BRITAIN AGAINST THE WALL

A nation in tension

When German aircraft began regular, nightly incursions over Britain on 5 June, their presence acted both as a shock and as a stimulant, besides a reminder to the populace that they no longer lived in an island. The inactivity of nine months’ ‘phoney war’ since September 1939 had led the British to dismiss the fears of wholesale death and destruction from aerial bombardment which had been prophesied before the war. That winter the scale of Civil Defence measures had been criticized as over-insurance. Now, with talk of imminent invasion on everyone’s lips, the appearance of men wearing LDV arm bands and calling themselves ‘parashots’; the drone of hostile aircraft, the bark of guns and the whistle and bang from an occasional bomb, they were prone to exaggerate and merge these manifestations of alarm into a mixture of despondency, panic, resolution, incredulity and euphoria when in danger.

By mid winter, at least half of London’s population had dismissed the likelihood of air raids so that, come June, over a third of the Capital’s households had not bothered to take air raid precautions except to comply with the compulsory blackout at night. Desperation now replaced complacency as feverish measures were taken to give protection against blast and fire. Only one in four knew how to deal with an incendiary bomb. Few shelters were designed for prolonged occupation and a large number were quite inadequate in every respect. Many people who had been evacuated from the cities in 1939 had returned home in the belief that the cities were well protected. Indeed, even as the guns were beginning to fire, there were those in rural areas who contemplated moving into the cities. The noise of war began to take its toll of people’s nerves because of loss of sleep in addition to the onset of fear. Disruption of a ‘normal’ life bred inefficiency and low morale for which the existing Civil Defence arrangements were unready.1

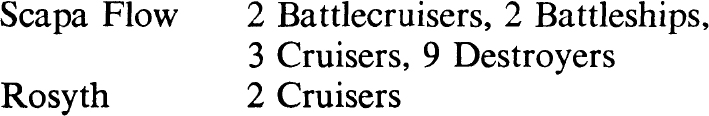

The underlying feeling of panic was to be detected among the residents in the area of Dover and Folkestone which was declared a Defence Area and made subject to compulsory evacuation if required. As the stauncher members of the community turned to caring for the men returning from Dunkirk, to manning the ships and docks, strengthening the ARP defences and patrolling the countryside and clifftops at night on the look out for paratroops, those of faint heart began to leave. There were many vehicles with plenty of petrol available. Some furniture vans were making four trips a day to the rural areas and numerous houses were soon left abandoned and locked up. Even as instructions were received to evacuate compulsorily 60 per cent of the school children from coastal towns between Great Yarmouth and Hythe, the mayors of Dover and Folkestone (J. R. Cairns and G. A. Gurr) were pleading with their townsfolk to show greater resolution and to stay put. Bankruptcy stared these towns in the face as the cross-Channel trade died overnight and industry moved out. Dover Council resisted a request by the Regional Commissioner for the South East (Sir Aukland Geddes) that it should nominate nine councillors to stay behind in the event of invasion. ‘What,’ asked Clr. John Walker, ‘would the Empire think if Dover Council did not stand firm?’2

If the populace had been aware of the extent of the dangers confronting them and the frailty of the nation’s defences, they might easily have given way to defeatism. As it was, Churchill’s intoxicating leadership kept them on an inflexible course striving towards survival and ultimate victory. But already Churchill and his advisers were worried by the direction of the enemy’s air effort. From 5 to 19 June, thirteen airfields, sixteen factories and fourteen ports had been attacked. None had been severely damaged, even though the enemy flew at the relatively low average altitude of 10,000 feet, and suffered the loss of eleven aircraft. Casualties were light despite a few bombs on outer London, the worst being nine killed in Cambridge by a single attack.3 But evidence was accumulating of German possession of a sophisticated radio beam device called Knickebein which would permit the Germans to drop bombs within 400 yards of any point in the country. Some of the German flights, as has already been explained, were intended to develop the skills of picked crews in its application.4

A false lead

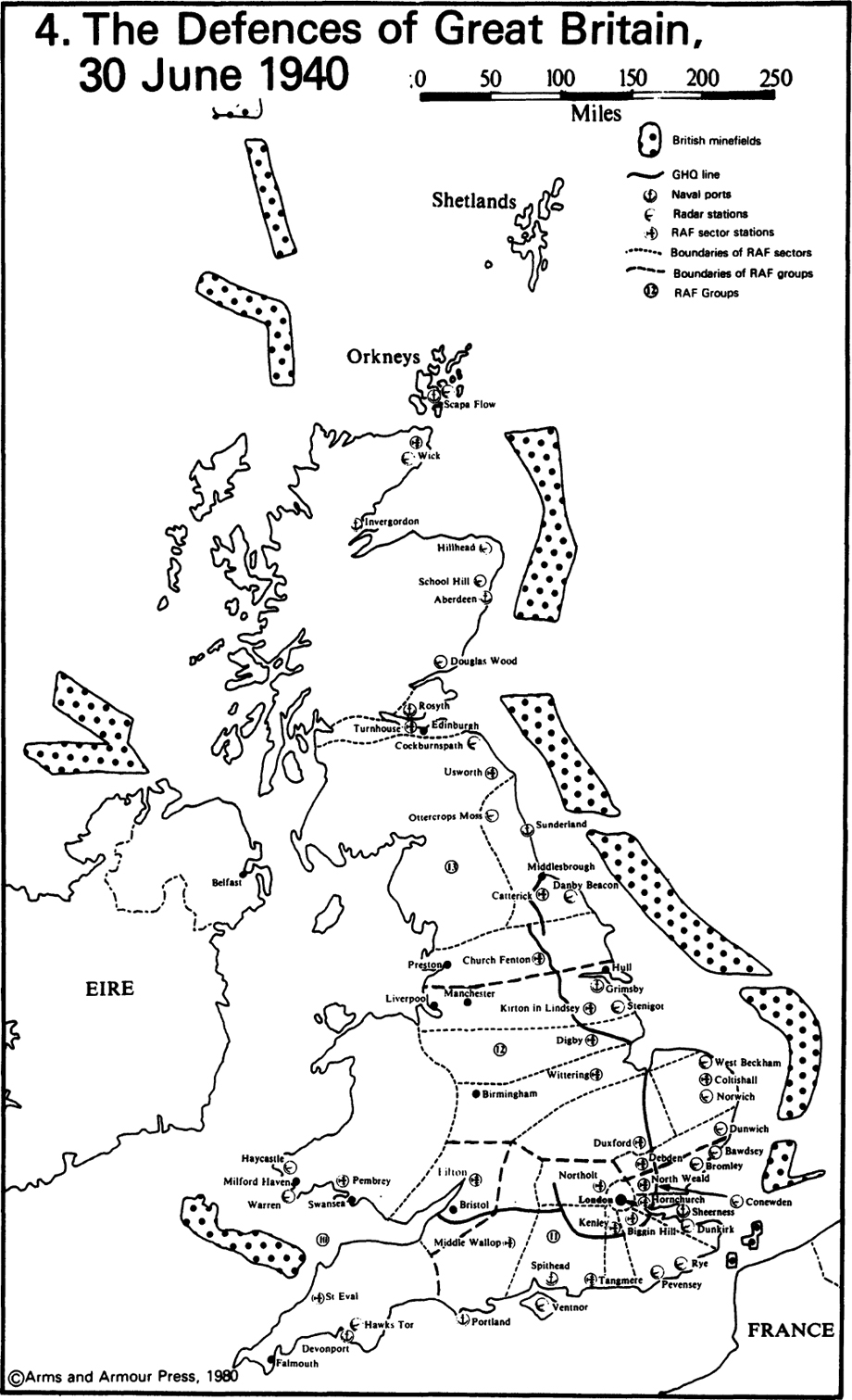

Reports were accumulating of intensive enemy activity in and about the North German and Dutch ports. From neutral sources and travellers leaving Germany, as well as through diplomatic channels, the first hints of the enemy’s intentions began to filter through. As yet, its size, direction and timing were obscure, but from a signal by Kesselring on 24 May, in which he gave his views upon the ‘Lion’ proposals, it seemed possible that an airborne landing might be expected at any moment. But as June went by without clear corroboration, and also without any sign of airborne troops, fears of a parachute attack receeded to be replaced by a firm conviction that a full-scale invasion must be expected in August. British plans to defeat this assault were governed, of course, by the extremely limited resources at their disposal, and the deployment of those resources was guided by the overall military appreciation of where the main enemy blow might fall. In the absence of positive evidence showing the presence of enemy transport aircraft or shipping close to the Channel ports, but in the knowledge that considerable traffic (much of it assumed to be of a commercial nature) was using the German and Dutch ports, the initial conclusions drawn by the Intelligence Staffs adhered to the traditional opinion, which had been revived in the autumn of 1939 (when the chances of an invasion were rumoured), that East Anglia would be the main objective. Even as German preparation became noticeable along the Channel coast, the General Staff Intelligence (X) Branch at GHQ Home Forces noted on 30 June: ‘East Anglia seems most likely because it is further removed from our main fleet base.’5

The overall deployment of naval and army units, therefore, matched this threat, priority being given to the protection of the eastern sector of the country rather than the south-eastern part where the enemy actually intended to make his attempt. Forces had also to be kept in readiness should the Germans try to take over neutral Eire – a nation which steadfastly refused British protection, but one which figured as a target in the German deception plan.

The Navy prepares

The Royal Navy based its first line of defence upon cruisers and destroyers, preferring to retain its battleships and aircraft carriers at a distance in readiness to intervene only if major German units put in an appearance. By 1 July its major units in home waters were deployed as follows:

Distributed around the island while engaged upon the escort of coastal traffic and as mobile vedettes, there also were some 1,100 lightly armed trawlers and small craft which would give warning of an approaching enemy, but make little or no contribution in a fight.

The low proportion of strength allocated to the defence of the Straits of Dover could be attributed not only to the belief that this area seemed less threatened than those to the north, but also to the appreciation that such a narrow stretch of relatively shallow water was highly unsuitable for the manoeuvring of major naval units, besides being well within range of enemy guns and bombers. The minefields which had previously been laid to protect the trade routes to France were now of greater value to the Germans than the British, forming as they did the foundation of the mined corridor they eventually intended to create in those waters. Efforts by British minesweepers to clear the mines were resisted by aircraft and by fire from the Pas de Calais, although the laying of fresh minefields close in shore and the floating of booms across the harbour mouths was completed without delay. Likewise, the reinforcement of the existing coastal batteries defending the ports and the Straits of Dover was soon implemented, but the desire of Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay, the Flag Officer Dover, to instal long-range guns for use against the enemy in France, could not be met immediately. A single 14in naval gun was known to be available and was being made ready.7

The Admiralty’s plan depended upon timely intervention by local naval forces which had been forewarned by early information from regular nightly destroyer, MTB and Coastal Command aircraft patrols watching the enemy ports. It also was hoped to receive warning from ‘Listening craft’ fitted with Asdic, and from an inshore line of drifters and motor boats equipped with radio, flares and rockets. Initially, it was intended that those destroyers closest to a threatened sector would attack at once, in the hope of forestalling a landing. If that failed, a major effort would be postponed until substantial forces of cruisers and destroyers, under the maximum cover from fighter aircraft, could be concentrated. In the most favourable circumstances an interception might be made within a few hours – even, with luck, a few minutes. A strong concentration of cruisers and destroyers from Sheerness and Harwich could deploy in the entrance to the Channel off the North Foreland within two hours, and five hours later these could be reinforced by warships from Hull. Only if the major German units put to sea would the battleships intervene,8 a decision which reflected the reluctance of seamen to manoeuvre big ships in a confined space. In essence, therefore, the Admiralty plan, while hoping for the best, made no guarantee that the enemy would not get ashore unchallenged.

An army at its weakest

Much therefore depended upon the Army, but Home Forces under the command of General Sir Edmund Ironside, though replete in manpower, was desperately short of equipment. Ironside’s first aim, as he saw it in the immediate aftermath of Dunkirk, was ‘to prevent the enemy from running riot and tearing the guts out of the country …’9 His plan, which was designed to fulfill the demands of the Chiefs of Staff, was presented to them on 25 June. It was based on a succession of stop-lines beginning at the coast and covering a so-called GHQ Line of anti-tank obstacles guarding Bristol, the Midlands and London, construction of which had not yet started. Inland, too, lay the armoured and semi-mobile formations upon which everything was staked, to deliver a decisive blow should the enemy obtain a firm purchase ashore. Delay was the best that could be expected at the stop-lines, where most of the 786 field guns were deployed, or at the GHQ Line, where the bulk of the 167 anti-tank guns were to be posted. But the mobile forces were enfeebled, consisting as they did in Lincolnshire of the 2nd Armoured Division (which had but 178 light tanks instead of its entitled number of 213 medium and 108 light tanks), and in Surrey of the 1st Armoured Division (newly returned in disarray from France) with only 9 medium tanks. By the end of June, the latter formation would be raised to 81 mediums and nearly 100 lights and, at the same time, would take under command the 1st Tank Brigade with its 90 heavy Matilda tanks – instead of the 180 its establishment warranted10 – and, at a fraction of its full strength, would become the most powerful striking force in the British Army.

Defence of the south-east of England was the responsibility of XII Corps (Lieutenant-General A. Thorne) and the key sector in Kent where the Germans planned to land was occupied by the 1st (London) Division (Major-General C. F. Liardet). Thorne considered that the landing was more likely to come between the Graveney Marshes and Dover than to the west of Dover. He therefore laid down the Corps Line running from the Marshes to Dover through Canterbury, a system which, for much of its length, followed a railway track and for only a small proportion of that distance could be said to incorporate natural features which provided a significant obstacle. Liardet’s triple intention was to defend the beaches, be prepared to occupy the Corps Line and also to be ready to attack the enemy east or west of the Corps Line. The resources at his disposal he called ‘ludicrous’. 1st (London) Division had been designated as ‘motorized’, a derisory title as it stood at the end of June. Since its mobilization in September 1939, nearly all its vehicles were still those which had been requisitioned from civilian firms. Some of its strange assortment of vans and lorries still bore their original merchants’ names, and its troop transports were civilian coaches which, in happier days, had taken holiday makers to the seaside. In May, its motor-cycle reconnaissance unit had been removed and sent to its doom in the last-ditch defence of Calais, the motor-cycles then being given to 1st Armoured Division.

On 5 July, Headquarters Royal Artillery of 1st (London) Division, under Brigadier J. Price, controlled 34 pieces of field artillery and 12 assorted guns endowed with a speculative anti-tank capability. They were composed and located as follows:

They were short of ammunition, had not fired practice shoots for some time, and had more guns than suitable vehicles to tow them.

As for the infantry, they spent most of their time digging and sandbagging static defences and spent little enough time exercising or firing their weapons, there being a dire shortage of ammunition for the latter purpose. 198th Brigade held the coast line of the Isle of Thanet; Deal Garrison, consisting mainly of 3,000 Marines, were in the line on either side of that port; Dover Garrison, composed of a miscellany of local units, covered the sector between Dover and Folkestone; Shorncliffe Garrison had the stretch of coast from Sandgate to Dymchurch Redoubt; and 135th Brigade (detached from 45th Division) the line from Dymchurch to Midrips. 1st (London) Brigade provided the mobile reserve in the north, while 2nd (London) Brigade lay to the southward, including the task of counter-attacking the airfields at Lympne and Hawkings, which Fighter Command intended to evacuate when enemy pressure became heavy. This deployment, concentrated in the north and diluted in the south, left the door wide open to the Germans’ intended descent. It would be outflanked immediately if the coastal defences fell.

Interwoven with Liardet’s infantry, however, was a fairly formidable array of coastal and anti-aircraft artillery. Two 9.2in guns in the Citadel at Dover could reach half-way across the Channel. Four old 6in guns (with a range of only 12,000 yards) and two batteries of modern 6ins (with a range of 25,000 yards), which had composed the pre-war armament, augmented the defences. To these there were now added, spaced along the coast, a number of Emergency Batteries consisting of 4in and 6in guns (manned by sailors and army gunners) which once had been mounted in ships during the First World War. From improvised emplacements and with 100 rounds each (of which they were told no more was available) they were instructed to fire at ‘big game’, engaging small craft only if they were in large numbers. For night illumination, searchlights were also deployed. Quite the most versatile and modern artillery weapons in the area were those belonging to Major-General F. G. Hyland’s 6th Anti-Aircraft Division, which was responsible for the guns defending the approaches to London, as well as key ports and airfields. In the region of Dover and Folkestone, Hyland had placed 18 of the latest 3.7in guns (which also had a powerful anti-tank capability if the gunners chose to make use of it), plus a few First World War 3in anti-aircraft guns, some modern 40mm Bofors, four 20mm Hispanos and many machine-guns. Normally these guns fired from prepared emplacements, but all were given a secondary, mobile role and were issued with what little anti-tank ammunition was available.

The beach defences, apart from the artillery, amounted to a thin infantry screen, with scarcely any mines and only a few strands of wire to hamper enemy tanks and infantry. Inland, Liardet’s mobile companies and platoons were spread widely at nodal points whence they hoped to mount local counter-attacks against such vital places as the Mansion, Hawkinge and Lympne airfields. Only one battalion (1st London Rifle Brigade) could be spared to counter-attack both Hawkinge and Lympne. The road-blocks, shared with the LDV, merely introduced a check to road movement and a watch over lonely places for paratroops. Armed chiefly with shotguns, trained only in the most rudimentary way and prone to report the slightest unusual occurence as a hostile act, these enthusiastic volunteers made movement by darkness a perilous occupation. On the night of 3/4 June alone, there were four cases of people being shot dead in Britain for allegedly failing to answer a challenge.11

At the root of the British weakness was a dire shortage of weapons and inadequate factory production to make good the deficiencies. Field-gun production ran at about 50 guns a month, infantry and medium tanks at a mere 100.12 If, at the end of May, the Chief of Staff had sombrely to admit that ‘Should the Germans succeed in establishing a force with its vehicles in this country, our armed forces have not got the offensive power to drive it out,’ they were not much better off at the beginning of July. Everything worked on a hand to mouth basis. Improvization was the watchword, training was restricted by lack of ammunition, and hope stood supreme. And just to make matters difficult, the supply services continued to perform their duties at this critical moment as in the manner of peacetime; meticulously they insisted upon requisitions being tendered as ‘by the book’ – either that or the supplies stayed in their depots.14

Air power – the main element of defence

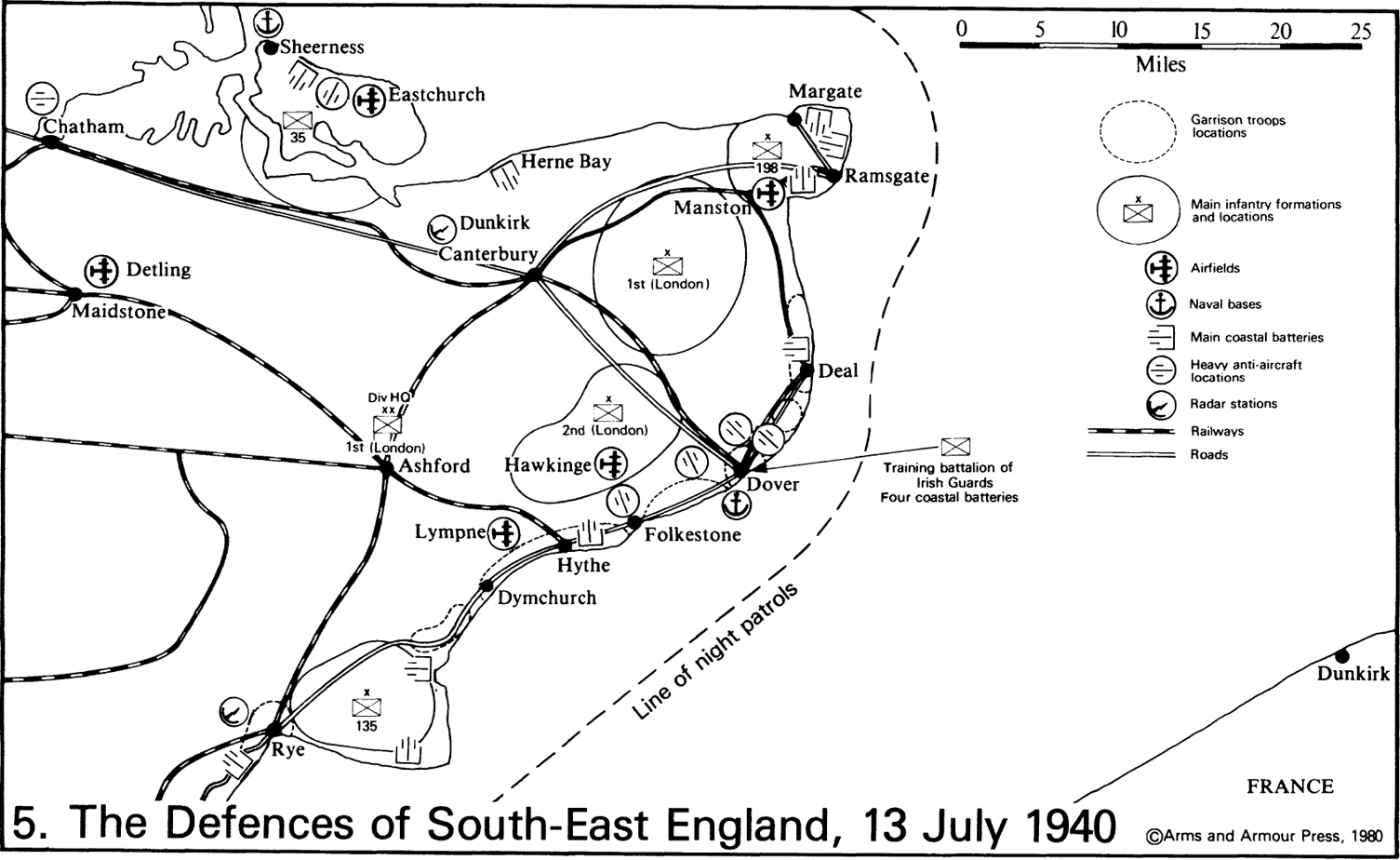

The RAF alone had the weapons and the long-prepared system which offered hope of coping with this unimaginable situation. Since 1915, when enemy aircraft first dropped bombs on Britain, a comprehensive organization of command and control had evolved, in which observation posts, manned by the Observer Corps, and linked by land-line and radio to communication centres, provided the vital information upon which the fighter and antiaircraft forces depended for exerting the maximum economic influence. Moreover, since the Luftwaffe was first formed, radio interception stations had monitored and assessed the profusion of signals sent by its aircrew under training and, latterly, on operations. Not only was detailed information of its Order of Battle known, but its operational procedures were also understood and it was often possible to obtain warning of raids by listening-in to the aircraft frequencies. Furthermore, since 1938, the observation posts had been powerfully supplemented by the installation of primitive radar locating equipment (called Chain Home (CH) sets) which, although having a 300 per cent factor of inaccuracy, could at least give warning of the approach of aircraft flying above 3,000 feet from a range of about 150 miles. The gap beneath that altitude had to be closed by ground observers, since the latest beam type CHL (Chain Home Low) sets had not yet been installed and the first was not expected to be ready until about the end of July.15 RAF Fighter Command, under Air Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, had its headquarters at Stanmore in north London and controlled four Fighter Groups, the Observer Corps, the Radar Group and Balloon Command (which flew barrage balloons over important targets to deter low-flying aircraft), while exercising operational control over Anti-Aircraft Command (Lieutenant-General F. Pile). Under each Fighter Group were the Sectors controlling, by radio, the movements of aircraft operating from airfields within the Sector, each Sector Control being located at one of the airfields. To the largest Group, No 11 (Air Vice-Marshal K. R. Park), fell the task of defending south-east England; on 18 June, its seven Sectors controlled between them some 36 twin-engined Blenheim fighters (with but a limited combat worthiness) and rather fewer than 200 Spitfire and Hurricane, single-engined fighters. On his western flank lay No 10 Group and to the north No 12 Group, each of which, if time and circumstances allowed, could send fighters to his assistance. In the extreme north, No 13 Group looked after the rest of England, Scotland and Northern Ireland. All the Groups and several of the fighter squadrons were below strength in men and machines, as well as in spare parts. On 4 June, there were only 36 Spitfires and Hurricanes ready for issue from the Aircraft Storage Units. But production of fighters, in response to stirring exhortations from Churchill and the drive of Lord Beaverbrook, the recently appointed Minister of Aircraft Production, had risen sharply. It had been 265 in April, 325 in May and in June it was to be 446,16 a contribution which largely restored the losses of May, but which threatened to be wasted due to an acute scarcity of trained pilots. In relation to an authorized establishment of 1,450 pilots, Fighter Command could call on fewer than 1,200 in mid June (although some 60 were about to be transferred from other commands)17 while only some six a day were coming from the training units.

The system of radio control, linked to radar early-warning, offered substantial economies to set against the heavy German advantage in numbers, and the Germans themselves had been made aware of the technical qualities of the Spitfires during the fighting over Dunkirk. In addition, they were impressed by the evidence of the RAF’s radio command and control of fighters in combat, and of the radar chain which they discovered as soon as they had set up monitoring equipment near Calais in May. It was a shock to find that the British were so far ahead of them. They had nothing so good as the radio system and their radar was inferior to that of the British. The best contribution they could apply to the electronic warfare of the day was a single Freya radar station at Wissant, to locate British convoys as they sailed to and fro in the Channel.

As for the British bombers’ capacity, they suffered by day, as did the Germans, from the serious risk of operating without escort, and a chronic inability to find and hit targets by night, unless these were within short range and well defined on the ground. In the event of imminent invasion it was intended that RAF Bomber Command concentrate on enemy shipping in ports and in transit. For the time being, priority was given to attacks on the German aircraft industry and airfields Throughout June, Wellington, Hampden, Whitley and Blenheim aircraft roamed across the occupied territories and over West Germany, scattering bombs without doing the slightest damage worthy of the effort. It had not yet been realized that dead reckoning and astral navigation were completely ineffective under wartime conditions, and the British, who had found it hard to believe that the Germans possessed an accurate beam navigation system, naturally did not have one of their own.

If everything would depend upon Fighter Command in the air, this was not to say that Dowding was worried only about that dimension. He was concerned, too, about the vulnerability of his airfields, which were quite inadequately defended by anti-aircraft guns and, in many instances, almost unprotected by troops. In a few places, Local Defence Volunteers were incorporated into the perimeter defences, but for the most part, since the Army was principally engaged in developing its lines of static defence, RAF ground staff had to be given arms (when they were available) in the hope that they would make a stand if the enemy arrived. At the best, however, only rifles and a few machine-guns comprised the defence of the airfields, even of those closest to the coast.18

The people at war

Fully occupied in dealing with a mammoth task, the fighting Services had little time to consider the nation’s plight. Factory workers, too, engaged in a twelve hour, seven day week, enjoyed few moments for contemplation, while an army of helpers in other kinds of work came home at the end of the day to go on patrol with the LDV, stand watch with the ARP, the AFS (Auxilliary Fire Service) or the Police Reserve, drive ambulances and attend for duty with the WVS (Women’s Voluntary Service) or the First Aid workers, or serve in any one of a hundred different occupations. With the Home Office at the centre, but with tentacles out to the other Ministries such as Transport, Health, Food, Works, Labour and Pensions, the civil defence of the nation rested upon the traditional committee system functioning through massed voluntary service controlled by a relatively small core of paid, fulltime officials. But an ARP Controller, upon whom the welfare of a large district might depend, was often a town clerk, whose training in emergency work was minimal and whose psychological attitude and that of his staff was far removed from the demands of quick, militaristic decision making. A Chief Constable might sometimes control the ARP, but he was not necessarily in tune with local government departments whose methods tended to differ from his more authoritarian approach. An ARP Post might be manned by a full-time Head Warden whose job it would be to recruit, train and direct the volunteer wardens and messengers within his boundaries. Before the collapse of France, it had been difficult to recruit sufficient manpower; afterwards, and as Kesselring’s bombers droned overhead, volunteers flocked in and could only be given rudimentary training within the few days available. Every one felt the need to become involved and a great many of the most patriotic appointed themselves as personal guardians of the nation’s security, with the result that the slightest suspicious act, such as flashing a light in the blackout or speaking with a mildly foreign accent, could lead to rumours and reports of the presence of the dreaded Fifth Column.19 On 31 May, when the signposts were being removed in order to hamper parachutists in finding their way about, Vice-Admiral Ramsay, deeply involved as he was with the evacuation from Dunkirk, had received a sufficient number of alarmist reports as to cause him to inform the Admiralty of numerous acts of sabotage in the Dover area such as communication leakages, fixed defence sabotage, and second-hand cars purchased at high prices and left parked at convenient places – none of which could be substantiated.20

No one could be sure how the undisciplined civilians would behave when confronted with the terror of bombing and by the appearance of a hostile army on English soil for the first time in many centuries. Because refugees had blocked the roads and delayed the movement of troops in France, strict orders were issued for the British not to leave their homes but to ‘stay put’. Yet already the early minor air raids of June had caused ripples of movement among distraught people. Since it was so difficult to know how well the untested professional RAF defences would work, no one could be sure what would happen with a ramshackle voluntary one. It was by no means certain if communications or the distribution of food could be maintained. Starvation or a breakdown in the health services might rapidly cripple the closely packed cities. As it was, industrial production was being affected already by the nightly air raids, and the deficiencies of some local councils under stress and strain were being exposed. But when, on 19 June, the Chiefs of Staff recommended a large transfer of civil control to the eleven Regional Commissioners (who had been appointed at the outbreak of war to ensure the smoother running of the administrative machine during abnormal conditions) the Cabinet declined to approve.21 Hesitating to alarm the population and anxious not to upset the elected hierarchy, the Cabinet took the risk of a breakdown by permitting the existing, complex local government arrangements to continue.

The first test would come when Kesselring’s exploratory operations would give way, on the 19th, to large formations arriving in daylight.