right to make some provision for us and since she did not make it soon after Emancipation she ought to make it now.

CALLIE HOUSE

(1899)

CALLIE HOUSE’S LIFE was transformed when she stepped into public view as an activist working for the pension cause. Sociologist Alden Morris has described how the 1950s and 1960s civil rights movement found a base and leadership in the church, the only place where blacks could meet freely with a minimum of white control. This was not new. Throughout the period since Reconstruction, African Americans used the church as the center of community action, and the reparations movement found a home in church, too. House and Dickerson established their headquarters in Nashville, which had become the black church hub of the South, including the publishing operations of the two largest black religious denominations: the National Baptist Publishing Board and the African Methodist Episcopal Church Sunday School Union Publishers, both located there.1

The city of about 76,168 people in 1890,40 percent of whom were African Americans, was just thirty miles from Murfreesboro, the Rutherford County seat. It may not have been the most obvious venue for a poor people’s movement despite its attractiveness as a transportation hub and its history as the place where Pap Singleton’s exodus had started. A sizable African-American middle class grew around Fisk University and two other local black private colleges and at Meharry Medical College and the publishing houses.2

Using the contacts Dickerson had established from his work with Vaughan, House and Isaiah Dickerson traveled throughout the former slaveholding states to enroll members and organize local chapters through the churches. In the years before his death in 1909, Dickerson’s experience was invaluable to House. They went on the road, organizing the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association and receiving immediate and enthusiastic responses from African Americans. At the grassroots level, the ex-slaves, who were at the lowest economic level, embraced what was essentially a poor people’s movement. Old and disabled by so many years of manual work, bad diet, and no medical care, these people understood and supported the association’s demand for pensions to compensate for years of unpaid labor. The effort also was endorsed and supported by local preachers, and the association’s membership grew rapidly. Part of the association’s program included offering medical and burial assistance. It also offered a democratic structure in which local people had control and a voice, at a time when blacks were practically disfranchised or on the verge of becoming so throughout the South.

Soon after House began the Ex-Slave Association work, she and her children and her brother and his family moved to South Nashville, where she made her home for the remainder of her life. Despite organizing work, she still described herself as primarily a washerwoman and seamstress. House’s sister Sarah and her family continued to live in Murfreesboro.3

Her brother, Charles Guy, worked as a porter and first boarded in South Nashville with House at 1003 Vernon Street, near Eighth Avenue between the reservoir and the capitol. Later he would move his family, consisting of his wife, Mandy, or Amanda, and daughter Annie Mary to Nashville. The homes in House’s neighborhood were single or double tenant, with a living room, bedroom, and kitchen adjacent to each other in a row. Because it was possible to stand at either end and look straight through, such homes were named “shotgun” houses.4

In her work as a washwoman, House was like many African-American women of the time, either married or widowed with children, who took laundry-work into their homes. Generally, before she married, a woman would work as a maid or cook in a private home. After she had children she stayed home and took in wash. Washing machines did not appear for home use even for the wealthy until about 1914. Consequently, these women washed bedding, towels, and every item of clothing by hand; they also ironed for an entire family each week. The pay sometimes totaled about $2. At the time rents or mortgage payments in the neighborhood were $5 to $12 a month, thus such women had a difficult time earning enough to maintain even a meager existence. In addition, women who worked at home so they could care for their children did not receive the food scraps to take home that women working as domestics outside the home used to help feed their families.5

African-American women washed their family’s laundry and took in washing from poor and well-off white families. This woman had to boil the clothes and constantly bend to stir the wash kettles and lift soaking wet, heavy bedding.

About the time House moved to Nashville, gasoline washing machines became available, although clothes first had to be soaked in kettles of water heated over a wood fire. However, poor people could not afford the washing machines, and even with the advent of commercial laundries, poor and well-off white women continued sending their clothes to black women’s homes for laundering well into the twentieth century. Race remained a significant issue even in getting clothes washed, and Nashville commercial laundries thought it wise to advertise on streetcars and on the sides of its delivery wagons “No Negro Washing Taken.” Washerwomen purchased soap, if they could afford it, or made lye soap from pork grease saved from cooking. They scrubbed the clothes on washboards, used bluing for whitening, and made starch by boiling flour. They heated irons on the stove and removed excess starch from the clothes’ surface by running the iron back and forth across salt poured on paper covering the ironing board. The women’s hands were reddened from the harshness of the soap, and they worked with constant pain from bending over to stir the wash kettles and from lifting soaked, wet, heavy bedding. This method of doing laundry by hand remained unchanged from House’s day until the 1950s for poor African Americans in Nashville, including my own family. In the 1940s, in Nashville, the mother in the family next door to us took in laundry and washed on a washboard, much as House had done but with the addition of a recently bought hand wringer.6

House and her brother, Charles, like their neighbors, were the first generation of African Americans to reach maturity after the abolition of slavery. Their parents were the first generation to experience old age in freedom, but their work conditions remained harsh. Although the 1890 Nashville City Directory listed four African-American women as managers and owners of boardinghouses, three as dressmakers, and nineteen as sick nurses; fifty-five were listed as laundresses—washerwomen. The 1910 and 1920 Censuses reported most women in the neighborhood as either domestic workers or laundresses. The men worked as live-in or live-out chauffeurs, laborers, porters in department stores and hotels, bootblacks in barbershops, packers in factories, and an occasional plumber in a plumbing store or a carpenter or plasterer working for a contractor. Some of the men, such as House’s brother, Charles, also worked as itinerant Primitive Baptist preachers. They felt called to preach, although they had neither congregation nor church income.7

To a casual observer, Nashville after the Civil War appeared as a provincial, unpretentious southern city. Most of the city’s area lay within a two-mile radius of the capitol. Poor people lived in the streets and lanes around Capitol Hill. The waterfront and the railroad depots dominated their views. Among the dirty houses, trash-filled streets, taverns, and brothels, the Republican Banner cried, “Our city looks like a pig pen, and is profitable to the owners of the city scum, but it speaks badly for our notions of health and cleanliness.”8

House’s neighborhood evolved from Edgehill, one of five camps the Union Army had established for the freedpeople— called “contraband of war” until legal abolition—in Nashville. South and below the capitol on the hill, House’s neighborhood bordered “Black Bottom,” with Lafayette Street, a pathway cut through to give better access to Murfreesboro Pike (Eighth Avenue South), the northern boundary.9

The old city cemetery and Fort Negley, built by contraband to protect the city from the Confederates, the Louisville and Nashville railroad yards, and white residents between the tracks and Ninth Avenue South, served as the eastern boundary of Edgehill. Fort Negley is still standing. Near Eighth Avenue South, another pocket of blacks lived in Rocktown. The entire South Nashville black neighborhood was within walking distance—about a mile—from downtown.10

The freedpeople developed their neighborhoods from the camps, where they at first lived in shacks. Soon they built wooden shotgun houses. Nashville had gaslit streetlights after the Civil War, and electricity, waterworks, and a streetcar system came before 1900. However, working-poor African Americans usually had no plumbing, electricity, or gaslight until well after the turn of the century. As late as the 1940s, in that same South Nashville neighborhood, the utility services still did not come to our part of town. Our poverty and blackness made us easy to ignore. At night, we still depended on light from oil lamps or the burning fireplace that was the only source of heat. Sparks left telltale scars on the legs of anyone who sat or stood too close to the fire, indelibly marking a shared experience of need and deprivation. In this neighborhood, House and her family made their home and eked out a difficult existence.

In South Nashville, where House’s family and other working-class blacks who had started their lives in the contraband camps lived, the new industries created a noxious environment. Their housing subsisted with the noise and pungent smells of four mills, breweries, and chemical processing plants near the rail yards.11

Nashville’s overall cityscape changed fundamentally between the Civil War and the 1890s, when House moved to town, as a result of industrial and business transformations. Annexation, the acquisition of Edgefield in 1880 with a 65 percent white population, and streetcars to outlying regions shifted the population in the city, making it blacker, while the overall population of the legal metropolitan entity became less black. The process of annexation has led to continued dilution of the black population in the metropolitan Nashville area today. By the turn of the century, the city had become a major commercial center and wholesale marketplace in the South for industry, banking, and professional services. The rail, water, and turnpike facilities gave Nashville an advantage over most other southern cities. Once the home of the upper class, the city’s uptown core became a more concentrated commercial district that pushed most residential uses outward as it expanded.12

A contrast between rich and poor in the 1890s. (Top) African-American children playing marbles. (Bottom) William Harding Jackson, Jr., a son of William H. Jackson of Belle Meade Plantation, in his pony carriage in front of the mansion.

The adult freedpeople in House’s community continued to labor at the lowest-paying work as they aged or had to be cared for by their poor, hardworking children. Most rented their homes, though rent and mortgage payments ranged from $5 to $12 a month and absorbed most of their income. Callie House and other washerwomen, with the $2 a week they earned for their labors, struggled to make ends meet and keep a roof over their heads. Poor African Americans could not afford more than a diet of hoecake and greens, often without meat and similar to what they had eaten during slavery. Their diet, along with polluted water, outhouses, poor heating, and minimum medical care, continued to erode the quality of life for poor black Nashvillians. When the smallpox epidemic of 1895 killed large numbers of black children, the city quarantined the African-American neighborhoods. The city’s health officer called repeatedly and unsuccessfully for attention to the acute need for medical services for black citizens. While white health conditions improved, high comparable death rates and infant mortality remained problems in the black community.13

Tennessee’s segregation law of 1881, the first in the South, affirmed the racial subordination that already existed. By the 1890s, in Nashville as in Rutherford County, Callie House and other African Americans felt deeply the effects of Jim Crow. Men could still vote legally, but they faced powerful whites who enacted poll taxes and shifted polling places and registration lists to keep black men from the ballot box. Under Jim Crow, the city provided separate fairgrounds for blacks and whites, and the trolley cars and streetcars separated African Americans from whites. Railroad stations had separate waiting rooms, and saloons and brothels were separate or segregated. Amusement parks had separate areas within them for African Americans. Ostracized African Americans developed the habit early of organizing mutual aid when they established burial assistance associations that used the Mt. Ararat and Greenwood cemeteries to bury their dead next to, but segregated from, the white cemetery.14

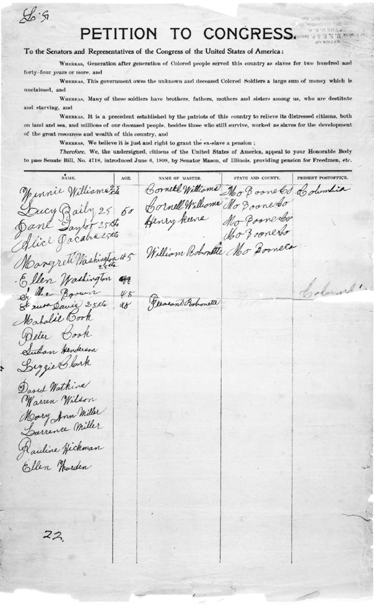

Ex-slaves in other communities fared no better, which is why they, too, eagerly joined the Association. Mrs. House and her colleagues worked to establish chapters across the former slaveholding states, working separately from Vaughan. House and Dickerson encouraged members to sign petitions to Congress and held conventions culminating in the chartering of the association under the laws of Tennessee in Nashville in 1898. House and Dickerson identified members to apply for charters in each state where they organized. The state chapters recognized local lodges and councils.15

The five incorporators were apparently all Primitive Baptist ministers, although confirmation for one of them, W H. Gosling, has not been found. Reverend Nathan Smith from Bransford, Tennessee, who according to the 1900 Census was a fifty-year-old farmer, lived with his wife and stepson. He owned their farm and worked the property with his stepson. Luke Mason, the fifty-year-old pastor of Lewis Street Baptist Church, who made his living as a painter, and Squire Mason, probably his brother, a sixty-two-year-old shoemaker who had operated a downtown shop catering to whites for almost twenty years, joined the group. Both their wives “kept house,” which meant they stayed at home and did not, insofar as the Census taker could tell, take in laundry, and they each had five grown children.16

Callie House and the founders of the Ex-Slave Association echoed Samuel Cornish and John Russwurm when they published the first African-American newspaper in 1827 announcing “to Long Have other Spoken For us.” House and the other leaders at the first convention, in Nashville in 1898, asserted that they could better advocate their own cause: “Thirty-three years of advantages of schooling has prepared the Negro to look out for the welfare of his race; and he can better foster the cause of his race—he has the brains to do so and race pride and manhood are needed at the front; race loving men and women too.” House, believing that the development of disconnected small pension organizations would weaken the effort to gain legislation, declared unity as a goal of the association. She asserted, “Let us consolidate all ex-slave organizations and bring to bear upon the lawmakers of the country which we labored so long to develop every degree of influence within our power.”17

House and the association officers explained to the membership that repeatedly introducing legislation, submitting petitions from old ex-slaves, and engaging lobbyists would someday gain a committee hearing and then perhaps a vote. Standing before the poor and working blacks who had elected her to office, Callie House expressed both the optimism of the moment and the practical view learned from years of black struggle. She told members that grassroots petitions and lobbying would someday gain victory in Congress for their efforts, but the bill would not pass soon. The struggle would be necessarily long and problematic, but the principle of debt owed should never be abandoned.

Unlike Vaughan’s operation and other mutual assistance fraternities, the association opened its membership to all, emphasizing that their organization had no “secret grips or passwords.” The association’s simple goal was to put the name of every ex-slave on a petition asking Congress to pass a bill providing pensions. Surely the plight of these old African-American men and women, aging, ill, and impoverished from hard work and ill treatment during slavery—many of whom were the relatives of the white middle class—deserved recognition. These people’s unpaid labor and service had continued during the Civil War as they had served as washerwomen, nurses, and laborers repairing levees, widening drainage ditches, and building fortifications. Their cause should compel sympathy and money when their status was compared to that of Union veterans, who, even if they had served for only ninety days far from the battlefield, could claim an inability to perform manual labor, whatever their occupation or income, and receive a government pension of $12 a month.18

The Association placed great emphasis on self-help. Local chapters were required to use part of the dues to pay for the burial of members and to provide mutual assistance in time of sickness and need. At the time such private aid organizations were the only help available for poor African Americans. These functions did not depend on the success of the pension legislation but would build solidarity in the group. In the meantime, the association would keep the reparations claim before the public, declaring it a matter of justice for African Americans.

The Ex-Slave Association was unusual in its origins and purposes. Sociologist Rebecca Ash and other scholars argue that movements have either radical change or service goals. The ex-slave movement had a dual mission from the beginning: the attainment of federal pension legislation and mutual aid to poor members. Although the controversial nature of the pension demand brought the association legal troubles, its mutual assistance activities accorded with the national self-help emphasis of the late nineteenth century.

African Americans had long been in the habit of forming mutual assistance associations, providing help when government refused to help. For African Americans, such mediating institutions historically provided the only available social assistance. Government provision of social services to the African-American community is a relatively recent development.19

Thousands of ex-slaves signed petitions like this one to Congress asking for pensions for their forced labor during slavery. Those who could read and write made sure that those who could not were included.

In 1787, in Philadelphia, blacks led by Richard Allen and Absalom Jones withdrew as a body from the prejudiced whites of St. George’s Church and formed the Free African Society, the first African-American mutual-aid society. The members pledged to help one another in sickness and death and to provide for widows and children of the deceased. They also purchased a plot to use as a burial ground. Mutual-aid societies, often connected with a church, spread rapidly in northern urban communities and among free Negroes in New Orleans, Charleston, and other southern cities. In this period, long before the Social Security Act of 1935, the societies aided the elderly or disabled and provided a decent burial for the impecunious.20

With Emancipation, the concept of the benevolent association grew rapidly until it was employed by Mrs. House and the association. It was one component of the broad effort at community care among African Americans, which included secret societies, homes for children, old-age homes, and a flexible family system for individuals throughout the life cycle. At the end of the nineteenth century, when the Ex-Slave Association began, a freedman or-woman emancipated at age thirty would have been sixty-seven. Among the first generation of African Americans to enjoy freedom, large numbers were in their sixties, seventies, and eighties and unable to work at manual labor because they were suffering from a variety of ills, some stemming from the hardships endured during slavery. The rapidly aging members overwhelmed local benevolent societies. The crisis underscored the need for both parts of the Ex-Slave Association’s agenda of mutual aid and pensions.21

In 1898, when the Ex-Slave Association sought its charter, Nashville already had a number of benevolent institutions. The 1895 smallpox epidemic and the continuing admonitions of the public health officer caused the white Ladies’ Relief Society to increase help to poor whites and to challenge black leaders to do the same for African Americans. Thirty leading African-American women formed the Colored Relief Society for this purpose. Other relief organizations, including the Nashville Provident Association, founded in 1865 to give firewood and soup to needy freedmen, still operated. Nashville’s African-American churches, like those elsewhere, offered benevolent auxiliaries. The association’s mutual aid filled a crucial gap in these disparate and generally underfinanced services for an aging and ill population. Suffering from poverty, bad diet, injuries from abuse during slavery, and hard work since, many ex-slaves over the age of seventy had a difficult time making their battered bodies continue to work at the hard-labor jobs available to them. Moreover, the poverty of the “first freedom” generation of African Americans meant they could not sustain both their older relatives and their own families.22

Nashville’s better-off African Americans put some resources into helping the poor, but they showed more concern for civil rights and opportunities than for addressing poverty. As Jim Crow and disenfranchisement became law and the lynching of African Americans became common across the South, they also took their toll in Nashville. Indelibly etched in the minds of local ex-slaves was the 1892 lynching of Eph Gizzard, who had been accused of raping a white woman. On April 30, while the city was still in the grips of the seventeen-foot March snowstorm, the largest in history, Gizzard was hanged by a mob right downtown at 2:40 P.M. on the Woodland Street bridge.23

Most of Nashville’s frustrated African-American leadership ignored pension seeking to spend their energy and political capital on other concerns where they believed they could make a difference. For example, the year before House and others met in the city to promote reparations, the elites worked hard to gain participation in the Centennial Exposition of 1897, held to mark Tennessee’s one hundredth birthday. Preoccupied with their own image as an educated group, the elites thought it valuable to join the exposition even though they would have to accept segregation. Northern middle-class African Americans, far from the Jim Crow environment, objected to the strategy, earning the resentment of their Nashville counterparts. On February 27, 1897, the Nashville American criticized the only African American in the Massachusetts legislature for complaining that public funds should not be used to pay the expenses of Massachusetts officials visiting the Tennessee fair because of its segregation. In a period when House and most other African Americans lived in rental housing without light or heat except for a fireplace, and worked at low-wage, laborintensive jobs with which they could barely make ends meet, the business and professional leadership fought for inclusion in the exposition and boasted that they’d achieved a Negro day at the fair. In the end, the emphasis on culture, sketches, oil paintings and drawings, musical compositions played daily by a pianist, and carvings by Negro sculptor G. R. Devans of horns and walking canes engraved with pictures of Civil War generals contrasted sharply with the real-life social and economic problems of poor African Americans. When the exposition was over their problems remained.24

But it was in 1895 in Atlanta, on precisely such an occasion of proud cultural displays, that Booker T. Washington gave his racial accommodationist speech:

“In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the five fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.” He continued, “To those of my race who depend upon bettering their condition in a foreign land or who underestimate the importance of cultivating friendly relations with the Southern white man…I would say ‘Cast down your bucket where you are.’” His widely reported Atlanta Exposition speech essentially amounted to telling African Americans to stay in the South, work hard, and accept segregation to show they “deserved” citizenship rights someday. Washington’s speech made him white America’s favorite race leader and gave him control of African-Americans’ access to money and power.25

In Nashville, the Tennessee Exposition officials followed the example set in Atlanta to establish a segregated “Negro Department” at the beginning. They appointed a committee chaired by the city’s most prominent African-American Republican leader, James Napier, a former member of the city council who held various patronage posts and saw to it that his friends did so as well. As chief of the Negro Department, Napier’s committee included fifteen of the most prominent African Americans.26

With this nod to Napier by the state’s leading white businessmen, Nashville’s African-American leadership determined to show its agreement with the philosophy of Booker T. Washington. It publicly accepted segregation as a road to equality and applauded the selection of Washington as a speaker. It also seized the opportunity to display the “progress” African Americans had made since emancipation. When Napier was later forced to resign because of ill health, he publicly underscored the value of this opportunity to the community. His resignation letter pointed out that since Emancipation “intelligent” blacks had “rapidly increased in numbers” and the “Negro Exhibition Hall” would prove their progress. Under the leadership of Richard Hill, a “Negro” schoolteacher and the son of “Uncle John Hill”—a favorite fiddler for wealthy white parties, black Nashvillians designed and constructed the “Negro Building,” which included a segregated first-aid station and other facilities for their use. Hill told African Americans that they were “on trial.” He said, “The American people have spent no small amount and energy for our intellectual and moral training. Many are now asking ‘What have they amounted to?’” If they failed to exhibit their accomplishments, “It will be our everlasting shame.”27

Each college, university, and other acceptable African-American organization in the city enjoyed a special day for its segregated exhibits. The managers also set aside June 5,1897, as “Negro Day” to enjoy the entire fair. From all over the state blacks came to Nashville to visit the site, and schools, churches, and civic organizations marched in the parade. Both races, kept segregated, attended affairs involving Republican president, William McKinley, the governors of some twenty states, and the Booker T. Washington speech on Emancipation Day, September 22, 1897. The white Nashville press usually restricted coverage of African Americans to reports of lynchings, vignettes and cartoons on the laziness and ignorance of blacks, or articles on the “misguided” efforts of African Americans who challenged the color line. For the exposition, the papers enthusiastically reported on the “Negro Building” and African-American activities. Leaders believed they had put their best foot forward at the fair and avoided “everlasting shame.”28

Nashville’s class of well-off African Americans concentrated on making gains in business and the professions within the segregated black community. Privately, like Booker T. Washington, they worked to remedy black exclusion from politics and were finally somewhat successful in 1911, when a black lawyer, Samuel P. Harris, was elected to the city council. He was the first African American elected since Napier’s defeat in 1885. Poor and working-class African Americans such as Callie House and association members interacted with this group of blacks only in the course of business, such as in the incorporation of the organization.

The National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association charter stated that the Association would work to unite African Americans and “friends” together in the cause. It made clear the dual mission of the organization. The association would collect petitions and lobby to pass the pension bill. However, mutual assistance was of equal importance. Local chapters would do “whatever is necessary in the way of charity and benevolence by aiding of its members in distress in sickness and in death and in looking after the interests of all.”29 Members contributed ten cents monthly to finance their ambitious goals.

Although chartered by Primitive Baptists, the church of working-class blacks, the first official association convention, at which Mrs. House was elected assistant secretary, took place at Gay Street Christian Church, a prominent Disciples of Christ congregation. The church, founded in 1824 as the “Negro congregation” of the white Vine Street Christian Church, trained and nurtured some of the most outstanding African-American church brotherhood leaders, including Preston Taylor, who became a nationally admired Disciples of Christ leader. Taylor was closely associated with James Napier and other well-off African-American Nashvillians. Taylor involved himself in every civic endeavor and enterprise in Nashville and the surrounding area and he introduced Booker T. Washington at the 1897 Centennial Exposition. He also served as parade marshal on “Negro Day.” The Gay Street Church provided a quite respectable venue, giving the association credibility. The pastor serving the successor church today could find no records from this period but suggests that Gay Street became the venue for the association convention because of Preston Taylor’s interest in every type of community involvement.30

Following the association’s first postcharter convention, from November 28 through December 1, 1898, the newly elected assistant secretary, Callie House, reported to the membership that they had proudly thanked local Republican leader James C. Napier and Reverend Richard Henry Boyd for their attendance. Boyd’s presence was important because he was the most successful Baptist minister, the founder of the National Baptist Publishing Board, and financier of the local black newspaper, The Globe. The association officers knew that the presence of Napier and Boyd at their first official convention could signal important political support for the pension cause. Napier’s future father-in-law, for example, was John Mercer Langston, who had vocally opposed the pension idea while in Congress.31

In the materials she sent to the state and local chapters and after the convention, House reported that the convention had acknowledged, both at the meeting and in its literature, the role Vaughan had played by first suggesting pension legislation. She also candidly described a rift in the movement blamed on Vaughan’s attempt to anoint Hill, who the association did not deem any more likely than Vaughan to garner grassroots support. Although “slanderous circulars” and competing efforts had ensued, the association now asked that any existing organization affiliate with it to “consolidate under one head.”32

The delegates who went to Nashville for the meeting made clear their support of pension legislation and what they called the “Bodkin Bill,” a measure introduced by Democratic congressman Jeremiah Botkin of Kansas in March 1898. The bill gave ex-slaves homesteads of forty acres for individuals and 160 acres for a family. The families would also receive initial capital from a legacy or commissary fund that included uncollected deceased soldiers’ pay and pensions. This bill, which did not pass, reiterated the original promise of land to the freedmen that had remained unfulfilled.33

Notice of the Ex-Slave Association 1898 convention at which Callie House was elected assistant secretary.

The association announced opposition to a Senate bill designed to appropriate $100,000 for a National Home for Aged and Infirm Old Ex-Slaves in Washington as out of line with its objectives. The appropriation would come from funds in the Treasury, owed to deceased black soldiers but unpaid because wives and children were not aware they existed and did not apply or could not provide legal documentation of their relationship to the deceased. The bill’s sponsor, Senator George Perkins, Republican of California and chairman of the Committee on Education and Labor, stated that as of July 27, 1895, the funds amounted to $230,018.84 even though the bill expressed a willingness to spend less than half that amount. A group of “the very best and most influential colored people in this country” had been asking senators and congressmen to introduce the bill since 1893. Their petition included leaders such as African Methodist Episcopal Church bishop Alexander Walters, chairman of the Afro-American Council, a civil rights protest and advocacy group; the four most prominent Washington, D.C., ministers, Francis Grimke of Fifteenth Street Baptist Church, Walter Brooks of Nineteenth Street Baptist Church, J. Albert Johnson of Metropolitan A.M.E. Church, and J. A. Taylor of Shiloh Baptist Church; and Calvin Chase, editor of The Washington Bee, one of the most important black newspapers. Those leaders had created a corporation and arranged to buy land to build the home. These men thought this appeal was more likely to receive support from Congress than any other proposals to help poor blacks.34

In the House debate on the bill, Congressman Ernest Roberts, Republican from Maine, stated, “There is no question that the aged and colored people who once were slaves are more subject to destitution and require charitable aid more than any other class of people in the United States.” Since the government did not establish charitable institutions, it should assist those who would. He asserted that in the District of Columbia, the only available public facility, in the basement of the Children’s Asylum on Eighth Street, could accommodate only ten persons at a time. Therefore, it made sense to help blacks care for the “needy and aged of their own race,” using funds that belonged to African-American soldiers.35

Even though the convention liked the idea of the home, which to them seemed as unlikely to pass as the pension bill, it was opposed, according to Callie House’s report to the members, because the small size of the proposed facility was grossly insufficient. In addition, members believed it would “block the passage” of reparations “for all time to come.” Convention participants decided, instead, to continue their efforts to pass the Mason Ex-Slave Pension Bill.36

The tone of the congressional debate supported the exslave delegates’ conclusion that the Home for Ex-Slaves Bill would not pass. Representative Joseph Cannon, Republican representative from Illinois and chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, explained that in reality no surplus funds existed from unclaimed pay and bounty for white or black soldiers because the Congress made appropriations only when needed. The bill therefore consisted of “mere leather and Brunella…mere deception, mere sticking in the bark-buncombe, so to speak. This bill would do the manly and honest thing if it said, there is hereby appropriated $100,000 to build this home.” Also, he saw no reason to cut off the possibility of claims by black soldiers’ relatives in 1903 unless claims were also ended for the relatives of white soldiers. They might make claims later. He pointed out that “claims agents are writing all over the country.” They are “hunting up everybody to whom we owe anything and three times as many bodies to whom we do not owe anything. They are lively ducks.” They might still identify claimants.37

Reverend Dudley McNairy from Nashville, one of the charter incorporators, was elected president of the Ex-Slave Association at the 1898 convention. The convention instructed him to go to Washington to lobby for the Mason Bill.

Democratic representative John Gaines from Tennessee objected. He predicted that the home would attract the poor from different states to the District of Columbia and become a burden, making the U.S. government “a poor house.” Georgia Democratic representative Charles Bartlett pointed out that the funds “did not come altogether—possibly in very small part—from colored soldiers of the District of Columbia.” They came from “various parts of the union.” But now the advocates wanted to use it “for the benefit exclusively of persons residing in or near the city of Washington.” Roberts answered that it would be located there but for the “people of the whole United States.” Committees in both houses of Congress reported out the Home Bill, but it did not pass.38

Most of the convention time was spent on deciding how to move the pension legislation forward. In addition to electing Mrs. House assistant secretary, the convention delegates named Reverend Dudley M. McNairy, one of the charter incorporators, president, and Isaiah H. Dickerson general manager, “to whom all communications should be addressed.” At the end of the meeting, the delegates instructed McNairy to go to Washington to lobby for the bill, which they persuaded Senator Edmund Pettus, Democrat of Alabama, to reintroduce. It repeated the provision of earlier bills: a pension of $15 per month and a bounty of $500 for each ex-slave seventy years and older. Those under seventy would receive $300 as a bounty and $12 per month until they reached the age of seventy. Those less than sixty years old would receive a $100 bounty and $8 a month until they reached age sixty. Those less than fifty years of age would receive $4 per month and then, at age fifty, $8 per month. Ex-slaves and those legally obligated to take care of those who could not care for themselves were eligible for the pensions. McNairy expressed the hope that the “many ex-slave organizations striving to secure the enactment of the Vaughan Bill [Mason Bill]” would affiliate with the association so as to “consolidate under one head.”39

This early certificate of the Ex-Slave Association does not mention mutual assistance.

The constitution and by-laws and the report of the convention included photographs of the officers, including Callie House. The membership certificates boasted a picture of Senator Mason of Illinois and, in one corner, the words “$500.00 bounty,” the amount immediately payable, in addition to $15 per month, to those seventy or older if the bill passed. The certificate did not explicitly reiterate the language in the charter concerning the mutual benefit mission but spoke only of efforts to aid “the ex-slave movement and raise funds to promote the passage of the bill.”40

The 1898 national convention approved the issuance of these formal legal documents of the Association, including photographs of House and the other officers.

House’s first letter to the membership, printed in the convention proceedings after her election as assistant secretary.

National African-American newspapers and leading politicians and activists did not change their views concerning pensions just because the effort became black-led and successful. While the white press derided the movement as ridiculous and fraudulent, these leading African Americans either ignored it or criticized it as a distraction from the struggle for political rights and a hopeless cause. House often expressed outrage at their refusal to provide publicity that would help to organize the movement. These leaders’ efforts to gain land and education aid and even election protection in the Congress had failed miserably. Yet they would not even try another avenue for relief for poor black people. From her perspective, “The most learned negroes have less interest in their race than any other negro as many of them are fighting against the welfare of their race.”41

Despite these divisions between better-off, better-educated African Americans and the poor freedpeople who supported pensions, the association had organized successfully and was rapidly growing. The fees it collected, House explained, paid “expenses of the movement in printing literature and postage on literature sent out to notify our conventions and meeting for speaking and to pay traveling expences [expenses] and support of men and women who are giving their whole time to the movement.” The association also spent the funds to “send men to Congress as delegates to present our petition when Congress meet[s] the first Monday in December.”

In addition, the local chapters used the ten cents’ monthly dues they collected to pay for “places to meet at and to help old and decrepit members to render mutual assistance any way they see fit.” Callie House expressed pride in the convention’s work as she circulated the minutes to the membership. She was especially honored that she had been “elected by the people as an officer in this organization which belongs to the people and not to the officers.” She was proud that old ex-slaves were helping one another locally. She also was excited that ex-slaves were exercising their citizenship rights to gain a new law at a time when disenfranchisement had closed other avenues for political action. The association was off to a promising start.42