CHAPTER 9

Passing the Torch

My Whole soul and body are for this ex-slave movement and are willing to sacrifice for it.

CALLIE HOUSE

(1899)

IN AUGUST 1918, after her release from prison, Callie House returned to her family home in South Nashville. It was the same shotgun frame house she had lived in since a few months after moving from Murfreesboro in 1898 at the start of the national ex-slave pension movement. For the next ten years, until her death, Mrs. House worked once more as a washerwoman and seamstress in her neighborhood of porters, laborers, washerwomen, and domestic servants.1

Mrs. House’s conviction had killed the national legislative activities of the Ex-Slave Association. But the work of the local chapters and the reparations movement continued. Mrs. House’s work did not occur in a vacuum. The final decades of her life came at a time when conservative Republicans and Democrats dominated politics; liberal social trends vied with religious fundamentalism for political attention. In the African-American community, art and literature exploded in the creativity of the Harlem Renaissance while brutal repression, in the form of lynching and racial riots, seemed to increase. The NAACP began a concerted effort to end racism and bigotry, which included an initiative focused at obtaining a federal antilynching law.2

In Nashville, the city and the Carnegie Foundation opened a “Negro” library. The “colored” Young Men’s Christian Association occupied a large building in the heart of the African-American business district, and national African-American organizations such as the Baptist Convention and National Medical Association held their conventions in the southern city. African-American civic organizations abounded, their activities dutifully reported by the black-owned Globe newspaper. The state operated a segregated tuberculosis hospital to address the disease many whites saw as a “Negro disease.” Black churches flourished. So did taxpayer-supported all-black institutions, including Pearl High School, Tennessee A&I College for Negroes, which my eldest brother and numerous cousins attended in the 1950s and 1960s, and Hadley Park. These stood as accomplishments that local African Americans had requested successfully from politicians. In 1917, in response to another African-American demand, the state of Tennessee permitted a Nashville colored National Guard to mobilize for service in World War I.3

In the years following Mrs. House’s release from prison, the great migration of blacks to the North and West during and after World War I grew from a trickle to a stream. African Americans were drawn to economic opportunities made available because the war reduced European immigration and increased demands for workers in industry for military preparedness. About a half million African Americans left the South between 1916 and 1919, and nearly a million followed in the 1920s. In addition, within the South, many moved from rural areas to cities.

Mrs. House lived to witness the growth of South Nashville as thousands of African-American sharecroppers and other rural blacks moved into the city, either permanently or as a way station on the trip north. The local African-American population grew by 25 percent to 42,836 in 1930. Many of these migrants moved into South Nashville, where Mrs. House lived, in neighborhoods blacks had developed since the Civil War. Former tenant farmers and sharecroppers without other occupational skills, the migrants worked in low-wage, unskilled jobs like their neighbors. African-American women maintained their overwhelming presence in the low-wage workforce. Well over half of the Nashville female black population worked mainly in domestic or personal service occupations or as washerwomen like Mrs. House. Only a small number of black women were professionally employed; 57 African-American women held jobs as teachers or doctors, or in insurance and real estate, with 526 working in some area of the clothing and textile sector. Those African Americans in the professional and business class lived nowhere near Callie House’s neighborhood.4

Black business in Nashville and elsewhere reached its peak in the favorable national economy of the 1920s. Black downtown, Cedar Street (now Charlotte), from Fourth to Tenth Avenue, boasted the two black banks, physician and law offices, churches, printing and publishing houses, retail stores, the colored YMCA, and the Negro Opera House.5

The business and professional institutions were led by a coterie of younger black lawyers, doctors, public school teachers, college professors, and businessmen, who emerged to pick up the mantle left by James Napier, Richard Boyd, and Preston Taylor. These emerging leaders belonged to the NAACP, made ending segregation a major goal, and also showed great interest in the culture and literature of the Harlem Renaissance. They supported the student strike against the white president of Fisk in 1925, which took energy and time. After the city sent in policemen to beat the student protestors, working-class black Nashvillians joined the protests. Some 2,500 local blacks attended a rally at St. John’s A.M.E. Church to support the students and roundly denounced police brutality. The college’s white trustees refused to give in to the students; it was not until 1946 that Charles S. Johnson became the first African-American president of Fisk. In this period as in the past, except for the protest against police abuse, the activities of bourgeois African Americans mostly bypassed Callie House and other working-class residents of Nashville.6

On June 6, 1928, Callie House died at age sixty-seven. Living at home and “keeping house,” she had been hemorrhaging from uterine cancer for almost six months. According to her physician, George M. Kendrick, who saw her daily, she had bled for a week. Although Dr. Kendrick and his partners treated patients whether they could pay or not, an operation for Mrs. House was thought either not useful or too expensive. Her funeral was handled by P. M. Ransom and A. Morris, undertakers, an African-American firm.7

Callie House lies buried in Mt. Ararat Cemetery, organized in 1869 by the Sons of Relief (No. 1) and the Colored Benevolent Society as the city’s first black cemetery. Mt. Ararat is a thousand feet north of the junction of Murfreesboro Pike and Elm Hill Pike, next to the still existing dairy. Although the property was later sold to Greenwood Cemetery owner Preston Taylor, a historic plaque marks the Mt. Ararat location, but there is no map of the burial sites and no record of where individuals’ graves are located. Among the graves many markers are worn away. My nephew and I have tramped the entire grounds repeatedly, vainly seeking a marker for Callie House.8

Mrs. House’s funeral most likely took place at the same church where services were later held for her brother, Charles Guy, who died in 1933. Charles, an itinerant Primitive Baptist preacher, like most among the denomination’s clergy, supported his family as a laborer.9

The funeral arrangements for Mrs. House’s brother were handled by the most flamboyant Primitive Baptist minister in Nashville, Reverend Zema W Hill, the charismatic pastor of Hill’s Tabernacle Primitive Baptist Church. Born in rural Franklin County, Hill joined a local church and became a preacher as a teenager. After he moved to Nashville in 1916, his “elegance, good looks and magnetic preaching style” quickly developed a large following. By 1919, he had started Hill’s Tabernacle and his funeral home. Unlike other black Primitive Baptist churches—“primitive” wood structures with potbellied stoves—Hill built his tabernacle of brick with two furnaces; congregants could look down through the registers and see the coals burning. His congregation of washerwomen, domestics, and laborers contributed their mites. Hill’s “civic minded zeal” led him to arrange funerals for the destitute where he would pass a plate in a “silver service” to collect contributions from the congregation. His new funeral home, with six-foot concrete polar bears at the entrance, and his fleet of automobiles, with his name in gold letters, attracted attention and more customers.10

White and black civic and political leaders attended the church services, sitting among the working-class congregation. When she arrived in Nashville “from the country” in the early 1930s, my mother, Frances Southall Berry, joined Hill’s Tabernacle. My brother and I attended services there while we lived in the neighborhood with my mother’s eldest sister, Aunt Ever-leaner, and her family. The famous and the infamous showed up at Hill’s Sunday services, including my uncles—my mother’s brothers—inveterate sinners who drank and partied when not at work but would not have missed Reverend Hill’s church services on Sunday. My uncles used to tease my mother, saying that before Zema Hill even said anything, excited women threw their pocketbooks at him. During services those who could not squeeze inside the building stood or sat outside in good weather. In a period before air-conditioning, the congregation fanned itself with paper fans advertising local businesses as they sweltered in summer, and those outside poked their heads through the wide-open windows to see the spectacle.11

After her death, Mrs. House’s family can be traced through the city directories for the next few years. In 1929, the House family still lived at 1307 10th Avenue South, while her brother, Charles Guy, and his family remained nearby. Guy worked as a laborer until his death, and Mrs. House’s younger son, William, worked as a clothes cleaner at a shop on Fourth Avenue North downtown. In 1929, Thomas, Mrs. House’s eldest son, pressed clothes at the Just Rite Tailor Shop; William’s wife worked as a domestic, and Charles’s wife took in laundry.

In 1933, Callie House’s daughter Annie rented a place on Vernon Street, where Callie and Charles and their families had first rented rooms in Nashville when Mrs. House began taking in washing. In the same year, William’s wife was working as a maid at the James Robertson Hotel. Annie worked as a maid and Ross as a houseman. Thomas lived on Vernon Street also, with Annie and Ross, probably her son. The 1957 directory recorded their names as Howse. However, when Mrs. House’s daughter Mattie died in 1971, her last name was recorded as House in the official city death records.12

Howse was the most popular spelling of the House name in Nashville. A white Howse family, including Mayor Hilary Howse and his relatives, had owned slaves. Like many African Americans, descendants of the Howses kept the name. Hilary Ewing House, born into a slaveholding Rutherford County family in 1866, served as mayor of Nashville from 1909 to 1915 and again from 1924 to 1938. The African-American Howses and the few Houses who live in Nashville today claim to know nothing about Callie House.13

Even though Mrs. House appears to have stopped working in the reparations movement after her imprisonment, some of the local chapters of the Ex-Slave Association continued their self-help activities in the ensuing years. The Atlanta council, led by Professor Brunsey R. Holmes, president of the Holmes Institute, held fund-raising drives to provide mutual assistance for the old ex-slaves in the form of “Warm clothing and something good to eat.” The affiliate repeatedly asked the public to send groceries, old clothes, or money and held “tag days” (yard sales) to raise funds. Two of Holmes’s female relatives, Savannah and Kizza, taught at the school where Professor Holmes served as the principal. The Atlanta Constitution published a photograph of “Holmes of The Ex-Slave Association,” which apparently gave weekly allowances for fuel, groceries, and clothing to old ex-slaves right before Christmas. The chapter, organized in the early 1900s, engaged in such self-help activities as late as 1931.14

Although the federal government defeated the legislative goals of the Association, the hope for and belief in pensions on the part of old ex-slaves remained alive. Their children and grandchildren also remembered the demand. In April 1928, some relatives of a freedman in Wetumka, Oklahoma, asked the U.S. attorney general, “Is there any money set aside for old ex-slaves by the U.S. Government?” An Arkansas freedman asked in December 1930, “Had there Ben a law in Congress that we people should draw a pension by being own by southern people?”15

Even after Callie House’s jailing and death, old ex-slaves like these kept writing the government to demand pensions for their bondage and forced labor. Sarah Graves, Edgar and Minerva Bendy, Tiney Shaw, and Molly Ammond.

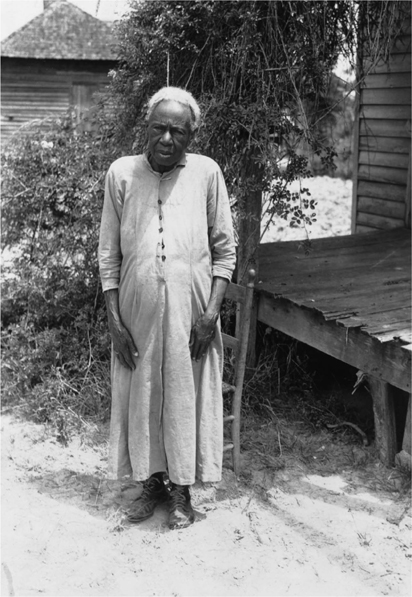

Some of the local chapters continued to work after Callie House’s jailing. This Atlanta chapter lasted at least until 1932. Brunsey R. Holmes, their president, is shown giving funds to the needy.

A freedwoman in Holmes County, Mississippi, wrote to President Herbert Hoover, wanting to know if the pension bill had ever been passed. She “were a girl the age of 16 when freeman [freedom] were taken place and now am an old lady blind can’t see and if there ever were a person kneads assistance I know its me. My owners in slavery were Mr. Jeff Poole who lived in Moreland, Miss.”16

In 1934, a number of old ex-slaves wrote President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Is there any way to consider the old slaves?” One asked specifically, whatever happened to the idea of “giving us pensions in payment for our long days of servitude?” The government officials replied that no legislation existed. Their letters attest to the interest in pensions. They also affirm Callie House’s insistence during federal investigations and prosecution that she had told ex-slaves only that the association wanted to gain the enactment of a federal pension law. Members had not been told that Congress had passed a law.17

As late as 1937, the attorney Richard Broxton of New York City asked the Treasury Department and the attorney general whether the law prohibited “forming an Organization designed for the purpose of having the Government appropriate funds for the payment of the services of those held in involuntary servitude—such funds, if available, to be paid to the descendants of such ex-slaves, if located.” His inquiry and others concerning the legal issues received a standard response: “The Attorney General is authorized by law to give opinions only to the President and heads of the Executive Departments.”18

The interest of the ex-slaves and their descendants in pensions persisted. Callie House gave voice to their pleas and her “whole soul and body to the movement.” African Americans, who carried the message of the movement with them as they migrated out of the South, carried the struggle with them to live for another day.19

In the years since the demise of the Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association, scholarly analysis of social movements has shed additional light on the fate of the organization and Mrs. House. The “changes in the political environment” that a social movement confronts, rather than “the internal characteristics of the movement [’s] organization and the social base upon which it drew,” determine its success or failure, according to sociologist Charles Perrow and others. Perhaps reparations for African Americans will never become a reality, but the 1890s proved a decidedly negative time for the ex-slave pension movement. Mrs. House believed that the aging condition and social deprivation of the ex-slave population called for a remedy. Also, pensions had been given quite freely to white Union veterans, and even Confederate states paid pensions. However, most public attention to the unfinished business of the Civil War focused on achieving national reconciliation and reunion consensus, bringing closure to the divisions of whites North and South.20

By the time Mrs. House and her associates were working for ex-slave pensions, the Reconstruction-era interest in blacks and freedmen and-women had become a distant memory. So had the national refusal, in the immediate aftermath of emancipation, to give land or other property to the freedpeople to start them on their way. Except for praising loyal retainers, the “Mammies and Uncles,” of plantation lore, talking about slavery symbolized a refusal to forget and an offensive insistence on still waving the “Bloody Shirt” of civil war. The bloodiest war in American history, in which more than 400,000 soldiers laid down their lives, no longer was viewed as a war to save the Union that had become a war to free the slaves.21

Reconciliation and reunion between North and South focused on the broken bonds of brotherhood, not the travail of combat, much less the fate of the ex-slaves. Though poorly armed, clothed, and fed, and often denied their pay, black Union soldiers fought and died to save the Union and to earn freedom for themselves and other African Americans, yet the claims of more than 186,000 African Americans who served in the Union ranks went unacknowledged, banned from the national debate.22

President Abraham Lincoln’s words in the Gettysburg Address, delivered on November 19,1863, gave hope of reparations when he described the task before the nation as finishing the work so that those who died had not died in vain. He saw the goal as ensuring “that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom.” By war’s end, his meaning, described by Confederate officials as slavery and the South’s determination to preserve it, had been accepted by millions of northern whites and almost all African Americans. The Lincolnian idea that Emancipation would result in a new birth of freedom, in a reunited nation, and a new charter of equal rights in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution, receded in the face of a new national disposition. Those who wanted to cite Lincoln’s sentiments and reject any measures beyond emancipation for African Americans could cite the president’s second inaugural address, in which he seemed to equate the sacrifice of battle with reparations for enslavement. Lincoln said he hoped the war would end quickly but God might will that “it continue until all the wealth piled up by the bondsman’s two hundred years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn by the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago.”23

As historians Nina Silber and David Blight explain, the custodians of Confederate memory won a postwar battle to celebrate the South’s lost cause as a valiant crusade for constitutional liberties and states’ rights that lost only to brute force. In this version of history, slavery had little to do with causing the war, and reconciliation of the two sections that had fought a “brother’s war” deserved concentrated attention instead of discussing the consequences of abolition.24

In 1888, only four years after he had pleaded for a memory of abolition among causes and consequences of the Civil War, Albion Tourgee, the white Massachusetts lawyer who had gone south to serve as a judge after the war, conceded defeat. In the “field of American fiction today,” he wrote, “the Confederate soldier is the popular hero. Our literature has become not only Southern in type, but distinctly Confederate in sympathy.”25

With sad inevitability, forces that emphasized reconciliation and those with white supremacist visions merged to overwhelm any “New Birth of Freedom” in the future of African Americans. By 1913, “a combination of white supremacist and reconciliationist memories had conquered all others,” according to Blight. In that year, the fiftieth anniversary commemoration of Gettysburg attracted five thousand aging veterans and many more spectators, and took place, Blight notes, “as a national ritual in which the ghost of slavery, the very questions of cause and consequence, might be exorcized once and for all, and an epic conflict among whites elevated into national mythology.” In such a climate, redress for the defeated white southerners, not reparations for African Americans, became a more acceptable objective. Whites in the North and South sought to heal the harm they had done to each other.26

Essentially, the view of the Civil War and Reconstruction portrayed in D. W Griffith’s 1915 movie Birth of a Nation, which demonized African Americans and depicted white southerners as victims, prevailed throughout the country. Based on Thomas Dixon’s The Clansman, a novel about Reconstruction that appeared in 1905, Birth of a Nation told a story of how heroic whites had redeemed the South from efforts to Africanize it by black brutes unleashed by the abolition of slavery. The movie faithfully followed the book. The movie was the first motion picture to be shown at the White House. The southern segregationist president Woodrow Wilson called the film “like writing history with lightning.” Meanwhile, as the newly founded National Association for the Advancement of Colored People protested unsuccessfully against the film’s showing, millions of people saw it and forever viewed themselves and the country in the context of the film’s contrived political appeals.27

Reflecting the growth of a general southern nostalgic movement, there was some sentiment for establishing monuments and memorials to the “old black mammies, “and some Confederate veterans endorsed the idea of pensions to reward those slaves who “peaceably cultivated the plantations of their masters” during their absence and showed absolute “fidelity.” But even their efforts were of no avail.28

In such a climate, the adoption of legal and practical racial segregation was not surprising. After the Civil War and Emancipation, and through the years of reconciliation and reunion, African Americans attempted to gain political and economic opportunity through various strategies, and a few people became relatively prosperous. However, African Americans’ freedom did not bring economic, political, or social equality. In an effort to gain fair treatment and opportunity, some joined political protest groups such as the African American League, the Niagara Movement, and later the NAACP. Others boycotted segregated streetcars and struck against unequal wages. Some African-American factions placed more emphasis on self-help through mutual assistance, racial solidarity, emigration, and separatism. Still, the situation was so bad that the usually optimistic Frederick Douglass, who lived through this period of transformation in thought with its reshaping of memory and the forgotten aims of the Civil War, doubted aloud in the 1890s whether American justice and equality of rights would ever apply fully to African Americans.29

Despite the prevailing national mood and the powerful forces that fought her efforts, Callie House insisted that the nation acknowledge its debt to every old ex-slave. In the end, she paid dearly for her stubborn devotion to the cause.