Reading 16

Imperialism, Conquest, and Mass Murder

In the late 1800s, European nations were competing fiercely for control of Africa, the only continent (other than Antarctica) that had not yet been colonized by Europeans. Some European imperialists, such as French leader Jules Ferry (see Reading 15, “‘Expansion Was Everything’”), justified the conquest by claiming that “superior races” had both a right to the territory and a duty to “civilize” the “inferior races” that made up the indigenous people of Africa. Others claimed no duty at all toward the indigenous people. Historians David Olusoga and Casper W. Erichsen explain:

The white races had claimed territory across the globe by right of strength and conquest. They had triumphed everywhere because they were the fittest; their triumphs were the proof of their fitness. Whole races, who had been annihilated long before Darwin had put pen to paper, were judged to have been unfit for life by the very fact they had been exterminated. Living people across the world were categorized as “doomed races.” The only responsibility science had to such races was to record their cultures and collect their artifacts from them, before their inevitable extinction.

The spread of Europeans across the globe came to be regarded as an almost sacred enterprise, and was increasingly linked to that other holy crusade of the nineteenth century—the march of progress. Alongside the clearing of land, the coming of the railroad, and the settlement of white farmers, the eradication of indigenous tribes became a symbol of modernity. Social Darwinism thus cast itself as an agent of progress.49

Along with Belgium, England, France, and Portugal, Germany was one of many European nations deeply influenced by Social Darwinism. It affected the way the nation justified its actions in South-West Africa (modern-day Namibia), where Germans occupied the land of indigenous groups, including the Herero and Nama, beginning in the 1880s. Within 20 years, German settlers not only occupied much of the land but had also acquired (through confiscation or purchase) more than half of the Herero people’s cattle. Cattle were central to the Herero culture and economy.50 Theodor Leutwein, the governor of German South-West Africa, explained what had happened to the Herero and Nama from an imperialist point of view when he wrote: “The native who did not care to work, and yet did not want to do without worldly goods, eventually was ruined; meanwhile, the industrious white man prospered. This was just a natural process.”51

When the Herero, the Nama, and other groups in the region fought to keep their land and resources, German leaders were outraged. The Herero, led by their chief Samuel Maharero, began to revolt in January 1904. Though they had much better weapons than the Herero, German soldiers were unable to quickly end the rebellion. They lost hundreds of soldiers to disease, the unfamiliar desert climate, poor supply lines, and ambush attacks by Maharero’s soldiers.52 German officials in both Africa and Europe were made furious not only by the uprising but also by the idea that an “inferior” people were challenging their authority.

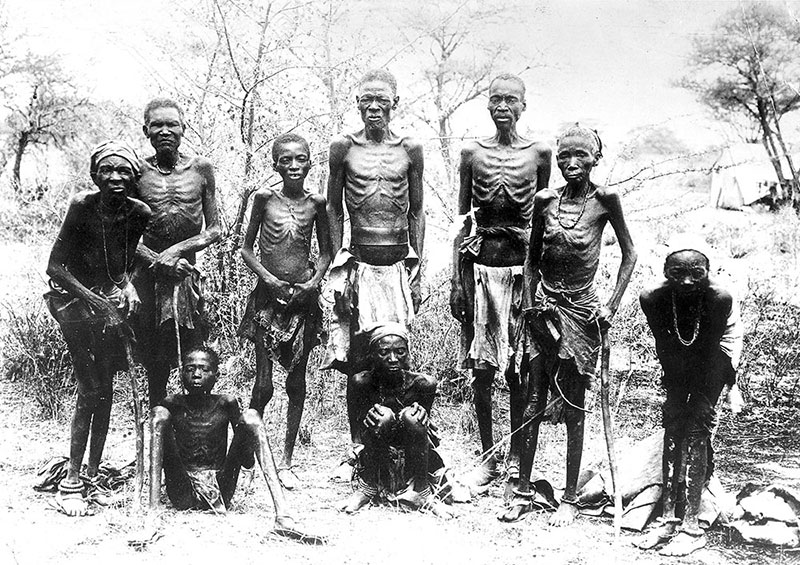

After the Germans drove the Herero into the Kalahari Desert in South-West Africa in 1904, the few that survived returned from the desert starving.

akg-images / ullstein bild

In August, Kaiser Wilhelm sent German Lieutenant-General Lothar von Trotha to take control of the colony and to “crush the rebellion by all means necessary.”53 Von Trotha had been previously stationed in east Africa, where he had a reputation for brutality in his efforts to put down all resistance to German rule. Von Trotha vowed to “annihilate the revolting tribes with streams of blood.”54

Aware that large numbers of Herero warriors and their families were congregating on the nearby Waterberg Plateau, von Trotha ordered his troops to attack not only the warriors but also their wives and children. They were to take no prisoners. The troops quickly surrounded the Herero on three sides. They left open the fourth side—the Kalahari Desert. To make sure that no one used it to escape, soldiers were ordered to poison all water-holes and set up a chain of guard posts in the desert.

On October 2, long after thousands of Herero had already been murdered, von Trotha issued an “Extermination Order.” It stated:

The Herero people must leave the land. If they do not do this I will force them with [big guns or cannon]. Within the German borders, every Herero, with or without a gun, with or without cattle, will be shot. I will no longer accept women and children. I will drive them back to their people or I will let them be shot at. This is my decision for the Herero people.55

Before von Trotha arrived in South-West Africa, historians estimate the territory was home to between 70,000 and 80,000 Herero. Most of them were killed at the Battle of Waterberg or by trying to escape through the desert. Only 20,000 to 30,000 remained in South-West Africa. Most of them were sent to labor camps and forced to work for German authorities. Conditions in the camps were so brutal that nearly half died.56

In 1907, following increasing criticism in Germany and abroad, von Trotha’s mission was canceled and he was sent back to Germany, where he was honored by the military. The shift in policy came too late for the Herero. Only 15,000 remained alive. It also came too late for the Nama people. After the defeat of the Herero, the Nama also revolted, and they too were swiftly defeated by von Trotha’s forces. On April 22, 1905, he ordered them to surrender or “be shot until all are exterminated.” He reminded them that if they continued to rebel, they would be treated in much the way the Herero were. Of an estimated 20,000 Nama, about half were murdered and the rest confined in work camps. Historians have explained the genocide in German South-West Africa as a result of Social Darwinist thinking, embodied especially in von Trotha’s idea of race war, combined with the German military’s institutional culture of extreme violence.57

The German atrocities against the Herero and Nama were not unique; similar attacks were made by British settlers against Aboriginal Tasmanians in Australia in the nineteenth century and by American settlers against the Yuki in California around the turn of the twentieth century. Contemporary historians call these episodes—in which an imperialist country intentionally tries to annihilate an indigenous people in order to control their land and resources—frontier genocide.58

Connection Questions

1. Describing the actions of Germans in South-West Africa and other similar historical cases, historian Benjamin Madley writes:

Victors write history, and . . . perpetrators create a myth to excuse their crimes. By claiming that so-called “primitive” peoples and cultures are fated to vanish when they come into contact with white settlers, a deadly supposition emerges: the extinction of indigenous people is inevitable and thus killing speeds destiny.59

What myths did Germans use to explain their attempts to annihilate the Herero and Nama? What motives did these myths attempt to excuse?

2. What is “the march of progress”? What did progress mean to imperialists?

3. In what kinds of situations have you used or heard the word exterminate? What is the significance of the way von Trotha used this word in describing his plans in South-West Africa?

4. What questions does the history of imperialist conquest and violence raise for you? In what ways is such brutality unexplainable?

49 David Olusoga and Casper W. Erichsen, The Kaiser’s Holocaust: Germany’s Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism (London: Faber & Faber, 2010), 73.

50 Benjamin Madley, “Patterns of Frontier Genocide 1803–1910: The Aboriginal Tasmanians, the Yuki of California, and the Herero of Namibia,” Journal of Genocide Research 6, no. 2 (June 2004): 182.

51 Ibid., 169.

52 Madley, “Patterns of Frontier Genocide 1803–1910,” 185–86.

53 Ibid., 186.

54 “The Herero Uprising 11 January 1904,” Namibia-1on1.com, accessed March 23, 2016, http://www.namibia-1on1.com/herero-uprising.html.

55 Lothar von Trotha, “Proclamation 2,” October 2, 1904, quoted in Olusoga and Erichsen, The Kaiser’s Holocaust, 149–50.

56 Madley, “Patterns of Frontier Genocide 1803–1910,” 188.

57 Isabel V. Hull, Absolute Destruction: Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005), 5–6; Jürgen Zimmerer, “Annihilation in Africa: The ‘Race War’ in German Southwest Africa (1904–1908) and Its Significance for a Global History of Genocide,” GHI Bulletin, no. 37 (2005): 51–57.

58 Madley, “Patterns of Frontier Genocide 1803–1910,”167–68.

59 Ibid., 168.