CHAPTER 6

Avoiding Destruction

More real harm is probably done by … regular agents…arousing as they do, false hopes concerning a supposedly overdue restitution of Freedmen’s Bureau funds, or reparation for historical wrongs, to be followed by inevitable disappointment, and probably distrust of the dominant race and of the Government.

COMMISSIONER OF PENSIONS H. CLAY EVANS

(1902)

BETWEEN 1901 AND 1915, Mrs. House and the harassed and beleaguered Ex-Slave Association continued to organize local chapters to deliver medical and burial aid to aged members and their families. Association members also continued to collect petitions, believing that recording as many ex-slaves as possible and petitioning the government was not only right but might eventually succeed, although they became increasingly embittered about federal harassment of the movement. Government officials continued to treat them as second-class citizens, unentitled to behave as political agents or free Americans. However, Mrs. House’s persistence kept the movement alive.

House felt little joy at the celebrations of the new century. The expositions and fairs and the widespread expressions of hope that human aspirations would be realized through the wonders of technology and quickened social awareness held little meaning for her. Mrs. House’s cause to help the poor exslaves would seem to have been attractive to progressives, who worked to cure social ills ranging from impure food and drugs to housing for urban immigrants, but wider support remained elusive. A few white progressives helped to found the NAACP and the National Urban League, but nationally whites paid little attention to solving the race problem or to the claims of ex-slaves. The Republican Party platforms of 1900,1904, and 1908 had planks insisting upon the protection of black voters. Twelve more years of Republican control only saw the problem grow in magnitude. Equal protection under the law remained unenforced and the plight of blacks ignored. Between 1901 and 1910, newspapers reported the lynching of at least 846 persons in the United States. Of this number, 754 were African Americans. Ninety percent of the lynchings took place in the South. The largely unresponsive state and federal governments did little or nothing to remedy the abuse.1

While Mrs. House and other African Americans mobilized mutual assistance associations and civil rights organizations, mainstream newspapers’ race coverage was largely devoted to stories about the threat of supposed “black-beast rapists.” The papers also reported such sensational stories as a white woman in Chicago explaining that she had lived with a “Negro” for twelve years because he had held her “captive” in his apartment, too afraid to leave even when he went to work. Such limited documentation of the black experience was augmented by an occasional piece on the professional interests or leisure pursuits of the local African-American business and professional class. Meanwhile, African-American newspapers focused on social engagements, self-help activities toward progress for the race that made no demands on whites and did not upset the established order, and articles on Jim Crow and the absence of civil rights. These papers continued to ignore the embattled pension movement, the loyalty of its members, or its potential for the working class, barely educated nobodies and the poor.2

Also, in Nashville, the home base of House and the ExSlave Association, African-American business and professional leaders totally ignored House and the ex-slave pension cause. For these African Americans, the major stories of the early years of the twentieth century included an unsuccessful boycott of Jim Crow streetcars in 1905. It also included the founding of the Globe by Richard H. Boyd to support the boycott. The newspaper lasted into the 1960s as a voice of middle-class activities and aspirations. Black leaders also pointed proudly to the opening of a segregated public university for blacks, in 1912, the Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial (A&I) College, in a period when such colleges were being established by state governments throughout the South. Because of the presence of Meharry Medical College, the black private colleges, the National Baptist Publishing Board, and then Tennessee A&I, Nashville’s professional class of lawyers, physicians, and dentists grew. The city also had a middle class of barbers, ministers, teachers, and semiskilled laborers. These groups were of sufficient size to support Greenwood Amusement Park, the Globe, and a number of civic and social organizations. African-American shoemakers, liquor dealers, blacksmiths, and barbers started to lose to white immigrant competition in 1900-1910. But the businesses that primarily served blacks continued to prosper by serving a segregated “captive” population.3

African Americans probably thought the Jim Crow chill in the early-twentieth-century air would diminish when, in office only a month, President Theodore Roosevelt not only invited Booker T. Washington to the White House but dined with him during their discussions. The incident outraged white southerners, but blacks hoped this social interaction would lead to a new commitment to punish lynching, ensure access to the ballot, and overturn Jim Crow. Mrs. House and the Ex-Slave Association thought it might lead to an end to their exclusion from the mail service; however, beyond the affirmation of Booker T. Washington’s control of patronage, little of substance resulted.4

By the fall of 1901, Mrs. House and the other Association officers desperately needed the fraud order lifted. Their struggle to keep in touch with agents, the membership, and their families required a great deal of money, time, and energy. Members paid twenty-five cents, collected as an initiation fee, of which ten cents went to the territorial or state council; ten cents to the national; and five cents to the organizers and agents for each new member recruited. The ten cents paid monthly remained in a local fund for use as decided by the chapter for the mutual benefit of members. The national office utilized its funds to prepare and distribute literature, hold conventions and meetings, and to maintain the membership rolls and petitions. Special contributions paid for lobbying. General Manager Isaiah Dickerson’s clerks kept the books and gave receipts to state agents. Callie House lectured and organized chapters and petition signing throughout the South. The association had to pay W. C. Lawson, its first attorney, hired to lobby in Washington when it decided it needed a professional to work on the association’s behalf. In 1899, they paid him $204 for his work. The Association made a few changes in administration in order to restrict the impact of the government’s campaign. In addition to using railway express services, Mrs. House and the agents had to collect funds and distribute materials personally rather than through the mails after the issuance of the fraud order. Also, the board of directors increased the initiation fee. It became “so much harder to obtain enough money to travel from place to place that they raised the amount to fifty cents, including twenty-five cents for the agent.”5

In addition to the changes in operation, the Association decided, in November 1901, to hire an experienced white Washington lawyer, Robert Abraham Lincoln Dick, to seek repeal of the fraud order. Dick specialized in pension matters and had been a law partner of Walter Vaughan at one time. He could see that the government was engaging in selective enforcement. He knew that the Post Office Department had not issued a fraud order or otherwise harassed Vaughan despite his profit seeking in selling his pamphlet and organizing his clubs. Dick believed that

The condition of the colored people in this country today and especially in the south brings forward a number of grave and serious questions, commercial and social as well as political, and the ablest statesmen as well as accomplished scholars and big-hearted philanthropists differ as to a solution of or a remedy for those conditions. The trend of opinion, however, seems in the direction that a national government response is required. A dozen different propositions have been advanced and the pensions idea to some people appeals with as great force as does the colonization idea to others.

He also knew that “the luxury of today becomes the necessity of tomorrow.” And that “a few years ago was generally regarded as a dream or an absurdity is today existing fact.” He also saw that Callie House and her colleagues “believe that by education and agitation and with a strong organization appealing to Congress that eventually their appeal shall be listened [to] and they [are] earnest and honest in their belief and are acting in good faith.”6

At this time social reformers in the United States routinely sought inspiration, approval, and support from their British counterparts to influence American public opinion. Ida B. Wells had successfully persuaded the British to condemn lynching. Jane Addams modeled the Settlement House movement on private British social welfare programs. Dick knew that the British idea of giving pensions to needy subjects sixty-five years of age or older was under serious consideration. Previously the idea, he surmised, “would have been laughed out of the Parliament with ridicule and contempt.” However, having so many “feeble and decrepit people to support and the method of providing for them raises a serious question this as a matter of analogy.”

Dick also thought that if President Lincoln had lived the southern slave owners might have been paid a million dollars for their slaves as one of the conditions of Reconstruction; also that the “poor unfortunate ex-slaves would have been helped other than merely being told ‘you have your freedom like the animals and the birds,’ now be thankful and fend for yourself.” He also could not understand why the officers of the Ex-Slave Association could not “advocate these positions and not be guilty of any fraud.”

Dick met with Post Office Department and Justice Department officials and explained that members joined the association for a perfectly valid reason: they received mutual assistance for burial or medical costs. But in promoting pensions they gained “the influence and power of organization and association, exchanges of opinion and ideas. The pieces of literature books etc., the attendance upon lectures, debates etc are all potent factors in benefitting mankind in general and especially those who attend such things with proper, lawful and moral motives.” He also carefully outlined how the association handled its financial affairs in the usual pattern of such organizations.

The officials asked him why the mutual benefit features were not mentioned prominently in the association’s national literature. He explained that “as in some other fraternal organizations” these benefits were controlled by the local councils. House and the other national officers and board “had nothing to do with the benefit fund, which remained in local hands.” In order for them to be able to check his responses, he provided the names and addresses of local council heads, who could provide the names of members who had received a death or sick benefit or funeral expenses, in New Orleans; Vicksburg, Mississippi; Atlanta; Kansas City, Missouri; and other cities. Postal and Justice Department files indicate no effort to investigate the work of the local chapters or even to make inquiries of them.

The officials also asked Dick whether House and Dickerson had attempted to recruit African Americans by leading them to believe they could collect pensions only by joining the Association, if and when legislation passed. He responded that he had heard rumors but found no evidence to support the charge and that none of the literature contained such inducements. Finally, departmental officials asked whether the association had any credibility at all since, surely, Dick knew that Congress would not enact pensions for the ex-slaves. By their calculations, at least 7 million possible recipients would receive $10 per month, which would amount to more than $210 million annually. No rational person could believe Congress would ever appropriate such amounts or even a quarter of the total.

The officials exaggerated the costs since only persons who had actually been held in servitude would have been eligible, not the entire black population. In 1900, only 21 percent of the African-American population, or about 1.9 million persons, had been born in slavery. Their numbers, like those of the veterans under the lucrative Union pensions provisions, were slowly diminishing due to deaths.7

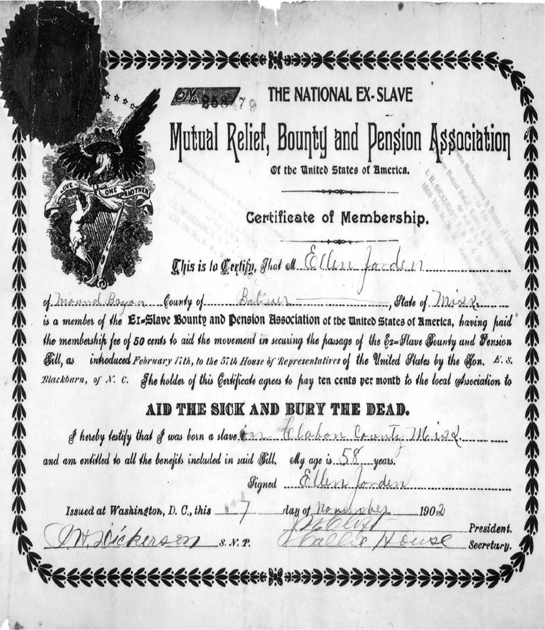

House and the officers decided to invite more federal scrutiny of their activities by holding their sixth national convention in Washington, D.C., on October 29—November 1, 1901. The board also acted on Attorney Dick’s advice that the association reincorporate in Washington, D.C., in February 1902. It also issued new literature and membership certificates explicitly mentioning aiding the sick and burying the dead as local chapter functions. The Association also persuaded Republican congressman Edmond Spencer Blackburn of North Carolina to reintroduce the pension legislation in the House of Representatives, despite their experience with the Senate committee’s 1900 negative report.8

Their efforts seemed to have borne fruit when Dick reported to the Association board that all signals from the officials at the Post Office Department indicated that he had succeeded in lifting the fraud order. The department “had decided to let the organization have the use of the mails & that there would be no further interruption so long as the organization and its officers complied with the strict observances of the law. So I trust that the organization & its officers will bear this in mind and strive to obey the law in all its requirements.” He told them that the local chapters must strictly “act in compliance with the Constitution of the Supreme National Organization.” If they failed to do so, they would “impair their usefulness to the general cause for which the association is in existence.”9

House and the Association rejoiced at Dick’s good news, but he had been misled. Without telling him, government officials had not only continued the fraud order, they had enlisted the aid of a private organization to help destroy the ex-slave movement. The Grand Army of the Republic, founded in 1866 as an organization of veterans of the Union military during the Civil War, had become a powerful influence in electoral politics and had great success in increasing veterans’ pensions. Callie House and her association colleagues had no way of knowing that the commissioner of pensions, H. Clay Evans, had written to Eliakam “Ell.” Torrance, commander in chief, Grand Army of the Republic, on February 7, 1902, asking him to help squelch the movement. Torrance, a veteran of the Union Army’s Ninth Pennsylvania Reserve Corps, played a major role in reconciliation and reunion activities between white Union and Confederate veterans of the period. He served as chairman of the Gettysburg Fiftieth Reunion Committee. Commissioner Evans explained to Torrance that pension organizers had been too successful. The bureau knew of “ninety organizations… in a single southern state.” Each local chapter was constituted of at least twenty-five members. Some of the organizers were “impostors,” he told Torrance, and at least two white men who had taken advantage of the situation had been convicted and sent to prison. But “More real harm is probably done by…regular agents…arousing, as they do, false hopes concerning a supposedly overdue restitution…or reparation for historical wrongs, to be followed by inevitable disappointment, and probably distrust of the dominant race and of the Government.” He wanted Torrance to have department commanders in the South “protect members of the order and others associated with them by advising post commanders as to wherein the movement has been used by designing persons to live at the expense of the colored people through grossly fraudulent representations,” and warned that members should have nothing to do with the idea. Since there would be no reparations, suppressing the movement served the interest of the government and the ex-slaves.10

Now aided by the Grand Army of the Republic, the government continued to deny the organization the use of the mails. Dick told House and the other Association officers about a new third party to promote pensions. Some white former pension allies of Vaughan had “hit upon” the idea of organizing such a party, and when it was announced in Washington, Vaughan christened it “Vaughan’s Justice Party.” Vaughan had decided that “existing parties will never do justice to the south” by relieving them of the burden of ex-slaves by pensioning them. Dick thought that a party to support their cause was a bad idea. He sent the association’s board and the Pension Bureau a copy of his letter of March 21,1902, to Hadley Boyd, a Vaughan supporter, of Washington, D.C., who had asked for his help, saying that while he supported pensions, he thought the idea counterproductive. “History and experience teach me that but two substantial, permanent political parties can successfully exist under our form of government contemporaneously, and the more equally and evenly divided these two parties are in numbers, influence etc. the safer stands the government and its institutions.” He believed that if people energized themselves emphatically, they could get the existing parties to respond to their concerns. Parties spasmodically come into existence, but like “a meteor they flash across the political sky and then fall dead into the arms of mother earth.” Although there had been third-party challenges, including the Populists and Eugene Debs, none had been successful.11

Dick agreed with House and the other leaders of the association that they should regard President Roosevelt’s dinner with Booker T. Washington as a good omen. Emboldened, he sent Roosevelt press clippings, a petition, and a description of the association’s objectives and asked for his endorsement of the cause. He hoped Roosevelt would instruct the federal officials to tolerate the movement. He also insisted that the Association cooperate by forwarding to the Post Office Department any rumor of impostors. They apparently received no response from the White House, and no improvement occurred in official behavior toward the Association.12

As part of their strategy, still believing a lifting of the order imminent, on April 6, 1902, Callie House and the board accepted Dick’s advice to select new officers in the hope that this might please the government. Because she appeared to have become a specific target, House agreed to continue as an organization leader, traveling, lecturing, and enrolling members, but to no longer appear on the list of officers and board members. They also gave Dickerson the title of national lecturer and elected A. W. Rogers general manager, Reverend J. W. Clift president, and Robert E. Gilchrist of Washington, D.C., financial secretary. One month later Dick responded to the government’s request by taking Dickerson to a deposition at the Pension Bureau to show their willingness to help with the investigation of alleged imposters. He answered every question, but bureau officials seemed more interested in the association than in pursuing anyone else.13

In response to a question, Dickerson answered that he had originally managed Vaughan’s organization when he had conceived the pension idea. However, Vaughan was not involved with the association. Dickerson told the officials that before he became a pension advocate he had taught school throughout Tennessee. When asked whether he had “collected thousands of dollars from these old ex-slaves all though the south,” he answered no. “The association have [has] collected it and a great deal was paid for publication and railroad fare.” He allowed that some of the money might have been embezzled by dishonest agents. In response to a query, he said he did not know whether any of the funds had gone to members of Congress to encourage their support of the legislation.14

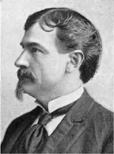

Commissioner of pensions Henry Clay Evans (served April 1897-May 13,1902), Union veteran, businessman, and former member of Congress, believed that the movement should be stopped as a danger to public order whether its leaders were honest or not. “Men Recently Chosen for Diplomatic and Other Public Service,” Harper’s Weekly, 1897.

Ell Torrance, Minnesota judge who was commander of the veterans’ organization the Grand Army of the Republic, was asked by Evans to aid in crushing the movement.

Despite the complete cooperation and openness of the ExSlave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association, federal officials continued to enforce the fraud order. Withstanding the obstacles and strains, Mrs. House and her colleagues continued their work. On February 9, 1903, Nashville postmaster Wills wrote to the assistant attorney general at the Post Office Department that an enclosed news clipping from a local paper, The Nashville Tenn Daily News of February 6,1903, showed the continuation of the “same old steal.” It appeared that “Dicker-son, Callie House and others are still interested in the matter.” The news clipping gave Wills credit that the Association’s activities “were finally driven from here through the action of your department.” The article reported the arrest of B. F. Crosby in Montgomery, Alabama. Wills claimed he worked for the association. Furthermore, the paper stated that a newspaper published by the association at that time, the Freedmen’s Headlight, had promised the payment of pensions by a specific time.15

Upon inquiries from the Post Office Department, attorney Dick gave officials copies of the newspaper to review. Each edition of the Freedmen’s Headlight clearly stated that the pension bill had not passed. In one issue a front-page article by George Green, one of the founders of the New Orleans chapter, reported that the association continued to work despite the federal fraud order. As a result of its efforts, “there have been bills introduced six different times in the Louisiana Assembly on the subject.” He also went with a delegation of “southern colored gentlemen” lodge members from the Southwest, who presented a petition on behalf of those who wanted pensions to President Roosevelt. The president promised he would give the matter his “careful consideration.” The article went on to extol the work of Mrs. House and Dickerson but stated, “If we fail in our efforts it will be no more than other great moves have done, and the people of this great nation will give those who worked in good faith credit for asking the government for something for what we thought was just and right. We will be like the South. They fought for what they thought was right, hence our position in this matter.” The statements included no intimation that the legislation had passed.16

Crosby said he had been an Ex-Slave Association agent for four years. He had been arrested, according to The Nashville Tenn Daily News clipping of February 6,1903, when some local citizens complained that pensions did not arrive in January. However, in their eagerness to find criminal activity, neither Wills nor the other postal officials examined the Nashville newspaper very carefully. The same paper indicated that the language of the certificate included the following language:

This is to certify that Mrs. Linda White is a member of the Association, having paid the membership dues of fifty cents to aid the movement in securing the passage of the ex-slave bounty and pension bill The holder of this certificate agrees to pay ten cents per month to the local association to aid the sick and bury the dead.17

Neither the certificate nor the Freedmen’s Headlight asserted that the pension bill had passed. It also specifically affirmed the importance of the mutual-aid function of the association that so attracted members.

The association held a mass meeting in Washington, D.C., at Samaritan Temple between Second and Third on I Street, on February 12,1903, to gather support for the pension bill, which had been reintroduced for the new session of Congress by Congressman Spencer Blackburn of North Carolina. According to The Washington Post, the meeting was attended by “a large gathering of colored citizens of both sexes.” Dickerson told the group, “If the government don’t pay us a cent it will always owe us. The ex-slave bill is not a fraud.” The meeting passed a resolution thanking all those who supported the effort to pass the bill.18

As House continued her Association work, her disappearance from the list of officers confused postal officials. Inspector J. H. Wilson of the Washington, D.C., post office was assigned to solve the mystery. He expressed agreement with his bosses’ suspicions but found nothing illegal. Inspector Wilson wrote to Captain W. B. Smith, inspector in charge, that two ex-slave pension organizations operated in Washington, the Ex-Slave Association and S. P. Mitchell’s Industrial Council, a small expension organization. Wilson thought perhaps House had become active in the council since she was no longer an officer of the association. However, he had no evidence that she was. Whatever her role in the association, everyone knew she spent her time working in the southern states. He read the literature of the Industrial Council and the Association and saw nothing illegal. There simply was no information that would lead to extension of the fraud order against the association or its application to the Industrial Council. The government had no information on mailings or any possible House connection that supported legal action. But they continued to exclude the association from the mails anyway and kept watch on the Industrial Council for any signs of connections with House. The assistant attorney general promised to keep the case open, as “something might develop later.”19

The assistant attorney general and Post Office Department officials continued to reach conclusions about the movement without investigating the association’s local chapters or their activities in local communities. Government officials did not follow up on the names and addresses and other information provided by the association. Instead, the government investigated only to determine whether Callie House, Dickerson, or some individual possibly connected to them was continuing their organizing work. Following a policy of harassment and disdain for the organization’s existence and despite the lack of evidence of illegality and Dick’s assurances, the Post Office Department issued another fraud order against the Ex-Slave Association on October 28, 1903. The order prohibited the payment of money orders or the delivery of letters to the association or to Dickerson, Gilchrist, or any other officers. The 1899 order against House personally still stood. The reorganizations, the full disclosures, and the absence of Mrs. House from the official leadership had no positive effect with regard to relieving the government harassment.20

Then the U.S. Supreme Court strengthened the Post Office Department’s hand in dealing with alleged fraud. The high court had only once before reversed a postmaster’s decision and in no case did the Court deny the power of Congress to give unfettered authority to the Post Office Department. In the first test case under the 1895 amendments to the fraud section, American School of Magnetic Healing v. J. M. McAnnulty, (1902), the Supreme Court affirmed the postmaster general’s full and absolute authority over the mails. However, the high court did not agree that magnetic mind healing necessarily constituted fraud. Justice Rufus Peckham stated that the postmaster had no facts that proved that such healing did not work.21

Two years later in the Public Clearing House case, the Court denied a request for an injunction to prevent enforcement after the Post Office issued an order. Public Clearing House acted as the fiscal agent for a voluntary association for unmarried people; each person paid $3 as an enrollment fee and $1 a month for sixty months. If the individual had not married in a year, he or she received a certificate worth $500. The Post Office Department decided that this was a lottery and the organization could not use the mails. Justice Henry Brown, with Justices David Brewer, Edward White, and Oliver Wendell Holmes, concurred in an opinion that had far-reaching consequences: “The postal service is by no means an indispensable adjunct to a civil government.” In other words, no one had the right to use the mails, and therefore matters concerning the post office were not subject to government rules of due process. This body of law gave no recourse to Mrs. House in her effort to have ex-slaves organize to use mail service as they expressed their citizenship rights to petition the government.22

While Callie House tried to keep the ex-slave pension cause alive, she hoped for some support from leaders in the Nashville African-American community, but they had other priorities. They were focused on the boycott of 1905, blacks’ response to a new state law specifically reinforcing segregation on streetcars, except for “nurses attending or helpless persons of the other race.” Blacks walked instead of riding public transportation until Preston Taylor and others organized their own transportation company. The company ultimately failed, in part because of a $42-a-car privilege tax on cars the white city government promptly enacted. Thereafter, the protestors settled into accommodating themselves to segregation, while poverty and racism still hampered the ex-slaves and their progeny in the poor black neighborhoods.23

The Association was in deep financial difficulty, and the legislative effort seemed stalled. Federal harassment of the ExSlave Association slowed the receipt of membership dues to a trickle. The chapters continued to provide mutual assistance but national political action came almost to a halt. Each time the association sought revocation of the fraud order, the assistant attorney general requested another supposed “investigation” of their current affairs. After the usual lack of investigation, government officials always reached the same conclusion: that Mrs. House and the others were “colored agitators and crooks.” This time inspector G. B. Keene reported that the national office of the association had not actually carried on any activities in two years since the fraud order “choked off” their resources. He calculated that since June 1905, based on intercepted mail, $95.53 had been collected and $62.93 disbursed, but a “considerable bill” for office rent had gone unpaid. Also, according to Keene, the secretary’s salary of $5 per week had not been paid in full. The association was bankrupt. Again, the officials made no effort to investigate the local chapters’ activities. Keene thought the fraud order should stand. Basing its decision on the report of inspector Keene, on January 18,1906, the Post Office Department denied the application for revocation.24

While the Association appealed to federal officials, developments in Congress further strengthened the Post Office Department’s hand. Assistant Attorney General Tyner expressed the same concern that association lawyers and others had raised about the postmaster issuing fraud orders without due process and suggested that individuals should have the right to a speedy appeal of such orders. However, Tyner was precisely the wrong person to lead the cause, as he had been identified as one of the principal corrupt officials in the Post Office Department. Everyone assumed that Tyner, upon his imminent retirement, wanted to protect clients from enforcement of the orders.25

James Tyner, assistant attorney general for the Post Office Department, authorized Harrison Barrett, his nephew and assistant, to harass the association with a fraud order. The order closed the mails to the group.

However, Congressman Edgar Crumpacker of Indiana, as persuaded as Mrs. House was that there was a due process problem, followed up by introducing a bill that would have impounded the mail while a hearing and judicial resolution took place. He complained that the number of fraud orders, most of which constrained business enterprises, had increased to 630 in the preceding two years, 71 more than in any four previous years. In addition, during the preceding year, every request for an injunction had been denied. The courts had said complainants could obtain a review of the decision but not of the facts to determine whether fraud actually existed. Crumpacker’s bill required judicial review of the law and the facts. Although the Judiciary Committee supported it, at first unanimously in January 1907, the Post Office Department ultimately managed to kill the legislation.26

Postmaster General George Cortelyou went public in April 1907 in an article in the North American Review, vigorously defending the existing procedures as in the public interest. Cortelyou, who presumably had the support of the Roosevelt administration in whatever he did, had extensive connections within the president’s party. A New Yorker, he had been secretary to several powerful men, including Presidents McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. As chairman of the Republican National Committee in 1904, he had conducted the campaign that elected Roosevelt. He brooked no interference with or curtailment of his powers as postmaster general. Cortelyou also had Tyner’s support of the legislation as an easy target. The postmaster insisted that fraudulent enterprises would simply continue to gouge the public during the legal appeals and that judicial review in advance would compromise the post office’s work of protecting consumers. In response, the Senate simply buried the bill in the committee. The Congress and officials within the department and the Roosevelt administration had squelched attempts to introduce reform and thwarted a measure that might have given due process to the association. As a result, the post office remained unfettered in making unilateral decisions on the subject.27

Mrs. House and the Association decided to try again to have the fraud order lifted. This time, on April 20,1907, Attorney Thomas Jones, representing R. E. Gilchrist, born a slave in Virginia in 1847 and the Association’s new secretary, wrote Assistant Attorney General R. F. Goodwin, asking that the fraud order be revoked. The letter explained that whatever had happened before, “future business methods here in Washington as elsewhere shall be clean.” Gilchrist had not known of the fraud order when he was elected, but he also knew of no “wrongdoing” by Dickerson, Callie House, and others.28

The board of the Association expelled Dickerson, despite no evidence of “wrongdoing” on his part, hoping that would please the officials. Being “embarrassed and interfered with,” Gilchrist wanted the fraud order withdrawn. He still believed the ex-pension measure was “a just one, and should be agitated by every intelligent colored man, until sufficient sentiment is created as will cause the enactment of some measure to relieve.” He pointed out that the group had new officers: A. W. Rogers of Williamstown, N.C., had been president of the association since May 1904, and Parker Moten, a Washington, D.C., shoemaker served as treasurer. When Rogers arrived in Washington to lobby for the association, The Washington Post reported that he hoped to achieve passage of a law to pension the ex-slaves.29

Despite her previous experiences, Mrs. House harbored a faint hope that this time the effort would succeed. No one involved with the Association realized that no matter what they said or did, the government was bent on suppressing the pension movement. But then the assistant attorney general’s response on May 16,1907, made clear that the problem was the very existence of the pension movement. He pointed out that in the meeting on April 18, Gilchrist had “state[d] plainly his intention of continuing to promote the same business.” The letter stated that not only would the department decline to revoke fraud orders against businesses and other institutions, it would not permit Gilchrist to use the mails individually unless he withdrew altogether from the pension movement. Just as the Post Office Department had done with Mrs. House, Dickerson, and other officials, the Association’s new leader could not personally send or receive mail. Gilchrist refused to withdraw from the association, and the order remained in force.30

The Association reorganized twice, to no avail. It clarified its mutual-aid function in their certificates and literature and elected new officers—excluding Callie House—hoping to reduce any antagonism caused by her defiance and the outspoken letters she had written to officials. The second reorganization and the expulsion of Dickerson had still garnered nothing. They did not understand at first how deeply committed the officials were to stopping the movement. Prosecution of obvious impostors and fraud orders against bona fide leaders in the movement provided a rationale for cutting off all financial support and mail, even from leaders’ friends and family, until the Association leaders had no alternative except to stop the work. Pension Bureau and postal officials repeatedly made a judgment that the pension idea undermined the national interest, which was keeping African Americans passive; the Association, the officials asserted, misled “credulous” African Americans, who did not understand that legislation would never pass. Because the organization and its leaders must agree that they would fail, they engaged in fraud by continuing to operate as if they had a chance to succeed. By the same standard any organization devoted to a remote, or an improbable legislative goal, was at risk. Gauged by such a measure, the NAACP’s long and unsuccessful struggle to gain an antilynching law could have been considered fraudulent.

In an effort to satisfy federal officials, this new certificate displays prominently the mutual assistance work of the association chapters.

Over the next few years, federal officials continued to fill their files with “sightings” of persons erroneously identified as Dickerson or Callie House. These imposters used their names to collect money from freedpeople. For example, on January 24, 1905, the president signed Senate Bill 2009, giving a pension to white veteran Richard Dunn of Cambridge, Maryland. Richard Dunn “colored,” of Chattanooga, wrote to the bureau that someone he identified as “L. Dickerson” had put a mark on the Congressional Record by the white Dunn, told him he represented the government, collected one dollar, and claimed that they, as ex-slaves, would receive a pension. He said Dicker-son also collected from other “colored” men. He wanted to know if pensions had been enacted. He described Dickerson as about forty years old, five feet, four inches tall, and weighing about 160 pounds. Even H. V. Cuddy, chief of the Law Division of the Pension Bureau, admitted that Dickerson did not fit the description of the man described but in passing described Dickerson as “an extremely smooth talker” with “the delivery of a trained orator.” He did not know Dickerson’s whereabouts, but the Washington office had been closed for more than a year. Cuddy noted that Dickerson had worked with Cal-lie House, but erroneously described her as “a thin-faced mulatto, who writes a fairly plain hand, and is an excellent talker.” Callie House was in fact a dark, heavyset woman. Cuddy thought that bureau officials should take testimony from Dunn to see if they could establish that he had given Dickerson money because he represented himself as a government employee. If so, they could prosecute Dickerson, Cuddy hoped.31

The post office seemed to view every piece of information it received as another opportunity to cast suspicion on Callie House. On December 28, 1906, Nashville Postmaster Wills wrote to Washington that he had a letter addressed to Thomas House that had previously been sent to her from the same address and returned to sender. On December 26, 1906, the superintendent of letter carriers told Wills that he thought the writer wanted to reach her by using Thomas House as an addressee, which “I believe to be a fictitious name used by Callie House.” On March 11, 1907, Wills responded that even though he had made no investigation he thought the letters addressed to “her brother” Thomas belonged to her and that the mailing “indicates to me she still continues the fraudulent business, and I think the case should be investigated at an early date.” Callie House, indeed, asked correspondents to send letters to her children, including Thomas, hoping to communicate with the chapters. However, they could have easily ascertained Thomas’s identity. The Nashville City Directory included the information that Callie House and Thomas House, her son, who worked as a railroad car cleaner, lived at the same address.32

The association continued to hold annual conventions without interruption despite the federal harassment. At the June 1907 convention in Washington, D.C., at Miles Memorial Church, A. W. Rogers of Newbern, North Carolina, presided as president. Reverend L. E. B. Rosser, pastor of the church, spoke, as did Armond Scott, a Washington attorney. The resolution endorsing the pension bill took a new tack; adding the rationale pushed originally by Vaughan: “to refill the depleted treasury of the South, made so by the ravages of war.” The strategy did not gain more support in Congress.33

On November 26, 1907, when inspector W. E. Greenaway asked what “is the status of this case?” Wills, the Nashville chief postmaster, replied, “Petered out entirely. The parties have evidently quit business—because we made it too hot to continue.” The post office believed it had successfully killed the organization by stopping its mail.34

A change in the White House after the 1908 election did not change the government’s stance toward the association. However, Mrs. House and other advocates continued to collect signatures and to organize in the ex-slave pension cause, even though the new Taft administration appointees and career officials in the Pension Bureau and Post Office Department continued their harassment. After Dickerson’s death in 1909, Mrs. House, described in the 1910 Census as a “traveling Lecturer” for the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association, stayed on the road even more than before. Her children were able to care for themselves; the youngest child, Annie, was sixteen, and Mrs. House’s brother and his wife still lived next door. Mrs. House collected funds personally at local meetings and carefully stretched whatever she received to pay her fare to the next place. She met with agents and supervised their work. She stayed with local chapter members and had them send correspondence to her family. The group also had to hold more frequent local meetings to share information, instead of distributing flyers and other materials because of the government harassment. Association officers also tried to use intermediaries to send and receive mail pertaining to headquarters operations. None of these special efforts was easy and their movement suffered.35

Nevertheless, the association’s work in the field continued, as did the petition drive. In December 1909, the U.S. Senate took note of another set of petitions from ex-slaves that arrived at the Capitol but took no action. The petitions asked, as earlier ones had, for the passage of the bill by Senator Mason of Illinois, first introduced on June 6, 1898, and reintroduced in each Congress thereafter. The petition stated that the petitioners had seen service as slaves and believed they deserved pensions, just as did unknown and deceased soldiers. Only a few of the petitions remain in the government’s files. As with previous petitions, the pension seekers included their names, the names of their former owners, their ages, and their present addresses.36

From time to time the Post Office Department and the Pension Bureau would record rumors about Mrs. House and continuing meetings of people in the movement. On January 2, 1911, a constituent from Tuskegee, Alabama, M. A. Warren, sent Congressman Thomas Heflin a circular printed by a “negro preacher, for the purpose, I think, of fraudulently obtaining money from these negroes.” Warren thought the preacher had promised that money had already been appropriated in order to collect $5. He told Heflin, “I think you represent these old negroes in Congress as well as us white people, and if these claims of his are fraudulent, I think you ought to have the government put a stop to him and his association.” The local U.S. attorney told the assistant attorney general that under the “meager facts submitted” the state and not the federal government had jurisdiction so he should give it to the local prosecuting attorney. Still, neither the U.S. attorney nor local officials made any attempt to investigate whether the local chapter engaged in bona fide activities.37

A few complaints of alleged imposters continued to trickle in and the government used the complaints to reinforce the conclusion that the association was engaging in fraud. On April 24,1911, the postmaster general, F. H. Hitchcock, responded to the secretary of the interior concerning a complaint by Henry Parrish of Jackson, Mississippi, that alleged the use of the mails to defraud by two women, one of whom claimed to be Callie House of Nashville, Tennessee. He referred it to the chief inspector for handling. But the description of the woman did not fit Mrs. House. Congressman Swagar Sherley of Kentucky reported to the attorney general, based on a constituent’s letter, that “one of the negroes” employed by the Ohio River Saw Mill Company had given to an ex-slave association. He wanted to know if this violated the law because he believed that “ignorant negroes are being fleeced.” Assistant Attorney General W. R. Hair replied that they were sending the complaint to the Post Office for investigation because they had responsibility for the federal law that covered schemes to defraud through the mails. These complaints were simply acknowledged as additional evidence that the association still operated and as a reason to keep the fraud order in place.38

Even more positive political change in Nashville failed to attract the support for the pension cause Mrs. House still hoped for from African-American leaders. Locally, after William Howard Taft’s election to the presidency in 1908, division among the Democrats in the 1910 election permitted the first Republican governor since 1883, Ben W Hooper, to take office. He named an African-American adviser, a new man in town, Benjamin Carr. Also, President Taft revived James Napier’s political fortunes by naming him register of the Treasury, making him the first nationally recognized black leader from Nashville. Ben Carr was responsible for having Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial, the state college for “negroes,” located in Nashville. He also engineered the city purchase of the John L. Hadley former slave plantation and its development as the first public park for African Americans, dedicated in 1912. But Carr showed no interest in the pension cause. Federal departments did not modify their behavior toward blacks, and matters worsened when the staunch segregationist Woodrow Wilson became president.39

The association held its Nineteenth Annual Convention on November 23-27, 1914. House managed to distribute a report to members despite the federal harassment. She reported that they met at Mount Gilead Baptist Church in Nashville, pastored by Reverend R. Page. Reverend William Atkins of Lynchburg, Virginia, served as president. “Two white friends” visited the convention before the opening of the meetings and assured them that the movement would succeed someday in having the ex-slaves paid. She asked that contributors continue their commitment to the work and asked that they send any funds to pay expenses. Attempting to bypass the scrutiny of Nashville postmaster Wills, Mrs. House asked that they reply to 1219 William Street in Chattanooga.40

Despite the barriers they faced, the movement had kept up a level of momentum since its inception—albeit inhibited. The chapters continued to provide mutual assistance, and Mrs. House and local chapters continued to gather petitions and work for the legislation. However, even though members kept sending petitions to Congress, passage of the ex-slave pension legislation seemed increasingly unlikely. The movement needed another strategy.41