DAYS OF THE EAGLE

The Battle of Britain opens – 8 July

Notwithstanding the confidence with which Goering spoke at the meeting in Berlin on 8 July, when the decision to go ahead with ‘Sealion’ was taken, he was aware of misgivings among his subordinates grappling with the British over southern England. A night bombardment of the invasion ports by the Royal Navy had taken place which neither the Luftwaffe, nor the Kriegsmarine nor the coastal batteries had been able to prevent. Then there had been a shocking incident at dawn on the 7th when RAF Blenheims from Bomber Command had struck by surprise at Haamstede airfield catching a Staffel of Messerschmitt 109s as they were taxiing out to ‘scramble’ to their own defence. Seven aircraft were destroyed or seriously damaged, three pilots killed and three wounded, resulting in this unit being withdrawn from operations.1 The previous evening, Kesselring and his senior commanders had studied the latest combat reports and found that, not only was enemy resistance well sustained, but it was enhanced by an improved percentage of interceptions. German formations were being tackled well out to sea and this, Martini, the Head of Luftwaffe Signals, attributed to radar detection. Most of the radar stations had been plotted by his direction-finders and by photographs, so he now pleaded that they should be destroyed. Already Jeschonnek had authorized Kesselring to do this when he was ready.2 Now it was decided to attack them on 8 July, the day before ‘Eagle Day’ which, it was expected, would be the 9th.

Intensive reconnaissance activity throughout the 7th and 8th was, in itself, fair warning of the approaching climax; 200 sorties were flown by the Luftwaffe over southern and eastern England, intermingled with widespread bombing and strafing throughout the hours of daylight.3 Of prime importance were the strikes at 0900 hours on the 8th, against the CH radar stations at Conewden, Dunkirk (near Sheerness), Rye and Pevensey, by the élite Operational Proving Unit 210, which specialized with its Me 109s and 110s in hitting pin-point targets. Each attack, taking the defenders by surprise and meeting no opposition, was delivered with extreme accuracy so that, for the time being, only Dunkirk stayed on the air. Likewise, an attack against Ventnor station a few hours later by Ju 88s put it off the air for the next three days. Within a few hours, some of the stations were back on the air,4 but holes had been punched in the British Early Warning System, and these Kesselring and Sperrle exploited. Covered by free-chase missions, waves of German high-level and dive-bombers launched heavy raids on shipping in the Thames estuary, off Portsmouth and near Portland. Simultaneously, low-level attacks against Lympne and Hawkings airfields by Ju 88s, which arrived totally undetected (as they would have done whatever the state of the CH radar), carpetted both airfields with bombs, destroying buildings as well as several aircraft within the hangars. For a time both airfields were out of action and the bomb craters, even when filled in, thereafter continued to make operations from the grass strips hazardous. But these attacks, devastating as they were, bore only slight comparison with the one against Mansion three hours later. This was led at low level by Operational Proving Unit 210, backed up at high level by Do 17s, and caught several fighters on the ground or about to take off. By a miracle only one Blenheim night fighter was destroyed and a few Spitfires slightly damaged, but the harm to ground installations and the morale of the station personnel could not be dismissed as an irrelevance. Both would suffer again and again as, in the days to come, attack followed attack. The fact remained that, for the remainder of the 8th and part, too, of 9 July,, these three coastal stations were entirely or partially out of service.

The German High Command in debate. Standing, left to right: Jodl, von Brauchitsch, Raeder and Keitel; seated, back to camera: Goering, Hitler. (Author’s collection)

A typical Chain Home radar station to detect aircraft at long range. The tall towers are the transmitters; the smaller ones are the receivers. (Imperial War Museum).

An Englishman’s idea of invasion, June 1940, as shown in Picture Post. A highly optimistic solution, this was unlikely to work.

General Sir Edmund Ironside, Commander-in-Chief of the British Home Forces. (Illustrated)

Sir Dudley Pound, the British First Sea Lord. (Illustrated)

Air Marshal Sir Cyril Newall, British Chief of the Air Staff. (Illustrated)

Air Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, commanding RAF Fighter Command. (Illustrated)

Winston Churchill inspects some rudimentary defences. (Imperial War Museum)

A British 3-inch anti-aircraft gun on a First World War chassis in London. Mostly of use only against low-flying aircraft, their noise did help to stiffen civilian morale. (Ian V. Hogg)

Kesselring directing his air fleet from his ‘Holy Mountain’ at the Pas de Calais. (Kesselring)

A 9.2-inch gun of the Citadel Battery, Dover. It gave little protection to its crew. (Ian V. Hogg)

A typical emergency beach battery — 4-inch gun with only 100 rounds per gun. (Ian V. Hogg).

A 6-inch gun of the Langdon Battery, Dover — a first objective for the German glider troops. (Ian V. Hogg).

The cliffs at Dover, from a contemporary German military topographical guide to England, Bildheft England insgesamt. (Lionel Leventhal Collection).

A German 28cm long-range gun, capable of harassing British convoys and giving support to the landings. (Ian V. Hogg)

Folkestone under fire.

The air fighting of the 8th also produced its heavy toll of casualties to aircraft (destroved and damaged) and to aircrew:5

|

RAF |

Luftwaffe |

Fighters |

31, 19 pilots |

27, 18 pilots killed, |

|

wounded or missing |

wounded or missing |

Bombers |

16 |

21 |

This rate was proportionately entirely in the German favour, although there was disquiet when it was reported by Martini that the British radar was once more transmitting. Quite wrongly it was concluded that installations such as these could not easily be knocked out, and so they were omitted from the list of targets prepared for the 9th – ‘Eagle Day’ – a bizarre omission when it is remembered how important these installations were to the efficiency of Fighter Command. Indeed, the entire German plan for what was intended, after all, as a stunning blow to the RAF, contained irrelevant objectives. For one thing, although airfields were principal targets, those attacked, with two exceptions, were not those directly connected with fighter operations: this could be put down to faulty Intelligence. For another, there was no immediate attempt to follow up the successful attacks on Lympne, Hawkinge and Mansion, all three of which were important because they belonged to Fighter Command. And there was a facile diversion of effort permitted in that dockyards were left on the target list, admittedly as secondary targets.

Eagle Day – 9 July

In variable visibility, which worsened as cloud built up throughout the morning, the first free-chase German fighter missions of the day preceeded the appearance on Fighter Command’s plotting boards of three distinct masses of enemy aircraft. The plots on Park’s left flank were seen to be approaching as if to strike east Kent, but continued towards London up the Thames estuary. The centre block came in over Bognor and, for a moment, it was feared that the fighter station at Tangmere would be the target; instead these aircraft too moved inland, making, in fact, for RAF Station Odiham (an Army Co-operation field) and the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough. Meanwhile, off Portland, the plots resolved themselves into a Kampfgeschwader (KG) of Stukas with the aim of attacking shipping and acting as a diversion from the other raids.

Only the attack in the east made a pronounced impression. 74 Do 17s from KG 2 met weak fighter opposition as they skilfully wove through the deepening clouds to their target at Eastchurch airfield. Their bombs landed squarely on target and caused extensive damage to the operations block, the hangars and the ammunition stores, besides destroying a Spitfire and five Blenheims. For the rest of the day this airfield, used by two fighter squadrons, was out of action. Sheerness was also hit and some small ships damaged, but the detached portion of KG 2 which was responsible had parted from its fighter escort so that, when caught by RAF fighters, it lost five Do 17s with an equal number damaged. Elsewhere, the fighting and the bombing became scattered. A few Ju 88s from KG54 broke through to Odiham without doing much harm and they, in retreat, dropped bombs all over the place including a few on Tangmere airfield. Off Portland, the Stukas damaged an escort vessel and sank a trawler, but fled with Spitfires and Hurricanes in hot pursuit.6

In better weather after lunch, the Luftwaffe’s performance looked more impressive. Over 250 Ju 87s and 88s, along with Me 109s and 110s, approached from Cherbourg with the intention of bombing Middle Wallop (a Sector Station), Andover and Warmwell airfields. Detected early and intercepted with commendable precision, only a few raiders found their target and the Messerschmitts were caught at a disadvantage by the RAF fighters. Bombers suffered badly and the German fighters failed to score many kills themselves as they fled. However, a swarm of German bombers broke through to their secondary target, Southampton, and extensively damaged the port and some factories as they roared over the Solent. Yet they might have done better, for they passed by the most important target of all in that area, their Intelligence officers being completely oblivious to the fact that the large factory of Supermarine was engaged in the manufacture of Spitfires.

More effective in maintenance of the aim in the crucial fighter war, were the attacks by Luftflotte 2 against Rochford and Detling (Coastal Command) airfields. Although only a handful of bombers found the former, they caused considerable damage to installations and runways, while Detling caught the full blast of a hail of bombs from Ju 87s which hit the station’s messes when airmen were going to the evening meal, destroyed 22 aircraft – all of which had an anti-invasion role – demolished all the hangars and cratered the runways.

‘Eagle Day’ had fallen far short of its high-sounding title and grandiose aims. Instead of stunning Fighter Command by strokes to the heart and brain, it had hacked at limbs and sometimes missed even them. Fighter airfields and radar installations had been given time to recover. Command of the German formations had been too flaccid with the result that, confronted by opposition, there had been a marked tendency to head for secondary targets instead of persevering with the destruction of the key, primary ones. At the same time, Fighter Command was dissatisfied that several large enemy formations had wandered as they chose without being brought to battle. And if the results of combats, when they took place, were favourable, it could not be said that the scores for the day taken as a whole were anything upon which to be congratulated, as the following table of fighter and bomber losses amply illustrates:

RAF |

Luftwaffe |

|

Fighters |

26, 10 pilots killed, wounded or missing |

33, 17 pilots killed, wounded or missing |

Bombers |

45, including those on the ground |

40 |

The RAF bomber losses, so rarely mentioned in üritisn accounts of the Battle for Britain (which tend to speak only of their fighter losses while boasting of the number of German bombers destroyed), were heightened by a disastrous daylight attack by 12 Blenheims on Stavanger airfield against a reported heavy concentration of enemy aircraft. Instructed to abandon the mission if cloud cover fell below 70 per cent, they continued in clear skies and were pursued by Messerschmitts on their way home (having, as at Haamstede on the 7th, caught the Germans by surprise). Eight bombers failed to return and the other four were badly damaged.8 In expenditure of aircraft both sides were exceeding rates of replacements, but the German reserves seemed likely to out-last those of the British; in the matter of reserve air crew, however, the Germans had no worries while the British were hard-pressed, their replacements being quite inadequate to restock a meagre pool. For these reasons, if no others, Dowding awaited the next day’s fighting in trepidation.

The second day – 10 July

To his surprise the Luftwaffe did not resume its massed tactics on the 10th. Instead it indulged in repeated raids against airfields and communication centres by several small formations, covered by fighter sweeps. They gave the Controllers little trouble; with plenty in hand they were able to gear their response in appropriate strength to a nuisance. Lacking concentration, the Germans forfeited the defensive powers inherent in large formations. These tactics, which had proved efficacious in France, once the main opposition had dwindled, were the products of German miscalculation allied to the British failure on the 9th to press home their interceptions, added to the exaggerated claims of 80 British aircraft shot down and to misreading of the damage to targets.

Nevertheless, surprise attacks by small, well-led formations did inflict damage out of all proportion to the effort employed – as Mansion discovered when Operational Proving Unit 210 visited it again and left hangars, dispersal areas and three Blenheim night fighters in ruins, for the loss of two Me 110s shot down by ground fire.9 On the other hand, three He 111s which penetrated well into the Midlands to bomb the fighter Maintenance Unit at Colerne, missed the numerous Hurricanes parked on the airfield. Nowhere was the damage so bad as at Mansion, but Middle Wallop, Tangmere, Hawkinge, Eastchurch and Hornchurch each received their small ration of bombs, and on each there was damage and temporary disruption which was sufficient to increase the strain on Fighter Command. At the end of the day, the commanders of both sides had good reasons to reconsider their position, although the relatively light casualities (compared to the previous day) gave no indication that a turning-point had been reached.

|

RAF |

Luftwaffe |

Fighters |

17 (6 on ground), 4 pilots killed or wounded |

10, 7 pilots killed or wounded |

Bombers |

12 (6 on ground) |

17 |

The third day – 11 July

Dowding sensed that there was a serious change impending. Those Luftwaffe orders which were read by Ultra told him that a massive operation was in preparation for the next day, 11 July, one which would cross the English coastline at many points between Newcastle-on-Tyne and Exeter. He therefore chose this moment when, in his estimation and that of Park, certain squadrons in 11 Group were exhausted, to bring south some fresh squadrons to replace the tired units. The wisdom of this move is open to criticism, because many of the veteran pilots withdrawn were hardly more weary than their opponents, and those who survived had become, within a few weeks, deadly killers in air combat. And veterans, as might have been discerned by examination of combat results, were almost the only pilots who shot down opponents in any numbers: about 90 per cent of all kills were, in fact, scored by only 10 per cent of the pilots engaged, and many ‘green’ pilots never or rarely fired their guns in action. But Dowding’s front-line strength wore a sickly look. 11 Group still could not put more than 200 Spitfires and Hurricanes in the air to meet formations which could be three times that number, and the luxury of drawing upon a reserve from neighbouring Groups was frequently denied it, either because those Groups were themselves involved on their own front or because there was insufficient time in a fast moving battle.

Despite the optimism of their Intelligence officers, the Germans were none too pleased either. It was obvious to the pilots that the enemy resistance was as hard as ever, and to their leaders that their blows were not reaching the essential targets to help win air superiority before S Day – which was only three days away. As yet, the surface forces of the Wehrmacht could be guaranteed neither the immunity from air attack they demanded nor the bombing support they desired. With these things in mind, Goering issued trenchant orders that, on the 11th and 12th, it was the enemy airfields which were to be saturated, without the softer option of dropping bombs on secondary targets. Two days had been wasted and they would be hard-pressed to be ready on the evening of the 13th to commence the softening-up of the designated beachhead in readiness for the landing next day. At the same time, Goering called a conference for the 11th at Kesselring’s headquarters in Brussels, with a view to thrashing out tighter procedures and making better use of resources. Rather late in the day it was appreciated that techniques which had stood the Luftwaffe well against the weaker forces of Poland, Norway, Holland, Belgium and France, were unsuitable against a maritime power such as Britain. There was even doubt in Goering’s mind whether it was wise to continue with ‘Sealion’ at present – but this attack of cold feet he kept to himself, particularly since it contradicted the resounding claims he was retailing to the outside world about the victories his airmen were winning over England.

For the British, the 11th was climactic. During the night, He 111s had roved purposefully inland, finding their targets accurately by the use of ‘Knickebein’, lowering industrial production by their mere presence and keeping people awake. And the targets they managed to hit in the Midlands were the ones connected with the aircraft industry they sought – the Nuffield Spitfire factory at Castle Bromwich and the Bristol Aeroplane Works at Filton. It was discouraging, too, that the customary early morning enemy reconnaissance missions came and went without loss, and that several small formations of Ju 88s, which swept in low, took coastal airfields totally by surprise. Mansion, Hawkinge, Lympne, Tangmere, Warmwell and Exeter all had visitors and, in varying degree, emerged with their efficiency impaired. Quite apart from the wrecking of support and maintenance services, the early morning cratering of the grass hindered operations by the fighters when they arrived later in the day. This was but the overture to the really heavy attacks which came in mid-morning against selected coastal airfields which, in their turn, would be leap-frogged when attacks were made later against inland fighter airfields. Well supplied by now with detailed knowledge of the area of fire of the defending AA guns, Ju 87s, protected by a top-cover of Me 109s, flew past Dover from the east, before turning west to dive on Hawkinge and Lympne, while Me 110s carried out yet another low-level strafing of Mansion. Fortunately for the RAF, only a few Spitfires were on the ground at Mansion while fighters from the other airfields were already aloft. But again the damage and cratering was heavy and once more the bombers got in and out without suffering badly, the waiting Me 109s dropping on the British fighters as they moved in to attack the bombers. Most serious of all – and quite by chance – one bomb severed the main power cable supplying the radar station at Rye, with the result that this set was off the air for the rest of the day, tearing an even wider gap in the early warning chain, situated as it was on the flank of Ventnor which was still out of action. For the next few hours, indeed, most of the south coast was bereft of its early warning facilities.

British Aircraft Involved

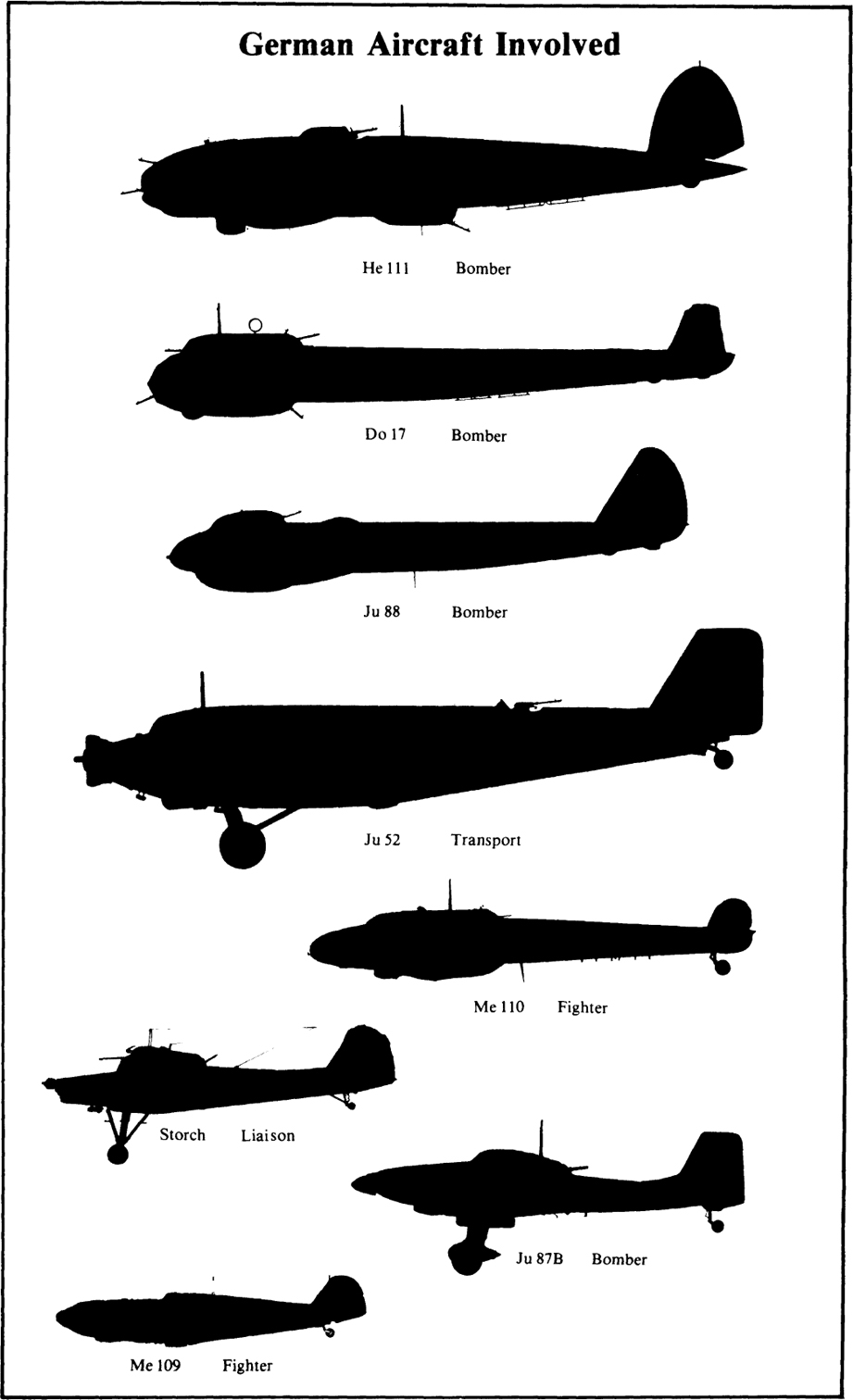

German Aircraft Involved

Dowding’s attention was now attracted northward as the long expected attack from Scandinavia appeared on the plotting tables. Goering, encouraged by Intelligence Branch estimates that only 300 fighters remained to the RAF and that these had all been moved to the south, had authorized a two-pronged raid on northeast England; one by 65 Heinkels, escorted by 35 Me 110s, the other by unescorted Ju 88s. Their targets were airfields. With sufficient radar warning of the approaching raids (but not the slightest help from Ultra), five squadrons of fighters from 13 Group found it easy to intercept the Heinkel group far out to sea, to defeat their escort and treat the bomber formations so roughly that they jettisoned their bombs without hitting a single worthwhile target. Without loss, the RAF destroyed fifteen German aircraft here, and were no less successful against the Junkers 88s to the southward, shooting down ten of the fifty raiders which, nevertheless, pressed home their attack with great courage to hit the airfield at Driffield near Hull where they destroyed ten Whitley bombers on the ground, besides wrecking hangars and administrative buildings. Heavy though the German losses were and discouraging as was the impact of the British resistance to the Luftwaffe commanders and crews (who were beginning to wonder if it were possible to defeat the RAF) the outcome of this attack was by no means entirely in the British favour. Its launching re-emphasized to Dowding the need to retain a strong presence in the north, and the losses it inflicted on Bomber Command were blows against the anti-invasion force. Furthermore, it kept Fighter Command at full stretch on a day when it was completely denied respite elsewhere.

No sooner were the heavy morning raids on the coastal airfields over than, once more, Ju 88s and Me 110 bombers were skimming at low level across the Channel in an endeavour to catch Spitfires and Hurricanes engaged in refuelling on the ground. They were unlucky at Mansion and Lympne, but at Hawkinge and Warmwell managed to shoot up and bomb the dispersal points, bringing about the loss of six fighters and such important pieces of equipment as bowsers. Naturally enough, the morale of the ground crews began to sag and, inevitably, aircraft maintenance became more difficult so that serviceability rates fell into decline. Squadrons in 11 Group which, in the opening stages of the battle had gone aloft with 12 aircraft, now did well to raise 10, and had on strength only an average of 16 pilots instead of 19 as before. But so long as the inland Sector Stations, which carried out the bulk of the routine servicing at nights, remained intact there was little fear of a general collapse, and 12 Group’s squadrons, by comparison with those of 11, remained fresh and strong.

Spending the afternoon recovering from their morning efforts, Luftflotten 2 and 3 gathered for a maximum effort in the evening, in the meantime keeping the RAF pilots in a state of tension by random fighter sweeps and hit and run raids shortly before tea-time. A singularly successful operation by Operational Proving Unit 210 ravaged the buildings of RAF Martlesham; while destroying only one bomber on the ground, it came and went without loss, put the airfield out of action for two days, and its Me 109s shot down three fighters in combat. It was teams of weary RAF fighter pilots who came to Readiness and were successively scrambled to meet the enormous evening raid which began to build up over France and Belgium at about 1700 hours, spotted only fragmentarily by the surviving Hawks Tor and Dunkirk radar stations.

The assault was phased to begin in the west, where Sperrle sent his dive-bombers against Portland as a feint, and then rise to a climax as successive waves of aircraft roared inland to strike at Worthy Down, Middle Wallop, and, a few minutes later (when it was hoped that the mass of RAF fighters would be drawn to the west), over East Kent to strike at Redhill, Biggin Hill, Kenley, Eastchurch and Rochester. This was intended by the Germans as a master-stroke. Inevitably a considerable number of RAF squadrons were sent to deal with the initial attacks in the west, while inadequate early warning denied Park sufficient information of the main attack due to fall on his left flank. Dowding could take comfort from the fact that the feint attacks were expensive to his enemy and did only light damage to their targets, but his paucity of numbers was made all too plain when the mighty German attack in the east broke through all along the line. Between 1830 and 1930 hours the skies above Kent, Sussex and Surrey were tormented by combat as the German formations rolled in. The fact that they often missed their way and hit the wrong airfields was incidental. Eastchurch and West Mailing (instead of Biggin Hill as intended) each received a pounding, along with Rochester, where the Short factory which was building the new generation of four-engined Stirling bombers, was hard hit. Croydon too (instead of Kenley as intended) was plastered by Operational Proving Unit 210, with no harm to the fighter squadrons there, but severe damage to factories making aircraft and repairing Hurricanes: the one redeeming feature was that this élite unit was caught on the way out by defending fighters and severely mauled with the loss of seven machines, including that of its redoubtable leader. But the freechase fighters which covered the entire operation caught the struggling and out-numbered RAF fighters at a disadvantage in the raid’s aftermath, and completed their task by indulging in low strafing of all manner of targets on their way home. To rub it in, as the day drew to its painful close, the coastal fields of Hawkinge and Lympne were once more attacked while, as of routine, the minelayers took off after dark to pursue their deadly sowing on the flanks of the intended invasion area. Next morning the troops would begin to embark for the great adventure.

Casualties for the 11th had been by far the highest yet in the air battle over Britain.

|

RAF |

Luftwaffe |

Fighters |

47, including 8 on the ground, 28 pilots killed or wounded |

36, 12 pilots killed or wounded |

Bombers |

15, including 11 on the ground |

54 |

Disquieting as these losses were to the Luftwaffe’s bomber units (such a high proportion of which had been sacrificed in the ill-conceived foray across the North Sea), they were quite as disturbing to Dowding. It would have looked even worse if he had known that only nine Me 109s had gone down and that the bulk of the enemy fighter losses were among the more vulnerable Me 110s. As it was, he could ruefully reflect that the 28 fighter pilots lost to him represented about 30 per cent of his reserve of these priceless young men, whose powers of resistance were being ruthlessly sapped and who, in their sacrificial attempts to kill bombers, were losing ground to the German fighter arm. At this time, an average of only six pilots per day were rated fit for introduction to action11 – a figure far below that available to the Germans. The state of mind among Fighter Command pilots may, perhaps, be summedup by this extract from a letter written by one of them before he turned in to snatch a few hours disturbed sleep that night:

‘I never believed that the day would come when the need for sleep became so overwhelming and the chances of getting it less likely. The squadron has been airborne five times to-day and on two of those occasions fully engaged. We have lost three pilots and four aeroplanes and, for all the wonderful claims of nearly 200 enemy aircraft shot down, it seems to make no difference. Still they come on and everywhere you turn there is a Messerschmitt above. And we have been lucky. So far they have left our airfield alone. How long can this go on? How much more weary can one become? And when do we become so tired that it is no longer possible to fly with any chance of doing the right thing or of shooting straight if one is fortunate enough to get the enemy in one’s sights? And how long will it be before the enemy or just plain error makes an end to it all?’

The pilot concerned was one of those who, a few days later, died in flames.

The set-back

These ugly facts about the situation were to be driven home to the British next day, the 12th, when the Luftwaffe returned to the charge, sent in by leaders whose motivations bordered on desperation. This had to be the master-stroke if they were to be able to support the surface forces in their landings on the Kent coast. But as the assault was renewed with unrelenting fury and evidence of success began to reach the German commanders, disquieting news of another kind filtered its way back to OKW, where the confirmation of the 13th as S Day was pending. Reports from the meteorological offices told of ‘fronts’ moving in from the Atlantic, with the promise of lower visibility, rain and stiff breezes rising to a peak in the early hours of the 13th – the very moment when both the airborne and seaborne troops would be approaching their dropping and landing zones.

Once more Hitler listened to his Service Chiefs giving their estimates of the latest position on the Channel coast. The Army, said von Brauchitsch with pride, was ready. The Kriegsmarine, reported Raeder, was as ready as ever it was likely to be in the circumstances, but an operation which already hung on the lip of disaster, due to the narrow margins of error upon which it was founded, must fail if adverse weather ruffled the Channel while the small craft were at sea. With all the persuasion at his disposal he counselled delay – by only 24 hours, perhaps, and especially since calmer weather was predicted after midday on the 13th. He remarked afterwards to Schniewind that he had not expected to have his way, for Hitler’s mood looked forbidding. But he was saved – very much to his surprise – by Goering. Prior to the meeting, the Feldmarschall had listened sympathetically to Jeschonnek’s interpretation of the weather forecast and he had agreed that, in marginal conditions such as those to be expected, the airborne troops might be scattered and be unable to find their objectives – let alone capture them. He had spoken on the telephone, to Kesselring, and from him gathered that another 24 hours grace to enable the Luftwaffe to exploit its successes of the previous day, and subsequently pay much closer attention to targets in the invasion area, would be more than welcome. Kesselring stated, in fact, that he would have asked, in any case, for a postponement. The poor results achieved on ‘Eagle Day’ itself had set the programme back by at least 24 hours – as already he had warned Goering on 10 July. So Goering sided with Raeder and, requested that S Day be postponed until the 14th.

Hitler was impressed. He asked Jodi what might be the consequences of a delay and received from Jodi’s deputy, Warlimont (who had planned the invasion’s schedule),12 a detailed explanation. The immediate effect would be to halt embarkation, with a possible forfeiture of security and the further exposure of men and ships to enemy bombing. Apart from that, Warlimont declared, a postponement by one day might prove advantageous on the beaches. On the 14th, as opposed to the present date of the 13th, the troops, by coming ashore shortly after first light to allow time for the airborne operation to take effect, would arrive 1 1/2 hours before high tide, when the tidal streams were at their weakest (about 1 knot) and seamanship, therefore, least under strain. It would mean the soldiers would have to cross a slightly longer stretch of beach, but this might not be so prohibitive as it sounded since the beach, particularly at Hythe, was steep and the distance involved short.

As was to be expected, von Brauchitsch expressed doubts; he had no desire to expose his soldiers to aimed fire at the water’s edge for any longer than necessary. Raeder, on the other hand, concurred with Warlimont and took the opportunity to congratulate the soldier on his grasp of a sailor’s problems.

‘Then,’ announced Hitler, ‘S Day is set back for 24 hours and will take place to the original timetable on the 14th – dependent, that is, upon a favourable weather forecast being presented to us at this time tomorrow.’

Nobody, it seems, asked what might happen if the outlook still appeared unfavourable.

The fourth day – 12 July

One consequence of postponement which Warlimont had not foreseen when he gave his assessment, was the flurry of radio signals generated by the imperative need to tell lower formations of the change in timing. There was scarcely an out-station which did not need to know. And so, throughout the morning of the 12th, British interception services became aware of a dramatic increase in traffic and a certain repetition in the style of messages being passed. Ultra translations also began to reveal phrases and codewords which, until then, had been unheard or rare. When combined with a study of the latest air photographs, which showed small but significant changes in the position of craft in the Invasion Ports, and linked to the mounting violence of the air offensive, the likelihood of an imminent invasion became even more pronounced to the Chiefs of Staff. At midday, as the Luftwaffe was bending all its efforts to attack England, three special and highly perilous flights were made in broad daylight by the RAF to photograph the ports. They flew into a storm of gunfire and the attention of Messerschmitts galore. Only one, badly damaged with two of its crew wounded, returned, but the photographs it had taken revealed beyond any doubt that part of the invasion fleet had taken steps to put to sea, even if the majority of craft were still tied up. Moreover, an unusual amount of equipment was to be seen at or close by the docksides. If the invasion was not due this day, said the Chiefs of Staff to Churchill that evening, it may be expected within the next 48 or 72 hours. But they held back the precautionary code-word for invasion – Cromwell – because, as yet, there was insufficient reason to plunge the entire nation into alarm.

The first round of air attacks upon Britain on the 12th may be described as an intensive repetition of the episode of the previous day, with the exclusion of any attempt to raid across the North Sea.13 Good if, at the outset, cloudy weather, gave ample opportunity for the bombers to put into practice that morning what they had intended to do the previous evening – heavily bomb Biggin Hill, Kenley, Hornchurch, and North Weald besides making lighter attacks on other airfields which had been visited in the past, with particular emphasis on Tangmere which previously had escaped serious attention. Massed raiders fanning out over Essex, Kent, Surrey and Sussex mostly found their targets – although a number were either fended off by the defenders or forced by interior navigation to bomb secondary targets. All three Sector Stations were hit, however, Kenley receiving a particularly hard knock which destroyed its Control Room and, for 18 hours, disrupted its controlling function. Hangars, too, were wrecked so that yet another impediment was placed in the way of maintaining aircraft serviceability. The greatest damage of all in the morning was done to the Sector Station of Tangmere, where Ju 87s, followed by Ju 88s and skilfully escorted by Me 109s, deluged the airfield with high-explosive bombs to bring about the destruction of nearly all the principal buildings as well as some 24 fighters on the ground. At the same time, seven Ju 87s went for Ventnor radar station again and once more put it off the air. The loss of ten dive-bombers in these raids, heart-rending though they were to the German formation concerned, were to prove well spent, for Tangmere was of little use during the next vital 48 hours, and Ventnor was deemed as likely to be out of action for the next seven days.

Other raids, spread wide so as to confuse the defenders, found lucrative targets on a number of airfields. Naval aircraft with an anti-invasion role were destroyed in their hangars at Lee-on-Solent. Frequently, while the big raids were attracting the controllers’ full attention, two or three bombers might slip through undetected, and, in the case of the two Ju 88s which approached Brize Norton in Oxfordshire with their wheels down as if to land, achieved completed surprise with devastating results. This pair raked the hangars and destroyed 35 training aircraft plus eleven Hurricanes undergoing maintenance. As this harrowing day drew to its close, the RAF grimly counted its losses at nearly 100 aircraft of all kinds (the exact figures will never be known), and was compelled to admit that the enemy was getting on top. Although many fighters were still ‘scrambling’ into the air in sufficient time to make interceptions, a disturbingly large number were failing to get aloft early enough to be guided into action. The reasons were manifold. For one thing, the early warning system was crumbling. For another, 60 per cent of the pilots lost were the most experienced, and their replacements were neither up to the standard required to shoot down the enemy nor sufficient in numbers. Dowding was being forced to fill the gaps with men he considered unready, and to use three Polish and a single Czech squadron, all of which operated under some difficulty because of language problems. Now that the threat of invasion was imminent he could no longer call on the other Commands to transfer pilots to Fighter Command, for they would be needed in their primary roles. Finally, the wastage of aircraft was twice that of production and the stock of Hurricanes and Spitfires had dwindled to only 63, with production running at about 14 a day.

Not counting losses on the ground, the ratio of losses to strength employed still ran in favour of the Germans:

|

RAF |

Luftwaffe |

Fighters |

26, 18 pilots killed or wounded |

29, 20 pilots killed or wounded |

Bombers |

8 |

31 |

To the Germans, however, losses such as these were lowering their reserve of operational aircraft to a dangerously low level. There were, in the Luftwaffe, senior commanders who viewed these figures, in particular those relating to the bombers, in trepidation. An increasingly vocal handful expressed their dissatisfaction with Intelligence estimates which misled them with tales that opposition was declining, when almost invariably they were met by 100 fighters every time they crossed the English coast. Nevertheless, there were indications that the optimists might be on the right lines. The bombers were getting through and their losses on the 12th were fewer than on the 11th. Moreover, they could be satisfied with the performance of the Me 109 fighters which were easily holding their own. Not even Kesselring, the most optimistic of the Luftwaffe commanders, could claim that he had achieved air superiority over the intended invasion area, but he felt sufficiently confident, that evening, to brief Goering along the lines that, given good weather on the 13th and, with it, another day’s intensive operations, he could fulfill his role on the 14th of delivering the airborne forces to their destination in safety while also protecting and supporting the assault by sea.

‘It will be hard,’ he said, ‘but our fighters’ serviceability is still 75 per cent and they can hold the ring.’

At Kesselring’s request, through Jeschonnek, Sperrle was asked to employ his aircraft throughout the ensuing days in pinning down the RAF in the West Country and in making sure that the ships of the Royal Navy were prevented from leaving Plymouth and Portsmouth in order to threaten the western flank of the invasion fleet. At the same time, Stumpff’s Luftflotte 5 was to mount, from Scandinavia, just enough effort to dissuade the enemy from making an unchecked diversion of forces from north Britain to the south. On both flanks, minelaying was to be maintained at maximum intensity, with particular emphasis upon the placing of mines in the known, half-mile wide channels which were daily swept by the British in order to keep the sea lanes open, and which now were crucial to allow warships to rush unhindered to any threatened point. At the same time, aircraft were instructed to make a special point of strafing minesweepers whenever the opportunity arose, one Staffel of Me 110s being given this work as its primary task. Kesselring intended to cleanse the air space between Rye and the North Foreland of enemy fighters and, on the evening of the 13th, as the invasion fleet headed for its destination and the airborne troops prepared to enter their Junkers 52s and gliders, to project an all-out aerial bombardment at key positions near Dover and Folkestone and communications centres a few miles inland.

The German weather forecast said that, towards the end of the 13th and on into the next 48 hours, the prospects were good. Indeed, throughout the night of the 12th/13th, the winds which had risen to whip up a choppy sea, would begin to die away and the right conditions for a substantial air attack on the 13th were assured. So when Hitler met his colleagues that morning the last valid reason for withholding the decision to go had evaporated. The transcript of this fateful conference merely quotes routine reports and the Führer as saying, ‘Let “Sealion” start tomorrow.’ But those who have reminisced upon that scene have left behind a fairly unanimous impression of men in agitation. There had been a long pause, after Goering, the last to give his affirmative had spoken, before Hitler said his piece.

‘Only now,’ wrote Raeder in his private diary, ‘did it seem that the enormity of what he had started dawn upon Hitler. I thought I detected a flicker of fear – or was it mistrust – in the eyes which, in previous days, had shone only with a hard and hellbent wilfulness. Just then I thought – I foolishly dreamed – he might at this last moment recognize the folly of his intentions. But it was only a dream.’

Yet even Raeder felt satisfaction that morning with the auguries as presented to him by reports of the previous night’s operations at sea. Once more a British cruiser and three destroyers had ventured out from Sheerness to bombard the invasion ports and this time the laugh had been with the Germans. The cruiser concerned, HMS Newcastle, was rounding the North Foreland and approaching her bombarding position when she struck a mine which had been laid only an hour before at dusk. Badly holed, she turned for port, retaining one destroyer as escort and sending the remaining two to complete the mission. The bombardment thus forfeited much of its weight on a night when RAF Bomber Command was putting in its maximum effort all along the Channel Coast (losing six aircraft in the process with many more damaged by furious anti-aircraft fire as they delivered their attacks from a suicidally low level in order to make sure of scoring hits). On the way home, Newcastle was torpedoed by an S boat and brought to a standstill, exposed to whatever mischief the Luftwaffe might wreak by daylight. As, indeed, it did when a special Staffel of Ju 87s made deadly practice to sink her at a time when Fighter Command had its hands full elsewhere.

On every one of the 400 airfields throughout western Europe which stood within range of Britain there was feverish activity on the morning of the 13th. Every aircraft which could fly and which had a chance of inflicting damage upon the enemy, was made ready. The final adjustments were being made, too, to the Ju 52s of the airborne force, and those selected to tow the gliders were already preparing to take off for the fields in France where the DFS 230 gliders were assembled.

The full fury of the bombers and fighters was unleashed upon Essex, Kent and Sussex as soon as it was light enough to see the targets. From dawn to dusk there were to be German fighters standing guard over the south-east corner of England while the bombers wrought havoc upon the airfields below. Hornchurch, Manston, Hawkinge, Lympne, West Mailing and Detling each received their initial dowsings with bombs and from then on were prey to smaller, follow-up raids which remorselessly reduced them to impotence. Radar stations, too, were attacked between Newcastle and the Thames by a few low flyers, thus lending credibility to those in British Intelligence who still clung to the concept of the main invasion falling upon East Anglia. The RAF fighter squadrons were driven back to defend their inner ring of airfields. Although the Observer Corps continued to give accurate warning of raids once they had crossed the coast, they could not eliminate surprise. Regularly the Germans broke through to be met by fighters deeper inland at the point when they were approaching the limits of their radius of action, putting them at a disadvantage. But the simple fact that the Spitfires and Hurricanes were compelled to adopt a rearward position meant that the Luftwaffe had achieved freedom of action over the coastal belt which now lay at the mercy of unescorted bombers. Life for soldiers and civilians in these exposed districts became distraught as German aircraft returning from inland missions made a practice of machine-gunning traffic on the roads. The slightest movement seemed to attract their attention. People who had the mind to evacuate in the daytime either gave up the idea or took to the roads by night.

Towards evening, when the Cabinet and the Chiefs of Staff were already in possession of sufficient information to convince them that the invasion would probably come within the next 24 hours, the surviving Dunkirk radar station began to report the build-up of yet another massive formation of enemy aircraft over the Pas de Calais. The exhausted fighter squadrons again were brought to Readiness on the inland fields – some of them down to eight machines each, most of them committed to flight for the sixth or seventh time that day. This, Dowding thought, would be the culminating blow aimed at demolishing the Sector Stations, and so take-off was delayed for as long as possible. But he was wrong. Instead of probing deeply towards London, the bombers – many of them Ju 87s – split up into several groups, escorted by fighters, and plunged upon targets which, hitherto, had only received passing attention. Within the space of 40 minutes the railway system and the roads of south-west England were in chaos as bombs were rained on vital junctions – on St rood, Maidstone, Tonbridge, Lewes and Ashford, besides a number of smaller route centres – to bring about the partial isolation of the region which was soon to be a battlefield. This surprise switch of targets delayed the commital of RAF fighters to action, thus allowing many enemy bombers to return home before they could be caught. Running fights broke out all the way to the sea and the Messerschmitts, waiting above, had the best of their adversaries who had descended to lower altitudes in order to tackle the bombers. No less than 18 RAF fighters were lost in this one battle in a day when the casualties suffered by both sides were heartrending – justifying as they did, though, the light-hearted comment of Hermann Goering when, on 5 June, he had envisaged the price which might have to be paid by both air forces in order to make the invasion possible.

|

RAF |

Luftwaffe |

Fighters |

65, including 25 on the ground and 32 pilots killed or wounded |

31, 26 pilots killed, wounded or missing |

Bombers |

34, including 16 on the ground |

30 |

After dark, when the bombers from both sides took off upon their routine tasks and as the Kent and Sussex countryside flickered with the fires started by day, the invasion fleet drew closer from ports which glittered by the light of flares, guns and bombs. At this time, too, the German long-range guns began a steady pummelling of Kent, one which was to last throughout a tortured night. By comparison with the cacophany and glare on either side of the Channel, the scenes of orderly intent on the airfields of Germany, where the paratroops filed to their machines, were of an exciting tranquillity made vivid by the beat of hearts stimulated by the thrill of participation in this historic and uplifting moment.

Cromwell alert

It was air photographs and the immediate battle taking place within their sight which convinced the British Chiefs of Staff that the invasion was imminent. Information gleaned from intercepts of Luftwaffe traffic (which was profuse and easier to break) spoke volumes about air raids, but divulged nothing positive about the place and date of the actual landings. The Kriegsmarine’s Enigma had yet to be understood by the cryptanalysts and the Army maintained excellent radio security by strict discipline. In London, where there was commendable calm by comparison with the clash of battle and the reigning disturbance spreading across the south-eastern lands, the Chiefs of Staff met at 1720 hours and agreed that full precautionary measures should be taken. The Navy would put to sea with all its available ships that night. The RAF would earmark 24 medium bombers for close co-operation with Home Forces and the rest of its bomber force for employment on special tasks. The Army would come to a state of eight hours’ notice and the Eastern and Southern Commands would prepare for what was called ‘immediate action’. The civil departments, on the other hand, received no warning. At 2007 hours, a staff officer at GHQ Home Forces authorized the issue of the code-word ‘Cromwell’ to Eastern and Southern Commands before the outcome of the Chiefs of Staff meeting was known. This sent the troops to their battle stations and placed essential telegraph facilities in the hands of the Army—those, that is, that were still intact after the bombing.

In the excitement of the moment, as the soldiers vacated their billets to occupy pre-arranged defensive positions, it was not surprising that some confusion prevailed and that this was heightened by the least disciplined of the land forces. Upon hearing ‘Cromwell’ (a precautionary code-word and not intended to mobilize the Local Defence Volunteers permanently) some LDV commanders not only went to their posts, but also ordered the ringing of the church bells, to signal that troops had landed.14 As a result, the remaining hours of the 13th were spent in an atmosphere of false expectancy which gradually wore off as the night passed and nothing unusual happened. The sound of aircraft seemed no louder than of late, and the guns fired to the same rhythm. By 0200 hours on the 14th, the sense of alertness had passed its zenith and, relaxing their watchfulness, men tended to doze. Except, of course, at the coast, where the noise of battle raged loudest of all.

The troops on the cliffs of Dover remained strictly at the alert. The unprecedented shelling alone ensured that. Preoccupied though they were by the spectacle across the water, their senses also, but slowly, became aware in pauses between the shelling, of engine noise different from that of the bombers. From the other side, shrouded in darkness after the moon had set at 0046 hours, could be faintly heard a strange and swelling throbbing. So intent were the watchers, that few if any heard the faint sigh of wings drifting ominously overhead as, in the glimmer of dawn, the first gliders made their landfall.

Basic air-raid precautions as advised by the British Government. (Lionel Leventhal Collection)