In the fall of 1944, a handful of news correspondents in Europe began speculating on desperate measures the Third Reich might take to prolong its survival. One idea the writers floated was the creation of an Alpenfestung, literally “Alpine Fortress,” where well-armed and well-supplied Nazi fanatics could hold out indefinitely within an inter-connected ring of mountaintop bunkers. This speculation received scant attention from Allied intelligence until the Battle of the Bulge. Hitler’s bold gamble in the Ardennes set the G-2s to wondering what else he might do to delay the inevitable. Allied planners considered the construction of a “National Redoubt” in the Alpine region the most worrisome option. Once they latched onto that dubious theory, intelligence staffs had no trouble finding facts and random bits of evidence to support it. By the beginning of January 1945, Propaganda Minister Goebbels got into the act by falsely promoting Allied fascination with the National Redoubt.1

As early as January 1945, the concern about an Alpenfestung began to influence Allied strategy. Eisenhower wanted to finish the war in Europe as quickly as possible so America could shift resources to the war in the Pacific. A stubborn defense of some sort of Alpine fortress could delay final victory for months, even years.

The collapse of German resistance west of the Rhine, the capture of the bridge at Remagen, and the advance of the Red Army into eastern Germany caused a simultaneous shift in Allied thinking. Berlin diminished as an objective in Eisenhower’s calculations. After the capture of the Ruhr, preventing a Nazi withdrawal into the National Redoubt became the next most important strategic goal.

Eisenhower announced his plans for the final push into the German hinterlands on March 28. After crossing the Rhine, Montgomery’s 21st Army Group would drive northeast to cut off Denmark from Red Army encroachment. The U.S. First Army and Ninth Army, now back under Bradley’s command, would encircle and reduce the Ruhr. Patton’s Third Army would guard First Army’s flank until the Ruhr fell, then charge east-southeast toward Leipzig. Patch’s Seventh Army, under Devers’s 6th Army Group, would exploit its Rhine bridgehead to the east then hook sharply south to turn the German First and Nineteenth Armies that defended the upper Rhine Valley. Patch would continue driving south across the Danube River to overrun the National Redoubt before the German Army could occupy it in strength.2

General Milburn’s XXI Corps surged east from the Worms bridge-head with the 12th Armored Division in the lead. The tankers forced their way through the Odenwald, the forested highlands east of the Rhine. Milburn ordered the 4th Infantry Division to follow. On March 30, CT 12 crossed the Rhine at Worms.3

The regiment had problems getting underway. Their own vehicles and attached motorized units drove across the bridge as scheduled and occupied an assembly area southeast of Heppenheim. However, the trucks to haul the foot soldiers did not arrive on time. The deuce-and-a-halves showed up the next day then had to play catch up, chugging their way through multiple traffic jams. The convoy made a tempting target for an aerial attack but the Air Corps provided ample cover, much to the relief of Bill and his men. “Thank God we have an Air Force!”4

While passing through Worms, the men got their first glimpse of a sight that would become both disturbing and common. A long column of “displaced persons” (DPs) walked and bicycled in the opposite direction, heading home after years of enslaved service to the Reich. In August 1944, 7.6 million foreign laborers, most of them conscripted, constituted 25 percent of Germany’s work force. With the Allies and Red Army breaking into the Fatherland, these people began spilling out of Germany in droves.5

The truck convoy finally caught up with the rest of CT 12, and the entire combat team gathered in an assembly area on the night of March 31. The 2nd Battalion centered around the hamlet of Airlenbach. The regiment picked up sixteen German prisoners during the movement who had either deserted or surrendered while home on leave.6

CT 12 remained in division reserve on April 1 and made another road march to Hardheim, using the invaluable trucks to shuttle the march serials forward—and collecting another fifty-four PWs. The 2nd Battalion assembled that evening near Erfeld, a small village south of Hardheim. The day had been quiet until a German jet dropped a single bomb in the battalion area. The bomb caused no damage, but the attack reminded the Americans that the war was not over yet.7

The regiment stayed put on April 2 while the rest of the Ivy Division pushed east to the Tauber River. Bill and his men spent most of their time cleaning weapons and equipment. The only serious event occurred near evening. A dozen ME 109s swooped in to strafe Erfeld and drop a bomb. The battalion suffered no losses but the aerial attacks proved how sensitive the Germans had become to the XXI Corps thrust. A little before noon the next day, the regiment issued new movement orders. The 2nd Battalion moved to Herchsheim, another thirty-four kilometers to the east. The movement put them close to Ochsenfurt on the Main River. This time, the troops dug in a defensive perimeter.8

By now, the 12th Infantry had gone nearly a month without serious contact with the enemy. It had used the time wisely. The rest period in France had rejuvenated the spirits of the veterans and given the new recruits time to fit in. Everyone got refresher training on weapons and tactics. Unlike the brutal days in Normandy, the squad leaders acquainted the replacements with the dangers of combat and showed them how to fight the Germans. Two of Bill’s officer friends, Jack Gunning and Ben Compton, left for new assignments. First Lt. Frank Hackett replaced Compton in command of H Company. Bill’s battalion stood primed for action and ready to unleash a swift campaign to finish off what appeared to be an already defeated enemy.

The eastward surge of General Patch’s Seventh Army had driven a wedge between the German First and Seventh Armies. The XIII SS Corps, on the First Army’s right, had a huge gap on its eastern flank where it had lost contact with the Seventh Army. The corps commander, SS Gruppenfuhrer Max Simon, tried to shore up his defense by turning the corps to face north. He deployed the 212th Volksgrenadier Division (actually a division HQ commanding an assortment of spare organizations and training units) along a series of woodlands south of Tiefenthal, anchored on the Tauber River in the west. This “division” defended the open plain southwest of Wurzburg and Ochsenfurt. Simon stiffened the backbones of these troops by infusing their formations with cadres of fanatic SS troops. The 116th Cavalry Squadron located the 212th Volksgrenadier Division and alerted General Blakeley to its presence. The German position denied the Americans use of the highway passing through Tiefenthal. The Ivy Division commander decided to send the 12th Infantry to destroy this makeshift defensive line.9

CT 12 passed the order to the 2nd Battalion to eliminate the Germans located in the woods next to the hamlet of Simmringen. The regiment beefed up the battalion with ten tanks and four tank destroyers. Lt. Col. John Gorn gave E Company the mission of leading the attack into the Simmringen Woods. Rather than charge into the forest, he instructed Bill to make initial contact with the enemy then determine where they set up their “kill zone.”10

Bill briefed his officers and sergeants on his plan of attack. He wanted the scouts well forward to locate the enemy defenders without getting the whole company pinned down. Before the meeting broke up, one of the platoon sergeants asked, “Who do you want on the BAR?”

The Browning Automatic Rifle provided the rifle squads with their heaviest firepower. It fired a standard .30 caliber cartridge in automatic mode from a twenty-round magazine. The BAR fired at a high rate but frequent magazine changes reduced its volume of fire. Its chief advantage came from the fact that a gunner could fire the BAR from a prone position or sling it over his shoulder while walking. That gave the squads an automatic weapon in the assault.

Most of the BARs had been assigned to veteran infantrymen but the recent reorganization meant that a few had to be given to new men. Bill thought for a moment then recalled one soldier who had just joined the company. The kid had the bravado of someone who had never been under fire. The first thing out of his mouth was “When do I get a chance to kill Germans?” While the regiment remained in reserve or in a forward assembly area, he complained about not seeing any action. His bluster annoyed the company’s veterans, including its commander, who had long since forgone their zeal for shooting it out with the Germans.

“Let the new hot shot kid take one. Let’s see what he can do,” Bill answered.

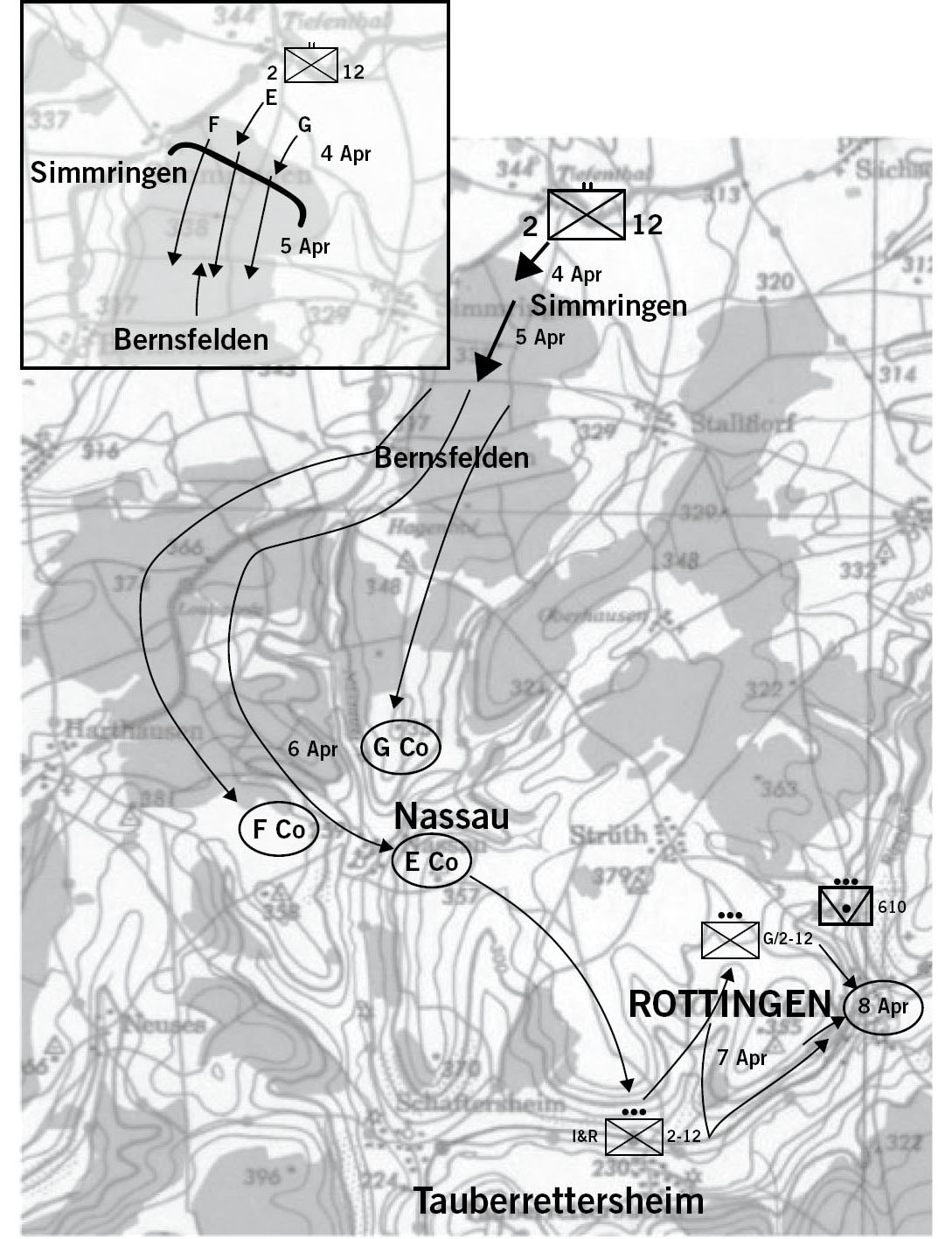

The battalion moved out by 1300 hours. An hour later, E Company assumed its attack formation and passed through Tiefenthal where the LD had been drawn. G Company followed on their left (east) flank. As they approached Simmringen Woods, the scouts started taking fire. Bill could see that the fire only came from a German forward outpost, nothing that a little supporting fire from the mortars and tanks could not handle. He continued pressing ahead. As E Company neared the edge of the woods, Bill perceived that the German commander had set his defense inside the woods rather than along its edge. The enemy chose to sacrifice good observation and long fields of fire from the tree line, so his men would not be easily targeted by the American tanks, mortars, and machine guns. After conferring with Colonel Gorn, E and G Companies advanced into Simmringen Woods.11 (See Map XIV)

The rifle platoons and squads compressed their formations once the company entered the woods, otherwise the limited visibility would complicate command and control. Bill brought all three platoons on line to present maximum firepower forward. Platoons tied in with each other’s flanks and connected with G Company on the left. As soon as the company was lined up to Bill’s satisfaction, he gave the signal to advance. An attack in thick woods called for cautious movement and close supervision to maintain control. Bill and his command group adhered to doctrine and followed closely behind the platoon at the center of the line.12

E and G Companies barely got started before the Germans opened fire from a series of bunkers. The men hit the dirt. Bill shouted to his men to return fire, and E Company responded with a massive volley of small arms fire. Just as the Americans got the upper hand in the volume of fire, the new soldier with the BAR stepped away from the cover of the tree that protected him, leveled the BAR from his hip, and started to spray .30 cal. rounds into the dirt.

Bill watched in horror as a German machine gun instantly shifted in the direction of the BAR and fired a quick burst. The kid fell dead, taking the BAR out of action. “Dammit!” Bill shouted. The eager recruit lasted less than a minute once the shooting started.

Bill turned his attention from the lost man back to the battle. He searched for a weak point to attack while his platoons traded shots with the enemy. The collective fire from the rifles and two light machine guns helped suppress the defenders’ fire and took out some of the enemy. The riflemen crawled through the underbrush but the attack moved forward slowly.

Bill brought up a platoon of tanks but the woods were too dense for them to be of much use. Bill scouted up and down the line looking for a gap in the German entrenchments. He found none. To E Company’s left, 1st Lt. Clarence Dunn, G Company commander, found no gaps farther east, either. The two lieutenants reported back to Colonel Gorn that they faced a cohesive enemy front stretching from one side of the Simmringen Woods to the other. Their report and the interrogation of prisoners revealed the full scope of CT 12’s situation. It faced an enemy force of equivalent size with companies bolstered by platoons of SS troops.13

Given this information, Colonel Gorn and Colonel Chance agreed to halt the attack and prepare for a more deliberate assault on April 5. The 2nd Battalion prepared a hasty defense for the night. Bill and Lieutenant Dunn tied their two companies together to prevent any German infiltration. Working with the two forward companies, the H Company Commander, Lieutenant Hackett, set his machine guns to cover the frontline with FPLs. Bill positioned his own M1919 machine guns to fill the gaps in his front. E Company had only pushed a few hundred meters into the woods, so the men had to dig foxholes with only a couple hundred meters separating them from the Germans. Everyone spent a sleepless night watching and listening.

After bedding down the troops, the battalion staff and company commanders planned the next attack. Colonel Gorn decided to slide F Company into the woods on E Company’s right. He wanted the full force of the battalion to drive the enemy from the woods. The battalion now had two platoons of Sherman tanks and one platoon of Stuart light tanks attached. Earlier in the day, the thickness of the woods had kept the tanks out of the action. During his recon Bill noticed that four narrow logging trails ran north to south through Simmringen Woods. These trails could accommodate the American tanks. Gorn organized the tanks into four columns, one per logging trail. He also split the rifle companies between the trails—G on the left (east), F on the right (west), and E in the center. The Ammunition & Pioneer (A&P) Platoon distributed satchel charges to the infantry companies to help them take out the enemy bunkers. All three company commanders coordinated plans to stay linked during the attack.14

At 0730 hours on April 5, E Company’s riflemen rose from their foxholes and formed on line. Bill ordered them forward, keeping the platoons in tight formation. He wanted to deliver highly concentrated fire when they hit the enemy defense. F and G Companies moved out at the same time. The scouts crept forward ahead of the platoons. E Company hit the enemy first. The Germans opened fire with machine guns and rifles from bunkers and foxholes only two hundred to three hundred meters deeper in the woods.15

Bill crawled forward to spot the enemy positions. He located a German bunker close to a logging trail. That would be his first target. He crawled back to the nearest rifle platoons and brought them forward. The platoons advanced using “assault fire.” As Army doctrine explained it, “Automatic riflemen and riflemen, with bayonets fixed, all taking full advantage of existing cover such as tanks, boulders, trees, walls, and mounds…fire as they advance at areas known or believed to be occupied by hostile personnel. Such fire is usually delivered from the standing position and is executed at a rapid rate.” In this case, Bill ordered the platoons to crawl forward rather than charge the bunker upright but he told them to keep up the same rate of fire. The platoons responded with a full fusillade of .30 cal. rounds. Bullets tore through the underbrush like a horizontal rain shower, forcing the defenders’ heads down.16

Bill scurried over to the logging trail and escorted one of the medium tanks forward. He pointed to the location of the bunker then let the tank maneuver into a firing position. A German Panzerfaust could knock out the Sherman but the torrent of bullets made it impossible to use one. The tank fired its main gun into the bunker, killing the machine gun crew. With the machine gun out of action, one of the American soldiers worked his way to the side of the casemate and tossed in a satchel charge. Seconds later a huge explosion blew out the bunker’s interior and killed the Germans inside.

The infantrymen then opened fire on the next fortification in the line. With the Germans pinned inside, the tanks moved up without worrying about a Panzerfaust. As soon as it got close enough to sight the breastwork, it fired a round through its opening. Quickly, an infantryman tossed a satchel charge into the second bunker.

By this time, the light machine gunners had to pour water from their canteens over their barrels to cool them. Continuing to use the same techniques it had against the first two bunkers, E Company took out a third then a fourth position.

Lieutenant Touhy, Bill’s XO, kept calling for more ammunition to fill the company’s insatiable demand. To meet it, the battalion loaded two-and-a-half-ton trucks with crates of .30 cal. ammunition, some in belts for the machine guns, others loose for the M1 rifles, and sent them to the edge of the woods. The A&P Platoon unloaded the trucks, broke down the crates, and crammed loose rounds into eight-round magazines. The ammo bearers draped bandoliers stuffed with magazines over their shoulders and hefted green ammo cans filled with belted rounds. They ran forward to the platoon sergeants and dropped off the ammo. The platoon sergeants broke open the ammo cans then sent runners back and forth to the squads and machine gun crews to deliver the bandoliers and belts. Over and over it went.

Bill pressed the attack down the line. Riflemen, machine gunners, tank crews, and the soldiers carrying satchel charges worked together to suppress then destroy each bunker in turn. Instead of pinning the Americans down inside the woods, the German commander’s force was pinned inside its fortifications. The enemy force could not stop E Company from overwhelming it one position at a time.17

At 1045 hours, the terrain got too thick for the Shermans. The smaller Stuart tanks came forward to assist E Company. The attack progressed beyond the first line of bunkers but “was stopped time and time again because of the dense woods which caused the units to lose contact and to allow gaps to appear in our lines.” At one point resistance built up on E Company’s right flank. Later a buildup of Germans on the left stalled the attack. Nevertheless, Bill’s rifle platoons and those of F and G Companies continued to push deeper into the woods.18

The German defense crumbled under the relentless onslaught and methodical destruction of its entrenched positions. “Around noon the enemy began to surrender,” Bill reported. The German commander resorted to desperate measures to keep the battle from slipping away entirely. “At 1330 Jerry launched a counterattack at the crossroads with a force of 150 men. E and F Companies and the tanks fired continuously for ten minutes and stopped the attack.” The enemy assault amounted to a suicide charge straight into a storm of American fire. Bill later counted eighty-five enemy bodies near the crossroads.19

The battle raged into the late afternoon. The sound of the infantry “assault fire” rattled through the woods like snare drums at dress parade. The place reeked of spent ball propellant. Light machine gun crews switched barrels back and forth. Ammo bearers passed out more .30 cal. rounds. The enemy tried to form another counterattack but Bill called in mortar rounds on them and broke up the attack before it could get organized. The tanks stood nearby, ready to move up under the infantry’s intense protective fire and blast another bunker.

Word filtered up the chain of command that 2nd Battalion had a major fight on its hands. General Milburn, XXI Corps Commander, stopped at the regimental CP at 1440 hours to get a briefing. Late in the day, the CP called Bill back to meet with a different senior officer. He worked his way to a spot away from enemy fire where he found a jeep carrying the 4th Infantry Division’s Ammunition Officer.

The lieutenant reported to the staff major. “Sir, what do you need?”

“Lieutenant, I’m here to find out what the Hell is going on.”

“Sir, we’re taking out a line of enemy bunkers inside the woods.”

“I see that but why do you need all that ammo?”

“We’re using suppressive fire to keep the Germans buttoned up while we take out their bunkers. Is there a problem?”

The major shook his head. “No. I was just curious about where all that ammo was going.”

“We’re putting it to good use.”

“That’s fine, Lieutenant, but do you know that you’ve exhausted the entire division’s stock of small arms ammunition?”

Bill shrugged then returned to the fight. The battle ended as darkness began descending over the woods. The company picked up a few prisoners late in the day. Bill pulled one of his soldiers to march the Germans back to the battalion collection point. The soldier he selected happened to be a Native American armed with a submachine gun. Bill told the soldier where to take the prisoners and ordered him to return as quickly as possible.

The soldier took charge of the prisoners and started marching them to the rear down a forest trail. A minute later, Bill heard a burst of fire from the submachine gun. Alarmed, he ran to the sound of the gunfire. He found the soldier standing over the German bodies a short distance down the trail. Steam hissed off the submachine gun’s barrel.20

“Why’d you shoot them?” Bill asked.

“They tried to escape,” the soldier replied.

Bill looked at the dead Germans. They had all fallen evenly spaced along the side of the trail. “What do you mean ‘tried to escape’? They’re all still in line.”

The Native American soldier shrugged. “They started to run, so I shot ‘em.”

Bill fumed. This looked like an obvious case of murdering prisoners but he had no way of disproving the soldier’s lame excuse.

Incidents of frontline retribution were not common but not unknown. Soldiers, still flush from battle, who had charge over prisoners sometimes chose to avenge lost buddies rather than send the prisoners back to sit out the rest of the war in a camp. Some commanders chose to look the other way. Why charge a soldier with murder for killing the enemy? Bill did not share that sentiment. He still saw the German soldiers as people, even in the heat of battle. He had no way of prosecuting the soldier but he made up his mind never to trust him with prisoners, again.

As he walked away Bill looked back at the dead Germans and the Native American soldier. A question popped into his head. Did those Germans die for Hitler or Custer?

Measured by distance covered, the attack of April 4–5 accomplished little, just a few hundred meters. In terms of comparative losses, the battle of Simmringen Woods had been one of the battalion’s most successful engagements. E Company only had four men killed in action, including the over-eager replacement with the BAR the day before. Over the two days, it had killed well over a hundred Germans and captured dozens more. In the process of inflicting those losses, the 2nd Battalion rooted out a large, entrenched enemy force from terrain that favored the defender. What a difference from the bloody days in the Cotentin Peninsula when dead GIs marked every few meters of advance. Bill would later regard April 5 as one of his best days in command.21

The men spent another anxious night next to the enemy. They had driven back every German defender they had faced but only cleared the first of their four objectives. The question remained: how tough would the fight be on April 6?22

The answer came shortly after the attack resumed at 0630 hours. The scouts pushed ahead of the company’s main body to locate the enemy front. They snuck forward but made no contact. By 0830 hours the company had advanced four hundred to six hundred meters without “meeting anything.” Colonel Gorn, guessing that the Germans had abandoned the woods, re-directed E and F Companies to Bernsfelden. F Company seized the town at 1100 hours while E Company overran Hagenhof, a small hamlet farther south. The two companies aligned on the Tiefenthal-Harthausen highway at noon. With E Company on the left side and F Company on the right, the two rifle companies marched southwest in attack formation. They swept the woods en route to Harthausen, meeting no resistance. Air reconnaissance had reported 200– 300 enemy fleeing south from the town earlier that morning. In mid-afternoon, the S-2 learned from prisoner interrogations that a German force had withdrawn to Nassau, the battalion’s final objective. Colonel Gorn ordered his rifle companies to change direction and proceed to Nassau. Bill reoriented his attack formation to the southeast and marched his company through more woods. By nightfall, it entered the town with F and G Companies positioned on the flanks. The German force had already pulled out. E Company covered seven kilometers on April 6, about ten times the progress of the day before. The lack of resistance proved that the Germans had fallen back to establish a new line along an east-west bend of the Tauber River.23 (See Map XIV)

Colonel Chance wanted to break through this new defensive barrier before the Germans could prepare it. He issued orders for the 2nd and 3rd Battalions to clear the zone north of the Tauber River while sending only one reinforced company from each battalion to seize seven crossing sites. Chance warned both battalions to be ready to attack in force across the river on short notice. Colonel Gorn tapped E Company to capture the three sites in the battalion’s sector: Tauberrettersheim, Rottingen, and Bieberehren.24

The regiment’s tactical plan had major shortcomings and did not comply with Army doctrine. River crossing operations called for “boldly and rapidly executed crossings,” the establishment of “local bridgeheads, and the crossing of follow-on units.” Colonel Chance planned for two companies to capture seven crossing sites spread over a sixteen-kilometer front. Even if Bill’s company could seize three separate river crossings in a day, he could only hold them with platoon-size forces—never mind establishing bridgeheads. The timid plan to capture just the crossing sites, without establishing bridgeheads on the far side, indicated that the division and regiment did not intend to attack over the Tauber River just yet. Colonel Gorn altered the plan in his zone by sending the regiment’s Raider Platoon and one platoon from G and F Companies to Tauberrettersheim, Rottingen, and Bieberehren, respectively. E Company would then relieve each platoon in succession or help drive out any Germans the platoons encountered.25

The patrols departed at 0700 hours on April 7. E Company moved south from Nassau shortly thereafter. They climbed the hill south of town then followed the contours of a ravine down to the Tauber River valley. Meanwhile, the Raider Platoon entered Tauberrettersheim by 1150 hours. The scouts found the bridge destroyed but discovered a serviceable ford in the same area. E Company approached the town ninety minutes later. All went well until a German 20mm anti-aircraft gun opened fire from the hill to their east. Bill may have had troubles orienting himself that morning. He reported his position on the hill above Shaftersheim while he was actually one hill farther east, above Tauberrettersheim. Fortunately, the German 20mm gun withdrew. The records do not say why, but the company likely returned fire with machine guns and mortar fire. E Company entered Tauberrettersheim and freed the Raider Platoon to continue its scouting mission.26

Bill left one of his platoons to guard the fording site then marched the rest of the company east, up the river valley, toward Rottingen. An elongated ridge, Hill 355, stood between Tauberrettersheim and Rottingen. The road between the river towns traveled up the southwestern slope of Hill 355. Bill used the hill to mask the company’s advance from the enemy occupying high ground across the river from Rottingen. On the way, they met the platoon from G Company that had been sent to seize the crossing site. The platoon had been driven back from the objective by German small arms fire from the town and the hills south of the river. Bill took control over the loose platoon to replace the one he left at Tauberrettersheim. Examining the town and enemy positions from Hill 355, he spotted a rail line running along the valley floor. German engineers had built an embankment to elevate the rail line coming into Rottingen from the southwest. The quick recon gave Bill an idea for attacking the town.

At 1508 hours, Bill requested an artillery strike on the Germans across the river. He brought forward an attached platoon of tank destroyers from the 610th TD Battalion at the same time. Their guns joined the 105mm guns of the artillery in pounding Rottingen and the enemy lurking in the woods south of town. He sent the G Company platoon around to the north side of Hill 355 where they could fire on the enemy inside the town. E Company’s remaining two platoons slipped down into the valley and moved northeast toward Rottingen. Bill had the men scrape the railroad embankment with their right shoulders as they advanced, shielding them from enemy observers on the opposite bank.

Around 1720 hours, the lead elements ran into German small arms fire. The G Company platoon replied with covering fire on Rottingen as Bill pushed his platoons forward. The lead rifle platoon stormed Burg Brattenstein on the southwestern edge of town. As the company got a toehold in Rottingen, some of Bill’s troops jerked a German soldier out of a nearby culvert. The prisoner told Bill that a company of SS troops, armed with two Panzerfausten apiece, occupied Rottingen. E Company pushed ahead in the dwindling daylight, going house-to-house to root out the enemy. The inexperienced Nazi troops failed to impress Bill with their fighting skills. “In the battle for the town the krauts used their panzerfausts as mortars shooting them up in the air with a total result of two dead chickens.”

Back in the regimental CP, Colonel Chance received a call from General Blakeley. The general said he wanted to give the troops a chance to rest before the next big push and cautioned against any further coordinated attacks. Blakeley’s guidance showed that he did not feel ready to launch a major offensive south of the Tauber River. Bill received word not to press the fight too hard. He halted the house-to-house fighting, figuring he had better chances to use supporting fire the next morning.27

Before the word got out, Private Max Gartenberg of New York City, who knew a little German, pounded on the door of a house. He demanded that the residents let him and a few other soldiers inside. A middle-aged man appeared at the door. “Wir sind anti-Nazi,” he said raising his hands. The family welcomed the Americans into their home.28

The troops were about to enjoy some German hospitality when another soldier ran in and announced, “The captain said we’re not to flush any more houses. This town is full of Jerries, and we’re not going to do anything more until the morning.” The disappointed troops said farewell to their hosts and rejoined the rest of the company on the west side of Rottingen.

The next morning, Colonel Gorn sent Lieutenant D. Smith’s platoon of Sherman tanks from B Company, 70th Tank Battalion to E Company. Bill used them to escort the infantry through the streets of Rottingen, providing the riflemen with extra firepower as they cleared the houses. Block by block, E Company ground its way through the town against light resistance. By mid-morning they had possession of most buildings.29

That morning, the company CP summoned Private Gartenberg to serve as a translator. “Inside an officer and a noncom were sitting with a big map stretched out between them. Opposite them sat a civilian. It was none other than my German host from the night before. He recognized me, too, and greeted me warmly.30

“What he was trying to say, I told the officers, was that in a stone house beside a stream there were SS men. My new friend pointed out the spot on the map.”

With the information from the civilian, Bill orchestrated the rest of the battle to clear the SS from Rottingen. He positioned crew-served weapons to cover the stone building then plotted artillery fire on the building and beyond to cut off the enemy’s line of retreat. On his order, the 105mm guns opened fire.

Private Gartenberg witnessed the rout. “Suddenly, the door opened, and men in dark uniforms started running out. A machine gun opened up out of nowhere, and men fell like berries shaken off a bush. There were at least a dozen I could see wounded…dying.”

Bill watched the action, too. “At 1000 the enemy could be observed withdrawing across the open fields to the east. One group ran directly into a prepared artillery barrage. A kraut fleeing from Rottingen dashed madly up a draw. A mortar barrage fell and he dove into a hole; one shell appeared to land directly into his hole and exploded. Miraculously, he had escaped death and he jumped out of his hole and raced out of sight.”31

Bill reported that E Company had finished clearing Rottingen shortly after noon. During the morning, Colonel Chance had pulled the rest of the 2nd Battalion off the line and replaced them with the 1st Battalion. B Company took over responsibility for Rottingen. Deuce-and-a-half trucks picked up E Company then drove them back to an assembly area near Stalldorf, seven kilometers back from the Tauber River.32

By the time Bill’s battalion pulled off the front, the regiment held most, but not all, of the seven crossing sites over the Tauber River. The five-day drive did not gain much ground. CT 12 had pushed the line a little more than ten kilometers south from the Simmringen Woods. In terms of attrition, the scales tipped markedly in CT 12’s favor. The 12th Infantry smashed the north-facing defensive line the XIIIth SS Corps had tried to form, and Gruppenfuhrer Simon had only hastily organized Kampfgruppen left along the Tauber River. Besides the heavy casualties it inflicted, the regiment swept up 493 prisoners. One soldier in the 1st Battalion made a huge haul on his own. He fell asleep on patrol one night in an enemy-held town. During the night, the German garrison woke him up to surrender. He brought in ninety-three prisoners the next day by himself. The rear detachments collected nearly as many loose German soldiers roaming the countryside as the three rifle battalions. By comparison, the regiment had only modest losses.33

The 2nd Battalion spent the next two days resting and taking care of their equipment. The tough fighting in early April came as a severe shock and disappointment to the veterans in the outfit. Men who had survived the Normandy bloodbaths or struggled through the Ardennes—twice—had hoped for an easy drive through Germany. The savage fighting in the Simmringen Woods dispelled that notion. There were still plenty of chances to be killed. With the war now drawing tantalizingly close to an end, many of the old hands began dwelling on their own survival, something they had not allowed themselves to do earlier.

Bill, still haunted by the premonition that he would never return home, steadfastly did his duty. Others chose a different course. Two of Bill’s veteran non-coms calculated that, if they deserted then were caught, the Army would throw the book at them. Normal punishment for desertion was thirty days of confinement. The prospect of waiting out the last month of the war in jail looked like a safer bet than risking death on the front line. The two slipped away from the company assembly area and spent a couple nights carousing in a nearby town. Just as they planned, the Military Police rounded them up and hauled them back to E Company.34

Bill saw through the sergeants’ plan. He could not tolerate non-coms deserting. Their infraction called for stern punishment, yet he did not want to lose two experienced soldiers. Besides, he hated to give them exactly what they wanted, confinement in the stockade safely tucked away from combat. Bill’s solution delivered punishment without rewarding the offenders. Instead of court-martialing them, he issued administrative punishment under Article 15 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice. He busted each sergeant down to the rank of corporal and docked both a month’s pay. One of the sergeants had a previous infraction, so Bill court-martialed him on the lesser charge of stealing government property. The two sergeants got the worst of both worlds. They would return to combat but would fight without earning any pay. The word spread quickly within E Company. There was no point deserting under Bill’s command.

While resting in Stalldorf, Bill found time to write a letter to Beth, his first in almost a week. The latest campaign weighed on his mind. “Really had a tough week this time…Some of my decisions have been difficult and some have been easy, but all in all it was a damn tough job.” The responsibility of commanding men in combat crept into his thoughts. “Made a few mistakes and probably have a few more lives on my hands—but that is an officer’s usual task.” Bill’s mind gravitated to reason and rational thinking. He used those faculties to manage the stress of ordering men to their deaths. “I really don’t feel guilty about some of the boys that have died doing the accomplishment of my orders, but I’ll always wonder if there could have been fewer losses.” He accepted that losses among his men were inevitable. As he noted once, A guy can get hurt out here. As long as he believed that his actions and decisions served a purpose and he had exercised sound judgment, Bill could bear the emotional strain without sliding into self-reproach. The ability to dissuade emotions and fear through rational thought was one of the traits that made him so suitable for combat command.35