IN THE YEARS BEFORE THE Hitler regime, Germany was home to one of the strongest and most militant left-wing movements in Europe, firmly based in the country’s large and well organized working class. The years after World War I saw insurrections in Bavaria and the Ruhr region, and had it not been for errors and betrayals on the left, many still believe that communist revolution in Germany could have succeeded in giving birth to a radically different twentieth century.

That, of course, is not what happened, and as events unfolded the left that had impressed generations of European socialists was decimated by the rise of German fascism, forced into exile, reduced to inactivity, or sent off to the camps.

When the organized institutions of the left reappeared in the postwar period, they were incapable of overcoming their own historical weaknesses, weaknesses that were actively reinforced by the Allies’ corrupt and repressive policies. Those few independent antifascist groups which had formed in the last days of the war quickly found themselves banned, unwelcome intruders on the victors’ plans, this Allied suppression of any autonomous workers’ or antifascist revolt constituting the flipside to the charade of denazification.

The eclipse of any authentic left-wing opposition continued in the years following the division of Germany. The Christian Democratic Union, the concrete expression of the alliance between the German ruling class and American imperialism, experienced little in the way of opposition as it helped implement the Marshall Plan and establish the legal machinery with which to fight any resurgence of left-wing militancy.

Yet, while the political aspects of the Marshall Plan were carried out with little difficulty, the rearming of West Germany, not surprisingly when one considers the outcome of both World Wars, met with intense opposition.

In the immediate postwar period, West Germans were overwhelmingly opposed to rearmament. By 1952, this sentiment had coalesced into a broad movement, including the not-yet-banned KPD, trade unions, socialist youth groups, Protestant church groups,1 pacifists, and, at times, sections of the SPD. This progressive alliance was flanked on its right by small numbers of nationalists and even fascists who objected to the way in which rearmament would anchor the country in the western bloc.2 Despite this, the “Without Us Movement” (as it was known) was a predominantly left-wing amalgam. It was the first large protest movement in the new Federal Republic,3 and while it may appear timid and ineffectual in retrospect, it represented a real break in the postwar consensus at the time.

The response from the Adenauer regime revealed the limits of CDU democracy: in 1951, a KPD referendum initiative on the question was banned, as according to the Basic Law only the federal government was empowered to call a plebiscite. The Communists decided to go ahead anyway, polling people on street corners, through newspaper questionnaires, and at popular meeting places. The “referendum” was more agit prop than a scientific study; at one movie cinema in the town of Celle, for instance, there is a report that just as the feature film ended an eager pollster asked everyone opposed to rearmament to stand up—100% opposition was recorded. Little surprise that the KPD eventually found that almost six million West Germans had “registered” their opposition to the government’s plans.4

Suffice it to say that Adenauer was not amused, and polling people soon became a risky endeavor: there were a total of 7,331 arrests, and the KPD Free German Youth front group was banned simply for engaging in what amounted to a glorified petition campaign.5

At the same time, as if to make matters crystal clear, on May 11, 1952, a peace rally in the city of Essen was attacked by police, at first with dogs and clubs, and then with live ammunition. Philipp Müller, a member of Free German Youth, became the first person to be killed in a demonstration in the new Federal Republic. As a sign of things to come, no police officer would ever face charges for Müller’s death, but eleven demonstrators were subsequently jailed for a total of six years and four months for disorderly conduct and “crimes of treason against the Constitution.”6

Philipp Müller, April 5, 1931-May 11, 1952

Not that repression was the only tool against incipient revolt: misdirection also remained an important weapon in the ruling class arsenal. Throughout 1953, there were almost one hundred strikes at different factories to protest against the CDU’s rearmament policies. As the politicized sections of the working class were moving aggressively against Adenauer’s plans, the SPD and trade union leadership lined up to rein things in. All energy was now funneled into one big rally in Frankfurt. However, the initiative was removed from the rank and file, and in the end the rally was simply used to drum up support for the SPD.1 As the CDU moved ahead regardless, the Social Democrats withdrew organizational support, and the movement (now robbed of any autonomous basis) dissipated almost immediately.2

With its most steadfast opponents kept in disarray by their “leaders,” the Adenauer regime easily ratified rearmament through the Treaty of Paris in 1954. The next few years saw the establishment of voluntary military service, universal male conscription, and the production of war materials, further sealing the ties between big business and the state. Demoralized by their failure to prevent any of this, the opposition began to melt, a 1955 poll finding that almost two thirds of the population now considered remilitarization to be a “political necessity.”3

For the CDU, rearmament, like the Basic Law, was simply part of the Federal Republic acquiring the powers of a “normal” state, part of West Germany’s integration into the imperialist bloc. While there were numerous such state powers bestowed during this period, one which will bear some relevance to our study is the 1951 establishment of the Bundesgrenzschutz, the Federal Border Guard, also known as the BGS. Under the jurisdiction of the Federal Ministry of the Interior, the BGS was initially a paramilitary force of 10,000, its activity restricted “to the border area ‘to a depth of thirty kilometres.”4

In 1951, most leftists had feared that the BGS was a roundabout way to establish a standing army. As we have seen, such a ploy did not prove necessary (although many border guards would be integrated into the new armed forces). Rather, the Border Guard would eventually serve as the basis for a national semi-militarized police force.

Despite these discouraging beginnings, antimilitary sentiment remained high, and when, in 1956, the Adenauer government responded favorably to a U.S. “offer” of tactical nuclear weapons, this set off a series of spontaneous mobilizations across the country. In 1957, members of West Germany’s second largest union, the Public Service, Transport, and Communication Union (ÖTV) voted 94.9% in favor of a strike against nuclear armament, a call which was echoed by the president of the powerful IG Metall trade union. In Hannover, 40,000 people demonstrated against nuclear arms, while in Munich there was a turnout of 80,000, and in Hamburg 120,000 people took to the streets.5 Opinion polls showed 52% of the population supporting an antinuclear general strike.

The SPD and trade union brass moved to quash this mass movement, which was spinning out of control, by redirecting the campaign away from the streets and factories and into the ballot boxes, proposing a referendum instead of a general strike. Predictably, the government challenged this referendum proposal before the Constitutional Court, where it was ruled unconstitutional in 1958.

The ploy worked, the momentum was broken, and the antinuclear weapons movement entered a period of sharp decline. For years to come, its only visible legacy would be the annual peace demonstrations held every Easter Weekend, the so-called Easter Marches.

Of great relevance to the future history of the West German left, and our story in particular, an important counterpoint to the disreputable machinations of the SPD emerged from its own youth wing: the Socialist German Student Union (SDS).

The SDS had been founded in 1946 as a training ground from which to groom the future party elite (Helmut Schmidt, West Germany’s future Chancellor, was the group’s first president). In the context of the anti-rearmament movement, though, a shift began to occur, and at its 1958 conference, the leadership of the SDS was won by elements significantly to the left of the SPD:

Their main interest was in the development of socialist policies and, in particular, they wanted to build the campaign against nuclear weapons, a campaign which the SPD had already deserted. The resolutions of the SDS conference were a “declaration of war” on the SPD leadership. The SDS first of all developed an anti-imperialist position and demanded the right of national self-determination for the Algerians and the withdrawal of French colonial troops. After this there were congresses against nuclear weapons, for democracy and in opposition to militarism. The SPD strongly condemned this development.6

In May of 1960, to counter this leftwards drift, students loyal to the SPD leadership formed the Social Democratic Student Union (SHB). This move by the right was answered in October 1961 by SPD left wingers forming the Society for the Promotion of Socialism (SF). Unable to neutralize this growing left-wing revolt, the SPD leadership decided to do what it could to isolate it, purging the SF and SDS in a move which completed the alienation of the critical intelligentsia and youth from the party for years to come. (Ironically, the SHB itself continued to be pulled to the left, forced to tail positions staked out by the SDS, until it too would find itself expelled in the 1970s.)1

Things were brewing beneath the surface, and a new generation was finding itself increasingly miserable within the suffocating and conservative Modell Deutschland. American expatriate Paul Hockenos describes the fifties cultural climate that surrounded these young people:

Corporal punishment in schools… was still routine, and at universities students could be expelled for interrupting a lecture. The Federal Republic still had “coupling laws” on the books that forbade single men and women under twenty-one to spend the night together—or even to spend time together unchaperoned. Parents who allowed their children to stray could face legal penalties. In contrast to the GDR’s school curricula, in which the churches had no say, in the West German schools there weren’t sexual-education programs until the 1960s.2

In the words of Detlev Claussen, who would later participate in his generation’s revolt, “They try to make it look better than it was but it really was that bad! It was a terrible, terrible time to grow up.”1

Another indication of what life was like in the post-genocidal society came in the winter of 1959-60, as a wave of antisemitic graffiti and attacks on Jewish cemeteries swept over the country. This prompted some Frankfurt School sociologists to carry out a study which revealed that behind an apathetic 41% who remained indifferent, a hardcore 16% of the population was openly antisemitic, supportive of the death penalty (banned under the Basic Law) and expressing “an excessive inclination for authority.”2

One of the projects most responsible for challenging this reactionary and stultifying culture was the magazine konkret, published in Hamburg by Klaus Rainer Röhl. An increasingly important forum for progressive youth who rejected the CDU consensus and the country’s conservative cultural mores, the magazine was widely read within the SDS. As Karin Bauer notes, “the magazine thrived from the happy union of intellectual, aesthetic, and popular appeal…”3 Decidedly political, “Recurrent themes were Cuba, anticolonialism, German fascism, the antinuclear struggle, human rights, and social justice.”4

Unbeknownst to its public, konkret was actually funded and in part controlled by one of the remaining clandestine KPD cells which had gone into exile in East Germany.5 The magazine’s chief editor was Röhl’s wife, a woman who had been active in the SDS since 1957, and had secretly joined the illegal KPD in 1959. Her name was Ulrike Meinhof.

Another radicalizing event for many young people at the time was the Auschwitz trials, held in Frankfurt between 1963 and 1965. Largely a propaganda exercise to cover up the far greater number of Nazis who had found their way into the new West German establishment, twenty-two former SS-men and one Kapo were tried for murder or complicity in murder. Regardless of the hypocritical aspect of the trial, the fact that for two and a half years almost three hundred witnesses came and testified, and had their testimony reported in the media, gave an inkling of what Auschwitz meant to a generation of German youth, who—quite understandably—now saw their teachers, civic leaders, and even their parents in a horrible new light.

These trials, and the general “discovery” of the Holocaust, were a radicalizing event for many young people at that time;6 as one veteran of the New Left would later recall:

That the Germans could kill millions of human beings just because they had a different faith was utterly inexplicable to me. My whole moral world view shattered, got entwined with a rigorous rejection of my parents and school. If religion had not prevented this mass destruction of human beings, then it is no good for anything, then the whole talk of love of your neighbor and of meekness... was just a lie.7

Despite what in retrospect may seem to have been a growing potential for revolt, during these early years, the SDS was silent, turned inward, engaging in “seminar Marxism” as it found its bearings outside of the SPD and struggled to elaborate a consistent analysis and strategy. When it did return to the public arena, it was as a small, consciously antiimperialist organization influenced by the experiences of China, Cuba, Algeria, and Vietnam, advancing the analysis that “liberation movements in the Third World, marginal groups in society, and socialist intellectuals now constituted the revolutionary subject in society and the appropriate strategy was direct action.”8 (It is worth noting that the German Democratic Republic was pointedly not one of the ideological reference points for the new SDS.)

A line was crossed when Moise Tschombe visited Berlin in December 1964. To the applause of the West German ruling class, and with the help of German mercenaries, Tschombe had led a bloody, anticommunist secession in the Congolese province of Katanga. He was considered responsible for the 1961 murder of Patrice Lumumba, the first president of the Congo and a beloved symbol of the anticolonial struggle in Africa.

Hundreds of protesters turned out against Tschombe, and when the police tried to clear them away, they fought back in what would later be described as the starting point of the antiauthoritarian revolt in West Germany.1

The SDS played a prominent part in this protest. Based on university campuses, it was becoming the most important organization in the growing and increasingly militant protest movement against imperialist domination of the global South, most especially against the war in Indochina. Demonstrations ceased to be the timid rituals they had been; for the first time in decades, student protests escalated into street fighting.

1964 was also a year of change for konkret. The communist world was at the time deeply divided by the falling out between the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. Over the years, this split would only become more bitter until each side came to see the other as being objectively as bad as—or even worse than!—the imperialism represented by the United States. Despite its ties to the KPD, konkret was taking an increasingly pro-Chinese line, going so far as to support China’s acquiring nuclear weapons. At this, its East German patrons lost patience, and after failing to browbeat Meinhof into submission at a secret meeting in East Berlin, they cut off all funding.2 In their turn, Meinhof and Röhl resigned from the KPD. As a solution to this new lack of money, Röhl made drastic changes to the magazine’s presentation, turning it into a glossy publication which now featured scantilyclad women in every issue—its circulation almost tripled.3

Far from suffering as a result of their separation from the SPD, the SDS, konkret, and others on the left were now particularly well placed to benefit from a series of economic and political developments, even though these were not of their doing and lay well beyond their control.

In 1966-67, a recession throughout the capitalist world pushed unemployment in the FRG to over a million for the first time in the postwar era, a situation the ruling class attempted to exploit to tip the balance of power even further in its favor. As Karl Heinz Roth explains:

Threats of job losses and elimination of all the groups of workers who would have been able to initiate advanced forms of struggle laid the basis for a general anti-worker offensive.4

Furthermore:

The bosses freely admitted that they were using the crisis to intensify work conditions amongst all layers of the global working class. From their point of view, the temporary investment strike was necessary to create the basis for a recovery through a “cleansing of the personnel.” Three hundred thousand immigrant workers and almost as many German workers were thrown out into the street.5

In a move to consolidate support amongst more privileged German workers and thus exploit the divisions within the proletariat, the SPD was brought into a so-called “Grand Coalition” government alongside the Christian Democratic Union and Christian Social Union. This created a situation in which former resistance fighter and SPD chief Willy Brandt was now vice-chancellor alongside former Nazi Georg Kiesinger of the CDU, and the CSU’s far-right Franz Josef Strauγ was Minister of Finance alongside the SPD’s young luminary, Karl Schiller, who held the Economics portfolio.

The SPD was completely discredited by its open embrace of these reactionaries, and it now appeared that any real change could only come about outside of government channels. Disenchantment struck at West Germany’s youth in the universities, in the factories and on the street, as younger workers were increasingly marginalized by the new corporatist compact. The AuΕerparlamentarische Opposition (APO), or Extra-Parliamentary Opposition, was born.

The revolt was focused in West Berlin, an enclave that was a threehour drive into East Germany, and which remained officially under western Allied occupation, and so enjoyed the bizarre status of being a de facto part of the Federal Republic even though it remained legally distinct.6 In a sense, West Berlin afforded the personal freedoms of the capitalist west while its odd diplomatic status provided its residents with extra room to maneuver outside of the west’s constraints.1 This had many important consequences, not the least of which was that young men who moved to West Berlin could avoid the draft, as they were technically living outside of the FRG.

Not surprisingly, the city became a magnet for the radicals and counterculture rebels of the new generation. In the words of one woman who lived there, it was “a self-contained area where political developments of all kinds… become evident much earlier than elsewhere and much more sharply, as if they were under a magnifying glass.”2

Thus, it was in West Berlin that a group of students, gathered around Hans-Jürgen Krahl and the East German refugees Rudi Dutschke and Bernd Rabehl, began questioning not only the economic system, but the very nature of society itself. The structure of the family, the factory, and the school system were all challenged as these young rebels mixed the style of the hippy counterculture with ideas drawn from the Frankfurt School’s brand of Marxism.

Andreas Baader, Dorothea Ridder and Rainer Langhans, dancing in the streets of West Berlin (August, 1967)

Communes and housing associations sprung up. Women challenged the male leadership and orientation within the SDS and the APO, setting up daycares, women’s caucuses, women’s centers, and women-only communes. The broader counterculture, rockers, artists, and members of the drug scene rallied to the emerging political insurgency. Protests encompassed traditional demonstrations as well as sit-ins, teach-ins, and happenings. So called “Republican Clubs” spread out to virtually every town and city as centers for discussion and organizing, bridging the divide between the younger radicals and veterans of the earlier peace movements.

As one historian has put it:

Everywhere it could, the 1960s generation countered the German petit bourgeois ethic with its antithesis, as they interpreted it: prudery with free love, nationalism with internationalism, the nuclear family with communes, provincialism with Third World solidarity, obedience to the law with civil disobedience, tradition with wide-open experimentation, servility with in-your-face activism.3

Or, as one former SDS member would recall, it was a time when “everything”—hash, politics, sex, and Vietnam—“all seemed to hang together with everything else.”4

Despite its growing popularity on campus and amongst hipsters, this new radical youth movement was not embraced by the population at large, and demonstrations would often be heckled or even attacked by onlookers. This widespread hostility was a green light for state repression, with results which would soon become clear for all to see.

On June 2, 1967, thousands of people turned out to demonstrate outside the German Opera against a visit by the Shah of Iran, whose brutal regime was a key American ally in the Middle East. Many wore paper masks in the likeness of the Shah and his wife; these had been printed up by Rainer Langhans and Holger Meins of the K.1 commune,5 “So the police couldn’t recognize us [and so] they only saw the face of the one they were protecting.”6 Thus adorned, the protesters greeted the Iranian monarch and his wife with volleys of rotten tomatoes and shouts of “Murderer!”

(As Ulrike Meinhof would later write in konkret: “the students who befouled the Shah did not act on their own behalf, but rather on behalf of the Persian peasants who are in no position to resist under present circumstances, and the tomatoes could only be symbols for better projectiles…”)1

The June 2 rally would be a turning point, as the protesters were brutally set upon by the police and SAVAK, the Iranian secret service. Many fought back, and the demonstration is reported to have “descended into the most violent battle between protesters and police so far in the postwar period… It was only around 12:30 am that the fighting came to an end, by which time 44 demonstrators had been arrested, and the same number of people had been injured, including 20 police officers.”2

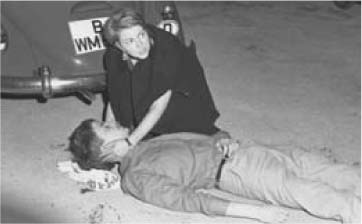

Most tragically, a young member of the Evangelical Student Association, Benno Ohnesorg, attending his first demonstration, was shot in the back of the head by Karl-Heinz Kurras, a plainclothes police officer with the Red Squad. Even after Ohnesorg was finally picked up by an ambulance, it was another forty minutes before he was brought to a hospital. He died of his wounds that night.

Benno Ohnesorg, shot by police, lies dying in the arms of fellow student Fredericke Dollinger.

This police murder was a defining event, electrifying the student movement and pushing it in a far more militant direction. It has been estimated that between 100,000 and 200,000 students took part in demonstrations across the country in the days immediately following Ohnesorg’s death. For many, especially those outside of West Berlin, it was their first political protest. As has been noted elsewhere, “Although two-thirds of students in the period before the shooting declared themselves to be apolitical, in the immediate aftermath of the shooting a survey found that 65 per cent of students had been politicized by Ohnesorg’s death.”3

The murder catapulted the SDS into the center of student politics across the Federal Republic. As one student activist later recalled years later:

The SDS didn’t have more than a few hundred members nationwide… and then all at once there was such a huge deluge that we couldn’t cope. Our offices were overrun. So we just opened SDS up and decentralized everything. We let people in different cities and towns organize themselves into autonomous project groups and then we’d all meet at regular congresses to thrash things out. More or less by chance it turned out to be an incredible experiment in participatory democracy.4

Initially, the state and the newspapers owned by reactionary press magnate Axel Springer5 tried to justify this murder, repeating lies that the protesters had had plans to kill police and that Kurras had shot in self-defense. Springer’s Bild Zeitung ominously warned that “A young man died in Berlin, victim of the riots instigated by political hooligans who call themselves demonstrators. Riots aren’t enough anymore. They want to see blood. They wave the red flag and they mean it. This is where democratic tolerance stops.”1

On June 3, the Berlin Senate banned demonstrations in the city—twenty-five year old Gudrun Ensslin was one of eight protesters arrested for defying this ban the next day2—and the chief of police Duensing proudly explained his tactics as those he would use when confronted with a smelly sausage: “The left end stinks [so] we had to cut into the middle to take off the end.”3 As for the Shah, he tried to reassure the Mayor of Berlin Heinrich Albertz, telling him not to think too much of it, “these things happen every day in Iran…”4

Nevertheless, given the widespread sense of outrage and the increasing evidence that Ohnesorg had been killed without provocation, Duensing was forced out of his job, and Senator for Internal Affairs Büsch and Mayor Albertz were eventually made to follow suit.

If June 2 has been pointed to as the “coming out” of the West German New Left mass student phenomenon, the international circumstances in which this occurred were not without significance. Just three days after Ohnesorg’s murder, West Germany’s ally Israel attacked Egypt, and quickly destroyed its army—as well as Jordanian and Syrian forces—in what became known as the Six Day War.

In the FRG, the Six Day War provided the odd occasion for a broadbased, mass celebration of militarism. To some observers, it suddenly seemed as if the same emotions and social forces that had supported German fascism were now expressing themselves through support for the Israeli aggressors, described (approvingly) as the “Prussians of the Middle East.”5 Although the SDS was already pro-Palestinian, most leftists had previously harbored sympathies for the Jewish state. The 1967 war put a definite end to this, establishing the New Left’s anti-Zionist orientation; as an unfortunate side effect of this turn, it also discouraged attempts to grapple with the gravity of Germany’s antisemitic past from a radical, anticapitalist point of view. (For more on Germany’s relationship to Israel, see Appendix III—The FRG and the State of Israel, pages 550-553.)

An uneasy calm reigned in the wake of the June 2 tragedy, and yet the movement continued to grow. More radical ideas were gaining currency, and at an SDS conference in September Rudi Dutschke and Hans-Jürgen Krahl went so far as to broach the possibility of the left fielding an urban guerilla. This was the first time such an idea had been mentioned in the SDS or the APO, and for the time being, such talk remained a matter of abstract conjecture.

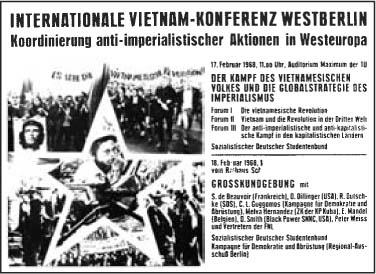

On February 17 and 18, 1968, the movement reached what was perhaps its peak when 5,000 people attended the International Congress on Vietnam in West Berlin, including representatives of anti-imperialist movements from around the world. Addressing those present, Dutschke called for a “long march through the institutions,” a phrase with which his name is today firmly associated.6 (By this, the student leader did not mean joining the system, but rather setting up counterinstitutions while identifying dissatisfied elements within the establishment that might be won over or subverted.)7 The congress closed with a demonstration of more than 12,000 people, and would be remembered years later as an important breakthrough for the entire European left.1

The establishment mounted its response on February 21, as the West Berlin Senate, the Federation of Trade Unions, and the Springer Press called for a mass demonstration against the student movement and in support of the U.S. war against Vietnam. Eighty thousand people attended, many carrying signs reading “Rudi Dutschke: Public Enemy Number One” and “Berlin Must Not Become Saigon.”

Increasing polarization was leading to a definitive explosion: less than one year after Ohnesorg’s murder, another violent attack on the left served as the spark.

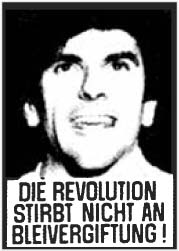

On April 11, 1968, Josef Bachmann, a young right-wing worker, shot Rudi Dutschke three times, once in the head, once in the jaw, and once in the chest. Dutschke, who was recognized as the leading intellectual in the SDS and the APO, had been the target of a massive anticommunist smear campaign in the media, particularly the Springer Press, which would be widely blamed for setting the stage for the attack. Indeed, Bachmann would later testify in this regard, saying, “I have taken my daily information from the Bild Zeitung.”2

The shooting occurred one week after Martin Luther King had been assassinated in the United States, and to many young German leftists, it appeared that their entire international movement was under attack. One young working-class rebel, like Dutschke a refugee from the East, summed up how he felt as follows:

Up to this point they had come with the little police clubs or Mr Kuras (sic) shot; but now it had started, with people being offed specifically. The general baiting had created a climate in which little pranks wouldn’t work anymore. Not when they’re going to liquidate you, regardless of what you do. Before I get transported to Auschwitz again, I’d rather shoot first, that’s clear now. If the gallows is smiling at you at the end anyway, then you can fight back beforehand.3

Bachmann had carried out his attack on the Thursday before Easter, and the annual peace demonstrations were quickly transformed into protests against the assassination attempt; it has been estimated that 300,000 people participated in the marches over the weekend, the largest figure achieved in West Germany in the 1960s.4 Universities were occupied across the country, and running battles with the police lasted for four days. “Springer Shot Too!” became a common slogan amongst radicals, and in many cities, the corporation was targeted with violent attacks. Thousands were arrested, hundreds were hospitalized, and two people (a journalist and a protester) were killed, most likely by police. On May 1, 50,000 people marched through West Berlin.

“The Revolution Won’t Die of Lead Poisoning”

Unprecedented numbers of working-class youth took part in these battles, with university students constituting only a minority of those arrested by police, a development that worried the ruling class.5

By the time it was over, there had been violent clashes in at least twenty cities. Springer property worth 250,000 DM (roughly $80,000) was damaged or destroyed, including over 100,000 dm worth of window panes.6

This rebellion and the police repression pushed many radicals’ thinking to an entirely new level. Bommi Baumann, for instance, credited the riots with opening his eyes to the possibility of armed struggle:

On the spot, I really got it, this concept of mass struggle-terrorism; this problem I had been thinking about for so long became clear to me then. The chance for a revolutionary movement lies in this: when a determined group is there simultaneously with the masses, supporting them through terror.7

Ulrike Meinhof was clearly thinking along similar lines, only she put her thoughts in print, sharing them with the public in a groundbreaking konkret article entitled “From Protest to Resistance.” Arguing that in the Easter riots “the boundaries between protest and resistance were exceeded,” she promised that “the paramilitary deployment of the police will be answered with paramilitary methods.”1

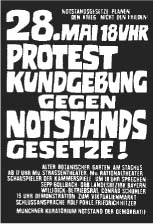

On May 31, the Bundestag passed the Notstandgesetze, or Emergency Powers Act, which besides providing the state with tools to deal with crises such as natural disasters or war, was also intended to open the movement up to greater intervention. The CDU had been trying to pass such repressive legislation for years, and short-circuiting opposition to it had been one of the advantages of forming a Grand Coalition along with the SPD. Coming as it did on the heels of the April violence, the legislation passed easily. (The fact that, just across the Rhine, France seemed also on the brink of revolution, enjoying its defining rebellion of the sixties, certainly didn’t hurt matters.)

Under the new Act, the Basic Law was amended to allow the state to tap phones and observe mail unhindered by previous stipulations requiring that the targeted individual be informed. Provisions were introduced in particular for the telephone surveillance of people suspected of preparing or committing “political crimes,” especially those governed by the catch-all §129 of the penal code, criminalizing the “formation or support of a criminal association.” The Emergency Powers Act also officially sanctioned the use of clandestine photography, “trackers” and Verfassungsschutz informants and provocateurs.

Throughout the month of May, as the Act was being passed into law, universities were occupied, students boycotted classes, and tens of thousands of people protested in demonstrations across the country, while a similar number of workers staged a one-day strike. To its critics, the Act represented a dangerous step along the road to re-establishing fascism in the Federal Republic, and this fear was simply reinforced by the way in which the Grand Coalition could pass the legislation regardless of the widespread protests against it.

Poster for a demonstration against the Emergency Powers Act, organized by the Munich Board for the Emergency Facing Democracy: “The Emergency Powers Act Plans for War, Not Peace!” Amongst those who gave closing speeches was one Rolf Pohle, at the time a law student prominent in the Munich APO.

Anti-Notstandgesetze activities were particularly impressive in Frankfurt, the financial capital of West Germany, which had also become something of an intellectual center for the student movement. On May 27, students occupied the Frankfurt University, and for several days held seminars and workshops addressing a variety of political questions. It took large scale police raids on May 30 to clear the campus.

All this notwithstanding, the Act was passed into law.

The failure of the anti-Notstandgesetze movement was experienced as a bitter defeat by the New Left. Many entertained alarmist fears that the laws would be used to institute a dictatorship, in much the same way as Hindenburg had used similar powers in 1930 and 1933 to create a government independent from parliament, which had facilitated the Nazi dictatorship. In the words of Hans-Jürgen Krahl:

Democracy in Germany is finished. Through concerted political activism we have to form a broad, militant base of resistance against these developments, which could well lead to war and concentration camps. Our struggle against the authoritarian state of today can prevent the fascism of tomorrow.2

In this heady climate, matters continued to escalate throughout 1968, sections of the movement graduating to more organized and militantly ambitious protests. The most impressive examples of this were probably those that accompanied attempts to disbar Horst Mahler.

Mahler was a superstar of the West Berlin left, known as the “hippy lawyer” who defended radicals in many of the most important cases of this period. He had been involved with the SDS, and was a co-founder of the West Berlin Republican Club and the Socialist Lawyers Collective.3 He had been arrested during the anti-Springer protests that April, and in what would prove to be a foolish move, the state had initiated proceedings to see him disbarred.4

Mahler’s case became a new lightning rod for the West Berlin left, which felt that the state was trying to muzzle their most committed legal defender. The student councils of the Free University and the Technical University called for protests the day of his hearing, one organizer describing the goal as “the destruction of the justice apparatus through massive demonstrations.”1

The street fighting which broke out on November 3 would go down in history as the “Battle of Tegeler Weg.”2 On the one side, the helmetwearing protesters (roughly 1,500) attacked with cobblestones and two-by-fours, on the other the police (numbering 1,000) used water cannons, tear gas, and billy clubs:

Several lawyers and bystanders were hit by cobblestones ripped from the sidewalks and hurled by the youths, most of them wearing crash helmets, as they moved forward in waves directed by leaders with megaphones.

Injured demonstrators were carried to waiting ambulances marked with blue crosses and staffed by girls wearing improvised nurses’ uniforms.3

Nor were the police spared. As another newspaper reported:

The demonstrators caused a heavy toll of police casualties with their guerrilla style of battle: thrusting at police, withdrawing, consolidating and then thrusting again from another angle.

At one stage they managed to beat back a 300-man police force a distance of 150 yards… Police counted 120 injured in their own ranks. Ten of them had to be treated at a hospital. A police spokesman said seven of 21 injured demonstrators were taken to a hospital. The number of arrests was placed at 46.4

That same night a horse was injured when several molotov cocktails were thrown into the police stable.5 It would later be suggested that this attack was the work of an agent provocateur by the name of Peter Urbach.6

The court declined to disbar Mahler. Within a few days, the firebrand lawyer was once again making headlines with his latest case: the defense of the young antifascist Beate Klarsfeld, who had smacked CDU Chancellor—and former Nazi—Kurt Georg Kiesinger, hitting him in the face.7 Mahler would eventually win Klarsfeld a suspended sentence, at which point he counter-sued Kiesinger on her behalf, arguing that the very fact that a former Nazi was Chancellor constituted an insult to his client.8

The Battle of Tegeler Weg was another milestone, representing a willingness to engage in organized violence the likes of which had not been seen for decades. This period also saw the first experiments with clandestine armed activities, a subject to which we will soon return.

Thus, we can see that even as the spectre of increased repression haunted sections of the militant left, there existed both the desire and the capacity to rise to the next level.

At the same time, however, other developments offered the tempting promise that change might come about in a more comfortable manner by backing down and working within the system.

In October, 1969, the Grand Coalition came to an end, and under the slogan “Let’s Dare More Democracy!” an SPD government (in coalition with the FDP) was elected. SPD leader Willy Brandt was now Chancellor, and FDP leader Walter Scheel became Foreign Minister. The largely symbolic post of president went to political old-timer Gustav Heinemann, widely considered one of the Federal Republic’s most liberal politicians, despite the fact that he had been the Grand Coalition’s SPD Minister of Justice.9

For the first time in its history, the Christian Democrats had lost control of the West German parliament.

The new SPD government announced a series of measures which partially fulfilled the students’ more “reasonable” demands: there were new diplomatic overtures to East Germany, it was made easier to be declared a conscientious objector, the age of consent and the legal voting age were lowered from twenty-one to eighteen, no fault divorce legislation was passed, and a series of reforms aimed to modernize and open up the stuffy, hierarchical German school system.

For many, it seemed like a brand new day.

At the same time, Brandt announced an “immediate program to modernize and intensify crime prevention,” which included:

strengthening of the Criminal Investigation Bureau, the modernization of its equipment and the extension of its powers, the re-equipping and reorganization of the Federal Border Guard as a Federal police force, together with the setting up of a “study group on the surveillance of foreigners” within the security services.1

Nevertheless, these measures would not affect most activists, and the government shift away from the anachronistic conservatism of the CDU helped confuse and siphon off less committed students, draining potential sources of support for the radical left. At the same time, the movement itself was beginning to fragment.

Problems of male supremacy in the APO had become increasingly difficult to bear for radical women inspired by the feminist movements in the United States, France, and England. In September 1968, things had come to a head at an SDS conference in Frankfurt, where Hans-Jürgen Krahl found himself being pelted by tomatoes after he refused to address the question of chauvinism in the SDS. While many (but not all) of the women from the APO would continue to identify as being on the left, their political trajectory became increasingly separate, both as a result of dynamics internal to the women’s movement and of the continuing sexism outside of it.

The decline of the APO also occurred alongside renewed attempts to build various workers’ parties in line with the “correct” Marxist analysis. In 1968, the banned KPD (“Communist Party of Germany”) had been re-established under a new name as the DKP (“German Communist Party”), but boasting the same program and leadership. To most young radicals, though, this “new” Communist Party was of little interest, not only because of its association with the clearly unattractive East German regime, but also because of what was seen as its unimpressive and timid track record in the years before Adenauer had had it banned.

The different tendencies to emerge from the APO tapped into different aesthetic traditions—above: a call-out from the radical magazine Agit 883 for a demonstration against the Vietnam War.

below: “Everybody Out to the Red May 1st; Resist Wage Controls; Resist Wage Slavery; A United Working Class Front Against the Betrayal of the SPD Government”

Rather, there followed a veritable alphabet soup of Maoist parties, most of which were as virulently anti-Soviet as they were anti-American. These were joined by a much smaller number of Trotskyist organizations, and together all these would eventually become known as the “K-groups,” in a development roughly analogous to the New Communist Movement which developed at the same time in North America.

Those who remained to the left of the SPD while not joining any of these new party-oriented organizations included the sponti (“spontaneous”) left which had grown out of the APO’s antiauthoritarian camp, anarchists, and assorted independent socialists. Together, these were referred to as the “undogmatic left,” their bastions being the cities of Frankfurt, Munich, and—of course—West Berlin.

The movement continued to struggle, but with increasing difficulty, fragmenting in all directions, as the APO seemed to be coming apart at the seams.

In March 1970, following a chaotic congress at the Frankfurt Student Association Building, the SDS was dissolved by acclamation. In a brilliant ploy, two months later the government decreed an amnesty for protesters serving short sentences, thereby winning many of these middle class students back to the establishment. The student movement in West Germany was particularly vulnerable to this kind of recuperation, being overwhelmingly comprised of young people for whom there was a place in the more comfortable classes; in 1967, for instance, only 7% of West German students were from working class families (by comparison, in England the figure was almost one in three).1

Despite the APO’s inability to meet the challenges before it, one cannot deny that in just a few years it had thoroughly transformed West German society:

Among the consequences were the reform of education; a new Ostpolitik;2 the deconstruction of the authoritarian patriarchal relations in the family, school, factory and public service; the development of state planning in the economy; a greater integration of women into professional life and a reform in sexual legislation… the APO also provided the impetus to a socio-cultural break with the past. There was a very rapid change in social outlook and behavior patterns. The old ascetic behavior based on the notion of duty came to an end. Along with a different conception of social roles came a new set of sexual mores and a dissolution of the old respectful and subservient attitude towards the state and all forms of authority. There developed, in other words, a new culture which was to pave the way for the new social movements of the 1970s and 1980s.3