One of the residual problems left to us from dualism is the problem of mental causation. Our first mind-body problem was, How can physical processes ever cause mental processes? But to many philosophers the other half of the question is even more pressing, How can anything as ethereal and insubstantial as mental processes ever have any physical effects in the real world? Surely the real physical world is “causally closed” in the sense that nothing from outside the physical world can ever have any causal effects inside the physical world.

By now, the reader will know that I do not think these are impossibly difficult questions, and that our acceptance of the Cartesian categories is what makes them seem difficult. However, there are a lot of fascinating problems that arise in the study of mental causation. Even if you accept my general account of mind-body relations, I think you will find some interesting issues about mental causation discussed in this chapter.

I. HUME’S ACCOUNT OF CAUSATION

We have to start with Hume. Just as when we talk about the mind in general there is no escaping Descartes, so when we talk about causation there is no escaping Hume. Hume’s account of causation is by far his most original, powerful, and profound piece of philosophy, and I think most philosophers would agree with me that it is one of the most impressive pieces of philosophical prose ever written in the English language. Whatever else you learn from this book, I would like you to learn something about Hume’s skeptical account of causation. (Of course, what follows is not intended as a substitute for reading the real thing—Hume’s Treatise, Book 1, Part 3—but what I will now tell you will give you a guide for making your way around the real territory).1 Here is how it goes:

Hume begins by asking what are the components of our reasoning considering cause and effect. In the twenty-first century we would put this in the form, What is the definition of “cause”? Hume says there are three components to our notion of causation:

Priority, by which he means the cause has to occur prior in time to the effect; causes cannot come after their effects.

Contiguity in space and time, by which he means the cause and effect have to be adjacent to each other. If I scratch my head in Berkeley and a building falls over in Paris, my scratching my head cannot be the cause of the building falling over unless there is a series of links in a “causal chain” between my head and the building in Paris.

Necessary connection, by which he means, in addition to priority and contiguity, the cause and effect must be necessarily connected in such a way that the cause actually produces the effect, the cause makes the effect happen, the cause necessitates the effect, or as Hume would summarize this, there is a necessary connection between cause and effect.

But, says Hume, when we begin to look at actual cases, we find that we cannot perceive any necessary connection. We observe that, for example, when I flip the light switch, the light goes on, and if I flip it again it goes off. I think there is a causal connection between flipping the switch A and the light going on B, but in fact all I can really observe is A followed by B. Hume presents the absence of necessary connection as if it were a sort of lamentable lack that we might overcome, as if by closer inspection we might discover a necessary connection. But he knows perfectly well that in the way that he has described the case, there could never be a necessary connection. For suppose I said that the necessary connection between flipping the switch and the light going on is the passage of electricity through the wire C, and I found some method of observing that, say through a metering device. But that would not help. For now I would have the flipping of the switch, the passage of the electricity, and the light going on, the sequence ACB. But I still would have no necessary connections between these three events. And if I found one, if I found apparent necessary connections between the switch A, the electricity C, and the light B, in the form of, let us say, the closing of the circuitry D, or the activation of the molecules in the tungsten filament E, these would still not be necessary connections. I would then have a sequence of five events, ADCEB, and these would require necessary connections between each. Hume’s first skeptical result is there is no necessary connection between the so-called cause and the so-called effect.

At this point Hume really takes off. He says that we should examine the underlying principles of cause and effect, and he discovers two principles: the principle of causation and the principle of causality. The principle of causation says every event has a cause. The principle of causality says like causes have like effects. These, as he correctly sees, are not equivalent. For it might be the case that every event had a cause though there was no consistency in what sort of effects any particular cause might have, and no consistency in what sort of causes any effect might have. And it might be the case that when there were causes and effects, like causes had like effects, even though not every event had a cause. But, says Hume, if we examine these two principles, the principle of causation and the principle of causality, we find a peculiar feature. They do not seem to be provable. They are not true by definition. That is, they are not analytic truths. So they must be synthetic empirical truths. But now, and this is the real cruncher of Hume’s argument, there is no way that we could establish them by empirical methods, because any attempt to establish anything by empirical methods presupposes exactly these two principles.

This is Hume’s most celebrated result. It is called the problem of induction, and here is how it is stated. If you think of deductive arguments, such as the argument:

Socrates is a man.

All men are mortal.

Therefore Socrates is mortal.

You can see that the argument is valid because the conclusion is already contained implicitly in the premises. There is nothing in the conclusion that is not in the premises. We could represent this diagrammatically by saying we go from premise to conclusion, P  C, where P > C. The premise always contains more information than the conclusion (or in a limiting case where we derive a proposition from itself, the premise is the same as the conclusion). Validity is guaranteed because there is nothing in the conclusion that is not already in the premises. But when we consider scientific or inductive arguments, such as an argument to prove our premise that all men are mortal, it seems we do not have this type of validity. For in the case of inductive arguments, we go from evidence E to hypothesis H. We say, for example, the evidence about the mortality of particular individual men provides evidence for, or supports, or establishes, the general hypothesis that all men are mortal. We go from evidence to hypothesis, E

C, where P > C. The premise always contains more information than the conclusion (or in a limiting case where we derive a proposition from itself, the premise is the same as the conclusion). Validity is guaranteed because there is nothing in the conclusion that is not already in the premises. But when we consider scientific or inductive arguments, such as an argument to prove our premise that all men are mortal, it seems we do not have this type of validity. For in the case of inductive arguments, we go from evidence E to hypothesis H. We say, for example, the evidence about the mortality of particular individual men provides evidence for, or supports, or establishes, the general hypothesis that all men are mortal. We go from evidence to hypothesis, E  H, but (and this is the difference from deduction) in the case of induction there is always more in the hypothesis than there was in the evidence. The hypothesis is always more than just a summary of the evidence. That is to say, E < H, E is less than H. In such a case, it might seem a shame that we ever used inductive arguments at all, but of course, they are absolutely essential, because how else would we establish the general propositions that form the premises of our deductive arguments? How would we ever establish that all men are mortal if we could not generalize from particular instances of mortal men, or from other sorts of evidence about particular cases, to the general conclusion that all men are mortal?

H, but (and this is the difference from deduction) in the case of induction there is always more in the hypothesis than there was in the evidence. The hypothesis is always more than just a summary of the evidence. That is to say, E < H, E is less than H. In such a case, it might seem a shame that we ever used inductive arguments at all, but of course, they are absolutely essential, because how else would we establish the general propositions that form the premises of our deductive arguments? How would we ever establish that all men are mortal if we could not generalize from particular instances of mortal men, or from other sorts of evidence about particular cases, to the general conclusion that all men are mortal?

When we go from evidence to hypothesis, when we say the evidence supports the hypothesis, or establishes the hypothesis, or confirms the hypothesis, we do not do this in an arbitrary or unwarranted fashion. On the contrary, we have some principles or rules R by which we go from evidence to hypothesis, and you might think of these as the rules of scientific method. So we do not go in an arbitrary fashion E  H, but we go E

H, but we go E  H on the basis of R. ER

H on the basis of R. ER  H. But now, and this is Hume’s decisive point, What is the ground for R? E, the evidence, we will suppose comes from actual observations. H is a generalization from the observations. But now, if we are to justify the move from E to H on the basis of R, what is the justification for R? And Hume’s answer is: any attempt to justify R presupposes R. What is R exactly? (And here is where the connection with causation and causality comes in.) R can be stated in a variety of ways. The most obvious way to state it is just to say that every event has a cause and like causes have like effects. Other ways are to say that unobserved instances will resemble observed instances, that nature is uniform, that the future will resemble the past. All of these Hume takes as more-or-less equivalent for these purposes. Unless we presuppose some sort of uniformity of nature, the uniformity of nature guaranteed by causality and causation, we have no ground for inductive arguments. But, and this is the crucial point, there is no ground for the belief in the uniformity of nature, because any such a belief would have to be grounded in induction, which in turn would have to be grounded in the uniformity of nature; and thus the attempt to ground the belief in the uniformity of nature would be circular.

H. But now, and this is Hume’s decisive point, What is the ground for R? E, the evidence, we will suppose comes from actual observations. H is a generalization from the observations. But now, if we are to justify the move from E to H on the basis of R, what is the justification for R? And Hume’s answer is: any attempt to justify R presupposes R. What is R exactly? (And here is where the connection with causation and causality comes in.) R can be stated in a variety of ways. The most obvious way to state it is just to say that every event has a cause and like causes have like effects. Other ways are to say that unobserved instances will resemble observed instances, that nature is uniform, that the future will resemble the past. All of these Hume takes as more-or-less equivalent for these purposes. Unless we presuppose some sort of uniformity of nature, the uniformity of nature guaranteed by causality and causation, we have no ground for inductive arguments. But, and this is the crucial point, there is no ground for the belief in the uniformity of nature, because any such a belief would have to be grounded in induction, which in turn would have to be grounded in the uniformity of nature; and thus the attempt to ground the belief in the uniformity of nature would be circular.

So far, Hume’s results are almost entirely skeptical. There is no such thing as necessary connection in nature, and there is no such thing as a rational basis for induction. Typical of Hume’s method, after he gets skeptical results, is that he then gives us reasons why we cannot accept these skeptical results and should just proceed as if skepticism had not been established. We are bound to continue with our old superstitions, and Hume is eager to explain to us exactly how.

When we were looking around for necessary connection, we did not find necessary connection in addition to priority and contiguity, but we did find another relation: the constant conjunction of resembling instances. We discovered that the thing we call the cause is always followed by the thing we call the effect. Just as a matter of fact about our living in the world, we discover that the things we call causes are always followed by the things we call effects. This constant repetition in our experience, this constant conjunction of resembling instances, gives rise to a certain expectation in our minds whereby when we perceive the thing we call the cause we automatically expect to perceive the thing we call the effect. It is this “felt determination of the mind” to pass from the perception of the causes to the lively expectations of the effect, and from the idea of the cause to the idea of the effect, that gives us the illusion that there is something in nature in addition to priority, contiguity, and constant conjunction. This felt determination of the mind gives us the conviction that there are necessary connections in nature. But that conviction is nothing but an illusion. The only reality is the reality of priority, contiguity, and constant conjunction. Causation on Hume’s account is literally just one damn thing after another. The only point is that there is a regularity in the way one thing follows another, and this regularity gives us the illusion that there is something more. But the necessary connection we think exists in nature is entirely an illusion in the mind. The only reality is regularity.

The existence of the regularity in previously observed cases, however, is no ground whatever for supposing that the next case will resemble the preceding cases. It is in no way a solution of the problem of induction. It gives us the illusion that we can solve the problem of induction because we think that with the felt determination of the mind we have discovered a necessary connection. But the necessary connection is entirely in our mind, it is not in nature itself. In effect then, Hume copes with the problem of induction by showing how causality is prior to causation. The existence of regularities (causality) gives us the illusion of necessary connection, and the illusion of necessary connection gives us the conviction that every event has a cause (causation).

Hume’s legacy about causation, then, involves at least two fundamental principles. First, there is no such thing as necessary connection in nature. And second, what we find in nature, in place of causal connections, are universal regularities. Hume’s skepticism about necessary connection does not lead him to say there is no fact of the matter at all about causation. Rather, there is a fact of the matter, but it is not what we expected. We expected there to be a causal link between the cause and the effect, but what we in fact find is a sequence of events that instantiate universal laws. These two features have influenced the discussion of causation to this day. Most philosophers think that there are no causal connections in nature, and that any particular causal connection has to instantiate a universal law. Most of them are eager to point out that the terms in which the law is stated need not be the same as the terms that describe the incidents of the original causal relation. Thus, if I say, “The thing John did caused the phenomenon that Sally saw,” and suppose John put the pot of water on the stove and turned the heat on, and Sally saw water boiling in the pot, then it would be true that the thing that John did caused the phenomenon that Sally saw, but there would be no law mentioning John and Sally or even putting and seeing. The scientific laws will be about such things as water pressure when water is heated in the Earth’s atmosphere.

Hume’s skepticism about induction has been less influential on contemporary philosophy than his regularity theory of causation. I think that most philosophers today think that Hume can be answered, and the standard textbook answer is that Hume mistakenly supposed that inductive arguments should meet deductive standards. He supposes there is something missing in an argument that proceeds by inductive methods on the basis of evidence to support a conclusion, because the premises do not entail the conclusion in the manner of the deductive argument. It is, on the view of contemporary philosophers, as if somebody said “My motorcycle is not a good motorcycle because it does not get good marks in a dog show.” Motorcycles are not the same as dogs nor should they be judged by the standards by which we judge dogs. It is exactly the same sort of mistake to suppose that inductive arguments should be judged by deductive standards. By deductive standards there are valid deductive arguments, and by inductive standards there are valid inductive arguments. It is a mistake to confuse the one with the other.

Indeed, on one standard contemporary view, even this is conceding too much to Hume. The idea that there are even two styles of arguments, induction and deduction, is already a source of confusion. There are just deductive arguments, and one way to proceed in the sciences is called the hypothetico-deductive method. One forms a hypothesis, deduces a prediction, and then tests the hypothesis by testing to see if the prediction comes true. To the extent that the prediction comes true, we say that the original hypothesis is confirmed or supported. To the extent that it does not come true, we say that the hypothesis is disconfirmed or refuted. There is no flat opposition between induction and deduction. Rather, so-called induction is a matter of testing hypotheses by experiment and other sorts of evidence. And a typical way of testing a hypothesis is to deduce the consequences of the hypothesis and then see if those consequences can meet certain experimental tests. For example, the law of gravity would predict that a body would fall a certain distance within a certain time. Having made this deduction we then test the hypothesis by seeing whether objects do in fact fall this distance in that amount of time.

II. DO WE NEVER EXPERIENCE CAUSATION?

I said earlier that I have a great admiration for Hume's achievement in his analysis of necessary connection and his regularity theory of causal relations. But I also have to say that I think the theory is disastrously mistaken and that it has had a very bad effect on subsequent philosophy. I am not in this book going to undertake a general critique of Hume's account of causation and induction but shall just focus on those features that are essential for the philosophy of mind. Hume’s chief negative result about necessary connection can be stated in one sentence: there is no impression of necessary connection; that is, there is no experience of force, efficacy, power, or causal relation. Is that right? Does that sound plausible to you? I have to confess that it does not seem at all plausible to me. I think that we perceive necessary connections pretty much throughout our waking life and I want to explain how.

When we have perceptual experiences, or when we engage in voluntary actions, as we saw in our discussion of intentionality, there is a causally self-referential condition in the conditions of satisfaction of the intentional phenomena. The intention in action is only satisfied if it causes the bodily movement, the perceptual experience is only satisfied if it is caused by the object perceived. But in both of these cases it is quite common, though of course not universally true, that we actually experience the causal connection between the experience, on the one hand, and objects and states of affairs in the world, on the other. If you have any doubts about this just raise your arm. Clearly there is a distinction between the experience of your raising your arm and your experience of someone else raising it. As I mentioned in chapter 5, the neurosurgeon, Wilder Penfield, found that he could cause his patient’s arm to move by stimulating the neurons in the motor cortex with microelectrodes. Invariably the patients said something such as “I didn’t do that, you did.”2 Now clearly this experience is different from actually voluntarily raising one’s arm. In the normal case, where you raise your arm intentionally, you actually experience the causal efficacy of the conscious intention-in-action producing the bodily movement. Furthermore, if somebody bumps into you, you experience a certain perception, but you do not experience that perception as caused by you. You experience it as actually caused by the person’s body banging into you. So in both of these cases, in both action and perception, it seems to me quite common, indeed normal, that we perceive a causal connection between objects and states of affairs in the world and our own conscious experiences. In the case of action we experience our conscious intentions-in-action causing bodily movements. In the case of perception we experience objects and states of affairs in the world causing perceptual experiences in us.

I think Hume was looking in the wrong place. He was looking in a detached way at objects and events outside of him and he discovered that there was no necessary connection between them. But if you think about the character of your actual experiences it seems to me quite common that you experience yourself making something happen (that is an intentional action), or you experience something making something happen to you (that is a perception). In both cases it is quite common to experience the causal connection.

Elizabeth Anscombe (in lectures) gave a good example of this. Suppose I am sitting here at my desk and a car backfires outside and it makes me jump. In this case I actually experience my involuntary movement as caused by the loud noise I heard. I do not have to wait for the conjunction of resembling instances. In this case I actually experience the causal nexus as part of my sequence of conscious experiences.

So far, these experiences would only give us a causal relation between our own experiences and the real world, but we want to be able to discover the same relation in the real world apart from our experiences. It seems to me not at all difficult to extend the conception of causation that we get from our own experiences to objects and states of affairs in the world that exist and interact with each other in ways that are totally independent of our experiences. The effect that I personally create when I cause the car to move by pushing it is an effect I can observe when I observe you pushing it. But the causal relation is the same whether I am pushing the car or I am observing you pushing the car. Furthermore, I can then extend this to the case where there are no agents involved at all. If I see one car pushing another car I see the physical force of the first as causing the second to move. So it seems that in addition to our actual experience of causation we can easily extend the notion of causation to sequences of events in the world that do not contain our experiences or for that matter anybody else’s experiences. After all, causal relations involving human beings are only a tiny portion of causal relations in the universe. The point for the present discussion is that the same relation we experience when we make something happen or when something makes something happen to us, can be perceived to exist even when no experiences are involved in the causal relation.

There is nothing self-guaranteeing about our experience of causation. We could in any particular case be mistaken. But this possibility of error and illusion is built into any perceptual experience at all. The point for this discussion is that the experience of causation is no worse than any other perceptual experience.

I I I. MENTAL CAUSATION AND THE CAUSAL CLOSURE OF THE PHYSICAL

Let us suppose that I am right so far—that we do have the experience of causation as part of our normal waking consciousness, and that causation is a real relation in the real world. All the same, there seems to be a special problem about mental causation. Here is the problem: if consciousness is nonphysical, then how could it ever have a physical effect such as moving my body? Nonetheless, it seems in our experience that our consciousness does move our bodies. I consciously decide to raise my arm, and my arm goes up. Yet at the same time we know that there is another story to be told about the raising of the arm that has to do with neuron firings in the motor cortex, the secretion of acetylcholene at the axon end plates of my motor neurons, the stimulation of the ion channels, the attack on the cytoplasm of the muscle fiber, and eventually the arm rises. So if there is a story to be told about the effect of consciousness at the level of the mind, how does it fit with the story to be told about the chemistry and physiology at the level of the body? Worse yet, even supposing we did have a role for mental causation, that the mind did play a causal role in producing our bodily behavior, that seems to get us out of the frying pan and into the fire, because now it looks like we have too many causes. It looks like we have what philosophers call “causal overdetermination.” It looks like there would be two separate sets of causes making my arm go up, one having to do with neurons, and the other one having to do with conscious intentionality.

We can now summarize the philosophical problem about mental causation with some precision: if mental states are real, nonphysical states, it is hard to see how they could have any effects on the physical world. But if they do have real effects on the physical world, then it looks like we will have causal overdetermination. Either way it seems we cannot make sense of the idea of mental causation. There are four propositions that taken together are inconsistent.

1. The mind-body distinction: the mental and the physical form distinct realms.

2. The causal closure of the physical: the physical realm is causally closed in the sense that nothing nonphysical can enter into it and act as a cause.

3. The causal exclusion principle: where the physical causes are sufficient for an event, there cannot be any other types of causes of that event.

4. Causal efficacy of the mental: mental states really do function causally.3

These four together are inconsistent. One way out is to give up 4, but this amounts to epiphenomenalism. As Jaegwon Kim writes, “If this be epiphenominalism let us make the most of it.”4

In general, as we have seen over and over, when you have one of these impossible philosophical problems it usually turns out that you were making a false assumption. I believe that is the case in the present instance. The mistake is expressed in proposition 1, the traditional mind-body distinction. I said in chapter 4 that this mistake arises from supposing that if there is a level of description of brain processes at which they contain real and irreducible sequences of conscious states, and there is another level of description of brain processes at which they are purely biological phenomena, and the states of consciousness are not ontologically reducible to the neurobiological phenomena, then these two levels must be separate existences. We saw in chapter 4 that this is a mistake. The way out of this dilemma is to remind ourselves of a result we achieved in that chapter: the reality and irreducibility of consciousness do not imply that it is some separate type of entity or property “over and above” the brain system in which it is physically realized. The consciousness in the brain is not separate entity or property; it is just the state that the brain is in.

Our traditional vocabulary makes it almost impossible to state this point. If we say that the mental is irreducible to the physical then it looks like we are accepting dualism. But if we say that the mental just is physical at a higher level of description, then it looks like we are accepting materialism. The way out, to repeat a point I have made over and over, is to abandon the traditional vocabulary of mental and physical and just try to state all the facts. The relation of consciousness to brain processes is like the relation of the solidity of the piston to the molecular behavior of the metal alloys, or the liquidity of a body of water to the molecular behavior of the H2O molecules, or the explosion in the car cylinder to the oxidization of the individual hydrocarbon molecules. In every case the higher-level causes, at the level of the entire system, are not something in addition to the causes at the microlevel of the components of the system. Rather, the causes at the level of the entire system are entirely accounted for, entirely causally reducible to, the causation of the microelements. That is as true of brain processes as it is of car engines, or of water circulating in washing machines. When I say that my conscious decision to raise my arm caused my arm to go up, I am not saying that some cause occurred in addition to the behavior of the neurons when they fire and produce all sorts of other neurobiological consequences, rather I am simply describing the whole neurobiological system at the level of the entire system and not at the level of particular microelements. The situation is exactly analogous to the explosion in the cylinder of the car engine. I can say either the explosion in the cylinder caused the piston to move, or I can say the oxidization of hydrocarbon molecules released heat energy that exerted pressure on the molecular structure of the alloys. These are not two independent descriptions of two independent sets of causes, but rather they are descriptions at two different levels of one complete system. Of course, like all analogies, this one only works up to a certain point. The disanalogy between the brain and the car engine lies in the fact that consciousness is not ontologically reducible in the way that the explosion in the cylinder is ontologically reducible to the oxidization of the individual molecules. However, I have argued earlier and will repeat the point here: the ontological irreducibility of consciousness comes not from the fact that it has some separate causal role to play; rather, it comes from the fact that consciousness has a first-person ontology and is thus not reducible to something that has a third-person ontology, even though there is no causal efficacy to consciousness that is not reducible to the causal efficacy of its neuronal basis.

We can summarize the discussion of this section as follows. There are supposed to be two problems about mental causation: First, how can the mental, which is weightless and ethereal, ever affect the physical world? And second, if the mental did function causally would it not produce causal overdetermination? The way to answer these questions is to abandon the assumptions that gave rise to them in the first place. The basic assumption was that the irreducibility of the mental implied that it was

something over and above the physical and not a part of the physical world. Once we abandon this assumption, the answer to the two puzzles is first that the mental is simply a feature (at the level of the system) of the physical structure of the brain, and second, causally speaking, there are not two independent phenomena, the conscious effort and the unconscious neuron firings. There is just the brain system, which has one level of description where neuron firings are occurring and another level of description, the level of the system, where the system is conscious and indeed consciously trying to raise its arm. Once we abandon the traditional Cartesian categories of the mental and the physical, once we abandon the idea that there are two disconnected realms, then there really is no special problem about mental causation. There are, of course, very difficult problems about how it actually works in the neurobiology, and for the most part we do not yet know the solutions to those problems.

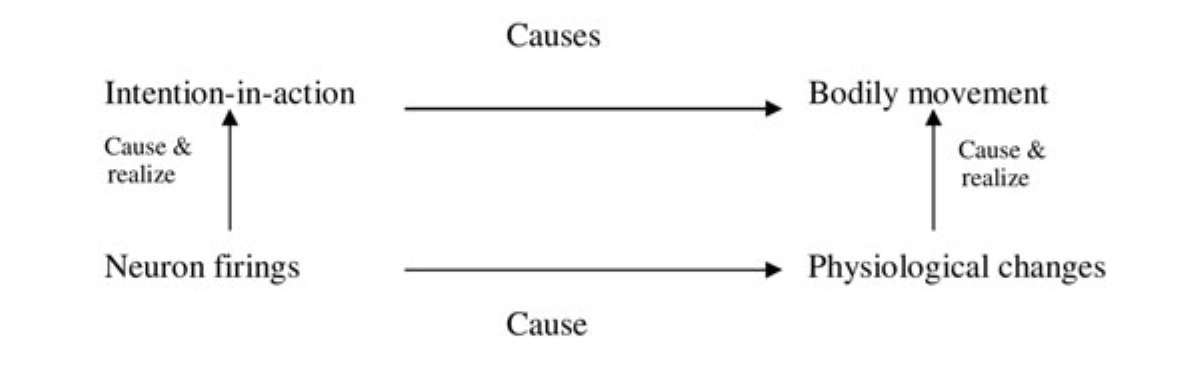

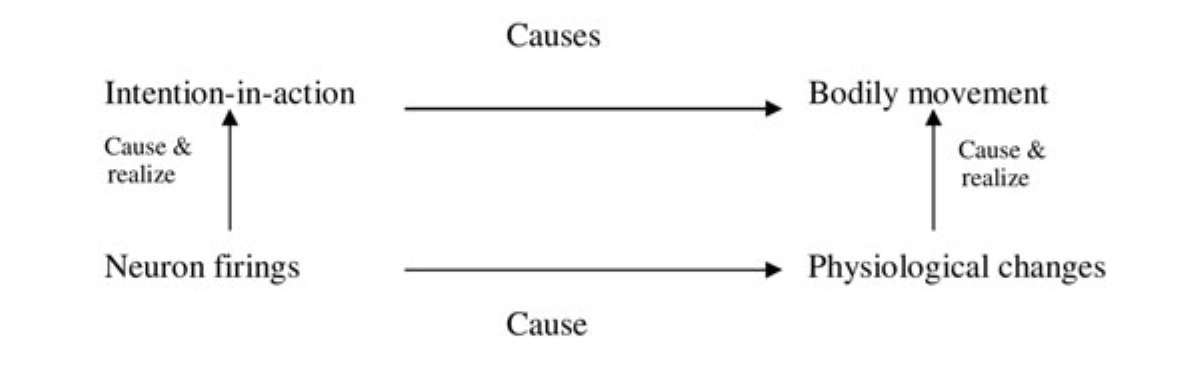

One way to represent these relation is in the following sort of diagram, where the top level shows the intention-in-action causing a bodily movement and the bottom level shows how it works in the neuronal and physiological plumbing. At each step the bottom level causes and realizes the top level:

Such diagrams are useful pedagogically, but they are misleading if they suggest that the mental level is on top, like the frosting on the cake. Maybe a better diagram is one where the conscious intention is shown as existing throughout the system and not just on top. In this one the circles represent neurons and the shading represents the conscious state as spread through the system of neurons:

IV. MENTAL CAUSATION AND THE EXPLANATION OF HUMAN BEHAVIOR

Throughout this book we have seen that there are two somewhat different types of philosophical problems surrounding the issues in the philosophy of mind. On the one hand there are the traditional problems of the form, How is such a thing possible at all? How is it possible that brain states can cause consciousness, for example. But there are also questions of the form, How does it work in real life? What is the actual structure and function of human consciousness? In this chapter we have examined exactly this distinction between the, How is it possible that there can be mental causation at all? question and the, How does it function in real life? question. I want to conclude the

chapter by saying at least a little bit about how mental causation functions in real life. Understanding the answer to this question is absolutely essential to understanding ourselves as human beings, for when we engage in voluntary human actions we typically engage on the basis of reasons and these reasons function causally in explaining our behavior, but the logical form of the explanation of human behavior in terms of reasons is radically different from standard forms of causation. I want now to explain some of these differences.

In a typical case of the ordinary nonmental causation we say such things as “The collapse of the freeway was caused by the earthquake.” But if you contrast that with an explanation that we typically give of our own actions (and it is always a good idea to consider your own case so you see how intentional causation functions in your own life), we see that the logical structure of the explanation is radically different. Suppose I say, “I voted for Bush in the last election because I wanted a better educational policy.”

If you look at the first explanation, the explanation of the collapse of the freeway, you see that it has several interesting logical features. First, the cause states a sufficient condition for the occurrence of the effect in that context. That is, in that particular context, given the structure of the freeway, and given the forces generated by the earthquake, once the earthquake occurred, the freeway had to collapse. Second, there are no purposes or goals involved, the earthquake and the collapse are just events that occur. Third, though the explanation, like any speech act, contains an intentional content, the intentional content itself does not function causally, rather, the intentional content “earthquake” or “there was an earthquake,” simply describes a phenomenon but does not cause anything. Now, these three conditions are not present in the explanation of my voting behavior. In my case the explanation did not state sufficient conditions. Yes, I wanted an improvement in education; yes, I thought Bush would be better for education than Gore; but all the same, nothing forced me to vote the way I did. I could have voted for the other guy, all other conditions remaining the same. Second, you will not understand the explanation unless you see that it is stated in terms of the goals of the agent. The notions of goals, aims, purposes, teleology, etc., are essentially involved in this type of explanation. Indeed the actual explanation I gave is incomplete. We only understand the claim that an agent did A because he wanted to achieve B if we assume that the agent also believed that doing A would produce B, or at least make it more likely that B occur. And third, it is absolutely essential to these explanations in terms of intentional causation that we understand that the intentional content that occurs in the explanation, for example, I wanted a better educational policy, actually occurs in the very cause whose specification explains the behavior we are trying to explain.

All of these three features—the presupposition of freedom, the requirement that an explanation of action has to have the specification of a goal or other motivator, and the functioning of intentional causation as part of the explanatory mechanism—are quite unlike anything in standard explanations of natural phenomena such as earthquakes and forest fires. All three are parts of one much larger phenomenon, rationality. It is essential to see that the functioning of human intentionality requires rationality as a structural constitutive organizing principle of the entire system. I cannot exaggerate the importance of this phenomenon for understanding the differences between the naturalistic explanations we get in the natural sciences and the intentionalistic explanations we get in the social sciences. In the surface structure of the sentences the following explanations look very much alike:

1. I made a mark on the ballot paper because I wanted to vote for Bush.

2. I got a stomachache because I wanted to vote for Bush.

Though the surface structure is similar, the actual logical form is quite different. Number 2 just states that an event, my stomachache, was caused by an intentional state, my desire. But number 1 does not state a causally sufficient condition, and makes sense only within the context of a presupposed teleology.

Such explanations raise a host of philosophical problems. The most important of these is the problem of free will, and I turn to that in the next chapter.

C, where P > C. The premise always contains more information than the conclusion (or in a limiting case where we derive a proposition from itself, the premise is the same as the conclusion). Validity is guaranteed because there is nothing in the conclusion that is not already in the premises. But when we consider scientific or inductive arguments, such as an argument to prove our premise that all men are mortal, it seems we do not have this type of validity. For in the case of inductive arguments, we go from evidence E to hypothesis H. We say, for example, the evidence about the mortality of particular individual men provides evidence for, or supports, or establishes, the general hypothesis that all men are mortal. We go from evidence to hypothesis, E

C, where P > C. The premise always contains more information than the conclusion (or in a limiting case where we derive a proposition from itself, the premise is the same as the conclusion). Validity is guaranteed because there is nothing in the conclusion that is not already in the premises. But when we consider scientific or inductive arguments, such as an argument to prove our premise that all men are mortal, it seems we do not have this type of validity. For in the case of inductive arguments, we go from evidence E to hypothesis H. We say, for example, the evidence about the mortality of particular individual men provides evidence for, or supports, or establishes, the general hypothesis that all men are mortal. We go from evidence to hypothesis, E  H, but (and this is the difference from deduction) in the case of induction there is always more in the hypothesis than there was in the evidence. The hypothesis is always more than just a summary of the evidence. That is to say, E < H, E is less than H. In such a case, it might seem a shame that we ever used inductive arguments at all, but of course, they are absolutely essential, because how else would we establish the general propositions that form the premises of our deductive arguments? How would we ever establish that all men are mortal if we could not generalize from particular instances of mortal men, or from other sorts of evidence about particular cases, to the general conclusion that all men are mortal?

H, but (and this is the difference from deduction) in the case of induction there is always more in the hypothesis than there was in the evidence. The hypothesis is always more than just a summary of the evidence. That is to say, E < H, E is less than H. In such a case, it might seem a shame that we ever used inductive arguments at all, but of course, they are absolutely essential, because how else would we establish the general propositions that form the premises of our deductive arguments? How would we ever establish that all men are mortal if we could not generalize from particular instances of mortal men, or from other sorts of evidence about particular cases, to the general conclusion that all men are mortal? H, but we go E

H, but we go E  H on the basis of R. ER

H on the basis of R. ER  H. But now, and this is Hume’s decisive point, What is the ground for R? E, the evidence, we will suppose comes from actual observations. H is a generalization from the observations. But now, if we are to justify the move from E to H on the basis of R, what is the justification for R? And Hume’s answer is: any attempt to justify R presupposes R. What is R exactly? (And here is where the connection with causation and causality comes in.) R can be stated in a variety of ways. The most obvious way to state it is just to say that every event has a cause and like causes have like effects. Other ways are to say that unobserved instances will resemble observed instances, that nature is uniform, that the future will resemble the past. All of these Hume takes as more-or-less equivalent for these purposes. Unless we presuppose some sort of uniformity of nature, the uniformity of nature guaranteed by causality and causation, we have no ground for inductive arguments. But, and this is the crucial point, there is no ground for the belief in the uniformity of nature, because any such a belief would have to be grounded in induction, which in turn would have to be grounded in the uniformity of nature; and thus the attempt to ground the belief in the uniformity of nature would be circular.

H. But now, and this is Hume’s decisive point, What is the ground for R? E, the evidence, we will suppose comes from actual observations. H is a generalization from the observations. But now, if we are to justify the move from E to H on the basis of R, what is the justification for R? And Hume’s answer is: any attempt to justify R presupposes R. What is R exactly? (And here is where the connection with causation and causality comes in.) R can be stated in a variety of ways. The most obvious way to state it is just to say that every event has a cause and like causes have like effects. Other ways are to say that unobserved instances will resemble observed instances, that nature is uniform, that the future will resemble the past. All of these Hume takes as more-or-less equivalent for these purposes. Unless we presuppose some sort of uniformity of nature, the uniformity of nature guaranteed by causality and causation, we have no ground for inductive arguments. But, and this is the crucial point, there is no ground for the belief in the uniformity of nature, because any such a belief would have to be grounded in induction, which in turn would have to be grounded in the uniformity of nature; and thus the attempt to ground the belief in the uniformity of nature would be circular.