CHAPTER 4

Voices of the Ex-Slaves

To render assistance to its members in good standing and to devise ways and means for the caring and establishment of decrepit ex-slaves, their widows and orphans, and to unite all friends in securing pension legislation in favor of the ex-slaves.

CHARTER OF NEW ORLEANS CHAPTER

(JUNE 1899)

THE LOCAL COLUMBIA, Boone County, Missouri, National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association Lodge Number 4 convened its monthly meeting in the basement of Wheeler Chapel Church one evening in the fall of 1899. Luvenia Fields, the secretary for “the insuing year,” carefully took the minutes, and she also read aloud materials sent by the association headquarters to her husband, Reuben, and other members, some of whom could not read or write. The oldest member present was 101 years old; the youngest, thirty-nine.1

It was a sadly impoverished group that the federal government had declared war on: small sects like those at the Boone County meeting. But the power of the idea of reparations and the growing number of supporters scared government officials, even though they had the groups under surveillance and knew that they were nothing more than ex-slaves and their families meeting to commiserate and work peaceably to achieve economic justice.

The Boone County, Columbia, Missouri, Lodge was one of many branches and very typical of the groups Mrs. House and Dickerson had organized. The Association had continued to grow like wildfire after the 1898 convention. Mrs. House and Dickerson had enrolled at least 34,000 members by the middle of 1899 and thousands thereafter. Local association affiliates were organized in Atlanta, New Orleans, Vicksburg, Kansas City, and small rural and urban communities all across the South and Midwest. Like the veterans’ pension lobbyists and land agents and Vaughan’s example, they started a newspaper, the National Industrial Advocate. The paper’s name reflected the ex-slaves’ workers’ consciousness in a period when attempts by blacks in some communities to demand pay for their work had led to violence.2

As they recruited members, Mrs. House and Dickerson distributed literature, arranged annual national meetings, collected petitions from ex-slaves, and supported lobbyists in Washington for the passage of pension bills. Along the way they also strongly emphasized the need for local mutual benefit activities as the linchpin of their solidarity. Membership, open to all ex-slaves and anyone who wanted to support the cause, required the payment of an initial fee of twenty-five cents and then ten cents’ monthly dues. Local organizations paid $2.50 for a charter. The association’s rules also permitted the possibility of “extraordinary” collections of five cents per member to defray unusual expenses. House traveled extensively even after they had identified agents among the preachers in communities to mobilize for the association. She spoke at public meetings constantly “to both white and black” people about the cause. Besides local ministers, Mrs. House and Dickerson recruited other leaders as agents of the national organization in the field to collect petitions and keep the membership informed.3

House’s travels took her to all of the ex-slave states, including those on the border. She went to Kansas, to which ex-slaves had migrated as part of the 1879 exodus and to Oklahoma, where African Americans had developed black towns. Statewide chapters incorporated, and branches and lodges grew everywhere she went. At meetings like the one on that September evening in Columbia, Boone County, Missouri, where Luvenia and Reuben Fields and others met in a church basement, members told sad stories that were so much like Mrs. House’s own personal history. In the telling and retelling of their slavery, hard work, poverty, and the condition of their relatives, neighbors, and friends, association members reinforced the commitment that kept the organization together and growing.

Everywhere Mrs. House went, the story was familiar. Boone County’s ex-slaves lived among a population about the size of Callie House’s birthplace in Rutherford County, Tennessee. The county lay in the middle of the state of Missouri, at the confluence of the nation’s mightiest rivers, the Missouri, the Ohio, and the Mississippi. Its topography includes gentle prairies, water-fed plains, and Ozark uplands. Boone County farmers raised livestock and corn, oats, wheat, rye, barley, tobacco, and fruit. The county had few large slave owners; only 13 percent of slaveholders owned more than ten slaves and only 1 percent had more than twenty. On even the large plantations, the staple crop for-profit system of the South remained largely unknown. Slaves did general farmwork for farmers who raised diversified crops. Many of the male ex-slaves who joined the association continued as farm laborers, and the women worked as laundresses and domestic servants. Most of them were dark-skinned, heavyset, and of medium height, and Callie House resembled most of the other women at this meeting and others. She often visited local councils like this one during what she described as her travels “among strangers,” organizing for the cause.4

Ex-slaves at the lodge meetings talked of how far they had come since slavery and yet in recent years they had a sense of skidding backward to destitution. Some had stories of harsh masters and slave patrols. They talked of how their actions were controlled by their masters and limited by the slave codes, and the risks they were willing to take to exercise some freedom. Almost everyone at the meetings had been part of trying to develop community with other slaves and had been whipped for their trouble. They had slipped away to dance with slaves at another plantation or chatted among themselves on market days or during trips to town or gathered to have prayer meetings despite the ban against having a religious meeting without a white person present.5

The ex-slaves had almost uniform recollections of constant deprivation. They talked of wearing clothes until they were worn out and going barefoot even in winter. Food consisted of an unvarying routine of water and cornmeal either fried into hoecake or boiled into grits. Even for slaves owned by wealthy whites who had smokehouses bulging with meat, meals did not vary much. Some ate buttermilk with cornbread crumbled into it. Less stingy owners permitted slaves to have biscuits made from “shorts” on Sundays, the “stuff dat they feed cows,” and sorghum, a syrup made from grass. At Christmas, which “meant no more to us dan any other day,” some were given sorghum and shorts to make gingersnaps.6

Beyond the poverty and persistent entrapment, the deepest wounds persisted from seeing other slaves sold away and families torn asunder. Done for whatever purpose, the separation of families was a painful memory for every ex-slave. They talked of mothers taken from their babies and being whipped for crying out in their pain. Some remembered being separated from their parents even when they had forgotten almost everything else about the slave experience. There was H. Wheeler, a local slave owner, who had sold his slaves so he could go to join the California gold rush. He had sold thirty-year-old Milly and her children and three other youngsters, all under ten years of age. At the sale of H. B. Hulett’s estate in 1858, one buyer bought Henry, Caroline, and her two-year-old daughter. Three years later to settle business debts the family was sold again. John Bruton’s widow inherited three men and two women. The remaining heirs divided up the ten children among his slaves, ranging in ages from two to ten years. Sometimes one member of the family would be manumitted but not others. William Jewell provided for the emancipation of a mother but not her children. John Tuttle freed George and left his wife the right to emancipate any slave. When she died, she freed George’s wife, Eliza, but none of their children.7

The ex-slaves told of constantly praying and of hearing secret prayers for freedom all of their lives in bondage. They saw the coming of the Civil War as answering their prayers. Missouri was the state where the Compromise of 1820 had been a catalyst for fights over slavery along geographical divisions and the Dred Scott case, which reinforced slavery. The state’s people, economy, and political interests had long been divided along sectional lines. Antislavery and foreign-born immigrants in St. Louis had defeated attempts to secede from the Union. But in the border states like Delaware, Maryland, and Kentucky slavery remained even though they did not join the Confederacy. In 1860, there were 5,034 slaves, 53 free Negroes, and 14,399 white citizens in Boone County, Missouri.8

Some owners took their slaves farther south, hoping to keep them in servitude. Some blacks ran away to free territory; others followed the Union troops that passed through; and some joined the Union Army. Those who stayed behind heard about what happened to some who left. Seven men who ran away in 1863 enlisted in a regiment of Massachusetts troops and were sent to Morris Island, South Carolina; within six months only one survived. In Boone County so many slaves ran away that their flight became an exodus. In the whole state there were 114,931 slaves in 1860 but only 73,811 in 1863. In Boone County the numbers of slaves decreased from 5,034 to 2,265 between 1860 and 1864. Lincoln’s Civil War policy included the payment of compensation to owners who freed their slaves for service in the border slave states, including Missouri. Slavery was abolished by the state legislature in January 1865.9

The ex-slaves in the association had vivid memories of the joy of emancipation and the confusion in its aftermath. Missouri was in chaos throughout the war and calm was not easily restored. Although the Union maintained political control, it had to endure several skirmishes and battles between U.S. soldiers and troops organized by the governor, Claiborne Fox Jackson, a secessionist, and Sterling Price, whom the governor appointed as commander of the pro-Southern militia. The state became a no-man’s-land of hit-and-run raids, arson, ambushes, and murder. Confederate guerrillas became notorious “bushwhackers.” Their followers after the war were people like the outlaws Jesse and Frank James and Cole and Jim Younger. The guerrillas tended to be sons of farmers or planters of Southern heritage, three times more likely to own slaves, and with twice as much wealth as the average Missourian. On the Union side, “jayhawker” counterinsurgency forces from Kansas matched the bushwhackers with similar tactics. In addition, Price, who retreated to the southwest corner of the state, continued to harass soldiers while claiming and losing territory during the war.10

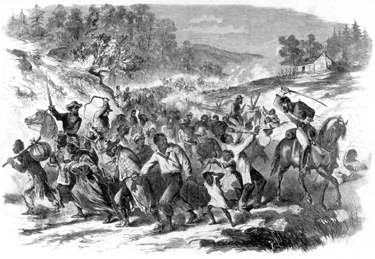

“Negroes Driven South by the Rebel Officers,” Harper’s Weekly, November 8,1862. Slaves were driven to the deep South in the hope of keeping them in bondage. Some slaves ran away to free territory, others followed the Union troops who passed through, and some joined the Union Army.

The ex-slaves in the association told of the danger and constant uncertainty of the guerrilla warfare and the risks run by those who had run away. Some masters tried to avoid trouble by treating any soldiers or guerrillas who showed up, whether rebels or “blue jakets,” with equal hospitality.11

The ex-slaves remembered how soldiers and guerrillas would suddenly appear, looking for food. They would pick apples from the orchards, raid smokehouses and granaries, and make the slaves kill and cook chickens for them. The owners would warn the slave children not to go off with the soldiers because marauders would sell them south, never to return again.12

The ex-slaves recalled that the bushwhackers had shot and killed two Boone County blacks working near the village of Stonesport. They also had to be wary of guerrillas who pretended to be Union soldiers, whom the slaves saw as bringing freedom. For example, a woman who had fled her slave master and established herself near Sturgeon went back to bring another woman and four children to live with her. Bushwhackers disguised in federal uniforms shot and killed all of them except two small children. Slaves and masters were caught between a rock and a hard place. If they helped bushwhackers, the Union Army would harass them and if they helped the “blue jakets,” the bushwhackers would terrorize them.13

Even after January 1865, when slavery officially ended, the danger persisted. Ex-slaves told of the confusion and violence. The Jim Jackson gang of bushwhackers, several of whom were Boone County residents, terrorized the area’s blacks. In February 1865, the gang posted a notice saying that freedpeople must leave the county by February 15 or be killed. They also warned that any farmers who hired the freedpeople would be killed. When the deadline passed, the bushwhackers murdered a freedman working for his former master. They also hanged two blacks and threatened the white man who had hired them. Such terrorism continued in the county until bushwhackers were suppressed by the Union military in June 1865.14

The ex-slaves bitterly described how their poverty and deprivation worsened immediately after emancipation. Within two months of the Missouri legislature’s antislavery ordinance of January 1865, more than thirty men, women, and children died. On some days as many as three burials took place. The ex-slaves lacked food, fuel, and homes. They recalled that when they had been told they were free, it was hard to figure out what to do. Some owners asked them to stay but would not pay them. Some hired themselves out for food and clothing. Others left to try to find their mothers and fathers, searching the faces of any African Americans they met to see if they saw a resemblance. Others whose fathers and mothers were on the same farm told of how the families lived practically out of doors until they could build a log cabin. Others traveled around doing whatever work they could find. Some remembered being disappointed because they thought the slave owners’ farms would be divided and land given to them. Some ex-slaves recalled how their masters had “turned them out of doors,” to walk down the road in January 1865 in the snow. They were so angry at them for being free that they got rid of them as quickly as possible. Others had tried to keep the slaves in bondage, claiming their children as apprentices. Some exslaves had to leave secretly in the night because their masters were watching and would not let them leave in the daylight hours.15

The ex-slaves rejoiced when brighter days seemed to appear on the horizon. Whatever anger they had about emancipation, whites needed workers and signed labor contracts with the freedpeople. Freedpeople could work and get paid. George Jacob, following the usual local pattern, hired two women for $5 a week to do general housework and yard work. He also hired a black man to work his plantation for $12.50 per month. Businesses that had hired slaves from their masters now hired and paid the slaves. Christian College paid men $15 to $20 per month and women $8 to $10 to work as cooks, janitors, or fire lighters or to run the laundry. Those African Americans who had trades worked as blacksmiths or painters. Most of the men in the Boone County chapter took jobs as farm laborers; the women worked as laundresses and domestics.16

The Boone County ex-slaves’ lives improved in the next few years after Emancipation, when the community quickly regrouped, as African Americans did throughout the slave states. They sought to pool their resources and work together. The free Negroes who had managed to gain their freedom before the Civil War provided the only economic base in Boone County afterward. There were fifty-three free blacks in the county in 1860, only twelve of whom owned property. Their total personal estate was worth $5,220, including the property of Cinthia Boyce, a washerwoman who had $100. Gilbert Akers, the largest landowner, bought his freedom, then purchased some town lots, which he resold. By 1864, he had enough money to buy his fourteen children and grandchildren. By 1880, the Census identified blacks as making up 18.4 percent of the county population; their occupation was farming, as owners, renters, or sharecroppers. The largest landowners were persons who had been free before the war. However, some of the ex-slaves had been able to make a living as farmers since emancipation.

The Boone County ex-slaves recalled with pride the glorious day when they had achieved a major goal: to have their own churches where they could worship freely and listen to their own preachers. Another sign of their progress in freedom could be seen in marriage data. After slavery the Missouri legislature made marriage mandatory for former slaves living as husband and wife. Three hundred marriages took place in Boone County between 1865 and 1866, most of which were performed by white ministers. There were only two black preachers in the county at first, the former slaves Henry Warfield and Armstead Estes, an African Methodist Episcopal Church minister, who began to perform marriages. By 1890, almost all marriages among blacks were conducted by African-American ministers, one sign of the growth of the black church and clergy.

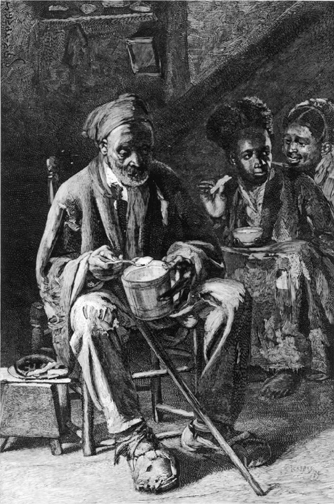

These impoverished freedpeople’s diet consists of cooked corn cake crumbled in soured “clabbered” milk. “Hoecake and Clabber,” Harper’s Weekly, November 10, 1885.

Boone County African Americans made churches their most important community political, religious, and social institutions, and many of Mrs. House’s meetings were held on church property. Most of the ex-slaves who attended church were either Baptists or Methodists. At first black churches met in homes until they were able to afford houses of worship. St. Paul’s African Methodist Episcopal Church in Columbia, which had 206 members in 1900, had become the largest black Methodist church in the county. Second Baptist Church, founded in July 1866, had sixteen original members, with James Hudson, licensed by the local white Columbia Baptist Church, as the minister. With a $3,000 loan in 1894 from the pianist and successful entertainer “Blind Boone,” the congregation completed a new brick church. John William “Blind” Boone became the most famous local black of the period. Boone, along with his manager, John Lang, Jr., traveled throughout the country exhibiting his extraordinary talent as a pianist; he could make the piano simulate violins, guitars, banjos, and tambourines. Boone was a great resource for the community and occasionally gave concerts specifically to help the poor. By the time the association was founded, about 23 percent of the 4,500 local blacks belonged to churches. The Baptists were the largest denomination, followed closely by the Methodists. Black churchgoers raised funds from cakewalks and picnics and even solicited contributions from white coreligionists.

When interested blacks organized in the Boone County Lodge of the Ex-Slave Association, they already had experiences with fraternal and benevolent societies in the county. These organizations fulfilled a need for social activity, provided relief for members in need, and acted as burial associations and insurance companies for members. In 1867, blacks established the First African Benevolent Society of Columbia to aid the infirm, destitute, and aged. Membership cost a $2 initiation fee and monthly dues of fifty cents. By June 1867, there were fifty-seven members. By 1869, the Masons organized a lodge, and in 1879, the United Brothers of Friendship was organized. Both provided burial benefits for members and some monetary assistance for families when a member died. The members of both fraternal groups were generally under fifty and in their prime working years. Sanford Estes, a laborer and preacher who joined the Ex-Slave Association lodge, was a member of both the United Brothers of Friendship and the Masonic Lodge.

The children of Ex-Slave Association members had some literacy, primarily because African Americans in the county founded schools. In the summer of 1865, a committee of African-American church members held a mass meeting to raise funds for a church and school dual-purpose building. They raised $149 and bought a lot for $20; the Baptists then pulled out and started their own school. In 1867, St. Paul’s A.M.E. Church asked the state legislature for funds to support their school, but, instead, the legislature gave funds to the Baptist church and school. Consequently, by 1867 there were two schools in churches led by black men. The Baptist school, conducted by Charles Cummings, continued to receive state funding and was named the public school for blacks in 1868. Funds from the state, the community dinners, picnics, festivals, and the Freedmen’s Bureau made it possible to erect a building, known as Cummings School until 1898, when, upon a petition by African Americans, the Columbia School Board renamed it Frederick Douglass Academy. By 1898, the school had begun a high school program.

Between 1875 and 1900, education was not ideal for either African Americans or whites; however, blacks’ schools had worse conditions. The black schools were overcrowded, and the teachers were paid less than the white teachers. Missouri’s schools were segregated by law in 1889, but segregated education had always existed in Boone County. In 1900, only 14 percent of the black population over age sixty was literate, as were 19 percent of those fifty-one to sixty, 34.6 percent of those forty-one to fifty, and 50.8 percent of those thirty-one to forty. However, 71 percent of those between twenty-one and thirty were literate. Most of the ex-slaves in the local branch of the association were illiterate, but most of their children and grandchildren could read and write.17

Gains notwithstanding, the old ex-slaves at the lodge meeting talked about their despair in recent years as the meager gains they had made since Emancipation had stagnated or evaporated in the 1890s. They not only suffered from the same poverty and discrimination experienced by blacks elsewhere, but they endured the same class divisions within the community. Their circumstances made them good candidates for Cal-lie House’s organizing efforts.

From the members, she heard how the county’s always-present racial tension seemed to worsen. Ex-slaves recalled how a group of white men had shot into the African Methodist Episcopal Church during a festival in 1868. In 1878, a white man had shot a black cook for not preparing his breakfast quickly enough. In 1894, when a Boone County black woman ignored the vulgar remarks of a white man, he shot her. He was jailed, but not before he shot a black man. At least two riots occurred, one in 1878 in Ashland and another in 1882 in Rocheport, both with overly liquored participants, black and white, involved. In the second riot, six black men were jailed for two to seven years for shooting into a crowd of white men, injuring some after an intoxicated black man insulted a white man who drew his pistol and knocked him down. In 1895, Willie Eaton, the sister of one of the rioters, shot and killed Thomas J. White, the marshal responsible for arresting the black men. Convicted of manslaughter, she received a two-year sentence after a change of venue to Jefferson City. Clearly, African Americans in the county were prepared to try to protect themselves.18

After the enactment of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, male ex-slaves could legally vote. However, not all of the exslaves understood how voting would improve their lives since elected officials ignored their black people’s pleas. In 1896, the year they organized the association lodge, Columbia blacks protested a legal decision directing four black women arrested as prostitutes to work on the city streets and a rock pile. Black citizens, led by Reverend R. L. Beal of the A.M.E. Church, opposed prostitution but thought this was an extreme punishment. They publicly asked the city council to eliminate the practice, but the council refused, replying that it needed to rid the city of disreputable women.

In the ex-slaves view, the relatively small amount of progress freedpeople had made by the late 1890s had come to a halt. The depressed agriculture of the country took a toll. Many blacks who owned land lost it. By the 1900 Census, only 69 percent of blacks who farmed in 1880 were still doing so. African-American property ownership and taxpaying declined. Whites controlled blacks through segregation, lynchings, and a vagrancy law that provided for “selling away” anyone adjudged a vagrant by the local court for four years to an employer to work out his term. The law made no distinction based on race but targeted blacks.

For Boone County ex-slaves, their troubles had made it difficult to gather the resources to function after they organized the lodge. The national agricultural depression affected all Missourians but hit African Americans especially hard. They had become poorer in recent years, when in the 1880s they had thought they were just beginning to prosper. Increasingly after the Civil War black wives had to work, though, emulating the pattern of whites, the freedmen wanted to have their wives remain at home. Between 1870 and 1900, the number of households with only one worker decreased and the number of families with two or three workers grew. Also, relatives moved in together, so that nonnuclear households grew by 1900. In 1870, most wives did not work and only three women in the county worked as laundresses and one as a seamstress. In 1880, 129 worked as washerwomen and 3 as seamstresses. In 1900, 187 women washed clothes and 13 made a living sewing.

In 1900, Boone County had 39 African-American professionals: 13 ministers, 22 teachers, 2 physicians, 1 lawyer, and 1 musician. In Columbia, blacks owned one blacksmith shop, one barbershop, one grocery store, and a lunchroom. However, most African-American men worked as unskilled laborers earning seventy-five cents to a dollar a day. The women worked mostly as washerwomen, earning a weekly income of two to three dollars. Their economic status was only slightly improved since 1870, five years after Emancipation. In 1900, 186 black farmers operated 178 of the county’s farms, only 5 percent of the total. The farms were mostly small landholdings of which blacks owned 52.8 percent. The largest African-American taxpayers, except for “Blind Boone,” had lived in the county and had been free before the war. Even when blacks owned their homes, they were mostly mortgaged; but most owned no property at all. The city council enacted a poll tax of one dollar for every male citizen between twenty-one and fifty in 1895. These taxpayers numbered 812, and 31.2 percent of them paid no other tax. Among those assessed, 30.7 percent were black; of these, 225 paid no other tax or were delinquent in payment of their real and personal taxes. They were 88.5 percent of those paying a poll tax and were delinquent in other city tax payments. Less than 50 percent of those assessed paid the tax, and it was repealed two years later. The poor obviously had no resources with which to pay.19

Occasionally some African-American veteran or widow succeeded in obtaining a military pension, which became big news. Peter Hadan, a blacksmith, received a pension of $6 a month beginning in October 1885 for his injuries during the war. In 1880, Dorcas Williams, a fifty-year-old woman, received $2,074 in past due benefits. Her slave husband had been killed in the war in 1864. She was owed $8 a month since that date and $2 per month since 1866 for each of her four children. She would receive the pension until her children came of age or until her death. Insurance benefits payable at death also relieved pressure for some.

The economic distress in Columbia at the time the Ex-Slave Association was founded stemmed from many causes. Columbia failed to obtain a mainline railroad, which lowered land prices already depressed by agricultural depression. The steamboat declined as a result of competition with the railroads, and the river towns of Boone County lost their importance. Population losses abounded in the county. Everyone suffered, but African Americans suffered worse. The university, where some blacks worked as janitors and maids, remained a stable employer, but for only a small number of workers. Ironically, as literacy increased among blacks, the number and percentage of laborers and domestic servants increased. By 1897, most African Americans were either servants and laborers for white citizens or professionals serving their own community.

The world has changed for master and slave. “Old Master and Old Man, a New Year’s Talk over Old Years Gone,” Harper’s Weekly, January 11, 1890.

The ex-slaves lamented that because of their poverty, after the lodge was founded, dues payments were often hard to come by. Their carefully kept ledgers showed that some members paid in installments of five cents until they reached the requirement of twenty-five cents and ten cents for local dues. Most of the members were elderly. Henry Clay, born in Kentucky, had been the slave of Jefferson Garth, a prominent Boone County slave owner. Clay was seventy-nine and his wife, July, was sixty-eight. Auderine Wills, age seventy-four, had been born into slavery in Winchester, Kentucky, while Joseph Gosling had been the slave of local slaveholder Sylvester Gosling in Columbia. Squire Smith, who was sixty, worked on a farm. His wife was fifty-four; they had four children, three of whom were grown and the youngest of whom was sixteen. His two sons also worked on the farm. Allen Woods, who was fifty-nine, also did farmwork. His wife was fifty and his four children—three girls and a boy—were all grown; the youngest, a boy, was seventeen. Edward Lawson did farmwork. He was fifty-four, his wife was thirty, and four of his children—two boys and two girls—were grown; his youngest son was seventeen. Sandy Turner was a farmer. He was seventy-two; his wife, Harriet, was fifty-six and his five children, two boys and three girls, were grown. The youngest, Phoebe, was eighteen. Scott Brashears and his wife, Amanda, both in their sixties, lived with their grandson Oliver Woods, born in 1892, and granddaughter Lil-lie Eaton, born in 1896.20

Squire Smith, Boone County ex-slave. Squire Smith was a member of the Ex-Slave Association.

Unidentified Boone County ex-slave. African Americans like this man joined the Ex-Slave Association.

Missouri ex-slaves Richard and Drucilla Martin. Many of the ex-slaves who joined the movement were poor, and many tried to work although they were old and frail.

The ex-slaves were so poor that many of the old and infirm continued to work. Creasy Mack, who was about eighty and widowed, still did live-in household work for her employer, Jake Straun, a merchant. Despite their hardships, the local branch of the association was very important to the members. At the May 3, 1897, meeting, they planned to host a state convention on April 20 and set aside $5 to pay for the rent of Wheeler Chapel, “above and [below] the basement for 5.00 day and night.”21

At one meeting only five people showed up, but by the end of 1899, the association was on its way with 125 members and enough funds to pay the fifty cents’ rent for each meeting in the church basement. It could also begin amassing a “treasure” for the local mutual benefit, medical care, and burial assistance for the members. It had also collected dozens of petitions and sent them off to headquarters. This was at a time when the entire black population of Boone County consisted of just about 4,500 people in the rural areas and surrounding towns, including Columbia. At this point only about 21 percent of the black population nationally had been born into slavery. In Boone County, only 676 persons were thirty-one years old or above and therefore could have been born in slavery and eligible for a pension. The membership of the lodge consisted of at least 20 percent of those African Americans who were eligible for a pension. With Callie House’s encouragement, the Boone County lodge continued to send in petitions to the national office and to provide what relief they could to impoverished members.22

“Rent Day,” Harper’s Weekly, April 28, 1888. Many ex-slaves had miserable housing and few resources to pay for it. When they could work, the wages were too low. This old couple mull over whether they have enough to pay the rent collector.

Although blacks’ struggles were similar across the country and House encountered similar concerns everywhere she went, each community had its unique qualities and situations. The ex-slaves in New Orleans, for instance, lived in a community that had long had a sizable free Negro population and where Reconstruction had come early, but their post-Emancipation poverty differed little from that of the freedpeople in Boone County. When Mrs. House traveled to New Orleans in September 1899 to visit the local association council, she touched base with and provided inspiration to the members. She stayed in the home of a member, Lillie Brown, on Basin Street. While in the city, she spent hours with the local members collecting petitions and listening to their stories of slavery and the days since emancipation. They told her of their problems making ends meet, exacerbated by economic depression against the backdrop of the worsening inequality in that city and state. Racial turmoil erupted repeatedly among workingmen on the docks. In 1890, Louisiana legislators enacted bills to forbid equal accommodations on railroads and other conveyances. New Orleans’ African Americans persistently agitated against segregation in the 1890s, although they repeatedly lost. In 1895, the Catholic Church announced the segregation of all services. Plessy v. Ferguson, in 1896, closed the final curtain. In 1898, the state took away African Americans’ right to vote. At a state constitutional convention, delegates laid down the legal blueprint for white supremacy. The chair of the Judiciary Committee declared, “Our mission was to establish the supremacy of the white race.” More than 120,000 African-American men were disenfranchised, and the Louisiana Democratic Party declared itself a whites-only organization.23

None of the ex-slave council charter members’ relatives had joined local African-American men who had gone to Cuba, serving in one of four African-American “immune” regiments, as a result of the Spanish-American War. However, they described how the entire African-American community was upset at the insult, embarrassment, and unequal treatment the black soldiers suffered in the service. The troops were organized because, during the war, Washington officials from President McKinley on down had an almost superstitious dread of Cuba’s yellow fever and malaria. Secretary of War Russel Alger advanced the idea that those who had come from semitropical or tropical climates had probably had the disease and were immune to it. Many of the soldiers became ill and some died, but the remainder spent their time as an occupying force engaged in guard and patrol duty.24

Many of the New Orleans council members, like those in Boone County and elsewhere, were old and experiencing great difficulties doing the manual labor that had always been their only occupation. Further adding to their problems, the economy remained depressed, which reduced employment opportunity for the younger generation. The members told House that the harsh conditions they faced made them anxious to join the association. Their chapter was incorporated on June 22, 1899, just a few days after the local African-American soldiers returned from Cuba. There were already a number of mutual aid societies still existing in the city. New Orleans’ African Americans, like those elsewhere, had long organized mutual aid societies. Between 1880 and 1900, nineteen operated in the city, although not at the same time. A quite common way for the poor in a church or other organization to join together for mutual aid in time of illness or death, they developed because of habit and poverty. The local Ex-Slave Association’s chapter had a somewhat different focus: “to devise ways and means for the caring and establishment of decrepit ex-slaves, their widows and orphans” and “to unite the efforts of all friends in securing pension legislation in favor of the ex-slaves, particularly by petitioning Congress” to pass the pension legislation reintroduced by Senator Mason. In working to gain pensions, they would “work under the advice and guidance of and cooperate with the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association of the United States of America.”25

They engaged pension notary Louis Martinet to prepare and record their charter. He had been a major player in the progress of and reaction against people of color that had taken place in the city. He was a member of the class of the more educated African Americans who had executed the anti-Jim Crow litigation. A widely respected Afro-Creole lawyer, Martinet and other African-American graduates of Straight University Law School became organizers of a citizens’ committee to attack the law that segregated transportation in the city. They organized one test case in which the local court defeated their efforts by releasing Daniel Desdunes after local police arrested him for violating the law on a city streetcar. They chose Homer Plessy next and succeeded in having him arrested and charged for refusing to vacate his seat on a passenger train. Martinet decided to ask Albion Tourgee to represent the cause. He explained that local black lawyers mainly practiced in police court. He also wanted an experienced appellate lawyer to take the case all the way to the Supreme Court. Martinet, who organized the effort, developed the litigation strategy, and picked the lawyers, remained a hero to the African-American community despite the eventual loss of Plessy v. Ferguson in the Supreme Court.26

The eight incorporators of the New Orleans Ex-Slave Association chapter included six men and two women. The participation of one of the women, Lottie L. Boyd, wife of Henry Boyd, as a married woman, required his personal authorization. The other woman, Lillie J. Bell, was single. They named as original officers Frederick S. Diamond, president; “Mistress” Lea Cavender, vice president; James T. Jones, manager; George A. Green, secretary; Lillie J. Bell, assistant secretary; William D. Brown, chaplain; Phillip S. Burton, lecturer; and Ervard (Edward) Barnes, inspector. Samuel A. Jackson was the other charter member. George A. Green served on the executive committee of the national organization. The founders set a convention of delegates to elect officers on the second Monday of August 1902. In the interim the board would manage the affairs and the founding officers would represent the association. Lottie L. Boyd, Henry Boyd, and Marcellin Zephilin, because of their illiteracy, signed with an X.27

Marcellin Zephilin’s story, so similar to many House had heard, explained why even Civil War veterans eagerly joined the pension movement. Born a slave of Alexandre Mouton, of French origin but Arcadian “Cajun, not Creole,” on the Ile Copal Plantation in Vermillionville, Lafayette, a prairie and bayou sugarcane region, he said he did not know why his master had named him Marcellin Zephilin. Mouton held Zephilin’s father, Tom, and mother, Jennie, among the slaves on his plantation. Mouton, a Jacksonian Democrat, served in the legislature as a U.S. senator and as governor of Louisiana after his election to a term beginning in January 1843. He retired to life as a sugar planter and railroad promoter and then led a delegation to the Democratic National Convention in 1860 and chaired the Louisiana secession convention. During the war, when Union troops captured his plantation and used it as a headquarters, he had to flee. They burned the sugar mill and other works buildings and freed his 120 slaves, including Marcellin Zephilin.28

General Nathaniel Banks’s Corps d’Afrique swept him up, along with thousands of other freedmen, into the Union Army, recording his enlistment at five feet, seven inches, black hair, black complexion, and brown eyes, at the Touro Building in New Orleans in May 1863. He served in the 97th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. Colored Troops until the end of the war. Wounded by a gunshot in the left leg below the knee at Fort Blakeley and hospitalized at Mobile, he also suffered a partial hearing loss. After his discharge he took the name of his slave father, Tom Jones, instead of Zephilin. He became a Primitive Baptist minister under the name Tom Jones, but when he applied for a pension the Bureau denied his claim. They found no Tom Jones on the rolls of the 97th U.S. Colored Troops.

Mrs. House knew from her own experience, and from what she heard everywhere she traveled, that many African-American soldiers and their widows had similar difficulties because they lacked documents to prove their names or dates of birth. He then filed as Zephilin and was at first rebuffed. After his continued complaints and a long investigation, he finally received a pension. However, the bureau agent told him he must call himself Zephilin and not Jones. He continued to identify himself as Jones except when dealing with the government and answered to both names. Sometimes others hearing his name spelled it Dephilin or Zephirin. By the time he responded to House’s plea to organize and helped to charter the Ex-Slave Association, Jones had developed rheumatism, asthma, and shortness of breath and could no longer preach or perform manual labor. He had come to rely on his pension and friends and family for his livelihood.29

But his anger was reinforced when he applied for an increase in his pension under a provision covering veterans who reached age seventy-five and the bureau rejected him again. He could not prove his age. The bureau first asked why he did not simply submit his birth certificate or family Bible entry, which he, of course, had never had. When he obtained an affidavit from a grandson of his former owner, bureau officials refused to accept its validity since it reflected only his recollection. Widows and veterans who experienced such harassment from the Pension Bureau were naturally inclined to seek relief by joining the ex-slave pension movement.30

During House’s travels, what she saw and heard from the old ex-slaves strengthened her commitment to the movement. However, the growth of the association had attracted the attention of the Pension Bureau. While she was still reveling in the progress of the chapters, the government was accelerating its attack on the association. She was successfully doing the work the members had elected her to do. But her resolve would be sorely tested.