On June 3, the men of H Company, 2nd Battalion, 12th Infantry crammed into one of the thirteen LCIs in Plymouth Harbor, the same port Sir Francis Drake had sortied from to engage the Spanish Armada. Once the regiment completed embarkation, the LCIs cleared the port and slipped out to the English Channel on the evening of June 3. In the Channel, they joined the LSTs transporting the regiment’s vehicles and heavy equipment and, with them, sought temporary shelter in bays and coves along twenty-five miles of the rugged shoreline between Salcombe and Torquay. Thousands of similar vessels, each packed with men and materiel, huddled near shore across the southern English coast and waited for their respective convoys to form. One of the men in the Intelligence and Reconnaissance (I&R) Platoon, Carmen D’Avino, occupied himself painting watercolors of the peaceful, verdant Devon coast where the sea had sheared off the gently rolling farmland into a cragbound shore.1

On June 4, gale-force winds whipped the sea into a boiling chop, and pelted the ships anchored offshore with rain. The severe weather made an invasion on June 5 impossible. However, meteorologists on Eisenhower’s staff felt confident enough about a possible break in the bad weather to recommend that the operation be postponed rather than cancelled outright.

Bill and his men spent June 4 trying to stay dry as their ship bobbed up and down. The constant jostling nauseated the troops, and a few started throwing up. More followed. Soon the stench of vomit thickened so much that everyone succumbed to the heaves. Topside or below deck, no one could escape the smell. If a man put anything into his stomach, it wound up on the deck a short time later.

As night fell, the troops tried to sleep off the seasickness. If they were going to be miserable, they might as well rest while retching. Bill wedged himself into a space on one of the decks and managed to doze off. He awoke the next morning to the sight of his boots floating. My God! We’ve sprung a leak! Bill jerked himself upright, and franticly looked around to see what had happened. It took him a moment to realize that his boots were floating in vomit, not seawater. A second later the ship rolled, and the tide of spew swept to the other side.

In the mid-afternoon of June 5, word flashed to the invasion fleet. Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) had made its decision. “D-Day is June 6. H-Hour is 0630.” The escorting warships started to organize the convoys. The packed LCIs formed up in Lyme Bay under the direction of Rear Admiral Don P. Moon in USS Bayfield. For the men, the knowledge that their shipboard ordeal was coming to an end helped offset any fear they had of the approaching battle.2

The 4th Infantry Division and the rest of the force set to attack Utah Beach formed Force U. The ships steamed due east in twelve long columns that stretched to the darkening horizon. South of Weymouth, Force U joined the Omaha Beach convoy (Force O) to form the Western Task Force. Under cover of darkness, the long line of ships passed through the German minefields following lanes cleared by minesweepers. They steamed into their designated assault areas shortly before dawn.3

Looking out from their LCIs in the pre-dawn twilight, the men could see ships in every direction. The invasion fleet seemed to fill the entire English Channel. “A water spectacle more breath taking and awe inspiring than any of us had dared to imagine greeted our eyes. There were battleships and cruisers, destroyers and gunboats, corvettes and landing craft of all sizes, service ships, hospital ships, tug boats, dispatch boats, coast guard rescue cutters and miscellaneous vessels of every description. There were tankers full of high-test gasoline, LCIs full of seasick infantrymen, LSTs full of tanks and trucks.”4

Around 0550 hours (H–40 Minutes), the pre-invasion aerial and naval bombardment began. Several hundred B-26 medium bombers rained bombs on German gun emplacements within range of Utah Beach. Battleships and cruisers of the Western Task Force lobbed 14”, 8”, and 6” shells at the German defenses behind the beaches. Destroyers and rocket ships drenched the coastal defenses with even more suppressive fire. The bombardment was short, fierce, and successful. German gun batteries up and down the Cotentin Peninsula remained mostly silent as the first waves hit Utah Beach. At the actual landing site near la Madeleine, the main German strongpoint had taken several hits that befuddled the defenders.5

The 4th Infantry Division’s 8th Infantry Regiment landed at 0630 hours, followed by the 22nd Infantry, then the Twelfth. Despite the safe passage to the beach, both the primary and secondary control vessels for Utah Beach were lost, one to a mine, the other to mechanical trouble. Without the radar on these vessels to guide them, the landing craft of the initial waves drifted almost a mile south of the intended objective and hit the beach at la Madeleine. Instead of having two causeways (Exits 3 and 4) leading from the beach to the interior, the landing site had only one road over the inundated area (Exit 2).

The news was not all bad. The 8th Infantry landed at a weakly defended stretch of the beach, and the troops quickly overwhelmed the defenders. The Assistant Division Commander, Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr., had landed with the first wave and conferred with the battalion commanders on the beach. They debated whether to bring the succeeding waves to la Madeleine or shift them to the designated objective. Roosevelt reflected for a moment then announced, “We’ll start the invasion from right here!”6

The 12th Infantry’s convoy arrived off Utah Beach around 1030 hours. Men craned their necks to get a glimpse of the French coast, but they could see only a murky shore clouded by mist and dust. Countless barrage balloons floated above the gloomy horizon, each one tethered to a landing craft. Above the sound of the waves beating the ships’ sides, the men could hear an occasional crump as German artillery shelled the beach. LCMs and LCVPs pulled alongside the taller LCIs, and the men began to clamber into the assault boats. The crew of Bill’s LCI threw a cargo net over the side that reached into the holding space of his LCM. The boat’s crew pulled the net taut to give better support for the men to step on the horizontal lines, but the small ships bounced on the waves and the net would slacken then tighten to no particular rhythm. The men had been trained to grasp the vertical lines with both hands when stepping down, and that kept them from falling. With difficulty, thirty-plus men from H Company loaded into Bill’s LCM.7

The smaller boats marshaled into their assault waves by running in large circles through the swells. When the Wave Commander felt satisfied that all the LCMs and LCVPs had finished loading, he started the run to the beach. Jammed into the boat and tossed about on the open water, the men suffered yet another round of seasickness. By the morning of June 6, they had gone two days without being able to properly digest food. It was an awful way to enter a fight—sick, wet, and weakened by hunger.

Bill double-checked his men to make sure they were ready for action as the LCM surged toward shore. Most had the determined look of soldiers girding themselves for battle, but one man seemed upset and unnerved. Bill went over to the soldier, hoping to calm him. “Are you okay?”

“I’m just a little jumpy.”

Each wave or sudden noise made the nervous soldier flinch. Bill tried his best to ease the man’s fears. “Look, this whole thing is probably just another training exercise.”

A couple seconds later a German artillery shell exploded beside the LCM, sending shrapnel whizzing overhead and showering the troops with a column of seawater. Instinctively, every man hunched over until the effects of the blast subsided. The nervous soldier glared from underneath his helmet at the lieutenant. “Just another training exercise? Hah!”8

The LCMs and LCVPs formed on line and raced toward shore. As the water became shallow, the waves grew higher. Each wave jolted the boat and sent spray over the ramp. The coxswain steered the LCM toward a landing spot and ploughed the rising surf at a 90-degree angle. The boat caught a wave inside the breakers and rode it toward the beach, much like a man on a surfboard. A few seconds later, the LCM ran aground. The forward crew removed the safety pawl from the ramp’s gears, and the ramp clanked down until it smacked the surface of the water.

The troops pushed forward to disembark. The first soldier to the end of the ramp stepped off and disappeared underwater. The rest of the men stopped short, some teetering on the edge of the ramp. Bill sloshed through the vomit and seawater to the rear of the LCM and shouted to the coxswain, “Raise the ramp. We have to go in farther.”9

The coxswain shook his head. “No, you get off here.”

“It’s too deep. Take her in closer to the beach.”

“No! I’m in command of this boat, and I say you get off here.”

Bill pulled out his .45 cal. pistol and pointed it at the coxswain’s head. “Like Hell! Raise the ramp!”

The coxswain quickly changed his mind. The crew cranked the ramp back to vertical and the coxswain gunned the engine. The small boat pushed itself off the bar it had run onto and moved forward to the actual beach. This time, the LCM properly grounded itself in shallow water off the Uncle Red portion of Utah Beach. The ramp dropped a second time and the men charged into the surf. After splashing through the waves, they ran onto the beach at 1130 hours, five hours after the first wave. Although soaked and scared, the troops still felt grateful to be on solid ground.10

Just then, more enemy artillery struck the beach. Bill watched the shell bursts lift sand and debris into the air then spray a semi-circular pattern of shrapnel against the surface of the water. He’d seen mortars and artillery shells explode many times in training, but it felt nerve-wracking to be on the receiving end. The reality of combat became clear in that instant—a guy can get hurt out here. A soldier could protect himself, somewhat, by moving quickly and taking cover but could do nothing about where the next enemy round struck—no sense worrying about it. Bill understood that cowards fret about getting shot, while real soldiers pay attention to the things they can control. He later said, “The best thing to do is rely on your training and do your job.” He rallied his platoon and shepherded them off the beach.11

One man, however, dropped to the sand and curled into a fetal position. Bill ran over to him. “Let’s go! Get up!” he ordered. The man just shivered. More artillery rounds burst around them sending smoke, sand, and shrapnel into the sky. “Come on. It’s not safe to sit here,” Bill urged. “We gotta get off the beach.” The man refused to budge. Fear had turned him insensible. Bill gave up and left the man cowering on the beach for the medics to round up.

The engineers had blown a gap through the sea berm and linked Utah Beach’s exit to Causeway 2. The mortar platoon scurried up the sand incline and emerged into the open area behind the beach. There, General Roosevelt shouted instructions on which direction they needed to march.12

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. was the larger-than-life son of an even more renowned icon whose image had already been carved on Mount Rushmore. Known as “Ted” by his friends and “General Teddy” by his troops, he had already accomplished much in an amazing career: graduated from Harvard, earned a fortune in business, became a war hero in World War I, held a series of high government posts, and lost an election for the governorship of New York. In April 1941, he returned to active duty, received a star, and fought in North Africa and Sicily. Brave to the point of recklessness, General Teddy earned the respect and admiration of the troops he led. Unfortunately, his carefree attitude about military formalities and his casual dress, characteristics he shared with the division’s unorthodox commander, Major General Terry Allen, irked his senior commanders, Lieutenant Generals George S. Patton and Omar Bradley. Bradley relieved Allen and Roosevelt in an effort to tighten discipline within their battle-weary division.

Not wanting to let a talented combat leader go to waste, Eisenhower scooped up Roosevelt from the Mediterranean Theater and assigned him to the Ivy Division as its assistant division commander. Roosevelt’s courage and decisive leadership on Utah Beach would earn the Medal of Honor and confirm the wisdom of Eisenhower’s decision.

Bill immediately recognized Roosevelt. He stood out even more that day because of his devil-may-care demeanor, armed only with a cane. Bill noticed something else about Roosevelt’s appearance—he had removed his helmet and wore just a soft cap on his head. Worried about the example he was setting for the enlisted men, the young lieutenant approached Roosevelt. “Sir, you’re not wearing your helmet. We have strict orders for everyone to keep their helmets on at all times.”13

Teddy smiled. “Yeah, but I’m a general.”

In retrospect, it seems odd that Bill would be the one to admonish a general about wearing a helmet because he had his own peculiar habits about headgear. Most soldiers wore their helmets to shade their eyes and cover their foreheads. Bill hated having anything covering his eyes, so he pushed his helmet back on his head. This habit gave Bill what some might have considered a casual, unprofessional appearance, but he did not care as long his vision was not hindered.

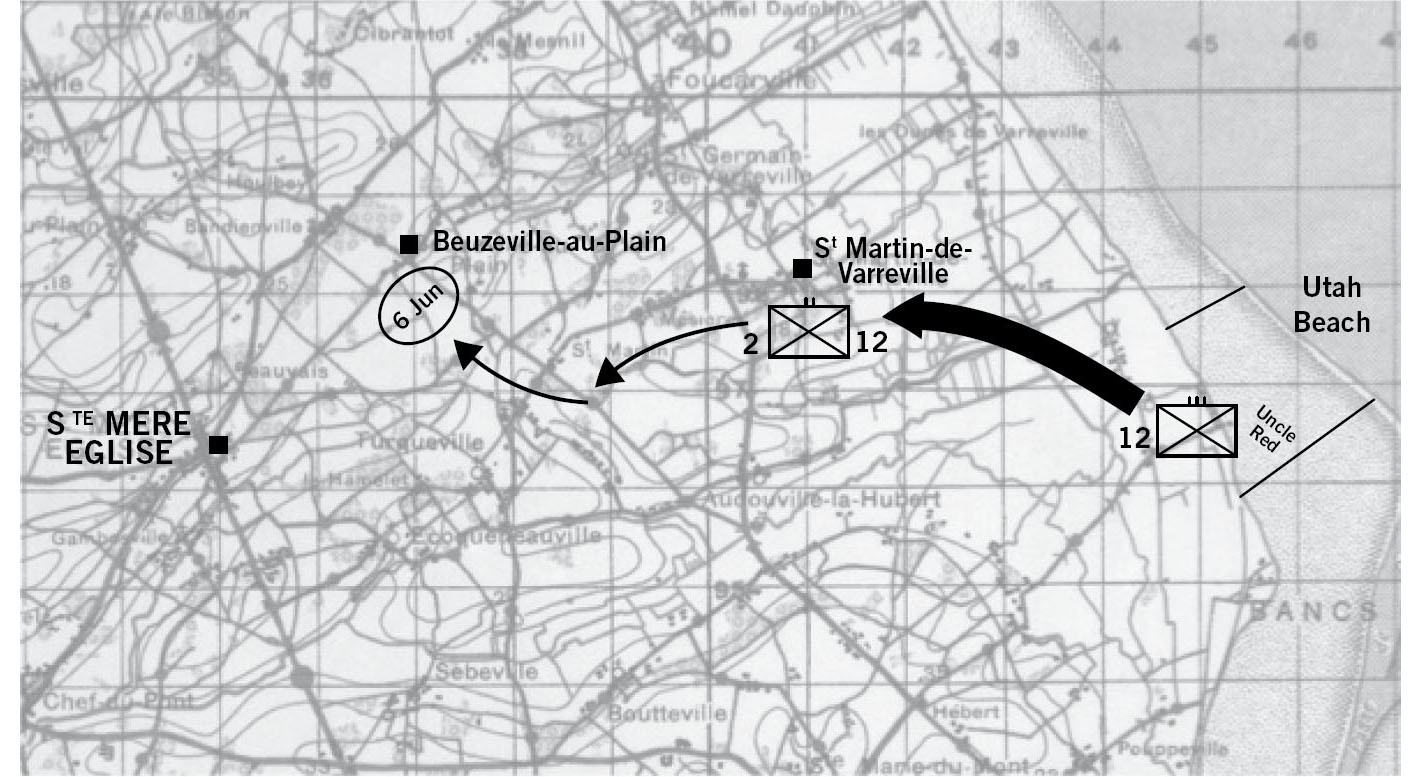

The division’s original plan called for the 8th Infantry to hook south to secure the beachhead’s left flank and the 22nd to slice northwest to hold its right. The 12th Infantry had intended to use Causeways 3 and 4 to drive up the middle and link up with the 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment near St. Martin-de-Varreville. Because the division landed at la Madeleine, the initial waves went straight inland on Causeways 2, 3, and 4, jamming them with men and equipment. To get around the traffic, the 12th Infantry advanced northwest from la Madeleine across three miles of the inundated area. The mortar platoon was supposed to have seven jeeps and trailers to move its weapons and ammunition but none of them were available after the landing. The mortarmen shouldered their tubes, base plates, bipods, and rounds, then started slogging along a narrow path away from the beach. Just beyond the dunes they passed a German soldier lying face down by the side of the trail. Bill stared at the corpse as he walked by. He had never seen a dead man before. A short distance past the body, the route of march angled toward St. Martin-de-Varreville and slipped into the swampy ground.14 (See Map I)

This was the part of the D-Day operation that troubled Bill the most. The low-lying terrain behind the beaches created a shallow moat along the Cotentin’s eastern coast. If the Germans dumped gasoline into the water, the fuel could spread for miles over the surface. Twelve square miles might explode into flames at the strike of a match, turning the water obstacle into a fiery death trap. Bill checked for any signs of gasoline. Much to his relief, he saw no evidence that the Germans had poured any into the marshland. Either the German defenders hadn’t thought of the tactic or considered it a poor use of precious fuel.15

The flooded zone may not have burst into flame but the men still had to wade through waist-deep pools laden with heavy combat loads and life belts. The Germans had dug ditches in the low-lying terrain before flooding it. The unfortunate infantryman who first stepped into one of these submerged trenches would suddenly find himself two feet under water. This threat was especially real for the heavily burdened men of the mortar platoon. Bill’s platoon leader commented, “Sometimes we’re in shallow water and sometimes we’re swimming.” Colonel Reeder had warned the men of this danger. He instructed everyone to keep his life belt on and pair with a march buddy who could pull him up if he fell into a water trap. Reeder’s sensible precautions and good training paid off. The regiment climbed out of the boggy terrain around 1300 hours near St. Martin-de-Varreville without losing a single man or weapon. The colonel felt elated by that accomplishment. “I knew then that we were going to win the war!” he later said.16

After linking up with the paratroopers and reorganizing the regiment, Colonel Reeder ordered the 12th Infantry’s first attack to proceed at 1330 hours. The infantrymen pushed west then southwest, using the road running between St. Martin-de-Varreville and Les Mezieres to guide its avenue of advance. Lt. Col. Dominick Montelbano’s 2nd Battalion took up position on the south (left) side of the road and surged ahead against remnants of the 919th Infantry Regiment of the 709th Division, a static coastal defense unit of questionable quality. Caught between the paratroopers and the 12th Infantry, the German defenders fractured into small elements and managed to put up only a poorly coordinated defense.17

Montelbano apportioned the two heavy machine gun platoons out to the two lead companies but kept the mortar platoon in general support of the battalion. Bill’s mortar crews mostly followed behind the battalion’s riflemen as they cleared the enemy pockets of resistance and the occasional sniper. They did not have to assault the few defenders, but keeping pace with the riflemen while shouldering their heavy loads (the base plate, bipod, and mortar tube each weighed about forty-five pounds) posed a big enough challenge.18

The Ivy Division soon encountered the distinctive feature of the Norman bocage countryside—hedgerows. For centuries Norman farmers had marked the perimeters of their fields by mounding dirt and planting hawthorn and hazel shrubs on top of the earthen walls. In time, the hedgerows had grown in height and density to become serious impediments to any advance. During their pre-invasion planning, SHAEF’s staff had not considered how hedgerows might affect operations, so Allied units had not trained to fight in the bocage. Against light resistance, the hedgerows merely slowed their advance. As the men of the Ivy Division and other units soon would learn, hedgerows would pose formidable and deadly obstacles when properly defended.19

The rifle platoons swept west, eliminating snipers and overwhelming the occasional German machine gun nest with help from the 81mm mortars. Lieutenant Slaymaker, the mortar platoon leader, recalled a close call during one encounter. “In going across an apple orchard a sniper takes a shot at me. I duck behind a tree and try to locate the source. I see nothing and there is no more firing, so I make a dash to the next tree. I am shot at again and almost at the same time I hear the crack of an M-1 and a German in a camouflage suit comes tumbling out of a tree at our left. My instrument Cpl. has gotten #1 for himself.”20

The 12th Infantry followed the road for about two miles past Les Mezieres to an intersection short of the hamlet of Reuville. Colonel Reeder directed his two lead battalions to angle northwest from the intersection with Colonel Montelbano’s 2nd Battalion again marching on the left side of the formation abreast of the 1st Battalion. At this point, the lead platoons began to contact paratroopers from the 82nd Airborne Division, some of whom were hopelessly lost. The linkup between the two divisions fulfilled one of General Barton’s key missions for D-Day.21

The regiment advanced another mile to Beuzeville-au-Plain, where the 1st Battalion wiped out an enemy strongpoint and captured a German 75mm anti-tank gun at the crossroads. Colonel Montelbano’s men pulled alongside their left flank then halted along the road running southwest from Beuzeville to Ste.-Mere-Eglise. They dug in for the night. The battalion’s E and G Companies fronted the road with F Company a couple hundred meters behind them, the classic “two up-one back” defensive formation. For its part, H Company dug in another three hundred meters behind F Company.22

H Company spent the rest of the evening preparing a defense. Bill had plenty of tasks to handle after the battalion settled in place. According to Army doctrine, “The section leader makes such forward reconnaissances [sic] as are necessary to identify registration points and target areas, and to prepare firing data. He ascertains the location of the main line of resistance and nearby rifle units…Within the firing position areas assigned by the platoon leader, the section leader selects the location for each mortar. Each firing position should be defiladed and concealed, and must be within communicating distance of the observation posts…At least one alternate firing position is selected for each mortar…An observer remains at the observation post. The section leader indicates the sector of fire to the corporal by pointing out definite terrain features.” After receiving Bill’s instructions, the crews set their mortars up for the planned missions. The section ran telephone wire to the observers to ensure speedy calls for fire if the enemy hit the battalion front in the dark. To help the guns fire swiftly when needed, the squad leaders recorded the descriptions, locations, and firing data for their primary and secondary targets on “range cards.” Bill turned these range cards over to Lieutenant Slaymaker, so he could sketch the mortar platoon’s target overlay.23

That evening, Horsa and Waco gliders flew in to deliver artillery, anti-tank guns, jeeps, and support troops to the interior of the Cotentin Peninsula. The glider pilots used the twilight glow of the setting sun and the illumination from a full moon to search for suitable landing sites near Ste.-Mere-Eglise. German anti-aircraft fire made the task of landing even more perilous. Lieutenant Slaymaker recalled how the mortar platoon jumped into action. “We can see just where their fire is coming from so we open up on them with the mortars; then there is no more fire from that spot.” The pilots did their best to maneuver their gliders and avoid the enemy fire, yet several crashed into open fields near the 12th Infantry. “That was a pitiful, bloody thing to see and hear,” a member of battalion HQ recalled. The battalion sent out patrols to assist the glider-borne troops. Bill and his men found a few wrecked gliders with dead paratroopers next to them. The sight saddened the young lieutenant. There lay brave, well-trained men who died before even making it into the fight.24

After preparing defensive fire missions, the now-exhausted men dug the foxholes in which they’d spend their first night in France and, hopefully, catch some sleep between sporadic episodes of enemy fire and probing. Even with the ever-present danger, the men experienced a general emotion of relief that they had established a foothold in France—and that they had survived D-Day. As one battalion soldier said, “Now we felt we had a chance to live a little longer.”25

Higher headquarters felt more than relief. The Ivy Division had successfully landed and deployed all three of its regiments with only light casualties. The division’s progress, strength, and fighting disposition convinced Maj. Gen. Lawton Collins, commander of VII Corps, and Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, the First Army commander, that the right flank of the invasion force was secure. The assault on Utah Beach had been considered the most precarious of the five D-Day landings, but it made the deepest advance with the fewest losses. By evening, roughly 21,000 men, 1,700 vehicles, and 1,700 tons of material had poured across the sand of Utah Beach. Strengthened by this surge, the lodgment on the Cotentin Peninsula rapidly solidified.26