Reading 14

Genocide Denied

The readings in this chapter describe the difficult struggles toward justice and reconciliation in the aftermath of war and mass violence. But what happens when those struggles never even begin? What happens to a history that has not been judged or even acknowledged?

In April 2015, people around the world marked the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the Armenian Genocide (see “Genocide under the Cover of War” in Chapter 3). Yet in Turkey and the former lands of the Ottoman Empire, where the murder of more than a million Armenians took place, these events have never been officially accepted as true by the government. At the end of World War I, the three leaders most responsible for planning the destruction of the Armenians escaped from Turkey; though they were tried in absentia, they never faced punishment. One of those leaders, Mehmed Talaat, claimed in his memoirs that there were no deliberate plans to massacre Armenians. When those memoirs were published after Talaat’s death, they set the pattern for the arguments still used to distort the history: the false claim that the Armenians were traitors who deserved to be deported and who died as a result of a civil war in which both sides committed atrocities.

Within Turkey, individual citizens and scholars have acknowledged the genocide, holding academic conferences and organizing commemorative events. But despite overwhelming historical evidence, including primary sources, eyewitness accounts, testimony of perpetrators, survivor recollections, and physical evidence, the government of Turkey denies that a genocide took place. Those who deny what happened have used many strategies in their attempt to turn a historical fact into a matter for debate or even a myth. They have funded their own academic centers dedicated to spreading a revised history, and they have intimidated scholars who study and write about the genocide. Some authors who wrote about the genocide have been brought to trial for insulting “Turkishness,” which is a crime in Turkey. Turkish officials worked to censor United Nations reports by blocking mentions of the genocide and by countering resolutions in the United States that would have recognized April 24 as a national day of remembrance of the Armenian Genocide. While some countries, including France and Germany, have officially recognized the Armenian Genocide, many others have not. Leaders of many countries, including the United States, have been reluctant to force Turkey to acknowledge the genocide because they don’t want to embarrass or alienate an important ally.

Denial has consequences. It prevents attempts to seek appropriate restitution for the victims, and it can undermine the feeling of belonging and security for Armenians still living in Turkey. In 1998, more than 100 prominent scholars signed a petition that opposed denial of the Armenian Genocide. It said, in part:

Denial of genocide strives to reshape history in order to demonize victims and rehabilitate the perpetrators. Denial of genocide is the final stage of genocide. It is what Elie Wiesel has called a “double killing.” Denial murders the dignity of survivors and seeks to destroy remembrance of the crime. In a century plagued by genocide, we affirm the moral necessity of remembering.78

In 2015, on the 100th anniversary of the genocide, journalist Raffi Khatchadourian described how denial of the genocide affects the Armenian community worldwide. He wrote:

Armenians continue to struggle with the official negation: to endlessly combat it is its own form of prison, but to try moving past it unilaterally, abandoning the horrific events of 1915 in the shadows of denial, is to succumb to willful blindness and injustice.79

Denial, he says, is not just an absence of truth but a “wounding instrument. And, after a hundred years of it, it is hard to feel Armenian in a meaningful way without defining oneself in opposition to it.”80

Historian Taner Akçam has said that acknowledging the genocide matters deeply outside the Armenian world, too. He responded with three key reasons when asked, Why is recognizing the Armenian Genocide important?

One, to respect the victims, to accept their dignity and to give an end to their traumas. Second, it is very important for the reconciliation in a society, for the democracy and for the human rights. If a society cannot face its own history, it cannot establish a democratic future. And the third factor is, related to the second one, if you want to say the sentence “never again,” it can only be possible if society faces its past, its history. If a society, if a state, doesn’t acknowledge its wrongdoing in the past, this means there is a potential there, always, that it can do it again.81

Connection Questions

1. What are some of the consequences of the denial of the Armenian Genocide? How does it influence people who have ties to Armenia? Does it matter for people who do not?

2. What are some reasons why the official Turkish denial of the genocide has persisted for more than a century?

3. Why did the authors of the petition believe that there is a “moral necessity of remembering”? Do you agree?

4. How is a nation’s identity connected to its history? Why does Taner Akçam say that acknowledging the past is important for democracy and human rights? Do you agree?

Visual Essay

Holocaust Memorials and Monuments

Across Europe, and even around the globe, people have built memorials to commemorate the Holocaust. Each tries to preserve the collective memory of the generation that built the memorial and to shape the memories of generations to come. This visual essay explores several examples of memorials and monuments to the Holocaust and other histories of mass violence. We use the terms monuments and memorials more or less interchangeably. Some people distinguish between the two, saying that memorials are a response to loss and death and that monuments are more commemorative and celebratory in nature. However, when considering traditional memorials and monuments, there are so many exceptions to these definitions that here we will use the terms more loosely.

Memorials raise complex questions about which history we choose to remember. If a memorial cannot tell the whole story, then what part of the story, or whose story, does it tell? Whose memories, whose point of view, and whose values and perspectives will be represented? Memorials must also respond to the question, “Why should we remember?” Writing of memorials in Germany, Ian Buruma distinguishes between a Denkmal, a monument built to glorify a leader, an event, or the nation as a whole, and a Mahnmal, a “monument of warning.” Holocaust memorials, he says, are “monuments of warning.”82

Memorial makers must also decide how to express complex ideas in the visual vocabulary available to them. Shape, mass, material, imagery, location, and perhaps some words, names, or dates can communicate a memorial’s message. Legal scholar Martha Minow asks,

Should such memorials be literal or abstract? Should they honor the dead or disturb the very possibility of honor in atrocity? Should they be monumental, or instead disavow the monumental image, itself so associated with Nazism? Preserve memories or challenge as pretense the notion that memories ever exist outside the process of constructing them?83

Some observers wonder if memorials might have unintended consequences, undermining the memories that they are meant to preserve. Critic James Young has said of memorials, “It’s a big rock telling people what to think; it’s a big form that pretends to have a meaning, that sustains itself for eternity, that never changes over time, never evolves—it fixes history, it embalms or somehow stultifies it.”84 Young has suggested that memorials might actually let viewers become more passive and forgetful, because they “do our memory work for us.”85 Can monuments suggest closure when none exists and consequently insulate us from history or anesthetize us rather than engaging and challenging us?

With these concerns in mind, some artists have created “counter-memorials” that are designed to change over time, to create an awareness of something that is missing, or even to disappear, provoking viewers to question, think, and connect more actively. In Kassel, Germany, artist Horst Hoheisel created a counter-memorial on the site of a majestic, pyramid-shaped fountain that had been given to the city by a Jewish entrepreneur; the original fountain was demolished by the Nazis in 1939. Rather than restore it, Hoheisel created an underground fountain that is the mirror image of the one the Nazis destroyed. Hoheisel explained:

I have designed the new fountain as a mirror image of the old one, sunk beneath the old place in order to rescue the history of this place as a wound and as an open question, to penetrate the consciousness of the Kassel citizens so that such things never happen again . . . The sunken fountain is not the memorial at all. It is only history turned into a pedestal, an invitation to passersby who stand upon it to search for the memorial in their own heads. For only there is the memorial to be found.86

Connection Questions

1. As you explore the images in the visual essay, consider what message each memorial conveys. Who created and authorized the memorial? Who is the audience for this message? How is the message conveyed? Whose story is the memorial telling? What might the memorial be leaving out?

2. What are some key differences among the memorials pictured on the pages that follow? What do they have in common? Which one speaks to you most strongly?

3. Memorials have many different kinds of goals, including telling an accurate story of the past, expressing nationalist ideas, honoring life, confronting evil, and encouraging reconciliation. Do you see any of these goals reflected in the memorials in the visual essay? What other goals might these memorials reflect?

4. What are James Young’s criticisms of memorials? Do any of the memorials in this visual essay reflect his concerns?

5. What memorials and monuments do you pass in your daily life? Do they have an impact on you? Why or why not?

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising Memorial, Western Side

This memorial was designed by Leon Suzin and sculpted by Nathan Rapoport. Its western side depicts Jewish partisans who fought in the Warsaw ghetto uprising of 1943.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Sylvia Kramarski Kolski

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising Memorial

This memorial was built on the site of Warsaw’s Jewish ghetto. When it was unveiled in 1948, the city still lay in ruins all around it.

Hank Walker / Getty Images

Aschrott Fountain

In Kassel, Germany, artist Horst Hoheisel created a “counter-memorial” marking the site where a majestic fountain built by a Jewish citizen once stood; it had been destroyed by the Nazis in 1939.

EPA European Pressphoto Agency b.v. / Alamy Stock Photo

Stolpersteine

Stolpersteine (stumbling stones) in Sušice, Czech Republic, mark the site where the four members of the Gutmann family lived before they were murdered in the Holocaust. (See Reading 16, “Remembering the Names.”)

Wikimedia, David Sedlecký, CC BY-SA 4.0

Memorial to Roma and Sinti Victims of National Socialism

This memorial in Berlin, Germany, was designed by Dani Karavan and opened in 2012. The triangular stone at the center of the pool holds a fresh flower, which is replaced every day.

Michael Brooks / Alamy Stock Photo

Garden of Stones Memorial, 2006

Sculptor Andy Goldsworthy created this memorial at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City in 2003. Small oak trees were planted by Holocaust survivors in a hole within each stone.

Photo by Melanie Einzig, courtesy of Museum of Jewish Heritage and Galerie Lelong

Garden of Stones Memorial, 2012

Nine years after this memorial was created, the saplings have grown into large trees whose trunks have become part of the boulders.

Photo by Melanie Einzig, courtesy of Museum of Jewish Heritage and Galerie Lelong

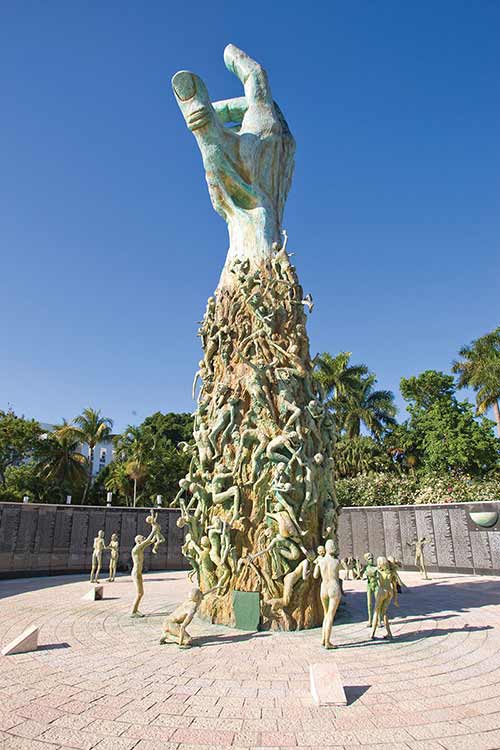

Holocaust Memorial Miami Beach

Miami Beach is home to a large number of Holocaust survivors, who commissioned this memorial by architect Kenneth Treister in 1990. The outstretched arm is almost four stories tall.

GALA Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Shoes on the Danube Bank Memorial

Sixty pairs of shoes mark the site in Budapest, Hungary, where fascist Arrow Cross militiamen shot Jews and threw their bodies into the river in 1944 and 1945. The memorial opened in 2005.

Wikimedia, Nikodem Nijaki, CC BY-SA 3.0

78 “Statement by Concerned Scholars and Writers,” Armenian National Institute, April 24, 1998, accessed June 3, 2016, http://www.armenian-genocide.org/Affirmation.22/current_category.3/affirmation_detail.html.

79 Raffi Khatchadourian, “Daily Comment: Remembering the Armenian Genocide,” New Yorker, April 21, 2015, accessed June 3, 2016, http://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/remembering-the-armenian-genocide.

80 Raffi Khatchadourian, “A Century of Silence,” New Yorker, January 5, 2015, accessed June 3, 2016, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/01/05/century-silence.

81 Facing History and Ourselves, “Taner Akçam: Why Is the Armenian Genocide Important?” (video), accessed June 3, 2016, https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/video/taner-ak-am-why-armenian-genocide-important.

82 Ian Buruma, The Wages of Guilt: Memories of War in Germany and Japan (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1994), 202.

83 Martha Minow, Between Vengeance and Forgiveness: Facing History after Genocide and Mass Violence (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1998), 141.

84 “Holocaust Monuments and Counter-Monuments: Excerpt from Interview with Professor James E. Young,” May 24, 1998, Yad Vashem, accessed June 3, 2016, http://www.yadvashem.org/odot_pdf/Microsoft%20Word%20-%203659.pdf.

85 James E. Young, “Memory and Counter-Memory,” Harvard Design Magazine, Fall 1999, accessed June 3, 2016, http://www.harvarddesignmagazine.org/issues/9/memory-and-counter-memory.

86 Quoted in ibid.