WHILE THE OVERWHELMING MAJORITY OF Germans never approved of the RAF or their declared strategy, there was a small but not insignificant base of support and sympathy for the guerilla amongst young people and the radical left.

Apart from the undeniable pleasure many felt at seeing certain targets physically attacked, there was widespread outrage at the brutal and seemingly excessive repression the state indulged in. Despite capture, the prisoners from the guerilla were managing to beat the odds and turn this repression to their advantage in a way that was consistent with their strategy of bringing out the violence inherent in the system.

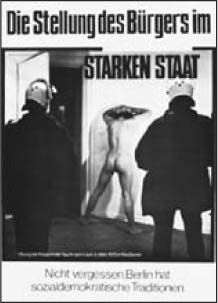

“The position of citizens in a powerful state—Don’t forget, Berlin has a Social Democratic tradition.” (Police action in West Berlin on the night of March 4/5, 1975)

Even before this strategy had won the new recruits who carried out the Stockholm action, countering this rise in sympathy had been designated a top priority for all sections of the political establishment. In the words of Interior Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher of the FDP, “The sympathizers are the water in which the guerilla swims: we must prevent them from finding that water.”1

Or as the CDU opposition leader Helmut Kohl put it, “We need to drain the swamp … in which the flowers of Baader-Meinhof have grown.”2

To this end, a variety of propaganda maneuvers, described by the prisoners as psychological warfare, combined with renewed efforts to isolate and neutralize those who were considered to be sympathizers and supporters, often through use of the Berufsverbot, §129, and specially crafted legislation. Such repression took on new dimensions under Siegfried Buback, who succeeded Ludwig Martin as Attorney General on May 31, 1974, just weeks after the SPD’s Helmut Schmidt replaced Willy Brandt as Chancellor. (Brandt had been forced to step down following a spy scandal known as the Guillaume Affair.)

The guerilla’s lawyers were among the first to be targeted.

On October 16, 1974, the Federal Supreme Court filed to seize defense correspondence between attorney Kurt Groenewold and the RAF prisoners, alleging that he and other lawyers were at the core of the prisoners’ communication network, known as Info. This move came in the midst of the third hunger strike, and constituted the first foray in the state’s newest offensive against the prisoners’ supporters.

Info was a system of prison communication devised with the help of lawyers from the Committees Against Torture, whereby messages would be passed between the prisoners. It represented a covert means of breaking through the isolation conditions, of maintaining group identity, sharing political opinions, and coordinating hunger strike activities. As we shall see, because it was so vital to the prisoners’ survival, it was severely repressed.

An explosion of rage and rebellion swept across West Germany following the death of Holger Meins in November 1974. On November 26, the state responded with Operation Winter Trip, which according to Attorney General Buback was specifically aimed at “the sympathizers’ scene,”3 both through direct repression and by preparing public opinion to accept new restrictions on civil liberties.

On December 13, the Attorney General filed to seize legal correspondence between the prisoners and defense attorneys Klaus Croissant and Hans-Christian Ströbele. Buback accused Croissant of belonging to a “criminal association” with his clients, a claim he based on Croissant’s use of the “terminology of left extremism, such as isolation torture, extermination conditions, brainwashing units, and the like.”4 Buback also pointed to Croissant’s public statements in support of the prisoners’ hunger strike and regarding the death of Holger Meins.

On December 30, Second Senate Judge Theodor Prinzing ruled that Croissant was indeed acting as “supporter” and “mouthpiece” for the prisoners and, as such, for a “criminal association.” Ströbele was also alleged to be a member of a criminal association for referring to himself as a “socialist and a political lawyer,” and for expressing “solidarity with the thinking of the prisoners,” whom he referred to as “comrades.”5

(Ströbele’s wife, Juliana Ströbele-Gregor, was for a time banned from her job as a schoolteacher, subject to the Berufsverbot due to her husband’s work on the prisoners’ behalf. Although she succeeded in forcing the Administrative Court in Berlin to withdraw the ban, she remained stigmatized as the wife of a “terrorist lawyer.”)6

On January 1, 1975, all of this was given added legal significance as legislation known as the Lex Baader-Meinhof, or “Baader-Meinhof Laws,” became constitutional amendments to the Basic Law. This solidified the attacks on the defense, §§138a-d allowing for the exclusion of any lawyers deemed to be “forming a criminal association with the defendant.” §231a and §231b allowed for trials to continue in the absence of a defendant if the reason for this absence was found to be of the defendant’s own doing—a stipulation directly aimed at the prisoners’ effective use of hunger strikes.7 Under §146, joint defenses were now prohibited, even though the Stammheim prisoners were facing a joint trial. This paragraph was used to forbid Otto Schily from speaking to those of the accused whom he was not defending, even when he saw them every day in court. Surveillance of defense correspondence was sanctioned by §148 and §148a, while the previously held right of the accused and defense lawyers to issue statements under §275a was withdrawn.1

On March 17, 1975, Prinzing approved Buback’s motion and Croissant was barred from representing Baader. The court listed three reasons for this decision. First, in November 1974, Croissant had refused to share information that the lawyers were circulating amongst the prisoners with his client Bernhard Braun because of Braun’s decision to break off his hunger strike. Second, Croissant had spoken at a solidarity event for the hunger strikers on November 8, 1974, the day before the death of Holger Meins. Third, Croissant had represented the prisoners in their negotiations with Spiegel regarding an interview conducted in January 1975.2

All three acts were deemed to constitute punishable offenses under §129.

On May 5, 1975, Groenewold was barred from representing Baader on the basis of allegations that his office served as an “information central” to allow prisoners to communicate between themselves. What this likely meant was that he had passed letters from one prisoner to another, and may have photocopied letters meant to be shared with several prisoners, all as part of the Info system.

The next day, on May 6, Ströbele was similarly excluded, again on the basis of accusations that he was key to an “information central.”

It is clear that this series of exclusions, as well as those that followed, were meant to serve several functions.

The most apparent objective was to prevent the prisoners from adequately defending themselves in the Stammheim trial which was about to begin on May 21.

Croissant argued that by facilitating the prisoners’ interview with Spiegel, and making public statements on their behalf, he was merely doing what any good lawyer was supposed to do: presenting his clients’ version of events and their motivations to the public. Yet, it would seem the prisoners were not supposed to have lawyers who did their job properly, for as Croissant observed, “By this court decision, just a few weeks before his trial, Andreas Baader is being denied a lawyer who has spent several years preparing his defense …”3

Indeed, as the pretrial hearing began, Baader no longer had a single attorney of his choosing.

These exclusions also served a second, and in some ways more insidious function. The prisoners had come to depend on their attorneys, and the role they played in facilitating communication. The lawyers’ visits and the Info communication system provided a form of human contact, a source of information regarding developments outside of the prison, and a modicum of political discussion.

As RAF prisoner Brigitte Mohnhaupt explained:

Info … was the only possibility—that is how we conceived of and understood it—the only possibility, in general, of social interaction between isolated prisoners. Even if it was only a surrogate for communication, only letters and paper, it was, nonetheless, the only option for discussion, for political discussion, for political information and, obviously, for orientation.

Such communication, besides constituting a basic human need, was also a form of resistance. Again, according to Mohnhaupt:

The sense of Info, its entire purpose, as we understood it, was as a means to resist isolation. We have said that every sentence that a prisoner writes in Info is like an act, every sentence is an action—that’s how it was for the prisoners.4

The state would allege that Info was used as a form of discipline between prisoners, by which the “ringleaders” coerced the others into participating in hunger strikes. There were also allegations that the prisoners used the system to communicate with active commandos on the outside, a claim which has never been substantiated. As Mohnhaupt explained, what seems far more likely is that Info was threatening precisely because it opened a hole in the brutal isolation conditions the government was attempting to perfect. By clamping down on the lawyers and putting an end to this contact, the courts were able to further isolate the prisoners.5

Finally, the vendetta against the lawyers can be seen as part of the state’s broader repressive approach intended to intimidate those who might stand with the guerilla. Groenewold was subjected to the Berufsverbot on June 121 and later that month, RAF lawyers found their offices and homes targeted as police carried out simultaneous raids in Hamburg, Heidelberg, Stuttgart, and West Berlin.

Over the next several years, the lawyers were repeatedly arrested and in some cases sentenced to considerable prison terms. They were openly followed by police; in some cases, agents were stationed outside their offices, taking photos of everyone, political or not, who entered.

On June 18, 1976, in a period of incredible tension in the movement, the office of Klaus Jürgen Langner, Margrit Schiller’s attorney, was firebombed; seven people on the premises were injured.2 Not long afterwards, Axel Azzola resigned his mandate, explaining that “In this trial, one cannot speak without fear, and without freedom of speech there can be no defense … I am terribly afraid.”3

These attacks on the lawyers came at the same time as a new volley of legislation, aimed at the entire radical left, was being passed through the legislature.

In the summer of 1976, §129a became law, a more intimidating subsection of §129 specifically related to “support for a terrorist organization”: the maximum penalty for “ringleaders” and “chief instigators” was increased to ten years.4 At the same time, civil rights protections were loosened so that mere suspicion that an individual was supporting a criminal organization, even where no criminal act had been committed, became sufficient grounds to issue search and arrest warrants.5

This came after §88a had been passed in January 1976, providing for a maximum three-year jail sentence for those who “produce, distribute, publicly display, and advertise materials that recommend unlawful acts—such as disturbing the peace in special (e.g. armed) cases, murder, manslaughter, robbery, extortion, arson, and the use of explosives.”6

It was not long before §88a was being used to prosecute not only radical newspapers which reprinted the guerilla’s communiqués, but also the bookstores which carried such publications. On August 18, the police carried out predawn raids on the homes of booksellers in seven cities, as well as ten bookstores and a book distribution center, confiscating many volumes that they deemed subversive.7

Beyond the legal chill, a variety of dirty tricks and lies were also used to try to undercut public sympathy for the guerilla.

False flag attacks like the ones threatened in Stuttgart in 1972 were now actually carried out, taking aim at random bystanders. A bomb placed in the Bremen Central Station in December 1974 injured five people. Then, in 1975, there was a spate of such attacks: on September 13, four people were hurt when a bomb went off in the Hamburg train station,8 claimed by a phantom “RAF Ralf Reinders Commando.”9 (The next day, a fake bomb threat was called in to the Munich Central Station: an anonymous caller directed police to a locker, where they found a communiqué from the RAF, the 2nd of June Movement, and the Revolutionary Cells denouncing the previous day’s attack.) In October, a bomb was discovered and defused in the Nuremberg train station, claimed by a phantom “Southern Fighting Group of the RAF.” Finally, in November 1975, a similar bomb went off in the Cologne train station.

As with the Hamburg attack, the RAF denounced all these as false flag actions, and released its own communiqués disavowing them, insisting that “the urban guerilla cannot resort to terrorism as a weapon.”10 Instead, it suggested that they were the work of either a CIA unit or else a neofascist group controlled by state security: this is not as farfetched a theory as it may seem, such scenarios having played themselves out elsewhere in Europe in the 1970s.11

Nor was the media neglected as a weapon to be wielded against the guerilla.

In May 1975, within a month of the Stockholm action and the start of the Stammheim pretrial hearings, the government announced that the RAF had “possibly” managed to steal mustard gas from an army depot.1 One German newspaper warned the public that:

Terrorists are planning a poison attack. The Federal Criminal Investigation Bureau informed the speaker of the German Bundestag on Thursday that members of the Baader-Meinhof gang are planning a poison attack on the German parliament. According to the Bureau’s reports, substantial quantities of poison gas which disappeared a few weeks ago from an army depot have fallen into the hands of members of the Baader-Meinhof gang … Health departments and hospitals have been prepared for the possibility of a terrorist attack with the chemical weapon.”2

It was later revealed, though less widely reported, that only two litres were missing, and that they might in fact have simply been misplaced. A few months later, it was admitted that this was in fact the case, and that they had since been found.

Nor was the phantom mustard gas scare an isolated case.3

An almost humorous example occurred in Munich when a judge taking the subway home from a party thought he recognized one of the RAF fugitives riding along with him: Rolf Pohle, who had been freed during the exchange for Lorenz earlier that year. Spiegel got wind of this and another ominous fact: a plan of the subway system had been reported missing from a telephone cabinet, clearly a newsworthy item in fastidious Bavaria. The magazine declared that all this pointed towards a possible impending RAF attack, and a full-scale manhunt was launched throughout the Land.

Nothing came of this, and government officials were later forced to admit that the judge in question had been “no longer quite sober” on the night in question.4

On top of such scaremongering news stories, an additional component of the state’s psychological warfare strategy was the trial of Ensslin, Baader, Raspe, and Meinhof—the Stammheim show trial.

The accused had never denied that they bore responsibility for the attacks in May 1972, establishing what would become the standard practice of all RAF members accepting responsibility for all RAF actions. Yet, this trial was no formality; rather, it was used as a forum for the state to “expose” the captured combatants as monsters and the RAF as something monstrous.

Although the defendants had been apprehended in 1972, the trial was not scheduled to begin until 1974; it was then postponed for an additional year to avoid any unpleasant publicity during the World Cup held in Stuttgart that summer.5 Next, its very location was turned into a propaganda statement about the danger posed by the accused: having the trial in the regular Stuttgart court house was deemed out of the question, and instead a special “terrorist-proof” facility was ordered built especially for the RAF’s alleged ringleaders.

As a journalist from the Sunday Times wrote in 1975:

That remarkable building is now almost complete in a sugar beet field near Stammheim prison. A concrete and steel fortress that will cost about £3 million, it includes among the features not normally found in courthouses, anti-aircraft defense against helicopter attack, listening devices sown in the ground around the building, scores of closed-circuit TV cameras, and an underground tunnel linked to Stammheim so that the defendants can be smuggled in and out of court without showing their noses in the open. The five judges (no jury), the accused and all witnesses will sit behind bullet-proof glass security screens.

Photographing the new court-house is strictly forbidden. The site workmen were, literally, sworn to secrecy. Plain-clothes police patrol it constantly, and local farmers, to their disgust, must carry passes to get to their fields.6

In this already Orwellian setting, the prisoners were confronted with the testimony of those few of their former comrades who had agreed to cooperate in return for leniency, new identities, or simply as a result of being psychologically broken by isolation.

Karl-Heinz Ruhland, who had proven an embarrassment to the state in the first RAF trials, was now reinforced by a slightly more convincing turncoat: Gerhard Müller, a former SPK member, who had been captured along with Meinhof in 1972. After two and a half years of hunger strikes and isolation, Müller could take no more and finally broke during the third hunger strike, in the winter of 1974/75. Tempted with offers of leniency and threatened with a murder charge going back to Hamburg police officer Norbert Schmid in 1971, he agreed to work for the prosecution.

The murder case was dropped, and the charges relating to the May Offensive—for which he could have received life—culminated in a tenyear sentence, of which he was only required to serve half.1 The deal was further sweetened with offers of a new identity and the possibility of selling his story for a considerable sum.2 He eventually received 500,000 DM and was relocated to the United States.3

In exchange, Müller painted a nightmare picture of the RAF as brutal killers, accusing Baader in particular of having executed one member, Ingeborg Barz, simply because she wished to opt out of the guerilla struggle.

Barz had joined the RAF in 1971 along with Wolfgang Grundmann; they had both been previously active in the anarchist prisoner support group Black Aid.4 While she is known to have participated in the Kaiserslautern bank robbery during which police officer Herbert Schoner was killed, she was never apprehended, nor did she ever surface from the underground. Disputing Müller’s claims, witnesses subsequently came forward testifying that they had met with Barz after this supposed execution, and when Müller brought police to the place where she was supposedly buried, they found nothing there.5

Brigitte Mohnhaupt took the witness stand to refute this story, describing in detail the various ways in which people might leave the guerilla, and insisting that, even in the case of traitors, the RAF had not carried out any executions. Given the growing list of former members who worked with the media and Buback’s prosecutors against the RAF and the glaring fact that none of them had been killed, Mohnhaupt’s statements were far more credible than Müller’s.

Another somewhat less important witness for the prosecution was Dierk Hoff, a metalworker and former SDS member from the Frankfurt scene. Hoff, who had built bombs and other weapons for the guerilla, testified that he had not realized what he was doing at the time. He claimed that Holger Meins, the conveniently dead former film student, had put him up to it with a story about how they were to be used as realistic props in a movie about terrorism. By the time he realized what was what, it was too late: the guerilla warned him that he was too deeply involved to be able to go to the police.

In exchange for his cooperation, Hoff’s somewhat incredible story was not challenged by the prosecution, and he received only a short prison term.6 Despite this, his testimony was not felt to be particularly damaging.

Supporters’ claims that all these broken witnesses were being paraded out not to secure a conviction (of which there was never any doubt) but to discredit the guerilla were vindicated at the eleventh hour as the trial was wrapping up. In January 1977, Otto Schily received a tip that Federal Judge Theodor Prinzing, who was in charge of the trial and was thus supposed to pretend to be impartial, had been passing on court documents and evidence to a judge from the appeals court. Copies of these documents had then been making their way to the press, accompanied by suggestions as to how they could be used to discredit the guerilla.

In his eagerness to exploit the testimony of Müller and the others, Prinzing had miscalculated, and in so doing provided the defense with one of its few legal victories: the Federal Judge was forced to recuse himself.7 He was replaced by associate judge Eberhard Foth, and the circus continued.

Nevertheless, the point had been made: this was a propaganda exercise, coordinated by either the BKA or the BAW, with a purely political goal. In other words, it was a show trial.

The prisoners defended themselves against all this as best they could: they may have accepted collective responsibility for all of the attacks the RAF had carried out, but they were far from indifferent about what was said in court. It was of great importance for them to counter allegations that could easily undermine what support they enjoyed on the left.

In her 1974 statement to the court regarding the liberation of Baader, Ulrike Meinhof had already attempted to refute the state’s slanders, and to place the guerilla’s actions within their proper political context. But the smears continued, and during the years of trials to come, the prisoners repeatedly felt compelled to defend not only their politics, but also their internal structure in the face of accusations of authoritarianism and cold inhumanity.

Quoted out of context, the prisoners’ attempts to defend their past practice can seem exaggerated, even shrill. The desire to paint one’s own experiences in the most favorable light can easily backfire, making one appear to be an uncritical enthusiast, dewy-eyed, if not fanatical, which is precisely what we are told to expect from self-styled revolutionaries. Nevertheless, it is difficult to see what else they could have done, as the state moved to use their various trials as so many opportunities to present its cockamamie stories and slanders.

In this context, the prisoners had little choice but to do what they could to affirm their political identity and continuing solidarity with one another.

These are excerpts from Brigitte Mohnhaupt’s testimony at Stammheim; a cruder but more complete translation is available at http://www.germanguerilla.com/red-army-faction/documents/76_0708_mohnhaupt_pohl.html. (M. & S.)

ON MÜLLER’S CLAIMS

REGARDING THE “LIQUIDATION” OF COMRADES

Of course there were people who left. It would be untrue to say otherwise. Contradictions develop within a group engaged in the process that this one is engaged in. In the course of the struggle, there are obviously contradictions, and there are people who decide at a certain point to no longer do the job, because they no longer want to.

They decide to return to their previous lives, to go back, or they do other things, even though everyone knows perfectly well that it isn’t possible, that it is a lie, when one has already been engaged in a practice such as ours. Such a decision can only be a step backwards, which always signifies a step backwards into shit.

There were departures like that, but there was obviously never a question of liquidation at any point or regarding any departure. There were departures involving people who, as I’ve already said, could no longer do the work, who no longer wanted to do it, because they understood that it meant going underground, which is what armed struggle always means. It was a completely free decision on their part. Leaving was the right thing for them to do. It would be stupid for them to stay, because there wouldn’t, in any case, be any way to engage in a shared practice.

There were also departures that we ourselves decided upon. There were people who knew that we were ending relations with them for clear reasons, basically for the same reason, because, at a given point, it was no longer possible to have a shared practice, because contradictions had developed. And, yeah, they’re all still alive, that’s all complete nonsense—it unfolded completely normally. They do other things, conscious that they can never again engage in this practice.

Maybe it should be explained how things would happen when someone decided to stop. It always happened in the course of a discussion in which everyone participated, or at least a good number of people, everyone who could participate, given the circumstances.

This took place in the context of discussions. It wasn’t done in a heavy-handed way. Each time there was an evolution which allowed the person concerned—along with all the others, each person in the group—to understand that the point had been reached where it was no longer possible to work together, the time had come for him to make a decision: to change, if he still wanted to, if he could manage it, if he could, obviously, with the help of all the others—or else he can leave.

At that point, he is free to leave, and there is no pressure, because it’s his decision, because he understands this, and because throughout it all there is no loss of self-respect, he is not rejected. It could not possibly have been handled any other way given the structure.

That is what makes this Hausner story of Müller’s absolutely impossible. Under certain specific circumstances, liquidation is obviously an option. But within the context of what the group was doing in 72, it would have been an error in that situation.

It is absolutely untrue that Hausner wanted to leave, and it is also completely untrue that we had said he should leave. There was absolutely no reason, given who he was, given what he had done, that would have led us to force him to leave or to have liquidated him. It’s absolutely ridiculous. It never happened. Obviously, everyone makes mistakes, but nobody had the arrogance or the absolutism to say, “Me, I don’t make mistakes.”

In any case, given the situation within the group, it is a swinish lie that we would have said, “Now he must leave, and if he doesn’t leave, then …”—what Müller said was, “If he couldn’t go to Holland, if he couldn’t be sent to a foreign country, then it was necessary, as an emergency solution, to simply liquidate him.”

If such a thing could have happened, it would have weakened and destroyed the structure, destroyed the group, destroyed the individuals who had struggled as part of the group, rather than strengthening them, because if something like that could happen in the group how would it remain possible for individuals to struggle, to be courageous, and above all to find their identities?

I maintain that it is impossible, even as an emergency solution or because there was no more place for someone, for things to have functioned in the way Müller described. It’s complete nonsense.

Is this clear yet?

I can give another example: the story of the woman in Berlin, Edelgard Graefer, I believe—in any case it was Graefer—who denounced a half a dozen people. She betrayed the people and gave away safehouses. And what happened? What was done? She got a slap in the mouth and was hit in the throat with a placard. So, I think these facts speak for themselves: when someone betrays people, in effect lines them up against the wall, because you never know what could happen when the cops break into an apartment, and this person only receives a slap in the head, then it is all the more absurd to think that someone who has never betrayed anyone could, as the result of a situation where everything culminates, as Müller describes it, in searches and whatever, in arrests, could simply be shot down. It’s absolutely out of the question.

And, of course, the strongest evidence, I would say, that this story can’t be true is simply that Siegfried Hausner led the Holger Meins Commando, and it would have been out of the question for it to be otherwise. Quite simply, he made the arrangements, he did it himself, which clarifies the nature of the structure that existed at the time. I believe this clarifies everything. Why would he have done it? Why would he have struggled in a situation like the one Müller described?

ON MÜLLER’S CLAIMS

REGARDING THE SPRINGER BOMBING

For instance, the statement which suggests that Ulrike carried out the attack against the Springer Building over the objections of Andreas or Gudrun or in opposition to a part of the group, and the claim that this led to a split, or, at least, to conflict between members, terror, or whatever it was that the pig said.

The truth is that when the Hamburg action was carried out—and this was already clarified during this trial—we knew nothing because of the structure of our groups: decisions were made autonomously, and actions were carried out autonomously. After the action against Springer, there was a lot of criticism from other groups. As a result, Ulrike went to Hamburg to find out what had happened, because the RAF never considered actions if there was a risk that civilians could be hurt. It was an essential principle in all discussions and in the criticism addressed to the Hamburg group, that they carried out the action without clearly considering that Springer, of course, wouldn’t evacuate the building. So given this, it had not been well prepared. That was the criticism made of the group that had carried out the action.

That is why Ulrike went to Hamburg at that time, to clarify this, to find out what had happened. After doing this, she formulated the statement about this action, in which everything was explained, the entire process, the warnings, Springer not evacuating, etc.

Which shows that what Müller said, yeah, we know that already, and we know why he’s saying it. What he claims now, regarding Ulrike, that she had or could have intended to carry out actions that the others objected to, it is completely absurd, but it fits in perfectly with the current line: “the tensions.” Its purpose is to legitimize Ulrike’s murder. The claim that there were tensions is a story that goes back—according to what Müller has said here—to Hamburg, to the organization of the group in 71-72. It is purely and simply a fabrication, presented here with the sole objective of legitimizing the murder …

Brigitte Mohnhaup

Stammheim Trial

July 22, 1976

The following text was read by Ulrike Meinhof at her trial alongside Hans-Jürgen Bäcker and Horst Mahler. (M. & S.)

This trial is a tactical maneuver, a part of the psychological war being waged against us by the BKA, the BAW, and the justice system:

• with the goal of obfuscating both the political ramifications of our trials and the BAW’s extermination strategy in West Germany;

• with the goal of using separate convictions to create the appearance of division, by putting only a few of us on display at any one time;

• with the goal of erasing the political context of all the RAF prisoners’ trials from the public consciousness;

• with the goal of forever eliminating from the people’s consciousness the fact that on the imperialist terrain of West Germany and West Berlin there is a revolutionary urban guerilla movement.1

We—the Red Army Faction—will not participate in this trial.

THE ANTI-IMPERIALIST STRUGGLE

If it is to be more than just an empty slogan, the struggle against imperialism must aim to annihilate, to destroy, to smash the system of imperialist domination—on the political, economic, and military planes. It must aim to smash the cultural institutions that imperialism uses to bind together the ruling elites and the communications structure that ensures their ideological control.

In the international context, the elimination of imperialism on the military plane means the elimination of U.S. imperialism’s military alliances throughout the world, and here that means the elimination of NATO and the Bundeswehr. In the national context it means the elimination of the state’s armed formations, which embody the ruling class’ monopoly of violence and its state power: the police, the BGS, the secret service. On the economic plane, it means the elimination of the power structure that represents the multinational corporations. On the political plane, it means the elimination of the bureaucracies, organizations, and power structures, whether state or non-state (parties, unions, the media), that dominate the people.

PROLETARIAN INTERNATIONALISM

The struggle against imperialism here is not and could not be a national liberation struggle. Socialism in one country is not its historical perspective. Faced with the transnational organization of capital and the military alliances with which U.S. imperialism encircles the world, the cooperation of the police and the secret services, the way the dominant elite is organized internationally within U.S. imperialism’s sphere of power—faced with all of this, our side, the side of the proletariat, responds with the struggle of the revolutionary classes, the people’s liberation movements in the Third World, and the urban guerilla in imperialism’s metropole. That is proletarian internationalism.

Ever since the Paris Commune, it has been clear that a people who seek to liberate themselves within the national framework in an imperialist state attract the vengeance, the armed might, and deadly hostility of the bourgeoisie of all the other imperialist states. That is why NATO is currently putting together an intervention force, to be stationed in Italy, with which to respond to internal difficulties.

Marx said, “A people who oppress another cannot themselves be free.” The military significance of the urban guerilla in the metropole—the RAF here, the Red Brigades in Italy, and the United Peoples Liberation Army1 in the U.S.A.—lies in the fact that it can attack imperialism here in its rear base, from which it sends its troops, its arms, its instructors, its technology, its communication systems, and its cultural fascism to oppress and exploit the people of the Third World. This is because it operates within the framework of the Third World liberation struggles, struggling in solidarity with them. That is the strategic starting point of the guerilla in the metropole: to unleash the guerilla, the armed struggle against imperialism, and the people’s war in imperialism’s rear bases, to begin a long-term process. Because world revolution is surely not an affair of a few days, a few weeks, or a few months, because it is not an affair of a few popular uprisings, it will not be a short process. It is not a question of taking control of the state as the revisionist parties and groups imagine—or, more correctly, as they claim, for they don’t really have any imagination.

THE NOTION OF THE NATION STATE

In the metropole, the notion of the nation state has become a hollow fiction, given the reality of the ruling classes, their policies, and their structure of domination, which no longer has anything to do with linguistic divisions, as there are millions of immigrant workers in the rich countries of Western Europe. The current reality—given the globalization of capital, given the new media, given the mutual dependencies that support economic development, given the growth of the European Community, and given the crisis—while remaining subjective, greatly encourages the formation of European proletarian internationalism, to the point that the unions have worked for years to box it in, to control it, to institutionalize it, and to repress it.

The fiction of the nation state, to which the revisionist groups are attached with their organizational form, is in keeping with their fetish for legality, their pacifism, and their massive opportunism. We are not reproaching the members of these groups for coming from the petit bourgeoisie, but for reproducing, in their politics and in their organizational structure, the ideology of the petit bourgeoisie, which has always been hostile to proletarian internationalism—their class position and conditions of social reproduction cannot be seen otherwise. They are always organized within the state as a complement to the national bourgeoisie, to the dominant class.

As for ourselves—we of the RAF, revolutionary prisoners detained in isolation, in special units, subjected to highly structured and completely illegal brainwashing programs in prison, as well as those underground— the argument that the masses are not yet sufficiently advanced just reminds us of what the colonialist pigs have been saying about Africa and Asia for the past seventy years. According to them, blacks, illiterates, slaves, colonized peoples, torture victims, the oppressed, and the starving, who suffer under the yoke of colonialism and imperialism, are not yet advanced enough to control their own administration like human beings. According to them, they are not yet advanced enough to control their own industrialization, their own education, their own future. This is the argument of people concerned with their own positions of power, those who want to rule the people, not to emancipate them or to help them in their struggle for liberation.

Our action on May 14, 1970, was and remains an exemplary action for the guerilla in the metropole. It contained all of the elements required for a strategy of armed struggle against imperialism. It served to free a prisoner from the grip of the state. It was a guerilla action, an action of a group that, in deciding to carry it out, organized itself as a politico-military cell. They acted to free a revolutionary, a cadre who was and remains indispensable for organizing the guerilla in the metropole. And not only indispensable like every revolutionary is indispensable in the ranks of the revolution, for already at this stage, he embodied everything that made the guerilla possible, that made possible the politico-military offensive against the imperialist state. He embodied the determination, the will to act, the ability to orient himself solely and exclusively in terms of the objectives, while leaving space for the collective learning process, and practicing leadership collectively right from the start, mediating between each person’s individual experience and the collective as a whole.

This action was exemplary, because in the struggle against imperialism it is necessary above all to liberate the prisoners, to liberate them from prison, which has always been an institution used against all of the exploited and oppressed, historically leading only to death, terror, fascism, and barbarism. To liberate them from their imprisonment within the most complete and utter alienation, from their self-alienation, from the state of political and existential disaster in which the people are obliged to live while in the grip of imperialism, of consumer society, of the media, and of the ruling class structures of social control, where they remain dependent on the market and the state.

The guerilla—and not only here: it is the same in Brazil, in Uruguay, in Cuba, and, for Che, in Bolivia—always starts from point zero, and the first phase of its development is the most difficult. Neither the bourgeois class prostituted to imperialism, nor the proletariat colonized by it, provide anything of use to us in this struggle. We are a group of comrades who have decided to act—to break with the stage of lethargy, of purely rhetorical radicalism, of increasingly vain discussions about strategy—and to struggle. We are lacking in everything, not only the capacity to act: it is only now that we are discovering what sort of human beings we are. We are uncovering the metropolitan individualism that comes from the system’s decay, the alienated, false, poisonous relationships that it creates in our lives—in the factories, the offices, the schools, the universities, the revisionist groups, during apprenticeships, or at part time jobs. We are discovering the effects of the division between professional life and private life, the division between intellectual labor and manual labor, the childishness of the hierarchical labor process, all of which reflect the psychic distortions produced by consumer society, by this degenerate metropolitan society, fallen into decay and stagnation.

But that is who we are, that is where we come from. We are the offspring of metropolitan annihilation and destruction, of the war of all against all, of the conflict of each individual with every other individual, of a system governed by fear, of the compulsion to produce, of the profit of one to the detriment of others, of the division of people into men and women, young and old, sick and healthy, foreigners and Germans, and of the struggle for prestige. Where do we come from? From isolation in individual row-houses, from the suburban concrete cities, from prison cells, from the asylums and special units, from media brainwashing, from consumerism, from corporal punishment, from the ideology of nonviolence, from depression, from illness, from degradation, from humiliation, from the debasement of human beings, from all the people exploited by imperialism.

We must find, in our distress, the need to liberate ourselves from imperialism and to struggle against it. We must understand that we have nothing to lose by destroying the system, but everything to gain from armed struggle—collective liberation, life, human dignity, and our identity. We must understand that the cause of the people, the masses, the assembly line workers, the lumpen proletariat, the prisoners, the apprentices—the lowest of the masses here and the liberation movements in the Third World—is our cause. Our cause—armed struggle against imperialism—is the masses’ cause and vice versa, even if it can only become a reality through a long-term process whereby the politico-military offensive develops and people’s war breaks out.

That is the difference between true revolutionary politics and politics that only seem revolutionary, but are in fact opportunist. It is necessary that we start from the objective situation, from the objective conditions, from the actual situation of the proletariat and the masses in the metropole, from the fact that all layers of society are in all ways under the system’s control. The opportunists base themselves on the alienated consciousness of the proletariat; we start from the fact of their alienation, which indicates why their liberation is necessary.

In 1916 Lenin responded to the colonialist, renegade pig Kautsky:

No one can seriously think it possible to organise the majority of the proletariat under capitalism. Secondly—and this is the main point—it is not so much a question of the size of an organisation, as of the real, objective significance of its policy: does its policy represent the masses, does it serve them, i.e., does it aim at their liberation from capitalism, or does it represent the interests of the minority, the minority’s reconciliation with capitalism?

Neither we nor anyone else can calculate precisely what portion of the proletariat is following and will follow the social-chauvinists and opportunists. This will be revealed only by the struggle, it will be definitely decided only by the socialist revolution. And it is therefore our duty, if we wish to remain socialists to go down lower and deeper, to the real masses; this is the whole meaning and the whole purport of the struggle against opportunism.1

THE GUERILLA IS THE GROUP

The role of the guerilla leadership, the role of Andreas in the RAF, is to provide orientation. It is not only a matter of distinguishing what is essential from what is secondary in each situation, but also of knowing how to connect each situation to the greater political context by elaborating its particularities, while never losing sight of the goal—revolution—as a result of details or specific technical or logistical problems, never losing sight of the overall tactical or strategic politics of the alliance, the question of class. This means never falling into opportunism.

This, said Le Duan,2 is “the art of dialectically connecting firm principles with flexibility in action, the art of applying the law of development that seeks to see incremental changes transformed into qualitative leaps within the revolution.”3 It is also the art of “never shrinking from the unimaginable enormity of your goals,” but of pursuing them stubbornly and without allowing yourself to be discouraged. It is the courage to draw lessons from your errors and the general willingness to learn. Every revolutionary organization and every guerilla organization knows that practice requires that it develop its capabilities—at least any organization applying dialectical materialism, any organization that aims for victory in the people’s war and not the edification of a party bureaucracy and a partnership with the imperialist power.

We don’t talk about democratic centralism because the urban guerilla in the metropole of the Federal Republic can’t have a centralizing apparatus. It is not a party, but a politico-military organization within which leadership is exercised collectively by all of the independent sections, with a tendency for it to be subsumed by the group as part of the collective learning process. Tactically, the goal is to always allow for an autonomous orientation towards militants, guerillas, and cadres. Collectivity is a political process that functions on all levels: in interaction and communication and in the sharing of knowledge that occurs as we work and learn together. An authoritarian leadership structure would find no material basis in the guerilla, because the real (i.e., voluntary) development of each individual’s productive force is necessary for the revolutionary guerilla to make an effective revolutionary intervention from a position of weakness, in order to launch the people’s liberation war.

PSYCHOLOGICAL WARFARE

Andreas, because he is a revolutionary, and was one from the beginning, is the primary target of the psychological war that the cops are waging against us. This has been the case since 1970, since the first appearance of the urban guerilla with the prison break operation.

The guiding principle of psychological warfare is to set the people against the guerilla, to isolate the guerilla from the people, to distort the real, material goals of the revolution by personalizing events and by presenting them in psychological terms. The goals of the revolution are freedom from imperialist domination, from occupation, from colonialism and neocolonialism, from the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, from military dictatorship, from exploitation, from fascism, and from imperialism. Psychological warfare uses the tactic of mystifying that which is easy enough to understand, presenting as irrational that which is rational, and presenting the revolutionaries’ humanity as inhumanity. This is carried out by means of defamation, lies, insults, bullshit, racism, manipulation, and the mobilization of the people’s unconscious fears and reflexes inculcated over decades or centuries of colonial domination and exploitation—knee-jerk existential fear in the face of incomprehensible and hidden powers of domination.

Through psychological warfare, the cops attempt to eliminate revolutionary politics and the armed anti-imperialist struggle in the German metropole, as well as its effect on the consciousness of the people, by personalizing it and turning it into a psychological issue. In this way, the cops attempt to present us as what they themselves are, they attempt to present the RAF’s structure as similar to their own, a structure of domination mimicking the organizational form and functioning of their own structures of domination, a structure like that of the Ku Klux Klan, the mafia, or the CIA. And they accuse us of the tactics that imperialism and its puppets use to impose themselves: extortion, corruption, competition, privilege, brutality, and the practice of stepping over corpses to achieve their goals.

In their use of psychological warfare against us, the cops rely upon the confusion of all those who are obliged to sell their labor simply to survive, a confusion born of the obligation to produce and of the fear for one’s very existence that the system generates within them. They rely on the morbid practice of defamation, which the ruling class has directed against the people for decades, for centuries; a mixture of anticommunism, antisemitism, racism, sexual oppression, religious oppression, and an authoritarian educational system. They rely on consumer society brainwashing and the imperialist media, re-education and the “economic miracle.”

What is shocking about our guerilla in its first phase, what was shocking about its first actions, is that they showed that people could act outside of the system’s limits, that they didn’t have to see through the media’s eyes, that they could be free from fear—that people could act on the basis of their own very real experiences, their own and those of the people. Because the guerilla starts from the fact that—despite this country’s highly advanced technology and immense wealth— every day people have their own experiences with oppression, media terrorism, and insecure living conditions, which lead to mental illness, suicide, child abuse, indoctrination, and housing shortages. That is what the imperialist state finds shocking about our actions: that the people can understand the RAF for what it is: a practice, a cause born in a logical and dialectical way from actual relationships. A practice which—insofar as it is the expression of real relationships, insofar as it expresses the only real possibility for reversing and changing these relationships—gives the people their dignity and makes sense out of struggle, revolution, uprisings, defeats, and past revolts—that is to say, it returns to the people the possibility of being conscious of their own history. Because all history is the history of class struggle, a people who has lost a sense of the significance of revolutionary class struggle is forced to live in a state in which they no longer participate in history, in which they are deprived of their sense of self, that is to say, of their dignity.

The guerilla allows each person to determine where he stands, to define, often for the first time, his overall situation and to discover his place within class society, within imperialism: to determine this for himself. Many people think they are on the side of the people, but the moment the people start to confront the police and start to struggle, they cut and run, issue denunciations, put the brakes on, and side with the police. This is a problem that Marx often addressed: that one is not what one believes oneself to be, but what one is in one’s true functions, in one’s role within class society. That is to say, if one doesn’t decide to act against the system, doesn’t take up arms and fight, then one is on the system’s side and effectively serves as an instrument for achieving the system’s goals.

With psychological warfare, the cops attempt to turn the achievements of the guerilla’s actions back against us: the knowledge that it isn’t the people who are dependent on the state, but the state that is dependent on the people—that it isn’t the people who need the investment firms or the multinationals and their factories, but it is the capitalist pigs who need the people—that the goal of the police isn’t to protect the people from criminals, but to protect the imperialist order of exploitation from the people—that the people don’t need the justice system, but the justice system needs the people—that we don’t need the American troops and installations here, but that U.S. imperialism needs us. Through personalization and psychological rationalization, they project the clichés of capitalist anthropology onto us. They project the reality of their own facade, of their judges, of their prosecutors, of their screws, and of their fascists, pigs who take pleasure in their alienation, who only live by torturing, by oppressing, and by exploiting others, pigs for whom the whole point of their existence is their career, success, elbowing their way to the top, and taking advantage of others, pigs who take pleasure from the hunger, the misery, and the deprivation of millions of human beings in the Third World and here.

What the ruling class hates about us is that despite a hundred years of repression, of fascism, of anticommunism, of imperialist wars, and of genocides, the revolution once again raises its head. In carrying out psychological warfare, the bourgeoisie, with its police state, sees in us everything that they hate and fear about the people, and this is especially so in the case of Andreas. It is he who is the mob, the street, the enemy. They see in us that which menaces them and will overthrow them: the determination to provoke the revolution, revolutionary violence, and political and military action. At the same time they see their own powerlessness, for their power ends at the point when the people take up arms and begin to struggle.

The system is exposing itself, not us, in its defamation campaign. All defamation campaigns against the guerilla reveal something about those who carry them out, about their piggishness, about their goals, their ambitions, and their fears.

And to say we are “a vanguard that designates itself as such” makes no sense. To be the vanguard is a role that we cannot assign ourselves, nor is it one that we can demand. It is a role that the people give to the guerilla in their own consciousness, in the process of developing their consciousness, of rediscovering their role in history as they recognize themselves in the guerilla’s actions, because they, “in themselves,” recognize the necessity to destroy the system “for themselves” through guerilla actions. The idea of a “vanguard that designates itself as such” reflects ideas of prestige that belong to a ruling class that seeks to dominate. But that has nothing to do with the role of the proletariat, a role that is based on the absence of property, on emancipation, on dialectical materialism, and on the struggle against imperialism.

THE DIALECTIC

OF REVOLUTION AND COUNTERREVOLUTION

That is the dialectic of the anti-imperialist struggle. The enemy unmasks itself by its defensive maneuvers, by the system’s reaction, by the counterrevolutionary escalation, by the transformation of the political state of emergency into a military state of emergency. This is how it shows its true face—and by its terrorism it provokes the masses to rise up against it, reinforcing the contradictions and making revolution inevitable.

The basic principle of revolutionary strategy in conditions of permanent political crisis is to develop, in the city as well as in the countryside, such a breadth of revolutionary activity that the enemy finds himself obliged to transform the political situation in the country into a military situation. In this way dissatisfaction spreads to all layers of the population, with the military alone responsible for all of the hatred.

And as a Persian comrade, A.P. Puyan,1 said:

By extending the violence against the resistance fighters, creating an unanticipated reaction, the repression inevitably hits all other oppressed milieus and classes in an even more massive way. As a result, the ruling class augments the contradictions between the oppressed classes and itself and creates a climate which leads of necessity to a great leap forward in the consciousness of the masses.

And Marx said:

Revolutionary progress is proceeding in the right direction when it provokes a powerful, unified counterrevolution, which backfires by developing an adversary that cannot lead the party of the insurrection against the counterrevolution except by becoming a truly revolutionary party.2

In 1972, the cops mobilized 150,000 men to hunt the RAF, using television to involve the people in the manhunt, having the Federal Chancellor intervene, and centralizing all police forces in the hands of the BKA. This makes it clear that, already at that point, a numerically insignificant group of revolutionaries was all it took to set in motion all of the material and human resources of the state. It was already clear that the state’s monopoly of violence had material limits, that their forces could be exhausted, that if, on the tactical level, imperialism is a beast that devours humans, on the strategic level it is a paper tiger. It was clear that it is up to us whether the oppression continues, and it is also up to us to smash it.

Now, after everything they have carried out against us with their psychological warfare campaign, the pigs are preparing to assassinate Andreas. As of today, we political prisoners, members of the RAF and other anti-imperialist groups, are beginning a hunger strike.1 We must add the fact that for some years now—in keeping with the police objective of liquidating the RAF, and consistent with their tactic of psychological warfare—most of us have found ourselves detained in isolation. Which is to say, we have found ourselves in the process of being exterminated. But we have decided not to stop thinking and struggling: we have decided to dump the rocks the state has thrown at us at its own feet.

The police are preparing to assassinate Andreas, as they attempted previously during the summer 1973 hunger strike when they deprived him of water. At that time, they attempted to have the lawyers and the public believe that he was allowed to drink again after a few days: in reality he received nothing, and the pig of a doctor at the Schwalmstadt prison, after nine days, when he had already gone blind, said, “If you don’t drink some milk, you’ll be dead in ten hours.” The Hessen Minister of Justice came from time to time to have a look in his cell, and the Hessen prison doctors’ group was at that time meeting with the Wiesbaden Minister of Justice. There exists a decree in Hessen that anticipates breaking hunger strikes by withholding all liquids. The complaints filed against the pig of a doctor for attempted murder were rejected, and the procedure undertaken to maintain the complaint was suspended.

We declare today that if the cops attempt to follow through with their plans to deprive Andreas of water, all RAF prisoners participating in the hunger strike will immediately react in turn by refusing all liquids. We will react in the same way if faced with any attempted assassination through the withholding of water, no matter where it occurs or against which prisoner it is used.

Ulrike Meinhof

September 13, 1974

RAF actions are never directed against the people. Given the choice of target, the bomb that exploded in the Bremen Central Station on Saturday bears the mark of the ongoing security police operation. To intimidate and control the people, they are no longer restricting themselves to the fascist tactic of threats:

• of bombings, as in Stuttgart in June 1972;

• of rocket attacks against the millions of spectators at the Soccer World Cup in March 1974;

• of poisoning the people’s drinking water in Baden-Württemberg in August 1974.2

The state security police have now escalated to provocative actions, with the risk of unleashing a bloodbath upon the people.

The RAF prisoners

December 9, 1974

All there is to say regarding our identity is that which remains of the moral person in this trial: nothing. In this trial, the moral person— this concept created by the authorities—has been liquidated in every possible way—both through the guilty sentence Schmidt has already pronounced and through the Federal Supreme Court decision relative to §231a1 of the Penal Code in the recent hearing before the Federal Administrative Court, which, by ratifying the Federal Supreme Court decision, has done away with the legal fictions of the Basic Law.

Given that the prisoners do not have any recognized rights, our identity is objectively reduced to the trial itself. And the trial is—this much one should perhaps say about the indictment—about an offense committed by an organization. The charges of murder and attempted murder are based on the concept of collective responsibility, a concept which has no basis in law. The entire indictment is demagogy—and this has become clear, just as it has become clear (ever since his outburst during the evidentiary hearing) why Prinzing must exclude us. As a result, it must be demagogically propped up with perjury and restrictions on our depositions. And we see how Prinzing sees things in a way that allows for a verdict even though there is no evidence; and so it becomes clear why he previously, and now for a second time, felt obliged to decimate the defense with a volley of legislation and illegal attacks.

We have been amused by this for some time now.

We consider what is going on here to be a masterpiece of reactionary art. Here, in this “palace of freedom” (as Prinzing calls these state security urinals), state security is pitifully subsumed within a mass of alienated activities. Or in other words, it’s as if the same piece is being played out on three superimposed levels of the same Renaissance stage—the military level, the judicial level, and the political level.

The indictment is based on a pack of lies.

After state security suppressed nine-tenths of the files—and, as Wunder stated, it wasn’t the BAW, but the BKA: the BAW itself, according to Wunder, is only familiar with a fraction of these files—they have been obliged to work with lies.

One of the lies is the claim that one can, using §129, construct an indictment that can allow for a “normal criminal trial”—even though this paragraph, since it inception, that is to say since the communist trials in Cologne in 1849,2 has been openly used to criminalize political activity, assimilating proletarian politics into criminality. So as to not disrupt normal criminal proceedings, they use the concept of “criminal association,” a concept that historically has only come into play when dealing with proletarian organizations.

It is a lie to say that the goal of a revolutionary organization is to commit reprehensible acts.

The revolutionary organization is not a legal entity, and its aims—we say, its goals and objectives—cannot be understood in dead categories like those found in the penal code, which represents the bourgeoisie’s ahistorical view of itself. As if, outside of the state apparatus and the imperialist financial oligarchy, there is anyone who commits crimes that have as their objective oppression, enslavement, murder, and fraud— which are only the watered down expressions of imperialism’s goals.

Given the role and the function that §129 has had in class conflicts since 1848, it is a special law. Ever since the trial of the Cologne Communists, since the Bismarck Socialist Laws, since the “law against participation in associations that are enemies of the state” during the Weimar Republic, its legacy and essence has been to criminalize the extra-parliamentary opposition by institutionalizing anticommunism within parliament’s legal machinery.

In and of itself, bourgeois democracy—which in Germany has taken form as a constitutional state—has always found its fascist complement to the degree that it legalizes the liquidation of the extra-parliamentary opposition, with its tendency to become antagonistic. In this sense, justice has always been class justice, which is to say, political justice.

In other words, bourgeois democracy is inherently dysfunctional given its role in stifling class struggle when different factions of capital come in conflict with each other within the competitive capitalist system. In the bourgeois constitution, it anticipates the class struggle as class war. Communists have always been outlaws in Germany, and anticommunism a given.

That also means that Prinzing—with his absurd claim that this is a “normal criminal trial” despite the fact that the charges are based on this special law—is operating in an absolute historical vacuum, which explains his hysteria. The BAW operates in a legal vacuum situated somewhere between the bourgeois constitutional state and open fascism. Nothing is normal and everything is the “exception,” with the objective of rendering such a situation the norm. Even the state’s reaction—which of course this judge fails to grasp—places our treatment in the historical tradition of the persecution of extra-parliamentary opposition to the bourgeois state. Prinzing himself, with §129, establishes the historical identity this state shares with the Kaiser’s Reich, the Weimar Republic, and the Third Reich. The latter was simply more thorough in its criminalization and destruction of the extra-parliamentary opposition than the Weimar Republic and the Federal Republic.

Finally, this paragraph conveys the conscious nature of this political corruption of justice, as it violates the constitutional idea that “Nobody can be deprived of …,” and because today, just as in the 50s, it lays the basis for trials based on opinions, that is to say, for the criminalization of opinions.

It is a paragraph that is dysfunctional, given that the bourgeois state claims that the bourgeoisie is by its very nature the political class. Within the bourgeois state’s system of self-justification, it reflects the fact that the system—capitalism—is transitory, as their special law against class antagonism undermines the ideology of the bourgeois state.

As a special law, it cannot produce any consensus, and no consensus is expected. It equates the monopoly of violence with parliamentarianism and private ownership of the means of production. Clearly, this law is also an expression of the weakness of the proletariat here since 45. They want to legally safeguard the situation that the U.S. occupation forces established here, by destroying all examples of autonomous and antagonistic organization.

The entire construct, with its lies, simply reveals the degree to which the imperialist superstructure has lost touch with its own base, has lost touch with everything that makes up life and history. It reveals the deep contradiction found at the heart of the break between society and the state. It reveals the degree to which all the factors that mediate between real life and imperialist legality are dispensed with in this, the most advanced stage of imperialism. They are antagonistic. The relationship is one of war, within which maintaining legitimacy is reduced to simply camouflaging nakedly opportunist calculations.

In short, we only intend to refer to the concept of an offense committed by an organization, which forms the entire basis for Buback’s charge, and which—as it is the only way possible—has been developed through propaganda.

But we also do this in the sense of Blanqui: the revolutionary organization will naturally be considered criminal until the old order of bourgeois ownership of the means of production that criminalizes us is replaced by a new order—an order that establishes the social appropriation of social production.

The law, as long as there are classes, as long as human beings dominate other human beings, is a question of power.

The RAF Prisoners

August 19, 1975

THE BOMB ATTACK IN MUNICH CENTRAL STATION

In order to create greater publicity for this statement from the guerilla regarding the right-wing attacks, on September 14, 1975, we announced that a bomb would explode in Munich Central Station at 6:50 PM. At 6:55 PM, we telephoned to direct the search to locker 2005, in which, rather than a bomb, the following statement was found:

Disappointed that once again there is no “bloodbath” to blame on “violent anarchists,” as was the case in Birmingham,1 in Milan,2 and most recently here at home, in Bremen in December 74, and yesterday in Hamburg?

This is to make something perfectly clear to you cops and those of you on the editorial staffs of the newspapers and the radio stations:

The guerilla’s statements and practice show that their attacks are directed against the ruling class and their resistance is against the system’s oppression.

• In June 72, the police tried to create panic in Stuttgart with bomb threats. They used the World Cup to threaten thousands with claims that the guerilla planned rocket attacks against football stadiums. As part of their intimidation, they spoke of a plan to poison the drinking water in Baden-Würrtemberg. In Bremen, in December 74, and yesterday in Hamburg, provocateurs acted for real: explosives were set off in the midst of large groups of people. Without any consideration for the health and wellbeing of the people, they turned their threats into deeds, doing everything they can to increase the agitation against the radical left and the guerilla.

• The guerilla in Germany has attacked the U.S. Army, which was engaged in a war against the Vietnamese people. The guerilla has bombed the Federal Constitutional Court, the capitalist associations, and the enemies of the Chilean and Palestinian people. They kidnapped the CDU leader Lorenz to gain the freedom of political prisoners. They struggle against rising prices and the increased pressure brought to bear on the people, e.g., the Berlin transit price actions.3

We demand that the press, the radios, and TV broadcast this statement!

We are the urban guerilla groups

Red Army Faction

2nd of June Movement

Revolutionary Cells

And above all struggle against those who are responsible for planning and carrying out the attacks in Bremen and Hamburg. The choice of targets shows who the culprits are. […]4

Red Army Faction

2nd of June Movement

Revolutionary Cells

September 14, 1975

In the face of the state propaganda effort to tie the attack at the Hamburg Central Station to the RAF, we state clearly: the nature of this explosion speaks the language of reaction. It can only be understood as part of the psychological war that state security is waging against the urban guerilla. The method and objective of this crime against the people bear the mark of a fascist provocation.

The political-military actions of the urban guerilla are never directed against the people. The RAF’s attacks target the imperialist apparatus, its military, political, economic, and cultural institutions and its functionaries in the repressive and ideological state structures.

In its offensive against the state, the urban guerilla cannot resort to terrorism as a weapon. The urban guerilla operates in the rift between the state and the masses, working to widen it and to develop political consciousness, revolutionary solidarity, and proletarian power against the state.

In opposition to this, this intelligence service-directed terrorist provocation against the people is meant to increase fear and strengthen the people’s identification with the state. At the Hessen Forum, Wassermann, the President of the Braunschweig Court of Appeals explained the state security countertactic—in his words, one must “increase citizens’ feelings of insecurity” and “act on the basis of this subjective feeling of fear.”

In the meantime, the Frankfurter Rundschau report (September 9) confirmed that the state security counter-operations conducted since 72 (bomb threats against Stuttgart, threats to poison drinking water, stolen stocks of mustard gas, SAM rocket attacks on football stadiums, the bomb attack on Bremen Central Station and now in Hamburg) were developed from programs created by the CIA. The FR is only substantiating what has been known for a long time now, that the use of poison in subway tunnels and the contamination of drinking water in large cities is a special warfare countertactic, a “psychological operation” of intelligence services and counterguerilla units.

At this point, the question to be answered is whether the attack in Hamburg was the act of a lone criminal, of the radical right-wing Bremen group under intelligence service control, of state security itself, or of the special CIA counterinsurgency unit established at the American embassy in Bonn after Stockholm.

What is certain is that state security works within the reactionary structures through a network of state security journalists who use the media conglomerates and public institutions to attack the urban guerilla. High profile figures in this network close to the BKA’s press office and the BAW press conferences are Krumm of the Frankfurter Rundschau, Busche of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Leicht and Kuchnert of the Süddeutsche Zeitung, and Rieber and Zimmermann, who are published in many national newspapers. Zimmermann’s article about the alleged connection between the attack, the RAF, the 2nd of June Movement, and Siegfried Haag was simultaneously published in eight national newspapers.

The incredible fact that state reaction is now resorting to such measures against the weak urban guerilla here simply indicates the strategic importance of this instability for the Federal Republic as part of the U.S. imperialist chain of states. In the North-South and East-West conflicts, the FRG is a central base of operations for U.S. imperialism; militarily in NATO, economically in the European Community, politically and ideologically through the Social Democrats and their leadership role in the Socialist International.

The state’s attempt to use its intelligence services to provoke a reactionary mass mobilization is not a response to the guerilla, but is rather a reaction to strategic conditions; namely, the economic and political weakness of the U.S. chain of states. They are responding to the future potential and current reality of revolutionary politics. The objective and function of psychological warfare, in the way it is being waged against every democratic initiative, is to cause splits, isolation, withdrawal and eventually extermination.

Marx said, “Revolutionary progress disrupts the course of a closed and powerful counterrevolution by producing rebels who convert the party of resistance into a truly revolutionary party.”1

The urban guerilla has shown that the only way to resist state terror is through armed proletarian politics.

The RAF Prisoners

Stammheim

September 23, 1975

On the night of November 11-12, state security agents and/or fascists again set off a bomb in a train station—first Hamburg and Nuremberg, and now Cologne.

The federal government’s Terrorism Division and the cops hoped to create a bloodbath with this pointless act of terrorism. In Bremen and Hamburg, the bombs exploded on Federal Football League game days. In Cologne, the Carnival began on November 11, certainly a night when many people would be out; it was only by chance that no one was injured. […]

The urban guerilla has often stated, and has proven through its practice since 1970, that its actions are never and have never been directed against the people. […]1

Red Army Faction

2nd of June Movement

Revolutionary Cells

November 1975