CHAPTER 5

The Movement

Fights Back

My face is black is true but its not my fault but I love my name and my honesty in dealing with my fellow man.

CALLIE HOUSE

(1899)

CALLIE HOUSE had a major problem after the Post Office Department denied the Association the use of the mails. The pension movement workers were left with Wells Fargo, Adams, or American Express to distribute materials. However, having to use commercial delivery services and to travel more often to keep in touch took time and the Association’s scarce resources. Mrs. House needed to provide the inspiration that would keep agents organizing and collecting petitions, and local chapters providing mutual assistance to their members. She had to do this in the wake of ongoing federal harassment, and avoid permitting the harassment from becoming a major distraction from the Association’s real work. Mrs. House remained optimistic and the work continued so successfully that soon their press critics complained that the association had branches “in almost every little hamlet and village throughout the south.”1

When Mrs. House received the September 1899 notice of the fraud order from Barrett, she had no idea how committed the federal officials were to stopping her and the movement. Responding as if she had some citizenship rights the federal government was required to respect, Mrs. House made no apologies for her work. She provided a detailed explanation of the movement’s mission and actions. This, she thought, would allay Barrett’s concerns. She explained, “1st we are organizing ourselves together as a race of people who feels that they have been wronged.” She rejected his charge that they had misled members. On the contrary,

We tell them we don’t know whether they will ever get anything or not but there is something due them and if they are willing to risk their money in defraying the expenses of getting up the petition to Congress they are at liberty to do so.2

Her explanation, in keeping with her education in civics in Rutherford County’s primary schools, insisted that “the Constitution of the United States grants to citizens the privilege of peaceably assembling themselves together and petition their grievance.” Objecting to the government’s disrespect of the movement, she continued that African Americans had

a perfect right as ex-slaves to gather and organize ourselves and elect men and women to organize our race together to petition the government for a compensation to alleviate our old decrepit men and women who are bent up with rheumatism from the exposure they undergone [underwent] in the dark days of slavery.

Furthermore, Callie House told Barrett:

Common horse sence [sic] will teach anybody that the officers of this organization are powerless to get a pension from the government for each ex-slave for 25 cts when ever there is no law on the statute books to pension them.

Proudly, she told him “My whole soul and body are for this-slave movement and are [am] willing to sacrifices [sacrifice] for it.”3

Callie House’s forceful and coherent response to Barrett angered federal officials. They also began to understand that she was the de facto head of the Association. From that day on, intent on breaking the ex-slave movement, postal officials focused on throttling her to silence. Nashville postmaster A. Wills explained to Acting Assistant Attorney General Barrett, “She is defiant in her actions, and seems to think that the negroes have the right to do what they please in this country.”4

After the post office issued the fraud order on October 2, 1899, Postmaster Wills told headquarters that he had delivered the letters to Reverend H. Smith, the national secretary in Bransford, Tennessee, in addition to Callie House in New Orleans, through that city’s postmaster. He also quickly disseminated it to newspapers all over the South, asking that they publish it immediately. He stopped twenty-two money orders amounting in total to $53.84 sent to the Association and had them returned to the senders.5

House and the Association continued to organize while attending to the federal surveillance. She traveled more than ever, “lecturing to both white and colored people on this movement.” This was a distinct hardship. Her brother and his wife, who lived next door, helped to care for her children; the oldest, Thomas, was fifteen and the youngest, Annie, was six. Mrs. House had worked all of her life but as a washerwoman and seamstress; this was the work that most black women with children did. But widowed and now working outside the home, Mrs. House had departed from the usual role.

When House traveled to meet with members or prospective members, she encouraged them to believe that pension legislation would eventually pass. However, she “always stated clearly and distinctly that the Bill was not a law but we wanted to petition to Congress to pass the Mason bill or some other.” She explained to members and to the government officials that the dues and contributions paid for representatives in Washington “to look after the interest of the movement to work for passage.” McNairy “went sometime in Jan 1899 and remains in Washington till the last of March,” supported by the organization. As far as she knew, he was lobbying aggressively for the bill.6

The Association leaders had difficulty staying in touch with agents and chapters and members of their families. On November 9, 1899, after the issuance of the mail fraud order, Isaiah Dickerson politely wrote to Postmaster Wills, pointing out that since his mail had been stopped two of his children had become ill without his knowledge. He had found out about the order from “a white friend visiting our city.”7

Feeling the pressure of her poor economic circumstances, House was particularly stung by Barrett’s assertion that association officers had used membership money inappropriately for themselves or to hire members of their families. The Association’s board of directors set a salary of $50 a month for Mrs. House, but actual payment depended on whether the organization could afford it. There was no reason not to hire members of her family, but in fact none worked for the Association. Records from the period show that in 1899 and her early years in the ex-slave pension cause, her daughters were still in school and too young to work. When her boys who were teenagers took jobs, they worked as clothes pressers, car cleaners, and other unskilled low-wage occupations completely unrelated to the organization. When her daughters became old enough, they became washerwomen or seamstresses, except for Mattie, who, as an adult, long after House’s involvement in the pension movement, became a teacher. House’s brother, Charles Guy, worked as a laborer and then a packer in a factory. His wife also took in washing. The Census reported their occupations, and the annual City Directory recorded each member of her family at their workplaces.8

Also unaware of the extent of the federal government’s hostility, Dickerson responded to the fraud order, echoing House’s concerns. He told Barrett that he failed to understand why pension legislation should not have the support “of all true American citizens, regardless of politics.” He thought it “very wrong for any attorney to suppress our rights to petition to better our condition in life.” They were legally incorporated by the “grand old state of Tennessee,” which would certainly intervene if “we overstep our bounds.” He questioned why the federal government should take an interest and hoped the order would be rescinded. This round of communication between the association and the government ended with House telling Barrett that she had done this work for two years and she “did not work for what I got out of it but I believe the movement to be right.”9

Not knowing about the statements in the government’s files expressing disinterest in local chapters and mutual-aid work, House tried to direct federal officials’ attention to the branches. She regarded their activities as key to the work of organizing and sustaining the movement. The association gave the Justice Department a list of local agents and addresses so that they could track their work. The government used this information only to help prove that House was acknowledged as an official of the association. They ignored the proof that the association was more than an empty shell.10

Still not understanding the federal government’s perspective, the association decided to seek revocation of the fraud order against its president, Reverend McNairy, so that he could communicate with the membership and officers as he lobbied in Washington. When their Washington lawyer, William C. Lawson, wrote to the post office asking for the revocation, postal officials refused. On December 9,1899, Barrett responded that since letters and contributions had been sent to McNairy and he took an “active part” in the association’s activities, he would remain subject to the order.11

After newspapers published Barrett’s notice of the fraud order at the Post Office Department’s request, House made herself even more objectionable to Pension Bureau and postal officials. She upbraided him for libeling her across the nation. Readers across the country read that she had fraudulently collected money from “ignorant ex-slave[s], when Barrett had no evidence to support his claims. She wrote to him:

I am an American born woman and was born in the proud old state of Tennessee and I am considered a law abiding citizen of that state anyone that work honestly and earnestly for the upbuilding of their own race would like for it to be recognize that way let it be a white man or white woman are a black man or a black woman.

Although her face was “black,” she valued her good name, and believed in “honesty in dealing with my fellow man,” Mrs. House wrote. Since her election as assistant secretary of the Association, she had worked hard to organize African Americans so they could “render assistance to all members in good standing.” She had also asked Congress to pass the pension bill introduced by Senator Mason or “some measure as good.”12

She reminded Barrett again that the ex-slave pension movement sought simply to exercise their constitutional right to “gather and petition there [their] grievances.” When she lectured to African Americans, she explained the right to petition but “told them it would take some money to defray the expences in getting up the petition or conducting the work.” She had been “honest in my dealing with my fellow man.”13

Immune to criticism, complaints, and pleas for fairness from the ex-slave pension movement, the postal officials assiduously refused to process mail sent to the organization or to House and the other officers individually. Association organizers tried to evade the order by having postal express orders sent from the chapters or by having mail sent through others. They kept lobbying, mobilizing, and obtaining signatures on petitions, despite the obstacles. They also kept up the introduction of bills in Congress. On December 11, 1899, when Senator Edmund Pettus, Democrat of Alabama, reintroduced the legislation, instead of the serene reception experienced in the past a tumult erupted. Senator Jacob Gallinger, Republican of New Hampshire and chairman of the Pensions Committee, hurriedly denounced the idea as fraudulent. Senator William Mason, a Republican from Illinois, explained that he had introduced the bill before and he had received letters saying “it was used for a bad purpose” by swindlers. Senator John Thurston, Republican of Nebraska, who introduced the bill in the Fifty-fourth Congress, said a Confederate veteran had urged him to introduce it but it had been misused. Senator George Hoar, Republican of Maine, thought the bill should at least be treated with respect because of the British discussion of old-age pensions, and if anyone deserved such consideration, certainly “those whose lives were spent in slavery and whose earnings and labor were given for the benefit of others” did also. Senator Gallinger, after reading letters from H. Clay Evans, commissioner of pensions, alleging “the fraudulent nature of the ex-pension organizations,” referred the bill to his Pensions Committee.14

The negative attitude of the Pensions Committee arose from a consultation with the Pension Bureau, which asked Gallinger in January 1900 to issue an adverse report on the legislation. The Bureau requested that the committee dispose of the bill in a way that would advertise to members the “improper purposes” used with the various bills. Ignoring the mutual assistance purposes of the Ex-Slave Association, the Senate committee complied with the Pension Bureau’s request; its report consisted mainly of a letter from H. Clay Evans alleging “the fraudulent nature of the ex-slave pension organizations” but included no evidence or facts to support the conclusion. The committee denounced the ex-slave pension movement as a means to “dupe the colored people” and said the measure was not even “deserving of serious consideration by Congress.” The report concluded that no one should expect the Congress ever to enact pensions for the ex-slaves. This same committee over-looked its own evidence to the contrary, however, that at least 35,710 people had been issued membership certificates by April 17,1899.15

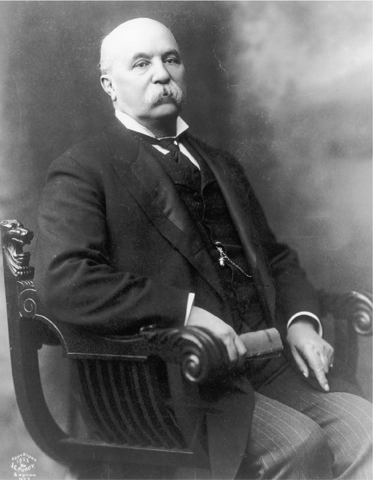

Senator Jacob Gallinger (served 1891-1918), in an effort to stop the petitions and the movement, colluded with the commissioner of pensions to issue a report saying that Congress would never pass a pension bill.

Not knowing of the collusion among the government branches working against the Association and their fear of its successful mobilization, Mrs. House and her colleagues puzzled over why they were facing such racial paternalism and hostility from the Pensions Committee. After all, they did not challenge racial segregation or white supremacy and these fraud concerns had not been raised during earlier pension-seeking efforts. Despite their leaders’ disappointment, they felt that giving up was not an alternative and they decided to continue working. They continued to collect petitions and to hold ExSlave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association conventions. They passed resolutions to send to Congress and state legislatures, and they continued to meet and organize local chapters to provide mutual assistance throughout the South and Midwest.16

While Callie House and the Association struggled against the postal authorities, Edward Cooper’s Washington, D.C., Colored American, on April 21, 1900, summed up the attitude of many well-off African Americans toward the association and the pensions cause:

Despite the widespread warnings of the press both white and colored, there are still some people foolish enough to pay over their hard cash to sundry confidence sharks who run up and down the country pretending that Congress is about to grant pensions to the ex-slaves. No such thing will be done in this or any other generation and whoever asserts to the contrary is a knave, a humbug or worse.17

From Cooper’s perspective, because Congress was unlikely to enact a pension, merely mobilizing to demand legislation constituted fraud.

The government’s effort to suppress the movement continued and accelerated. In April 1900, Callie House received another notice reiterating the broad scope of the fraud order and reminding her that letters sent to individual officers, or to the organization and any postal money orders would be voided as fraudulent. She vented her fury to Barrett, telling him that she wanted to promote “mutual assistance” to members and continue to press Congress to pass pension legislation. She and the other officers had “not promised nothing to nobody.” She denounced the charges as “not true and I believed they are made against us simply because we are negroes and helpless.” To deflect the harassment, House hired a white attorney, H. Perry Stephens of Nashville. At that time sixteen black attorneys had offices in Nashville, but they practiced mainly in the local criminal courts. Further, some African Americans hired white attorneys, knowing how disdainfully white officials and the courts treated blacks.18

Mrs. House felt increasingly isolated and embattled. On April 30,1900, Stephens asked Barrett for a review and revocation of the order, at least as it applied to her as an individual. He told him that she had been traveling on March 28, 1900, when the notice had come saying that she must immediately produce contrary evidence or otherwise another fraud order would be issued, and had not returned to Nashville until April 1. “It worked a great hardship,” especially in case of the “illness of her children,” if she could not receive mail. If the Post Office Department would not revoke the order, he wanted information on how to obtain judicial review.19

Mrs. House was further disappointed when the Post Office Department rejected Stephens’s appeal. Assistant Attorney General James Tyner replied that House had had ample time to make any defenses and could still do so, but no matter what she submitted, the order would remain in force. Further, Stephens needed to understand that “the issuance [of a fraud order] is solely determined by the department and there is no place to appeal.” The courts had left the matter entirely up to the discretion of post office officials. Because taxpayers and citizens had no constitutional right to use the post office, a service provided on terms set by the department, then a denial for any reason raised no due process concerns. Still believing he might change their minds, Stephens submitted association materials and affidavits to the officials, but to no avail. Today, federal agency actions are reviewable in the courts under the Administrative Procedure Act. However, the act was not passed until 1946. If it had been in place in 1899, Callie House and the ExSlave Association could have at least asked for court review of the fraud orders issued against them. In 1899, association officials had no place to seek redress.20

The Post Office Department, at the behest of the Pension Bureau, continued to attack all ex-slave pension groups whether they were suspected swindlers or sincere promoters of the cause. They also made no effort to ascertain whether the Ex-Slave Association officers actually owned property or bank accounts or to determine the costs of their travel and petitioning or in any way to document their accusations. Instead they simply labeled pensions for ex-slaves a hopeless cause and held that anyone who promoted such pensions, by any means, had ulterior motives.

In February, Postmaster Wills in Nashville reminded his superintendents that they should continue to enforce the fraud order. Their focus should be on Callie House and anyone associated with her. On February 26,1901, the Post Office Department charged that House and G. T. Abrams were “carrying on their ex-slave pension swindle” by publishing the National Industrial Advocate to promote the movement. Veteran pensions and other lobbyists routinely published newsletters or newspapers in this period. The post office, continuing its policy of assuming the existence of illegality, issued another fraud order forbidding the delivery of any mail personally addressed to Callie House or to G. T Abrams, manager of the National Industrial Advocate.21

On March 5,1901, J. B. Mullins, who had been elected president of the Ex-Slave Association, decided to try appeasement and deference to gain revocation of the fraud order. In good faith, he naively wrote to the Post Office Department that after President McNairy’s death, he had been unanimously elected president at the Montgomery, Alabama, convention on October 29-30, 1900. He immediately investigated whether any fraud existed. He found “many fraudulent acts of this nature being practiced upon the people by bogus agents who were not connected with the organization in any way.” He assured them that if at the local level “unprincipled officers and agents” had been elected, it was without the knowledge of the association. But the government’s labeling the organization a fraud meant that the “innocent must suffer with the guilty.”22

Mullins described various impostors who had been reported to him and recalled that the organization had previously reported one imposter to the federal government who, he understood, had been arrested. He knew of a swindler who had “gulled” some people in Kentucky by claiming that he had been “appointed to preach McNairy’s funeral and needed money to defray the expenses.” They had tried to find this “so-called minister,” but to no avail. In view of his cooperation, Mullins hoped the department would reconsider the fraud order. The association, he wrote, had many honest agents and “did a lot of good for the poor old decrepit and worn out ex-slaves, who direly needed mutual aid and burial assistance.” He proudly told them that there was “one local association at Greenville, Ala., that buried eleven members last year.” The federal officials ignored his plea.23

On March 15, 1901, Mullins wrote to President McKinley expressing the same concerns as in his earlier letter to the Post Office Department. He cited the right to petition the government and wrote that the members wanted equal rights and equal protection under the laws; however, following the leadership of Booker T. Washington, “they do not ask for social equality.” If he could obtain removal of the fraud order against the association, he would not even complain of “action taken upon” officers, including the dead President McNairy and the living Dickerson and House. Whether justified or not, an order against them should not have been extended to the organization. He asserted that the organization had nearly a million members. “They have always been loyal to the flag of this country and have no idea of revolting. It would be foolish.” He asked, “If the South continues to disfranchise our people and resort to the mob violence instead of giving a right of trial by jury, what will be our position ten years hence?”24

Mullins’s deferential letters had no effect. Having no access to the records now available, he did not know that official suspicion fell on anyone who worked on ex-slave pensions. He also did not understand that it was the Ex-Slave Association’s success that frightened the bureau and not whether House and Dickerson were honest advocates. The postmaster in Nashville “had long suspicioned him” and requested a fraud order to stop Mullins’s mail in the same month as he sent his letters to the bureau and to the president. The federal officials had no interest in burials paid for by the Greenville chapter or any other. Also, they regarded the large number of association members as evidence of the ignorance and susceptibility of African Americans, rather than as an affirmation of the support for the cause. They wanted the old ex-slaves to remain bereft of even the hope of ever receiving any form of reparations from the federal government. For the government to succeed, it had to demonize all pension advocates as venal agitators.25

Reporting on his pursuit of House, Nashville postmaster Wills wrote to George Christiancy, the assistant attorney general of the Post Office Department, bragging that “in order to effectually wipe out the whole thing, I feel justified at times to resorting to extreme measures.” In his office they inspected all mail of African Americans to see if they had any involvement in the ex-slave pension “business” and then withheld it when they could find any “pretext” at all. “These fellows connected with this association are all slick customers.”26

Federal officials who earnestly hoped that local law enforcement would join in the effort to stop the movement, rejoiced at what they regarded as a bit of good news from Wills: he gleefully reported that “the General Manager Dickerson is in jail in Atlanta” and hoped he would implicate Callie House. Dicker-son had appealed but was “simply playing for time in order to pay his fine of $1,000.00 and continue his rascally proceedings.” Wills forwarded to Washington headquarters clippings from the Atlanta Constitution and the Nashville American and Banner, containing inflammatory invective about the case from the local judge, who had said it was “such a succinct history of the life and possible death of I. H. Dickerson, General Manager, and the death of the Association.” Wills thought they should “congratulate” themselves.27

The press clippings claimed that Dickerson had “deluded darkies” in thirty-four states and the Atlanta chapter sued and had him jailed for nonpayment of $800 bail. He allegedly owned considerable real estate in Nashville, dressed like a bishop, and appeared as a “thoroughly poised negro of the straight strain.” At a time when secretaries and clerks were men, he traveled with “a female secretary named Callie House.” The press also reported falsely that hundreds of witnesses had appeared in court. A story in the Nashville Banner of March 5, 1901, erroneously reported the filing of twenty-two cases against Dickerson already and that he and House had “reaped a rich harvest.” In a March 6, 1901, article the Banner inadvertently affirmed the grassroots support for the Association by complaining about the proliferation of chapters “in almost every little hamlet and village throughout the south.”

The Georgia State Supreme Court summarized the case very differently from the news stories: a local court had convicted Dickerson of “swindling” for his organizational activities in March 5, 1901. The judge had sentenced him to a fine of $1,000 and twelve months on the chain gang. However, the prosecution introduced only one witness, who accused Dicker-son of selling three membership certificates for seventy-five cents each, promising to send the money to Vaughan’s group in Washington and failing to send the funds. Dickerson testified that he had had no dealings with Vaughan and had never said he did. A local mutual assistance fund for burying the dead and caring for the sick controlled the funds in question. The State Supreme Court overturned Dickerson’s conviction on July 22, 1901. At a time when most cases went no further than the local courts, the Association used its limited funds to pay for the appeal.28

The Georgia State Supreme Court, removed from the local judge’s rhetorical battering of the ex-slave pension cause, treated the case as a routine fraud charge. They announced that in order to swindle, Dickerson needed to state that pensions had been passed, and not that he wanted legislation enacted, a perfectly legal organizing goal. In August, two weeks after the State Supreme Court decision, Wills told his superiors that, unfortunately, Dickerson’s conviction had been reversed but that he “had a good time for thought, having been confined in jail for a number of months” for not posting bond. However, Dickerson remained a “bad fellow, and I should to wonder if his confinement has given him an opportunity to invent new ideas to start in the work again.” They would “watch and wait,” he told his superiors in Washington.29

The prey the federal officials were determined to ensnare was Callie House. The production of the single witness against Dickerson and his prosecution seemed tied to the efforts of A. Wills and others in the Post Office Department and the Pension Bureau to make a case against her. Secretary of the Interior Ethan A. Hitchcock wrote to the postmaster general on March 18, 1901, forwarding a letter from Commissioner of Pensions Evans about Dickerson’s conviction. The forwarded letter stated, “Callie House (Dickerson’s Private Secretary) was charged with being implicated with Dickerson in this matter but could not be located and arrested.” Meanwhile, Wills insisted that the department should have House prosecuted in Atlanta. He made it clear that he regarded her “as being as bad, if not worse than Dickerson.”30

The postmaster general’s office passed along the false information that Dickerson had been convicted and House charged to its legal department to include in a review of whether to grant the Association’s request to lift the fraud order. The post office cited the Dickerson “conviction” and the implication of House as a reason to refuse the revocation of the fraud order. Federal officials made the most of Dickerson’s “conviction” in attacking House.31

Struggling to stay afloat, House and the local chapters repeatedly used not only the more expensive railway express but the names and addresses of various other individuals as mail recipients. However, House’s name on anything raised suspicion. On September 25,1901, the post office issued a fraud order against Delphia House, Callie’s middle name and the name of her daughter, and A. W. Washington of Arcola, Mississippi, when Washington sent Delphia a money order for $1.80. The Arcola postmaster, on the alert for anyone involved in the movement and seeing the name House, stopped the letter, claiming that it had been “mailed open,” which gave him an excuse to read it. The quite innocent letter asked for twelve membership certificates at fifteen cents each, stating, “I wants them so I can Collected National annual Dues from each member.” Washington said she had received their notice about trying to have the fraud order revoked to “give us a clear speech with each other and our Governments.” She had had extra meetings and would send $5 “on that fraud order to help have it revoke pass.” Her local chapter “wants to hear Prof. I. H. Dickerson very bad.” If he would come, they would “take care of him and pay his way down and back home from Nashville.” The correspondence indicated strong local support for the movement, which only increased the federal officials’ anxiety over the impact of the ex-slave pension cause.32

Mrs. House complained repeatedly about the denial of their First Amendment right to petition and the unfair lack of due process involved in the government’s harassment of the association. She insisted that the unreviewable powers of the government could lend themselves to abuse. As if to validate her concerns, in 1904 the Justice Department indicted Harrison Barrett and Assistant Attorney General James Tyner, nephew and uncle, as well as the two principal Justice Department officials who harassed Mrs. House and the association, for collusion to profit by abusing their discretion under the fraud laws. Tyner, age seventy-seven, who had served as postmaster general under President Hayes, was planning to close out his career as assistant attorney general for the Post Office Department.

However, first, Barrett left for private practice. Then he and Tyner colluded to influence businesses to retain his services for protection against the possibility of a fraud order. Since Tyner remained in the government, he could ostensibly have decided to target any business he chose. Upon entering office, the Roosevelt administration found the Post Office Department filled with corruption and began an investigation. As a result, Tyner was accused of bribe taking. His wife and her sister, apparently Barrett’s mother, went to his office and secretly took all the documents from the safe. When Postmaster General Payne learned they had been there, he chased them through the streets of Washington in his carriage, ending up at their house. They refused to admit him. Tyner and Barrett admitted that the charges were valid. However, based on a legal technicality they were acquitted.33

Needless to say, Barrett and Tyner did not offer the Ex-Slave Association the same insulation from fraud orders they dangled before businessmen to collect bribes. They knew the association of impecunious freedpeople could not afford the prices they charged. Their crimes, however, only underscored the unfairness in the Post Office Department’s use of fraud orders.34

After Dickerson’s conviction and the continued harassment and denial of personal mail, Mrs. House began to fathom the deep-seated hostility of the Post Office and the Pension Bureau toward their cause. The association could do little about scam artists and impostors except to report them. However, the officers continued to try to respond to the government’s concerns. As she continued her work in the cause, House did not yet accept the reality that federal officials would remain unsatisfied until the association completely abandoned the pursuit of pensions.