Bill arrived at the Royal Army Medical Corps’ 83rd General Hospital in Wrexham, Wales. There, the medical staff cleaned his wounds from the rocket blast. He was in bad shape in other ways, too. In the days since D-Day, the vomit and sea salt had been flushed out of his uniform by sweat, rainwater, dirt, and dried blood. Bill had not had his boots off for several days. When nurses removed his socks, the soles of his feet peeled off like paper stuck to adhesive tape.

After cleaning his external wounds, the doctors studied x-rays of Bill’s chest to assess the danger posed by the embedded shrapnel. One piece measured three-quarters of an inch in diameter. They saw that his ribs were cracked but failed to notice that his eardrums had been ruptured, too. The punctures in his back worried them most. The doctors decided to leave the chunks of steel in his torso rather than risk further injury trying to dig them out. The hospital staff gave him oxygen, blood transfusions, and fifty-two doses of penicillin over a week. “God, there are holes all over my arms,” he complained. Bill responded well to the treatment. Once he got some rest, his breathing became less painful and he gradually regained his strength. In time, he could focus on things besides his soreness.1

He first thought about alerting Beth. Like everyone else on the home front, she was thrilled by the news of the Normandy landings but had no way of knowing that Bill had entered combat. Bill knew that the War Department would soon notify her by telegram that he had been wounded. He dreaded the idea of Beth receiving such a telegram unaware. It would certainly put her through a moment of severe anguish until she had a chance to read it. Even after learning that he was not dead, she would still be left to worry about the extent of his wounds. As soon as he was able, he sent an urgent V Mail to tell her that he had been wounded and shipped to a hospital. Bill downplayed his injuries. “There are actually 5 holes in me but you know that I’m too tough to be seriously hurt.” He went on to mention that the scars would be on his back. “No, I was not running away.” Thankfully, his letter arrived before the War Department telegram. Despite the serious nature of Bill’s wounds, Beth felt relieved to know that he was alive and would recover.2

While in the hospital, Bill noticed the strange scrape on his hand. It did not fit with his wounds from the German rocket. Thinking back to the battlefield, he remembered falling asleep on his way to a company meeting and cutting his hand on a shrub. Then he recalled the uneasy feeling he had about getting wounded.

Bill, not the sort to believe in premonitions, put his faith in calculations, proofs, and evidence. He openly scoffed at spiritualists, ghost chasers, and followers of the occult. Yet, he could not deny that the strange sensation he felt the morning of June 9 foretold his wounding.

As he pondered this premonition, he remembered experiencing the same uneasy sensation on the day he left home. He had boarded a plane and looked back at his parents when he felt that he would never return. What did that premonition mean? Am I not going to make it back home? Bill felt a sudden grip of dread. Even if he did not believe in “extrasensory perception,” the premonition about not going home would trouble him until the end of the war.

As his body healed, Bill thought back on his brief experience in France. The short stint in combat seemed disappointing compared to the months of training and preparation for the invasion. “It makes me very angry to be a casualty after 4 days of fighting. I’ll be back there soon, though.” He did not blame himself for getting wounded but he had hoped to do more. Reflecting on his role in the war, one redeeming thought came to mind. “Remember why I wanted combat?” he wrote to Beth. “I wanted to see how I would react under the pressure of combat and danger. Well, I feel OK about myself now—the question has been answered now and I don’t have to admit to anything—thank God.”3

Bill spent the rest of June recuperating. The time passed slowly. He read, played checkers, and wrote letters to Beth. On June 26, he blew fourteen dollars on a bottle of rum and went out with a couple of other patients to celebrate his anniversary. The party turned out to be more bitter than sweet. He felt terribly lonely and regretted spending the money. When he had been brought to the hospital and stripped for surgery, someone stole his wallet. The government allowed Bill to draw seventy cents per day in casual pay but his mess bill ran ninety cents per day. Without cash or a blank check, he had to run up a debt for his meals in the hospital. Bill had to ask Beth to send money through the Red Cross. That depressed him even more. Bill had been short of cash during their entire courtship and he was not doing much better as a husband. “Our marriage has given me a goal, a purpose in life. It has given me something tangible to fight for. It has also given me a guilty conscience. So far I have given you nothing but an obligation.”4

The surgeons finally stitched his wounds shut. Bill warned Beth that he would leave the hospital in “a week or 10 days.” That meant a return to combat. Bill indulged in thinking ahead to life after the war. “Well darling, we will live a sensible life after we are together. We know what a precious thing a normal married life can be.” His patriotism mingled with his resentment against the Germans for the disruption wrought on his young life. Philosophically, he wanted to destroy the enemy’s country to prevent a future war, yet his sense of humanity weighed against retribution. “Who am I to say another man should be killed so that I will not have to fight again in 20 or 30 years? Life is very precious even though it is wasted.”5

Bill’s strength had returned by the first week of July but he still had not fully healed. Meanwhile, the heavy casualties in Normandy put pressure on the medical staff to return wounded men to duty as quickly as possible. Even though his wounds still had to be bandaged, the doctors cleared Bill for frontline duty.

Bill’s recovery left his body vulnerable to other health threats. Just as he got orders to return to France, one of his teeth became infected. In his weakened state, the infection developed into an abscess, causing a great deal of pain. The young lieutenant made an appointment with the dental staff to remove the infected tooth before he had to redeploy.

The dentist examined the abscess and agreed the tooth needed to be extracted. However, he saw a problem. “There’s so much pus in your abscess I’m afraid the pain killer won’t do any good,” he said. “We ought to wait for the swelling to go down.”

“I don’t care,” Bill replied. “The abscess is killing me already and I can’t come back tomorrow. We have to pull the tooth now.”

“I’m sending you back to the hospital for three days then you can come back.”

Bill reminded the dentist that as an officer with orders already detaching him from the replacement depot he did not have to comply with his instructions. The dentist relented and did what he could to sedate the lieutenant before prying out the infected tooth. The procedure hurt—a lot—but the abscess had been causing so much aggravation that Bill did not care. “What a relief that was. It had been aching all day and for spells all week.” The dentist sent Bill back to the officers’ quarters to sleep off the operation.6

The hospital staff assigned the recovering lieutenant an enlisted orderly, also known as a batman, as was customary for British officers. When Bill returned to the barracks, the batman had prepared his uniforms and personal gear for transport. The batman asked Bill what else he might need. “Wake me up when the mess hall is serving supper,” Bill answered then went to bed. The soldier later roused the sleepy lieutenant for the meal, after which Bill went back to sleep.

The British soldier came back the next morning to get Bill ready for the trip. Still groggy, Bill got up, boarded the train, and immediately fell back asleep. A few hours later the batman woke him again. “Sir, we’re about to arrive.”

After sleeping for most of the past twenty-four hours, Bill had finally gotten over the effects of the sedative and the tooth extraction. He thanked the batman for his services and boarded the ship. As he boarded, Bill could not help but wonder what kind of impression the British batman had of the American lieutenant who did nothing other than sleep.

The voyage back to France seemed strange and outlandish compared to the last time he had crossed the Channel. Then, he and hundreds of other men had been packed into a sea-tossed LCI smelling of puke. This time, he had a comfortable berth in officers’ quarters aboard a merchant vessel. Bill marveled at the “straight grain teak” appointed cabin. Service in the officer’s wardroom was equally lavish. “At mess we have a Laskar [sic] boy [servant of Indian extraction] for every table (7 offs.), and he practically breaks his neck waiting on us.” As much as Bill enjoyed the accommodations, something about them offended his sensibilities. “You know it is not typical British life here. Those that have wealth have plenty, but they are few.”7

Bill made his way forward to the front after landing in Normandy for a second time. By July 21, he reached a small village a short distance from the 4th Infantry Division sector. He knocked on the door of a French house to get out of a driving rain. The family readily agreed to let him spend the night. He slept with a roof over his head and out of the rain, a treat he would not enjoy for weeks to come. In his time with the family a few things about their culture and attitudes bothered Bill, particularly the way the farmers treated their women. Every time he requested anything, the French husband would agree then tell his wife to get whatever Bill wanted. “Speaking of the women. You know they do most of the work. You will see the woman pushing a wheelbarrow and her husband walking beside her smoking his pipe!!”

Bill rejoined H Company on July 22 in a soggy assembly area outside the hamlet of le Desert, thirteen kilometers northwest of St. Lo. The sudden reappearance of someone long since written off caused a stir within the unit, especially among the men who had seen the hole next to his heart. He had been one of their past-tense officers.8

As happy as he was to be back with his unit, the swarm of new faces and the many missing D-Day veterans dampened his spirits. The 12th Infantry had been through tough times during his convalescence. The VII Corps had driven the Germans back from Montebourg to Cherbourg in the two weeks after Bill had been wounded. The 12th Infantry helped capture the vital port on June 25. After achieving that strategic objective, the 4th Infantry Division moved south of Carentan to expand the Normandy beachhead. In ten days of brutal fighting, the regiment advanced a mere six kilometers, hedgerow-to-hedgerow, against elements of the 2nd SS Panzer “Das Reich” Division and the 17th SS Panzergrenadier “Gotz von Berlichingen” Division. The rest of the First Army fared no better. A determined German defense had kept the Allies bottled up in Normandy. General Bradley called off the broad-front push by the V, VII, VIII, and XIX Corps once St. Lo fell on July 18.9

The lack of American success can be partially attributed to the Army’s tactical doctrine in 1944. The operations manual visualized only two primary forms of attack: an envelopment and a penetration. The manual stated a preference for an envelopment, if an assailable flank was available; if not it called for a penetration. By penetration, the Army meant a rupturing of some point along the enemy’s front. “In a penetration the main attack passes through some portion of the area occupied by the enemy’s main forces and is directed on an objective in his rear.” The manual failed to emphasize a key characteristic of this type of operation—that an attack should strike as slender a slice of the enemy’s defenses as possible. It did recommend concentrating forces for the main attack but the guidance left a supposition that the attacking unit would still face the whole breadth of the defender’s line. Later, doctrine would draw a distinction between a penetration and a frontal attack, narrowing the definition of a penetration to a concentrated attack against a relatively narrow portion of the enemy’s defense.10

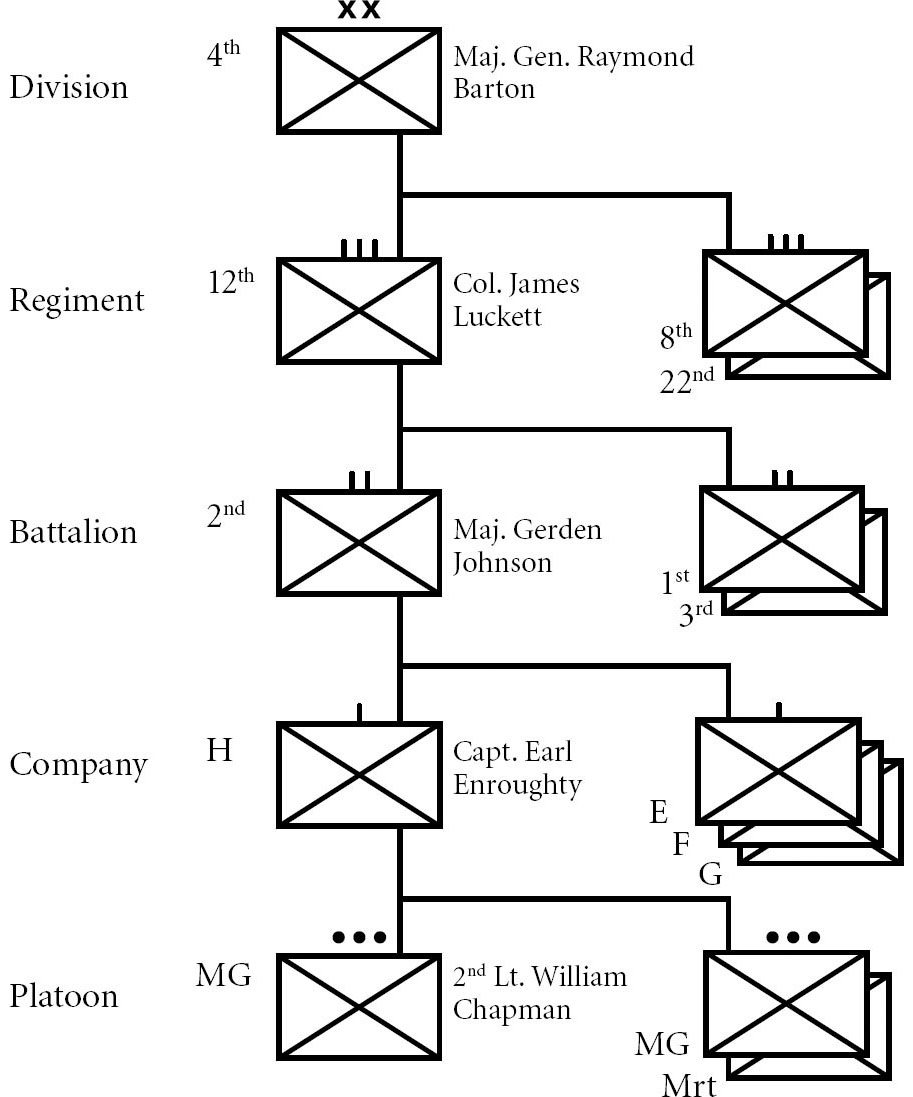

The early July battles took a savage toll on the Ivy Division. It had lost 2,300 men and radically changed the battalion’s officer roster. Tallie Crocker had returned from the hospital but had a new assignment. Captain Earl W. Enroughty, a dependable officer from Virginia, assumed command of H Company on July 20. Major Richard O’Malley took over the 2nd Battalion after Dominick Montelbano was killed outside Montebourg. O’Malley—known as “The Iron Major”—had infused the battalion with his aggressive fighting spirit, but he was killed less than a week before Bill returned. Major Gerden F. Johnson, the 1st Battalion’s executive officer (XO), took command in O’Malley’s place.11 (See Fig. 3)

Changes had occurred in the higher echelons, too. Colonel James S. Luckett, an unassuming but capable officer, replaced the dynamic Red Reeder as commander of the 12th Infantry. The division commander, General Barton, remained but the Ivy Division lost its beloved deputy commander, Ted Roosevelt Jr. The hero of Utah Beach died from a heart attack on July 12.

Captain Enroughty assigned Bill to lead one of the two heavy machine gun platoons in H Company. His platoon was organized into two sections, each equipped with two M1917A1 Browning .30 caliber water-cooled machine guns.

The M1917A1 heavy machine gun weighed thirty pounds and came with a six-pound water canister and fifty-three-pound tripod. This considerable weight made them too heavy for rifle companies, which were equipped with the lighter air-cooled M1919 machine gun. The Army placed the M1917A1s into machine gun platoons within the battalion’s heavy weapons company. Each of Bill’s four gun squads had its own jeep to haul the guns and their ammunition.

The two types of machine guns fired the same M2 cartridge, but each served a separate purpose. The lighter M1919 enabled the rifle companies to carry the firepower of a machine gun forward with its riflemen. The infantry prized the M1917A1 for its incredible reliability and indirect fire capabilities. The War Department purchased the M1917A1 after its inventor, John Browning, conducted a demonstration for senior officers and political leaders. He fired a single “burst” of 20,000 rounds from an M1917 without a pause or malfunction. The M1917A1 would go on to serve in the U.S. Army and Marine Corps well into the 1950s.12

Fig. 3 Organization Jul–Aug 1944

Machine guns were ideal for creating a final protective line (FPL), a defensive tactic meant to stop enemy infantry short of friendly positions by shooting a constant wall of lead across the front line. For them to be effective in the offense, the gunners had to fire either between advancing rifle squads or over their heads using indirect fire techniques, similar to the fire control methods used by the mortars.

Captain Enroughty also told Bill about a big upcoming offensive scheduled to jump off on July 24. General Bradley had abandoned the broad-front attack across the entire American portion of the Normandy line. He now planned to punch through a four-mile stretch of the German frontline with a concentrated attack using the VII Corps, which included the Ivy Division, as the strike force.

A straight length of an old Roman road running between St. Lo and Periers marked the LD for the attack. Beyond that line, bombers from the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces would saturate a target box with bombs to blast away the mixed elements of the Panzer Lehr, 5th Parachute, and 275th Divisions. Unlike the aerial bombardment that preceded the failed British Operation Goodwood, the Americans would use only bombs of 250 pounds or less to avoid creating massive craters along the planned line of advance. The plan also called for an immediate ground assault after the aerial bombardment to take maximum advantage of its shock effect. As soon as VII Corps penetrated the German front, several armored divisions would pour through the gap. Bradley hoped that this offensive, “Operation Cobra,” would achieve a breakthrough that would allow the armored forces to thrust deep into the German rear. General Barton designated the 8th Infantry Regiment as the Ivy Division’s spearhead with the 12th Infantry following it into the target box to mop up any pockets of resistance bypassed by the lead regiment.13

Rain fell for the next two days, forcing the postponement of the attack and giving Bill more time to get acquainted with his new platoon. On July 24, a few bomber squadrons that had taken off for the scheduled attack did not get the recall message and dropped their bombs, some of them “shorts” that killed a few American troops. The Americans worried that the abortive strike had tipped their hand, but the Germans did not react.14

When the men of the 12th Infantry awoke on July 25 and saw clear skies overhead, they knew Operation Cobra would proceed. Some took the opportunity to watch the massive preparation of the target box from the orchards six kilometers back from the St. Lo–Periers Highway. One of the riflemen in Bill’s battalion, Private Dick Stodghill, described the unfolding operation.

The artillery began firing at nine…Every gun within range was taking part…The barrage continued for an hour. Then came the dive bombers. This also seemed never-ending, but it finally stopped and then from behind us came medium bombers…At last it ended…some of us believed that the tank crews and infantrymen of Panzer Lehr had undergone enough pounding…But then…we heard a droning sound approaching from behind. [B]y looking almost directly overhead I saw them, dozen upon dozen of Flying Fortresses and Liberators so high that they looked like toys suspended below a blue ceiling.

[B]ut then the bombs began falling and in stunned surprise we turned again to face the front. For several minutes the thunderous roar of the explosions and the sights of huge clods of dirt flying high in the air drove every thought from mind. Then the idea came over me. No one deserved what the men on the other side of the road were experiencing.

Soon, though, the smoke and dust drifting back over us turned the sky dark. On the far side of the highway it seemed as black as night.

Then came the sickening realization that bombs were beginning to fall on our side of the highway…The explosions drew nearer and nearer until we could see that the bombs were falling on the 8th Infantry and in another minute would be falling down on us.15

A phenomenon called “creepback” caused the shorts. Bombardiers in the lead formations dropped their bombs a little short of the planned target. The clouds of smoke and debris obscured the targets for those in the following formations, who shifted their aiming points even closer to the American troops. As a result, the bombing crept back from the planned target with each successive bomber formation.

The short bomb loads hit the forward regiments but stopped just short of the 12th Infantry, though the shock waves still vibrated their pantlegs. The end of the bombardment around 1200 hours signaled the time to advance. The regiment pulled out of its assembly area thirty minutes later and marched south. By 1530 hours the 2nd Battalion approached a new assembly area south of le Hommet-d’Arthenay, still short of the St. Lo-Periers highway. There, the men rested, waiting for word on the 8th Infantry’s progress.16

News from the front did not encourage them. The short bomb loads disrupted the lead elements of the assaulting infantry divisions, especially the 4th and 30th. More than six hundred men were killed and wounded. Although the 8th Infantry’s four assault companies had suffered losses and probably needed time to reorganize, the order came down to launch the attack, regardless of the confusion. The only consolation for the still-dazed troops was the thought that the Germans must have suffered far worse, so the attack should face little opposition. The 8th Infantry advanced toward the highway across a devastated landscape. One of the attached tankers described the scene. “The ground was churned up, trees felled, dead birds and livestock everywhere about.” Before the 8th Infantry reached the LD, it ran into stubborn German outposts north of the highway. It took the firepower of B Company, 70th Tank Battalion to crush one of the outposts. The 8th Infantry barely made it to the old Roman road by 1600 hours. Up and down the line, the American infantry reported stiff, though sporadic, resistance.17

The initial reports coming back to First Army dismayed General Bradley. He had counted on a quick follow-up to the aerial bombardment that would hit the Germans before they could recover. Eisenhower, who had come to the First Army HQ to witness the event, left in a huff, angered by the friendly fire casualties and disheartened that another major Allied offensive failed to punch a hole in the German line.18

As the attack proceeded into the evening, evidence began to surface that Cobra had accomplished something. American infantry began picking up groups of German prisoners by 1655 hours. “[T]hese grenadiers from Panzer Lehr had been at the center of the air attack and now they stood slack jawed and uncomprehending as a result of concussion…They were bleeding from the mouth, nose, ears and even the eyes.” The 12th Infantry still had not moved into the target box but Bill ran into some captured Germans as he trailed behind the 8th Infantry while reconnoitering. “They were dazed and disoriented,” Bill recalled. “There was no fight left in them.”19

More encouraging information trickled back as the lead regiments drove deeper into the target box. At 1804 hours, a battalion of the 8th Infantry had been able to bypass a German pocket of resistance, something the Germans usually stymied. The 8th reached la Chappelle-en-Juger, at the center of the target box, at 2200 hours then consolidated for the night. Back at VII Corps HQ, General Collins noticed that the Germans had not counterattacked anywhere within the target box. The sustained fighting over the previous weeks had severely weakened the Germans and forced them into a defensive scheme that relied on a line of strong outposts supported by units that could conduct vigorous counterattacks when and where needed. The aerial bombardment had smashed most of the Germans’ reserves and obliterated their lines of communication, denying them the ability to mount effective counterattacks. Though the initial gains were relatively meager, Collins sensed that the German defense had cracked. He ordered a full exploitation by the infantry divisions and committed the two armored divisions he had in reserve, even though the criteria for launching them had not yet been met.20

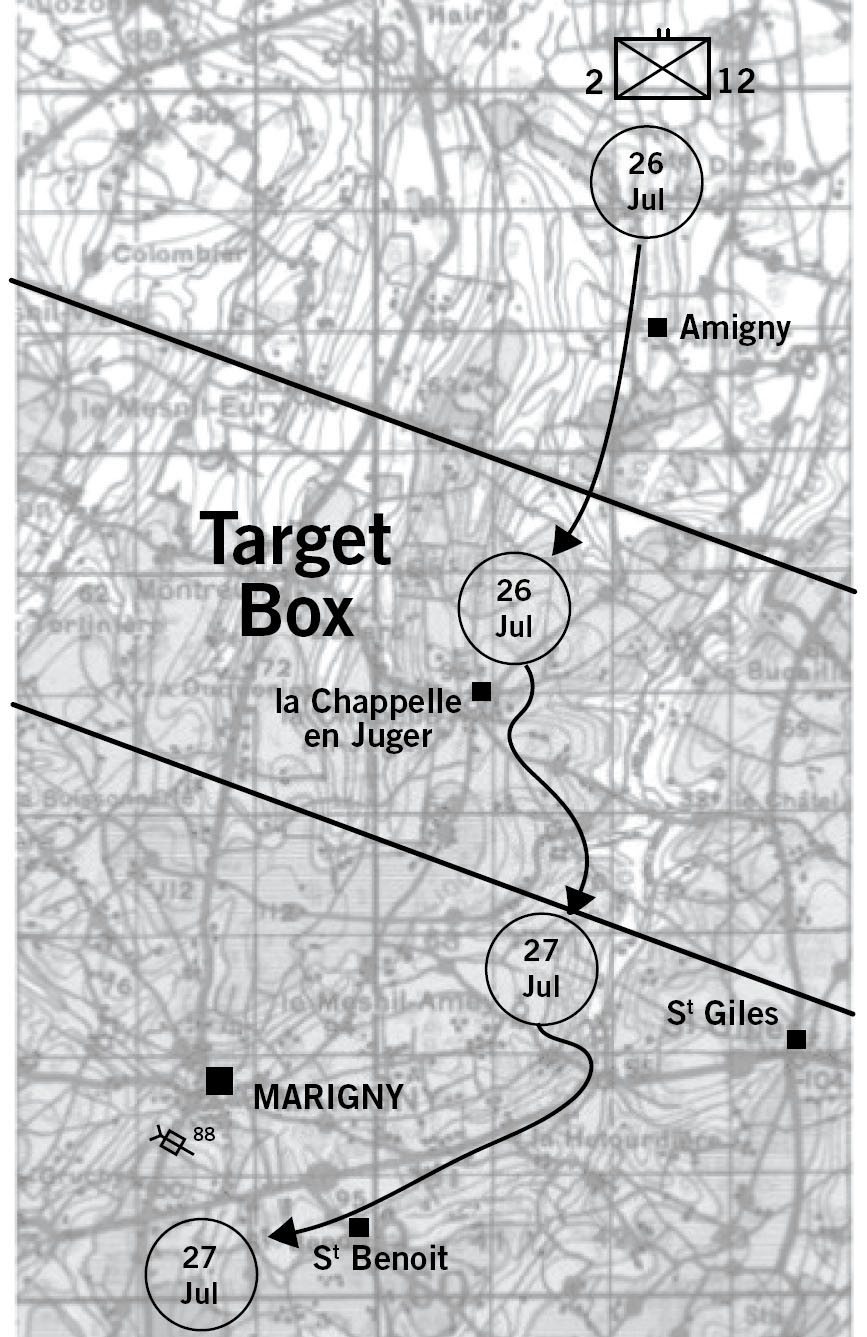

Orders came down from division just before midnight for the 12th Infantry to advance south of the St. Lo–Periers highway. The 2nd Battalion, in regimental reserve, began its movement shortly after 1000 hours on July 26 to occupy a position previously held by the 1st Battalion near the hamlet of Amigny, still north of the highway. The battalion waited throughout the afternoon for the next order to advance. Finally, Maj. Gerden Johnson led the battalion into the target box around 1845 hours after MPs helped clear a traffic jam on the highway.21 (See Map III)

The troops crossed over fields dotted with craters, each one surrounded by a splatter pattern of tossed earth and bomb fragments. The stench of rotting flesh hung in the air. German pockets of resistance persisted, so the men had to advance cautiously. The battalion attached Bill’s heavy machine gun platoon to one of the lead rifle companies because of the obscure enemy dispositions. Bill moved his platoon with the rifle company and scouted for potential firing positions. The gun crews humped their weapons, tripods, and ammunition while the platoon’s vehicles followed, usually one hedgerow back.22

It did not take long to run into the enemy. Small detachments of Germans still held their positions and fired on the Americans from behind hedgerows. These isolated enemy detachments lacked cohesion, and the American infantrymen were able to get to their flanks or rear. Bill used the hedgerows to his advantage, concealing his machine guns and flanking the Germans without the advancing riflemen masking his guns’ fire. The M1917A1s poured in fire to keep the defenders’ heads down until the riflemen wiped them out or the Germans capitulated. Slowly, the 12th Infantry cleaned out enemy stragglers in the target box, opening the way for more tanks and infantry. By nightfall, the battalion made its objective just outside the town of la Chappelle-en-Juger, which one soldier described as “nothing more than dust, scattered stones and roofing tiles.”23

Bill got little rest. The heavy machine gun platoon had a key role in defending a forward position against potential counterattacks, though that threat had diminished. The 2nd Battalion moved out mid-morning on July 27 toward an assembly area near le Mesnil-Amey. The 1st Battalion had already cleared the route the night before but the troops had to run to ground every German straggler. The battalion closed on its new position by noon. Once in position, the infantrymen began clearing the new area of the enemy in a series of small yet violent skirmishes. “It was an exhausting assignment, one that left us in a state of such debilitating fatigue that when we would slump to the ground for a break of ten or fifteen minutes we rarely spoke to one another.”24

Around 1645 hours, division warned the 12th Infantry about enemy tanks to the southwest and a possible German force attempting to withdraw south from Marigny. Colonel Luckett issued verbal orders to Major Johnson to join the 1st Battalion in clearing woods south of the St. Lo–Coutances highway. The 2nd Battalion would march south to the highway then west toward a major road junction. Major Johnson quickly rounded up the rifle companies and started the movement from le Mesnil-Amey by 1710 hours. General Barton attached a tank company and platoon of tank destroyers to the regiment to add weight to its attack. It took the 2nd Battalion several hours to get going because clogged roads delayed the arrival of the tanks and the troops had to march six kilometers just to reach the LD near the village of St. Benoit.25

The rifle unit and Bill’s platoon hurried forward against scattered small arms fire until someone noticed a sign saying, “Achtung Minen” posted in the field they were crossing. The infantrymen froze. Buried mines terrified soldiers. One unlucky step could cost a leg or a life. An alert soldier got them out of the jam when he spotted cows grazing nearby. The troops herded the cattle together and drove them across the field. The men followed the path the cows trampled. No mines detonated. Some German had posted the false sign to slow the American advance. They finally reached the St. Lo-Coutances highway at St. Benoit around 2100 hours.26

The battalion turned west along the highway and attacked. Without warning, a ground burst sent dirt, branches, and shrapnel flying past the heads of the infantrymen, followed a couple seconds later by a loud boom coming from the direction of Marigny. The men recognized the signature report of the dreaded German 88mm Flak gun. The riflemen scurried for cover and the tanks pulled back behind concealing hedgerows.

The Americans learned to respect the “88.” Originally developed as an anti-aircraft gun, it could hurl a twenty-two-pound projectile 39,000 feet into the air. In North Africa and Russia, the German Army realized that the high velocity of its projectile—2,690 feet per second—made it a formidable anti-tank weapon. The powerful 88 could shred a Sherman’s armor as easily as a .22 cal. bullet hitting a can of beer. One tanker in the 70th Tank Battalion paid reluctant homage to the 88. “It was the finest gun of the war. We had a peashooter 75[mm] with a low charge and were elevating at 200 yards while the Germans were shooting flat trajectory at about 1,000 yards.” In Normandy, the Germans employed the 88 in an indirect mode, like artillery, and direct fire role against Allied troops and tanks. One private reported a German gun crew using it as an over-sized sniper rifle.27

Upon the impact of the 88mm shell, Bill and his crews ducked for cover. While his machine guns could hardly hope to take on an 88 in a direct-fire shootout, they could put suppressive fire on the gun and its crew using indirect fire. Bill grounded his machine guns behind the concealment of a hedgerow and ordered the crews to establish an initial direction of fire against the enemy gun. A crewmember marked the azimuth by driving an aiming stake into the moist turf forward of the gun. While the crews mounted the machine guns on tripods, an observer tried to get a fix on the German gun. Another jarring explosion along the highway followed by a distant muzzle blast gave the observer the fix he needed. Using hand and arm signals, he gave Bill an estimate of 900 meters to the target. Referring to the firing table, Bill passed the Quadrant Elevation (QE) settings to the section sergeants who bellowed the fire command to the squads. “Prepare for fire order. Lay on base stakes. Boxes [ammunition] per gun: eight. QE: plus nine. Rapid.” The gunners elevated the guns by turning a handwheel on the cradle mount while the assistant gunners fed ammunition belts into the receiver. As soon as the gunners signaled they were ready, the sergeants barked, “Commence Fire.” The gunners unleashed a long initial burst.28

The observer, squinting through his binoculars, spotted the impact of the rounds and signaled adjustments, based on his line of sight (the O-T line). The sections had to correct the adjustments for the guns according to the G-T line. To reconcile the two target lines, they used the newly adopted M10 plotting board. These devices had a pivoting, transparent plastic disk mounted to a base with grid markings. The plastic disk’s pivot point represented the location of the guns. The section sergeants marked both the observer’s position and initial estimated target on the plastic disk with the help of the grid lines. Once the observer called back adjustments such as “Left 50, Add 100” the sergeants measured the angular correction to the O-T line and the new distance to the target from the OP. After marking the new target point on the disk, the sergeant rotated the disk to the G-T line and measured the corrections from the perspective of the guns. The crews then set new QE and traversing deflections on the gun mount.

The M10 plotting boards allowed the observers simply to report the adjustments from their vantage points. The crews could now correct the observer’s spottings for the G-T line, using the plotting boards, then set the guns’ QE and deflection. The crews and observers repeated the process until the observer saw tracer rounds kick up the dirt around the 88.29

The machine guns could harass and annoy the enemy gun but they could not take it out. Major Johnson called the regiment for help in dealing with the deadly 88, but the S-3, Maj. John W. Gorn, advised him to send out a couple of bazooka teams instead. The German 88 kept the Americans off the highway while daylight lasted.30

The German gun may have disrupted tank movement near the St. Lo–Coutances highway, but the American infantry could still maneuver through the brush as daylight waned. The infantry hopped over hedgerows and scurried across fields in the dimming light. They reached the north– south road running out of Marigny and sealed off that line of German retreat. From the south, a German strongpoint poured heavy fire into the battalion’s left flank. The rifle platoons, exercising aggressive fire and maneuver, rooted out the enemy as darkness closed in. The battalion then consolidated its position for the night. At midnight, it received orders from Division HQ to continue mopping up any resistance in their current zones on the morning of July 28.31

The troops awoke to eerie quiet the next morning. The rifle platoons searched the area south of Marigny but found no Germans. Whatever enemy elements had lingered in the zone of action the day before had slipped away under the concealment of night. The battalion cleared the road coming from Marigny of mines by 1000 hours, allowing the American tanks to rumble south. Troops discovered forty hastily dug German graves west of the highway and a cache of abandoned weapons and ammunition where the German 88 had been the previous day. The evidence left no doubt that the Germans had fled. The tired infantrymen came to a startling realization—they had broken through the Normandy front. The cohesive German defensive line had been torn open like a canvas sail in a hurricane. The frustrating slog through the bocage was behind them. The VII Corps could now drive into the depths of the German rear. The war on the Western Front had entered a new phase.32