Field Marshal Montgomery’s 21st Army Group represented the Allied main effort in February and, consequently, absorbed the most resources. In Operations Veritable and Grenade, Montgomery’s three armies—the Canadian 1st, British 2nd, and American 9th (which came under Montgomery’s command during the Ardennes Campaign)—advanced toward the west bank of the lower Rhine River, a prerequisite for any assault into Germany. General Bradley, commander of the 12th Army Group, did not want his forces to stand idle, merely guarding Montgomery’s southern flank. He drafted a plan called Operation Lumberjack that would clear the west bank of the Rhine between Cologne and Coblenz. Bradley planned to drive the First Army to the Rhine then turn it southeast along the west bank to meet Third Army’s thrust through the Eifel. Bradley intended to crush the German forces remaining west of the Rhine between Hodges and Patton. General Eisenhower approved the plan but told Bradley to wait until Operation Grenade had progressed to the point that Hodges’s First Army would no longer be required to secure Montgomery’s flank. By late February, the U.S. Ninth Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. William H. Simpson, had punched through to the Rhine and the success of Grenade looked assured. Bradley issued orders to execute Lumberjack with a projected starting date of March 3.1

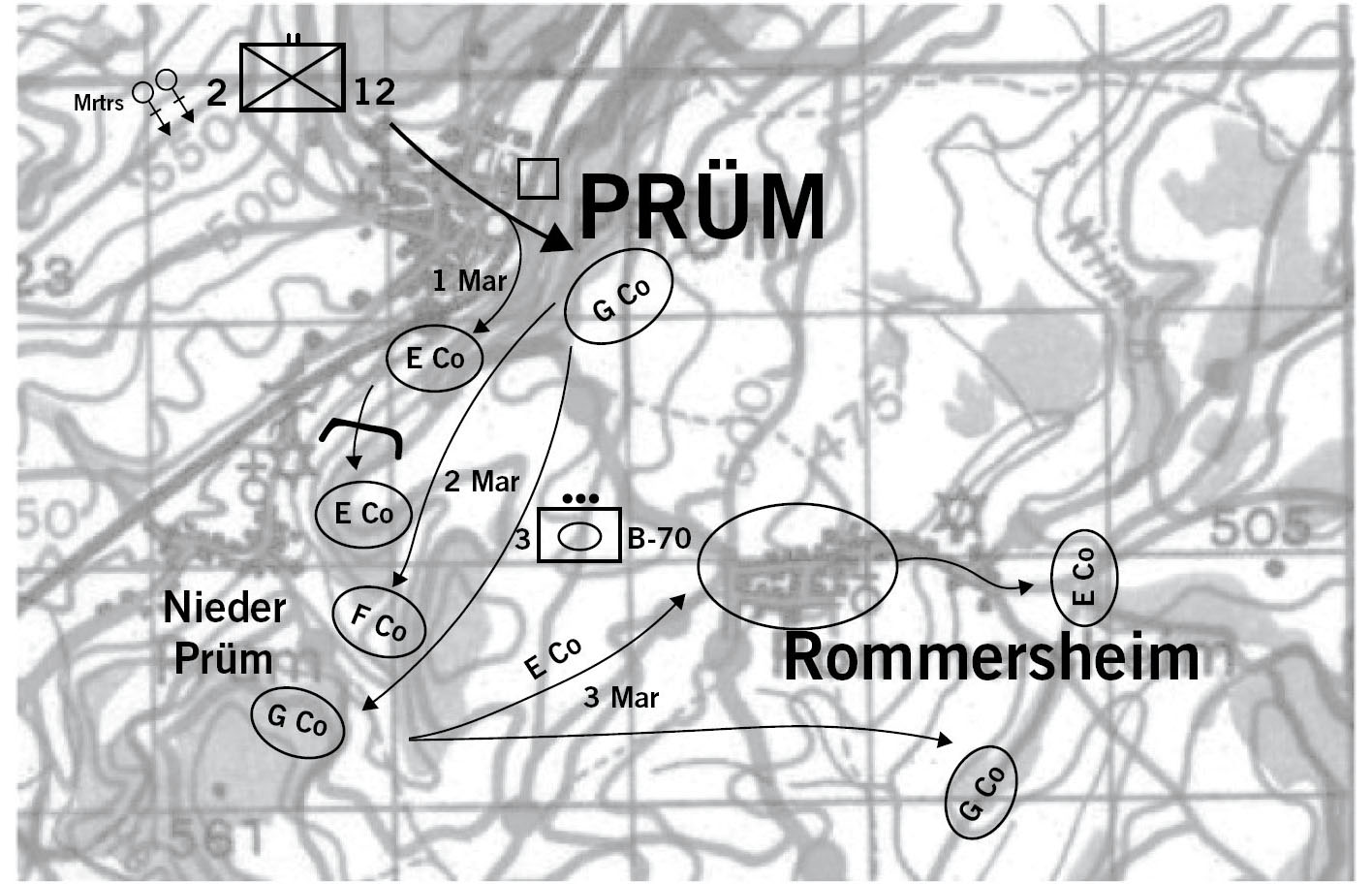

The 4th Infantry Division started a preliminary offensive on February 28 with CTs 8 and 22 leading the way. The division had to establish a bridgehead over the Prum River wide enough to allow the 11th Armored Division to pass through and roll to the Rhine. The German 5th Parachute Division—many of its members newly recruited Hitler Youth who had never strapped on a parachute—faced the Ivy Division. The 12th Infantry stayed in reserve until the division secured the high ground on the east side of the river opposite the city of Prum. CT 12 got into the action on March 1. Colonel Chance ordered the 1st Battalion to pass through Prum, then take over a defensive position on the far bluff from the 22nd Infantry. The 2nd Battalion would follow the 1st Battalion through Prum then attack south, along the high ground, to seize Nieder Prum.2

Colonel Gorn’s battalion started the day at 0800 hours in Brandscheid. The men marched eight kilometers along muddy roads toward Prum while their sister battalion cleared the city while under fire from rockets and an AT gun. By noon the 1st Battalion finished mopping up isolated enemy outposts inside the city and threw a footbridge across the river. The 2nd Battalion’s rifle companies moved into Prum and waited for the 1st Battalion to complete its crossing.3

The men found temporary shelter in the piled rubble that was once a medieval town. Prum first came within range of American artillery back in September during the battle on the Schnee Eifel. From then until December the Americans periodically bombed and shelled the town to interdict the movement of German vehicles and supplies. The 22nd Infantry Regiment entered the city on February 12 after a heavy artillery preparation. The Germans, holding the high ground on the east side of the Prum River, had shelled the city ever since. The sustained pounding by both sides had demolished the place. Debris covered everything: homes, stores, yards, and avenues. Bill couldn’t find two bricks lying atop each other in some sections of Prum. Parts of it had been flattened, desolation exceeding anything he had seen before.

At 1515 hours, E Company dashed across the narrow footbridge, followed by G Company. Bill positioned the 81mm mortars in defilade behind the Kalvarien Berg, the ridge overlooking Prum from the west. From this protected location, the mortars could strike targets along the bluffs east of the river on a 90 degree arc from Prum to Nieder Prum. The platoon’s observers could view the battalion’s entire zone of action from the top of the berg and still communicate directly with the gun crews. They also had the rare luxury of being able to set up the aiming circle and range finder to spot rounds and adjust fire during an attack.4 (See Map XII)

E Company’s rifle platoons began moving south along the face of the bluff under the concealment of a fir and beech woodland. The company advanced slowly as the riflemen tottered on the steep slope, slipping on the wet, leafy ground. The platoons emerged from the concealing woods and continued heading southwest on a grassy part of the bluff. Seven hundred meters past the footbridge the face of the bluff swelled slightly, just enough to mask the southern length of the slope. The minute E Company crossed this feature, streams of small arms fire from a patch of woods two hundred meters away ripped through its ranks, forcing the riflemen to the ground. The slight swell in the face of the bluff blocked the supporting fires from G and F Companies. E Company’s infantrymen could only engage the defenders by moving past the swell into open ground. As the enemy paratroopers raked the slope, a self-propelled AT gun began shooting from a water mill near Nieder Prum.

Bill’s mortars lit up the woods above Nieder Prum as soon as the call for fire came in, dropping rounds “as rapidly as accuracy in laying the mortar permit[ted].” The bombardment and suppressive fire from H Company’s heavy machine guns made the enemy flinch but, protected by overhead cover, they still had the upper hand.5

E Company attempted to maneuver against the dug-in Germans but the enemy small arms fire proved too intense. The E Company Commander broke contact with the Germans then called back to battalion, telling Colonel Gorn that his company was stuck. With daylight waning, Gorn told E Company to stay put. That night, he and his staff put together a plan to seize Nieder Prum and bail out their forward company.6

Bill got called into Prum that evening for a meeting of H Company’s officers. The ruined city made a depressing backdrop for the conference but a small gesture by one of Bill’s friends helped boost spirits. Before the meeting started, the company mess team treated the officers to a meal. When Bill entered the makeshift officers’ mess, he did a double take. He found a table arranged with complete place settings of china and crystal.

“Where did you get the china and crystal?” he asked.

One of the mess sergeants answered, “Lieutenant McElroy found it.”

“Where?”

“In Prum.”

“How the hell did he find anything left in Prum? The city’s been completely destroyed.”

“Don’t know but he dug it up somewhere.”

First Lt. David J. McElroy had already earned renown as a scrounger and someone who could get things done. This time he had outdone himself. Bill would’ve been astonished to have found an unbroken plate in the wreckage around Prum. To have found a complete china and crystal service seemed impossible.

A couple of weeks later the division HQ put out a request for a new aide-de-camp for the commanding general. Maj. Gen. Harold Blakeley wanted to select a combat officer from the division’s ranks, and he asked the battalions to nominate a suitable lieutenant.

Bill knew the perfect man—Dave McElroy. “Tell division they can call off the search. I have the name of the guy they want.” General Blakeley personally interviewed the candidates for the aide’s position but as soon as he met with McElroy the interviews stopped. McElroy served as the general’s aide-de-camp for the remainder of the war.

Colonel Gorn resumed the attack at 0500 hours on March 2 with E and G Companies moving abreast toward Nieder Prum. G Company moved along the top of the bluff while E Company stayed on the slope. Low clouds hung in the valley. Poor visibility forced Bill and the mortar observers to move with the rifle platoons and call back to the guns via radios or telephones. The 81mm crews had registered on the German positions the day before but the changes in weather affected the trajectory of the rounds. The observers had to get close enough to spot the impact of the rounds before the mortars could adjust fire onto their targets.7

Once again, E Company marched into severe small arms fire at the swell in the slope. The rifle platoons maneuvered forward but the company commander lost contact with two of them. E Company tried to regroup but the platoons discovered that a minefield separated them. By 0635 hours, the company commander still had not regained control of his platoons, and the attack stalled. Gorn committed F Company to relieve E and push the German paratroopers off the end of the bluff. G Company had more success on its advance over the high ground. By 0700 hours, it had crossed a ravine and driven to a second bluff due east of Nieder Prum. It took until 1000 hours before F Company tied in with E Company on the first bluff. The two companies finally drove the German paratroopers from the woods. By 1115 hours, they could look down into Nieder Prum from the ridge northeast of town.8

The battalion still had the mission “to capture Nieder Prum and the high ground south and east.” The rifle companies already occupied the dominant ridges overlooking the town, so Colonel Gorn ordered F Company to push into Nieder Prum from the northeast while G Company attacked to seize the high ground south of the town. Gorn held E Company on the high ground to reorganize and, if need be, defend the battalion’s rear.9

The afternoon attack did not proceed smoothly. F Company found its way into Nieder Prum littered with mines and booby traps. With so many obstacles, Gorn decided the town had no value for future operations. He got approval from Colonel Chance to leave the town for follow-on forces and concentrate on taking the high ground to the south. G Company attacked across a ravine to Hill 561 in the late afternoon. An enemy machine gun fired on them, but the men pressed forward and reached their objective by 1840 hours.

Assessing the day’s actions, Colonel Gorn concluded that E Company’s attack had lacked aggressiveness and tactical control. He put it down to its commander’s lack of combat experience. Although a senior first lieutenant, the commander had only recently arrived in theater. Gorn decided that E Company needed a change of leadership to boost its fighting spirit.

Bill received a message to meet with Colonel Gorn in the battalion CP. Unsure of the purpose of the meeting, he reported to Gorn. The colonel explained the situation in E Company then asked Bill, “Do you think you can handle commanding a rifle company?”

“Hell, yes!” Bill answered.10

Gorn smiled. It was just the type of response he was looking for. “Okay, the job is yours.”

Bill was not an obvious choice for the position. He had only been commissioned for twenty months and all that service had been in a heavy weapons company. Gorn chose to overlook this, and Bill’s reputation for brashness, because of his solid performance as a weapons platoon leader and extensive experience fighting alongside rifle platoons.

The new assignment pleased Bill. Before, he thought the only way he could ever leave H Company was to transfer to the engineers or get killed. Company command meant future advancement in rank, more pay, and better career prospects. He now led 193 men, further confirmation that he had measured up. There was one major hitch. Because Bill had less “time in grade” and “time in service” than the minimum required for promotion, he stayed a first lieutenant. He had to hold a captain’s slot for three consecutive months before the Army would bump him in rank. Bill had seen plenty of lieutenants take over companies only to be carried out on a stretcher or replaced by a newly arrived captain. Few made it to captain.11

Bill remained at the Battalion CP to attend the briefing for the next day’s operation. The battalion was turning east to drive the Germans away from the Prum River and provide maneuver space for the 11th Armored Division to unleash its tanks. The colonel wasted no time testing his newly assigned company commander. “E and G Companies will seize the town of Rommersheim and the ridge one kilometer east of the town.” G Company would lead the movement by sweeping south of town. E Company would initially follow G then turn northeast to seize Rommersheim. After that, the two companies would advance east to higher ground.12

After the briefing, Bill worked his way, in the dark, over the brushy slopes to E Company. He immediately called in the platoon leaders. As soon as they assembled at the company CP, Bill announced that he had taken command and immediately issued his operations order for the next day’s attack. He began by reviewing the enemy situation and the battalion’s overall plan. The mission for E Company, he told them, was to seize Rommersheim then the high ground beyond it. He explained the details for the company’s plan of attack. The new commander went over the “scheme of maneuver” and the “plan for fire support.” He designated the roles each platoon would play in the attack. He told the company’s key leaders how supplies were to be distributed and the wounded evacuated. Bill closed the order by passing out the radio frequencies, call signs, and the new chain of command.

The order followed the classic format of the Army’s five-paragraph field order, just as Bill had learned it at Fort Benning. Its detail and thoroughness also mirrored his principles for doing things the proper way and sticking with tactical doctrine. After he dismissed the platoon leaders, one of the experienced officers, 1st Lt. Patrick Tuohy, approached him. “You know, sir, that’s the first time I’ve heard a five-paragraph field order since I arrived in Europe.” Bill nodded. Tuohy’s statement was tacit affirmation of the new standard for E Company. The two officers formed a professional bond in that moment.

Rommersheim lay east of two small, barren hills that protected the little town from the ridges overlooking Prum and Nieder Prum. Rather than defend the exposed hilltops, the Germans defended the eastern or reverse slope. A “reverse slope” defense is a tactic that sets up positions on the back side of a ridge or hill rather than its crest. The defender sacrifices observation and wide fields of fire but gains other advantages. The attacker must cross over the hill and expose his leading elements before he can engage the defender, thereby losing the ability to mass supporting fires from the units trailing the lead elements. A careless attacker, still in column formation, who stumbles into a “reverse slope” defense runs the risk of feeding his subordinate units into the defender’s kill zone, one at a time. Colonel Gorn’s plan avoided this trap by swinging around the hill instead of marching down the road from Prum or straight east from Nieder Prum.

G Company started movement at 0900 hours on March 3. E Company shifted south, behind them, before crossing the LD. The two infantry companies advanced slowly up and over the high ground south of Rommersheim. G Company continued straight east through a draw south of town. Bill reoriented E Company to the northeast. By early afternoon, the company advanced toward Rommersheim, guiding along a road that entered the town on its southwest corner. Bill used a slope of the southern hill to mask his approach and provide cover for the rifle platoons to within three hundred meters of town. He also deployed the platoons on line to present maximum firepower forward. The platoons opened suppressive fire then, using fire and maneuver, individual rifle squads attacked. The Germans stood their ground and a sharp firefight brewed up. Bill called on H Company’s heavy machine guns and mortars for support, and the latter began hitting the enemy with the heavier M45 rounds. A platoon of tanks from B Company, 70th Tank Battalion popped over the hilltops and fired into Rommersheim, adding even more firepower to the assault. With tanks firing from one direction and infantry assaulting from another, the Germans gave up and pulled out of Rommersheim. E Company seized the town by 1630 hours, rounding up fifteen prisoners and counting ten dead Germans.13

While the enemy had not defended Rommersheim in strength, the successful and well-organized attack served as a tonic to the men of E Company after the frustration of the previous two days. Keeping his feelings to himself, their new commander quietly rejoiced that he had taken his first objective.

E Company did not have time to celebrate—the mission continued. The rifle platoons took an hour to clear the buildings in town before they proceeded east. Elements of the 14th Parachute Regiment had withdrawn to defend the high ground on the far side of Nims Branch, a creek that ran north-to-south just east of Rommersheim. G Company had already run into heavy small-arms fire a kilometer south of E Company. Bill’s rifle platoons crossed Nims Branch and started moving uphill to their final objective. By 1835 hours, E Company hit the German defenses. The attack pushed the paratroopers back five hundred meters, to a point where several roads intersected. With darkness falling, there was not enough time to coordinate a more deliberate attack up to the top of the hill. Both E and G Companies dug in on the southern extension of the high ground.14

While 2nd Battalion was busy at Rommersheim, CCB of the 11th Armored Division passed through the 4th Infantry Division and assembled on the open ground north of Rommersheim. From that spot VIII Corps launched it into the Rhineland. CT 12 would spend the next few days trailing the armor and mopping up bypassed defenders.15

The crossing of the Prum River, the capture of Rommersheim, and the presence of the 11th Armored Division forced the Germans to abandon their defense of the rolling farmland east of Prum. They fell back to the next defensible terrain, the Kyll River, leaving behind scattered delaying forces. CT 12’s mission became clear—advance rapidly behind the armor all the way to the Kyll River.16

The 2nd Battalion led with two combat patrols at 0200 hours on March 4. Its scouts secured a position five hundred yards to E Company’s front. G Company moved out early and, by dawn, had advanced several hundred meters. E Company moved forward at 0645 hours, reaching the scout position by 0830. Bill then sent a patrol to reconnoiter the route another six hundred meters ahead.17

By 1000 hours, the lack of contact with the Germans convinced Colonel Chance that the enemy had withdrawn. He told Colonel Gorn to keep E Company advancing on foot and send F Company into Fleringen to relieve part of the 1st Battalion. Chance turned his sight to the next objective. At 1125 hours, he ordered G Company to mount on the attached tanks and tank destroyers for a rapid dash to Wallersheim. Word came down from division that CCB had already bounded forward to Budesheim. At 1230 hours, Chance called Colonel Gorn to urge him forward. “Have F Co. move right thru Fleringen…Get the whole Bn moving. Keep in contact with the armor.”

Bill pushed E Company forward in the direction of Wallersheim. The sustained movement, known as an “approach march,” gave Bill an opportunity to control the tactical movement of his rifle platoons. By doctrine, rifle companies had to move forward in dispersed formations that provided protection from enemy artillery and small arms fire yet still allowed the company commander to control his platoons. These competing goals required the men to spread out for protection but remain grouped for easier communication. Much depended on the terrain. “Consequently, platoons will be separated laterally, or in depth, or both. On open terrain, platoons may be separated by as much as 300 yards. In woods, distances and intervals must be decreased until adjacent units are visible, or, if the woods are dense, connecting files or groups must be used between platoons.” Bill gained some needed experience controlling E Company as it repeatedly drew in then extended as it encountered woods, farmland, ravines, and hills.18

G Company, riding the attached tanks and tank destroyers, breezed into Wallersheim at 1435 hours. E and F Companies tramped into town a short time later. Colonel Chance gave them little time to rest. He wanted to gain more ground. At 1600 hours, he issued orders to continue the advance. E and F Companies marched another two kilometers to occupy Hill 631, wooded high ground due east of Wallersheim. Colonel Chance, still not quite satisfied, directed 2nd Battalion to send a patrol forward to block a road 1,800 meters beyond E Company. G Company obliged, dispatching a platoon to establish the outpost after dark.19

After securing his own defensive position on Hill 631, Bill bedded down his tired troops in the woods. The men had advanced seven kilometers. Although they had almost no enemy contact, the company had marched steadily in tactical formation the whole day.

The 2nd Battalion enjoyed a quiet day on March 5. Most of the action occurred north of their sector. Before CCB could charge to the Kyll River it had to pass through the town of Oos and cross a bridge over the Oos River, a minor tributary of the Kyll. C Company set out early on March 5 to seize the crossing for the armor. Just as it approached the town, the Germans blew the bridge, and paratroopers, fighting from hills on the far side of the river, put small arms fire on Oos. The 1st Battalion joined the 2nd Battalion of the 22nd Infantry in a vicious battle against the German paratroopers that lasted into the night. It ended with the enemy getting wiped out. Meanwhile, CT 12 ordered Gorn’s Battalion to consolidate in Budesheim as the regiment’s reserve.20

The 1st Battalion cleared the way, and the engineers bridged the Oos River overnight. CCB jumped the river at 0700 hours on March 6. The tankers drove north past marshy ground then swung east. They passed over high ground northeast of Roth and surged to the Kyll River valley. By 1020 hours CCB reached the town of Niederbettingen. The armored force had covered seven kilometers before lunchtime.21

The 2nd Battalion started the day in Budesheim as the regimental reserve. The rapid armored advance prompted Colonel Chance to order them forward to Oos at 0940 hours. When the men arrived at 1220 hours, they were greeted by an incoming artillery barrage that sent Bill and his men ducking for cover.

General Blakeley and Colonel Chance wanted to keep the infantry as close behind the 11th Armored Division as possible. All three battalions of CT 12 pressed forward with 2nd Battalion advancing to Roth.

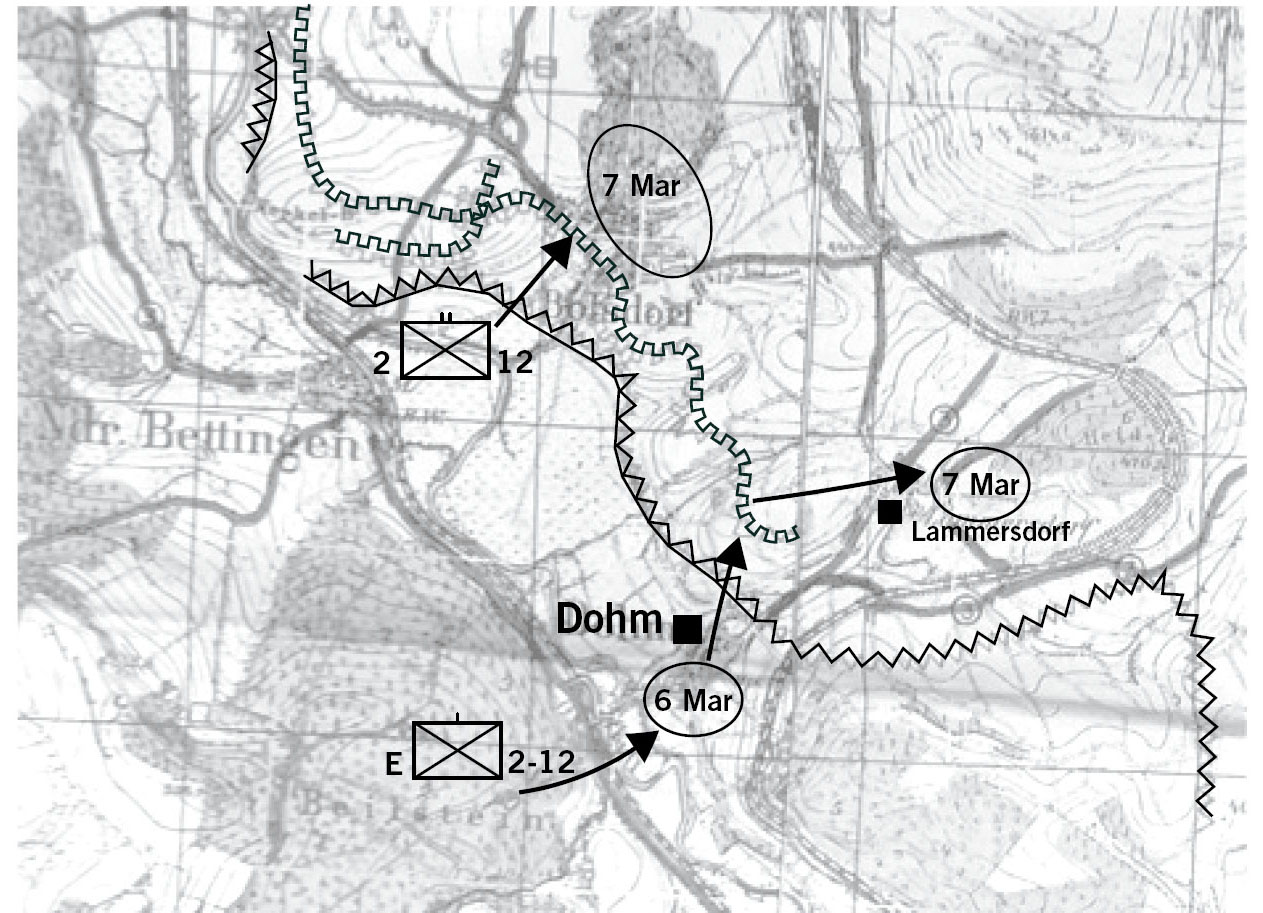

The 11th Armored stopped at the Kyll. It had to establish crossing sites and a bridgehead before its tanks and halftracks could get over the river. On the east side of the river, a tank ditch, backed by infantry trenches, sprawled between Bolsdorf and Dohm. The 55th Armored Infantry Battalion of CCB forced crossings at Oberbettingen and Niederbettingen. Bad road conditions delayed the arrival of bridging equipment, so the engineers improvised. They created a ford by dropping a bridge span into shallow water. However, the tankers did not consider the crossing suitable.22

Farther downstream, the armored infantry forded the river at Dohm. CCB wanted to drive east but it ran into the extensive tank ditch that cut the road between Dohm and Lammersdorf, also covered by infantry in nearby trenches. Until they could drive off the German infantry, CCB was stuck in Dohm.

The 4th Infantry Division needed to break the German obstacle belt to get the rest of the 11th Armored over the Kyll River. CT 12 ordered Colonel Gorn to assist CCB in Niederbettingen. General Blakeley called Colonel Chance forty minutes later to work out more details for the river crossing. They decided to have two companies of the battalion assault across the river from Niederbettingen to Bolsdorf. They tasked E Company to relieve the armored infantry at the Dohm fording site.23

Bill kept his men moving well into the evening. They reached the fording site near midnight. Squad by squad, the infantrymen slid off the bank into the frigid river. The men teetered under their loads, stepping rock to rock, guided by the light from a waning moon. They made it safely across but emerged soaked and chilled. (See Map XIII)

E Company took over from two companies of the 55th Armored Infantry and settled into Dohm for the night. With no chance to change or dry their clothes, Bill and his men fought against the wet and cold the rest of the night. Upstream, F and G Companies waded the river under equally harsh conditions.

E Company’s mission for March 7 presented Bill with his biggest challenge since taking command. While the rest of the battalion would attack Bolsdorf, his company had to dislodge an entrenched German force on its own. Bill could call on an 81mm mortar section and a platoon of heavy machine guns from H Company but, to assault the objective, he only had his own weapons platoon and three rifle platoons to “close with the enemy by a combination of fire and movement.” His first task, according to doctrine, was reconnaissance. Aided by a detailed map over-printed with the German fortifications, Bill scouted the enemy position “to determine where enemy guns and men…might be located [and] the routes or areas where the enemy’s observation or fire [was] most hampered by the nature of the terrain.”24

Bill followed tactical doctrine by drafting a “scheme of maneuver” that took “advantage of every accident of the terrain to conceal and protect the company…while in movement.” As usual, the Germans had cleverly positioned their defenses. From a farm on a gently rising hill northeast of Dohm, German gunners had observation over the tank ditch and the approaches all the way down to the river. The defense did have one significant weakness. The hill naturally bowed out toward the river. That meant the gunners defending the north side of the position could not fire to the south and vice versa. The Germans compensated by digging trenches that allowed them to shift men from one sector to the other. Bill also noticed that the buildings in the little town of Dohm would offer some cover for his infantry as it approached the southern side of the trenches.

Bill’s experience in H Company paid dividends as he prepared his plan of fire support. He could use the 81mm mortar section and E Company’s own section of three 60mm mortars to drop rounds inside the trenches at certain points and prevent the enemy from shifting troops into a threatened sector. The Germans dug their trenches in a zig-zag pattern. By using high-angle indirect fire, the heavy machine guns could target sections of the trench that aligned with the long axis of their plunging fire. Where the heavier weapons were not firing, Bill’s own M1919 machine guns and the platoons’ rifle fire would force the enemy to keep their heads down.

Bill briefed his key leaders on his plan of attack in the early hours of March 7. “The men and my platoon leaders were dubious about jumping due to the Jerry[’s]…tactics and his superior positions.” The other lieutenants wanted to hold off making the attack until the rest of the battalion could help. Bill later confided to Beth his anxiety. “At that time I had a tough decision. I was new to the company and the company plan was my own. If it failed the men would lose a lot of confidence in me and it was a tough job.” After listening to his subordinates’ objections, Bill elected “to override my 5 officers and jump as planned.”25

The 2nd Battalion began the operation with F and G Companies attacking to seize Bolsdorf and a knoll just north of that town. The Germans resisted fiercely from the buildings. Both companies spent the morning trying to dislodge German paratroopers, taking thirty casualties. The heavy fighting in Bolsdorf meant that E Company would have no help. The junior lieutenants again objected to the attack but Bill held firm.26

At Bill’s signal, the supporting machine guns and mortars opened fire. Before any infantry could advance, the enemy gunners had to be pinned inside their positions. Bill motioned for the lead platoon to advance once the volume of suppressive fire on the trenches reached its peak.27

Infantry companies did not charge German defensive positions in a single rush. Instead, they bounded their rifle platoons forward one at a time. The majority of riflemen had to remain busy firing at the enemy in order for a handful to rush forward—the greater the enemy fire, the fewer men moving. As Army doctrine put it, “This combination of fire and movement enables attacking rifle elements to reach positions from which they can overcome the enemy in hand-to-hand combat.”28

The riflemen clawed their way up the gentle incline in a series of short, quick dashes. Bill stayed forward with the rifle platoons where he could best control the attack. When they closed on the trenches, he signaled the supporting mortars and machine guns to lift fire for the final assault. As soon as they did, the American infantrymen leaped into the trenches and killed those who did not immediately surrender.

E Company still had more terrain to seize. Besides the trenches, one hundred enemy soldiers in Lammersdorf blocked the road leading east from Dohm. Bill and his men had to drive them out before the bridgehead could be secured. This time, E Company had some help. The 3rd Battalion had forded the Kyll at Dohm and seized the high ground south of town. From that position, 3rd Battalion could bring some of its heavy weapons to bear on Lammersdorf. Bill conferred with the sister battalion around 1515 hours to secure their help.29

Bill’s plan of attack exploited the capture of the trenches. The town sat in low ground. The Germans could block the road but with E Company occupying the trenches above Dohm, they did not have a secure defense. Bill planned to maneuver into terrain that could dominate the little town. He also coordinated with the artillery to pound Lammersdorf in advance of the assault.

The attack began in the late afternoon. With artillery blasting the town and small arms fire pouring in from multiple directions, the Germans abandoned Lammersdorf. The 3rd Battalion reported enemy troops dashing out of one side of Lammersdorf as E Company entered from the opposite end. The company finished the day by occupying the wooded hill just beyond the town.30

The action of March 7 gave E Company a big boost in morale. It had overrun an enemy trench line, driven the Germans from Lammersdorf, and captured sixteen enemy soldiers while suffering only two casualties. The regiment applauded the company’s performance, calling it “a brilliant attack.” Bill wrote to Beth, “Thank goodness we made it so now the men feel very tough and capable.” Back at the battalion CP in Niederbettingen, someone else felt justified by E Company’s success. Colonel Gorn noted that the young lieutenant he picked to command the company had restored its fighting spirit in less than a week.31

Late in the day, Colonel Chance ordered 1st Battalion to pass through the 2nd Battalion and carry the attack farther east. The 2nd reverted to regimental reserve.32

On March 8, the division formed Task Force (TF) Rhino by putting the 8th Infantry on trucks and combining elements of the 70th Tank, 610th Tank Destroyer, 4th Engineers, and 29th Field Artillery Battalions with the 4th Recon Troop. Under the command of the Assistant Division Commander, Brig. Gen. James Rodwell, TF Rhino roared across the Rhineland, advancing twenty-five miles and capturing 1,541 prisoners in twenty hours. Even at that breakneck pace they could not keep up with the collapsing German defense. By the time TF Rhino completed its run, on March 9, the 4th Armored Division closed on Koblenz and the Rhine River. Two days earlier, the 9th Armored Division captured a bridge over the strategic river at Remagen. Operation Lumberjack culminated with the Germans evicted from the Rhineland and the Americans holding a bridgehead over the Rhine.

The 12th Infantry remained in place for a few days, giving the troops a chance to clean up and rest. The only contact they had with the enemy came on March 11 when a lone German soldier drifted into Lammersdorf to surrender. He explained that he had wandered the countryside for a week but none of the German civilians would feed or shelter him. He finally gave up and turned himself in.33

Things got even better on March 12. The battalion’s troops rode trucks from Niederbettingen to Bleialf where they hopped on rail cars for a long move to a rest area around Portieux la Verrerie, France. The new area, near the Moselle River in the region of Lorraine, offered billets for all the soldiers as well as showers, clean clothes, and hot chow. Bill shared the news with Beth. “We are in a rest area now! Can you believe it, the 4th Div. in a rest area!!...It is the first time I have not heard the roar of a cannon since 7 Jan.” The men were not entirely idle. Colonel Chance insisted on a training program to ensure all soldiers knew how to operate key weapons and their rifles. The battalion started rotating officers on a schedule of three-day passes to Paris. Bill drew his pass on March 16.34

Bill enjoyed his short holiday in the French capital but he noticed that the euphoria of August had gone. The warmth and affection for American soldiers had been cooled by a slight chill of resentment. He noticed some Parisian merchants skinning a few extra dollars off ignorant GIs.

Bill also saw that the debris of war remained weeks after the campaign had passed. The French appeared to accept the disorder left by the fighting. He had seen something different in Germany. German civilians worked quickly and diligently to repair the damage left by the combatants the moment the frontline swept beyond their homes.

The Germans earned Bill’s grudging admiration for their industry, just as they had for their fighting ability. Despite his personal suffering at their hands, Bill never made deprecating comments about the Germans. He certainly condemned the Nazis and abhorred Germany’s war atrocities, but that did not seem to diminish his overall opinion of the German people. These feelings contrasted with his attitude toward his allies. Bill inherited his mother’s Irish animosity against the English. His time in England and Field Marshal Montgomery’s fighting record failed to improve his view of them. As for the French, their warmth and joy seemed to slip into disdain and arrogance after the glow of liberation faded.

Shortly after Bill returned from Paris, the 2nd Battalion moved to the hamlet of Kriegsheim, outside Hagenau, France. In this assembly area, the men had to wear helmets and shoulder their weapons. The familiar tank, tank destroyer, and artillery battalions rejoined them in the assembly area. The regiment transformed back to CT 12. The men still enjoyed movies, recreation, and showers, but they knew their down time would not last much longer.35

CT 12 moved into the plains of the upper Rhine Valley on March 26. As the troops trucked across the German border, they saw numerous displays of white bed sheets hanging from windows, what they termed “the new German national flag.” The regiment occupied an assembly area around Ellerstadt, a few kilometers east of Bad Durkheim. With an impending offensive deep into German territory, the battalion issued a general policy governing interactions between the troops and the German civilian population. The S-2 cautioned the men about “the order prohibiting fraternization between soldiers and civilians.” The men also learned that the 4th Infantry Division had been transferred to XXI Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Frank Milburn. The XXI Corps served in Lt. Gen. Alexander Patch’s 7th Army under Gen. Jacob Devers’s 6th Army Group. If any of the men wondered why they had been moved from Bradley’s command down to the southern army group, the reason became clear when they heard that the 7th Army had forced a crossing over the Rhine River at Worms. Four days later, CT 12 was ordered to cross the Rhine at Worms to re-enter the fight.36

The upcoming campaign into the heart of Germany would present Bill with severe challenges of both a military and moral nature as the American Army brought the ravages of war to the doorsteps of the German people.